In the dynamic world of construction projects, fostering innovation is paramount. This study investigates the transformative potential of shared leadership as a catalyst for team innovation. We examine knowledge-sharing density as a critical mediator through the lens of knowledge management. We adopted a mixed methods approach, collecting multi-wave and multi-source field data and using social network measures. The results demonstrate shared leadership acts as a direct driver of knowledge-sharing density, facilitating innovation in construction projects. Knowledge-sharing density emerges as a transformative force, mediating the impact of shared leadership on team innovation. This intricate relationship unveils hidden potential for innovation within construction teams. Results also show the influence of team open-mindedness norms, which moderate the direct link between knowledge-sharing density and team innovation and the indirect influence of shared leadership. This study pioneers an integrated approach to understanding leadership and knowledge management in the construction sector, with important insights for team leadership, knowledge-sharing, and project performance.

Technological developments and increased competition have put construction organizations under pressure to produce innovative solutions (Leslie, 2022). Teams are indispensable to projects and are responsible for developing innovative solutions to sometimes unstructured and obscure technical problems (Shibani et al., 2020). Construction organizations aiming to focus on innovation promote teamwork and coordination among team members in a bid to diversify and blend strategies and solutions (Ali, Wang, Soomro et al., 2020; Laurent & Leicht, 2019). Teamwork, through collaboration, results in creative ways to innovate products, processes, strategies, and the organization as a whole (Li et al., 2015), ultimately leading to project success (Khan, 2024) and the overall performance of construction organizations (Ali, Wang, Soomro et al., 2020). Nevertheless, the success of team innovation is affected by the leadership and by members’ openness to sharing ideas, learning from each other, and to evaluating the ideas of fellow members.

Construction projects are complex time- and cost-bound ventures, and so are their project teams. While construction teams are initially formed at the start of a project, their composition often evolves over time due to factors such as job-switching, internal company movements, and project-specific demands (Olatunde et al., 2017). Construction teams are typically assembled for specific projects with finite timelines, requiring rapid multi-trade collaboration, coordination and adaptability among engineers, architects, and technicians (mechanical, electrical, plumbing, and IT, for example) (Dipin et al., 2023). Teams in many other industries differ in that they have long-term stability and operate within a relatively predictable environments (Khan et al., 2020). The fact that construction teams draw on people from across disciplines and functions adds complexity to coordination efforts. Another factor that can hinder smooth coordination, and ultimately innovation, is reluctance among team members to share their knowledge (Lin & Wang, 2019). This reluctance is mainly attributed to the short-term nature of projects and associated job security. In the construction industry, it takes years of work to become a skilled employee, and therefore the acquired knowledge is usually professionally sacred (Khan et al., 2020). Faced with job insecurity, construction employees may perceive sharing their hard-won knowledge in a team as jeopardizing their unique position or a value attributed to them (Khan et al., 2020). Knowledge-sharing hesitation among construction employees is evident when economic gains are at stake, such as in economically unstable regions or when there are few job vacancies in the market (Lin & Wang, 2019). While studies have emphasized the importance of knowledge-sharing for team innovation, there has been limited research into how leaders can mitigate these challenges, particularly in short-term construction teams facing dynamic membership changes (e.g., Rafique et al., 2022).

While the role of teamwork in innovation has intrigued researchers over the years, there are still no definitive and reliable conclusions about the relationships between known predictors and innovation (Ebersberger et al., 2021; Rafique et al., 2022). Our study aimed to demystify the relationship between team innovation and leadership. In today's organizations, leadership is rarely the role of a sole individual; rather, a collective form of administration (i.e., shared leadership) is often how teams are managed (Chiu et al., 2016). Shared leadership helps teams innovate by enabling conditions that raise members’ awareness of the problems, increase coordination, and guide them to openly share ideas and perspectives with fellow members (Ali, Wang, Soomro et al., 2020). There has been a significant gap in recent literature regarding an exploration of how hybrid leadership styles might foster innovation in temporary, multi-trade construction teams (Gan et al., 2024). Our study proposed that shared leadership––“a dynamic, interactive influence process among individuals in groups for which the objective is to lead one another to achieve group or organizational goals” (Pearce et al., 2007)––would foster team innovation by enabling knowledge-sharing and decision-making autonomy. We drew on the theory of team climate (Anderson & West, 1998) and integrated this concept with social network research to identify knowledge-sharing density as a mechanism that links shared leadership with team innovation.

Another area that has been under-explored is the boundary condition of shared leadership effectiveness when describing shared leadership as a predictor and knowledge-sharing density as a mechanism for team innovation (Alshwayat et al., 2021). Previous studies have noted that team norms are under-studied in innovation research in industries such as construction (Maynard et al., 2021; Tabassi et al., 2017). There is limited understanding of how team norms, such as open-mindedness, can enhance knowledge-sharing processes in diverse teams, as in construction projects (Peter et al., 2015). In a team consisting of members from diverse backgrounds and with diverse knowledge faced with a fear of losing their job at the end of the project, members may exhibit less willingness to share their knowledge and will be less accepting of the suggestions and ideas of other members (Lin & Wang, 2019). In this scenario, shared leadership may not generate positive effects on innovation. So, aiming to understand this knowledge-sharing dilemma in construction project teams, we proposed a key team norm––open-mindedness––to capture the extent to which team members openly considered alternative perspectives and questioned their own positions (Tjosvold & Sun, 2003). Open-mindedness, we suggested, might enhance the effectiveness of shared leadership for knowledge-sharing and innovation.

In summary, our study contributes to an understanding of shared leadership, knowledge management, and team innovation in the realm construction of projects. It answers the call to explore the interactive effects of innovation climates on innovation outcomes (Newman et al., 2019) We view shared leadership as a structure in contrast to hierarchical leadership that fosters collaboration, skill recognition, ideas exchange, and innovative problem-solving (Ali, Wang & Johnson, 2020). We proposed knowledge-sharing density as an interactive, team-level concept, indicating the extent of knowledge-sharing among team members. We also introduced open-mindedness norms as a potential moderator, explaining shared leadership's effectiveness in project teams. Fig. 1 shows the theoretical model we used for this study. Table 1 illustrates the definition of the model variables.

Research model variable.

| Model variable | Definition | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Shared leadership | Shared leadership is a leadership model in which decision-making and leadership responsibilities are distributed between multiple team members rather than centralized in a single leader. | (Ali, Wang, Soomro et al., 2020; Peter et al., 2015; Wu & Chen, 2018) |

| Knowledge-sharing density | Knowledge-sharing density refers to the extent and frequency of knowledge-exchange within a group or organization. It measures how actively and efficiently individuals share information, ideas, and expertise, contributing to overall organizational learning and innovation. | (Schouten & Felps, 2011)(Lin et al., 2015) |

| Team innovation | Team innovation refers to the process by which a group of individuals collaboratively generates and implements new ideas, solutions, or products. It involves creative thinking, problem-solving, and the integration of diverse perspectives to drive improvement and adaptation within the team or organization. | (Mitchell & Boyle, 2019; Zacher & Rosing, 2015) |

| Open-mindedness | Open-mindedness is the willingness to consider new ideas, perspectives, and experiences without prejudice or bias. It involves being receptive to differing viewpoints and being flexible in thinking, allowing for growth, learning, and better decision-making. | (Tjosvold & Poon, 1998) |

The role of teams in construction projects is essential for problem-solving and operational efficiency (Shibani et al., 2020). Research has highlighted the pivotal role of shared leadership in influencing team creativity and innovation performance (Chiu et al., 2016; Lyndon et al., 2020). While team members may not inherently possess innovative capabilities individually, collective efforts and knowledge-sharing drive team innovation synergistically (Jiang & Chen, 2018). Our study delved into the core mechanism of knowledge-sharing density as a vital link connecting shared leadership to team innovation. Drawing on team climate theory (Anderson & West, 1998) and factors such as vision, participative safety, task orientation, and support for innovation, we explored the intricate relationships among these components, shedding light on the nuanced dynamics shaping team innovation in a construction context.

Shared leadership and knowledge-sharing densityOur study was grounded in the work of Hansen et al. (2005), Khvatova et al. (2016), Lin et al. (2015), and Nirmala and Vemuri (2009). These studies considered knowledge-sharing as a network-oriented process. Knowledge resources inherently vary in their content and amount among team members (Choi et al., 2010). Answers to the questions “who needs which kind of knowledge?”, “who wants to share knowledge?’, and “who wants to share knowledge with whom?” have broad implications for team outcomes.

Our concept of knowledge-sharing density considered these points. According to network research (Han et al., 2020), knowledge-sharing density refers to how many members share knowledge with how many team members. A similar concept was also presented by Nirmala and Vemuri (2009) in their study of knowledge management. They argued that density could be a measure of knowledge-sharing. Each team member is a node in the knowledge-sharing density, and sharing density indicates how many nodes are connected to share knowledge, such that the more nodal connections, the higher the team's knowledge-sharing density.

Due to the network-oriented character of knowledge-sharing density, we posited that shared leadership would positively influence knowledge-sharing density in a project team. First, with shared leadership, members are aware of the knowledge and limitations of one domain of expertise (Kukenberger & D’Innocenzo, 2020), as the performance of individual members is measured collectively in terms of team performance (Sharifirad, 2014). Members, therefore, look collectively at team task problems, proactively exchange knowledge and support each other in resolving any issues that affect overall team performance (Ali et al., 2019).

Second, shared leadership develops team norms of appreciating other members’ knowledge and expertise while understanding one's own strengths and weaknesses (Wu & Chen, 2018). Through interactive shared leadership, team members have self-awareness and an awareness of other members’ unique knowledge, understanding the contributions of each team member in team tasks (Ali, Wang, Soomro et al., 2020). When a team is looking for innovative ideas, members are aware of who can help them and can better target their knowledge contributions to the members in need of knowledge. They are more willing, therefore, to seek and share knowledge effectively among team members (Cao & Ali, 2017). Based on these concepts, we proposed:

Hypothesis 1

Shared leadership will be positively related to team knowledge-sharing density in a construction project team.

Knowledge-sharing density and team innovationAccording to Schumpeter (1934), innovation is the result of integrating disconnected chunks of knowledge and recombining them into a novel product, process, procedure, concept, or practice that can bring value to the organization. How team members foster, develop, carry through, react to, and modify ideas directly relates to this process, leading to team innovation (Paulus et al., 2021). Therefore, team members’ interaction and knowledge-exchange play a critical role in increasing the relevant knowledge pool and divergent ideas. Our study proposed that knowledge-sharing density fostered by shared leadership would be related to team innovation. Shared leadership encourages knowledge-sharing by every team member (Ali, Wang & Johnson, 2020). This interaction between team members leads to a two-way knowledge-sharing process, in which all team members are encouraged to participate, bringing diverse knowledge, unique insights, and divergent viewpoints, facilitating the generation of creative ideas (Zhang et al., 2019). In this way, team knowledge-sharing density brings more knowledge, ideas, and perspective, broadens the scope of team skills, and provides fresh ideas and thoughts. It inspires team members to look for innovative solutions (Hu et al., 2018), promoting team innovation (Mitchell & Boyle, 2019). Therefore, we hypothesized:

Hypothesis 2

Team knowledge-sharing density will be positively related to team innovation in a construction project team.

The moderating role of open-mindedness normsThe above arguments highlight the proposition that shared leadership is positively related to knowledge-sharing density among team members, increasing team innovation. Although knowledge-sharing density has a positive effect on team performance, the effectiveness of knowledge-sharing might also depend on the level of open-mindedness of team members. We suggested that knowledge-sharing density might have a weaker influence on team innovation if members were hesitant to accept contrasting viewpoints. In this situation, open-mindedness would be a team norm that helped reduce this reluctance (Mitchell & Boyle, 2015). Open-mindedness as a team's collective norm indicates how members should respond to divergent ideas, perspectives, and opinions in a team, creating a perception among members that they can make suggestions and raise concerns without hesitation.

In teams with a high knowledge-sharing density, members receive diverse knowledge and become aware of different ideas and viewpoints (Khan et al., 2023). In a complex construction project, however, abundant knowledge, perspectives, and ideas is not in itself enough for team effectiveness (Hazzan et al., 2013). Successful completion of a construction project requires substantial knowledge input from experts in various fields, such as civil, electrical, mechanical and IT, along with specialized contractors and suppliers (Laurent & Leicht, 2019). Team members may have to rely heavily on other team members’ input to achieve practical solutions. In this scenario, we suggested that open-mindedness norms would increase the likelihood of team members taking advantage of the high knowledge-sharing density by drawing on the unique knowledge of different members. We posited that when knowledge-sharing density was high, and open-mindedness norms were healthy, construction team members would be likely to bring more knowledge into team discussions and would be less reluctant to share ideas with other members. Open-mindedness would encourage members to share their perspectives and with senior members and accept junior members’ divergent knowledge and ideas (Mitchell & Boyle, 2015), thereby enhancing team innovation.

In contrast, when knowledge density was high, but open-mindedness norms were weak, the response of team members to the knowledge of others was likely to be less positive. In a construction project team environment, even when members had access to each other's knowledge, the presence of weaker open-mindedness norms would make members reluctant to accept divergent ideas or to apply knowledge to team tasks. When team members felt uncomfortable in openly considering ideas from other team members and did not value the knowledge and competencies of each other, we posited there would be an increase in hostility and conflict, leading to a decrease in knowledge-sharing density and ultimately undermining team innovation. We hypothesized:

Hypothesis 3

Open-mindedness norms will moderate the positive effect of knowledge-sharing density on team innovation. Knowledge-sharing density will have a more positive impact on team innovation when a team has a strong open-mindedness norm, and the positive effect will be weaker when a construction team has weak open-mindedness norms.

Integrated modelIn the previous sections, we proposed that shared leadership would be positively related to knowledge-sharing density (H1), knowledge-sharing density would be positively associated with team innovation (H2), and open-mindedness norms would potentially strengthen the positive effect of knowledge-sharing density on team innovation (H3). The final hypothesis integrates these relationships in a framework based on the moderated mediation concept suggested by Hayes (2018) and Hayes and Rockwood (2019). We proposed an integrated framework in which open-mindedness norms would moderate the indirect effect of shared leadership on team innovation through knowledge-sharing density. When open-mindedness norms were strong, shared leadership would have a stronger indirect effect on team innovation through knowledge-sharing density. When open-mindedness norms were weak, shared leadership would have a weak indirect effect on team innovation through knowledge-sharing density. We hypothesized that:

H4

Open-mindedness norms will moderate the indirect relationship between shared leadership and team innovation via knowledge-sharing density. The indirect effect will be stronger when open-mindedness norms are strong, and the indirect relationship will be weaker when open-mindedness norms are weak.

MethodsResearch context and data collectionWe collected data from the construction industry in Pakistan. Pakistan is typical of developing nations, with economic uncertainty, a pool of highly skilled professionals and a booming construction sector. As noted earlier, economic uncertainties are a prime reason for construction professionals hesitating in sharing knowledge and for reduced openminded norms. The Pakistan construction industry therefore appeared as a potential laboratory for testing the proposed model. We collected data from three companies operating in major cities. These companies were engaged in construction projects, including bridges, multi-storey malls, hospitals, and industrial sites. The human resource management offices of the companies helped contact potential team-based respondents and explained the nature and goals of the study.

Data was collected from project design teams working on various medium- large-scale and industrial projects. Each sample team was engaged in a common function, such as project planning, structural design, HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning) design, project execution monitoring, and specialized industrial construction. Surveys were conducted over nine months in three phases. In the first phase, out of 591 distributed questionnaires, 503 team members responded to questions about shared leadership, including control variables and demographic characteristics of the individuals and teams (age, gender, education, team tenure, and team size). In the second phase, three months later, 475 respondents out of those 503 respondents rated team knowledge-sharing density. They also rated their perception of the open-mindedness norms of their team. Finally, three months later, 65 team leaders rated the innovation performance of their team. We removed inaccurate individual responses (those with the same response to all questions or no response in all related surveys) and those which were unsuitable for network analysis (teams with less than an 80% response). The final useable sample consisted of 439 members in 65 teams, and 65 team leaders. The overall response rate was 74%, but the team response rate remained at more than 80%, making it feasible to conduct network analysis (Sparrowe et al., 2001). Of the 439 team members, 61% were male, and 83% had at least a bachelor's degree. Among leaders, the majority (91%) were over 35, 94% were male, and all had at least a bachelor's degree.

MeasuresThe survey instrument was developed based on previously validated scales.

Shared leadership is social interaction-based leadership, measured using a network density approach. This approach has been commonly used in previous studies (Ali, Wang & Johnson, 2020; Chiu et al., 2016; Martin et al., 2018). We gave a name list of team members and asked each respondent to answer one question: “To what extent does your team rely on this individual for leadership?”, on a five-point Likert scale. We then divided the sum of responses by the total possible value of team members’ responses to get the shared leadership density value of the team (Sparrowe et al., 2001).

We conceptualized knowledge-sharing density as a network measure reflecting the extent to which team members shared knowledge with each other (Nirmala & Vemuri, 2009). We followed the guidance of network literature to measure knowledge-sharing density. We provided all team members with names and asked them to rate according to their perception: “To what extent do you receive knowledge from this individual to perform your team tasks?” on a five-point Likert scale. We assessed knowledge-sharing density by aggregating all responses and dividing the sum by the total possible responses (Carson et al., 2007; Sparrowe et al., 2001).

A three-item scale from Tjosvold and Poon (1998) was used to measure open-mindedness norms. This scale has been used by other scholars (e.g., Mitchell & Boyle, 2015). A sample item from the scale was: “The team believes that every member's idea should be considered open-mindedly.” A five-point Likert scale was used to record the responses. Cronbach's alpha for this measure was 0.93. We aggregated the individual responses of team members to generate team-level scores. To justify the aggregation of individual assessments and confirm the validity and reliability of aggregated values, we calculated the within-group agreement index (James et al., 1984) and inter-class correlation coefficients (ICC1 and ICC2) (Bliese, 1998). The higher values of rWG (0.83), ICC1 (0.12), and ICC2 (0.47) provided statistical support for the data aggregation of open-mindedness norms.

Team innovation was measured using a four-item scale adopted from Welbourne, Johnson and Erez (1998). This scale had also been validated by other studies (e.g., Zacher and Rosing (2015). Team leaders were asked: “On the following measures, how would you rate your team innovation compared with other teams performing similar functions? (1) Coming up with new ideas; (2) Working to implement new ideas; (3) Finding improved ways to do things, and (4) creating better processes and routines.” Leaders rated their team on a five-point Likert scale– with 1 = needs much improvement and 5 = excellent. Cronbach's alpha for this measure was calculated at 0.90.

Finally, we controlled for team size, team tenure, average member age, average education, and gender of the respondent. Previous research indicated that formal leadership was related to team innovation. We therefore controlled the effect of formal transformational leadership behavior using a five-item measure (Carless et al., 2000) rated by team members. Cronbach's alpha of this measure was 0.98. The reasonable value of 0.94 for rWG, 0.44 for ICC1, and 0.84 for ICC2 proved the appropriateness of the aggregation of individual responses to calculate team-level scores for transformation leadership. In a team, where tasks are interdependent, members have to share more knowledge and coordinate with each other (Ali et al., 2019). Considering the nature of knowledge-sharing density and team innovation, we therefore controlled the effect of task interdependence using a five-item scale adopted from Zhang et al. (2007). Cronbach's alpha (0.92), rWG (0.96), ICC1 (0.05), and ICC2 (0.26) were all higher than the threshold. So the reliability and suitability of data aggregation were confirmed.

Analysis and resultsDescriptive statisticsTable 2 shows the means, standard deviations, and correlations among all variables of the study. The correlation values reveal initial support for the hypothesized relationships. For example, Table 2 reveals that shared leadership is positively related to knowledge-sharing density (r = 0.38, p<.01), and knowledge-sharing density is positively associated with team innovation (r = 0.55, p<.01).

Descriptive statistics and correlations matrix.

| Variable | Mean | SD | CA | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 3.14 | 0.34 | – | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 2. Gender | 1.61 | 0.17 | – | 0.01 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 3. Education | 2.51 | 0.33 | – | −0.25* | −0.02 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 4. Team tenure | 2.66 | 0.96 | – | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 5. Team size | 6.75 | 1.59 | – | .28* | −0.03 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 6. Transformational leadership | 3.56 | 0.62 | 0.98 | −0.04 | 0.07 | −0.06 | −0.03 | 0.16 | 1.00 | |||||

| 7. Task interdependence | 3.04 | 0.25 | 0.92 | −0.16 | .282* | .25* | −0.04 | 0.04 | .26* | 1.00 | ||||

| 8. Shared leadership | 3.50 | 0.60 | – | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.10 | .29* | 0.10 | 1.00 | |||

| 9. Knowledge-sharing density | 4.04 | 0.57 | – | 0.05 | .25* | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.13 | .28* | .33** | .38** | 1.00 | ||

| 10. Open-mindedness norms | 3.04 | 0.45 | 0.93 | −0.10 | −0.11 | 0.15 | 0.07 | −0.09 | 0.22 | 0.22 | .28* | .27* | 1.00 | |

| 11. Team innovation | 3.02 | 0.81 | 0.90 | −0.14 | −0.04 | 0.11 | −0.07 | −0.02 | .38** | .25* | .48** | .55** | .43** | 1.00 |

Note: SE = standard deviation, CA = Cronbach's alpha, *p < 0.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001.

We used PROCESS macro-Model 14 in SPSS 23.0 to test all the hypotheses of this study. We chose SPSS Macro as it allows for detailed mediating and moderation analysis, while offering flexibility in testing complex relationships between variables. It also provides robust results for bootstrapping and estimating indirect effects, which were crucial for our study. Table 3 shows the results of the regression analysis. H1 predicted that shared leadership would be positively related to knowledge-sharing density. The results indicate that shared leadership significantly predicts the knowledge-sharing density of a team (β = 0.33, p<.01). H2 predicted that knowledge-sharing density would lead to team innovation. Results show that knowledge-sharing density is positively related to team innovation (β = 0.42, p<.001).

Regression analysis results.

| Outcome variable | Knowledge-sharing density | Outcome variable | Team innovation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | R2 | β | SE | t | R2 | ||

| Main effects | Main and moderating effects | ||||||||

| Shared leadership | 0.33 | 0.12 | 2.68** | 0.29 | Shared leadership | 0.21 | 0.09 | 2.43* | 0.62 |

| Knowledge-sharing density | 0.42 | 0.09 | 4.60*** | ||||||

| Open-mindedness norms | −0.06 | 0.11 | −0.60 | ||||||

| Interaction | 0.44 | 0.11 | 3.83*** | ||||||

| Controlled effects | Controlled effects | ||||||||

| Age | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.35 | Age | −0.13 | 0.08 | −1.56 | ||

| Gender | 0.15 | 0.12 | 1.26 | Gender | −0.16 | 0.08 | −1.96 | ||

| Education | −0.10 | 0.13 | −0.78 | Education | −0.02 | 0.09 | −0.23 | ||

| Team tenure | −0.02 | 0.12 | −0.18 | Team tenure | −0.03 | 0.08 | −0.38 | ||

| Team size | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.59 | Team size | −0.09 | 0.08 | −1.10 | ||

| Transformational leadership | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.71 | Transformational leadership | 0.21 | 0.09 | 2.31* | ||

| Task interdependence | 0.30 | 0.15 | 2.03* | Task interdependence | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.90 | ||

Note: SE = standard error, *p < 0.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001.

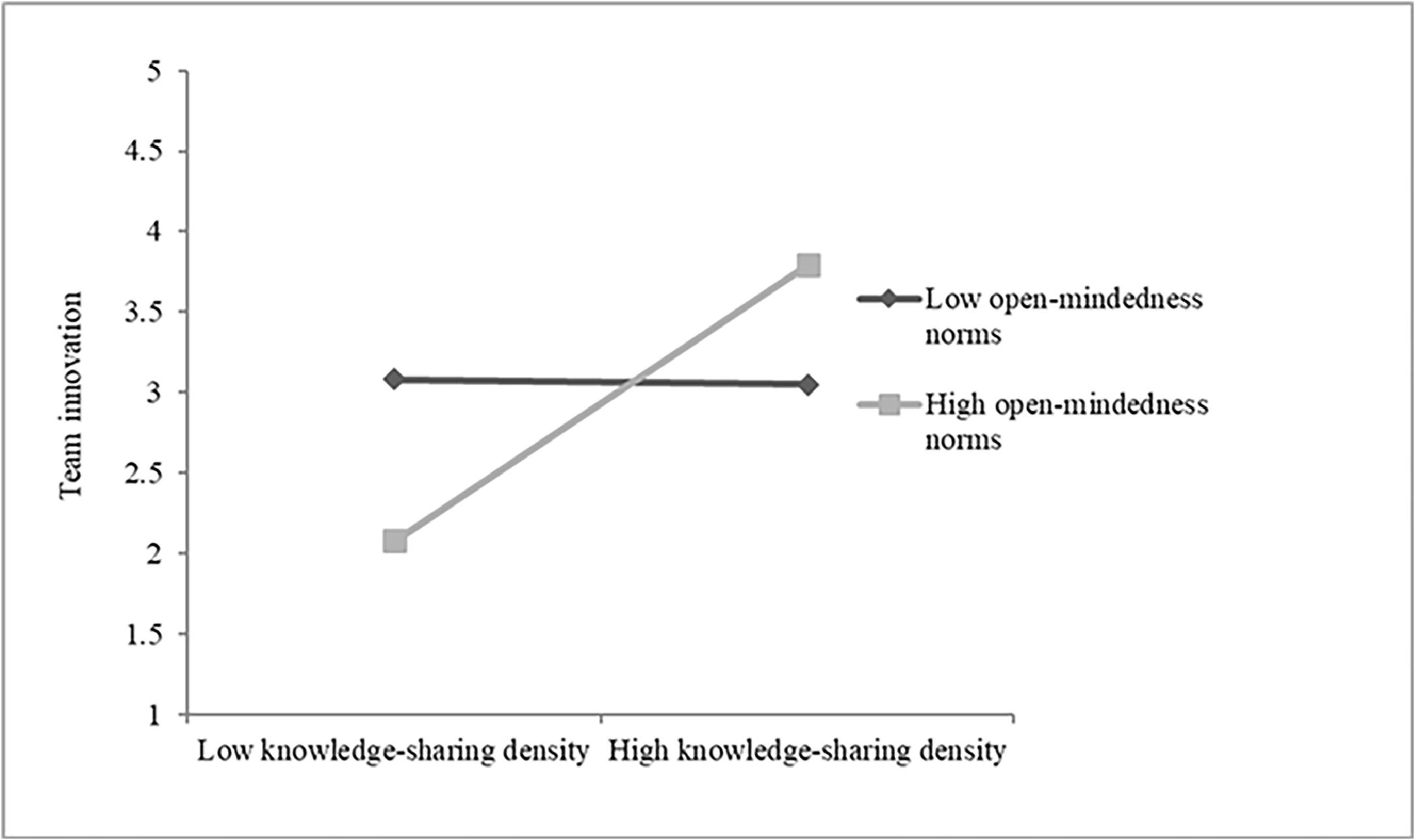

H3 suggested that open-mindedness norms would strengthen the positive relationship between knowledge-sharing density and team innovation. As shown in Table 3, the interaction effect is significant (β = 0.44, p<.001), thus supporting H3. To further explain the moderating effect, we followed the recommendations of Toothaker et al. (1994), and plotted the interaction effects at one standard deviation above and one standard deviation below the mean of the moderator. Fig. 2 indicates that, at a higher level of open-mindedness norms (one standard deviation above mean), the effect of knowledge-sharing density is stronger for team innovation (β = 0.82, p<.001). When open-mindedness norms are weak (one standard deviation below the mean), the effect of knowledge-sharing density is weaker (β = 0.07, pns).

H4 suggested an integrated moderated mediation model. Results of the moderated mediation analysis indicate that the indirect effect of shared leadership on team innovation was highest when open-mindedness norms were strongest at one standard deviation above mean (effect = 0.27, 95% CL [.0427, 0.5311]); when open-mindedness norms were less strong at mean (effect = 0.14, 95% CL [.0219, 0.2618]), and weak at one standard deviation below mean (effect = 0.02, 95% CL [−0.0896, 0.0764]). The index of moderated mediation (Index = 0.14, 95%CI [.0193, 0.3117]) also provided support for H4. The results collectively supported H4. The results of moderated mediation are presented in Table 4.

Conditional indirect effect of shared leadership on team innovation via knowledge-sharing density at values of open-mindedness norms.

| Independent variable | Mediating variable | Moderator | Effect | SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shared leadership | Knowledge-sharing density | Open-mindedness norms | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.0896 | 0.0764 |

| Shared leadership | Knowledge-sharing density | Open-mindedness norms | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.0219 | 0.2618 |

| Shared leadership | Knowledge-sharing density | Open-mindedness norms | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.0427 | 0.5311 |

Note: SE = standard error, CI = confidence intervals, LL = lower limit, UL = upper limit.

The findings of this study significantly expand current understanding of shared leadership and innovation in construction project teams, particularly in how they align or diverge from the findings of previous research. The positive impact of shared leadership on knowledge-sharing density aligns with recent studies (e.g., Imam & pH, 2021), who noted that shared leadership fosters collective engagement and problem-solving in project-based settings. The results underscore the pivotal role of shared leadership in enhancing team performance by facilitating communication between diverse, multidisciplinary team members, which is crucial in the construction industry where cross-functional collaboration is essential (Ali, Wang & Johnson, 2020). Our study, however, adds further nuance to the literature by identifying knowledge-sharing density as a critical mediator, a concept not sufficiently explored in prior research. Previous studies, such as those by Idrees, Xu, Haider and Tehseen (2023) and Imam (2021) touched on the importance of knowledge-sharing but failed to describe how the density of these exchanges directly influences team innovation. Our study fills this gap by demonstrating that high levels of knowledge-sharing density amplify the innovation potential of construction teams, especially in the context of short-term, project-driven environments. This echoes the findings of Rafique et al. (2022), who indicated that effective knowledge-sharing processes are integral to team innovation in dynamic industries, further cementing the value of shared leadership.

Our findings about the moderating role of open-mindedness norms also supports the findings of Mitchell and Boyle (2015), who suggested that open-mindedness fostered and strengthened an inclusive environment in which team members were more likely to share diverse knowledge, critical for generating innovative solutions. We found that when open-mindedness norms were weak, the team might experience stagnation or conflict, limiting the effectiveness of knowledge-sharing. This mirrors the conclusions of Wu and Chen (2018), who observed that the absence of open-mindedness diminished the potential of team-based innovation in complex projects like construction.

Our results contrast with earlier research by Tyssen et al. (2014), which suggested that leadership styles had limited influence in industries with temporary teams with complex tasks due to the transient nature of team composition. Our study demonstrated that shared leadership remained effective in these contexts, provided that the team climate was conducive, especially in terms of openness and willingness to share knowledge. Our study, therefore, offers a more optimistic view of leadership's potential to facilitate innovation in the construction sector, mainly when supported by a robust culture of open-mindedness and active knowledge-sharing.

Contributions to theoryOur study makes a significant contribution to the theoretical understanding of shared leadership, knowledge-sharing density, and team innovation, especially in the contexts of construction industry. First, it extends team climate theory (Anderson & West, 1998) by fit in the concept of knowledge-sharing density as an essential mediator between shared leadership and innovation. Previous applications of team climate theory have highlighted factors such as participative safety and support for innovation but failed to fully capture how dense knowledge networks within teams can amplify innovation outcomes, particularly in dynamic and short-term teams, as in the construction sector. Our study provides a more nuanced understanding of the impact of shared leadership on innovation through interpersonal knowledge-exchanges among team members, thereby enhancing the theory's explanatory power for complex, project-based environments.

Our study also contributes to the theoretical discourse on shared leadership by addressing a critical gap in understanding its applicability to temporary teams in construction projects. Prior research (e.g., Zhang et al., 2023), highlighted that shared leadership might be less effective in temporary teams due to changing team composition and time constraints. Our study challenges this view by demonstrating that shared leadership remains effective when supported by strong open-mindedness norms.

Our research also introduces a novel perspective by integrating social network theory (Borgatti & Halgin, 2011) with leadership and innovation research. While social network theory has previously explored knowledge-sharing behaviors, our study operationalizes knowledge-sharing density as a measure of network connectivity, linking it directly to team innovation outcomes. By situating shared leadership within a networked context, our study refines the theory of how leadership behaviors influence the density of knowledge-exchanges and how this density drives innovation, particularly in interdisciplinary teams.

Finally, our study enhances understanding of the role of team norms, particularly open-mindedness, as a moderating factor in the relationship between knowledge-sharing and innovation. While team norms have been studied in various organizational contexts, their role in mediating the effects of shared leadership on innovation has been underexplored, especially in the construction industry. Our research adds an essential layer to the theoretical frameworks, exploring the interaction between leadership style, team norms, and innovation by identifying that open-mindedness norms potentially strengthen the positive effects of knowledge-sharing density. Our results show that shared leadership, combined with a strong open-mindedness norm, actually encourages broader knowledge-exchange, breaking down potential silos and promoting innovation. This contribution is particularly relevant in interdisciplinary and project-based environments, in which open-mindedness can mitigate the challenges posed by transient team composition and can foster collaborative innovation.

Practical implicationsInnovation is crucial for construction organizations as a catalyst for increased project performance and for survival in the face of global competition. Construction industry literature highlights the need for project leadership structures that can be defined as an “engineering paradigm” to increase knowledge-sharing and collaboration in developing creative ideas for improving innovation (Ali, Wang, Soomro et al., 2020; Toor & George, 2008). Our study highlights the need for hybrid approaches to leadership when aiming for efficient construction projects. Informal shared leadership practices can help improve project leadership and project efficiency by increasing individuals’ involvement, collaboration, and commitment (Coun et al., 2018). Shared leadership creates a collaborative and proactive culture, resulting in increased knowledge-sharing and evaluation of ideas, ultimately leading to construction team innovation. Organizations should, therefore, aim to create an environment that encourages team members to step up and share leadership.

Our findings also highlight the significant contribution that shared leadership makes to facilitating knowledge-sharing density in project teams. This is especially important for construction projects because employee knowledge-sharing is critical for team innovation and project effectiveness. Construction projects involve complex and novel tasks that require extensive knowledge-sharing (Yin, 2006). Nevertheless, construction project teams tend to be short-term and to involve highly diverse professions, including project designers, architects, civil engineers, electrical engineers, and management executives. Due to these features, construction projects can lack knowledge-sharing and collaboration among employees, potentially limiting the possibility of innovation. Our findings suggest that sharing the leadership roles leads to team members feeling less vulnerable to losing their position in the organization and becoming more positive towards sharing knowledge with their peers. Recognition of the knowledge contributed by members, by virtue of shared leadership, also enhances knowledge interaction among the team members. More precisely, we found that knowledge-sharing density mediated the relationship between shared leadership and team innovation. We would therefore suggest that managers of construction projects create opportunities for employees to engage in leadership sharing, which encourages all employees to contribute their knowledge towards improving team innovation.

We also found that open-mindedness norms were important for promoting team innovation. In construction projects––where the scope of work is usually unique and beyond the boundaries of a single field of expertise––our results indicate that when members are open to ideas, suggestions, knowledge, perspectives, and criticism, the effect of knowledge-sharing density on team innovation was increased. An essential characteristic of open-mindedness norms is that these develop at an early stage of a project and are generally constant. The suggestion here, then, is that human resource managers consider open-mindedness norms in the recruitment process, and that project managers develop a culture of sharing ideas and knowledge with team members at the very start of the project.

ConclusionsThis study highlights the critical role of shared leadership, knowledge-sharing density, and open-mindedness norms in fostering team innovation within the construction industry. By integrating team climate theory with social network theory, our research provides a comprehensive framework that links leadership styles to knowledge-sharing dynamics and innovation outcomes. The findings highlight shared leadership as significantly enhancing knowledge-sharing density, which in turn drives innovation in project-based and interdisciplinary teams. The moderating role of open-mindedness norms is also shown to be essential in amplifying the effects of knowledge-sharing, suggesting that team climates conducive to open dialogue and mutual respect are necessary for maximizing the benefits of shared leadership.

However, this study is not without limitations. Our data was confined to construction teams in one developing country, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other industries or developed countries. Nevertheless, our model framework and results are likely to apply to any region with conditions similar to those of Pakistan––a developing economy with economic and market uncertainties but a booming construction industry. A second limitation is that the cross-sectional nature of the data reduces the ability to infer causality. While our study delves into the dynamics of shared leadership and knowledge-sharing density, it does not explore the potential effects of other leadership styles, such as transformational or transactional leadership, which could provide deeper insights into the conditions under which different leadership approaches are most effective in promoting innovation.

Future research should address these limitations by extending the study to diverse industries and developed regions to validate the generalizability of the findings. Longitudinal studies would also provide a more robust understanding of the temporal effects of shared leadership on knowledge-sharing and innovation. Exploring how other leadership styles interact with shared leadership, or even examining hybrid leadership models, could offer valuable insights into optimizing leadership structures for complex, project-based environments. Future research could also examine the role of digital communication tools and platforms in enhancing or impeding knowledge-sharing density, given the increasing reliance on technology in modern construction projects.

Data availability statementSome or all data, models, or codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethical approvalAll procedures performed in studies involving human participants were following the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Ethical approval was taken from the ethical committee of participating organizations.

FundingThere was no funding taken for this study.

CRediT authorship contribution statementMohsin Ali Soomro: Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Ahsan Ali: Software, Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Aftab Hameed Memon: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Shabir Hussain Khahro: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Methodology. Zubair Ahmed Memon: Writing – review & editing, Software, Resources, Project administration.

The authors are thankful to Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for paying article processing charges and scholarly support for this publication. Additional this study was also partially supported by research start-up grant by Zhejiang Sci-Tech University (11212932612215).