The circular economy paradigm demands immediate and significant adjustments and changes in management and production business processes to maintain adequate to good ecosystem conditions for the use and development of human life. In this context, we analysed the impact of female leadership in the business environment and its relationship with the conservation of planetary health. This empowers women in the transition toward circular business model within the planet's capacity.

For a panel data sample of the world's largest companies, we find that active female participation in high business positions leads to significant changes toward a model that protects the natural and endemic wealth of different ecosystems around de world. Additionally, we found that the active presence of women in the decision-making process concerning the protection of the environment, human development, and economic prosperity is strongly associated with the prospective knowledge that female independent directors possess, and to a greater extent, with the knowledge spillover that the presence of female executive directors entails.

Climate change is not only a serious threat to the planet and people, but it is also a serious threat to the global economy, affecting stability. Among other magnitudes, the World Bank (2023) claims that if changes do not occur, one of the consequences of climate change is that one hundred million people will fall into poverty by 2030. In this way, Persson et al., (2022), Richardson et al. (2023), Steffen et al. (2015) and Rockström et al. (2009) indicate that the biophysical constraints of the Earth system must be understood as the "field of action" of business activities to achieve real planetary sustainability. Thus, we would avoid a rebound effect that, from an environmental perspective, would entail ignoring the true capacity of ecosystems to provide essential services to humanity (Desing et al., 2020).

More concretely, the increase in natural disasters, frequent and abrupt temperature changes, water stress, and the growing threat of extinction of animal and plant species are some of the consequences of a linear model involving extraction, transformation, consumption, and the final and direct disposal of waste in landfills without any form of use or revaluation (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2024; Sundar et al., 2023). In this sense, the paradigm of the circular economy (CE, hereinafter) provides an effective path where the prosperous development of business activities is closely linked to the preservation, care, and recovery of ecosystems and their endemic wealth (Kirchherr et al., 2023a). Therefore, a CE business model must ensure: (i) the reduction and elimination of industrial pollutants in air, water bodies, and productive land and (ii) the reduction of the consumption of virgin materials or resources through increased recycling, leading to a corresponding rise in available resources (Desing et al., 2020; Enciso-Alfaro & García-Sánchez, 2024), establishing measures that facilitate the prosperity of communities while moving natural resources from a state of essential care to one of total restoration (Sehrsweeney & Fischer, 2022; Wagner, 2023).

However, despite the necessary transition to a CE, we currently ignore the role business leaders, such as directors, are playing due to the scarcity of business literature. The board of directors is the corporate body in charge of approving the business strategy and advising and monitoring the management team in its implementation (Hill & Jones, 1992), functions that include everything related to the environmental strategy (Prado-Lorenzo & García-Sánchez, 2010).

In this sense, several academics suggest that the presence of female directors promotes environmental benefits derived from establishing isolated activities or strategies, such as innovation-oriented projects to mitigate climate change, properly managing waste, promoting the use of renewable energy, or decontaminating aquatic ecosystems (Atif et al., 2021; García-Sánchez, et al., 2023a; Gull et al., 2023a; Issa & Zaid, 2023; Oyewo et al., 2024), among others.

The arguments behind the inclusion of women are associated with the benefits of cognitive diversity in solving problems, identifying opportunities, and exploiting projects (Foss et al. al., 2022). The presence of women increases the exchange of information, knowledge, and ideas (Lyngsie & Foss, 2017), which are associated with different attitudes, values, experiences (Eagly et al., 2012) higher qualifications (Singh et al., 2008), and the ability to effectively perform multiple tasks (Ruderman et al., 2002). Moreover, female directors have natural preferences for care and well-being (Uribe-Bohorquez & García-Sánchez., 2023a; Monzani et al., 2015), which leads to greater integration of social and environmental concerns worldwide (Amorelli & García-Sánchez, 2023).

However, the previous evidence is inconclusive, presenting contrasting views on whether gender diversity on the board is a key factor (i.e. Ben-Amar et al., 2017; Caby et al., 2024; Cordeiro et al., 2020; Lemma et al., 2023), as their presence has either negligible or no impact (i.e. García-Sánchez et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2019). These mixed results could be associated with the narrow focus of the research conducted, which centres on isolated environmental initiatives or projects that mitigate adverse impacts on specific natural resources such as water (Oyewo et al., 2024), instead of analysing the mitigation of harms across a set of natural resources. In this vein, no study has yet analysed the role of female directors in achieving the CE transition aligned with planetary boundaries. Moreover, some authors suggest that the role of women is more associated with soft versus hard sustainability dimensions (Campopiano et al., 2023), and, nowadays, a token role for female directors persists, reducing the benefits their presence could entail (Cucari et al., 2018; García-Sánchez et al., 2024).

As a contribution to current knowledge, this research aims to achieve the following objectives: firstly, to discuss and analyse the influence of female directors in establishing a transition towards an integrated CE that positively impacts the capacity of the Earth's system (RQ1). Secondly, to examine the typology of female board members, who have the greatest impact on circular business transition, by determining the role played by their connection to the company's management team, as well as their external professional expertise and experience (RQ2). We consider that female directors promote circularity within the companies in which they perform their functions. This role is justified by cognitive abilities associated with their knowledge, competencies and experience. In this vein, we argue that independent directors are professionals of recognised prestige, who meet the conditions ensuring their impartiality and objectivity of judgement, along with prospective knowledge guiding decisions that favour the competitive and sustainable differentiation of the company, thereby increasing its value. In the case of female executive directors, they have acquired knowledge through their roles, resulting in a knowledge spillover effect that is transferred to the companies, creating significant added value.

In addition to previous research interests, we propose a Composite Score, CET, which makes it possible to assess the impact of circularity initiatives implemented by large companies worldwide within the framework of the planetary boundaries defined by Persson et al. (2022), Richardson et al. (2023), Steffen et al. (2015) and Rockström et al. (2009). In our composite Score, we link the main CE strategies established in relevant literature (i.e. Geissdoerfer et al. 2017; Kirchherr et al, 2017; 2023a; Korhonen et al. 2018) to determine companies' contributions to maintaining planetary boundaries by linking them to Earth system processes. For example, we measure water recycling in a company, where the impact would result in a decrease in the use of natural water sources, facilitating the maintenance of the planetary boundary for freshwater use.

Using panel data comprising 61,549 observations from the period 2013 to 2022, consisting of 8,923 companies operating in 9 industries, located in 74 geographical areas, we find that the presence of women in organisational leadership positions has a positive and significant impact on the shift from a linear to a circular business paradigm, integrated with the biophysical capacity of the planet Earth. Regarding the categories of female directors and the associated knowledge effect, we observe that the presence of female executive directors exerts a greater influence on the circular transition. This is identified through a more prevalent knowledge spillover effect compared to the prospective knowledge of female independent directors. The results remain robust across various methodological specifications involving the use of different and complementary techniques and measures.

The intrinsic contributions of our work are manifold. First, following the notions presented by Richardson et al. (2023) and Desing et al. (2020), we present a practical integration of the CE paradigm into the preservation of the planetary boundaries, crucial for maintaining a balanced and safe Earth system for human subsistence, providing business guidance directly connected to environmental care. Secondly, from a more operational and procedural standpoint, our CE score complements previous literature by authors such as Geissdoerfer et al. (2017) and Kirchherr et al. (2017), Korhonen et al. (2018). In this sense, we identify and quantify, in an integrated manner, the main circular strategies that companies in different industries can undertake to promote the care and protection of ecosystems.

Thirdly, we observe that changes are taking place regarding the responsibilities that women assume within businesses. While the literature review by Campopiano et al. (2023) indicate that women were commonly responsible for the initiatives associated with the soft dimension of sustainability, our study shows that they are currently immersed in complex changes towards circular business models. However, their degree of involvement is conditional on their ability to implement the strategies approved by the board of directors. In this vein, our contribution extends to the business and gender literature, aligning with findings from Cambrea et al. (2023), García-Sánchez, et al. (2023b), Konadu et al., (2022) and Brahma et al. (2021), who highlight a prevalent impact of female executive directors over female independent directors in terms of environmental performance. Our work identifies theoretically and empirically a knowledge spillover effect derived from the introspective knowledge that female executive directors possess about companies.

This paper is organised into eight sections. Following this introduction, Section 2 presents our theoretical conception of CE and its integration with planetary boundaries. It also presents a multi-theoretical perspective of the beneficial role of women directors in decision-making processes. Section 3 explores the previous literature and our proposed hypotheses. Section 4 details the conceptual definitions of variables, their measurements, proposed empirical models, and the econometric techniques employed. Section 5 outlines the results of both basic and robust models. Section 6 provides a complementary analysis of the role of female directors. Section 7 offers a discussion of the results. Finally, Section 8 concludes with the implications and limitations of our research.

Circular economy under planetary boundaries and gender roles: The state of the artA necessary transition to circular economy modelsThe CE is a regenerative system that optimises the use of energy and materials, supported by strategies to reduce, rethink, refurbish, and recycle goods, and extend their useful life to an ecologically optimal point (Geissdoerfer et al., 2017; Korhonen et al., 2018). However, according to Enciso-Alfaro & García-Sánchez (2024) and Desing et al. (2020), this model must integrate the notion of the physical and biological capacity of planet Earth.

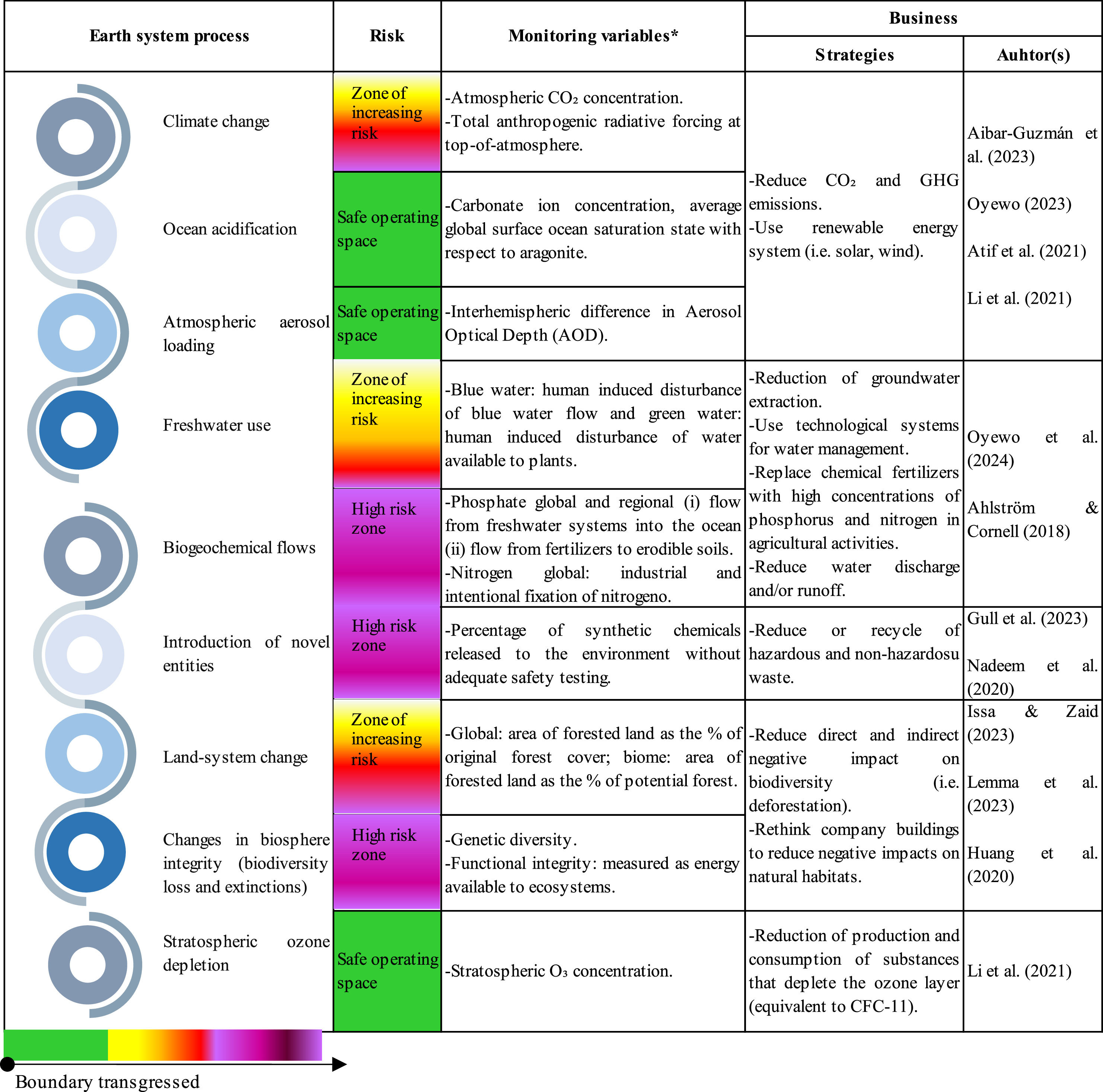

In this sense, Persson et al., (2022), Richardson et al. (2023), Steffen et al. (2015) and Rockström et al. (2009) have developed the planetary boundaries framework, which identifies nine critical processes of Earth's system that are affected by human activities. Specific levels have been established delineating thresholds that must not be exceeded to ensure that the planet retains conditions suitable for the long-term subsistence of humankind. These levels are materialised in monitoring variables for each process, providing information on the safety zone or risk of exceeding the planetary boundary (Richardson et al., 2023).

From this perspective, firms need to introduce several changes in their business models, leading to positive outcomes for brand reputation and performance (Mazzucchelli et al., 2022). This approach aligns the CE with broadly inclusive sustainable development. Firstly, it involves reducing the consumption of virgin raw materials, utilising recycled raw materials, and fostering disruptive process and product innovation. This approach aims to protect natural resources essential for maintaining the physical conditions suitable for human life, safeguarding existing endemic species, and ensuring the long-term maintenance of the Earth's systems (Geissdoerfer et al., 2017). Secondly, it ensures economic and business progress by providing a new physical and cognitive resource base that favours the optimisation of production, environmental, and reputational costs. Companies, in this context, aim to provide goods and services that meet social requirements (Bocken et al., 2016; Kirchherr et al., 2023b; 2017). Thirdly, it aims to achieve intercommunity relations and the use of infrastructures, under the notion of a planet with biophysical processes structured for human development, which must operate under material limitations that ensure their functioning (Clube & Tennant, 2023; Enciso-Alfaro & García-Sánchez, 2024).

In order to integrate the different CE proposals, Fig. 1 presents a synthesised form of the Earth system processes, the current state of the planetary boundary, their monitoring variables, and some business strategies contributing to keeping them in a safe zone. This conceptual model has been used in the empirical design of our CE transition model.

Integrating business circularity into the planetary boundaries. Source: Own elaboration based on Persson et al. (2022), Richardson et al. (2023), Steffen et al. (2015) and Rockström et al. (2009). *For more details, you might review: https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/planetary-boundaries.html

In accordance with the findings of Campopiano et al. (2023), the cognitive dimension of female leadership is constituted by the accumulation of knowledge and experience, the capability to process intricate corporate issues, and the capacity to devise efficacious corporate strategies, contingent upon the role played by direct women in the boardroom (Yukl, 1989).

In this context, Torchia et al. (2018) investigated the relationship between board gender diversity and organisational innovation in the Norwegian context. Their findings suggest that the knowledge of women directors contributes to the correction of cognitive bias within the boardroom, facilitating creativity and enriching positive debate in the selection of corporate strategies.

Similarly, Kanadlı et al. (2022) present a theoretical argument that the involvement of women in the boardroom enhances the capacity of the board to make decisions regarding environmental sustainability. This is based on the premise that women directors possess a unique cognitive framework shaped by their knowledge, skills, beliefs, and values.

Moreover, Al-Najjar & Salama (2022) have identified that the influence of women directors in the development of effective environmental practices in technology companies is strongly motivated by their knowledge and skills, which facilitate the addressing of the complexity of stakeholders' environmental demands.

In this sense, there is an important academic debate regarding the incorporation of women in upper leadership positions and its implications for decision-making processes. Several authors, such as Nguyen et al. (2020) or Terjesen et al. (2009), defend the gender heterogeneity of the board and its interrelation with environmental aspects from a multi-theoretical perspective.

In contrast with the aforementioned findings, studies conducted by Byron & Post (2016) and Campopiano et al. (2023), Kakabadse et al. (2015) indicate a lack of clarity regarding the manner in which the knowledge and typology of women directors contribute to business decision-making processes, particularly in relation to issues pertaining to environmental sustainability. This research aims to address this gap in the literature by employing a multi-theoretical framework to examine the impact of women directors' knowledge on the transition towards a circular business model.

From a social perspective, the moral norm activation theory of altruism (Schwartz, 1977) posits the existence of intrinsic norms within individuals, predicated on notions of responsibility and ethical conduct. The degree of awareness of a problem may serve as a catalyst for an altruistic response or benefit vulnerable entities, such as ecosystems.

In this vein, the theory of the ethics of care highlights the difference in the responses that men and women give to conflicts present in their environment, reflecting diverse worldviews (Gilligan, 1993). Women understand the interaction with the natural environment as a profound relationship of interdependence. They recognise that the environmental conservation is vital for human subsistence, giving rise to altruistic behaviour - protection and care of ecosystems. Simultaneously, they engage in a cognitive process where they observe the current state of nature, evaluate the consequences on social development of inadequate resource use and understand their responsibility to make decisions that mitigate harm to the environment (Gilligan, 1993; Robinson, 1997; Schwartz, 1977; Stets & Biga, 2003; Tourtelier et al., 2023). On the other hand, men perceive their connection with the environment as a non-interdependent relationship, giving priority to personal satisfaction and making it difficult to assess the negative consequences on the environment in the long term (Gilligan, 1993; Schwartz, 1977; Stets & Biga, 2003).

Furthermore, the social role theory (Eagly & Steffen, 1984) points to the existence of gender stereotypes developed from a sexual division of labour within a society with different professional implications. Women, often tasked with domestic duties and sometimes lacking vocational training, have developed a greater sense of care, protection and solidarity with their social and environmental surroundings. In contrast, men, typically responsible for providing resources to support the household, focus on acquiring professional training to improve their skills and occupy higher-paying jobs, orienting their thinking towards constantly increasing economic resources (Eagly & Steffen, 1986). To overcome this role gap, women have historically had to adapt and strive to match men's educational and employment achievements (Uribe-Bohórquez et al., 2023b).

From a corporate governance perspective, visible features such as female directors are associated with an ethical balance on the board's decisions concerning environmental issues in critical socio-economic and industrial contexts (Amorelli & García-Sánchez, 2023; García-Sánchez et al., 2023a; Lu & Herremans, 2019). This is reinforced by the resource dependence theory (Pffefer & Salancik, 1978), which favours an increase in the number of female independent directors to obtain benefits associated with a higher level of interaction with the external environment, reputation, and trust (Nguyen et al., 2020; Terjesen et al., 2009).

Moreover, the agency theory points to board monitoring as an effective inhibitor of opportunistic management behaviour, highlighting the importance of overseeing management and properly setting policies that respond to the demands of an environmentally critical landscape, largely determined by the independence of directors (Fayyaz et al., 2023; Glass et al., 2016; Jensen & Meckling, 1976; Liao et al., 2015; Terjesen et al., 2009). In this sense, previous literature registers the benefits of female advising and supervision in positively impacting corporate environmental performance (Atif et al., 2021; Elmagrhi et al., 2019; García-Sánchez, et al., 2023a; Gupta et al., 2023; Orazalin & Mahmood, 2021).

Finally, the upper echelons theory argues that a heterogeneous board composition is a key point in corporate decision-making, as it provides multiple and rich individual perspectives when making decisions, as a consequence of the directors' experiences, beliefs and priorities (Hambrick & Mason, 1984; Nguyen et al., 2020). In this vein, the human capital theory (Becker, 1964) argues that the accumulation of knowledge, the strengthening of cognitive capacities, and the improvement of individual skills, given by the constant interaction within areas of a company, enhance the professional development of women executive directors and enrich their capacities in resolving organisational conflicts (Johnson et al., 2013; Terjesen et al., 2009; Wiersema & Mors, 2023).

Research hypothesis: The role of women directors in circular transitionWomen directors and their environmental potential as key corporate governance actors in the implementation of the CEResearch supports the benefits of having women on corporate boards and the impetus they provide for implementing pro-environmental specific actions and reinforcing corporate commitment to sustainable development (i.e. Birindelli et al., 2019; Cordeiro et al., 2020; García-Sánchez et al., 2023b; Ginglinger & Raskopf, 2023; Monteiro et al., 2021; Uribe-Bohórquez et al., 2019). Women directors provide an integrative and reflective perspective on different possible corporate responses by assessing the long-term implications and effects on environmental issues, focusing on the interests of stakeholders (Bazel-Shoham et al., 2023; Issa, 2023; Issa & Bensalem, 2023).

Several studies provide empirical evidence of a positive relationship between board gender diversity and specific actions in the transition towards a more circular business model. In this context, climate change, the reduction of carbon dioxide emissions (CO2), the use of renewable energy systems, and the disclosure of information on these results are positively related to female corporate leadership (Al-Najjar & Salama, 2022; Ben-Amar et al., 2017; Caby et al., 2024; García-Sánchez et al. 2023a; Liao et al., 2015; Oyewo, 2023; Trinh et al., 2023).

In addition, Oyewo et al. (2024) found that board gender diversity drives water recycling as a strategy for managing the influx of plastic particles into aquatic ecosystems in both high and low pollution industrial settings. Lakhal et al. (2024), Gull et al. (2023a; 2023b), Burkhardt et al. (2020) and Nadeem et al. (2020) noted that women directors actively promote the development of innovations aimed at eliminating pollutants from products, addressing negative environmental externalities in production processes, and contributing to effective waste management. Lemma et al. (2023) provided empirical support indicating that a greater presence of female directors in the boardroom increases corporate commitment to biodiversity conservation, even in extractive industries. Additionally, Issa & Zaid (2023) indicated that these directors actively encourage the disclosure of information regarding the protection and care of endemic biodiversity.

In general, empirical evidence for concrete environmental initiatives suggests that women's active participation on the boards is beneficial for the implementation of specific CE actions. Although some research has shown a negative or non-significant relationship between board gender diversity and issues such as eco-innovation or eco-design projects (García-Sánchez et al., 2021), or the protection of natural resources due to environmental policy decisions being weak in Latin America contexts (De Abreu et al., 2023).

Thus, based on the moral norm-activation theory of altruism, the ethics of care, and social role theory, we advocate that women directors will think and behave in a deliberately more ethical and interdependent way towards the protection, restoration, and conservation of natural ecosystems than their male counterparts (Atif et al., 2021; Ben-Amar et al., 2017; García-Sánchez, et al., 2023b; Issa, 2023; Issa & Bensalem, 2023; Stets & Biga, 2003; Trinh et al., 2023). This ethical approach leads them to drive relevant actions to advance the transition towards a full CE for companies.

Likewise, based on the arguments of resource dependence, agency, upper echelons, and human capital theories, we envision that female advisors will bring strong inter-organisational knowledge, disruptive environmental ideas, and dynamic engagement with the business environment (Bazel-Shoham et al., 2023; Caby et al., 2024; Cordeiro et al., 2020; García-Sánchez, et al., 2023a; Gull, et al., 2023b; Konadu et al., 2022; Lakhal et al., 2024). This, in turn, enhances the board's capacity to make strategic decisions aligned with a transcendent environmental benefit for future generations.

In light of the above, we anticipate that board gender diversity will propel a more significant business commitment to the transition to a circular model, addressing pressing environmental demands. This expectation leads to the formulation of the following hypothesis:

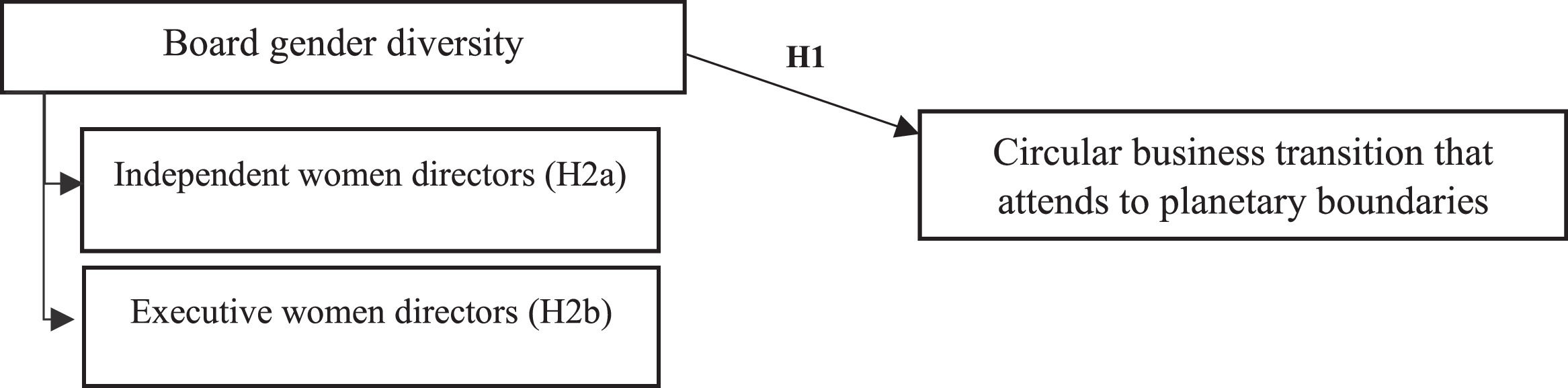

H1: The corporate circular transition that attends to planetary boundaries is driven by greater board gender diversity.

External company perspective: The prospective knowledge of female independent directorsIn line with resource dependency and agency theories, the independence of women directors provides a dynamic, expansive, and multifaceted perspective on significant global environmental, social, and economic concerns, such as climate change and social inequity generated by the inappropriate utilisation of natural resources (Atif et al., 2021; García-Sánchez et al., 2021; García-Sánchez, et al., 2023b). This constantly equips the board with "prospective" knowledge and advice that respond to major global issues (García-Sánchez, et al., 2023b). This prospective knowledge, rooted in both the past and the present, involves the use of collective intelligence in a systemic and structured manner, enabling the exploration and anticipation of future changes.

Empirical results from Lakhal et al. (2024) and Liao et al. (2019) highlight the significant influence of female independent directors in establishing eco-innovation and eco-design projects. Additionally, the literature indicates that for other individual circularity initiatives, such as those related to renewable energy consumption and waste management, it is female independent directors who actively promote their establishment (Atif et al., 2021; Gull, et al., 2023a).

Given their global vision of the business ecosystem and their ability to provide effective advice, we expect female independent directors on the boardroom to be key promoters of an effective business transition to circularity that respects planetary boundaries. We propose the following hypothesis:

H2a: The circular business transition that attends to planetary boundaries is driven by the prospective knowledge that independent women directors bring to the boardroom.

Internal company perspective: The knowledge spillover effect of female executive directorsAccording to human capital theory, the knowledge accumulated by individuals through daily interactions in the company's strategic processes is a key factor for increasing process efficiency and deriving greater benefits for the company (Becker, 1964). The deep and broad knowledge that female executive directors accumulate through their work creates a spillover effect that balances the board's decision-making process. This effect provides a detailed and critical perspective of the company's internal strengths and weaknesses, crucial for an effective transition to the CE (Knechel et al., 2012; Neumark & Simpson, 2015).

Recent empirical findings support this approach. Liu et al. (2014) found that female executive directors have a positive effect on overall corporate performance, a stronger effect compared to female independent directors, due to their continuous involvement in corporate management. In the environmental field, the findings of García-Sánchez, et al. (2023b) indicate a positive relationship between the presence of female executive directors and the level of innovation on climate change issues, resulting from their direct management involvement. This behaviour positively impacts economic, social and governance (ESG) performance, as well as greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reductions (Brahma et al., 2021; Cambrea et al., 2023; Konadu et al., 2022).

Based on the above, we propose that the presence of female executive directors on the board drives the circular transition of business model that respect planetary boundaries, given their knowledge of the company's internal management. This knowledge, complemented by their perspectives as board members, generates a knowledge spillover effect. So, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2b: The circular business transition that attends to planetary boundaries is driven by the knowledge spillover that female executive directors bring to the boardroom.

Fig. 2 summarizes our research hypotheses and sub-hypotheses:

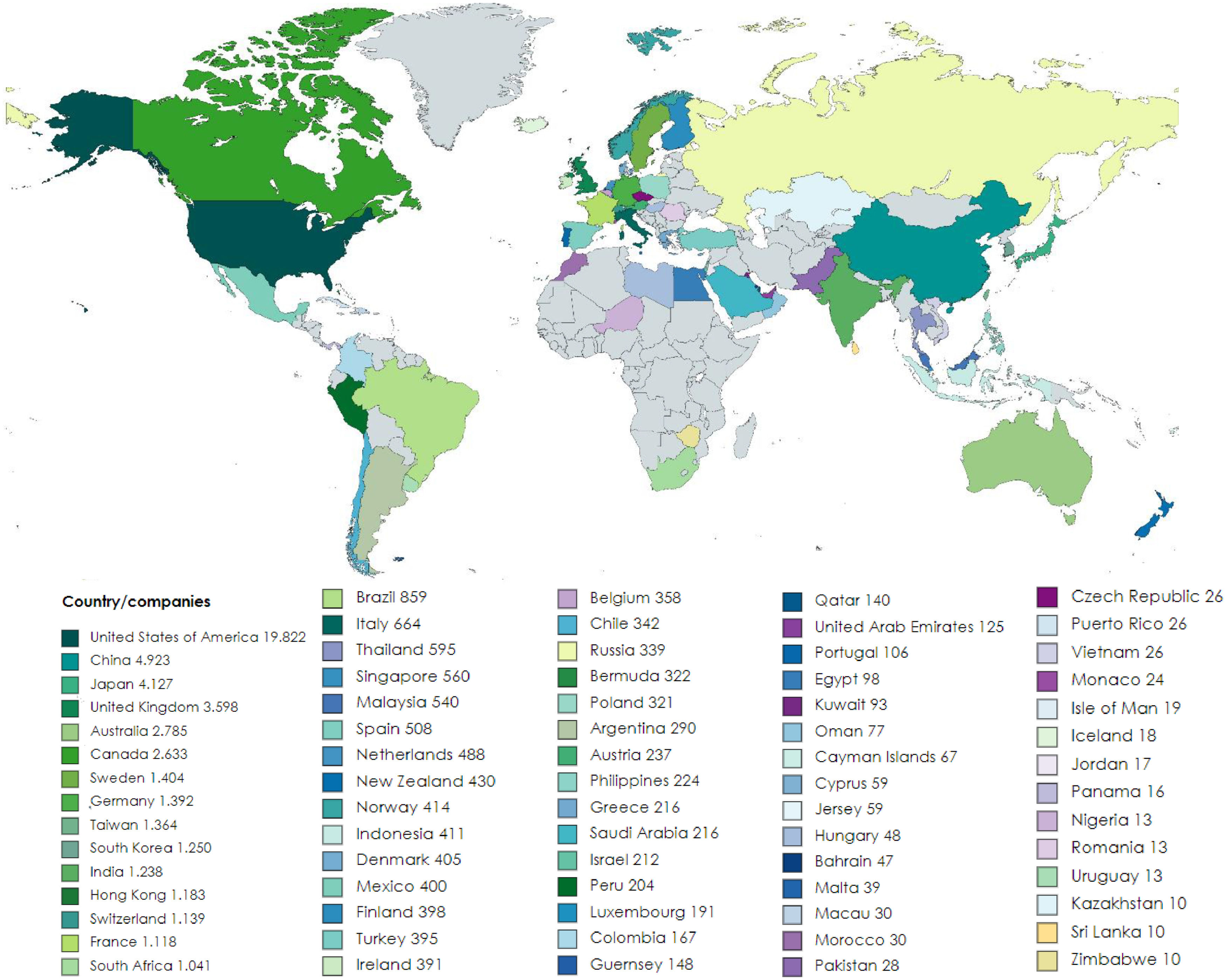

MethodSample and empirical modelsFollowing authors such as Aibar-Guzmán et al. (2023) and García-Sánchez, et al. (2023a), we have selected an international population of companies with a presence in various countries. These companies exhibit high levels of resources and capabilities, favouring the expanding development of exploitation, processing, and marketing activities. These factors lead to a greater impact on the environment and increased visibility to regulators, investors, and environmental organisations, thereby driving the business transition.

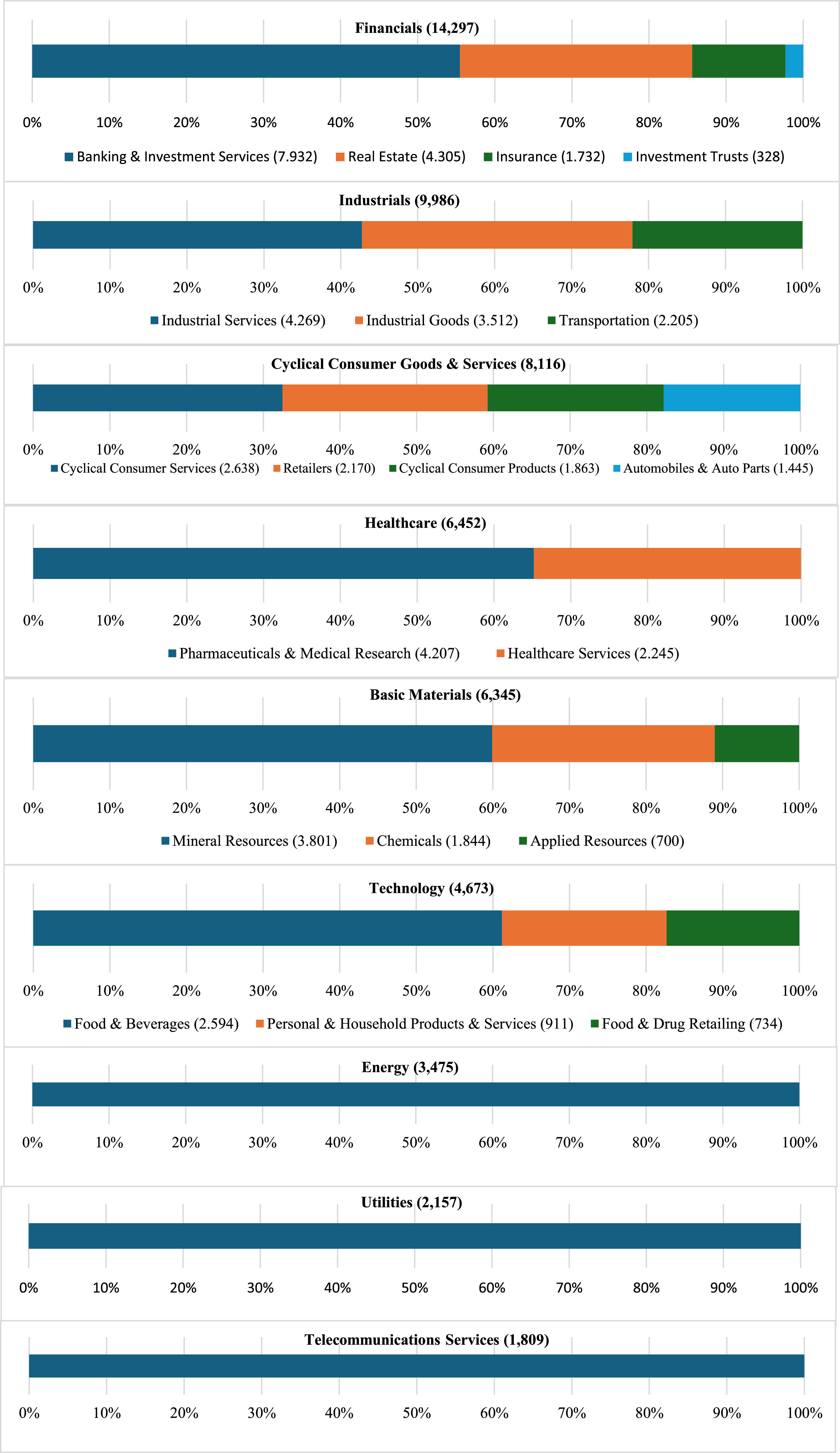

Our first criterion is the availability of economic, financial, and sustainability (ESG) information in the Refinitiv database. The initial dataset comprised 11,853 companies from 2011 to 2022. However, 2,930 companies were excluded due to the lack of consistent information, which would otherwise have enabled the identification of their progress towards a CE model. Consequently, our final research sample comprises 8,923 companies spanning the years 2013 to 2022, forming an unbalanced panel of 61,549 observations. These companies are present in 74 geographical areas (see Annex 1), providing a solid basis for testing our hypotheses. Additionally, the analysed companies are part of 9 industries: financials (14,297), industrials (9,986), cyclical consumer goods and services (8,116), healthcare (6,452), basic materials (6,345), technology (4,673), energy (3,475), utilities (2,157), and telecommunications services (1,809), see Annex 2.

To test the proposed research hypotheses, we have designed two empirical models. Eq. (1) is the basic model with which we analyse female representation on the boardroom and test hypothesis H1. Eq. (2) is the basic model that introduces the concept of the typology of female directors to analyse hypotheses H2a and H2b. Both models will be estimated with Tobit regression given the censored nature of the dependent variable to be defined later. In all models, we include ε as the error term and η as the term to control for unobservable heterogeneity. We include a lag in the independent and control variables to correct for causality. Additionally, we use centred variables to correct for possible multicollinearity problems between the individual variables (Enciso-Alfaro & García-Sánchez, 2024; García-Sánchez, et al., 2023b). To guarantee the robustness of our evidence, we will also use linear regressions with random effects for panel data as an alternative methodological specification.

In order to obtain robust results in terms of female presence and circular transition, we propose the models in Eq.s (3) and (4). These entail changes in the dependent and independent variables. Changes will also be introduced in the methodological specification proposed for their estimation, using linear regressions.

Score CET: Proposal for measuring the impact of circular transitionFollowing authors such as García-Sánchez et al. (2023a) and Tsalis et al. (2020), we propose a global score that enables the assessment of the impact of business circularity initiatives addressing planetary boundaries. This score is based on various approaches and proposals documented in research by Aibar-Guzmán et al. (2023), Atif et al. (2021), Caby et al. (2024), Gull et al. (2023a), Huang et al. (2020), Issa & Zaid (2023), Jiang et al. (2018) and Ahlström & Cornell (2018), Lakhal et al. (2024), Lemma et al. (2023), Li et al. (2021), Nadeem et al. (2020), Oyewo (2023), Salminen et al. (2022), Trinh et al. (2023). In line with these authors, we have utilised the environmental information available in Refinitiv for this purpose.

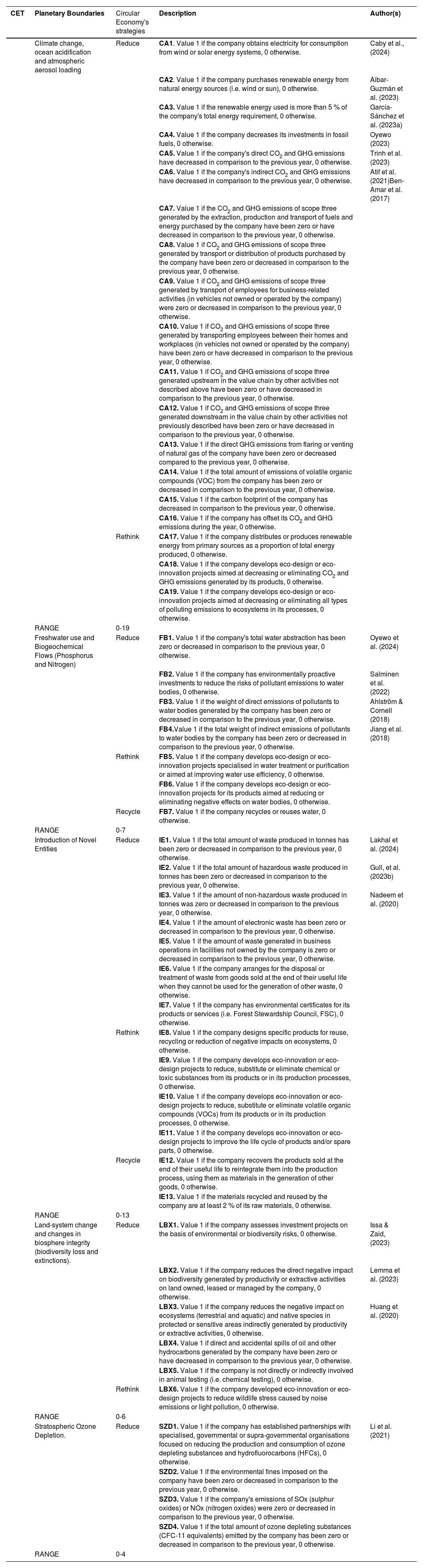

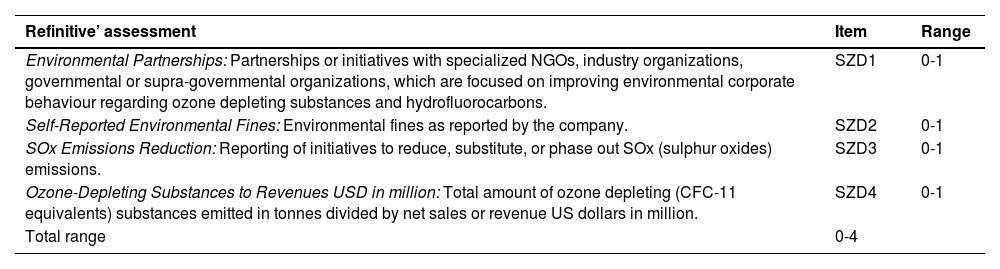

A protocol was established for the identification and coding of items, allowing the authors to independently consider and code the items. Annex 3 provides a more detailed account of the item design in accordance with the variables set forth by Refinitiv. The differences in approach were then consolidated to reach an agreement and obtain variables that quantify business actions and impacts on the environment with respect to circular initiatives. The items are associated with direct and indirect CO2 emissions, consumption of water resources, impacts on biodiversity, eco-innovation and eco-design processes, and waste management. All the initiatives and effects considered are linked to the main CE strategies -reduce, rethink, recycle-, as well as to the planetary boundaries. Table 1 shows the criteria used in the composition of the Score CET, which takes values between 0 and 49 points according to the CE items considered. Additionally, we propose ProportionCETas a robust measure, which represents the proportion of the score obtained in the transition of CE concerning the maximum possible value.

Refinitiv variables for determining items: an example for stratospheric ozone depletion.

Criteria and measures in the creation of ScoreCET.

| CET | Planetary Boundaries | Circular Economy's strategies | Description | Author(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate change, ocean acidification and atmospheric aerosol loading | Reduce | CA1. Value 1 if the company obtains electricity for consumption from wind or solar energy systems, 0 otherwise. | Caby et al., (2024) | |

| CA2. Value 1 if the company purchases renewable energy from natural energy sources (i.e. wind or sun), 0 otherwise. | Aibar-Guzmán et al. (2023) | |||

| CA3. Value 1 if the renewable energy used is more than 5 % of the company's total energy requirement, 0 otherwise. | García-Sánchez et al. (2023a) | |||

| CA4. Value 1 if the company decreases its investments in fossil fuels, 0 otherwise. | Oyewo (2023) | |||

| CA5. Value 1 if the company's direct CO2 and GHG emissions have decreased in comparison to the previous year, 0 otherwise. | Trinh et al. (2023) | |||

| CA6. Value 1 if the company's indirect CO2 and GHG emissions have decreased in comparison to the previous year, 0 otherwise. | Atif et al. (2021)Ben-Amar et al. (2017) | |||

| CA7. Value 1 if the CO2 and GHG emissions of scope three generated by the extraction, production and transport of fuels and energy purchased by the company have been zero or have decreased in comparison to the previous year, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| CA8. Value 1 if CO2 and GHG emissions of scope three generated by transport or distribution of products purchased by the company have been zero or decreased in comparison to the previous year, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| CA9. Value 1 if CO2 and GHG emissions of scope three generated by transport of employees for business-related activities (in vehicles not owned or operated by the company) were zero or decreased in comparison to the previous year, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| CA10. Value 1 if CO2 and GHG emissions of scope three generated by transporting employees between their homes and workplaces (in vehicles not owned or operated by the company) have been zero or have decreased in comparison to the previous year, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| CA11. Value 1 if CO2 and GHG emissions of scope three generated upstream in the value chain by other activities not described above have been zero or have decreased in comparison to the previous year, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| CA12. Value 1 if CO2 and GHG emissions of scope three generated downstream in the value chain by other activities not previously described have been zero or have decreased in comparison to the previous year, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| CA13. Value 1 if the direct GHG emissions from flaring or venting of natural gas of the company have been zero or decreased compared to the previous year, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| CA14. Value 1 if the total amount of emissions of volatile organic compounds (VOC) from the company has been zero or decreased in comparison to the previous year, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| CA15. Value 1 if the carbon footprint of the company has decreased in comparison to the previous year, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| CA16. Value 1 if the company has offset its CO2 and GHG emissions during the year, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| Rethink | CA17. Value 1 if the company distributes or produces renewable energy from primary sources as a proportion of total energy produced, 0 otherwise. | |||

| CA18. Value 1 if the company develops eco-design or eco-innovation projects aimed at decreasing or eliminating CO2 and GHG emissions generated by its products, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| CA19. Value 1 if the company develops eco-design or eco-innovation projects aimed at decreasing or eliminating all types of polluting emissions to ecosystems in its processes, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| RANGE | 0-19 | |||

| Freshwater use and Biogeochemical Flows (Phosphorus and Nitrogen) | Reduce | FB1. Value 1 if the company's total water abstraction has been zero or decreased in comparison to the previous year, 0 otherwise. | Oyewo et al. (2024) | |

| FB2. Value 1 if the company has environmentally proactive investments to reduce the risks of pollutant emissions to water bodies, 0 otherwise. | Salminen et al. (2022) | |||

| FB3. Value 1 if the weight of direct emissions of pollutants to water bodies generated by the company has been zero or decreased in comparison to the previous year, 0 otherwise. | Ahlström & Cornell (2018) | |||

| FB4.Value 1 if the total weight of indirect emissions of pollutants to water bodies by the company has been zero or decreased in comparison to the previous year, 0 otherwise. | Jiang et al. (2018) | |||

| Rethink | FB5. Value 1 if the company develops eco-design or eco-innovation projects specialised in water treatment or purification or aimed at improving water use efficiency, 0 otherwise. | |||

| FB6. Value 1 if the company develops eco-design or eco-innovation projects for its products aimed at reducing or eliminating negative effects on water bodies, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| Recycle | FB7. Value 1 if the company recycles or reuses water, 0 otherwise. | |||

| RANGE | 0-7 | |||

| Introduction of Novel Entities | Reduce | IE1. Value 1 if the total amount of waste produced in tonnes has been zero or decreased in comparison to the previous year, 0 otherwise. | Lakhal et al. (2024) | |

| IE2. Value 1 if the total amount of hazardous waste produced in tonnes has been zero or decreased in comparison to the previous year, 0 otherwise. | Gull, et al. (2023b) | |||

| IE3. Value 1 if the amount of non-hazardous waste produced in tonnes was zero or decreased in comparison to the previous year, 0 otherwise. | Nadeem et al. (2020) | |||

| IE4. Value 1 if the amount of electronic waste has been zero or decreased in comparison to the previous year, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| IE5. Value 1 if the amount of waste generated in business operations in facilities not owned by the company is zero or decreased in comparison to the previous year, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| IE6. Value 1 if the company arranges for the disposal or treatment of waste from goods sold at the end of their useful life when they cannot be used for the generation of other waste, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| IE7. Value 1 if the company has environmental certificates for its products or services (i.e. Forest Stewardship Council, FSC), 0 otherwise. | ||||

| Rethink | IE8. Value 1 if the company designs specific products for reuse, recycling or reduction of negative impacts on ecosystems, 0 otherwise. | |||

| IE9. Value 1 if the company develops eco-innovation or eco-design projects to reduce, substitute or eliminate chemical or toxic substances from its products or in its production processes, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| IE10. Value 1 if the company develops eco-innovation or eco-design projects to reduce, substitute or eliminate volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from its products or in its production processes, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| IE11. Value 1 if the company develops eco-innovation or eco-design projects to improve the life cycle of products and/or spare parts, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| Recycle | IE12. Value 1 if the company recovers the products sold at the end of their useful life to reintegrate them into the production process, using them as materials in the generation of other goods, 0 otherwise. | |||

| IE13. Value 1 if the materials recycled and reused by the company are at least 2 % of its raw materials, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| RANGE | 0-13 | |||

| Land-system change and changes in biosphere integrity (biodiversity loss and extinctions). | Reduce | LBX1. Value 1 if the company assesses investment projects on the basis of environmental or biodiversity risks, 0 otherwise. | Issa & Zaid, (2023) | |

| LBX2. Value 1 if the company reduces the direct negative impact on biodiversity generated by productivity or extractive activities on land owned, leased or managed by the company, 0 otherwise. | Lemma et al. (2023) | |||

| LBX3. Value 1 if the company reduces the negative impact on ecosystems (terrestrial and aquatic) and native species in protected or sensitive areas indirectly generated by productivity or extractive activities, 0 otherwise. | Huang et al. (2020) | |||

| LBX4. Value 1 if direct and accidental spills of oil and other hydrocarbons generated by the company have been zero or have decreased in comparison to the previous year, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| LBX5. Value 1 if the company is not directly or indirectly involved in animal testing (i.e. chemical testing), 0 otherwise. | ||||

| Rethink | LBX6. Value 1 if the company developed eco-innovation or eco-design projects to reduce wildlife stress caused by noise emissions or light pollution, 0 otherwise. | |||

| RANGE | 0-6 | |||

| Stratospheric Ozone Depletion. | Reduce | SZD1. Value 1 if the company has established partnerships with specialised, governmental or supra-governmental organisations focused on reducing the production and consumption of ozone depleting substances and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), 0 otherwise. | Li et al. (2021) | |

| SZD2. Value 1 if the environmental fines imposed on the company have been zero or decreased in comparison to the previous year, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| SZD3. Value 1 if the company's emissions of SOx (sulphur oxides) or NOx (nitrogen oxides) were zero or decreased in comparison to the previous year, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| SZD4. Value 1 if the total amount of ozone depleting substances (CFC-11 equivalents) emitted by the company has been zero or decreased in comparison to the previous year, 0 otherwise. | ||||

| RANGE | 0-4 |

In line with previous literature, we use a two-pronged approach to analyse the presence of female members on boards. In the basic model, BoardRoDiversity is defined as the proportion of female members with respect to the total members of the board of directors (Atif et al., 2021; Caby et al., 2024). In the model designed for robustness testing, we use BlauIndexG. This corresponds to Blau's diversity index, which takes values between 0 (lack of diversity) and 0.5 (total diversity). Its value is given by: 1−∑g=12Pg2 where g = (1, 2) represents gender (man or woman), and Pg is the percentage of each gender on the board of directors (Blau, 1977).

For identifying the typology of female directors, we define PWomenI and PWomenExe. The first variable is defined as the proportion of independent women directors with respect to the total members of the board of directors (Atif et al., 2021; Gull, et al., 2023a). PWomenExe, represents the proportion of female executive directors with respect to the total members of the board of directors (García-Sánchez, et al., 2023b; Konadu et al., 2022). For the robustness check of the typology of female directors, we use the same approach as for the analysis of the joint effect of female directors. BlauIndexWInd, as 1−∑d=12Pd2, oscillates between 0 and 0.5, where d = (1, 2) is the gender of the independent directors, that is, man or woman, and Pd is the percentage of each gender in the group of independent directors. BlauIndexWExe, calculated as 1−∑e=12Pe2, oscillates between 0 and 0.5, where e = (1, 2) represents the gender of the executive directors, (man or woman), and Pe is the percentage of each gender in the group of executive directors.

Following previous empirical work, we include in our models a vector of control variables to avoid biased results, allowing us to control for characteristics related to three entrepreneurial aspects. Firstly, those related to entrepreneurial resources and capabilities which, according to Ali et al. (2023), Amorelli & García-Sánchez (2023), García-Sánchez et al., (2023c), correspond to: Dimensions, logarithm of total assets, as a measure of firm size. ROA, measure of profitability given by the proportion of net income to total assets. Leverage, measure of company debt. Liquidity, measure of the ability to continue developing business activities in the short term. RandD, value of investments in research and development in relation to sales. CAPEX, amount of acquisitions or improvements made to physical assets related to sales. PSharesIn, percentage of shares held by institutional investors. Publicity, natural logarithm of advertising investments.

Secondly, we include variables relating to the characteristics of the board, which, according to Aliani (2023), Atif et al. (2021) and Bui et al. (2020), involve the incorporation of: BoardDimension, size of the board of directors given by the number of members that comprise it. BoardMeet, number of annual meetings of the board of directors. BoardSpSk, percentage of board members who have special skills such as a strong financial background or experience in a specific industry. DualityCEO, dummy that takes the value of 1 if the CEO is also the chairman of the board, 0 otherwise. GovernanceCCR, score adapted from (Bui et al., 2020). It takes values between 0 and 4, identifying the existence of (1) a commitment to the care and efficient use of natural resources; (2) a sustainability committee of the board of directors; (3) an ESG compensation policy for executives; and (4) executive compensation associated with sustainability performance.

Thirdly, according to Ali et al. (2023), Enciso-Alfaro & García-Sánchez (2024), Yu & Wang, (2023), we include variables relating to regional characteristics: S_EPSIndex, measuring environmental policy stringency (OECD, 2022). It is based on the degree of rigor of 13 environmental policy instruments, related to climate and air pollution. It takes values between 0 (not strict) and 6 (highest degree of rigor). EU is a dummy variable that takes a value of 1 if the company has its headquarters in the European Union for the years 2013-2022, 0 otherwise. COVID is a dummy variable that identifies the emergence of COVID-19 in 2020. STIcountry is the sustainable trade index (STI) (Hinrich Foundation, 2023) which measures the ability of economies to engage effectively and sustainably in trade, based on economic, social, and environmental indicators. We have used the environmental pillar, which assesses the extent to which an economy's trade supports sustainable resources. It takes values between 0 and 100, where 0 represents an economy with less dependence on natural resources, and 100 represents an economy with greater dependence on natural resources and, therefore, a country that is more vulnerable to market fluctuations, the decrease in reserves, and the evolution of consumer preferences.

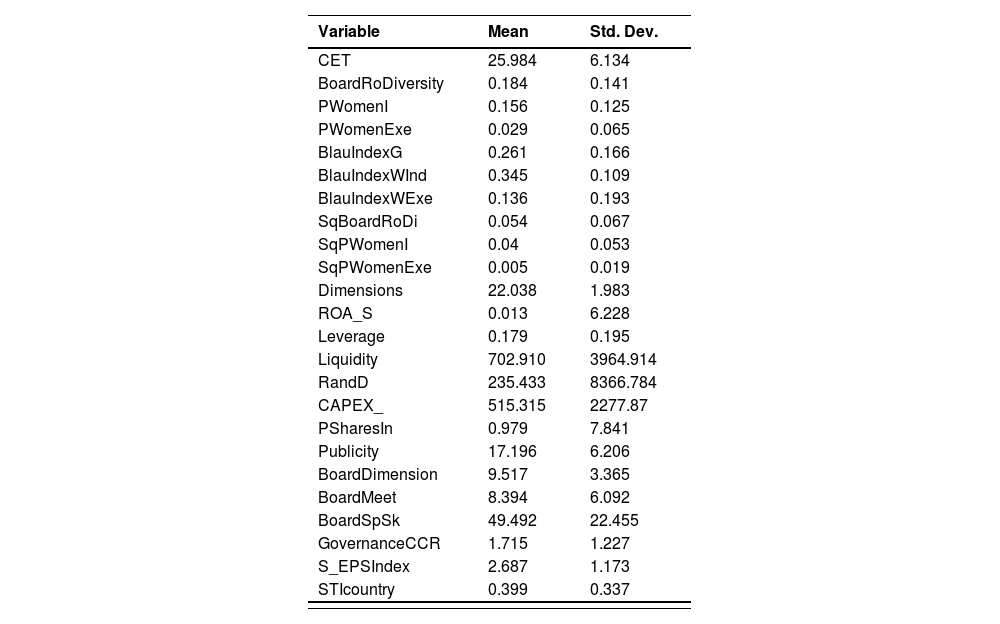

Basic and robust resultsInitial review of results: Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlationsTable 2 contains the mean values and standard deviations of the variables used for the estimation of our empirical models. The average impact of circular transition is 25.98 points out of 49 possible points, showing a 53.02 % progress in the potential effects associated with a business model that avoids land capacity saturation (± 6.134). The average female representation on the board is 18 % (BoardRoDiversity). This value is higher than the results obtained by Atif et al. (2021), Ben-Amar et al. (2017), García-Sánchez et al. (2023a), Trinh et al. (2023), but lower than those found by Caby et al. (2024), Lakhal et al. (2024) and Oyewo et al. (2024). These results indicate an increase in women's participation in corporate governance bodies in recent years; however, on average, their representation remains low. Our results show that on average 15.6 % of female directors are independent and 2.9 % are executive directors. These values are higher than those found by Cambrea et al. (2023), but lower than those found by Brahma et al. (2021). The high significance and low values of the bivariate correlation coefficients for our variables presented in Table 3 do not indicate problems of collinearity.

Descriptive statistics.

Bivariate correlations.

***p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, p < 0.1

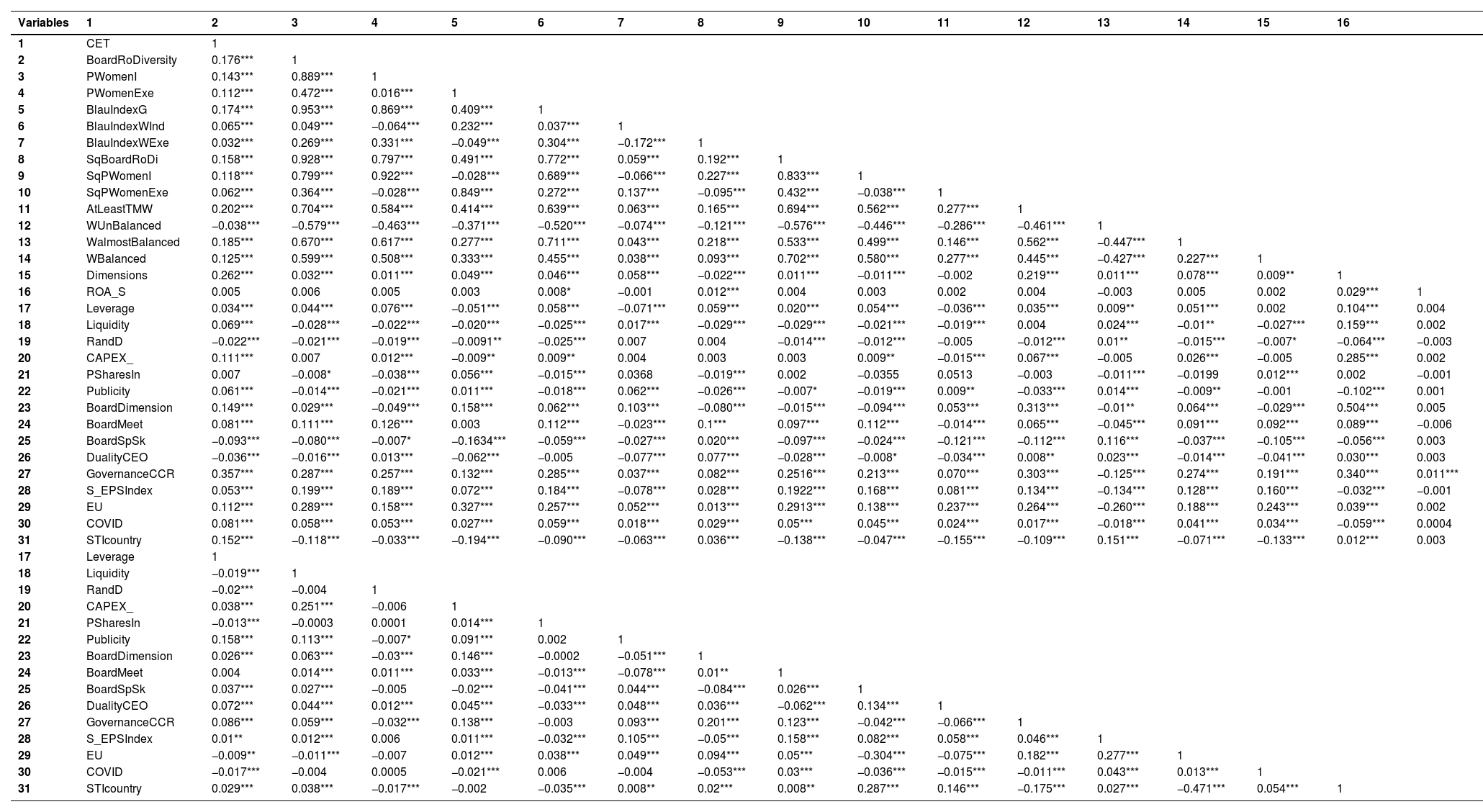

To test the hypotheses of our research, we have estimated the empirical models (1) and (2) proposed in section 4.1. The results of which are presented in Table 4. Column A shows the results relating to hypothesis H1, which examines the presence of female directors on the boardroom through the BoardRo Diversity variable. This variable has a positive and significant impact on the circular transition aligned with planetary boundaries (coeff. = 2.531; p-value < 0.01), allowing us to accept hypothesis H1. Our findings are consistent with those of García-Sánchez et al. (2023b), Issa & Bensalem (2023), Konadu et al. (2022) and Atif et al. (2021), who provide empirical evidence supporting the achievements of women's leadership in environmental care and protection.

Basic and robust results.

| Variables/columns | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | CET | Proportion CET | ||||||

| Regression | Tobit | Linear | Tobit | Linear | ||||

| Explanatory and control variables | Eq. 1 | Eq. 2 | Eq. 1 | Eq. 2 | Eq. 3 | Eq. 4 | Eq. 3 | Eq. 4 |

| Coefficient (Std.dv) | ||||||||

| BoardRoDiversity | 2.531*** | 2.446*** | ||||||

| (0.129) | (0.127) | |||||||

| PWomenI | 2.491*** | 2.389*** | ||||||

| (0.143) | (0.141) | |||||||

| PWomenExe | 2.680*** | 2.647*** | ||||||

| (0.268) | (0.267) | |||||||

| BlauIndexG | 0.0439*** | 0.0423*** | ||||||

| (0.00217) | (0.00215) | |||||||

| BlauIndexWInd | 0.00476*** | 0.00485*** | ||||||

| (0.000705) | (0.000705) | |||||||

| BlauIndexWExe | 0.00754*** | 0.00691*** | ||||||

| (0.00107) | (0.00107) | |||||||

| Dimensions | 0.750*** | 0.750*** | 0.746*** | 0.746*** | 0.0153*** | 0.0154*** | 0.0152*** | 0.0152*** |

| (0.0146) | (0.0146) | (0.0142) | (0.0142) | (0.000299) | (0.000298) | (0.000291) | (0.000290) | |

| ROA | −0.00276* | −0.00276* | −0.00274* | −0.00274* | −5.64e-05* | −5.98e-05* | −5.61e-05* | −5.91e-05* |

| (0.00151) | (0.00151) | (0.00152) | (0.00153) | (3.09e-05) | (3.10e-05) | (3.11e-05) | (3.13e-05) | |

| Leverage | −0.132 | −0.130 | −0.147 | −0.144 | −0.00294 | −0.00209 | −0.00325* | −0.00233 |

| (0.0967) | (0.0968) | (0.0958) | (0.0958) | (0.00197) | (0.00198) | (0.00196) | (0.00196) | |

| Liquidity | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| RandD | 1.18e-06 | 1.18e-06 | 1.21e-06 | 1.21e-06 | 2.59e-08 | 1.34e-08 | 2.64e-08 | 1.38e-08 |

| (3.54e-06) | (3.54e-06) | (3.41e-06) | (3.40e-06) | (7.24e-08) | (7.17e-08) | (6.96e-08) | (6.91e-08) | |

| CAPEX_ | 6.51e-11*** | 6.53e-11*** | 6.42e-11*** | 6.44e-11*** | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| PSharesIn | −0.000354 | −0.000417 | −0.000362 | −0.000448 | −1.58e-06 | −1.02e-05 | −1.99e-06 | −1.09e-05 |

| (0.00301) | (0.00301) | (0.00291) | (0.00291) | (6.15e-05) | (6.11e-05) | (5.94e-05) | (5.92e-05) | |

| Publicity | 0.0633*** | 0.0633*** | 0.0643*** | 0.0643*** | 0.00129*** | 0.00126*** | 0.00131*** | 0.00128*** |

| (0.00429) | (0.00429) | (0.00418) | (0.00418) | (8.77e-05) | (8.73e-05) | (8.53e-05) | (8.52e-05) | |

| BoardDimension | −0.000511 | −0.00105 | 0.00229 | 0.00171 | −9.82e-05 | 9.02e-06 | −3.52e-05 | 5.96e-05 |

| (0.00567) | (0.00569) | (0.00562) | (0.00564) | (0.000116) | (0.000116) | (0.000115) | (0.000115) | |

| BoardMeet | 0.00717*** | 0.00719*** | 0.00709*** | 0.00712*** | 0.000148*** | 0.000181*** | 0.000146*** | 0.000180*** |

| (0.00234) | (0.00234) | (0.00234) | (0.00234) | (4.78e-05) | (4.80e-05) | (4.78e-05) | (4.80e-05) | |

| BoardSpSk | −0.00268*** | −0.00266*** | −0.00277*** | −0.00275*** | −5.58e-05*** | −6.38e-05*** | −5.78e-05*** | −6.56e-05*** |

| (0.000708) | (0.000708) | (0.000707) | (0.000707) | (1.44e-05) | (1.45e-05) | (1.44e-05) | (1.45e-05) | |

| DualityCEO | −0.174*** | −0.173*** | −0.170*** | −0.170*** | −0.00355*** | −0.00380*** | −0.00349*** | −0.00371*** |

| (0.0381) | (0.0381) | (0.0379) | (0.0379) | (0.000779) | (0.000779) | (0.000773) | (0.000774) | |

| GovernanceCCR | 1.012*** | 1.013*** | 1.028*** | 1.029*** | 0.0207*** | 0.0219*** | 0.0210*** | 0.0222*** |

| (0.0157) | (0.0157) | (0.0153) | (0.0154) | (0.000319) | (0.000313) | (0.000312) | (0.000307) | |

| S_EPSIndex | 0.106*** | 0.106*** | 0.0922*** | 0.0922*** | 0.00222*** | 0.00330*** | 0.00192*** | 0.00298*** |

| (0.0242) | (0.0242) | (0.0233) | (0.0233) | (0.000494) | (0.000489) | (0.000475) | (0.000470) | |

| EU | 0.654*** | 0.647*** | 0.664*** | 0.655*** | 0.0140*** | 0.0177*** | 0.0142*** | 0.0178*** |

| (0.0908) | (0.0913) | (0.0881) | (0.0886) | (0.00185) | (0.00183) | (0.00179) | (0.00178) | |

| COVID | 0.509*** | 0.510*** | 0.510*** | 0.511*** | 0.0103*** | 0.0109*** | 0.0104*** | 0.0109*** |

| (0.0277) | (0.0277) | (0.0279) | (0.0279) | (0.000565) | (0.000567) | (0.000569) | (0.000571) | |

| sigma_u | 2.414*** | 2.414*** | 0.0494*** | 0.0488*** | ||||

| (0.0216) | (0.0217) | (0.000443) | (0.000440) | |||||

| sigma_e | 2.197*** | 2.197*** | 0.0448*** | 0.0451*** | ||||

| (0.00745) | (0.00745) | (0.000152) | (0.000153) | |||||

| Constant | 7.205*** | 7.202*** | 7.294*** | 7.294*** | 0.146*** | 0.139*** | 0.148*** | 0.142*** |

| (0.324) | (0.324) | (0.315) | (0.315) | (0.00661) | (0.00667) | (0.00643) | (0.00649) | |

| STIcountry | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Industry | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Year | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| R-squared | 0.4791*** | 0.4794*** | 0.4774*** | 0.4867*** | ||||

| Log likelihood | −125,026.47*** | −125,025.4*** | 79,795.56*** | 79,636.20*** | ||||

N= 61,549; standard errors in parentheses; *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

Additionally, the analysis of women directors based on their typology, presented in column B of Table 4, indicates that regardless of their professional category, their presence and knowledge complement each other. This synergy has a positive and significant impact on the establishment of pro-environmental and transitive activities towards a circular model that is highly compatible with maintaining the boundaries for the Earth's system processes. These results allow us to accept hypotheses H2a and H2b. However, the comparison of the coefficients of PWomenI (coeff. = 2.491; p-value < 0.01) and PWomenExe (coeff. = 2.680; p-value < 0.01) indicates that female executive directors have the greatest impact on an effective business circular transition, highlighting the importance of the knowledge spillover effect.

The results remain consistent when the methodological specifications are modified, with Eq.s (1) and (2) estimated using linear regression. This reinforces the robustness of our findings: BoardRoDiversity (coeff. = 2.446; p-value < 0.01), PWomenI (coeff. = 2.389; p-value < 0.01) and PWomenExe (coeff. = 2.647; p-value < 0.01).

This evidence further supports the findings of Cambrea et al. (2023), García-Sánchez, et al. (2023b), Konadu et al. (2022) and Brahma et al. (2021). They present evidence in favour of female representation on the board, particularly in executive roles, where women drive the establishment of innovations to mitigate climate change and reduce GHG emissions. This influence is attributed to their deeper understanding of the company's threats, strengths, opportunities and weaknesses.

Additionally, to enhance the robustness of our findings, we estimate Eq.s (3) and (4) proposed in section 4.3, concerning the presence of women on the board in general and by typology. The results in column E of Table 4 confirm the positive and significant impact of women directors, BlauIndexG (coeff. = 0.0439; p-value < 0.01), on the impact of business circular transition when measured in relative values. In line with these findings, the results presented in column F of Table 4 support the notion that both female independent and female executive directors play a significant role in driving the transition towards a circular business model: BlauIndexWInd (coeff. = 0.000476, p-value < 0.01) and BlauIndexWExe (coeff. = 0.00754, p-value < 0.01). Again, a greater impact is observed for female executive directors.

Furthermore, Eq.s (3) and (4) were re-estimated by modifying the methodological specification and performing a linear regression. This once again corroborates the positive and significant relationship between the presence of female directors and the corporate transition towards a more sustainable and environmentally conscious approach that aligns with the boundaries of the Earth's ecosystems. This is evidenced by BlauIndexG (coeff. = 0.0423; p-value < 0.01), driven to a greater extent by female executive directors (BlauIndexWExe coeff. = 0. 00691, p-value < 0.01) than by female independent directors (BlauIndexWInd coeff. = 0.00485, p-value < 0.01).

Regarding the control variables included in our models, which relate to entrepreneurial resources and capabilities, board characteristics, and regional characteristics, we observe that the variables Dimensions, CAPEX, BoardMeet, GovernanceCCR, S_EPSIndex, EU and COVID have a positive and significant relationship with the business transition to circularity. This transition avoids land capacity saturation and helps maintain adequate environmental conditions for the development of current and future generations. These results align with the findings of Ali et al. (2023)García-Sánchez et al. (2023a) and Atif et al. (2021), Enciso-Alfaro & García-Sánchez (2024).

Complementary analysis: Critical mass and optimal point of women directorsTo increase the richness of our results, we propose addressing the current dilemma regarding the need for a critical mass of women to avoid the token phenomenon that may be associated with their inclusion in decision-making bodies. In this context, we enrich previous evidence with an analysis of the minimum number and the optimal point of female directors required to generate positive impacts on the circular business transition that respects planetary boundaries. According to the critical mass theoretical approach (Kanter 1977), the existence of social subgroups within a larger group generates a dynamic of interaction between them, where the majority subgroup polarises and dominates the decisions of the whole. In this situation, the smaller subgroup needs to increase in size until it reaches the minimum proportion that allows it to have a "say" within the larger group and improve interactions between all members. This means reaching a critical mass of women so that their ideas are valued and influence the decision-making process in a larger group (Caby et al., 2024; García-Sánchez, et al., 2023a; Yarram & Adapa, 2021).

Empirical evidence from authors such as Atif et al. (2021) and Seebeck & Vetter (2021), García-Sánchez et al. (2023a), Gull et al. (2023a), Issa (2023), Khatri (2023), Konadu et al. (2022), Lemma et al. (2023), Naveed et al. (2023), Oyewo et al. (2024) shows that at least three women directors are required to generate a significant and positive impact on individual CE initiatives. These initiatives include reductions in pollutant emissions to ecosystems, prevention of biodiversity damage, establishment of eco-design and eco-innovation projects, responsible waste management, use of clean energy, and carbon reduction.

Thus, we propose Eq.s (5) to (8) with the objective of: (i) understanding the role of female directors linked to their representation as a subset with different sizes on the board, and (ii) determining the minimum presence they should achieve for their perspectives and ideas to be considered in board decisions regarding corporate circular transition projects.

More specifically, Eq.s (5) and (6) relate to different approaches designed to deepen the critical mass of female directors. According to García-Sánchez et al. (2023a), Gull et al. (2023a), Issa (2023) and Lemma et al. (2023), we have defined AtLeastTMW as a dummy variable that takes a value of 1 if there are at least 3 female directors on the board, 0 otherwise. Additionally, under the perspective of Kanter (1977) and following García-Sánchez et al. (2023a) and Seebeck & Vetter (2021), we have established three variables that represent three scenarios of the coexistence of gender subgroups on the board where polarisation and dominance change – men directors and women directors –. These variables are defined as follows: WUnBalanced takes a value of 1 if women directors reach a representation of at least 20 % on the board, otherwise 0. WalmostBalanced takes a value of 1 if the presence of female directors on the board is between 20 % and 40 %, otherwise 0. WBalanced takes a value of 1 if the presence of female directors on the board is between 40 % and 60 %, otherwise 0.

Furthermore, considering the emphasis on polarisation and the prevalence of Kanter's (1977) group dynamics, and in alignment with García-Sánchez et al. (2023a), we propose Eq.s (7) and (8) to offer empirical evidence on the optimal balance within the subset of female board directors concerning the business circular transition that addresses planetary boundaries. These Eq.s will allow us to determine the type of relationship (u or u-inverted) and the point of change in relation to the presence of female directors on the board and the level of entrepreneurial effort towards models aligned within planetary boundaries. To this end, we have introduced, alongside the variables BoardRoDiversity, PWomenI and PWomenExe, their squared counterparts: SqBoardRoDi, SqPWomenI and SqPWomenExe. In the case of an inverted u-shaped relationship, the coefficients for Eq. (7) are expected to be ω1>0andω2<0, and for Eq. (8) be ϑ1,ϑ2>0andϑ3,ϑ4<0. Due to the nature of the dependent variable, the Eq.s in this section are estimated using Tobit regression for panel data, and centred variables are used to control for multicollinearity of the squared variables.

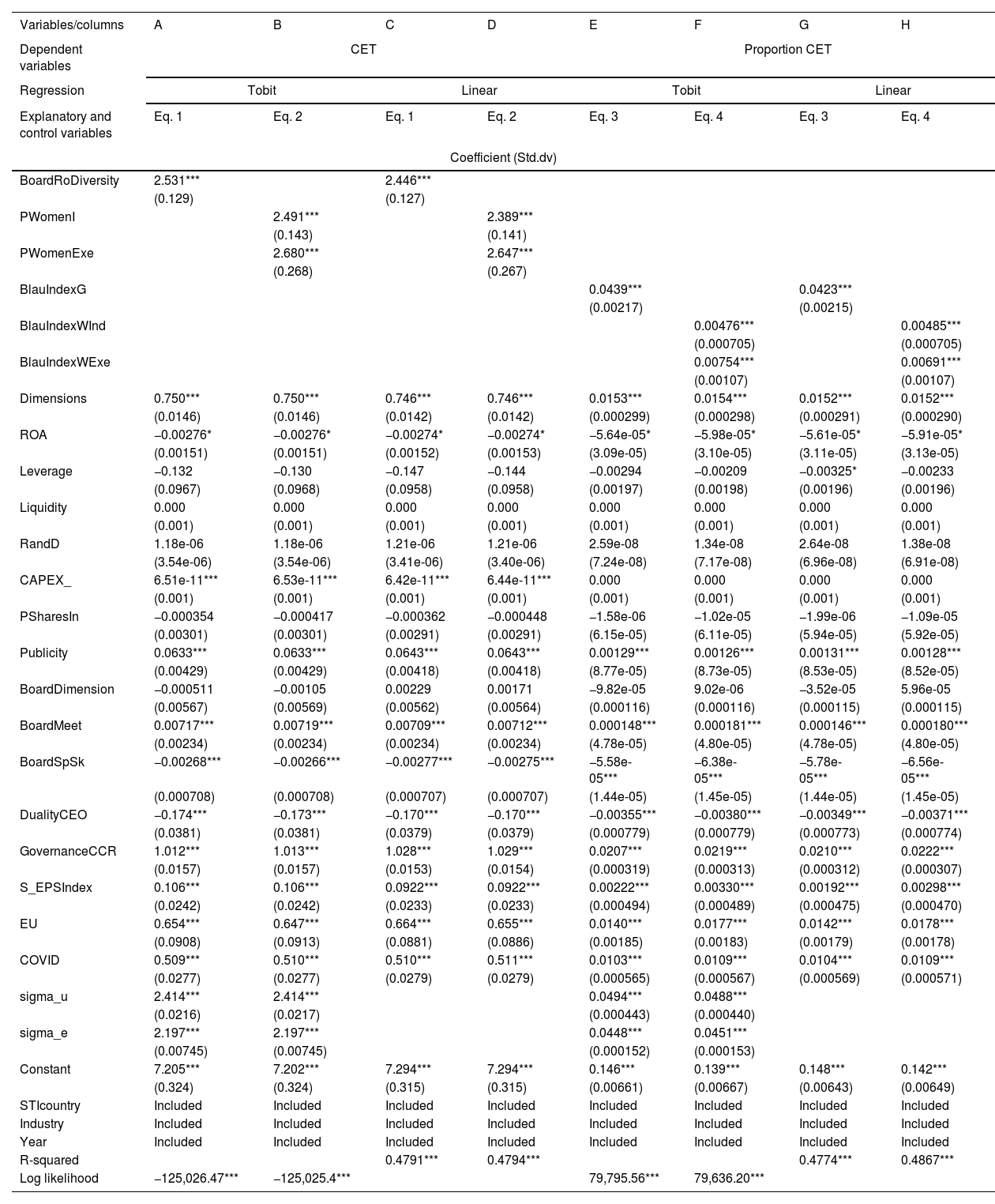

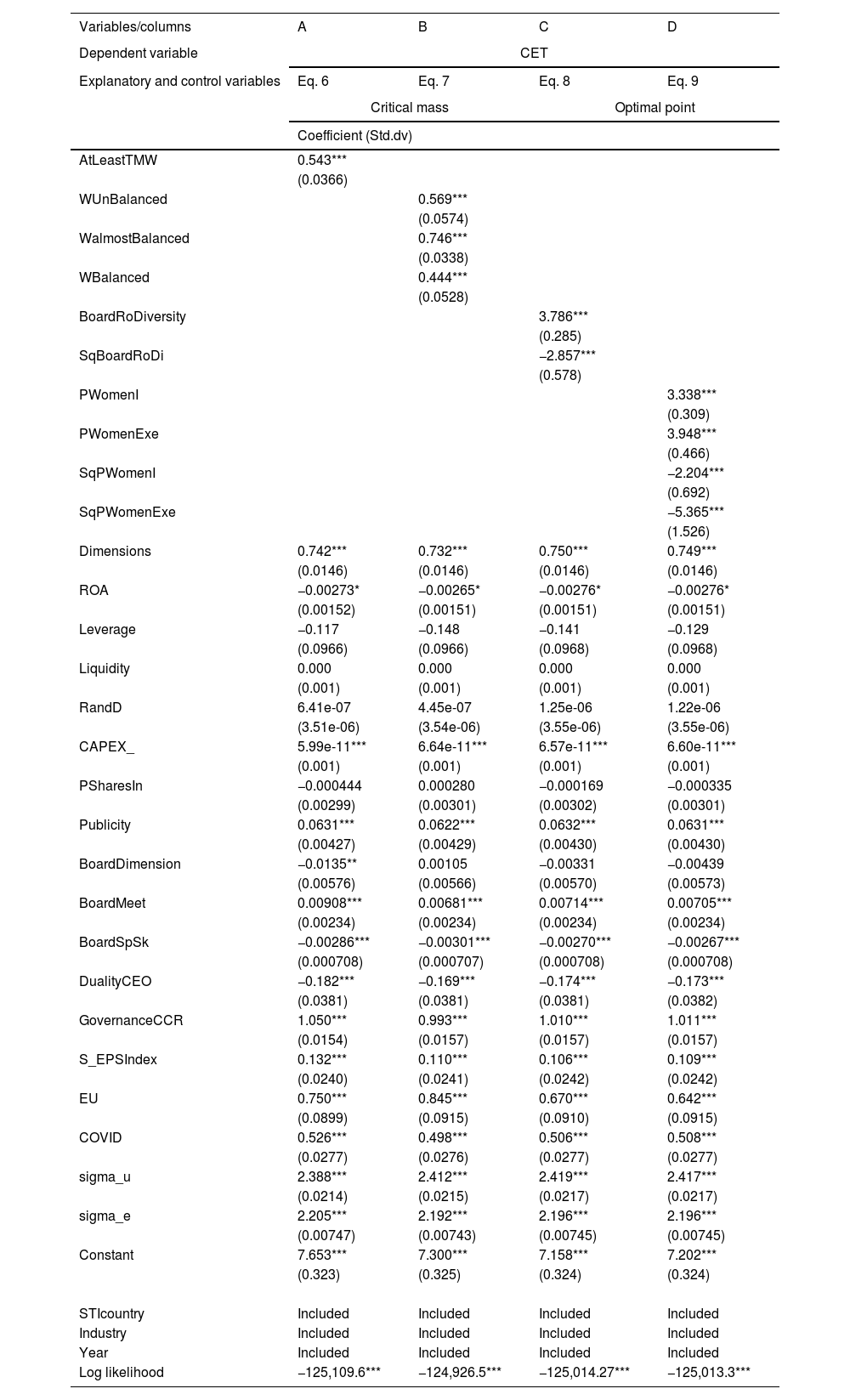

The estimation results of Eqs. (5), (6), (7) and (8) are presented in Table 5. First, the results for the critical mass in column A of Table 5 indicate that the "voice and vote" of women directors, in relation to the development of activities that ensure the effective transition to the CE, are met when they reach a minimum number of three women (δ1=0.543;p−value<0.01). These results are in line with the findings of García-Sánchez et al. (2023a), Gull et al. (2023a), Issa (2023) and Naveed et al. (2023). In addition, the results in column B of Table 5 indicate that in all polarisation and subgroup dominance scenarios, the presence of female directors is positively and significantly related to the impact of the business circular transition (λ1=0.569,p−value<0.01;λ2=0.746,p−value<0.01;λ3=0.444,p−value<0.01). However, companies in which the presence of female directors represents a proportion varying between 20 % and 40 %, constitute the critical mass for a higher level of impact of the business transition to a CE that respects planetary boundaries (λ1〈λ2〉λ3).

Complementary analysis results.

| Variables/columns | A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | CET | |||

| Explanatory and control variables | Eq. 6 | Eq. 7 | Eq. 8 | Eq. 9 |

| Critical mass | Optimal point | |||

| Coefficient (Std.dv) | ||||

| AtLeastTMW | 0.543*** | |||

| (0.0366) | ||||

| WUnBalanced | 0.569*** | |||

| (0.0574) | ||||

| WalmostBalanced | 0.746*** | |||

| (0.0338) | ||||

| WBalanced | 0.444*** | |||

| (0.0528) | ||||

| BoardRoDiversity | 3.786*** | |||

| (0.285) | ||||

| SqBoardRoDi | −2.857*** | |||

| (0.578) | ||||

| PWomenI | 3.338*** | |||

| (0.309) | ||||

| PWomenExe | 3.948*** | |||

| (0.466) | ||||

| SqPWomenI | −2.204*** | |||

| (0.692) | ||||

| SqPWomenExe | −5.365*** | |||

| (1.526) | ||||

| Dimensions | 0.742*** | 0.732*** | 0.750*** | 0.749*** |

| (0.0146) | (0.0146) | (0.0146) | (0.0146) | |

| ROA | −0.00273* | −0.00265* | −0.00276* | −0.00276* |

| (0.00152) | (0.00151) | (0.00151) | (0.00151) | |

| Leverage | −0.117 | −0.148 | −0.141 | −0.129 |

| (0.0966) | (0.0966) | (0.0968) | (0.0968) | |

| Liquidity | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| RandD | 6.41e-07 | 4.45e-07 | 1.25e-06 | 1.22e-06 |

| (3.51e-06) | (3.54e-06) | (3.55e-06) | (3.55e-06) | |

| CAPEX_ | 5.99e-11*** | 6.64e-11*** | 6.57e-11*** | 6.60e-11*** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| PSharesIn | −0.000444 | 0.000280 | −0.000169 | −0.000335 |

| (0.00299) | (0.00301) | (0.00302) | (0.00301) | |

| Publicity | 0.0631*** | 0.0622*** | 0.0632*** | 0.0631*** |

| (0.00427) | (0.00429) | (0.00430) | (0.00430) | |

| BoardDimension | −0.0135** | 0.00105 | −0.00331 | −0.00439 |

| (0.00576) | (0.00566) | (0.00570) | (0.00573) | |

| BoardMeet | 0.00908*** | 0.00681*** | 0.00714*** | 0.00705*** |

| (0.00234) | (0.00234) | (0.00234) | (0.00234) | |

| BoardSpSk | −0.00286*** | −0.00301*** | −0.00270*** | −0.00267*** |

| (0.000708) | (0.000707) | (0.000708) | (0.000708) | |

| DualityCEO | −0.182*** | −0.169*** | −0.174*** | −0.173*** |

| (0.0381) | (0.0381) | (0.0381) | (0.0382) | |

| GovernanceCCR | 1.050*** | 0.993*** | 1.010*** | 1.011*** |

| (0.0154) | (0.0157) | (0.0157) | (0.0157) | |

| S_EPSIndex | 0.132*** | 0.110*** | 0.106*** | 0.109*** |

| (0.0240) | (0.0241) | (0.0242) | (0.0242) | |

| EU | 0.750*** | 0.845*** | 0.670*** | 0.642*** |

| (0.0899) | (0.0915) | (0.0910) | (0.0915) | |

| COVID | 0.526*** | 0.498*** | 0.506*** | 0.508*** |

| (0.0277) | (0.0276) | (0.0277) | (0.0277) | |

| sigma_u | 2.388*** | 2.412*** | 2.419*** | 2.417*** |

| (0.0214) | (0.0215) | (0.0217) | (0.0217) | |

| sigma_e | 2.205*** | 2.192*** | 2.196*** | 2.196*** |

| (0.00747) | (0.00743) | (0.00745) | (0.00745) | |

| Constant | 7.653*** | 7.300*** | 7.158*** | 7.202*** |

| (0.323) | (0.325) | (0.324) | (0.324) | |

| STIcountry | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Industry | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Year | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Log likelihood | −125,109.6*** | −124,926.5*** | −125,014.27*** | −125,013.3*** |

N=61,549; standard errors in parentheses; *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

Secondly, the results presented in column C in Table 5 point to an inverted u-shaped relationship between female directors and the effective transition to a CE model that respects planetary boundaries, confirming that ω1>0andω2<0.Along these lines, we look for the inflection or optimal point where the increase in female board directors exhibits a less significant or negative relationship with the business circular transition. Following García-Sánchez et al. (2023), we calculate the optimal point as: ξ=−(ω12ω2). Thus, we found that up to 66.25 % of female directors on the board would be positively and significantly related to the implementation of CE actions within planetary boundaries. A higher proportion would decrease the effect of the female collective. Furthermore, the results in column D of Table 5 indicate the same inverted u-shaped relationship by the typology of female directors, confirming that ϑ1,ϑ2>0yϑ3,ϑ4<0.

DiscussionOur results indicate that the various actions taken by companies to safeguard and preserve the right ecosystem conditions for continuous human development are strongly driven by the vision and knowledge that women directors bring to the board. Our empirical evidence supports theoretical approaches suggesting that board gender diversity enhances the decision-making process. Women directors tend to have an introspective and deliberately protectionist approach when it comes to mitigating environmental risks and transitioning from a linear to a circular economic model that respects the Earth's biophysical capacity. This finding is consistent with the a priori literature, which documents a positive relationship between women directors and various isolated actions, such as climate change mitigation, water recycling, eco-innovation, and the conservation of endemic species. These results align with the previous empirical findings of García-Sánchez et al. (2023a), Gull, et al. (2023a), Gull, et al. (2023b), Issa & Zaid (2023)Burkhardt et al. (2020) and Nadeem et al. (2020), Lakhal et al. (2024), Oyewo et al. (2024).

Overall, our results show a complementarity of the individual perspectives brought by women independent directors and women executive directors when it comes to initiating projects or making organisational changes to achieve the ecological circularity of business operations. However, the individual effect of female executive directors on the business circular transition is greater than that of female independent directors. Thus, for the circular transition aligned within planetary boundaries, the knowledge spillover effect provided by female executive directors is more prevalent than the prospective knowledge of female independent directors.

This evidence aligns with the findings of Brahma et al. (2021) and Liu et al. (2014), Cambrea et al. (2023), García-Sánchez et al. (2023b), Konadu et al. (2022). The elucidation of this finding is supported by the theoretical perspective suggesting that directors contribute a knowledge base to organisations that expands through interaction with the companies' specific operational and managerial processes, allowing them to gain a more detailed understanding of the companies' strengths and unrealised potential.

Furthermore, our results show that the dynamics of polarisation and predominance between the gender sub-groups of the board require that the presence of women directors be between 20 % and 40 % of the total boardroom. This scenario of co-existence of sub-groups is suitable for their knowledge and participation to gain relevance compared to their male counterparts, and thereby promoting business progress towards the CE.

Additionally, our findings indicate that 66.25 % of female directors on the board is an optimal point for positively impacting the business circular transition. A higher proportion indicates a sub-group imbalance that could affect the board's decision-making process, which adds to the empirical evidence provided by García-Sánchez et al. (2023a).

Conclusions, implications and research opportunitiesThis research addresses the needs of academics and institutions to deepen understanding of optimal board configurations and contribute to achieving a CE. This CE aims to protect the Earth's system and its natural resources, while promoting community development and business prosperity. Using a novel approach to measuring business circular transition, we analyse the impact of board gender diversity on the active promotion of a CE. This approach seeks to avoid overloading the Earth's biophysical processes, in accordance with the planetary boundaries’ framework proposed by Persson et al. (2022), Richardson et al. (2023), Steffen et al. (2015) and Rockström et al. (2009). In addition, we examined and compared the knowledge prospective and knowledge spillover effects associated with different types of female directors - whether independent or executive. Our analyses also delved into the critical mass and optimal number of women directors on the board to identify how their presence can generate positive and significant impacts on business circular transition, thereby addressing issues of gender polarisation and dominance.

Our findings have several theoretical, practical and social implications. Theoretically, we establish a positive and significant relationship between board gender diversity and business circular transition. This relationship is characterised by a commitment to respecting the planet's biophysical processes, promoted by a reflective perspective and a thorough understanding of both the strengths and untapped potential of companies in favour of environmental protection, restoration and conservation.

Therefore, according to the moral norm-activation of altruism, the ethics of care, the social role, the human capital, the upper echelons, the resource dependence and the agency theories, we find that women's active participation in business leadership brings valuable perspectives and knowledge that benefit intergenerational and intercultural social groups. Our basic, robust and complementary findings support our hypotheses and prompt discussion about the optimal proportion of women on the board. This proportion can significantly impact whether a business transitions to a circular economic model or remains in a linear one, thereby enriching the empirical evidence supporting the critical mass theory.

In practical and business terms, our results have significant implications for both environmental sustainability and gender inequality in the workplace. Firstly, companies should advance towards a complete circular transformation of their operations promptly to preserve the environmental benefits they have already achieved. Additionally, companies with extensive experience and expertise in circular practices, should share their knowledge with companies in developing economies. This transfer aims solely at protecting shared natural resources. Secondly, our empirical evidence highlights the cognitive advantages that corporations can gain by increasing women's participation in leadership roles. This inclusion not only contributes to the protection of diverse ecosystems, but also promotes a more equitable environment for both men and women on our planet.

In terms of social implications, the positive impact of women's knowledge on the implementation of a CE model that seeks to protect the existing natural resource base will help ensure that individuals with unique ethnic, religious, and linguistic characteristics in developing countries have equal opportunities to access ecosystem services. We further contribute to the ongoing analysis of the gender gap in education. We demonstrate that past investments in formal and higher education for girls are now yielding significant results. The visionary dynamism of women today highlights the importance of continuing to empower girls through education in diverse fields. By doing so, we enable them to apply their talents and insights to address future challenges.

This research has important implications, but it is also essential to point out its limitations and areas for further exploration. We have identified boardroom diversity and its internal configuration as key drivers of CE implementation at the enterprise level. However, the synergy between the characteristics of other actors, such as chief executive officers or the specific attributes of investors, may also influence the business circular transition while respecting land capacity. In addition, further research is needed to explore how cultural context affects the roles and responsibilities of women in top positions.

CRediT authorship contribution statementSaudi-Yulieth Enciso-Alfaro: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Isabel-María García-Sánchez: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization.