The undeniable mutual relationship between the environment and the individual begins with the onset of human life. This human–environment relationship imposes, on every generation, the task of leaving behind a clean and sustainable environment. This study aims to investigate the determinants of pro-environmental innovative behaviours in a generational context. The study's findings provide valuable insights into the complex interplay of environmental awareness, creativity, risk-taking propensity, proactive coping and pro-environmental innovative behaviours of three generations (X, Y, Z). The results reveal substantial generational differences in the correlations between determinants such as environmental awareness, risk-taking, creativity and proactive coping. This implies that a tailored approach to encouraging innovative behaviours and environmental awareness may be required for each generation.

The relationship between humans and the environment is paramount for future generations. Therefore, humanity ought to undertake regular actions that impact the environment. In other words, the advancement of technology and a growing population require vast sources of energy for consumption, which in turn demand ecological awareness from society. That is why each study and analysis is critical for the issue of pro-environmental innovative behaviour, especially in the context of generations.

Individual behaviour towards the environment reflects one's environmental sensitivity (Gadenne et al., 2009), which can only be achieved through effective and conscious ecological education.

Researchers have argued that ecological education programmes are essential for increasing ecological knowledge, awareness and, consequently, pro-environmental attitudes and behaviours. This dependency is based on the premise that individuals with excellent environmental knowledge ought to be more aware of the environment and its problems; this then transforms into greater motivation for positive action towards the surroundings (Kollmuss et al., 2002; Otto & Kaiser, 2014).

Most research attempts on sustainable environmental development have focused their attention on pro-environmental attitudes (PEA) and pro-environmental behaviours (PEB) at home, work, and beyond. Therefore, pro-environmental attitudes are defined as a tendency to favour the natural environment (Hawcroft & Milfont, 2010), whereas pro-environmental behaviours describe all individual actions contributing to environmental protection or reducing environmental harm (Steg & Vlek, 2009). Furthermore, the relationship between the PEB and PEA dichotomy is most often explained by the theory of planned behaviour, which maintains that behaviour is determined by social norms, perceived behavioural control and personal attitudes (Ajzen, 1991).

Some studies have referred to analysing environmental problems caused by human activity and aimed at environmental protection as ‘pro-environmental behaviours’, ‘ecological behaviours’, ‘environment-friendly behaviours’ or even ‘low-emission behaviours’ (Koger & Winter, 2011). Stern (2000) divided pro-environmental behaviours into two categories: private pro-environmental behaviours (for example, purchasing, using and disposing of personal products) and public pro-environmental behaviours (discussing environmental issues, taking pro-environmental policy actions and encouraging people to such actions, among others).

Therefore, the extent to which pro-environmental initiatives can foster pro-environmental innovations and thereby motivate pro-environmental innovative behaviour may depend on the extent to which people perceive the initiative as formed from the bottom up – for instance, as initiated and influenced by (some) regular members of the group themselves (Jans, 2021).

Verma et al. (2019) determined that people who recognise their negative impact on the environment and reveal a common sense of responsibility are more likely to engage in environment-friendly behaviours.

Research has shown that all generations have common characteristics; however, their internal features may vary depending on the generation. In the professional literature, Generation Z is recognised as caring more about the environment and being environmentally friendly, as well as being willing to pay more for eco-friendly products (Casalegno et al., 2022; Ham et al., 2022).

Some studies have also indicated that age does not impact pro-environmental behaviours; rather, they have offered mixed conclusions about its impact, suggesting that the influence of demographic characteristics on pro-environmental behaviours diminishes for such behaviours become more widespread.

Numerous pro-environmental behaviours can be easily linked to multiple preferences and factors concomitantly. This means that studies focusing on a single measure of preferences and factors without considering others may inaccurately represent true dependency.

Those studies, suggest that intrinsic pro-environmental motivation is a valuable predictor of both pro-environmental behaviour and environmental policy support (Sharpe et al., 2021).

For instance, Bamberg and Möser (2007) concluded that eight basic socio-psychological variables influence pro-environmental behaviours: pro-environmental behaviour intention, awareness of the problem, internal contribution, social norms, sense of guilt, perceived behavioural control, attitude and ethical norms. The correlations between various factors influencing pro-environmental behaviours are complex. That is why understanding these factors and which of them play a more pivotal role than others in influencing pro-environmental behaviours is essential.

Other researchers, such as Bergquist and Warshaw (2019), Capstick et al. (2015), Prati et al. (2018) and Whitmarsh and Capstick (2018), among others, have examined changes in concerns, scepticism and perceptions of climate change as well as their determinants.

To our knowledge, research on the determinants of pro-environmental innovative behaviours in a generational context has not yet been undertaken. Therefore, we considered it critical to use generational differences, which would allow us to comprehend what determinants are characteristic of a given generation in the area of pro-environmental behaviour and what the relationships between them are.

Inspired by various scientific theories and research attempts in this field, we developed a research model to investigate and analyse generational differences. Based on the conducted analysis, we hope that the study's outcome will significantly contribute to the development of knowledge in this area of expertise.

The study presented in this article was part of a research project covering five European countries; this broad-based approach aimed to reflect the diversity of Europe and individual nations. We applied data from the CAWI (Computer Assisted Web Interview) survey and conducted the study in 2020 in Greece, Poland, Portugal, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Each country sent 500 respondents to participate in this research, for a total of 2503 individuals. The selection process was based on a random, stratified sample by gender, age, location and education.

This study focuses on the role of individuals – not organisations – in creating and implementing environmental innovations as social changes. It considers individual motivation to act, attitudes, knowledge and understanding of situations, the ability to transform knowledge into specific behaviours, problem-solving, creativity and communication skills. Since individual behaviour is complex and can be the outcome of many factors, a range of theories that can help explain why a person may exhibit pro-environmental innovative behaviours should be considered. Van de Ven (1986, p. 592) argued that ideas are the basis of innovation, and since individuals develop, communicate and adapt ideas, understanding what motivates and enables innovative behaviours is essential. However, as Dyer et al. (2011, p. 60) noted, ‘we know little about why one person is more innovative than another’.

The study findings provide valuable information about the complex interplay of ecological awareness, creativity, risk-taking propensity, proactive coping and pro-environmental innovative behaviours from the perspective of three generations. The results emphasise significant generational differences in the correlations between all the variables; this suggests that when it comes to encouraging ecological innovative behaviours and ecological awareness, a tailored approach may be required for each generation.

Having considered the literature review, we formulated the following research question (RQ): What are the main determinants of pro-environmental innovative behaviours in three generations (X, Y, Z)? The following research hypotheses were proposed:

H1 Significant correlations exist between environmental awareness and pro-environmental innovative behaviours across generations.

H2 Significant correlations exist between creativity and pro-environmental innovative behaviours across generations.

H3 Significant correlations exist between risk-taking propensity and pro-environmental innovative behaviours across generations.

H4 Significant correlations exist between proactive coping and pro-environmental innovative behaviours across generations.

Following this introduction, the article proceeds with a section dedicated to theoretical insights and hypotheses. Then, it presents the research methodology, including data, measurement of variables and analyses. Thereafter, it highlights the study results, summarises the findings in a discussion and provides conclusions; additionally, it presents limitations and suggestions for future research, including practical implications.

Theoretical foundations and hypothesis developmentPro-Environmental innovative behaviours (PEIB)Ajzen's theory of planned behaviour maintains that personal moral motives, such as personal values, beliefs and norms, can encourage an individual to more actively protect the environment and thereby exhibit positive pro-environmental behaviours (Fang et al., 2017, p. 2). In this theory, Ajzen (1985) argues that behaviour is driven by beliefs concerning the most likely consequences of an action/behaviour and whether they will be positive or negative for the individual, thus influencing their decision to act. However, some researchers (Frese, 2008) have suggested adopting a more contemporary view of individuals in the innovation process. Therefore, Virkkunen (2006) proposed the concept of transformational agency, where individuals become active agents challenging the status quo and taking the initiative to change it. Haapasaari et al. (2017) discovered that individual innovative efforts require transformational agency to turn ideas into successful innovations. Individual innovators are therefore those who want (motivated to act) and can be (cognitive abilities and personality traits) innovative (Anderson et al., 2004). Researchers, such as Ahuja et al. (2008) or Seibert et al. (2001) defined individual innovative outcomes as the ability to create new ideas and implement them, with personality traits, such as attitudes and cognitive abilities, influencing behaviour (including individual innovative behaviours).

Although innovations can encompass a broad spectrum of activities, literature reviews from various fields have emphasized identical attitudes and cognitive abilities identified as key antecedents to innovative behaviours. As regards antecedents to innovation, research has identified several critical individual characteristics that can drive innovation in various sectors (not just environmentally oriented), including risk-taking propensity, external environment, proactivity and spontaneous, proactive and persistent behaviour (Frese et al., 1997).

Furthermore, innovation can be viewed from a narrow or broad perspective. In a narrow sense, it refers to the extent to which innovations are introduced within an enterprise. In a broad sense, it refers to the performance achieved by generating innovative concepts and implementing the change. Defining innovation uniformly is challenging owing to its multiple senses; that is why different perceptions of innovation require different metrics for measuring them (Huang et al., 2023).

Finally, environmental innovations aim to reduce the impact of products and production processes on the natural environment through gradual or radical changes in enterprises’ structure and organization (Angelo et al., 2012; Ozusaglam, 2012). However, the latest definitions of environmental innovations have focused more on the actual outcomes of the implemented policies rather than merely the goals, which may not correspond to reality (Ozusaglalam, 2012).

Generational context of pro-environmental innovative behaviourGenerational differences have garnered considerable interest in the context of human capital (Tolbize, 2008; Twenge et al., 2010; Vanmeter et al., 2012) and in individuals’ functioning across all areas of daily life.

Prayag et al. (2022) identified intergenerational and intragenerational differences in ecological attitudes and travel behaviours among the visitors of the Canterbury region in New Zealand. They demonstrated that the so-called Generation Z individuals show greater environmental awareness and a tendency for sustainable actions, such as resource conservation and purchasing healthy local food. Similarly, Sharma et al. (2023) revealed that the representatives of Generation Z exhibit a higher level of environmental concern, pro-social attitudes, values of ecological consumption and engagement in behaviours that reduce food wastage compared to other generations.

Environmental responsibility significantly influences pro-environmental behaviours (Fang et al., 2019; Liobikiene & Poskus, 2019). Liobikiene et al. (2020) and Sarkis (2017) revealed an insignificant impact of responsibility on protective behaviours, while environmental responsibility significantly influenced behaviours. In their previous analysis, Liobikiene and Juknys (2016) had discovered that assuming responsibility significantly and positively determines pro-ecological behaviours.

Environmental responsibility is strongly linked to a sense of connection with nature and pro-environmental behaviours, as confirmed by several research attempts (e.g. Kals & Müller, 2012; Mackay & Schmitt, 2019). This relationship persists throughout life and affects children, adolescents and adults in a similar way (Collado et al., 2015; Krettenauer, 2017). Moreover, the sense of connection with nature is weaker between Generation X and Y, including their teenage children (Krettenauer, 2017; Szagun & Mesenholl, 1993).

Conversely, cross-sectional studies involving youth in the USA, Canada and Israel indicated negative correlations between age and the level of pro-ecological actions (Wray-Lake et al., 2017). Krettenauer (2017) claimed that a lower bond with nature mediated age-related differences in the pro-ecological behaviours of Canadian youth.

Furthermore, studies conducted in Australia by Chai et al. (2015) revealed a discrepancy between people's professed values regarding concern for climate change and their actual actions. As a result, age and education level had a mitigating effect on this gap, which means the older the person, the smaller the difference.

Studies conducted in Algeria, Ghana, Nigeria, Africa, Zimbabwe and Egypt demonstrated that in terms of aggregated results, one determinant of pro-environmental behaviours was the respondents’ age. In other words, they found no clear differences in pro-environmental behaviours among the respondents in terms of age.

Additionally, a research attempt by Ifegbesan and Rampedi (2018) in Nigeria found no significant statistical differences in pro-environmental behaviours based on the respondents’ age and marital status.

However, even though earlier studies indicated a positive correlation between age and pro-environmental behaviours, current research results have not been so unequivocal. Some researchers have even argued that age does not influence pro-environmental behaviours (Gray et al., 2019; Sargisson et al., 2020).

A study conducted in the Republic of South Africa (Rampedi & Ifegbesan, 2022) determined that age is an important predictive factor of pro-environmental behaviours. This may be due to the increase in environmental knowledge that individuals acquire throughout their lives (Amoah & Addoah, 2001; Otto et al., 2016).

Therefore, the data obtained in the survey of 342 employees across a range of industries show that while undertaking pro-environmental behaviour in the workplace is an important issue for respondents, on whose initiative such behaviour should be undertaken is ambiguous. Most respondents felt neither pressure nor support from the organisation to engage in such behaviour, regardless of whether or not an environmental management system was implemented in the organization (Tutko & Budzanowska-Drzewiecka, 2022).

Research on consumer behaviours, actions for sustainable development, lifestyle choices and pro-environmental behaviours has shown that Generation Z's behaviour differs from that of the previous generations (Prayag et al., 2022; Seyfi et al., 2023; Sharma et al., 2023).

Some studies have also focused on generational differences in pro-environmental behaviours (PEB) and have thus shown that younger generations, such as Generation Z, are more ecologically aware and engaged in pro-environmental actions (Song et al., 2020). Thus, we propose the following research question:

Research question (RQ): What are the main determinants of pro-environmental innovative behaviours in the context of generations?

Developing human ecological awareness aims to shape behaviours directed at environmental protection, both at the individual level and in a broader social context. Kollmuss and Agyeman (2002) analysed a range of factors that, in their opinion, can positively or negatively impact pro-environmental behaviours, such as demographic and external factors (for instance, institutional, economic, social and cultural).

A literature overview revealed that several ecological awareness studies have been conducted worldwide. Therefore, research attempts by Shamuganathan and Karpudewan (2015), Spinola (2015), Negev et al. (2010) and Garcesa and Limjuco (2014) emphasised that ecological knowledge consists of various elements, namely knowledge, attitudes, behaviours, awareness, concerns and sensitivity to one's environment, including a focus on defining, comparing and measuring the level of ecological knowledge of their respondents.

Khan et al. (2022) described a significant moderation of environmental knowledge in predicting consumer resistance to innovative green products. Moreover, the negative relationship was weaker in the case of higher levels of environmental knowledge.

Furthermore, Sontay et al. (2015), Yumusak et al. (2016) and Goldman et al. (2015) examined the relationship between each of the elements of ecological awareness, the impact of technological tools on the level of ecological awareness and the level of ecological awareness on specific variables such as ecological knowledge, verbal engagement, actual engagement, general environmental feelings, environmental issues and action skills. They found a medium-level positive correlation between ecological knowledge and attitude (affective), which means that knowledge about the environment can transform into feelings towards the environment and pro-environmental attitudes.

Finally, research by Bradley et al. (1999) on ecological knowledge and attitudes highlighted that students with a higher level of ecological knowledge exhibited greater pro-environmental attitudes. Therefore, if an individual has sufficient knowledge about the environment, they tend to have a positive attitude towards it.

Generation Z, raised in the digital world and communicating online, primarily derives their knowledge from the Internet; thus, the Internet largely shapes its consumers, behaviours, fundamental values and ecological awareness. Therefore, we propose hypothesis H1:

H1 Significant correlations exist between environmental awareness and pro-environmental innovative behaviours across generations.

Gough defined a creative personality as a collection of distinct personality traits associated with creativity (Gough, 1979). Certain personality traits, such as self-confidence, self-efficacy and broad interests, are associated with creativity (Barron & Harrington, 1981; Sternberg, 2006). As a result, creative individuals are flexible, capable of dealing with problems, eager to overcome obstacles, willing to take reasonable risks and tolerant of ambiguity (Runco, 2004).

Stevenson et al. (2014) found that creativity can be developed through training. Based on their research, they maintained that creativity training can improve causal reasoning among the young generation.

Since finding solutions to environmental problems depends on creative ideas, including environmental awareness with a focus on ecological knowledge, creativity can influence the degree of pro-environmental behaviours (Tsetse & De Groot, 2009). Trencher et al. (2007) developed the concept of co-creating sustainable development to encourage actions for sustainable development to transform society. Further, Tran and Park (2016) proposed a framework for the co-creative redesign of the product-service system.

A relationship exists between creativity and environmentally friendly innovations as well as between creativity and proactive environmental management (Chen et al., 2016). Some researchers believe that Generation Z has enormous potential for creativity and innovation (Dingli & Seychel, 2015).

Creativity is a personal characteristic associated with innovation, defined as generating novel ideas that are useful and appropriate in a given situation (Amabile, 1983). Much of the professional literature has focused on identifying personal traits, cognitive styles and other attributes associated with creative achievements (Amabile, 1983, 1996, 2000; Scott & Bruce, 1994).

People are believed to be more creative when motivated primarily by interest, pleasure, satisfaction and challenge, which forms the principle of intrinsic motivation of creativity (Amabile, 1996). This principle suggests that the environment can clearly bring some impact on creativity, particularly the presence or absence of external pressures.

The combination of creativity and awareness of it leads to innovation as well as eco-innovations. Implementing a new idea often involves taking the initiative to realize it (Amabile, 2000; Kanter, 1988; Van de Ven, 1986). That is why creative people have many ideas but sometimes lack a business-oriented mind and the initiative that would enable the necessary effort for their ideas to be heard and tested (Levitt, 2002).

Generations Z and Y, raised in the digital era, are adept at obtaining information about activities for innovative pro-environmental solutions thanks to technological solutions (Tapscott, 2010).

The research directions on environmental innovation identified in the literature are two. One research direction focuses on the individual level, analysing personal traits that enhance or inhibit creativity (Amabile, 2000; Scott & Bruce, 1994), whereas the other research path concerns the organizational level, examining organizational factors that strengthen or hinder the implementation of creativity-based innovations (Damanpour, 1991). That is why people must show initiative in realizing their ideas to transform them into valuable, innovative actions (Levitt, 2002). This also leads to individuals’ actions in the sphere of pro-environmental behaviours, mainly because an innovative culture encourages individuals to seek new ways of dealing with problems, take risks and explore their ideas (Amabile, 2000; Scott & Bruce, 1994). Thus, we propose the following hypothesis H2:

H2 Significant correlations exist between creativity and pro-environmental innovative behaviours across generations.

Measures of individual preferences may also predict pro-environmental behaviours, which often generate uncertain benefits; this suggests an association with risk. Indeed, risk-taking is positively associated with the likelihood of investing in, for example, energy-efficient technologies.

Objective risk-taking may differ from people's perceptions and attitudes towards risk (Charness et al., 2020), and pro-environmental behaviours can be objectively risky, even though they bring environmental benefits. Social (Fleiß et al., 2019), risk (Riddel, 2012) and time (Augenblick et al., 2015) preferences may also differ depending on the domain (money, effort, health, environment, etc.) to which they relate.

Generation Z is more achievement-oriented and risk-taking than older generations (Agustina & Fauzia, 2021). Conversely, Generation Y may be less inclined to take social risks than Generation Z because they are more likely to have an established lifestyle, with a job and daily routine, a close social environment and engaged relationships, including a family with children, and obligations and responsibilities both at work and at home, compared to Generation Z (Bakalova & Panchelieva, 2023).

Risk-taking is universal throughout adulthood, sometimes with minimal differences between Generation Z and Generation X and Y (Willoughby et al. 2021). Dyer and Sarin (1982) introduced the concept of a relative risk attitude, attempting to identify an element of risk-taking that provides situational stability for a specific person. They hypothesised that domain differences in the approach to apparent risk (inferred from the shape of the utility function) might be due to differences in the marginal value of outcomes in different domains (e.g. decreasing marginal value in relation to money but increasing marginal value over time). As a result, a person's relative approach to risk, that is, the curvature of the utility function after considering the marginal value, may still be stable across different domains, even if apparent risk-taking may differ.

In the literature, age is one of the main subjective determinants of the tendency to risky behaviour. Therefore, the tendency to take risks is greater in Generation Z than in other age groups (Silecka-Marek, 2023).

Keller (1985) and Weber and Milliman (1997) did not find evidence of any greater situational stability of a relative risk attitude in their studies. Alhakami and Slovic (1994) maintained that the often-observed inverse relationship between risk perception and benefits (people who perceive greater risk also expect lower benefits within a range of risky actions) results from people relying on general affective evaluations when taking risks and deriving benefits from them. Although a relatively small amount of the literature has linked affect to risk perception, starting with Johnson and Tversky (1983), most risk-taking models implicitly assume some integration (cognitive) of information about probability, outcome and benefits. The role of affect in this process and risk-taking has been largely ignored, even though many anomalies in choice behaviour (patterns of behaviour that are difficult to explain) result from the assumption that people make decisions based on the effect. That is why affective reactions colour the perception of threats and benefits (Alhakami & Slovic, 1994), which in turn influences risk-taking.

Subjective norms regarding appropriate levels of risk-taking play a substantial role in risk-taking, as suggested by Ajzen and Fishbein's theory of reasoned action (1997). Therefore, the perspective of loss (physical, financial or psychological) is an integral part of naturalistic risk-taking (Fox et al., 2015). Thus, we propose the following hypothesis H3:

H3: Significant correlations exist between risk-taking propensity and pro-environmental innovative behaviours across generations.

Proactive copingIndividuals can act as innovators and develop innovative techniques for dealing with environmental problems, such as pollution and food waste. However, governments and corporations also often act as innovators in this area, sometimes leading to what Angelo et al. (2012, p. 117) describe as ‘bilateral relations’.

Some findings reveal that individuals with a strong sense of intergenerational concern experience various emotions when it comes to climate change. These individuals take direct action to address the challenges posed by climate change (problem-focused coping), actively engage with the problem and seek solutions. By implementing values that emphasise intergenerational concern as a key priority, we can not only increase pro-environmental action but also help individuals actively and constructively cope with the changes induced by climate change (Doherty & Claton, 2011).

Numerous researchers have studied the nature of ecological awareness, which is currently considered a domain encompassing four interconnected components: knowledge, disposition, competence and pro-environmental behaviours (Stern, 2000). Therefore, ecological innovative behaviour includes not only one's individual knowledge and ecological attitude but also the ability to cope with environmental problems and problem-solving skills. That is why a person with ecological knowledge understands environmental issues, thus promoting society's pro-environmental behaviours (Teksoz et al., 2011).

Certain studies have revealed that younger generations, who report that they are proactively coping, are more likely to expose greater pro-environmental behaviours, while those who cope less (e.g. they tell themselves that the problem is exaggerated), are significantly less likely to report pro-environmental engagement (Syropoulos et al., 2024).

Understanding environmental problems is linked to various ways of dealing with these issues and then skilfully developing solutions. Ojala (2012) discovered that the youngest generation engaging in active problem-focused coping was associated with a greater negative affect; however, this association was attenuated when they also engaged in meaning-focused coping (for instance, positive reframing). Therefore, the ways in which individuals choose to cope with climate change threats have important implications for their own well-being and the environment.

Environmental knowledge is defined as general knowledge about facts, concepts and solutions to environmental problems. It also reflects the degree of understanding and concern about the relationship between humans and nature (Fryxell & Lo, 2003). More specifically, pro-environmental innovative behaviour is presented as individuals’ knowledge of environmental protection and ecological awareness with problem-solving skills and risk-taking. Furthermore, society's ecological knowledge has increased owing to serious environmental problems worldwide, such as ecological damage, environmental pollution and ecological disturbances resulting from various human activities. That is why the issue of developing programmes for coping with environmental problems becomes substantial and is associated not only with organizations but also with individuals.

Finally, according to Medzinski (2007), factors that can be considered barriers to eco-innovation include, among others, low ecological awareness and the lack of clear information, low openness of society (‘fear of change’, risk aversion, etc.), limited access to human resources and expert knowledge and short-term decision-making in the absence of problem-solving skills. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis H4:

H4: Significant correlations exist between proactive coping and pro-environmental innovative behaviours across generations.

MethodologyMethodIn this study, we used the data from a CAWI (Computer Assisted Web Interview) survey. Conducted in 2020 across five European countries (i.e. Greece, Poland, Portugal, Sweden and the UK), the survey aimed to reflect European diversity and national variations. Each country contributed 500 respondents, totalling 2503 individuals, selected through a random, stratified sample based on gender, age, location and education.

The respondents were selected from Kantar's Internet panel mainly for their demographic diversity. The survey design included a preliminary pilot study with 50 participants per country, which helped refine the questionnaire. We conducted data analysis using the SPSS software, including a correlation analysis related to five dimensions, with the significance level set at 0.01.

Prior to conducting the statistical analysis, we assessed the data for internal consistency, cleaned and recoded. We conducted a reliability analysis using Cronbach's alpha and Guttman's lambda for each group of items related to a latent construct.

This comprehensive approach aimed to provide high-quality empirical material and insights into pro-environmental innovative behaviour (PEIB) across different European contexts.

Furthermore, we utilized four distinct measurement scales to evaluate various dimensions, namely environmental awareness, creativity, proactive coping and risk-taking propensity. The Environmental Awareness Scale by Morgil et al. (2004) comprises 20 statements that delve into perceptions around recycling, energy consumption and pollution. The participants responded using a 5-point Likert scale to express their level of agreement. The Kaufman Domains of Creativity Scale (K-DOCS) is a self-assessment, behaviour-oriented scale assessing everyday creativity across five domains: self/everyday, scholarly, performance, mechanical/scientific and artistic (Kaufman, 2012). It employs 11 statements rated on a 4-point Likert scale. The General Self-Efficacy Scale by Schwarzer and Jerusalem (1995) consists of 14 statements; the participants rated their agreement on a 4-point Likert scale, reflecting their belief in their self-efficacy. The General Risk Propensity Scale developed by Zhang et al. (2018) is a concise self-report instrument to measure general risk-taking tendencies; it includes eight items, each rated on a 5-point Likert scale.

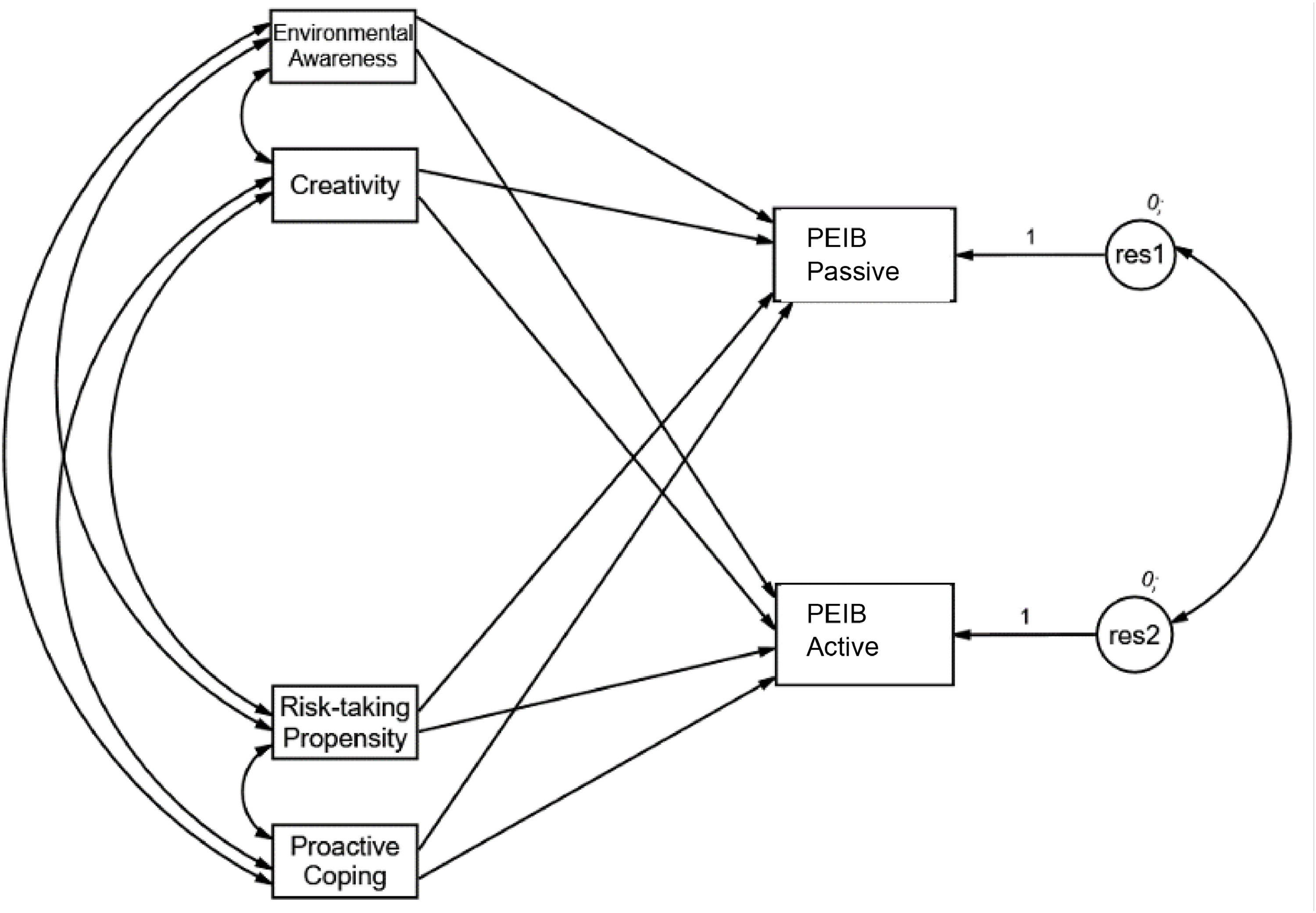

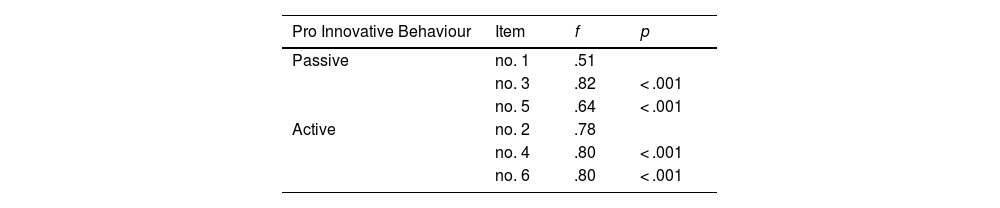

We validated the measurement of passive and active pro-environmental innovative behaviour (PEIB) using confirmatory factor analysis, and the values of fit indices revealed that the correlation was highly satisfactory. Therefore, the values were CFI = 0.99, NFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99 and SRMR = 0.04. However, an additional correlation between two items measuring PEIB passive, namely I think that a new solution to the problem should be introduced and I utilize existing solutions in my life, needed to be considered to achieve this fit, r = 0.27, p < .001. Table 1 resembles the values of factor loadings for pro-environmental innovative behaviour items acquired during confirmatory factor analysis.

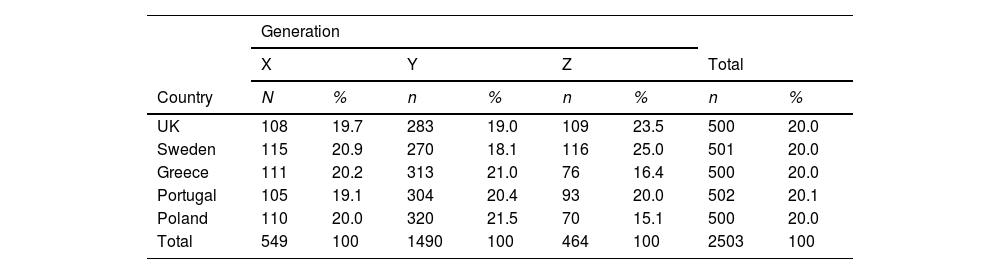

SampleThe demographic distribution of the study participants was geographically balanced, with each of the five countries contributing 20 % to the overall sample (2503 participants). The gender representation was nearly equal, with 50.4 % of the participants being men and 49.6 % women.

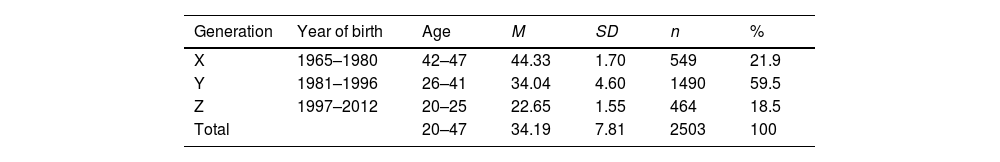

Table 2 depicts the age distribution in the current sample.

Age distribution.

| Generation | Year of birth | Age | M | SD | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | 1965–1980 | 42–47 | 44.33 | 1.70 | 549 | 21.9 |

| Y | 1981–1996 | 26–41 | 34.04 | 4.60 | 1490 | 59.5 |

| Z | 1997–2012 | 20–25 | 22.65 | 1.55 | 464 | 18.5 |

| Total | 20–47 | 34.19 | 7.81 | 2503 | 100 |

M – mean value; SD – standard deviation; n- number of respondents; % - sample percentage.

The participants’ age range was 18 to 45 years, with the most significant proportion (39.2 %) falling within the 36–45 age bracket. Most respondents were aged 26–41 and represented Generation Y. Table 3 depicts the number of respondents from each country.

Country distribution.

n- number of respondents; % - group percentage.

In terms of educational attainment, most of the respondents (53 %) possessed a higher education degree, including a bachelor's, master's or doctoral degree.

Most respondents from generations X and Y had obtained university degrees, whereas those from Generation Z had completed secondary education. Furthermore, most of them studied social sciences and business and law. In 642 cases (25.6 %) – 108 cases regarding Generation X (19.7 %), 372 cases regarding Generation Y (25.0 %) and 162 cases regarding Generation Z (34.9 %) – the participants’ work or education was linked to their natural environment. Therefore, most of the respondents were full-time employed.

Finally, a significant majority of the participants (73.4 %) reported that their occupation or educational background was not directly related to environmental fields.

Data analysisFirst, we analysed descriptive statistics for all interval variables in terms of distributions, composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE). Second, we verified correlation coefficients between environmental awareness, creativity, risk-taking propensity, proactive coping and pro-environmental innovative behaviour, both passive and active. Furthermore, we used a model in which environmental awareness, creativity, risk-taking propensity and proactive coping were analysed as predictors of passive and active pro-innovative behaviours with the use of a path analysis. Furthermore, we tested the invariance of the final model acquired regarding the differences between the generations. Finally, we analysed the differences between generations X, Y and Z in terms of the levels of environmental awareness, creativity, risk-taking propensity, proactive coping and passive and active pro-innovative behaviours using analysis of variance.

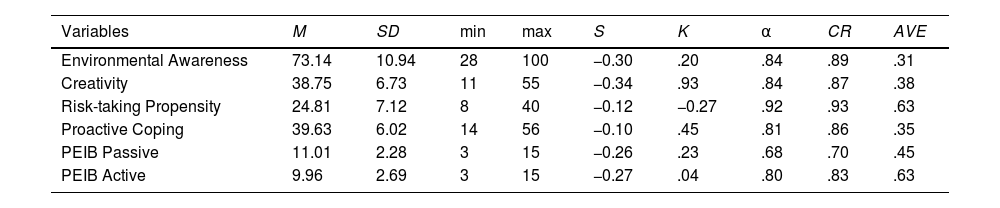

ResultsTable 4 provides a comprehensive overview of the descriptive statistics for the analysed interval variables – specifically, mean values, standard deviations, minimum and maximum values and measures of skewness and kurtosis. Moreover, it provides Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficients, CR and AVE.

Descriptive statistics for analysed interval variables.

M – mean value; SD – standard deviation; min – minimum value; max – maximum value; S – skewness; K – kurtosis; α – Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficient, CR – composite reliability; AVE – average variance extracted. All values of composite reliability were satisfactory. However, the AVE for creativity, proactive coping and Passive PEIB was below 0.5.

Both skewness and kurtosis for all the analysed variables fall in the range [−1; 1] characteristic of normal distribution. Since we performed the analysis on a large sample of 2503 participants, significant results of normality tests, such as the Shapiro-Wilk test or Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, would still be derived even in the case of a small deviation from normality (Field, 2009; Ghasemi & Zahediasl, 2012; Oztuna et al., 2006). Therefore, we applied skewness and kurtosis to assess normality. Moreover, the sampling distribution tends to be normal, regardless of the shape of the data (Field, 2009; Ghasemi & Zahediasl, 2012).

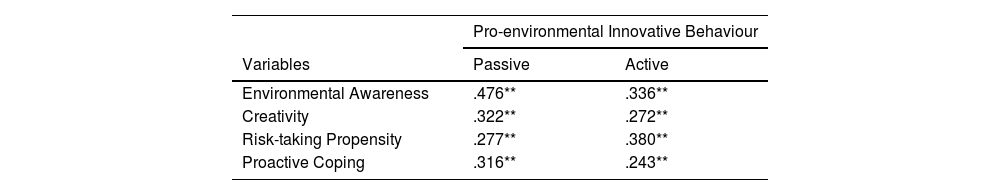

Table 5 presents Pearson's correlation coefficients between environmental awareness, creativity, risk-taking propensity, proactive coping and pro-environmental innovative behaviour, both passive and active.

Environmental awareness, creativity, risk-taking propensity and proactive coping were positively correlated with pro-environmental innovative behaviour of both types (passive and active). The presented findings suggest that these variables are important factors in predicting the likelihood of engaging in pro-environmental behaviours that are innovative, both in passive and active forms. Finally, the significance levels (p < .01) of all correlations indicate a high level of confidence in these results.

Model of relationships between the analysed variablesWe analysed environmental awareness creativity, risk-taking propensity and proactive coping as predictors of passive and active pro-environmental innovative behaviours. Therefore, correlations between these predictors as well as between both variables explained here were also included in the model; that is why the conducted analysis was based on a path rationale. Fig. 1 depicts the analysed preliminary model.

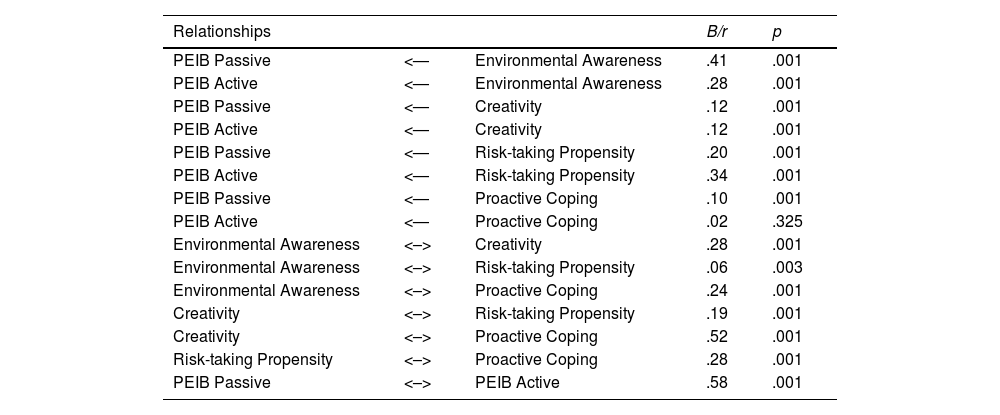

The analysis was based on the maximum likelihood method. Table 6 depicts the results acquired.

Regression coefficients acquired in the path analysis.

B – standardized regression coefficients; r – Pearson's correlation coefficient; p – statistical significance.

Of all the relationships tested, only one was statistically insignificant, that is, the relationship between proactive coping and active pro-innovative behaviours. This relationship was removed, and the model's fit to the analysed data was close to perfect. The values of fit indices were equal to NFI = 0.99, CFI = 0.99 and RMSEA = 0.01.

In the following step, we verified the model's invariance to detect the possible differences between the three generations regarding the examined associations between variables. Therefore, the differences regarding the regression coefficients were statistically insignificant, χ2(14) = 17.89, p > .05, ΔNFI = 0.01. Conversely, the covariances included in the model showed statistically significant differences, χ2(32) = 133.46, p < .001, ΔNFI = 0.03.

Based on the presented study, we examined the values of Pearson's correlation coefficients acquired in the three groups of participants representing three generations. Additionally, we determined the values of Fisher's transformation for assessing the statistical significance of the differences between correlation coefficients. As a result, the positive correlation between risk-taking propensity and proactive coping was significantly stronger in the group of participants from Generation X than in the group of participants from Generation Y. Furthermore, the positive correlation between environmental awareness and proactive coping was significantly stronger in the group of participants from Generation Z than in the group of participants from Generation Y.

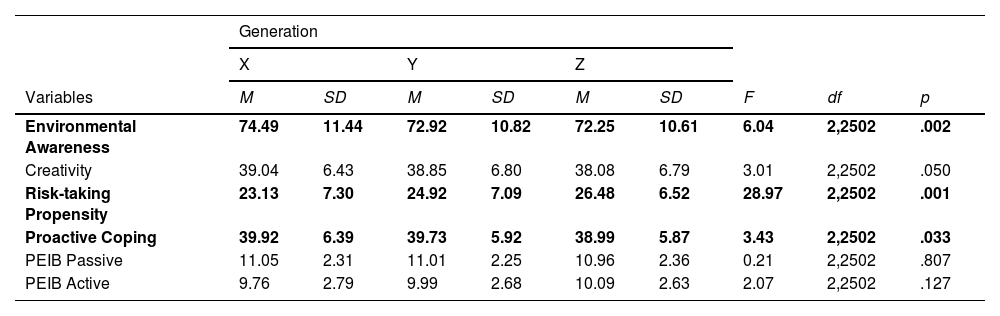

The groups of participants from the three generations were also compared in terms of mean values of each of the variables analysed. Table 7 presents the mean values of the analysed variables as well as the values of the so-called one-way analysis of the variance test used for testing the statistical significance of the differences between the three groups of participants.

Mean values of the analysed variables in the groups of participants from Generations X, Y, and Z.

M – mean value; SD – standard deviation; F –analysis of variance test value; df – degrees of freedom; p – statistical significance.

We also detected statistically significant differences regarding environmental awareness, risk-taking propensity and proactive coping. According to the values of Gabriel's post-hoc test, the mean value of environmental awareness was significantly higher in the group of participants from Generation X than in the groups of participants from Generation Y, t = 2.88, p < .01, and Generation Z, t = 3.25, p < .01. Conversely, the mean value of risk taking propensity was higher in the group of participants from Generation Z than in the groups of participants from Generation X, t = 7.56, p < .001, and Generation Y, t = 4.18, p < .001. Furthermore, the mean value of risk-taking propensity was also higher in the group of participants from Generation Y than in the group of participants from Generation X, t = 5.10, p < .001. In turn, the mean value of proactive coping was significantly lower in the group of participants from Generation Z than in the groups of participants from Generation X, t = −2.43, p < .05, and Generation Y, t = −2.31, p < .01.

To sum up, the presented results reveal several key insights. First, the moderate positive correlation between environmental awareness and creativity across all generations suggests a link between environmental awareness and creativity. This could mean that increasing environmental awareness might also enhance creative thinking. Furthermore, the weak positive correlation between environmental awareness and risk-taking propensity, particularly in Generation X, indicates that while a link exists between environmental awareness and risk-taking, it is not strong. This might suggest that environmental initiatives or campaigns that require a high degree of risk-taking may not appeal broadly across generations. Conversely, the positive correlation between environmental awareness and proactive coping, which is especially strong in Generation Z, implies that younger individuals who are environmentally aware are also more likely to engage in proactive coping. That is why the positive correlation between creativity and risk-taking propensity across generations suggests a link between creativity and willingness to take risks. Finally, the strong correlation between creativity and proactive coping indicates that creative individuals are likely to be good at proactive coping. A different strength of correlation is also observed between risk-taking propensity and proactive coping across generations.

DiscussionIn the context of this investigation, we have operationalized a theoretical model with four antecedent variables of pro-environmental innovative behaviour. However, in delineating the contours of pro-innovative behaviours, the literature has identified key antecedent characteristics: risk-taking propensity, proactive coping and creativity (conceptualized in this study as ‘self-initiative behaviour’). These dimensions have been empirically validated as pivotal in fostering pro-innovative tendencies (Zhang & Ma, 2019). More specifically, the propensity to engage in risk-taking has been correlated with innovation and innovative behaviours in extant research (Cropley, 2002; Miron et al., 2004). Concurrently, the trait of proactivity in individuals has been empirically linked to pro-innovative behaviours (Parker et al., 2006). Moreover, the construct of creativity is viewed as a fundamental catalyst for innovation, engendering novel behaviours among individuals. This is substantiated by research delineating a positive relationship between creativity and innovation, positioning the former as an antecedent to the latter (Hammond et al., 2011; Miron et al., 2004). Nonetheless, given the specific orientation of pro-environmental innovative behaviour towards innovative behaviours that engender pro-environmental outcomes, elucidating the interface between environmental innovation and awareness is imperative. Consequently, this paper also endeavours to articulate and empirically test the link between pro-environmental innovative behaviours and environmental awareness.

The study's findings on generational differences in environmental awareness, creativity, proactiveness and risk-taking provide valuable insights into how these constructs evolve across age cohorts. These correlations suggest that individuals who are more environmentally aware, creative, willing to take risks and capable of proactive coping are more likely to engage in behaviours that promote environmental innovation.

That is why the representatives of Generation X revealed the highest level of environmental awareness, while Generation Z exhibited higher propensity for risk-taking than Generations X and Y. This suggests that younger individuals might be more willing to engage in behaviours that involve uncertainty, which could foster innovation. In turn, Generation Z demonstrated lower levels of proactive coping compared to Generations X and Y, which means that younger individuals might need more support when developing proactive coping actions.

The positive correlation between risk-taking propensity and proactive coping is stronger in Generation X than in other generations. This indicates that Generation X individuals, who are inclined to take risks, are also more likely to engage in proactive coping strategies, which could lead to higher levels of innovative behaviour. Conversely, the positive correlation between environmental awareness and proactive coping is articulated more vividly in Generation Z compared to Generations Y and X. This suggests that younger individuals who are aware of environmental issues are also more likely to adopt proactive coping mechanisms.

As a result, the abovementioned data align with the literature suggesting that generational identity significantly influences attitudes and behaviours (Smith, 2020). The study extends this perspective by linking these attitudes specifically to pro-environmental innovative behaviours. The observed positive correlations between environmental awareness and pro-environmental innovative behaviours across generations support the notion that increased environmental consciousness leads to proactive actions. This study further deepens this understanding by analyzing these relationships across generational segments.

ConclusionsThe presented study utilized a path analysis based on the maximum likelihood method to examine the relationships between environmental awareness, creativity, risk-taking propensity and proactive coping as predictors of pro-environmental innovative behaviours. It proved that significant correlations exist between environmental awareness (H1), creativity (H2), risk-taking propensity (H3), proactive coping (H4) and pro-environmental innovative behaviours. The study revealed statistically significant differences in covariances between generations, thus providing an answer to the research question (RQ). Notably, the positive correlation between risk-taking propensity and proactive coping was significantly stronger in Generation X than in Generation Y. Additionally, the positive correlation between environmental awareness and proactive coping was significantly stronger in Generation Z than in Generation Y. Furthermore, statistically significant differences were also found in the mean values of environmental awareness, risk-taking propensity and proactive coping across the generations. In other words, Generation X showed higher environmental awareness than Generations Y and Z, while risk-taking propensity was higher in Generation Z compared to Generations X and Y. Generation Z also showed lower proactive coping compared to the other two generations. The study's findings highlight significant generational differences in how environmental awareness, risk-taking, creativity and proactive coping are interrelated. This suggests that when it comes to encouraging innovative behaviours and environmental consciousness, a tailored approach may be required for each generation. For instance, strategies that work for Generation X, who exhibit higher environmental awareness, might not be as effective for Generation Z, who show a higher propensity for risk-taking but lower proactive coping.

Limitations and future researchThe study's categorical approach to generations might have overlooked the nuances within and overlap between these groups as generational boundaries are not always clear-cut. The cross-sectional nature of the study limits its ability to capture the evolution of these traits over time. Future research could adopt a longitudinal approach to track changes in these psychological constructs within individuals across different life stages. While the study included a diverse range of countries, expanding it to include more varied cultural contexts could enhance the generalizability of the findings.

The presented study suggests paths for further research to explore the underlying factors contributing to these generational differences. Future studies could investigate the role of socioeconomic, technological and cultural influences in shaping pro-innovative behaviour across generations. Additionally, longitudinal studies could provide insights into how these traits and their interrelations evolve over time within individuals and across generations.

ImplicationsThe study's findings offer valuable insights into the complex interplay of environmental awareness, creativity, risk-taking propensity and proactive coping in predicting pro-environmental innovative behaviours across generations. Theoretical models in environmental psychology and related fields should incorporate these generational differences to better explain and predict pro-environmental behaviour. By acknowledging the unique psychological and behavioural profiles of different generations, researchers and theorists can develop more comprehensive and generationally sensitive frameworks, ultimately enhancing the understanding of how to foster sustainable and innovative behaviours across diverse demographic groups. These theoretical implications pave the way for future research that can explore tailored interventions and educational strategies to effectively promote environmental sustainability.

The study offers considerable implications for designing targeted environmental policies and educational programmes. Therefore, understanding the varying relationships between the analysed constructs across generations can help design age-specific interventions and policies. Environmental campaigns could be tailored differently for each generation, emphasising proactive coping in younger generations and leveraging the higher environmental awareness in older generations. In multi-generational workplaces, this knowledge can be used to foster better collaboration and understanding, recognising that risk-taking and proactive coping may vary across age groups.

Finally, the findings can inform the development of educational curriculums and programmes that cater to the specific needs and strengths of different age groups, particularly in fostering creativity and innovative behaviours. This can inform multinational organizations and policymakers about ways of tailoring their strategies and policies to different generational settings.

Ethics approvalWe certify that the submission contains all original work and is not under review at any other journal. We collected all data in a manner consistent with ethical standards for the treatment of human subjects.

CRediT authorship contribution statementMałgorzata Baran: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Barbara Sypniewska: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

The research was supported by Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange (grant number: PPI/APM/2019/1/00096/DEC/01).