Customer relationship management (CRM) plays an increasingly crucial role in ensuring organizational performance, including marketing results (MR), in today's highly dynamic and competitive business environment. Simultaneously, CRM can be influenced by various factors involving innovations in all fields. However, the linkage between innovative work behavior and CRM, along with its impact on MR, remains an unexplored area of interest in the academic and business worlds. This research aimed to analyze the relationship between the two forms of innovative work behavior (IWB) (individual and organizational IWB) and the dimensions of CRM (customer orientation, CRM organization, knowledge management, and technology-based CRM), as well as the consequential MR. The data collected from employees in Romania were analyzed using structural equation modeling methodology. The main findings revealed that individual IWB (IIWB) does not influence CRM dimensions, while organizational IWB (OIWB) positively impacts CRM. In other words, the collective capability to create and implement new ideas, complemented by organizational cultures and managers that support team innovative behaviors, positively influences the development of CRM dimensions rather than generating and promoting new ideas at an individual level. Additionally, the study reconfirmed that most CRM dimensions are positively linked to good MR and play a mediating role in the relationship between OIWB and MR. The effects of these discoveries suggest that companies should emphasize fostering OIWB to improve CRM and enhance their competitiveness.

In the current, ever-changing economic, social, technological, and political environment, organizational innovation is crucial for business success. Innovative work behavior (IWB) relates to organizational innovation, which further contributes to increased business competitiveness (Jankelová et al., 2021), business sustainability (Thurlings et al., 2015), and customer satisfaction (Binsaeed et al., 2023). Simultaneously, customer relationship management (CRM) focuses on developing beneficial customer relations that improve customer satisfaction and add value to customers (Chalmeta, 2006). Because CRM fosters higher levels of customer satisfaction (Sin et al., 2005), its mechanisms are used for marketing activities that enhance relationships with customers (Binsaeed et al., 2023). Furthermore, innovative CRM has a dual effect: raising customer satisfaction and enhancing company performance (AlQershi et al., 2020). In this context, it is worth exploring how innovative work behaviors connect to CRM, as this relationship can support business competitiveness and performance through customer satisfaction.

Some scholars state that research on the relationships between innovative work behavior and organizational activities (Jankelová et al., 2021) on the one hand, and business performance (Maldonado-Guzmán et al., 2018) on the other, is limited. Although some studies have examined the consequences of IWB from human resources perspectives (Janssen, 2003; Kim & Koo, 2017) or on product innovation (Brătianu et al., 2023), to the best of our knowledge, no empirical studies have analyzed the impact of IWB on CRM. Therefore, the present study aimed to fill this research gap concerning the association between IWB and CRM. In this underexplored research area, only Rîpa and Nicolescu (2024) have attempted to explore the association between innovation and CRM based on companies’ discourse on their websites using a different methodology than the present one. Additionally, while numerous studies have analyzed the linkage between innovativeness and business performance at a general level (Jankelová et al., 2021; Nam et al., 2019; Racela, 2014), a few have focused solely on marketing results (MR) as a form of performance. For example, Brătianu et al. (2023) stated that there are limited studies on innovation process capability and customer knowledge level. Consequently, the present investigation aimed to address this research gap by examining the relationship between innovative work behavior and marketing results.

Thus, this study aimed to fill the aforementioned research gaps by examining the linkages among innovative work behavior, customer relationship management, and MR. Consequently, the study focused on the following two main research questions:

RQ1 How does innovative work behavior influence customer relationship management?

RQ2 How does customer relationship management influence marketing success?

Starting from these general research questions, the main objectives of this study were to (1) identify how the two forms of IWB (individual and organizational) influence the different components of CRM and (2) see how CRM relates to marketing results, measured based on consumer-related aspects.

To achieve these objectives and answer the research questions, a structural equation modeling (SEM) methodology was employed to identify and analyze the above relationships. The testing was based on data collected from employees working in organizations operating in Romania. The results indicate significant research contributions not only from theoretical perspectives—with the data proving the existence of linkages between organizational IWB and CRM components and further consequential marketing results, indicating a new valid model—but also from practical perspectives, as companies may use the results of this study to reinforce organizational IWB practices to foster innovative CRM practices and improve marketing performance.

The paper is organized as follows: the second section briefly presents the theoretical background on IWB and CRM, clarifying the related theories that support the design of the research model and the associated hypotheses. The third section includes detailed methodological considerations, while the fourth section displays the results of the analysis. The fifth section discusses the findings in relation to the literature, while the sixth and final section concludes the study by indicating theoretical and practical contributions, limitations, and directions for future research.

Literature review, conceptual framework, and hypotheses developmentThis section begins by describing how each of the three major areas of interest is presented in the literature: IWB with its two forms, the CRM with its four components, and, finally, the marketing results. This is followed by a discussion of the assumed relationships among these three theoretical topics of interest and the presentation of the conceptual framework, the linkages among the three areas of interest, and the associated hypotheses.

Innovative work behaviorAt a general level, IWB is seen as “the intentional generation, promotion, and realization of new ideas within a work role, work group, or organization, to benefit role performance, the group or the organization” (Janssen, 2003, p. 348). In an organization, IWB can be seen at both the individual and organizational levels, and both are important for encouraging innovations in all fields, including marketing and CRM, as well as for fostering organizational performance.

Individual IWB (IIWB) is defined as “encompassing a broad set of behaviors of employees, related to the generation of ideas, creating support for them, and helping their implementation” (Jong & Hartog, 2010, p. 23). IIWB has multiple dimensions related to the different stages of an innovation process, with Janssen (2000, p. 288) presenting IIWB as a complex behavior consisting of three different steps: idea generation, idea promotion, and idea realization. Additionally, Jong and Hartog (2010, p. 24) distinguished among idea exploration, idea generation, idea championing, and idea implementation as components of IIWB. IIWB models overlap, and the common elements were considered here.

Organizational IWB (OIWB) is assimilated to innovative business behavior that directly relates to the capability of groups of workers and employees to create and implement new ideas and solutions, simplify organizational processes, and improve organizational cooperation (Jankelová et al., 2021). Essentially, OIWB refers to team IWB (Hoch, 2013), which is influenced by both the organizational climate and culture (Jong & Hartog, 2007) and the team leaders’ behavior (Kmieciak, 2020). Therefore, an organizational culture and climate that supports creativity and innovation, along with trusting, encouraging, and knowledge-sharing leaders, as well as team IWB, are all part of the overall OIWB (Hoch, 2013; Kmieciak, 2020; Yuan & Woodman, 2010). In this study, both types of IWB—individual (employee level) and organizational (organization level)—were scrutinized.

Customer relationship managementCRM has been defined in different ways by different authors, most of whom have centered their definitions around the customer. Early on, Swift (2001, p. 12) defined CRM as “an enterprise approach to understanding and influencing customer behavior through meaningful communication in order to improve customer acquisition, customer retention, customer loyalty, and customer profitability.” Since then, the concept of CRM has evolved, incorporating integrated processes and technology-related solutions alongside customer-oriented purposes. For instance, some authors have emphasized the importance of integrating CRM across departments, viewing it as a cross-functional strategic activity aimed at developing relationships with customers (Frow & Payne, 2009), whereas others have highlighted the strong collaboration among all customer-facing functions, such as people, processes, and technologies (Goldenberg, 2015). Later, Srivastava et al. (2019) referred to CRM as an aggregation of strategies and processes that use appropriate software to build a customer-centric business aimed at satisfying customers. In recent years, authors have begun to consider the role of technology in CRM, defining it as “an activity that involves collecting, managing, and intelligently using data with the support of technology solutions to develop long-term customer relationships and exceptional customer experience” (Ledro et al., 2022, p. 48).

A vast body of literature illustrates that CRM is composed of numerous dimensions. Rîpa and Nicolescu (2023) presented a synthesis of the dimensions of CRM included in various models. The present study analyzed CRM using the model proposed by Sin et al. (2005), which considers four major CRM dimensions: key customer focus, CRM organization (CRMO), knowledge management (KM), and technology-based CRM (TCRM).

Sin et al.’s (2005) CRM model further details the four major dimensions of CRM with several facets for each dimension, offering a comprehensive description of the CRM concept. The key customer focus dimension refers to the company's focus on key customers to personalize offers for these strategically important customers (Ryals & Knox, 2001). The second dimension, CRMO, refers to how CRM is implemented at all organizational levels by fostering a proper internal working environment (Sofi et al., 2020). The third dimension, KM, refers to the learnings that an organization accumulates via experience and studies (Sin et al., 2005). Finally, the fourth dimension, TCRM, refers to the use of IT infrastructure and applications to interact with customers and build strong relationships with them, which includes data mining related to customer data (Soltani et al., 2018) and automated processes in marketing, sales, and customer service (Hanaysha & Al-Shaikh, 2022) that allow for new ways to relate to customers. Table 1 presents a synthetic overview of all facets for each of the four CRM dimensions.

Dimensions of CRM and their facets.

Source: Sin et al. (2005, pp. 1267–69)

Good marketing results can be seen as a form of organizational performance, a goal that all companies strive to achieve. Organizational performance is multidimensional, and various models have been developed to measure it (Guerola-Navarro et al., 2021). For example, Bryant et al. (2004) used a global model of performance that includes four perspectives: growth, business processes, customers, and financial perspectives. Others have proposed measures such as product or service quality; the success of new products, sales, and customer retention (Nakata et al., 2008); or profits, sales growth from customers, and long-term employment (Jankelová et al., 2021). Notably, all performance models also include aspects related to customers. Because the present study involved CRM, an activity highly related to customers, it focused on evaluating MR that refer to consumers—in other words, MR as a consequence of CRM that envisage building long-term relationships with customers. Given that marketing success is associated with customer satisfaction, customer loyalty, and customer retention as part of the company's performance (Herman et al., 2021), marketing results can be measured as customer trust, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty (Khanh et al., 2021). Other authors have also identified customer-related measures as suitable for measuring marketing performance and results. For example, Ambler and Kokkinaki (2000) identified six categories of performance measurement in marketing, two of which directly address the consumer: (1) consumer behavior in terms of loyalty and their gains, losses, and churn behavior and (2) consumer feelings in terms of satisfaction, commitment, and buying intention. Gao (2010) identified financial and non-financial measures for marketing performance, including customer satisfaction, customer loyalty, retention, and customer lifetime value among the non-financial measures. Recently, Morgan et al. (2022), who analyzed a variety of studies on measurements for marketing performance, found that numerous authors identified marketing metrics related to customers, including customer mindset metrics (such as advertising awareness and brand consideration), customer satisfaction, customer loyalty, customer equity, and customer orientation.

The present study used a similar method of measuring marketing results by looking at the image and prestige of the company, customers’ trust, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty.

Conceptual framework and hypotheses developmentThe relationship between IIWB and the CRM of a companyThe present research aimed to test a type of influence that has not been tested before: the influence of IIWB on the different facets of CRM, as seen in Sin et al. (2005).

Employees who are inclined to generate new ideas, promote their new ideas, and support the implementation of their new ideas (by manifesting their IIWB) contribute to higher levels of innovation in their organizations (Jankelová et al., 2021) in all fields of activity. Based on the generation and realization of new ideas from creative employees, innovations that occur in organizations include CRM-related innovations. The present study assumed that IIWB has a favorable impact on all CRM dimensions and formulated the first four hypotheses, one for each dimension of CRM.

Employees have innovative ideas and develop initiatives that, among others, can contribute to the development of new perspectives on customer experience (Brătianu et al., 2023; Mura et al., 2013) and improved collaborations with customers (Jankelová et al., 2021). Innovative employee capabilities and behaviors, and their entrepreneurial mindset, foster innovation for products specifically designed for key customers (Hock-Doepgen et al., 2024). Based on the generation and realization of new ideas from creative employees, innovations that occur in organizations include CRM-related innovations such as new approaches to customer communication (Vandermerwe, 2004), integration of customer engagement (Binsaeed et al., 2023), and customer involvement with the brand at a higher level (Rostamzadeh et al., 2024). As a result, customers are encouraged to generate and share their own content about the brand, fostering self-actualization (Ciunova-Shuleska et al., 2024). Employees’ IWB sustains a higher level of customer orientation via new proposals of interactive co-creation marketing. Based on the above, the authors posited the following:

H1 IIWB positively influences the customer orientation (CO) of a company.

Innovative behaviors of employees in the workplace, as a prerequisite for conducting innovation-related activities within organizations and for organizational innovativeness (Hock-Doepgen et al., 2024), can relate to the development of new business processes (Prajoho & Ahmed, 2006; Özel & Akgün, 2023) or simplifying existing processes (Jankelová et al., 2021). Moreover, they can contribute to designing new and improved operations that facilitate communication about customers across all departments (Mohammad et al., 2013), thus improving CRM organization. The innovation capability of employees (Janssen, 2000) and their innovativeness have a positive relationship with business model innovations (Hock-Doepgen et al., 2024) and business processes in general, including CRM processes in particular. This may include creating new innovative CRM procedures, introducing new processes (Özel & Akgün, 2023), developing novel activities (Hock-Doepgen et al., 2024), and adapting and improving existing CRM procedures (Kim & Wang, 2019) and organization of CRM activities at the company level. Consequently, the following relationship was assumed:

H2 IIW positively influences the CRMO of a company.

IIWB relates to the capability of employees to create and apply new ideas and solutions in practice (Janssen, 2000, 2003) across various aspects of a company, including CRM. In this context, the new courses of action proposed by employees may include more advanced mechanisms for customer knowledge gathering, dissemination, and use (Brătianu et al., 2023), as well as modern systems for utilizing social networks as platforms for information and knowledge collection and dissemination, particularly for younger customers who prefer the virtual world (Rostamzadeh et al., 2024). Additionally, leveraging the knowledge possessed by employees and introducing their novel and useful ideas for improving methods of gathering data on customer experiences or creating collaborative dialogues with customers (Gamage et al., 2021) represent forms of enhanced KM as a component of CRM. Accordingly, the authors speculated the following:

H3 IIWB positively influences CRM knowledge management within a company.

Employees’ IWB supports the innovation capability of an organization (Sanz-Valle & Jiménez-Jiménez, 2018), and technology is seen as one of the crucial pillars for addressing innovation challenges in CRM (Guerola-Navarro et al., 2021). This further allows companies to adapt to dynamic environments and remain competitive (Solberg et al., 2020; Halawa et al., 2023). The propensity of employees to propose and adopt new technology in customer relationships (Ledro et al., 2022) and develop new ways to monitor and track customer interactions (Afaq et al., 2023) are how IIWB contributes to the development of CRM based on the integration of new technologies, especially IT. For example, implementing proposals for the successful integration of modern technology, such as social media in CRM, is seen as an innovative approach (Mohammed et al., 2024) that leads to an emerging CRM approach positioned at the intersection of social media and traditional CRM, known as social CRM (SCRM) (Rostamzadeh et al., 2024). Based on the above, the authors postulated the following:

H4 IIWB positively influences the TCRM of a company.

OIWB, regarded as team and collaborative work behavior, as well as shared and empowering leadership (Hoch, 2013; Jankelová et al., 2021; Kmieciak, 2020), can result in innovations that contribute to the encouragement of CRM development and improved techniques and procedures in CRM (Binsaeed et al., 2023). Therefore, hypotheses were formulated about the association between OIWB and all components of CRM, as seen in Sin et al. (2005).

Collaborative innovation and shared actions are part of innovative processes at the organizational level and result in the development of customer-related competencies and relationships (Battistelli et al., 2019), as well as the enrichment of customer and brand experiences (Nguyen et al., 2019). A strong focus on key customers is triggered and supported by innovative processes at the organizational level, such as new forms of customer interaction, co-creation processes, interactive feedback mechanisms, and the use of artificial intelligence (AI) (Brătianu et al., 2023; Dastjerdi et al., 2023). Additionally, creative environments and innovative organizational climates, where innovations are prioritized (Halawa et al., 2023), contribute to better managing the customer life cycle and activities such as customer acquisition and retention (Jang et al., 2021). This focus on customers is based on new approaches such as using social media, which allow for enhanced customer experiences in terms of better service and stronger bonds with the brand (Rostamzadeh et al., 2024). Based on this, the authors assumed the following:

H5 OIWB positively influences the CO of a company.

An innovative organizational climate can also support the development of an organizational culture in which new CRM procedures are adopted to encourage employees in all departments to integrate customer communication and contribute to building value for customers (Binsaeed et al., 2023). This leads to developing powerful and long-term customer relationships (Ledro et al., 2022). Moreover, empowering, participative, and supportive leaders can motivate employees (Jong & Hartog, 2007) to cooperate and collaborate extensively to ensure cross-departmental communication about consumers (Mohammad et al., 2013), resulting in better CRMO. Further, workflow improvements are seen as the consequence of encouraging IWB at the organizational levels (Halawa et al., 2023). Additionally, innovative organizational behavior can lead to a stronger CRMO through innovative training that builds on previous CRM experiences, approached from an organizational learning perspective (Garrido-Moreno & Padilla-Meléndez, 2011). Such innovative CRM processes and organizations further contribute to developing sharing relationships with customers, which are at the heart of powerful CRM activities (Binsaeed et al., 2023). Thus, the authors assumed the following:

H6 OIWB positively influences the CRMO of a company.

The core issue in an organizational innovation process is the effective management of customer knowledge (Brătianu et al., 2023) as part of KM. Simultaneously, customer KM is highly favored by innovative processes for data collection, sharing, and utilization regarding customer behavior and context (Sin et al., 2005). Innovative organizational cultures also encourage the development of KM systems (Garrido-Moreno & Padilla-Meléndez, 2011) that gather and use detailed information about customers’ needs and preferences. Moreover, organizational policies that support innovation and leaders who foster a climate of creativity and openness to novelty for their teams may lead to new ways in which CRM conducts data gathering and analysis to understand customer expectations better while establishing better communication with them (Mansour et al., 2024). Therefore, the authors hypothesized the following:

H7 OIWB positively influences CRM KM within a company.

As a field, technology is highly related to innovations (Özel & Akgün, 2023) and is also seen as vital for the implementation of CRM (Dubey & Sangle, 2019). IWB results in higher digital literacy at both individual and organizational levels (Halawa et al., 2023), translating into greater IT integration within the company, including in CRM activities. OIWB, through the support of collective innovative initiatives and the organizational design and adoption of the latest information technologies, can lead to increased innovative CRM implementation, including the use of AI in CRM processes and chatbots for customer support services (Fernando et al., 2023; Nicolescu & Tudorache, 2022) to personalize customer experiences. Various other technologies can be integrated innovatively into CRM. For example, Ledro et al. (2022) highlighted the increasing role of AI in correctly interpreting large quantities of data, which can be used to better manage and build long-term relationships with customers. Meanwhile, social CRM emerges as a new approach to CRM (Rostamzadeh et al., 2024) that integrates social media technology into CRM processes at the company level to create better relationships with customers. Thus, the authors hypothesized the following:

H8 OIWB positively influences the TCRM of a company.

Many researchers characterize the relationship between CRM and organizational performance (including marketing performance) as robust (Fernando et al., 2023). Marketing performance is the facet of organizational performance that strongly relates to consumers. In this context, it is worth exploring how different dimensions of CRM as a consumer-centric activity impact MR, seen as customer-related performance.

Customer orientation plays an important role in organizational outcomes, as there is a direct relationship between customer orientation and firm performance (Racela, 2014), including marketing performance. CO places the customer at the center of the organization's activities to build beneficial long-term relationships (Garrido-Moreno & Padilla-Meléndez, 2011), thereby strengthening customer satisfaction and loyalty, which further reduces the costs of doing business (Sin et al., 2005). Thus, the authors assumed the following:

H9 CO of a company positively influences MR.

Organizations that have close interactions with their customers as part of their organizational cultures (Guerola-Navarro et al., 2021) can better respond to customer demands and create more value for customers (Jong & Hartog, 2010). Similarly, when customer interaction is required and rewarded via human resource management policies and practices (Garrido-Moreno and Padilla-Meléndez, 2011), the organization can achieve better performance in terms of customer trust (Yim et al., 2004), as well as the company's image and reputation (Sofi et al., 2020). Generally speaking, a good culture of CRM is seen as a condition for good organizational performance (Guerola-Navarro et al., 2021), including marketing performance. Thus, the authors hypothesized the following:

H10 CRMO of a company positively influences MR.

Customer knowledge of all types (rational, emotional, and cultural) (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 2019), when collected, analyzed, and interpreted in new ways, is seen as part of a CRM knowledge innovative system (Guerola-Navarro et al., 2021). Customer knowledge management innovative systems that include collaboration with stakeholders, such as company-client collaborations (Kang et al., 2015), impact CRM process performance and foster innovative outcomes (Brătianu et al., 2023), resulting in company and marketing success in terms of customer satisfaction and loyalty (Herman et al., 2021). Additionally, leveraging consumer knowledge via better knowledge management and dynamic management (Nicolescu & Nicolescu, 2014) results in increased customer interaction (Fernando et al., 2023). Thus, the authors posited the following:

H11 CRM KM within a company positively influences MR.

The integration of modern technology in CRM practices is regarded as a current trend in the development of CRM (Fernando et al., 2023). Various benefits are associated with the adoption and extension of technology usage in CRM, including in-depth data analysis and integration of internal and external sources of data (Zerbino et al., 2018), the development of new communication channels with customers (Sofi et al., 2020), and the development of customized applications that utilize AI (Ledro et al., 2022). In general, there is a significant relationship between TCRM and company performance (Chang et al., 2010), including marketing performance. In this context, the integration of up-to-date technology in CRM can contribute to increased efficiency and effectiveness of CRM, as well as increased customer satisfaction (Bhat & Darzi, 2016) and an improved overall customer experience (Fernando et al., 2023), which is a measure of marketing success (Herman et al., 2021). Good company performance (including marketing performance) is seen to be conditioned by the intensive usage of CRM technology (Guerola-Navarro et al., 2021). Thus, these lead to the following assumption:

H12 TCRM of a company positively influences MR.

Fig. 1 illustrates the conceptual model and the associated hypotheses tested in the present research.

MethodologySampling and data collectionThe study addressed employees from various organizations operating in different fields of activity. The sample was formed by combining purposive and convenience sampling methods, using a mixed purposeful sampling approach (Nyimbili & Nyimbili, 2024). The sample had purposive characteristics as, initially, the targeted respondents were employees working in departments involving direct customer relationship activities, holding positions in departments such as marketing, sales, and customer service. These types of employees possess rich information about CRM activities at the company level. However, later, to increase the sample size, employees working in other departments were also included, as company results obtained from CRM and company success also depend on employees across the entire organization (Hanaysha & Al-Shaikh, 2022; Nicolescu & Nicolescu, 2011) and not only on employees from designated CRM departments. Overall, it can be stated that the participating employees represent knowledge workers with specific CRM knowledge and are seen as generating added value for the organizations they work for (Toth et al., 2020), as well as contributing to organizational performance (Nicolescu & Nicolescu, 2011), including specific marketing performances. Nevertheless, 87 % of the respondents in the final sample were employed in departments directly involved in CRM activities (see Table 2). The sample includes individuals who, at the time of data collection, held a job in an organization.

Demographic information of respondents and organizational profiles.

The convenience sampling method was used to approach potential respondents with the aforementioned characteristics through the authors’ personal connections, as well as social media and other internet-related means (email), as convenient sources that were accessible to the authors. As part of the convenience sampling, employees working for organizations operating in Romania were chosen, as it is the authors’ country of origin. However, given the novelty of the proposed model and the new relationships to be tested, Romania was considered a good starting point as it is a country with similar historical, cultural, economic, and political features to other countries in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE); thus, to a certain extent, it can represent the region. The combination of both convenience and purposive sampling is seen as a current practice for most studies being conducted, as acknowledged by authors such as Andrade (2021).

The minimum sample size was estimated based on the G*Power analysis, which was conducted before the data collection following the suggestion of Hair et al. (2022). The G*Power software (version 3.1.9.2.) was used to determine the appropriate sample size (Faul et al., 2007). The analysis was conducted using the most frequently used settings and values (Faul et al., 2009), namely, linear multiple regression, alpha of 0.05, power of 0.80, a medium size effect (f2 = 0.15), and 4 degrees of freedom (according to the number of predictors).

Based on the analysis, the desired sample size was determined to be 85. The sample in the present study was 131, surpassing the minimum threshold established via G*Power analysis.

Initially, a total of 150 employees were approached, out of which 137 filled in the questionnaires. After eliminating the incomplete questionnaires, the final sample comprised 131 respondents. Table 2 presents the main demographic characteristics of the respondents, as well as the profiles of the organizations they work for. The majority of the respondents (84 %) were Romanians, while 10 % were nationals of other countries in CEE and 6 % were from other European countries. Therefore, the results reflect the Romanian situation and, to a limited extent, the situation in CEE (given that Romania is part of CEE and most of the foreign nationals included in the study came from other CEE countries, resulting in 94 % of the respondents being from CEE).

Techniques and methodsThe conceptual model and the associated hypotheses (see Fig. 1) were tested using SEM and partial least squares (PLS) with the software SmartPLS 4.0 (Ringle et al., 2022). This particular data analysis technique was selected for several reasons. First, PLS-SEM approaches a causal-predictive paradigm (Sarstedt et al., 2021), making it attractive for testing new models, as is the case in the present research. As the relationships tested in this research have not been explored previously, the model is entirely novel. Second, the structural model includes numerous constructs (7), items (37), and linkages (12). For investigating relationships between a large number of constructs, as proposed by the study's objectives, PLS-SEM is an ideal method (Hair et al., 2022). Third, the method is considered effective for small samples, such as the one in the present research (Hair et al., 2022; Henseler et al., 2016).

Questionnaire design and measuresThe conceptual model considers seven constructs that serve as latent variables: IIWB, OIWB; four components of CRM as defined in the literature (Sin et al., 2005)—CO, CRMO, CRM KM, and TCRM—and the final variable, MR. All variables were operationalized according to previous literature, as presented in Table 3. The variables were reflective in nature and measured using a Likert scale. The scales that were used, along with the constructs and items incorporated into the final model, are also included in Table 3.

Constructs’ and items’ reliability and validity.

| Constructs and Items | Item Loading | Cronbach's Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Individual Innovative Work Behavior (Reflective Construct)(Hoch, 2013; Janssen, 2000; Kmieciak, 2020) | 0.898 | 0.922 | 0.662 | |

| IIWB1. At my workplace, I create new ideas concerning solutions for difficult problems. | 0.809 | |||

| IIWB2. At my workplace, I search for new working methods, new techniques, new instruments, and new solutions. | 0.845 | |||

| IIWB3. At my workplace, I generate original solutions for existing problems. | 0.821 | |||

| IIWB4. At my workplace, I am able to transform new ideas into useful applications. | 0.813 | |||

| IIWB5. At my workplace, I implement innovative ideas in the work environment. | 0.814 | |||

| IIWB6. At my workplace, I evaluate the utility of new ideas after implementing them. | 0.778 | |||

| 2. Organizational innovative work behavior (Reflective Construct)(Bysted, 2013; Garrido-Moreno & Padilla-Meléndez, 2011; Hoch, 2013; Jong & Hartog, 2007; Yuan & Woodman, 2010) | 0.894 | 0.917 | 0.613 | |

| OIWB1. In my organization, creativity is encouraged. | 0.793 | |||

| OIWB2. In my organization, employees are allowed and encouraged to solve problems in different ways. | 0.746 | |||

| OIWB3. My organization's culture stimulates the acquisition of new knowledge among employees. | 0.807 | |||

| OIWB4. My organization is flexible and continuously implements changes. | 0.781 | |||

| OIWB6. My team leader encourages me to learn new things. | 0.824 | |||

| OIWB7. My leader encourages me to think creatively and come up with new ideas. | 0.831 | |||

| OIWB9. My leader recognizes and praises innovative performances. | 0.690 | |||

| 3. Customer Relationship Management Dimensions (Sin et al., 2005) | 0.898 | 0.925 | 0.711 | |

| 3.1. Customer Orientation (Reflective Construct)(Garrido-Moreno & Padilla-Meléndez, 2011; Khanh et al., 2021; Sin et al., 2005; Yim et al., 2004) | ||||

| CO1. In my organization, business objectives are focused on customer satisfaction. | 0.871 | |||

| CO2. My organization provides customized services and products to our key customers. | 0.828 | |||

| CO3. My organization makes an effort to find out the needs of our key customers. | 0.866 | |||

| CO5. My organization usually measures customer satisfaction. | 0.845 | |||

| CO6. My organization pays great attention to after-sales services. | 0.804 | |||

| 3.2. CRM Organization (Reflective Construct)(Sin et al., 2005; Yim et al., 2005) | 0.876 | 0.914 | 0.728 | |

| CRMO1. My organization has established clear business goals related to customer acquisition, development, retention, and reactivation. | 0.863 | |||

| CRMO2. My organization commits time and resources to managing customer relationships. | 0.892 | |||

| CRMO3. My organization has the sales and marketing expertise and resources to succeed in CRM. | 0.880 | |||

| CRMO4. In my organization, employee training programs are designed to develop the skills required for acquiring and deepening customer relationships. | 0.773 | |||

| 3.3. CRM Knowledge Management (Reflective Construct)(Khanh et al., 2021; Sin et al., 2005) | 0.862 | 0.916 | 0.784 | |

| KM2. My organization has set up processes to collect customer knowledge. | 0.877 | |||

| KM3. My organization has accurate information about customers, allowing for quick and accurate interaction with them. | 0.904 | |||

| KM4. My organization can make quick decisions with new knowledge obtained from customers. | 0.875 | |||

| 3.4. Technology-Based CRM (Reflective Construct)(Garrido-Moreno & Padilla-Meléndez, 2011; Pozza et al., 2018;Reinartz et al., 2004;Wang & Feng, 2012) | 0.924 | 0.94 | 0.813 | |

| TCRM1. My organization is able to consolidate all information acquired about customers in a comprehensive, centralized, up-to-date database. | 0.877 | |||

| TCRM2. My organization has dedicated CRM technology (software and hardware) in place. | 0.908 | |||

| TCRM3. My organization invests in technology to acquire and manage “real-time” customer information and feedback. | 0.925 | |||

| TCRM4. My organization uses hardware and software applications for data warehousing, analytics, CRM knowledge management, segmentation, and business intelligence—analytical CRM. | 0.898 | |||

| 4. CRM Marketing Results (Reflective Construct)(Garrido-Moreno & Padilla-Meléndez, 2011; Khanh et al., 2021) | 0.917 | 0.941 | 0.800 | |

| MR1. In my organization, CRM improves the image and prestige of the company. | 0.854 | |||

| MR2. In my organization, CRM enhances customers’ trust in the company and its products. | 0.900 | |||

| MR3. In my organization, CRM improves customer satisfaction. | 0.931 | |||

| MR4. In my organization, CRM improves customer loyalty. | 0.892 |

Source: The measurement statements rely on already established scales, as indicated for each construct.

Note: Item Loading > 0.70 (Hair et al., 2022); Cronbach's Alpha > 0.70 (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994); AVE > 0.5 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981); CR > 0.7 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

The analysis began with the evaluation of the measurement model. After ensuring the model's reliability and validity, the structural model was evaluated and the hypotheses were tested, as suggested in the literature (Hair et al., 2022).

The measurement modelThe measurement model of the present research was evaluated in terms of the validity and reliability of items and constructs.

The content validity of the items was ensured by adapting measures proposed in the literature and already validated by other researchers in previous studies. The reliability of items was measured by factor loading, with a recommended threshold of at least 0.7 (Hair et al., 2022). Based on this, out of the 37 initial items that belonged to the seven constructs, the final model contained 33 items within the seven constructs. See Table 3 for the reliability and validity of items and constructs.

All seven constructs demonstrated internal consistency reliability by conforming to the minimum acceptable limits for Cronbach's alpha (> 0.70) (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994) and composite reliability (CR > 0.70) (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Construct validity was evaluated by assessing convergent validity and discriminant validity. Table 3 illustrates that all constructs have convergent validity, as the average variance extracted (AVE) values were above the minimum limit of 0.50 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), ensuring that each construct explains at least half of the variance of the items. In the present research, the lowest AVE belonged to the OIWB construct (AVE = 0.613), and the highest AVE belonged to the technology-based CRM construct (AVE = 0.813).

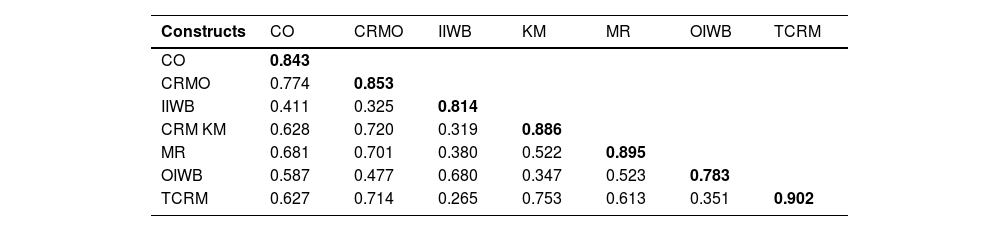

The discriminant validity of constructs was assessed using two criteria: the Fornell and Larcker criterion (see Table 4) and the Heterotrait-Monotrait criterion (see Table 5), as an additional test recommended by Henseler et al. (2016) for a more reliable measure of discriminant validity. The recommended thresholds were met for both criteria, illustrating that all seven constructs have discriminant validity.

Fornell-Larcker Criterion.

Note: The bolded diagonals illustrating the square root of AVE must be higher than the off-diagonal correlations situated below the diagonal line (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Heterotrait-Monotrait Criterion.

| Constructs | CO | CRMO | IIWB | KM | MR | OIWB | TCRM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO | |||||||

| CRMO | 0.868 | ||||||

| IIWB | 0.451 | 0.354 | |||||

| CRM KM | 0.716 | 0.846 | 0.357 | ||||

| MR | 0.743 | 0.766 | 0.411 | 0.579 | |||

| OIWB | 0.652 | 0.523 | 0.758 | 0.392 | 0.574 | ||

| TCRM | 0.686 | 0.805 | 0.283 | 0.844 | 0.662 | 0.382 |

Note: All values must be under 0.9 (Henseler et al., 2016) to avoid conceptual similarity.

The analysis of the collinearity of the measurement model was conducted by first examining the variance inflation factors (VIF) for items and then the VIF for the inner model. For both measures, the recommended value is a maximum of 5 (Rogerson, 2015), indicating no collinearity. The research data shows that the VIF values for items range between 1.601 and 4.860, indicating no collinearity in the existing data set of the sample. The VIF for the inner model is presented when evaluating the structural model.

The structural modelFollowing the procedure outlined by Sarstedt et al. (2021), the first step in measuring the structural model is to assess multicollinearity between the constructs. The analysis of the VIFs for the inner model shows that the highest variance inflation factor is 3.458 (CRMO -> MR). Since all VIF values are lower than 5, collinearity between constructs is not an issue for the structural model of this research.

The saturated square root mean residual (SRMR) was used to evaluate the model fit. With a residual SRMR of 0.065 (< 0.10) (Hu & Bentler, 1999), the model's goodness of fit is acceptable.

Overall, the four dimensions of CRM explain 56.1 % of the variance in marketing results determined by CRM (R2 = 0.561), whereas IWB explains 34.5 % of the variance of the CO (R2 = 0.345), 22.8 % of the variation of the CRMO (R2 = 0.228), 13.3 % of the variance in CRM KM (R2 = 0.133), and 12.5 % of the variance in TCRM (R2 = 0.125). These results illustrate a moderate predictive power of the proposed structural model.

Further, as Table 6 illustrates, the analysis of the structural model shows the direct effects and their statistical significance levels.

The path coefficients and confirmation of the hypotheses.

Note: CI: Confidence Interval

The first four hypotheses (H1, H2, H3, and H4) assumed that IIWB positively influences each of the four dimensions of CRM. The findings, presented in Table 6, illustrate that none of the four dimensions of the CRM are influenced by the IWB at the individual level, as none of the path coefficients are statistically significant. Therefore, H1, H2, H3, and H4 are not supported by the data in the sample.

The next set of four hypotheses (H5, H6, H7, and H8) proposed a positive influence of OIWB on each of the four dimensions of CRM. H5, which assumed a favorable influence of OIWB on CO, is confirmed by the statistical findings (β = 0.571, p-value = 0.000), showing a strong and significant connection between the variables. H6 suggested that OIWB positively affects CRMO, and considering the results (β = 0.476, p-value = 0.000), this relationship is also accepted, illustrating a strong and positive impact of OIWB on CRMO. H7 proposed a positive relationship between OIWB and CRM KM. The results (β = 0.241, p-value = 0.058) show a weak positive relationship with a smaller level of statistical significance between the variables. However, based on these results, H7 is also confirmed. H8 posited that OIWB positively influences TCRM. The findings (β = 0.318, p-value = 0.004) indicate a positive and significant connection, leading to the confirmation of H8.

The third set of hypotheses considered the direct effects of the four components of CRM on the marketing results. Accordingly, H9 presumed that CO positively influences MR. The findings (β = 0.324, p-value = 0.007) highlight a positive connection of medium strength between CO and MR, thus H9 is confirmed. H10 assumed that CRMO favorably influences MR, and the results (β = 0.370, p-value = 0.034) show that the linkage between constructs is positive and significant; thus, H10 is supported by the data. H11 assumed a positive connection between CRM KM and the MR of a company. According to the results (β = -0.134, p-value = 0.251), CRM KM fails to positively influence the MR of a company, as the path coefficient is negative and the relationship is not statistically significant. Therefore, H11 is not supported in this study. Finally, H12 assumes that TCRM directly influences MR. The findings (β = 0.407, p-value = 0.000) confirm that technology-based CRM has a strong positive impact on the MR of a company; thus, H12 is accepted.

Post-hoc analysisA post-hoc analysis addressed the mediating role of CRM between IWB and MR. The analysis revealed that CRM components do not mediate the relationship between IIWB and MR. However, for the relationship between OIWB and MR, the total indirect effects were statistically significant. The analysis of the specific indirect effects between OIWB and MR showed that three out of four CRM components played a specific mediating role, illustrated by positive mediating relationships with varying levels of statistical significance: OIWB -> CO -> MR (β: 0.185, p-value: 0.025); OIWB -> CRMO -> MR (β: 0.176, p-value: 0.053); and OIWB -> TCRM -> MR (β: 0.079, p-value: 0.103). Notably, CO was found to have the most powerful mediating role, strengthening the relationship between OIWB and marketing performance.

DiscussionInnovative work behavior and customer relationship managementThe findings illustrate that IIWB does not directly influence any dimensions of CRM, nor does it indirectly influence organizational marketing success via CRM. These results may be explained by two possible factors, either individually or together. The first explanation reflects the current situation in Romania, both in terms of general Romanian cultural values and workplace behaviors. Sociologists and psychologists have identified two types of cultural features among Romanians: (1) positive features such as religiosity, love of beauty, intelligence, melancholy, wisdom, hesitation, obedience, resignation, modesty, and anonymity and (2) negative features such as passivity, timidity, indifference, lack of discipline, and lack of perseverance (Catană & Catană, 1999). In terms of Hofstede's cultural dimensions, Romanians are seen as collectivistic and not focused on self-assertion, with a high level of uncertainty avoidance reflected by a low capability to cope with ambiguity, a strong resistance to change, and a preference for operating within the safe limits of routines. Additionally, Romanians exhibit a high level of femininity, which underrates competition and self-achievement while favoring equality and solidarity (Dumbravă, 2017). These cultural features might indicate a low general level of individual desire to innovate. In terms of workplace behaviors, Romanian managers are found to dislike risks (Catană & Catană, 1999), and although Romanians are perceived as creative, their inventive will is impeded by extreme caution when applying innovative ideas in practice (Dumbravă, 2017). Furthermore, innovation in the workplace is not the norm, and traditional individual work behavior tends to relate to routines and rules, with decisions taken rationally rather than innovatively (Brătianu et al., 2023).

The second possible explanation, which could also encompass the first, might be that there is no linkage between IIWB and CRM in general. This is difficult to conclude as there are no other studies examining this specific association of variables to support such a conclusion. However, within the same broad area of study, it can be appreciated that the results of the present study align with Lukes and Ute's (2017) research. They emphasize in a multinational context that employees in corporations very seldom implement original ideas without their supervisors’ approval and generally expect clear instructions from them, rather than being proactively innovative.

Conversely, OIWB was found to significantly influence CRM in terms of CO, CRMO, and TCRM. Other studies have identified various factors influencing CRM adoption and development, including factors related to OIWB, such as the level of innovativeness in the organization, innovation of senior executives, knowledge dissemination, and an innovative organizational culture (Šebjan et al., 2014).

The results of the present study are also consistent with Brătianu et al. (2023), who stated that in Romania, innovative behaviors are more related to operations (i.e., CRMO) as a means to achieve performance, as opposed to developing innovative products and services. The findings of this research are partially consistent with those of Dastjerdi et al. (2023), which indicate that organizational factors such as information systems infrastructure and an organizational culture oriented toward technology (similar to OIWB) determine the adoption of AI-integrated CRM systems (i.e., TCRM).

Additionally, CRM reinforces (as a positive mediator) the relationship between OIWB and the marketing success of the company, indicating factors that contribute to increasing the impact of innovative behavior on the company's marketing results and performance. This adds to the existing literature that points out, at a more general level, the positive connection between innovative behaviors and organizational performance (Jankelová et al., 2021; Nam et al., 2019), including marketing performance.

Thus, it can be concluded that, in the cultural context of the present study, IIWB was not found to be a trigger to foster and improve CRM at the company level, whereas OIWB was found to be such a trigger. The higher influence of collective innovative work behavior on CRM is also supported by the cultural behaviors of Romanians, who are seen as passive in formal groups but become active in informal groups (Catană & Catană, 1999). Moreover, in Romanian companies, group tasks become a condition of innovation at the organizational level (Guțu, 2020). Additionally, Stănescu et al. (2021) identified the positive influence of a supportive climate (characterized by managers who welcome innovative thinking) on IWB within Romanian organizations.

All of the above suggest that companies in Romania should focus on creating mechanisms to support innovative behavior at the organizational rather than individual level to foster innovative CRM and further marketing performance. Companies, through their managerial cultures and climates and managers’ encouragement, may support groups of employees to behave innovatively toward CRM dimensions. For example, the development of the CO dimension can be enhanced through team IWB by identifying new ways of interactive co-creation marketing practices, where companies and customers interact at different stages of product design and production (Narayandas & Rangan, 2004) to create value based on cooperation, collaboration, and communication (Sin et al., 2005). The KM dimension can be improved by finding innovative ways to disseminate and share knowledge about the organization and the customers as a source of competitive advantage.

Customer relationship management and marketing resultsThe results of this study indicate a significant positive impact of CRM on the MR of a company. Such findings are consistent with other studies’ discoveries related to performance outcomes and CRM (AlQershi et al., 2020; Pozza et al., 2018; Sin et al., 2005), with the relationship between CRM and performance being seen as powerful (Nam et al., 2019). Additionally, Garrido-Moreno and Padilla-Meléndez (2011) identified positive influences of CRM perspectives (CO, KM acquisition, KM diffusion, and CRM technology) on MR specifically, although the relationships were found to be strongly mediated by organizational variables.

Similar to AlQershi et al. (2020), who used the same framework as ours for CRM analysis and found that three out of the four CRM dimensions (CO, KM, and TCRM) influence a company's performance, the present research also identified three dimensions of CRM (CO, CRMO, and TCRM) as positively influencing MR as a form of performance at the company level (Khanh et al., 2021). The two common dimensions reinforced in both studies were CO and TCRM. Therefore, similar to the present study, CO, in terms of developing durable relationships between companies and their consumers, is seen as a way to foster customer loyalty (Fernando et al., 2023) as one facet of good MR. Additionally, TCRM, recognized in the literature as an influencer of organizational performance (Guerola-Navarro et al., 2021), is also a factor that was found to influence MR in the present study. This confirms the opinions of other researchers (e.g., Fernando et al., 2023) that the integration of cutting-edge technology, such as AI and chatbots for customer service (Nicolescu & Tudorache, 2022), contributes to the enhancement of overall customer satisfaction as a component of marketing success (Khanh et al., 2021) in the context of CRM.

The findings of the present research align with the results obtained by Guerola-Navarro et al. (2021), who identified both TCRM and CRMO as factors favoring firm performance, as the use of CRM technology and the development of a CRM culture are conditions for firm performance, including marketing performance.

ConclusionsSummary of findingsThe purpose of the present study was to analyze the relationships between innovative work behavior (with its two forms: IIWB and OIWB) and customer relationship management (with its four dimensions: CO, CRMO, CRM KM, and TCRM) and marketing results measured as companies’ prestige and image, customers’ trust, satisfaction, and loyalty. The summary of findings presented below illustrates how the investigation answers the initial research questions posed at the beginning of the study: (RQ1) how does IWB influence CRM? and (RQ2) how does CRM influence MR?

The main findings of the study are as follows:

- (a)

In the context of the present study, IIWB does not directly influence overall CRM and does not indirectly influence MR. Moreover, the indirect relationship between IIWB and marketing performance is not significant, supporting the lack of linkage between the two.

- (b)

OIWB positively and significantly influences all four dimensions of CRM in an organization, reconfirming that organizational innovation favors CRM activities (Jankelová et al., 2021).

RQ1 is, therefore, answered by indicating that only one form of IWB (OIWB) has a positive influence on all four CRM dimensions, while the other form of IWB (IIWB) has none.

- (a)

CRM positively mediates the relationship between OIWB and the marketing performance of the organization, and there is also a significant indirect relationship between OIWB and marketing performance.

- (b)

Overall, CRM favorably impacts the MR of an organization, as three out of four CRM dimensions (CO, CRMO, and TCRM) significantly and positively influence MR.

RQ2 is answered by illustrating that three out of four CRM dimensions positively influences marketing results at the company level, measured as prestige, trust, satisfaction, and loyalty of consumers.

The encouragement of OIWB seems to be more influential on the development of CRM activities and dimensions and indirectly on MR obtained by the company than the perception of employees on their own personal IWB. This can be explained by the fact that in Romania, actions taken at the company level are crucial for employees and have a high influence on the overall well-being of the company. Simultaneously, taking individual initiative at the workplace is not customary for Romanian employees (Brătianu et al., 2023) and has less importance and impact on CRM and, consequently, on marketing results.

The findings of the present investigation may have practical applications for managers. The positive influence of OIWB on CO can be leveraged at the company level. For example, collective IWB, if encouraged by managers, can contribute to the development of customer-centric marketing techniques. These may include new forms of personalization and tailored products that reduce the customer's time spent searching for and choosing the needed product (Chandra et al., 2022). Additionally, the positive influence of OIWB on CRM can be utilized at the company level. For instance, supporting team IWB can contribute to the development of organizational structures that facilitate seamless CRM communication across all departments (Mohammad et al., 2013), thereby improving CRMO.

Originality and research implicationsThis research advances theoretical understanding by contributing to the literature on both CRM and IWB, enriching these fields by establishing new types of relationships between them, illustrating that OIWB is a precursor to the CRM dimensions and identifying the mediating role played by CRM between IWB and MR. The study also reinforces the contribution of CRM to a company's MR and success. Previous studies examined how CRM influences innovations and IWB (Binsaeed et al., 2023; Guerola-Navarro et al., 2021), but the influence of IWB on CRM was underexplored. Therefore, this paper represents an original endeavor to analyzing the connection between IWB and CRM, proving the influence of OIWB on CRM. Another element of originality is the introduction of the distinction between individual and organizational IWB within an organization. This distinction proved relevant as the empirical study illustrates different connections between the two types of innovative behavior and CRM in the analyzed context. Further, the study also contributes to the IWB literature by adding an analysis of the influence and consequences of IWB on specific company activities and processes (such as CRM) and, subsequently, on organizational performance (measured by marketing results).

In practical terms, the study's results have real-world applications. The two major favorable connections confirmed in this research can be leveraged at the company level. First, the favorable impact of OIWB on CRM can be explored by creating an innovation-supporting climate and work atmosphere. This can be achieved through HRM practices that motivate and reward innovative behaviors, encouraging the generation, promotion, and implementation of new ideas related to CRM activities. Examples include new technical CRM tools for customer communication, novel venues, and increased flexibility and adaptability in responding to customer needs based on acquired knowledge. Second, as the study reinforces prior research findings indicating the positive influence of CRM on the MR and considering the positive mediating role of CRM in the relationship between OIWB and MR, managers should implement innovative, customer-centered CRM strategies that create value for customers and the organization. Such strategies can include customer-centered management supported by up-to-date IT technology (e.g., AI-based communication, customer data mining, automated processes, chatbot customer services), as AI is seen as the next step towards innovative CRM (Ledro et al., 2022).

The study holds significant implications for both theory and practice, as it tests and partially validates new associations between IWB and CRM, providing insights that can help managers find new ways to increase their competitiveness by supporting collective innovative work behavior at the organizational level.

Limitations and directions for future researchLike many other studies, this research has limitations. One such limitation is the small size of the population examined in the study, which, although above the minimum required size, was affected by company policies and the national context. Another limitation is that the data collection was exclusive to one country, Romania, limiting the generalizability of the results. However, given the economic, cultural, and political similarities with other countries in CEE, the results are relevant to the entire region. A third limitation is the soft measurement of marketing results, which is based on image, trust, satisfaction, and loyalty, thus lacking specific quantitative measures.

To overcome these limitations, future studies could examine the relationship between IWB and CRM in other national and international contexts to ensure higher generalizability and allow for comparisons. Another direction for future research could focus on specific business sectors, such as e-commerce, finance and banking, tourism, and travel, to identify sector-specific relationships.

CRediT authorship contribution statementLuminița Nicolescu: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Software, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Alexandru Ioan Rîpa: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.