Migrant entrepreneurship involves the indigenous population and migrant communities, exerting a profound influence on the host country or region. This phenomenon is particularly relevant in ultraperipheral areas, as in this research exemplified by the Autonomous Region of Madeira (Madeira), which recently witnessed an intensification of migrant inflow, many originating from countries with a deep historical connection to the region.

This research characterizes the entrepreneurial migrant community to discern factors that may contribute to formulating and enhancing political-social policies to foster entrepreneurship success, broadly relevant to generating wealth but of particular importance in facilitating migrants’ integration. The analysis focuses on understanding the motivations that drive entrepreneurial initiatives among migrants, recognizing the predominance of necessity-driven entrepreneurs, and that migrant entrepreneurs often take advantage of historical and familial ties to the region to overcome the obstacles specific to migrants.

In recent decades, the significance of entrepreneurship and the essence of being an entrepreneur have gained increasing attention across various research domains and disciplines. As a result, politicians, economists, educators, and society in general have increasingly come to understand and value the role of entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship is associated with innovation, initiative, the possibility of doing something new or different, and the ability to take risks. Governments, understanding the type of entrepreneur, can establish incentives and support, thus helping the growth of entrepreneurial activity and the economy.

Migrant entrepreneurship has become an increasingly relevant research topic. However, research on this topic is still scarce (Liu, Liang & Chunyu, 2023; Mayuto et al., 2023). For the host country or region, the increase in migratory movement requires policies supporting job creation, resources and knowledge transfer, and competitiveness. For migrants, who are more prone to start a business than natives, entrepreneurship provides more job opportunities. It facilitates their integration, greater social mobility, and better living conditions (GEM, 2012; Liu et al., 2023). However, compared with the native community, migrant entrepreneurs (MEs) generally experience more difficulties creating and maintaining their businesses due to financial capital restrictions, lack of familiarity with the functioning of the local market, and challenges in understanding the regulatory structures (Desidério, 2014).

Furthermore, ultraperipheral regions present structural weaknesses in their economies. These weaknesses are visible in the public sector's significant weight, relatively low income level per inhabitant, trade gaps, over-specialized agricultural production, excessive dependence on specific sectors, such as tourism, insufficient R&D expenditure, or difficulties adapting to the liberalization of the global markets. In the case of Madeira, a significant number of immigrants have origins in the region due to the history of emigration in the second half of the 20th century to countries such as Venezuela, Brazil, and South Africa. Due to the deterioration of the socioeconomic conditions in those countries, in recent years, there has been a change in the migratory path.

This work focuses on understanding the factors that influence entrepreneurship – opportunity or necessity-driven – involving formal government support and informal support from family members in a European ultraperipheral region. Based on the research model and focusing on migrant entrepreneurship, the following objectives were defined: 1) Analyze the migrant entrepreneurship characteristics in this ultraperipheral region; 2) Analyze the factors leading to opportunity-driven entrepreneurship; 3) Analyze the factors that influence necessity-driven entrepreneurship; 4) Analyze the influence of formal government support; 5) Analyze the influence of migrants’ previous entrepreneurial experience; 6) Analyze the influence entrepreneurs’ gender.

Literature reviewEntrepreneurship, entrepreneurs and migrant entrepreneursEntrepreneurship refers to “any attempt to create a new business or new initiative, such as self-employment, a new business organization, or the expansion of an existing business, by an individual, a team of individuals, or a business established” (GEM, 2012:21). Stevenson and Jarillo (1990) consider entrepreneurship as a process by which promoters, one or several individuals, or an organization do everything to carry out the project, regardless of the organizational context.

Murphy, Liao and Welsch (2006)) argue that entrepreneurship is one of the main drivers of economic growth, using the flow of innovations to develop new technologies and products or services. In the process of establishing their business, entrepreneurs take advantage of their qualities of creativity and innovation, administrative skills and business knowledge, optimism, and emotional resistance, work capacity prone to effort and sacrifices, intense commitment to the project, perseverance, and the desire to consistently achieve more and better (Coon, 2004). To maintain a profitable and evolving business, for example, entrepreneurs take advantage of their desire to evolve, innovate, and improve; the desire to change their lives and chart their courses; the desire to win; and characteristics of self-confidence, perseverance, flexibility, and self-esteem (Rodrigues, 2008).

Compared to the native population, migrants – who voluntarily move to another country or region to improve their material and social conditions and those of their families – are more likely to start businesses. This characteristic has implications, for instance, for host country investors, to respond more to the phenomenon by better adapting the services they offer to the needs of MEs (Vandor, 2021). We need, however, to recognize that for migrants, the decision to start a business may be a way to facilitate their integration (GEM, 2012). Yet MEs must still overcome several challenges (Desidério, 2014) and liabilities of foreignness in the host country (Mayuto, Su, Mohiuddin & Fahinde, 2023).

Necessity- and opportunity-driven entrepreneurshipThe entrepreneur's (either native or migrant) motivation determines the main difference between types of entrepreneurship (Amorós, Borraz & Veiga, 2016). Fairlie and Fossen (2018), as is common in literature, distinguish between those entrepreneurs who take advantage of opportunities to create their businesses – opportunity-driven entrepreneurs – and those who start a business forced by necessity – necessity-driven entrepreneurs –, usually because they do not find options in the job market. Necessity-driven entrepreneurs generally refer to unemployed individuals and opportunity entrepreneurs as those who choose to create their projects by giving up their jobs or taking advantage of their student status by starting a business.

Fairlie and Fossen (2018, 2020) state that necessity-driven entrepreneurs are more likely to find quick solutions in contexts of low barriers to entry and in growing sectors. Opportunity-driven entrepreneurs have a desire for independence, greater risk propensity, high need for achievement, and preference for innovation, and are more likely to open businesses in sectors with higher barriers to entry, as these present better opportunities and potential for generating results (Barba-Sánchez & Atienza-Sahuquillo, 2017).

According to Calderon, Iacovone and Juarez (2016), opportunity-driven entrepreneurs differ in several dimensions from necessity-driven entrepreneurs, as opportunity-driven entrepreneurs are more capable of identifying a good opportunity, even in emerging markets, and because they consider the option more advantageous. Opportunity-driven entrepreneurs are able to obtain better results and better performance from their employees due to better management practices and because they are more motivated to succeed in their ventures. Opportunity-driven entrepreneurs are also better positioned to face an external or social change in the demand for goods and services or a change in the availability of capital. These entrepreneurs begin with the intention of exploring an opportunity, taking advantage of the conditions arising in the market that lead them to entrepreneurial activity. Necessity-driven entrepreneurs become entrepreneurs due to a lack of other alternatives, which do not always correspond to what they really want, sometimes leading them to make less successful choices.

Migrant entrepreneurship factorsFactors related to the home countryPrevious research reveals a connection between the factors in the home country and migrant entrepreneurship. Home country factors are related to obstacles and facilitators inherent to government policies and the entrepreneurship environment. The Chinese government's “One Belt, One Road” policy, through which businesses are encouraged to engage in internationalization (Duan, Kotey & Sandhu, 2021), exemplifies the facilitator policies. In the case of Lebanese MEs in Canada (Chababi, Chreim & Spence, 2017), entrepreneurs’ experiences and identification of opportunities are shaped by war in the home country with limited politico-legal structures to support entrepreneurship, compared with a country that offers these structures. The analysis of Canadian transnational entrepreneurs (Nkongolo-Bakenda & Chrysostome, 2019) revealed that the main home country obstacles to start-up and growth of businesses are taxes, regulations, corruption, lack of financial resources, and lack of qualified human resources. In a study of immigrant-owned firms in the Italian information and communications technology sector, Brzozowski, Cucculelli and Surdej (2014) concluded that home-country factors related to socioeconomic characteristics (level of entrepreneurial endowment, macroeconomic stability, level of corruption, and level and quality of education), and its entrepreneurial attitude (need for achievements, uncertainty avoidance, locus of control and long-term orientation), are reflected in the effect of the transnational network on the performance of immigrant enterprises.

The practical consequences of the home country context are diverse. For example, Polish MEs in Glasgow (Lassalle, 2018) take advantage of their perception and flair to recognize opportunities within the local structure despite their lack of experience or knowledge in the sector. In turn, Indian MEs in the USA (Pruthi, Basu1 & Wright, 2018) who acquired prior experience doing business with India use ethnic professional and alumni ties to establish a direct presence in the home country. In the case of MEs with little or no prior experience doing business with their home country, family ties are reflected in emotional and non-economic reasons for becoming entrepreneurs. In time, their work experience, mainly at start-ups in the USA, builds their motivation and confidence to create a venture independently. As for Chinese immigrants in Australia and New Zealand (Duan et al., 2021), crucial ways to finance new businesses in the host country consist of personal funding methods in the home country through selling previous companies or existing firms in China, savings, or family support.

Facilitators and obstacles in the host countryFacilitators in the host country comprise institutional conditions and the entrepreneuship environment. For example, MEs originating from Sweden and Finland praised the normative and regulative institutional conditions in Hong Kong, albeit having identified opportunities inherent to the neighboring mainland China (Lundberg & Rehnfors, 2018). Similarly, first-generation Lebanese MEs in Canada highlighted the stability of the host country, the regulatory framework favoring the protection of entrepreneurs’ rights, and the simplicity of legal transactions as enablers (Chababi et al., 2017).

Based on a longitudinal database on immigration in Canada, Li (2001) concluded that better self-employment odds occur for those migrants who have better educational qualifications, arrive in Canada in better economic times, and are selected to enter Canada for their human capital. Also studying MEs in Canada, Nkongolo-Bakenda and Chrysostome (2019) found that the most frequently mentioned factors related to start-up creation and development were the government programs and services supporting immigrant organizations, local community tolerance, and recognition and validation of credentials from the home country. An analysis of immigration and entrepreneurship in Greece (Skandalis, 2014) showed that the host nation's institutional support and market conditions motivated immigrants to start a new business.

Obstacles in the host country are often associated with socioeconomic and racial segregation, government policies, and cultural distance. In the study of African MEs in South Africa, Griffin-el and Olabisi (2018) concluded that residents become suspicious of – and insular towards – foreigners’ businesses in a host country characterized by high income inequality. MEs feel themselves as the social ‘outsiders’ due to their lack of attachment to prevailing beliefs about business, socioeconomic status, and racial segregation. The analysis of Eritrean MEs in the UK reveals that obstacles and discrimination come from the UK community and regulatory bodies (Hagos, Izak & Scott, 2019). MEs working in the care sector in Poland highlighted the main barriers to entrepreneurship, referring to current legal status, financial barriers, lack of language skills, and parental status (Maj & Kubiciel-Lodzinska, 2020). In the statistical analysis of MEs in the Netherlands (Beckers & Blumberg, 2013), the cultural distance to the host country is more significant for the clusters of Turkish, Moroccan, and Chinese migrants than those from former colonies.

Characteristics of MEsBehavioral characteristics of MEs explain engagement in self-employment and entrepreneurial intentions. Analysis of longitudinal data on immigration in Canada reveals that the longer immigrants have been in Canada, the higher the likelihood of engagement in self-employment (Li, 2001). Skandalis (2014) identified the importance of self-motivation and other personal needs of MEs in Greece. They have innate personal characteristics that help identify a new opportunity in their host nation while bringing business-related know-how.

The characteristics of MEs provide evidence to compare MEs with native entrepreneurs. In their study of successful Canadian and US immigrant entrepreneurs, Sundararajan and Sundararajan (2015) found that MEs were more successful in starting their new business than host country entrepreneurs due to boundary spanners in two or more cross-country embedded social networks in terms of self-employment experience, knowledge, access to new information, available contacts and money. MEs owning SMEs in Paris, Frankfurt, Milan, Madrid, and London have a lower propensity to plan and a lower performance level than native SMEs’ owners due to unfamiliarity with the institutional and economic contexts in the host country (Campagnolo et al., 2022). The support immigrant entrepreneurs get in their social network of compatriots results in an informal way of doing business that reduces immigrant-led SMEs’ capacity to deal with crises and to grow under ‘normal’ circumstances (idem).

The study of MEs in the Netherlands states that educational achievements from colonial origin are similar to those of the native population. However, due to the group's labor market disadvantages, entrepreneurial success rates are lower (Beckers & Blumberg, 2013). In a statistical analysis of MEs in the USA, Wang and Liu (2015) found that, when compared to non-immigrant-owned firms, ME-owned firms have a significantly higher tendency to be involved in transnational economic activities, and that these firms are managed in a “low-cost” way characterized by higher sales and fewer employees.

Behavioral characteristics of MEs are related to opportunity recognition processes. Polish MEs’ flair in Glasgow regards the ability to spot opportunities in the community niche market in the context of a new opportunity in the host country, developed by gradual knowledge accumulation (Lassalle, 2018). Practical heuristics, undocumented processes of research, and intuition are their basis for decision-making. In time, the opportunity recognition process is repeated at various business development stages as MEs accumulate experience (idem). MEs from Sweden and Finland in Hong Kong value knowledge of the institutional context of the host country in terms of working and living there before starting their ventures, and thus, the identification of a broader range of opportunity types is facilitated compared with migrants with lesser human capital (Griffin-el & Olabisi, 2018). A study of migrant tourism entrepreneurs in peripheral rural areas of Norway concluded that migrants incorporate their favorite leisure activities into their business operations. A crucial motivation behind the migration was a desire for a lifestyle change reflected in reducing everyday stress, residing in a cleaner and healthier environment, and well-being (Iversen & Jacobsen, 2016). Yet, before deciding on a location, no MEs had undertaken any market research and based their decisions on gut feeling (idem). The analysis of MEs in Turkey concluded that their unique human capital is the ability to identify opportunities based on the knowledge of their home country's market, familiarity with the local market, and understanding of the host country's culture, religion, and language (Shinnar & Nayır, 2019).

Knowledge acquisition and family supportMEs’ education can directly or indirectly affect entrepreneurship dynamics. MEs from Sweden and Finland in Hong Kong had been studying in Asia and regarded this educational knowledge as the basis for business and entrepreneurship (Lundberg & Rehnfors, 2018). Yet, the absence of education effects may be explained by their international orientation (traveling a lot, previous work or study experiences from Hong Kong and mainland China) before starting their ventures (idem). Chrysostome and Arcand (2009) concluded that higher educational levels influence business survival for Latin American necessity-driven MEs in Canada.

Prior work experience, professional and family ties, and interaction with ethnic communities influence MEs’ activities in a host country. While the first typology of Indian MEs in the USA, based on prior work experience or professional ties, uses alumi ties to provide approval to professional ties, the second MEs typology relies on trustworthy family ties to provide functional skills, physical infrastructure or local market knowledge (Pruthi et al., 2018). The third MEs’ typology establishes trust over time by validating ethnic skill sets through an Internet search (idem). Mexican and Columbian MEs in Sweden show that entrepreneurial orientation development trajectories vary in the presence of family roles, so the reduction of MEs’ sense of risk, which enables risk-taking, is provided by family backing (Ljungkvist, Evansluong & Boers, 2023). Turkish and Moroccan communities in the Netherlands are large and centered around the major cities. These communities acquire a high level of local self-sufficiency associated with the numerous Turkish and Moroccan cultural associations and within local business landscapes formed by many firms serving the specific needs of co-ethnic communities (Beckers & Blumberg, 2013). According to the authors, this situation negatively impacts firm development prospects. The Chinese community also has a strong own-group orientation and identification. However, it is less self-sufficient as it spreads widely across the country and is a smaller group (idem). For MEs in Turkey, the social capital perceived as an advantage did not result from membership in professional associations but from interpersonal relationships and family ties (Shinnar & Nayır, 2019).

Propositions and research modelIn sum, home country factors encompass prior entrepreneur success and previous knowledge and experience. The home and host countries show facilitators and obstacles associated with government policies, the entrepreneurship environment, socioeconomic characteristics, cultural distance, and socioeconomic and racial segregation. Behavioral characteristics of MEs explain engagement in self-employment, and opportunity recognition processes provide evidence to compare MEs to native entrepreneurs and first- and second-generation MEs. Behavioral characteristics are also inherent in market inclusion and co-ethnic preferences for targeting customers. In the host country, MEs’ knowledge and experience are associated with prior work experience, professional, family, and ethnic community ties, socioeconomic integration, specific characteristics of first- and second-generation, and educational factors that directly and indirectly affect self-employment dynamics.

Considering the reported differences between opportunity- and necessity-driven entrepreneurship and the fact that these differences are relevant and potentially influence business success, we focus on the underlying factors to understand how different factors combine according to the entrepreneurship type. Therefore, we formulate the following research proposition:

P1 There are multiple configurations of factors (equifinality) leading to opportunity- and necessity-driven migrant entrepreneurship, and those configurations differ according to the type of entrepreneurship.

Based on the literature review, we consider the importance of three control variables to understand how government support, prior entrepreneurial experience, and gender interconnect with the configurations leading to opportunity- and necessity-driven entrepreneurship outcomes. Nkongolo-Bakenda and Chrysostome (2019) notice that starting and growing a business is impacted by facilitating factors such as government support programs. MEs from Sweden and Finland in Hong Kong (Lundberg & Rehnfors, 2018) also had previous experiences as entrepreneurs or business knowledge developed in an entrepreneurial environment, which shows a positive stance about starting their businesses. MEs that had successful businesses before migration established their Australian businesses due to their desire to settle in the host country and expand their firms (Duan et al., 2021). Previous literature has also addressed the pre-migration business experience of Chinese MEs (Liu et al., 2023). Male immigrants are more likely to be self-employed than female immigrants (Li, 2001), and this may be due to several reasons, including family dynamics, culture-related roles and expectations, and human capital (Mindes & Lewin, 2024). Based on these arguments, we formulate the following research propositions:

P2 Formal government support influences the configurations of migrant entrepreneurship factors leading to opportunity- and necessity-driven entrepreneurship.

P3 Previous entrepreneurial experience influences the configurations of migrant entrepreneurship factors leading to opportunity- and necessity-driven entrepreneurship.

P4 Gender influences the configurations of migrant entrepreneurship factors leading to opportunity- and necessity-driven entrepreneurship.

The underlying proposed research model is represented in Fig. 1.

MethodologyConstructs and variablesConsidering the above research model and propositions, based on the previous literature, the constructs and variables selected for this research are as follows (Table 1):

Constructs and variables.

This study on migrant entrepreneurship focuses on businesses based in Madeira owned by migrants as units of analysis. In 2019, there were 9455 foreign citizens registered (Direção Regional de Estatística da Madeira, 2021). In the same year, there were 28,905 firms based in Madeira, but more than 96 % were micro-enterprises. In the absence of a specific database identifying MEs in Madeira, a local researcher developed direct contacts with known MEs and groups or communities of MEs in Madeira. These initial contacts facilitated access to other MEs in a snowball sampling procedure. All MEs identified through this procedure were invited to participate in the study. Data was collected through a questionnaire that included closed and open questions and was sent out to migrants operating their businesses. For closed questions, a scale from 1 to 10 was used (1 representing no influence and 10 representing exceptional influence). In total, ninety-six MEs answered the questionnaire in such a way as to consider the responses valid.

The first step in the data analysis consisted of descriptive statistics. Based on the descriptive analysis, in section 4.1, we present a thorough analysis of the MEs that responded to the questionnaire, thus helping to understand the profile of MEs in Madeira, the ultraperipheral region we chose to analyze in this research. Considering our research objectives, our research model, and the variables’ characteristics, for the following step in the data analysis, we elected fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) (Fiss, 2011), which enables the identification of configurations of conditions leading to the type of entrepreneurship outcome (opportunity- vs. necessity-driven). FsQCA allows for obtaining consistent solutions using small samples and benefits from equifinality literature, highlighting that the same outcome is reachable through different configurations of conditions (Ragin & Fiss, 2008). FsQCA is nowadays a consolidated data analysis methodology included in the spectrum of Qualitative Comparative Analysis that, as Huang, Li, Chen and Wang (2023) note, combines features of qualitative data analysis with features of quantitative data analysis and has been previously been used in the context of entrepreneurship research (e.g., Huang et al., 2023; Kusa, Duda & Suder, 2021; Yao & Li, 2023).

One of the relevant steps during the analysis is calibrating the variables (Huang et al., 2023) into conditions and outcomes ranging from 0 to 1, which stand for fully out and fully in. Gender was calibrated by assigning 0 to men and 1 to women. Regarding the variable PEE (Previous Entrepreneurial Experience), we opted for a direct calibration using the thresholds 10, 5.5, and 1. Finally, we considered the 90 %, 50 %, and 10 % percentiles as thresholds for fully in, maximum ambiguity, and fully out for the remaining variables. The conditions were calibrated (Ragin, 2008) after determining the consistency of the independent constructs Home Country Context (HmCC) (α=0.80), Barriers in the Host Country (BHC) (α=0.79), Individual Characteristics (IC), Knowledge Acquisition (KA), and Family Support (FS) (α=0.75). Likewise, the outcome was calibrated after determining the consistency of Opportunity-driven Entrepreneurship (OE) (α=0.83). The calibration thresholds are presented in Table 2.

After calibrating the variables, we identified all the maximum ambiguity values (0.5) in our database and replaced those with 0.499, thus avoiding the loss of cases. With the new database, we moved to the necessary conditions analysis. Necessary conditions analysis aims to identify conditions that are necessary for a specific outcome to occur. A condition is almost always necessary if the consistency is equal to or above 0.80 and necessary if the consistency is equal to or above 0.90. Out data reveals that no condition is necessary or almost always necessary for the presence of the outcomes (opportunity-driven entrepreneurship). However, focusing on the absence of the outcome (representing necessity-driven entrepreneurship), we found that the absence of previous entrepreneurial experience (∼PEE) is almost always necessary (consistency of 0.89), which is a valuable insight related to first-time necessity-driven entrepreneurs.

The subsequent step in fsQCA consists of the sufficiency analysis. Sufficiency analysis allows the identification of configurations of conditions leading to a specific outcome. It is deeply associated with the idea that: i) multiple configurations may lead to a specific outcome (equifinality); and ii) the inverse of the configurations leading to a specific outcome may not lead to the absence of the same outcome (asymmetry). The researchers must make several decisions to conduct the sufficiency analysis, including the cutoff point in the truth table. According to Schneider and Wagemann (2012), researchers should consider consistency and proportional reduction to determine the cutoff point. The sufficiency analysis provides three solutions: complex, intermediate, and parsimonious. We report the intermediate solution considering the usual minimum value of 0.75 for the consistency of the solutions (Schneider & Wagemann, 2012).

Analysis and resultsDescriptive statisticsOf the 96 respondents, 52.1 % were male, and most MEs were between 30 and 45 years old. The country of origin with the most respondents is Venezuela (41.7 %), followed by Brazil (18.8 %) and South Africa (9.4 %). However, 25 % of MEs, despite living abroad before migrating to Madeira, retained their Portuguese nationality. Finally, four respondents had dual nationality. Regarding marital status, 52.1 % were married or living in a non-marital partnership, 35.4 % were single, and only 2.1 % were widowed. Of those married or living in non-marital partnerships, 18 % of respondents responded that their partners also work in their business. Consistent with the respondent's age and marital status, 65.6 % had children.

Focusing on the highest education level, 31.3 % of the MEs reported the 12th year of schooling, 20.8 % the 9th year of education, 17.7 % a bachelor's degree, 7.3 % a master's degree, and 1.04 % a Ph.D. Besides this education, 18.8 % of respondents attended at least one technological or professional training program. As for the impact of their education in starting a business, 65.6 % claimed that it wasn't helpful, 25 % responded that it was relevant, and the remaining stated that it may have helped. Of those who believe that their qualifications facilitated starting a business, nine attended a technological or professional program, six had a bachelor's degree, four had a master's degree, one had a Ph.D., three completed the 12th grade, and one completed the 9th grade. As for the reasons why educational qualifications were useful, the MEs answered that without this education it would be almost impossible to start a business and that their academic qualifications gave them more confidence and passion. Furthermore, the qualifications helped them to understand the market better and to obtain relevant contacts for starting their businesses. These findings are aligned with the literature supporting the importance of educational qualifications for MEs.

Another topic covered was MEs’ network in Madeira. 70 of the 96 MEs had family, relatives, or close friends living in Madeira. Of those 70, 21 had distant relatives, 25 had close family (parents, grandparents, siblings), and seven had all their family members living in Madeira before migrating. Another variable that captures the existing network in the host region is the membership of an association, group, or community of migrants on Madeira. Only 33.3 % (32) of our sample MEs said they belonged to such a network.

The areas of activity of MEs in Madeira are diverse but catering is the most relevant (22 %), followed by various areas of retail (20 %) and hairdressing (19 %). Notably, 27 % of the MEs have never been employed in Madeira, which is relevant to understanding their businesses’ importance. Regarding previous experience, around 24 % of the MEs in our sample had their own business before migrating to Madeira, mainly in the hairdressing and beauty sector. The MEs’ experience includes locksmithing, commerce, and tattoo artists. Some of this professional experience was acquired in Madeira, where migrants got their first jobs in restaurants, retail, hotels, hairdressing, and beauty salons. 12.5 % traveled to Madeira with a pre-agreed employment contract, while 6.3 % took less than a month to get a job, 6.3 % took between 1 and 3 months, and 12.5 % took between 3 and 6 months to get a job. However, 24 % took six months to a year, 6.3 % took between 1 and 2 years to get a job, and 5.2 % took more than two years to get their first job upon arriving in Madeira.

While starting their business, 48 % of the MEs took advantage of government subsidies or incentives, primarily for hiring personnel or to create their job. Of these 46 MEs, 27 believe these subsidies and incentives were sufficient to start their business. The remaining 19 believe this support was insufficient and, as described in the literature, needed informal financing (for example, loans from friends or family) or used their savings (mainly to maintain their business in the first months).

Finally, we also explored the importance of a “role model” in establishing a business. Most MEs (52 %) revealed they had a parent, family member, or close friend they consider a “role model”. Curiously, 70 % of those “role models” had their businesses in Madeira, while the remainder had businesses in their countries of origin.

Fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysisOpportunity-driven entrepreneurshipThe first analysis focused on the configurations leading to opportunity-driven entrepreneurship. FsQCA's intermediate solution yields five alternative configurations for the presence of OE (Table 3), thus confirming that alternative configurations lead to OE (Proposition 1).

Intermediate solution for the presence of OE.

Note: ● denotes the presence of the condition, and ○ represents the absence of the condition.

The literature describes opportunity-driven entrepreneurs as individuals who start their businesses based on identifying an opportunity to fulfill, for example, a desire for independence or a need for personal achievement. This decision generally does not depend on a negative context in the home country, as in configurations C1, C2, and C5. In these three configurations, the MEs do not identify significant problems in the home country (such as, for example, an unemployment situation – see Table 1 for details on the variables). However, such a negative context may occur (C4), and even if the MEs simultaneously find some barriers in the host country, they may end up starting a business classified as opportunity-driven entrepreneurship, considering the presence of KA.

Notably, the difficulties in the host country (for instance, excessive bureaucracy) and even the absence of KA or FS (C1 and C5, respectively) are not enough if the context in the home country is favorable. Alternatively, a positive context in the home country, combined with the presence of KA, can enable the presence of OE, even in the absence of IC (C2). Finally, C3 reveals the importance of Family Support (FS) combined with a perception of low barriers in the host country (BHC) to compensate for the absence of IC.

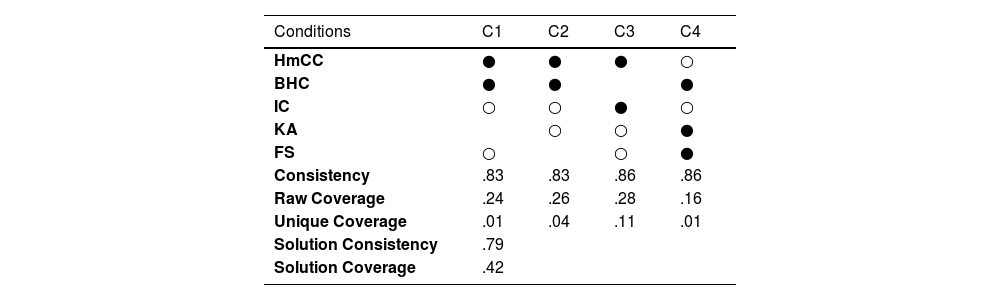

Absence of opportunity-driven entrepreneurshipIn this research, we posit that necessity-driven entrepreneurship, i.e., the absence of opportunity-driven entrepreneurship, is asymmetrical in terms of the configurations of conditions to the presence of opportunity-driven entrepreneurship, supporting the use of fsQCA as the data analysis instrument. This asymmetry is visible in the results presented in Table 4, which confirm that: 1) there are alternative configurations of conditions leading to necessity-driven entrepreneurship (supporting P1); and 2) these configurations are not symmetrical to the ones leading to the presence of opportunity-driven entrepreneurship.

Intermediate solution for the absence of OE.

Note: ● denotes the presence of the condition, and ○ represents the absence of the condition.

Despite the asymmetry of the solutions, it is evident that most configurations are well-aligned with the expectations of the negative context in the home country impact (C1, C2, and C3), pushing individuals towards necessity-driven entrepreneurship. In C1 and C2, this negative context is further aggravated by the perception of barriers in the host country, which, together with the absence of IC and FS (C1) or KA (C2), drive MEs to necessity entrepreneurship. However, alternatively, the presence of a negative context, even in the presence of IC, if KA and FS are absent, also leads to ∼OE (∼ represents the absence). Finally, there are cases where the context is not negative (∼HmCC), KA, and FS are present, but the absence of IC and the presence of BHC result in necessity-driven entrepreneurship.

Focusing on BHC, taking together the configurations for the presence (Table 3) and the absence (Table 4) of OE, it is clear that BHC is often present, revealing that: 1) this perception is shared by different types of individuals, despite their opportunity or necessity motivation to start a business, which could call for public policies; and 2) if the entrepreneur is targeting an opportunity, BHC won't be an unsurpassable barrier, for instance if KA is present.

Opportunity-driven entrepreneurship and formal government supportOne of the arguments presented in this manuscript points towards the benefits of migrant entrepreneurship in stimulating a region's development and facilitating the integration of migrants in the host region or country. In this context, it is unsurprising that some public policies may be enacted to take advantage of these and other benefits. Proposition 2 assumes that formal government support may facilitate entrepreneurship among the migrants, which would be especially relevant in terms of opportunity-driven entrepreneurship but not unimportant for necessity-driven entrepreneurship.

The results obtained for the presence of OE (Table 5) reveal an increase in the number of configurations, which is a direct consequence of including another condition in the analysis. Among those configurations, the prevalence of a positive perception of the role of the formal government towards opportunity-driven entrepreneurship is clear, but its absence is also pointed out. Nevertheless, the importance of GS becomes clear, thus supporting Proposition 2.

Intermediate solution for the presence of OE, including formal government support.

Note: ● denotes the presence of the condition, and ○ represents the absence of the condition.

In a more detailed approach, the same patterns as before are repeated, including the predominance of configurations in which HmCC is absent and where BHC is present. However, focusing on GS, although GS is absent in two configurations, it is present in most, revealing a positive contribution towards opportunity-driven entrepreneurship.

We ran a similar analysis for the absence of OE, implying the presence of necessity-driven entrepreneurship. We obtained a consistent solution revealing the same pattern regarding the role of GS, which is present in most configurations. Taking both the presence and the absence of OE, we find that despite most configurations revealing the presence of GS, there are several where GS is absent but not impeditive to starting a business.

Opportunity-driven entrepreneurship and previous entrepreneurial experienceThe literature stresses the importance of previous experience to the success of entrepreneurial decisions. Similarly to what we did with government support, we ran new analyses for the presence and the absence of OE, considering PEE as a new condition (Table 6). For the same reason, i.e., including a new condition, the analysis yields a higher number of configurations than the previous analysis (Table 3) where PEE is present or absent, thus revealing the importance of this condition for the presence of OE, therefore supporting Proposition 3.

Intermediate solution for the presence of OE, including previous entrepreneurial experience.

Note: ● denotes the presence of the condition, and ○ represents the absence of the condition.

A detailed analysis of the configurations in Table 6 reveals how PEE can have a differentiating role in enabling OE. Apart from the expected importance of HmCC and BHC, reinforcing previous configurations, and the presence of IC, KA, and FS, PEE is a complement to overcome existing challenges. It is evident that in the only configurations where PEE is absent (C4 and C7), KA is present (C4) to surpass the obstacles from the presence of HmCC and BHC, complemented by the presence FS in C7. PEE is present in all other configurations except for C1, which yields a “don't care” result.

Considering the best practices on fsQCA research, we also analyzed the solutions for the absence of OE. The results, not reported in this document, reveal the predominance of configurations where PEE is absent, which may reveal situations where individuals end up starting a business driven by necessity.

Gender effect on the modelOur research model also addresses the importance of gender in entrepreneurial outcomes, based on the assumption that, besides all other barriers, women may face additional challenges and may be pushed towards necessity-driven entrepreneurship. From this perspective, it was interesting to find that our sample has a balance between male and female respondents. To assess the importance of gender, we divided our sample according to gender to check if the configurations of the conditions are specific or not to a particular gender. The results for men are presented in Table 7a, and for women in Table 7b.

Intermediate solution for the presence of OE – male sub-sample.

| Conditions | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HmCC | ○ | ○ | ● | |

| BHC | ● | ● | ||

| IC | ○ | ○ | ||

| KA | ○ | ○ | ● | ● |

| FS | ● | |||

| Consistency | .82 | .87 | .79 | .80 |

| Raw Coverage | .32 | .36 | .32 | .27 |

| Unique Coverage | .07 | .12 | .11 | .07 |

| Solution Consistency | .80 | |||

| Solution Coverage | .72 | |||

Note: ● denotes the presence of the condition, and ○ represents the absence of the condition.

– Intermediate solution for the presence of OE – female sub-sample.

Note: ● denotes the presence of the condition, and ○ represents the absence of the condition.

Focusing on both solutions, we immediately notice that there are more configurations for female entrepreneurs than their male counterparts, signaling more complexity in the alternatives for women to become opportunity-driven entrepreneurs. Another interesting aspect relates to the fact that independent of gender, the absence of HmCC, the presence of BHC, and the absence of KA are configurations leading to the presence of OE (C2 for males and C1 for females), which is contrary to our research Proposition 4. However, we verify that the remaining configurations in both solutions are gender-specific, thus providing support to P4.

During the analysis of Tables 7a and 7b, we also verified specific differences, such as the importance of FS to female migrant entrepreneurs. Apart from C1 (similar to C2 for males), all configurations highlight the importance of FS, although, under specific conditions, this condition may be absent.

Regarding the absence of the outcome, i.e., necessity-driven entrepreneurship, the analysis for the males sub-sample did not yield a consistent solution, meaning that we could not find configurations that consistently associate with this type of entrepreneurship developed by males. However, we found three configurations for a consistent solution when focusing on females. These configurations, not reported in detail in this document, are characterized by the systematic absence of FS.

DiscussionThe research on migrant entrepreneurship addresses a relevant research gap (Mayuto et al., 2023), which is even more evident in the case of ultraperipheral regions. Taking advantage of the potential of fsQCA (still relatively uncommon in this specific field) to identify the configurations of conditions leading to opportunity- or necessity-driven entrepreneurship, our results reveal that, sustaining P1, there are different configurations of conditions (i.e., migrant entrepreneurship factors) leading to opportunity-driven and necessity-driven outcomes. Previous literature (e.g., Amorós et al., 2016; Calderon et al., 2016; Fairlie & Fossen, 2018) recognizes the differences between these two types of entrepreneurship, but considering that these different types of entrepreneurship are associated with differences in how businesses are run and their potential for success (Calderon et al., 2016) reinforces the importance of knowing the underlying factors leading to each type of entrepreneurship among MEs in an ultraperipheral region. Our results contribute to filling this research gap by revealing that there are several configurations of conditions leading to the presence of OE, but also several different configurations of conditions leading to the absence of OE (i.e., necessity-driven entrepreneurship), which are not symmetrical. This finding supports the complexity of the topic under analysis. It may be helpful, for instance, to support the design of public policies, as different characteristics of the ME may require different types of support and incentives to help move towards opportunity-driven entrepreneurship.

Focusing on the factors related to the home country (Brzozowski et al., 2014), we notice the importance of the drivers of migration, either because there are policies encouraging internationalization (Duan et al., 2021) or because the conditions in the home country are not favorable (Nkongolo-Bakenda & Chrysostome, 2019) – in the limit war (Chababi et al., 2017) – leading individuals to migrate. Overall, the results reveal that we can see a predominance of challenging contexts in the home country associated with necessity-driven entrepreneurship. In contrast, better conditions in the home country are predominantly associated with opportunity-driven entrepreneurship. However, this is not always the case, as there are configurations that state the opposite due to the interaction of this condition with others, and this is a valuable insight that is possible due to the use of fsQCA to analyze the data.

Aspects such as the institutional conditions in the host country (Lundberg & Rehnfors, 2018), the protection of entrepreneurs’ rights or bureaucracy (Chababi et al., 2017), or institutional support (Skandalis, 2014) influence entrepreneurship. However, several obstacles (Griffin-el & Olabisi, 2018) in the host country also impact entrepreneurship. In this field, most configurations in the opportunity-driven solution and all the configurations in the necessity-driven solution highlight the existence of barriers in the host region (Madeira). It is impossible to claim that these barriers impact the type of entrepreneurship. Still, future research could also address whether the barriers prevent other potential entrepreneurs from stepping forward.

The characteristics of MEs and their interaction with the conditions in the home and host countries help to understand the type of entrepreneurship. Unfamiliarity with the institutional and economic contexts in the host country (Campagnolo et al., 2022; Griffin-el & Olabisi, 2018) calls for the need to collect information, sometimes using the individuals’ personal network and other sources, and use previous management experience to take decisions on starting and managing a business. The results reveal that this factor is absent for most of the configurations under analysis, either for opportunity- or necessity-driven entrepreneurs, which may be considered a weakness for entrepreneurs migrating to Madeira.

MEs’ knowledge helps them overcome several barriers in the entrepreneurial process, either about the context in which they are developing their businesses (Lundberg & Rehnfors, 2018) or their educational levels (Chrysostome & Arcand, 2009). In this context, we may consider that MEs that score higher in knowledge acquisition will surpass the ones that score lower. However, the results obtained reveal a different reality. We found that opportunity- and necessity-driven MEs can reach their goal even in the absence of KA, which is peculiar. Considering the calibration decisions we made, this finding could mean that, from a certain level of knowledge, more knowledge does not contribute decisively to starting a business (however, considerations about differences in the performance level are beyond the scope and available data of this research).

Finally, still addressing P1, we focused on the importance of family support. This support may play a relevant role in several ways (e.g., Ljungkvist et al., 2023; Pruthi et al., 2018; Shinnar & Nayır, 2019), helping the MEs in their pursuit for success, either by granting access to information, or even financial support in the early stage of their businesses. Our results confirm the importance of family support but also reveal that even without such support, starting a business for opportunity or necessity is possible. However, the absence of family support is visible in more configurations for the absence of OE. In this specific context, it seems that the presence and absence of FS occur in the absence and presence of HmCC. This may lead us to question what kind of family support MEs may have when the conditions in the home country are problematic.

Including control variables in the analysis reveals the implications of formal government support, previous experience, and gender. Based on our analysis, there are different configurations of conditions leading to the absence and presence of OE in the ultraperipheral region under analysis, and those configurations are impacted by the control variables (P2, P3, and P4). This finding may be useful for academia, but we believe it is especially useful for practitioners and policymakers. For practitioners (i.e., MEs), our research shows that there isn't a single or ideal path toward starting a business, no matter if they are driven by opportunity or necessity. For policymakers, our research shows where public policies may be valuable, but at the same time, it becomes clear that some entrepreneurs are not getting the support that may help them succeed. Finally, our research explores the issue of whether women and men pursue the same type of entrepreneurship and how to design public policies enabling women and men to focus, to the same extent, on opportunities instead of addressing necessities. However, female migrant entrepreneurship is a topic with a certain level of complexity (Mindes & Lewin, 2024).

Conclusions, limitations, and future researchPrevious research highlights the importance of migrant entrepreneurship in improving migrants’ integration and living conditions, among other benefits. However, knowledge of migrant entrepreneurship in ultraperipheral areas, recently impacted by relevant migrant inflows, is scarce. Although generally more prone than natives to start a business, migrants face difficulties starting and running their businesses, aggravated by structural weaknesses in ultraperipheral regions. Furthermore, in the case of MEs in Madeira, the conditions in the migrants’ countries of origin may play a relevant role.

This research focuses on the factors influencing migrants while starting their businesses, including the home country context, their assessment of the barriers in the host country (in this case, considering the specific case of Madeira as an ultraperipheral region), as well as individual characteristics, knowledge acquisition, family support, government support, prior experience, and gender. Using fsQCA, we identify different configurations leading to opportunity- and necessity-driven entrepreneurship. This allows us to draw the first conclusion: different configurations lead to the same outcome (equifinality), either opportunity- or necessity-driven entrepreneurship. Furthermore, we confirm that the configurations for opportunity- and necessity-driven entrepreneurship are distinct and asymmetrical. Despite this dichotomy between necessity- and opportunity-driven entrepreneurship being natural – given the inherent characteristics of each type of entrepreneurship – using fsQCA highlighted some peculiar aspects that become very relevant for designing and calibrating public policies to promote migrant entrepreneurship.

As mentioned, our sample has a relevant base of MEs representing second- and third-generation emigrants from Madeira who have returned to their antecessors’ region. For these MEs, our findings imply that there is not only one path toward their objectives, enabling them to follow the path that better matches their pre-existing conditions. These facts, combined with the idea that most entrepreneurial projects are related to businesses closely linked to tourism (such as commerce and catering or essential services, especially in necessity-driven migrant entrepreneurship), which is very common in these ultraperipheral regions, allow us to conclude that education plays only a marginal role in promoting entrepreneurship for this target audience, suggesting the emphasis on technical or specialized training.

We also conclude that public policies play a crucial role in promoting funding availability for the projects’ development, and for opportunity-driven MEs these policies play an important role in promoting knowledge acquisition and family support (for instance, facilitating family reunification). These insights might be crucial for further developing and calibrating public policies in ultraperipheral regions to promote migrant entrepreneurship. Finally, differentiated public policies are critical when supporting male or female MEs. Opportunity-driven female MEs require more conditions to start their businesses, highlighting the importance of family support and knowledge acquisition while facing barriers in the host country.

The results obtained only involve MEs living in Madeira. Future work could extend the research to non-migrant entrepreneurs in this ultraperipheral region, studying the differences between the non-migrant and migrant populations. We also recognize the importance of using different sampling procedures and conducting the study in different ultraperipheral regions.

Another relevant limitation of this research is that we are only focusing on the MEs that succeeded in starting their business. We know little or nothing about others who, in a similar context, found that the existing barriers were too severe to handle. From the perspective of public policies, these MEs cannot be neglected, and we propose that new research addresses those potential MEs to whom, for instance, public support should be better directed.

Finally, we are aware that more sophisticated variants of fsQCA can, in the future, play a role in the analysis of the mediating conditions.

CRediT authorship contribution statementJosé António Porfírio: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. J. Augusto Felício: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Ricardo M. Rodrigues: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Tiago Carrilho: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Conceptualization.

The authors acknowledge the financial support from FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (Portugal), national funding through research grant UIDB/04521/2020. The authors also acknowledge the role of Nicole Olim Félix in data collection and conceptualization.