This study investigated the moderating effect of collectivism as a national culture on the interaction between organizational culture (measured in terms of clan, adhocracy, market, and hierarchy cultures) and commitment in the context of SMEs. A total of 1200 questionnaire surveys were delivered to 155 SMEs, of which 356 were deemed valid. The hypotheses were tested using a hierarchical multiple regression analysis. According to the findings of the study, a significantly positive relationship between organizational culture and commitment was discovered, and collectivism, as a national culture, moderates this relationship significantly. This study offers several recommendations for future research in this field. SMEs should prioritize the development of a better culture to generate a higher level of organizational commitment. Future scholars could use additional organizational contextual components as mediating or moderating variables to explore the association between organizational culture and commitment.

For decades, academics and anthropologists have strived to study various communities globally by focusing on culture (Hubner et al., 2022; Nadarajah et al., 2022; Petts et al., 2022). Nonetheless, they have recently identified a relationship between organizational culture, human behavior, and corporate financial performance (Peng & Zhang, 2022; Scaliza et al., 2022). Organizational culture develops through morals, norms, and values and is a major driving force of human behavior (Elsbach & Stigliani, 2018; Haider et al., 2022; Thelen & Formanchuk, 2022). Organizational culture defines and represents people's assumptions of a company's workforce and influences their behavior (Naqshbandi & Jasimuddin, 2022; Naveed et al., 2022; Senbeto et al., 2022). They further believe that it is a crucial component of the performance of any business organization. Although organizational culture is not the only component in creating business effectiveness, promoting culture is one of the most significant variables (Sareen & Pandey, 2022; Smith & Drudy, 2022). Organizational culture is strongly and positively correlated with employee organizational commitment of employees (Ng, 2022; Park & Doo, 2020; Sharma et al., 2021).

Cultural differences are considered one of the prime factors that may affect performance positively or negatively (Leal-Rodríguez et al., 2017; Naveed et al., 2022). Several previous researchers have considered cultural differences only at a single level only (Hofstede et al., 1990; Weber, 1996), and they have been more concerned with the implementation of organizational culture and corporate culture within the firm. Hofstede et al. (1990) discovered that organizations in distinct countries have different core values, norms, and beliefs, whereas organizations in the same country merely have different practices. According to Hofstede, national culture has little effect on organizational culture. Conversely, (Nippa & Reuer, 2019) discovered the impact of cultural differences on two levels: national and organizational culture. Their findings demonstrated that national culture disparities have a significant impact on efficiency and competitiveness and that organizational culture differences may be employed to predict satisfaction indicators. From their perspective, national culture has some influence on organizational culture, and medium enterprises (SMEs) in different countries develop various organizational cultures based on the country's culture.

Individualism/collectivism is a national cultural dimension that may influence organizational culture (Hofstede & Bond, 1984). Individualism and collectivism are important factors of national culture because the four dimensions of organizational culture–clan culture, adhocracy culture, market culture, and hierarchy culture (Schein, 1985)–are dependent on national culture. SMEs operating in different countries will adopt different kinds of organizational cultures, which will have different impacts on organizational commitment. We can obtain a decent insight into Pakistani culture's vital determinants in comparison to other cultural identities when examined through the prism of the 6-D model (Insights, 2021; Leal-Rodríguez et al., 2016). Several scholars have utilized collectivism as Pakistan's national culture of Pakistan (Abbas et al., 2020; De Clercq et al., 2022; Zahra et al., 2022) so we apply collectivism to Pakistani national culture. This study aims to fill this gap by examining the interaction of collectivism as a national culture with a permissive contextual element as a means of explaining organizational commitment in Pakistan's largely unexplored context.

As organizational culture incorporates organizational values and principles that influence employees’ management, management techniques, benefits and incentives, career plans, and various other features that may affect organizational commitment, several studies have investigated the interactions between organizational culture and other organizational dimensions, including corporate strategy, leadership style, job performance, innovation, and sexual harassment (Vijayasiri, 2008; Yarbrough et al., 2011). Given that it has been suggested that employees working in groups are more committed, satisfied, and capable of producing better performance, this research was conducted to confirm the relationship between organizational culture and organizational commitment in a collectivistic culture (Huff & Kelley, 2005). Therefore, academics contend that connecting organizational culture to organizational commitment yields better results than integrating an established consultative project-derived collectivistic culture model.

Much of the previous literature on organizational behavior investigated the relationship between organizational culture, organizational commitment, and employee performance and found mixed results, such as positive relationships between organizational behavior and organizational commitment (Naveed et al., 2022; Petts et al., 2022), organizational commitment and job performance (Redondo et al., 2021; Van Waeyenberg et al., 2022), no relationship between organizational commitment and job performance (Hendri, 2019), a weak relationship between organizational commitment and job performance (Shaw et al., 2003), and differences in the relationship between UAE nationals and guest workers. Organizational commitment is a driving factor that keeps personnel in a specific course of action (Liu et al., 2020). Consequently, dedicated personnel become more dynamic and hardworking, and businesses with committed personnel become highly productive (Almeida & Coelho, 2019). However, the association between organizational culture and commitment has not been adequately researched in the larger picture of national culture, nor has the moderating role of collectivistic culture on this association.

Aiming to fill this research gap, the outcomes of this study contribute to the theoretical and practical understanding of organizational behavior and provide empirical evidence that, under the premise that the relationship between organizational culture and organizational commitment is context-dependent, collectivistic culture not only has a direct impact on organizational commitment but also moderates it. This study specifically aimed to address the following research questions: (1) Do the values of organizational culture such as clan culture, adhocracy culture, market culture, hierarchy culture, and collectivism as a national culture (Schein, 1985) affect organizational commitment? (2) Does collectivism as a national culture (Hofstede & Bond, 1984) moderate the relationship between organizational culture and organizational commitment?

To achieve this objective, we developed a conceptual framework and analyzed our hypotheses using data from 356 SMEs operating in Pakistan to find empirical answers to these questions by applying hierarchical multiple regression in SPSS 23. The main reason for selecting this country is that Pakistan is in South Asia, where regional cultures, norms, and values appear to be very important and firms are liable to adopt such cultural activities. Moreover, Pakistan is a collectivist culturally oriented nation, where people have a profound relationship with one another through collectivist cultural behaviors that foster the development of strong relationships between individuals (Khan et al., 2024). According to a review of earlier research, most empirical research has used sample data from industrialized nations such as the EU (Isensee et al., 2020), and the findings indicate that organizational culture has a positive impact on organizational commitment (Petts et al., 2022). It is predicted that similar findings will be derived in Pakistan despite the dearth of research on developing and impoverished nations, particularly in the context of Pakistan, and their inadequate use as a focus group in international studies (Khan et al., 2024).

This study suggests that SMEs in collectivist societies ought to refrain from cultivating an adhocracy, a market, or bureaucratic culture. Furthermore, this study contributes to theoretical understanding in two ways. First, it theoretically examines the organizational culture framework proposed by Cameron and Quinn (2005) and establishes the significance of the indirect process of changing cultural values for assessing commitment. Despite extensive empirical and scientific research on organizational culture, innovation, and commitment, Pham et al. (2021) contend that little is known about these issues in the context of manufacturing SMEs. Second, this study presents a conceptual framework for the multidimensionality of culture, including organizational culture, culture, and commitment.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the literature review on organizational culture, organizational commitment, and collectivism with the development of hypotheses. Section 3 describes the research methodology, data sampling, and research framework. Section 4 presents the statistical outcomes, and Section 5 presents the discussion, conclusions, and recommendations.

Theoretical background and hypothesisKnowledge gapsSeveral academics from across the globe unanimously agree that an organization's ability to be successful depends on its employees' perceptions of its organizational culture (Cameron & Quinn, 2005). When defining culture, Schein (2010) used the concept of "group" to refer to all social entity sizes in any organizational culture study. Prior studies have demonstrated the significance of organizational commitment due to the various positive impacts that arise from its existence (Murray & Holmes, 2021). It is crucial to cultivate it among employees because committed workers will outperform, remain with the organization longer, become more devoted, and become more effective (Boukamcha, 2023). Considering that organizational commitment is connected to organizational competitiveness and profitability, it is acknowledged as an important topic, particularly in management organizations (Hanaysha, 2016). Organizational culture can be a predictor of financial success (Aboramadan et al., 2020) and benchmark for organizational performance (Naveed et al., 2022). Given the increasing relevance of the economy and the surge in emerging global corporations, it is crucial to investigate how they achieve impressive feats (Zhang & Tansuhaj, 2007).

Research on SMEs indicates that SME businesses are affected by organizational culture (Arabeche et al., 2022). The impact of organizational culture on SMEs has not received significant attention in the literature (Anning-Dorson, 2021). It is extremely difficult for SME to encourage employees to perform their best at work under these circumstances (Wahjoedi, 2021). Hence, an important goal for SME is to understand the components that maintain employee commitment (PHAM THI et al., 2021). Surprisingly, SME are concerned about employee commitment and job retention (Abraham et al., 2023). Currently, manufacturing companies address organizational commitment as a commercial issue rather than only a human resource management concern (Sarpong et al., 2021). According to Messner (2013), organizational culture is critical for every activity that takes place within a business. Numerous studies have concluded that organizational commitment and culture are positively correlated (Saura, 2021; Sigalat-Signes et al., 2020). Therefore, the outcomes of this study may be useful to SME organizations in their endeavors to establish stronger and better cultures that will enhance staff commitment and decrease attrition.

Because of economic development and the emergence of multinational corporations, SME in Pakistan face significant obstacles in their pursuit of success. SME manufacturing organizations encounter many difficulties motivating employees to give them all in this environment (Nohria et al., 2008). Manufacturing SMEs must exert additional efforts to develop an organizational culture that emphasizes the key traits of a participating organization, the leadership style of the organization, employee management, and organizational cohesion—the ability to unite the organization's members. The literature review states that manufacturing SMEs must establish a bureaucratic, hierarchical, market-oriented, and systematic culture aggressively.

Organizational cultureNumerous scholars have defined organizational culture in different ways, considering its roots in anthropology. Schein (1985) defined organizational culture as “a pattern of basic assumptions that a given group has invented, discovered, or developed in learning to cope with its problems of external adaptation and internal integration, and that have worked well enough to be considered valid, and therefore to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems” ’(p.4). Organizational culture is defined by Robbins and Judge (2012) as “a system of shared meaning held by members that distinguishes the organization from other organizations.” Schein (2010) intended to help the organization and its stakeholders understand its functioning and provide them with norms and values to act within the organization (Schein, 2010). Such values and beliefs can be found in terms of the different languages, rites, procedures, rituals, myths, and firm performance that each organization adopts to make itself unique than others (Schein, 1985). Organizational culture has a direct impact on organizational commitment (Antunes & Pinheiro, 2020), firm performance (Saleem et al., 2019), and indirectly affects firms’ financial profitability indirectly (Dwyer et al., 2003). Organizational culture can also be a source of competitive advantage for firms (Wang, 2019).

Although several scholars have used different approaches to analyze organizational culture, we followed the CV framework derived by Cameron and Quinn (2005), which is useful for our study. CV framework is derived empirically, we can demonstrate its construct validity operationally, and it can potentially integrate several dimension of organizational culture proposed by many other researchers (Quinn & Cameron, 1988). This model consists of 39 indicators of effectiveness that laterally differentiate between two major dimensions and are combined to establish four main clusters. The first dimension extricates the effectiveness criteria of stability, control, and order based on the criteria of strain flexibility, discretion, and vitality (Cameron & Quinn, 2005). The second dimension differentiates between effectiveness criteria that strain rivalry, differentiation, and external orientation and criteria that emphasize unity, integration, and internal orientation.

Altogether, four quadrants are created using these two dimensions and these four quadrants are clan, hierarchy, adhocracy, and market. Each quadrant reflects a specific set of effectiveness indicators that develop behavior among people in an organization, such as how people working in the organization value their performance (Cameron & Quinn, 2005). They defined the core values to be used to estimate organizations. Surprisingly, the excesses of each scale replicate a value that appears contrary to the value on the other side (i.e., stability vs. flexibility, external vs. internal); therefore, the core values included in each quadrant signify opposite values.

Organizational culture and organizational commitmentMany studies have focused on the significance of workforce commitment to an organization's performance has been the focus of many studies (Ng, 2022; Park & Doo, 2020; Sharma et al., 2021). Such achievements resulting from commitment may depend on the organizational culture. Considering this, organizational cultural levels can be divided into three categories: environmental, organizational, and individual. Organizational culture definitions include strategy, leadership in terms of financial support, organizational culture, and procedures for human resource management (Lingo, 2020). Organizational culture refers to everyday rituals and conventions that employees perceive and observe in their place of employment (Assoratgoon & Kantabutra, 2023). According to Robbins and Judge (2012), organizational culture is the set of employee beliefs, regulations, perspectives, and behaviors that are frequently adopted by every individual of the organization. Organizational culture may also be defined as the customary, consistent, established rules and beliefs that an organization or department within an organization generally conforms to (Kotter & Heskett, 2008). Saura (2021) proposed that organizational culture encourages individual members of an organization to be committed and motivated. Several empirical studies have revealed a strong correlation between cultural commitment (Redondo et al., 2021; Van Waeyenberg et al., 2022). The CVF model was initially proposed by Cameron and Quinn (2005), and is a frequently employed aspect of the organizational culture model. Cameron and Quinn identified four types of organizational culture in their framework: adhocracy, hierarchy, clans, and market culture.

Organizational commitment is not a unified and well-defined concept. In organizational psychology and behavior, organizational commitment is defined as an employee's psychological adhesion to the organization. Organizational commitment is defined as “the relative strength of an individual's identification with and involvement in an organization. Conceptually, it can be characterized by at least three factors: (a) a strong belief in and acceptance of the organization's goals and values, (b) a willingness to exert considerable effort on behalf of the organization, and (c) a strong desire to maintain membership in the organization" (Mowday et al., 2013; Mowday et al., 1979; Shim et al., 2015).

The first objective of this study was to investigate the correlation between organizational culture and organizational commitment. Organizational culture has a positive linear relationship with organizational commitment (Lok & Crawford, 1999; Moon, 2000; Sigalat-Signes et al., 2020). Although little empirical evidence has been found regarding the strong relationship between organizational culture and organizational commitment, organizational culture characteristics such as corporate norms, beliefs, and values have been proposed to be correlated with organizational commitment and performance (Acar, 2012; Saura, 2021). It is further suggested that a supportive work environment and common goals and missions (clan culture) could result in higher organizational commitment (Brewer, 1993). Evidence has been provided by previous researchers on the significance of clan culture in organizations. The findings indicate that components of clan culture such as cooperation, teamwork, and engagement positively affect commitment (Kim, 2014). Likewise, other scholars contend in their research that a significant level of engagement encourages cognitive ownership, and that a profound commitment to the organization and its goals increases efficiency (Yazici, 2011). Although a negative effect of clan culture has been established on organizational performance, the authors were unable to find any meaningful evidence of the relationship between clan culture and organizational performance (Zhang & Zhu, 2012). Conversely, several other researchers have presented evidence of a positive relationship between clan culture and organizational commitment (Carvalho et al., 2018; Kim, 2014; Xie et al., 2020). The literature mentioned above provides significant proof and solid evidence that a clan culture is strongly linked to commitment. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

- •

Hypothesis 1a: Higher the collaborative and supportive working environment provided to employees at workplace (clan culture), higher the likelihood that they will designate organizational commitment.

It is further proposed that job autonomy, self-governance, and independence in the workplace (adhocracy culture) improve organizational productivity, facilitate employee motivation for innovation and creativity, and enhance organizational performance (Daft, 2012; Hart, 1998), and empowerment given to employees at the workplace has a positive effect on organizational commitment (Brewer & Clippard, 2002; Wilson, 1999). Adhocracy cultures are externally focused on and distinguished by their high levels of creativity and ingenuity. Significant levels of risk-taking, dynamism, and uniqueness are associated with this cultural manifestation (Silva et al., 2018). Employees are encouraged to have a strong commitment to the organization and constantly explore innovative ideas given this culture. This type of organizational culture responds rapidly to changes. Autonomy exists regarding innovative ideas that are beneficial for stimulating growth. Furthermore, an excellent incentive program inspires employees and promotes their commitment (Silva et al., 2018). To encourage innovation and swift change, organizations in this culture have flexible control over workers. Positive information-disseminating attitudes and behaviors in an adhocracy culture motivate employees to retain their jobs (Lund, 2003). The literature mentioned above presents evidence and strong arguments in support of the association between adhocracy cultures and organizational commitment. Therefore, the following hypothesis was developed:

- •

Hypothesis 1b:Higher the self-governance and independence and job autonomy given to employees at workplace (adhocracy culture), higher the likelihood that they will designate organizational commitment.

Competition and motivation (market culture) positively impact organizational commitment. Previous studies found that employees with high motivation and working in a competitive environment are likely to show a higher level of organizational commitment. In particular, they are more actively involved in the organization, which has a positive effect on organizational effectiveness and performance (Crewson, 1997). Kingsley and Reed (1991) studied the impact of different managerial levels on the decision-making process in public- and private-sector organizations (Kingsley & Reed, 1991). They tried to conclude whether managerial-level differences determine decision-making processes, unlike several other studies that analyzed sectorial differences. As expected, top-level managers with a wider scope of interests and longer periods of responsibilities (Camisón-Haba et al., 2019; Messner, 2013) have a higher level of authority to participate in the decision-making process than middle- or lower-level managers. A positive relationship between organizational commitment and power-related variables was found when the hypotheses were tested using the power-based theory (Wilson, 1999). Based on the above discussion of market culture, the following hypotheses are proposed:

- •

Hypothesis 1c:Higher the competition and motivation given to employees at workplace (market culture), higher the likelihood that they will designate organizational commitment.

Although several researchers have conducted studies on sectorial differences at various corporate levels, little attention has been paid to comparing the differences in employees’ motivation and organizational commitment between different managerial levels (hierarchy culture). A hierarchical culture in an organization is defined as one in which there is an apparent chain of command. The rigorous chain of command governed by official guidelines and behaviors lends development to the distinctive structure and control (Cameron and Quinn, 2005). Hierarchical culture emphasizes job security, stability, consistency, and dependability. Employees working in hierarchical organizational cultures respect authority and positions, and comply with specified rules, guidelines, and policies. According to Cameron and Quinn (2005), the administrator is usually the coordinator and organizer, who is vigilant of the developments occurring in the organization. The need to formulate and standardize current models, procedures, and techniques consistent with emerging business environment tendencies is the inspiration for the modification of hierarchical culture (Cameron and Quinn, 2005).

Previous research on organizational culture has suggested that organizational commitment can be predicted by analyzing hierarchy culture (Alqudah et al., 2022). This is consistent with research by Irfan and Marzuki (2018), who proposed that employees who experience a strong hierarchical culture are more committed to the organization (Irfan & Marzuki, 2018). The outcomes further indicated a positive connection between positive attitudes, sense of ownership, and personnel commitment to the organization and organizational culture. Organizational commitment and culture are key variables for organizational success and employee performance (Lee et al., 2014). Moreover, hierarchical culture has been found to have a substantial positive impact on workers' commitment to work (Muller et al., 2005). Hutabarat (2015) reported similar results and concluded that organizational culture has significant effects on academic staff members' work motivation by bringing in conjunction all academic stakeholders (educators, students, employees, and administrators), allowing them to cooperate in improving knowledge resources and education, which ultimately boosts educational staff members’ job (Hutabarat, 2015). The literature and theories mentioned above provide substantiation and compelling reasons to support the assumption that adhocracy culture and organizational commitment are correlated. Hence, we formulated the following hypothesis:

- •

Hypothesis 1d:Higher the opportunities provided to managers to participate in decision making process in the organization (hierarchy culture), higher the likelihood that they will designate organizational commitment.

Highly collectivist individuals do not accept inequality and high levels of autonomy. All group members strive for and express their intentions to attain collective benefit, and they usually express their common intentions for those benefits. (Olson, 2009) stated that “individuals whose individual contributions are shared equally and are unnoticed among groups have little incentive to contribute, and as group size increases, an individual's feelings of dispensability also increase. Since increased individual effort produces an inconsequential gain that is shared equally among the group members, an individual will loaf to pursue personal goals, thus receiving both collective and personal goods”. As it is increasingly difficult to monitor individual efforts or actions with an increase in group size, decreased social consequences for low effort have been found (Leal-Rodríguez et al., 2015; Leal-Rodríguez et al., 2023).

The basic element of collectivism is the core assumption that groups are cohesive, and individuals are mutually obligated. Collectivist societies are joint societies with the characteristics of diffusion, mutual obligation, and communal expectations constructed on ascribed figures (Lu et al., 2021; Pian et al., 2019). Social units with joint fortune, common values, and common goals are centralized in these societies, and the individual or personal simply becomes a constituent of social, making the in-group a significant element of investigation (Ali et al., 2019; Triandis, 2018). Collectivist societies tend to live in groups, work together in coordination with each other, and have mutual aspirations, common long-term objectives, a broader range of norms and values, and group membership. Collectivism is a diverse concept that combines different kinds and levels of culturally distinct referent groups and people. Collectivism can be referred to as a broader range of attitudes, norms, values, and behaviors than individualism in this way (Triandis et al., 1995).

- •

Hypothesis 2: Organizational commitment tends to be lower in collectivistic national culture

Clan culture: People with high collectivism scores denial of discrimination and super autonomy. These individuals oppose acquiring status, want to be recognized, and outperform other people. Therefore, collectivist cultures are considered through heteronomy and contention (Triandis, 2018). We anticipate here that the ‘winner take all’ attitude of individualistic people usually focus more on equality of the clan culture and will encourage a negative view of family alignment. The values of accomplishment and power that have been theoretically and experientially related to individualism lie on the opposite side of the values and beliefs of generosity and universalism, which are considered the core of a clan culture (Tiessen, 1997).

People with higher scores on collectivism emphasize equality and justice and collectively consider all members of the organization to be the same (Gardner et al., 2009). Individualist people stress connectedness, interdependence, and common goals, and show themselves similar to others working in the group; nonetheless, they do not simply submit to authority (Triandis & Gelfand, 1998).

Hence, existing theory and research propose that:

- •

Hypothesis 3a:Moderating role of collectivism will strengthen the positive relationship between clan culture and organizational commitment

Adhocracy culture: As mentioned earlier, people with high scores on individualism wish to be distinct and unique from others in the working group and tend to be highly autonomous. Hence, equality is hassled in individualism, and it stresses autonomous individuals rather than members of a collective group (Triandis & Gelfand, 1998). Considering this scenario, we understand that this pattern generally resembles the risk-taking and innovative environments of an adhocracy culture (Cameron & Quinn, 2005). People come together continually to analyze and solve problems in this type of dynamic culture. If they can contribute to dissection, it does not matter at all to the originality of the members regarding where and how they come from in the organization. Thus, we expect that individualists tend to prefer an innovative yet identical atmosphere of adhocracy culture (Eisend et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2022).

Collectivist individuals are part of the in-group and are awarded that some members of the group are of a higher status than others (Triandis & Gelfand, 1998). We expect collectivists to be unhappy and uncomfortable with the uncertain, flexible, and equal environments of adhocracy culture (Eisend et al., 2016). The values of conformity, tradition, and security that have been connected to collectivism lie in obstructing the standards of motivation and inspiration (consonants that focus on autonomy, flexibility, and innovation and the characteristics of adhocracy culture). Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

- •

Hypothesis 3b:Moderating role of collectivism will weaken the positive relationship between adhocracy culture and organizational commitment

Market culture: Individualists attempt to be well organized and wish to attain status and outperform other members of the organization. Therefore, competition and autonomy are the main characteristics of individualists people (Triandis & Gelfand, 1998). This emphasis on inequality, injustice, and independence reflects the intensive attention paid to a highly efficient and competitive market culture. People are justified independently of their productivity, performance, and efficiency in a result-oriented organizational culture, and accountability is dominant (Cameron & Quinn, 2005). In contrast to individualists, collectivists are not expected to be goal-oriented, productive, competitive, or accountable. Triandis and Gelfand (1998) found that collectivists assign more importance to contention than to any other personality trait. Collectivism is found to be negatively related to distributive justice and is reliable with the performance-based dispersal of payments, as found in market culture (Frank et al., 2015). Hence, we expect collectivism to weaken the relationship between market culture and organizational commitment. We further expect collectivism to view inequality, focus on achievement, and independence negatively in a market culture. The values of generosity and universalism conflict with the achievement, power, and values found in the market culture (Schwartz, 1990). It is imperative to focus on the negative relationship between collectivism and power values. Achievement and collectivism are also negatively correlated with competition in working groups (Gardner et al., 2009). Therefore, by focusing on accountability, competition, and achievement, we assume that collectivism is negatively related to market culture and organizational commitment. Hence, we predict the following:

- •

Hypothesis 3c:Moderating role of collectivism will weaken the positive relationship between market culture and organizational commitment

Hierarchy culture: In a hierarchy culture, we assume that individualists may have adverse views of the prejudiced, organized, and control-laden hierarchy culture. The values of stimulation and motivation are linked with individualism and theoretically contrasted by the values of security, conformity, and tradition found in hierarchical cultures (Gardner et al., 2009). Consequently, we assume that individuals tend to focus on rules, standardized procedures, and policies based on a hierarchical culture, as the converse of the creativity and flexibility of their desired culture. By contrast, collectivist individuals who are part of the in-group are awarded that some members in the group are of higher status than others (Triandis & Gelfand, 1998). This inequality acceptance seems to be characteristic of multiple levels of hierarchy culture, where rules, regulations, and procedures and standardized accountability of members in the group are assessed with performance to provide them a ladder to grow in the organization that deserves (Cameron & Quinn, 2005). Consistent with Cameron and Quinn (2005), we expected collectivists to prefer structures and different levels of hierarchical culture. Hence, we propose the following hypotheses:

- •

Hypothesis 3d:Moderating role of collectivism will strengthen the positive relationship between hierarchical culture and organizational commitment

Participants: The data sample for this research was collected from SMEs operating in the manufacturing industry in Pakistan, using a survey questionnaire. We collected data on organizational culture, collectivism, and organizational commitment from entrepreneurs, managers, and employees. However, there is a lack of research on manufacturing SMEs. Previous studies concentrated on the effects of organizational culture on organizational performance in Romanian firms (Tidor et al., 2012), commitment and job satisfaction in the Brazilian banking sector (Carvalho et al., 2018), and overall quality management in Nigerian corporations (Eniola et al., 2019). To achieve the findings of this research, this study targeted manufacturing enterprises for inclusion in data collection and analysis. The data collection method reflects conventional operating standards. The associated cover letters with questionnaires described the overall research objective, guaranteed respondents’ absolute confidentiality, asserted their entirely voluntary participation, confirmed only researchers' access to their responses, and were convinced not to share individual-level data beyond the research panel. Respondents adequately explained their answers and were encouraged to respond to the questionnaire with utmost honesty, which may minimize potential bias (Spector, 2006). Finally, participants may opt out of the survey at any time.

A total of 1200 survey questionnaire were distributed to entrepreneurs, managers, and employees of 155 SMEs. Out of 1200 survey questionnaires, 356 were completed and returned, which is 30% feedback and a sufficient percentage to conduct this study. There were no missing values in the responses. As all returned survey questionnaires were completed, they were included in our study. Of the 356 participants, 142 (40%) were female and 214 (60%) were male. The age of the participants ranged from 23 to 58 years.

Construct measurementsOrganizational culture: Organizational culture was measured using Cameron and Quinn's (2005) organizational culture assessment instrument (OCAI), which is consistent with the study of (Gardner et al., 2009). After carefully reading the initial organizational profile of the participants, they administered the OCAI to check the manipulation and evaluate the usefulness of the organizational profile in communicating the features of the introduced culture. The OCAI in this study consists of 19 items that explain the four basic dimensions of organizational culture developed and identified by Cameron and Quinn (2005): clan culture, adhocracy culture, hierarchy culture, and market culture, explaining the dominant characteristics of participating organizations, organizational leadership style, employee management of employees, organizational cohesion which means bonding the members and organization together, strategic emphases that determine how organizational strategies are reflected, and the criteria of success that regulate how success is measured or identified in the organization and who is rewarded. The OCAI has been used in previous studies and is considered to be reliable (Caliskan & Zhu, 2019; Leal-Rodríguez et al., 2016).

Collectivism: The HV-IC scale developed by Triandis and Gelfand (1998) was adapted to measure collectivism. This scale consists of six items, with eight items per scale. The detailed questionnaire items are provided in Appendix 1. 5-point Likert-type scale was adopted to measure this variable, where 1 denotes “strongly disagree” and 5 indicates “strongly yes.”

| Constructs with Items and References |

|---|

| Organizational Culture (Cameron & Quinn, 2005) |

| Clan culture |

| My organization is a very personal place. It is like an extended family. People seem to share a lot of themselves |

| The head of my organization points is generally considered to be a mentor, sage or a father or mother |

| The glue that holds my organization together is loyalty and for a tradition. Commitment to this firm runs high |

| My organization emphasizes point human resources. High cohesion and morale in the firm are important |

| In my organization, people value and make use of one another's unique strengths and different abilities. |

| Adhocracy culture |

| My organization is a very dynamic and entrepreneurial place. People are willing to stick their necks out and take risks |

| The head of my organization is generally considered to be an entrepreneur, an innovator or a risk-taker |

| The glue that holds my organization together is a commitment to innovation and development. There is an emphasis on being first |

| My organization emphasizes growth and acquiring new resources. Readiness to meet new challenges is important |

| People have a clear idea of why and how to proceed throughout the process of change in my organization |

| Market culture |

| My organization is very production oriented. A major concern is with getting the job done without much personal involvement |

| The head of my organization is generally considered to be a producer, a technician or a hard driver |

| The glue that holds my organization together is the emphasis on tasks and goal accomplishment. Production orientation is commonly shared |

| My organization emphasizes competitive actions and achievement. Measurable goals are important |

| Hierarchy culture |

| My organization is a very formalized and structural place. Established procedures generally govern what people do |

| The head of my organization points is generally considered to be a coordinator, an organizer or an Administrator |

| The glue that holds my organization together is formal rules and policies. Maintaining a smooth-running institution is important here |

| My organization emphasizes permanence and stability. Efficient, smooth operations are important |

| People feel that most change is the result of pressures imposed from higher up in the organization |

| Collectivism (Triandis & Gelfand, 1998) |

| In times of conflict, I let other people win because I do not want to disagree with them |

| People should refer to parents, elders, teachers, and other authority figures for decisions and opinions. |

| I cooperate with others as much as possible. |

| I make careful decisions about my behavior so that I do not give my family a bad name |

| I do not get into arguments with others even though I disagree with them |

| Having collaborative relationships is beneficial to the welfare of a group |

| Organizational commitment (Crewson, 1997) |

| I am willing to put in a great deal of effort beyond that normally expected in order to help this organization be successful |

| I would accept almost any type of job assignment in order to keep working for this organization |

| I could just as well be working for a different organization as long as the type of work was similar |

| This organization really inspires the very best in me in the way of job performance |

| I am extremely glad that I chose this organization to work for over others I was considering at the time I joined |

| For me this is the best of all possible organizations for which to work |

Organizational Commitment: Organizational commitment is a summation variable of six diverse questions: Organizational identification (job involvement and pride), willingness to do extra work, and organizational loyalty (willingness to stay and work for a long time). These three factors of analysis are similar to Crewson's (1997) three operationalized components, strongly including acceptance of organizational objectives, values, and beliefs, wish to remain the affiliate of the organization, and willingness to work hard for the organization (p.507). Similarly, a multiple measure of organizational commitment (loyalty, eagerness to work, internalization, and organizational values) was developed based on the selection of seven questions used by the Federal Employees Attitude Survey (FEAS, 1979; Crewson, 1997).

Control Variables: Gender, age, and education of the participants were used as control variables for this study because these components are the key determinants that can influence employees’ commitment to the organization. Previous studies on human relations suggest that women show lower organizational commitment than men (Aranya et al., 1986), employees with higher age and extended tenure at the workplace tend to be highly psychologically attached to the organization and exhibit organizational commitment (Allen & Meyer, 1990), and employees with higher levels of education have higher organizational commitment (Bakan et al., 2011).

Data analysisData samples collected for this study were analyzed using SPSS 23.0, and hierarchical multi-regression analysis (de Jong, 1999) was applied to test our hypotheses. Because of various modern developments, such as confirmatory analysis, non-linear effects, and interaction effects, multiple regression employing SPSS is considered one of the most unique substitutes to prior conventional analytical techniques (Wang et al., 2020). Several empirical studies have conducted multiple regression analyses to investigate the moderating impact of incorporating primary and secondary data (Montoya, 2019). While various previous studies (Ringle et al., 2020) have adopted structural equation modeling (SEM) to evaluate the moderating effect between different variables, we presumed that hierarchical multiple regression employing SPSS is the preferred approach for this research to determine our observations following (Sungu et al., 2019) by examining the moderating impact of occupational commitment on organizational commitment and job performance. Furthermore, several scholars have used multiple regressions in their research on culture to examine the relationship between organizational culture and organizational performance (Zeb et al., 2021), organizational culture and employee knowledge (Alassaf et al., 2020), digital organizational culture and innovation (Zhen et al., 2021), and the relationship between organizational culture and educational innovations (Caliskan & Zhu, 2019, 2020).

A convergent validity test was performed to develop an estimation model for complete self-ratings, using factor analysis. Thereafter, a modification matrix was created to select the items from the variables. Most goodness-of-fit indices were above the predefined cutoff point, and none of the loadings were less than the minimum threshold. The outer loadings across all elements of all constructs were higher than the standard value of 0.50 (Bandalos & Finney, 2018; Mulaik, 2009). Reliability and validity tests were conducted. This was performed by selecting the optimal goodness-of-fit benchmark for the structural model fit. The potential to ascertain how far the framework fits into the variation structure of the sample is called goodness of fit. The CFA assessment and research framework suited the dataset compared with the quantitative measurement criteria. To assess the reliability of the observations, Cronbach's alpha coefficients were applied, and Pearson's correlations among all measures were used to test convergent validity. Such indices can offer stronger substantiation of construct reliability and validity. Cronbach's alpha level of satisfaction was greater than 0.50. Finally, AVE and CR confirmed the constructs’ reliability and validity based on their minimum thresholds.

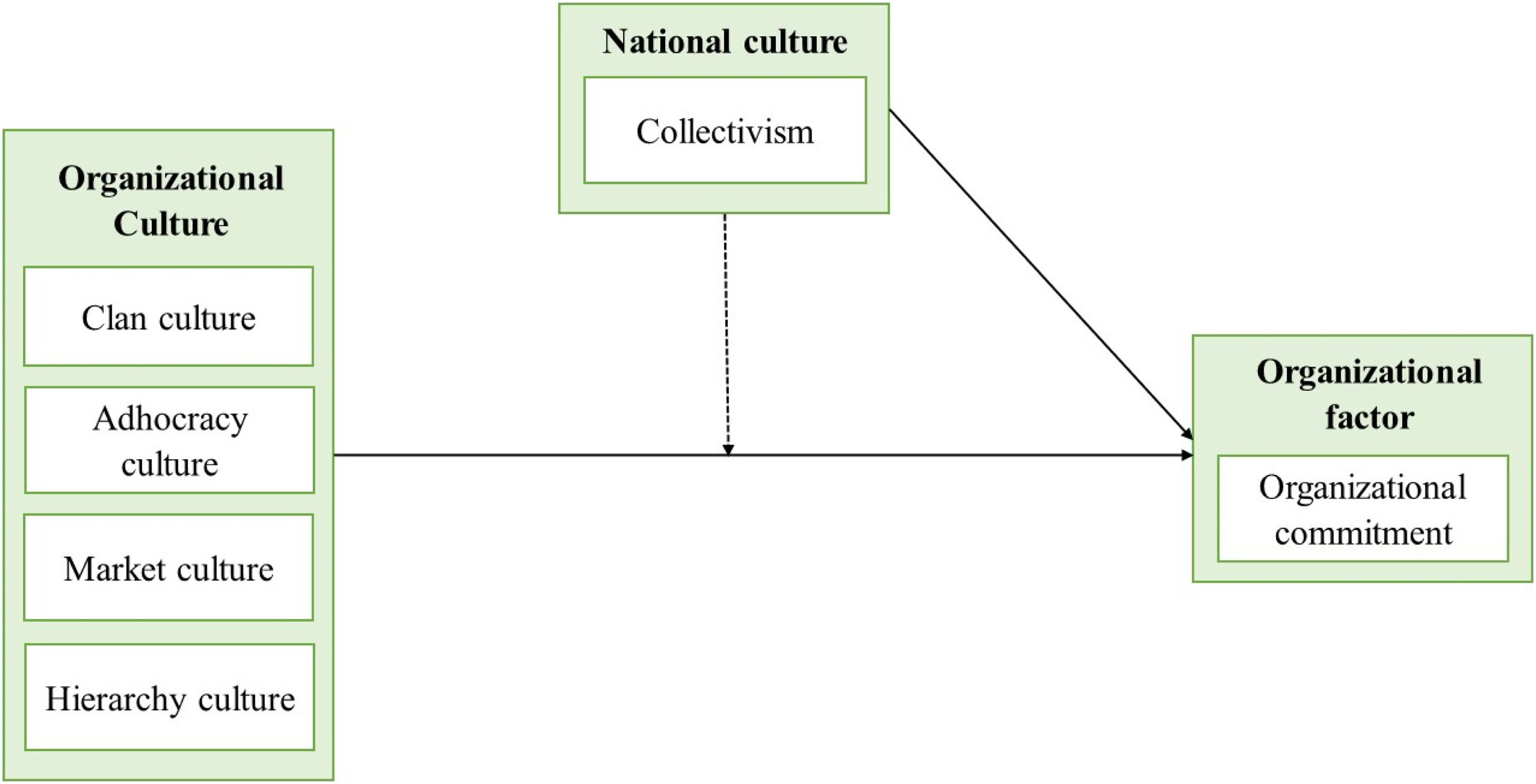

Fig. 1 shows our hypothesized research model in which clan culture, adhocracy culture, market culture, and hierarchy culture are regarded as independent variables, collectivism as the moderator, and organizational commitment as the dependent variable. Our research model shows that different types of organizational culture have a positive relationship with organizational commitment. Moreover, when collectivism is used as a moderator in the relationship between organizational culture and commitment, the relationship between the independent and dependent variables becomes stronger or weaker.

ResultsTable 1 shows that the cumulative KMO for all six indicators (clan, adhocracy, market, and hierarchical cultures as exogenous variables, collectivism as a moderator factor, and organizational commitment as an endogenous variable) is 0.768, which is higher than 0.001. This implies that the representative sample data used in this study are appropriate. Furthermore, the Chi-square estimate is 419.459 with a significance value of 0.000, which is acceptable.

Loadings, Bartlett Sphericity test, and KMO of items.

Common-method variance is an exaggerated variance that may be attributed disproportionately to the measuring technique compared to the presumed components that the measures are intended to represent (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The common method of variance was investigated using a previously proposed single-factor test (Harman, 1967). Although one component accounting for more than 50% of the total variation is thought to be indicative of common method bias, the results show that bias is unlikely to be a significant issue in these data. The first aspect, commitment, contributed to 35% of the overall variance.

Construct reliability and validityContent validity was used to assess the reliability of the CC, AC, MC, HC, COL, and OC scale. The standard Cronbach's alpha coefficients for the CC, AC, MC, HC, COL, and OC were 0.842, 0.845, 0.909, 0.889, 0.937, and 0.837, respectively. Since the components were examined on the same scales and correlations between components were employed, standard Cronbach's alpha coefficients were used to determine the sample's construct validity. We further performed the KMO's assessment of factor loading and Bartlett's sphericity of the analysis on the mean of the CC, AC, MC, HM, COL, and OC scales. Several of these parameters assist in determining the viability of content for factor analysis. For the factor analysis to be declared valid, the Bartlett test of sphericity must be substantial (X2 = 419.459, p < 0.01), and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin assessment of internal reliability can suggest beforehand if the data sample is large enough to reliably extract the components. We acknowledge the significance of Bartlett's test. Table 1 illustrates that the KMO ratings for CC was 0.733, 0.798 for AC, 0.765 for MC, 0.681 for HC, 0.794 for COL, and 0.634 for OC, where scores around 0.6 and 0.9 are excellent but values less than 0.5 are inappropriate.

Table 2 shows the reliability of all the factors included in the analysis. We performed reliability analysis to evaluate the reliability and validity of each component. Overall, Cronbach's alpha was 0.969 for a combination of 31 questions with a random sample of 356, indicating that all questions asked to evaluate all six components were reliable for this research. Furthermore, the outer loading for each factor was greater than 0.70. Various prior studies have validated elements with values greater than 0.5; hence, we included them as reliable elements. Factor loadings higher than 0.5 for each element indicate that all questions asked to respondents and utilized to evaluate variables were reliable and valid for this study. A discriminant validity analysis was performed to examine the extent to which the variables diverged. Internal consistency was indicated by composite reliability (CR). Composite reliability analysis showed that all components possessed values higher than the broadly agreed criterion of 0.7. To demonstrate construct validity, the element's AVE must be higher than the variance explained by the item and all the other elements in the research framework. This situation was created across all elements in this study, particularly the diagonal elements (AVEs) in Table 2, which were higher than those of the various components. In conclusion, the modeling analyses provided significant evidence for the reliability and validity of efficient implementation of the components.

Construct reliability and validity.

Note: AVE = Average variance extracted

Table 3 shows the correlation analysis derived from sample data of 356 entrepreneurs of SMEs operating in Pakistan in 2022 and shows that CMC, AC, MC, HC, COL, and OC are associated positively or negatively with each other, with the former being ubiquitous. The correlation results demonstrated that CC (r = 0.907, p < 0.01), AC (r = 0.240, p < 0.01), MC (r = 0.960, p < 0.01), HC (r = 0.902, p < 0.01), and COL (r = 0.884, p < 0.01) were significantly positively associated with OC. Additionally, as shown in Table 3, CC, AC, MC, HC, and COL were all positively correlated with each other.

Descriptive, correlations, mean, standard deviation, Cronbach's Alpha, CR, and AVE.

Note:⁎⁎,*statistically significant at the 1 and 5% levels, respectively; SD = Standard deviation

A simple multiple linear regression through the entry approach was applied to investigate the efficacy of CC, AC, MC, HC, and COL in determining the variance in OC. As recommended by (Tabachnick et al., 2007), all exogenous variables in the standard multiple linear regression framework enter the equation simultaneously, and are examined as if they entered the model after all other predictor variables. Moreover, each exogenous variable is evaluated based on its contribution to the reliance gap between the exogenous and endogenous variables (Tabachnick et al., 2007). The sequential multiple regression approach was avoided because of difficulties associated with this technique (Pallant, 2020), and concerns regarding this method, where the sequence of inputs is solely dependent. Preliminary investigations were conducted to ensure that the conditions of linearity, normality, multicollinearity, and homogeneity of variance were not compromised. With (F = 11.088, p < 0.000), the framework illustrates a 99.7 percent variance in organizational commitment. Table 3 shows that independent variables such as CC and HC are positively associated with OC, while AC, MC, and COL are statistically negatively associated with OC. Table 4 shows the exhaustive outcomes of the multiple linear regression analysis.

Hierarchical multiple regression analysis.

Note:**,*statistically significant at the 1 and 5% levels, respectively

Model 4 in Table 4 presents the moderating analysis findings. The outcomes indicate a direct significant association between CC and OC (β = 0.138, p < 0.01), AC and OC (β = 0.244, p < 0.01), MC and OC (β = 0.593, p < 0.01), HC and OC (β = 0.079, p < 0.01), and COL and OC (β = -0.780, p < 0.01), which significantly supports our proposed H1a, H1b, H1c, H1d, H2. Furthermore, we predicted that COL would act as a moderating factor between independent and dependent variables. The moderating interaction results (β = 0.079, p < 0.01), (β = 0.079, p < 0.01), and (β = 0.079, p < 0.01) provided in Table 4 show substantial evidence for H3b, H3c, and H3d support as contextual moderating interactions between AC and OC, MC and OC, HC, and OC, respectively. However, the outcomes (β = 0.079, p < 0.01) did not show any support for the moderating relationship between CC and OC; hence, H3a was not supported. The findings revealed a significant direct and indirect interaction between organizational culture and organizational commitment; national culture, for example, collectivism, serves as an important positive and negative significant moderating effect between AC, MC, HC, and OC, except for CC, which was not statistically supported.

DiscussionThis study investigates the relationship between organizational culture (as defined by clan, adhocracy, market, and hierarchical cultures) and organizational commitment in Pakistani manufacturing SMEs. Furthermore, this study explored the moderating significance of national culture, such as collectivism, on the relationship between organizational culture and commitment. The findings reveal that organizational culture has a significant positive association with organizational commitment, implying that culture is critical for sustaining personnel. These findings corroborate those indicated in the literature review by Acar (2012), who discovered a substantial association between organizational culture and commitment. According to Brewer and Clippard (2002), culture is a significant element in strengthening organizational commitment. Shim et al. (2015) discovered that managers who emphasize group culture are often committed to their workplaces. Messner (2013) similarly proposed a positive association between organizational culture and organizational commitment and encouraged the development of a corporate culture transformation approach to promote organizational commitment. Previous studies have offered sufficient evidence to determine the association between organizational culture and commitment. Consequently, corporations that intend to strengthen their personnel commitment must do everything to establish a strong organizational culture.

Descriptive statistical findings also reveal that national culture, such as collectivism, has a substantial impact on organizational commitment. This indicates that a national culture that is vigorously incorporated by every worker might provide efficiency and have a strong influence on other organizational members, notably minimizing the potential of personnel turnover. Consequently, organizational commitment is established. This suggests that to develop commitment among employees, each worker must implement a collectivistic culture with ideals ingrained in the organization daily. Numerous experts agree with the findings of the study, claiming that the greater the collectivist national culture, the stronger is the organizational commitment in personnel.

This study had three objectives. The goal was to theoretically examine the impact of changing organizational cultural values on employee organizational commitment. The results indicate that employees' organizational commitment may increase or decrease when exposed to variations in the values of organizational culture. The second objective was to examine how the national cultural context impacts the relationship between organizational culture and organizational commitment, such as collectivism. Pothukuchi et al. (2002) explained the relationship between national culture and organizational commitment along with suggestions for enhancing commitment in collectivistic cultures. This study observed a significant positive impact of collectivism as a national culture on organizational commitment among employees, which is consistent with the arguments of Pothukuchi et al. (2002). The third theoretical objective of this study is to contribute to the existing literature by incorporating national culture as a moderator. These findings provide empirical support for the contention that national culture strengthens the association between organizational culture and commitment when collectivism is included as a moderator.

ImplicationsManufacturing SMEs in Pakistan encounter serious challenges in gaining and maintaining success owing to financial challenges and the emergence of multinational enterprises. Obtaining personnel who perform quality jobs under such conditions is a serious issue for SMEs (Bokhari, 2022). SMEs must make special efforts to develop an appropriate organizational culture that emphasizes assistance, team cohesion, support, and providing a rapport working atmosphere, as well as asserting an innovative, productive, and engaging work atmosphere, eventually enhancing employee engagement to provide workers with plenty of responsibility to support them in complying with their everyday tasks (Al-Mamary & Alshallaqi, 2022). According to this investigation, SMEs in collectivist societies should avoid developing bureaucratic, adhocracy, or market cultures.

ContributionsThis study contributes to theoretical and practical endeavors. This study theoretically investigates the organizational culture framework proposed by Cameron and Quinn (2005), and establishes the significance of the indirect process of changing cultural values for assessing commitment. According to Xie et al. (2020), commitment levels do not grow primarily as an effect of organizational culture. They also emphasize how the engagement of society and culture strengthens the process that results from cultural values and commitment. According to Sharma et al. (2021), organizational culture establishes a broad basis for performance values and directs individual behavioral goals. According to Pham et al. (2021), there is a lack of research on organizational culture, innovation, and commitment in the context of manufacturing SMEs despite the significant amount of empirical and theoretical research on these issues. However, the most significant contribution of this study was the conceptual framework of the multidimensionality of culture that we presented, which included organizational culture, national culture, and organizational commitment. Together, these components have been the subject of multiple analyses in emerging contexts previously (Zeb et al., 2021; Zhen et al., 2021).

Furthermore, examining the interaction between cultural factors at the national and organizational levels contributes to scholars’ interest in empirical research that transcends levels of research (Anning-Dorson, 2021; Senbeto et al., 2022). According to Klein et al. (1999), two levels of analysis–individuals and organizations–are the main emphasis of multilevel organizational research (Klein et al., 1999). We fill this gap by extending theorists' perspective to include an additional field of study (national). Furthermore, this study conducts an empirical quantitative analysis of the differences in organizational culture dimensions across economies and connects them to their corresponding national cultural dimensions, while cross-cultural literature is typically rhetorical, descriptive, and qualitative in nature.

From a practical perspective, this study provides manufacturing SMEs with valuable recommendations regarding the significance of organizational culture in improving employee commitment and their subsequent performance contribution. Our research presents Pakistan's SME sector as a significant foundation for understanding the importance of cultural values as a cultivation tool for enhancing commitment to a collectivist culture. Organizational commitment is significantly affected by the presence of a productive environment characterized by adhocracy, hierarchy, markets, and clans, in addition to numerous other factors (Cameron & Quinn, 2005). A working environment characterized by a focus on customers, continuous development, focused goals, adventurous, versatile, business attitude, enthusiasm, job satisfaction, marketing-oriented decision-making, and rigorous norms is essential for the achievement of organizational objectives in different phases (Hogan & Coote, 2014). The findings also demonstrate how the manufacturing SME sector, which is typically difficult to approach in highly competitive environments, shifts in terms of perception through the adoption of a positive organizational culture and commitment to improve performance.

LimitationSince this study investigated the correlation between organizational culture and commitment in Pakistani SMEs, the findings may not be generalizable to SMEs across other countries, as organizational culture could be influenced by a nation's culture. All SMEs that agreed to participate in the survey agreed to a specified set of questions, with no specific proportion assigned to each organization. The researcher had difficulty obtaining a large number of elderly respondents, as most of them were between the ages of 20 and 35.

Recommendations and future researchBecause the researcher's significant contribution is to examine the connection between organizational culture and organizational commitment and the moderating role of collectivism in SMEs in Pakistan and because little concentration is given to this topic in the SMEs sector, the researchers concentrated on aspects beyond those adopted by different investigators in other relevant studies. SMEs must devote additional attention to these factors and implement them more effectively with staff. This may assist businesses in developing an appropriate culture and consequently achieving a maximum degree of commitment. Researchers have suggested that other organizational culture attributes, such as bureaucratic culture and employee empowerment culture, have an impact on organizational commitment, and that other contextual factors, such as job satisfaction, citizenship behavior, and leadership style, can mediate or moderate the association between organizational culture and organizational commitment.

ConclusionOne of the most important questions driving our study was whether respondents’ organizational attraction ratings would differ as a function of culture type. Our results show that different types of organizational culture (clan, adhocracy, market, and hierarchy culture) have a positive impact on employees’ organizational commitment. These results are consistent with those of previous studies (Lok & Crawford, 1999; Moon, 2000). Simultaneously, our study found that different national cultures can impact organizational culture and employee commitment. We argue that collectivism is Pakistan's national culture and has a strong impact on organizational culture. As discussed before, organizational culture is a kind of shadow over a country's culture, and our results can be explained in a explained by (Pothukuchi et al., 2002). We argue that the relationship between clan culture and organizational commitment will have a decreasing impact in individualist countries, but the same relationship will have a strong impact in collectivist countries. In other words, people from individualistic countries tend to show less organizational commitment and the other way around with collectivist nation people. Similarly, a positive relationship between adhocracy culture and organizational commitment in individualist countries will have an increasing moderating impact on whether collectivist nations will have a decreased moderating impact on the positive relationship between adhocracy culture and organizational commitment. Furthermore, employees in individualistic countries, such as the USA, Canada, the UK, France, and Australia, have relatively lower organizational commitment in the hierarchy than in collectivist countries (e.g., China, Japan, and Korea), where employee commitment is higher in a hierarchical culture. Finally, market culture having positive impact on organizational commitment, individualistic people tend to exercise more organizational commitment as compared to people from collectivist nations.

CRediT authorship contribution statementSyed Asad Abbas Bokhari: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Murad Ali: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Muhammad Zafar Yaqub: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Mohammad Asif Salam: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Data curation. Sang Young Park: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision.

This research work was funded by Institutional Fund Projects under grant No. (IFPIP:1226–120–1443). The authors gratefully acknowledge technical and financial support provided by the Ministry of Education and King Abdulaziz University, DSR, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

| Constructs with Items and References |

|---|

| Organizational Culture (Cameron & Quinn, 2005) |

| Clan culture |

| My organization is a very personal place. It is like an extended family. People seem to share a lot of themselves |

| The head of my organization points is generally considered to be a mentor, sage or a father or mother |

| The glue that holds my organization together is loyalty and for a tradition. Commitment to this firm runs high |

| My organization emphasizes point human resources. High cohesion and morale in the firm are important |

| In my organization, people value and make use of one another's unique strengths and different abilities. |

| Adhocracy culture |

| My organization is a very dynamic and entrepreneurial place. People are willing to stick their necks out and take risks |

| The head of my organization is generally considered to be an entrepreneur, an innovator or a risk-taker |

| The glue that holds my organization together is a commitment to innovation and development. There is an emphasis on being first |

| My organization emphasizes growth and acquiring new resources. Readiness to meet new challenges is important |

| People have a clear idea of why and how to proceed throughout the process of change in my organization |

| Market culture |

| My organization is very production oriented. A major concern is with getting the job done without much personal involvement |

| The head of my organization is generally considered to be a producer, a technician or a hard driver |

| The glue that holds my organization together is the emphasis on tasks and goal accomplishment. Production orientation is commonly shared |

| My organization emphasizes competitive actions and achievement. Measurable goals are important |

| Hierarchy culture |

| My organization is a very formalized and structural place. Established procedures generally govern what people do |

| The head of my organization points is generally considered to be a coordinator, an organizer or an Administrator |

| The glue that holds my organization together is formal rules and policies. Maintaining a smooth-running institution is important here |

| My organization emphasizes permanence and stability. Efficient, smooth operations are important |

| People feel that most change is the result of pressures imposed from higher up in the organization |

| Collectivism (Triandis & Gelfand, 1998) |

| In times of conflict, I let other people win because I do not want to disagree with them |

| People should refer to parents, elders, teachers, and other authority figures for decisions and opinions. |

| I cooperate with others as much as possible. |

| I make careful decisions about my behavior so that I do not give my family a bad name |

| I do not get into arguments with others even though I disagree with them |

| Having collaborative relationships is beneficial to the welfare of a group |

| Organizational commitment (Crewson, 1997) |

| I am willing to put in a great deal of effort beyond that normally expected in order to help this organization be successful |

| I would accept almost any type of job assignment in order to keep working for this organization |

| I could just as well be working for a different organization as long as the type of work was similar |

| This organization really inspires the very best in me in the way of job performance |

| I am extremely glad that I chose this organization to work for over others I was considering at the time I joined |

| For me this is the best of all possible organizations for which to work |