Small nonprofit organizations (SNPOs) are a large part of the growing nonprofit sector. These nonprofit organizations (NPOs) generally receive $100,000–$250,000 in annual revenue. These entities operate similarly to for-profit businesses, with a mission, values, and dependable employees. One factor that sets SNPOs apart from for-profit organizations is the ability that for-profit entities have to provide higher, more competitive wages and better benefit packages for employees. NPOs often lack this ability, which can result in staffing challenges and high turnover rates. This study explores the different ways these NPOs attract employees, the types of incentives or benefits offered, and what can help retain employees once they are hired. The concept of employee commitment is also explored in the context of SNPOs. This information can provide SNPOs with a better understanding of talent acquisition and retention strategies that can lead to improved operational and strategic planning.

While government regulations and generating revenue top the list of challenges for nonprofit organizations (NPOs) in a national 2018 survey, one of the bigger problems nonprofits face is attracting and retaining employees (Bhati & Manimala, 2011; Jones, 2015; Wipfli, 2018). Though small nonprofit organizations (SNPOs) likely receive help from volunteers at times, they still need qualified employees to help maintain operations in the organization (Irwin et al., 2018). To address this problem, this study investigates what helps attract and retain employees to work for a SNPO. Since these organizations are thought by many to earn no profits, common questions include why would someone want to work for this type of organization and how do nonprofits attract employees?

Aside from attracting employees, an immediate concern for nonprofit leaders is retaining the employees once they find them. Nonprofit organization leaders have begun to explore and examine organizational factors that challenge the commitment from employees as they plan to fulfill the needs of clients, patients, customers and other stakeholders (Wallace, 2018). Research has shown that factors such as pay, working conditions, job satisfaction, and organizational policies all play a big role in determining employee commitment and the intent to stay in the job (Joo, Yoon, & Jeung, 2012; Salami, 2008; Wallace, 2018).

More specifically, can NPOs offer competitive pay and benefits in the same aspect as a for-profit business? We are interested in finding what NPOs, and in particular SNPOs, are able to offer that can help retain employees and yield lower turnover rates. Nonprofits are known to give back to the community, but at the same time, depend on the community for assistance, which presents a unique situation. As such, volunteers are essential to the organizations, but it is the employees that are the real backbone of the operation (Nelson, 2018).

Research conducted by Anne Preston has concluded that some employees in NPOs are willing to work for reduced wages if they are working for an organization that is generating a positive social outlook (Preston, 1989). This can be classified as an employee donating their time to help the cause of the organization (Jones, 2015). This type of employment is not volunteerism, which is defined as “long-term, planned, prosocial behaviors that benefit strangers and occur within an organizational setting” (Penner, 2002: 448). Instead, it is simply working for a smaller wage than they would earn with a for-profit business.

Other studies found that it is in the best interest of the organization to promote a working environment that relates to the beliefs and values of the organization (Emanuele & Higgins, 2000). This may seem like common sense and leads to the question: why would the organization not promote an environment that follows its beliefs? The answer is that these studies are more about promoting an effective corporate culture to reflect the values of the organization (Emanuele & Higgins, 2000). This illustrates the concept of employees “donating” their wages for the greater cause of the organization. If employees enjoy their work, have a pleasant work environment, feel like they are part of a community and the organizational culture is supportive and team-oriented, they are typically more willing to accept the lower wages (Robineau, Ohana, & Swaton, 2015). Employees may view this concept as donating their personal value. Some argue this can be in contrast to the fact that volunteers also donate their value without any wages in return (Preston, 1989; Weisbrod, 1983). However, the difference is that volunteers can be temporary with little to no organizational commitment. While this can also be true of employees, employees with adequate support from their organization work harder, display positive attitudes and behaviors and develop strong emotional bonds to the organization (Wang & Wang, 2020). Knapp, Smith, and Sprinkle (2017) offer evidence that nonprofit employees care less about the job duties and more about how they are treated indicating certain management techniques can improve job satisfaction and decrease turnover.

Also, we can better understand the importance of employee retention efforts by examining restrictions on sources of funding for NPOs. Donations from individuals and institutions, grants from foundations, and government funding are typically restricted forms of funding for program specific needs and not salaries, benefits, incentives or training programs (Bhati & Manimala, 2011). Such an environment requires human resource practices that work to decrease employee turnover and reduce service disruption to clients or customers. Some donors often focus on overhead expenses as a measure of effectiveness and attempt to exert pressure on charitable organizations to operate with low overhead. Dan Pallotta’s 2013 TED talk brought this issue to light and challenged the long standing “best practice” of low overhead for NPOs when society is asking them to solve big social, environmental, political problems (May, 2014). Overhead expenses were further explored in a study by Gneezy, Keenan, and Gneezy (2014) that concluded donations decrease when overhead increases. Since salaries and associated benefits are often lumped into administrative costs and overhead expenses, NPOs struggle with fundraising for budget items like salaries. Donors want to know their contributions make a direct impact and few get the satisfaction associated with “doing good” when their contribution pays the salary of a staff member (Gneezy et al., 2014). The lack of adequate funding for competitive salaries, ongoing training and benefits negatively impact employee retention. Actions centered on building commitment to the organization and focusing on relationships between employees and employers and amongst employees themselves can reduce the turnover rate (Beudean, 2009).

This research explores the staffing challenges within the nonprofit sector, and more specifically, the unique circumstances associated with SNPOs. The research questions lie at the intersection of human resource management and NPO operations. While studies have been conducted in this general topic area (Alatrista & Arrowsmith, 2004; Devaro & Brookshire, 2007; Stewart, 2016; Tierney, 2006), we intend to add to the body of sector specific literature by exploring further what SNPOs in particular could do to better attract and retain employees. Questions include: Are people looking for more pay or more/better benefits? What type of benefits do people find adequate? Is the right way to attract employees even related to pay or benefits? There are many questions that can be explored regarding staffing in SNPOs.

To better understand these questions and fill gaps in the literature, we contribute by presenting an overview of the theoretical perspectives that have been used to explain employee commitment, organizational purpose, financial motivation, and work with value. The relationship between family related considerations and values is also discussed. We conclude with the implications specific for all nonprofit managers and volunteer board members. As with many topics, this is an area that is constantly changing as new advancements in business operations, NPO governance, fundraising, technology and government regulations impact NPO management practices emerge.

The research noted above all connects with a common thread: human capital is critical to the service delivery and ultimate success or failure of NPOs. The pressure to do more, serve more, provide basic needs for more and use techniques typically used in for-profit organizations is causing conflicts. The interlinkages show there is pressure to become more efficient and effective while providing a work environment where employees feel a sense of ownership and importance within the organization. While this is a serious concern for NPOs, it is important to consider the challenges this situation presents for SNPOs with small budgets, little name recognition and only a few employees.

Nonprofit organizationsSNPOs are a type of NPO operating with a widely known tax-exempt business model. These are the smaller organizations that provide services to clients and partners in towns, cities and villages around the world in fields like education, health services, social services and community development. While size is difficult to quantify, the organization’s annual budget is used in this paper as a proxy for size. Using information from a variety of industry sources (Francis & Talansky, 2012; McKeever, 2018; ZipSprout, 2019), we establish the following general parameters to define size (1) unincorporated nonprofit associations are organizations that receive less than $5000 in annual revenue and no paid staff; (2) micro nonprofit organizations have annual budgets of less than $100,000 and 1–2 full time employees; (3) SNPOs generally receive $100,000–$250,000 in annual receipts with 3–10 full time employees; (4) mid-sized nonprofit organizations with an annual budget between $250,000–$500,000 with up to 50 employees and: (5) large nonprofit organizations with budgets between $500,000—over $1 million with 50+ employees.

With this in mind, a common misconception about SNPOs exists: many people assume that all nonprofit organizations (NPOs) are mainly staffed by volunteers, though this is not the case. Most NPOs are actually staffed by employees and professional managers that facilitate daily operations. Another common misconception is that NPOs do not actually retain any profits, they just raise money and expend it all while pursuing the attainment of some larger goals. Again, this is not always true. Best practices suggest creating some level of operating reserves such that a few months (minimum of 25% or three months of the annual operating budget) of operating expenses are always available (Grizzle, Sloan, & Kim, 2015). Net earnings, however, cannot be used to benefit any private individual or shareholder.

The modern concept of the NPO dates back to the 1970s when many groups were created to influence public policy or stimulate grassroots social movement (Hall, 2016). Today professionally managed NPOs provide specific kinds of services, engage in advocacy and public education initiatives and draw their revenues from a variety of sources (Hall, 2016). A SNPO is a type of NPO and can vary in size, scope and scale. These are typically grassroots organizations with few employees and limited assets. No matter the size, NPOs remain the stewards of public funds and private donations and have a responsibility to direct activities towards mission-related activities (Lecy & Searing, 2015). In fact, these organizations are legally prohibited from distributing earnings or profits to leaders or shareholders (Sanders & McClellan, 2014). While a nonprofit has the potential and ability to earn revenues, any surplus is used to achieve or further its purpose or goals, rather than being distributed as payment to members or other persons within the organization (Green & Kaine, 2013). Froelich (2000) noted that though NPOs can sometimes be viewed as less innovative than their for-profit counterparts, they may have a similar competitive potential and should not be underestimated. Being designated as a nonprofit does not necessarily mean the organization does not intend to make a profit; it simply implies there is no owner of the organization or shareholders. All SNPOs are governed by a board of directors and most also have paid staff such as program-specific employees and managers to assist with day-to-day operations. Tax-exempt IRS designation also requires the nonprofit organization to have a stated public purpose, serve a community need by offering goods or services and be governed by volunteer leaders (Seyam & Banerjee, 2018). As with any business, the success of a SNPO relies heavily upon its employees, board members, management, operations, and volunteers.

Employees play a key role in the success of any organization. Though many factors are at work in a successful operation, some key points include values, purpose, and motivation to encourage employees, as well as the culture of the organization. The management of the organization must use these factors in such a way to maintain the daily operations of the business in hopes of having an optimal employee mix. By motivating workers and generating positive work culture and values, the organization can operate smoothly and provide the best services to the public (Jones, 2015).

Employee commitmentEmployees and employers have a complex relationship that has been continually proven to impact the behavior and mindset of those individuals (Cole & Bruch, 2006). Since employee commitment is a component of motivation, motivation can be described as what directly causes employees to complete the task at hand (Meyer, Becker, & Vandenberghe, 2004). Employee commitment is in essence what causes an individual to carry out an activity which leads to completing a desired end goal or reaching a target (Meyer & Herscovitch, 2001). Employee commitment also involves the psychological aspects that causes them to form an attachment to their employer or organization (Allen & Meyer, 1990; O’Reilly & Chatman, 1986). An individual or employee may also have many different facets of motivation allowing for various types of commitment in relation to the goals within an organization (McDowell, Boyd, & Bowler, 2007; Meyer et al., 2004). Employee commitment is generally stronger when the individuals in an organization believe that they are being supported by the organization and the organization itself is committed to the individuals as well (Whitener, 2001).

Employee commitment within an organization can have an impact on job performance (Becker, Billings, Eveleth, & Gilbert, 1996). More specifically, employee commitment to supervisors has a direct effect on job performance and employees that are more committed to supervisors may exhibit more positive outcomes in terms of work performance (Becker et al., 1996). Another important aspect that can lead to commitment is an individual’s internal bond to an organization (Mahto, McDowell, & Davis, 2020). Klein, Molloy, and Brinsfield (2012) note that the bonds or psychological attachments to the workplace that employees experience can be situational. For example, an employee that feels bonded to their organization may experience a different type of bond than an employee that is bonded to a work team and so on.

This is important for organizations and managers to realize as it can allow them to understand what drives employee commitment in different areas and can also allow them to better influence and facilitate employee commitment within organizations (Klein et al., 2012). Employers must also understand that the way an individual perceives an existing bond is of the same importance as the process in which the bond was created with the individual (Klein et al., 2012; McDowell et al., 2007). Understanding the perception, forming and continuing malleability of bonds can be useful for employers and managers in terms of motivating individuals effectively, which can further lead to commitment (Klein et al., 2012). To enhance commitment at the individual level, Becker et al. (1996) suggest that motivating individuals in terms of supervisor’s goals and values through methods such as team building and socialization can influence job performance more than focusing on individual’s commitment to the organization. However, others note that the influence that an individual’s level of commitment to an organization can influence an employee’s turnover intention (Cole & Bruch, 2006; Mahto, Vora, McDowell, & Khanin, 2020). By considering what outcomes are expected of employees, organizations and managers can work backwards in determining what types of commitment will lead to desired outcomes (Meyer et al., 2004).

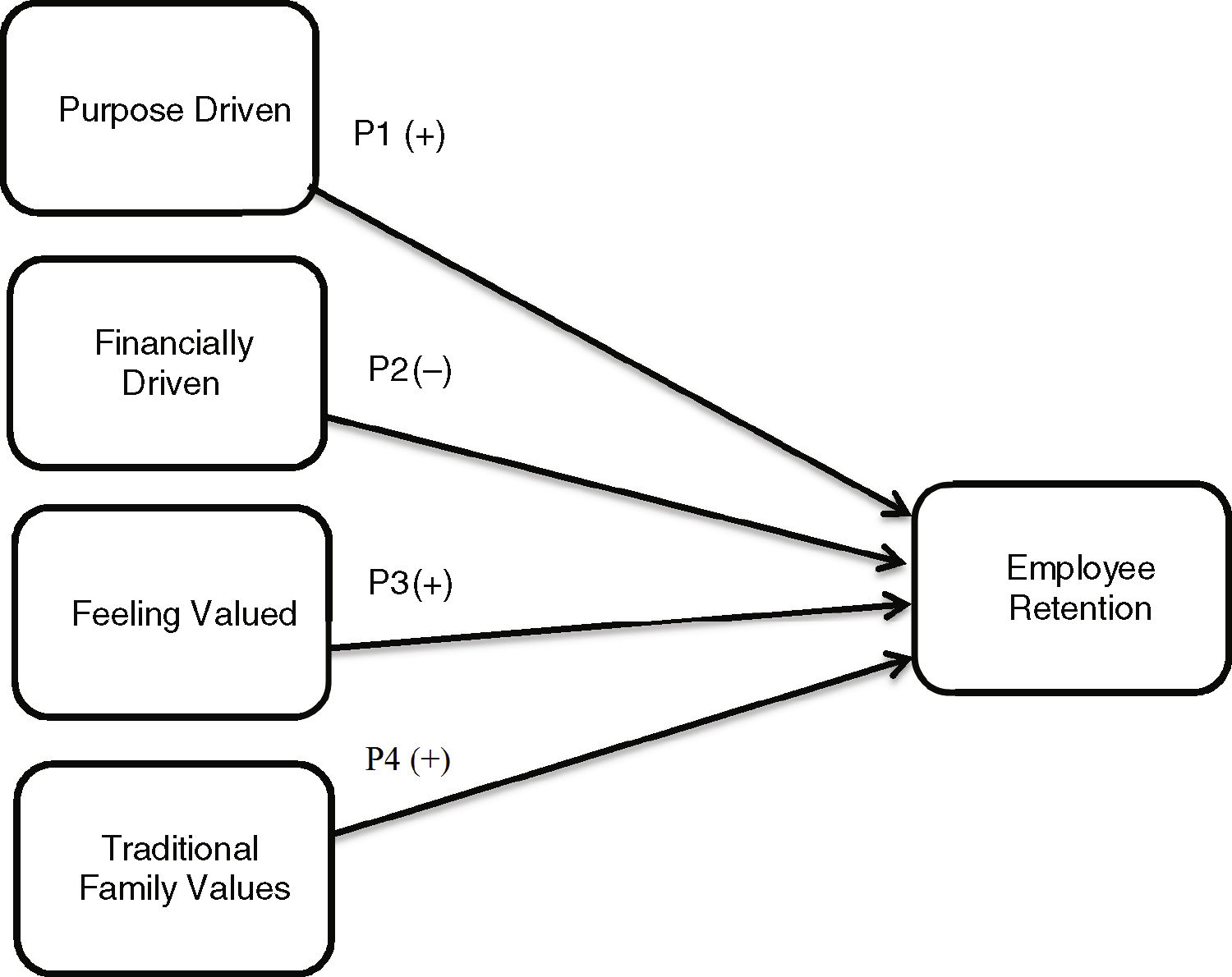

Employee commitment is especially important to consider in SNPOs where the central mission of the nonprofit can serve as a means of attracting and retaining employees (Brown & Yoshioka, 2003). If the mission of a SNPO is operationalized correctly, it can instill a sense of commitment within employees and keep them on track to fulfilling the purpose of the organization (Brown & Yoshioka, 2003). Employee commitment can also stem from organizations that encourage group loyalty and maintain a clear and direct focus on core values (Jaskyte, 2004). NPOs are unique in that employee commitment must often stem from non-financial areas, as nonprofits are generally more limited in terms of financial resources that can increase employee motivation and commitment (Alatrista & Arrowsmith, 2004). As such, the limited financial means within a SNPO can have a negative effect on employee commitment (Alatrista & Arrowsmith, 2004; Ridder & McCandless, 2010). Turner Parish, Cadwallader, and Busch (2008) note in their study using data collected from a SNPO that experiencing role autonomy can also lead employees to increased organizational commitment. Managers can continually track employee feedback in order to learn how to effectively foster and maintain successful relationships which can lead to greater employee satisfaction and commitment (Turner Parish et al., 2008) and ideally a better staff SNPOs. Smaller organizations also struggle in attracting talented employees because they are not widely known and lack any effective branding. Providing opportunities for professional growth by participating in conferences and workshops can positively impact employee commitment (Bhati & Manimala, 2011). In the following sections we present antecedents to retaining employee (or turning them over) in SNPOs. See Fig. 1 for an overview.

Organization purpose, mission & valuesWhen it comes to the performance of an organization, the individual employees may have more of an influence in the outcomes than the collective organization itself. Employees are recognized as one of the most significant assets to any organization (Ali, Lei, & Wei, 2018; McDowell, Peake, Coder, & Harris, 2018; Mesch, 2010). Identifying their own values with that of the organization, may give employees more of a purpose, increase organizational commitment, and create goals to work towards. That purpose is to drive the organization in the proper direction to ensure they attain their goals and mission. Major factors contributing to organizational commitment include job satisfaction (factors like working environment and working conditions, job security, the relationship between the manager and co-workers) and performance and productivity (Saha, 2016). More than in other types of organizations, employees in NPOs are actually attracted and motivated by a belief in the organization’s values and mission and the opportunity that the work offers to them to connect to their own values (Bhati & Manimala, 2011).

Employees that tend to be attracted to SNPOs are usually motivated in different ways compared to employees in a for-profit environment. SNPOs often have lower wages, therefore, pay is not usually a main form of motivation (Robineau et al., 2015). When employees are purpose driven to assist the organization in reaching goals, it indicates that they have high expectations of themselves. Employees in SNPOs are also generally working towards attaining some level of professionalism as Robineau et al. (2015) indicate that professionalism can sometimes be lacking in the nonprofit sector. Today’s employees at SNPOs are aiming to become tomorrow’s nonprofit leaders. In a 2006 study, Bridgespan Group predicted a need for top-notch nonprofit leaders based on growth in the sector and the pending retirement of baby boomers (Tierney, 2006). In the years since that report, NPOs have largely found leaders to fill the demand but turnover continues to be a major problem. With the increased availability of education and research, today’s generation of future SNPO leaders can more easily find the necessary professional skills required to add value to the organization. As such, strategic thinking, decision making, professional management, and financial management are all aspects of work that skilled employees can use to add value and purpose to an organization (Mesch, 2010). If any employee has taken time to become educated in these professional skills, they are likely purpose driven and determined to instill their values within the SNPO.

This information proposes that any business, SNPO or for-profit venture, should have a strategic plan in place to drive decision making, determine resource allocation and help maintain a successful organization (Mara, 2000). This strategic plan maps out where the organization is headed and lays out the future needs of the organization. However, SNPOs may struggle with the strategic planning process due to their more limited resources as compared to their larger or more sophisticated counterparts (Hussain et al., 2018; Mara, 2000). The first step in mapping out the strategic plan requires developing a vision statement charting the organization’s long-term direction, a mission statement that will describe the organization’s purpose, and a set of core values that can be used to guide the organization’s pursuit of the vision and mission statements. While the vision describes the organization’s future outlook, the mission describes the organization’s present business and purpose. The mission tells who the organization is, what they do, and why they exist. An organization’s values can be described as “the beliefs, traits, and behavioral norms that company personnel are expected to display in conducting the company’s business and pursuing its strategic vision and mission” (Thompson, Peteraf, Gamble, & Strickland, 2014: 21).

SNPOs can be considered to have a value-expressive nature about them. As with any organization, SNPOs typically have a vision, mission, and values. What SNPOs can offer is the opportunity for employees to participate at a high level in the decision making about the strategic priorities for the organization in the future. The mission of a nonprofit usually embodies and reflects its values as nonprofits tend to be held to higher ethical standards (Green & Kaine, 2013). A common type of characterization for this concept is “mission versus margin”, meaning the organization is more focused on following their mission rather than generating a high profit margin. The mission and values of these organizations tend to align with the purpose they are promoting, which is often a social service cause. SNPOs are viewed as being more humane and sensitive than government and for-profit organizations (Jeavons, 1992; Kramer, 1987). Research conducted by Peter F. Drucker found that the quality of decisions made in nonprofits plays a key role in determining if the organization is being run seriously, such that, its mission and values are meaningful to the public and not just in the public relations aspect (Drucker, 1990).

As with any organization, employees live and operate at work guided by their own personal values. If a nonprofit organization’s values are similar to and align with a potential employee’s values, this could help attract talent to the organization. If the organization’s values are similar to the potential employee’s, there is a greater chance they will want to work for the organization and stay for an extended period of time. It can give one a sense of helping the organization to achieve their goals, while also achieving their own personal goals. Therefore, we propose:Proposition 1 Purpose driven individuals are more likely to be retained at SNPOs.

An important factor for one to consider working for a NPO is that the wages are commonly lower than if an individual worked in a for-profit venture (Jones, 2015). Preston (1989) believes that some employees are accepting of this wage differential, because to them, they are donating value to the organization. Some employees may be more acceptable of lower wages because they consider the job to be a point of entry into the labor market (i.e. students). Having experience at a nonprofit organization may positively influence an individual’s resume, as some view work experience in this sector as a resume enhancer. Another important factor is that employees may have to start by making lower wages during training before eventually moving up to higher positions (Ehrenberg & Smith, 1994). Though, if employees are simply using the nonprofit job as a starting point for their career or to build up their resume, this could mean more employee turnover for the organization.

Employees could be more accepting of lower wages if they believe that by working hard and providing value to the organization, they may later be promoted and receive an increase in compensation. However, promotions may be less likely to occur in the nonprofit sector, which is illustrated by the fact that many SNPOs are flat when it comes to the organizational structure. Promotions can only occur when there is a higher position available in the organization. While promotions are possible in flat organizations they seem to happen less often in the nonprofit sector (Hansmann, 1996). Along with the structure of the organization, if employment growth is low, there can be both low and high rates of turnover associated with the decreased potential for promotions. For example, if there are lower turnover rates, promotions are more infrequent due to the lack of vacancies that need to be filled. In contrast, with higher turnover rates, the organization may not promote recently hired employees due to their inexperience. Both instances can result in an even greater number of turnovers due to lack of promotion and the possibility of earning higher wages (Devaro & Brookshire, 2007). Turnover events also have the potential to create a toxic working environment as employees are typically less protected from organizational change (Stewart, 2016). However, organizational change in SNPOs also has the potential to be exceptionally positive (Stewart, 2016).Proposition 2 Financially driven individuals are less likely to be retained at SNPOs.

Employees in NPOs are often attracted to the idea of being able to work toward a meaningful social mission. In other words, the mission of the organization has the ability to provide services to people, such as working in hospitals, with the elderly, or with children. These services are sometimes the reason why employees can be more accepting of lower wages because in return, they feel they can contribute to the mission of the organization. These mission driven values, considered a positive social mission, can serve as a form of intrinsic motivation to the employee if they believe it fits within their own value system (Devaro & Brookshire, 2007). The idea of a positive social mission tends to be more valued in the nonprofit sector than in for-profit ventures as the concept of creating a social good is generally the purpose of operations in a NPO (McDonald, 2007).

Employees that are attracted to intrinsic motivation rather than alternative incentives, such as promotions or raises, can at times be more dedicated and committed workers because they are working towards improving the organization. This type of motivation does not offer rewards, rather, it offers a sense of value. Intrinsic motivation can be defined as the effort that employees put forth in the absence of external rewards (Devaro & Brookshire, 2007). This motivation offers a greater significance and increases the degree of meaningfulness of the employee’s work. In turn, the increased significance yields a higher work performance from the employee (Hackman & Oldham, 1980). These findings help us propose:Proposition 3 Individuals feeling valued are more likely to be retained at SNPOs.

Low wages are known to be associated with working for a SNPO. Another aspect of employment that employees in these organizations tend to miss out on are benefits, such as health insurance and retirement fund contributions. However, SNPOs are often known to have more family inclusive policies. This can help attract employees that would prefer to have flextime or a part-time work schedule. A study conducted by Fernandez reveals that a determining factor in the ability to attract and retain loyal and productive employees stems from family sensitive fringe benefits and personnel policies (Fernandez, 1990). While there are multiple types of work arrangements, such as compressed workweeks, phased retirements, and telecommuting, the most common, and preferred, arrangements are part-time work, reduced workweek, and flextime. Flextime is found to be one of the most available throughout organizations (Hohl, 1996). This gives the employees the ability to make their own schedule, as long as they fulfill the required amount of hours to be worked. This is found to be helpful when families may not have access to affordable childcare or both parents work alternating hours. While many SNPOs are not able to offer benefits, those that can often attract individuals with spouses who are working. Considering this, it is possible that some of the individuals working in the nonprofit industry receive benefits from their spouse’s jobs, therefore allowing them to be more acceptable of working for an organization with limited resources.

Another common belief is that SNPOs tend to be more responsive to the family needs of employees than typical for-profit businesses. Research has shown that work-family conflict can lead to emotional exhaustion which leads to lower levels of satisfaction (McDowell et al., 2019). Since a majority of SNPOs are pursuing a purpose with good intentions, they tend to be held to higher standards, such as honesty, transparency and fairness. This can extend further beyond their organizational values. SNPOs are expected to not only maintain, but also promote behaviors that are caring, humane, and progressive towards their set of values (Jeavons, 1992). In conclusion, we propose:Proposition 4 Family related incentives and values will enhance retention at SNPOs.

Scholars continue to discuss important differences between smaller and larger organizations (e.g. Bendickson, Davis, Cowden, & Liguori, 2015; Davis & Bendickson, 2020), as well as the need for human resource practices at newer and smaller organizations (Bendickson, Muldoon, Liguori, & Midgett, 2017). We continue this conversation by conceptually expanding on issues of attraction and retention for SNPOs. As with any business, SNPOs need valuable employees to achieve their mission and facilitate daily operations. NPOs often find it difficult to attract and retain employees when providing lower wages than a for-profit business. Prior research has found that employees who feel the organization’s values relate to their own can be more attracted to work for a nonprofit organization. The mission-driven work can give employees a sense of purpose and value as they help the organization achieve its goals. Many considerations can impact employee commitment to the organization including personal factors (i.e. age, gender, education level and marital status) and organizational factors (i.e. job satisfaction, leadership style and organization climate) (Saha, 2016). These factors can make employees feel like they are contributing to the organization’s mission by “donating wages” when they accept lower wages than they would find elsewhere.

Aside from giving the employee a sense of value added to the organization, we wanted to determine the other ways SNPOs can attract and retain their employees and also if SNPOs have the capability to offer benefits, incentives, or promotions. We wanted to know not only the key factors to attracting potential employees to work for a SNPO, but also what makes them want to continue working for the organization.

Much of the prior research conducted focused more on wages and if that was a determining factor of pursuing an organization for those applying to work in NPOs. We wanted to look further than just wages, for example, we wanted to know if incentives were linked to an employee staying longer with the organization. Here lies a future research agenda. For example, research is emerging around the concept of talent management whereby compensation, benefits and incentives are the primary focus for successful management of employees (Allen, 2018). The Affordable Care Act does not require NPOs to provide medical coverage unless there are more than 50 full-time equivalent employees. Unfortunately, many SNPOs are not able to offer health benefits due to scarce financial resources, unpredictable funding and budgetary constraints. Typically, paid leave benefits like holidays, bereavement time, vacation days, bundled time off and sick leave are available in NPOs. In an attempt to be competitive, some are offering creative fringe benefits to make their organization even more attractive such as flexible schedules, casual dress, professional development programs, commuter assistance and wellness programs. We found that having the ability to control their own hours and spend more time with family is preferred by some individuals. Powell and Cortis (2017:167) noted that flexible work arrangements are one of the “compensating differentials” that employees will trade for lower wages. This may be especially significant if they are already eligible to receive other types of benefits from their spouse’s place of employment like health/dental/vision/disability insurance plans, tuition assistance, gym membership discounts, and retirement plan options.

Studies may also further investigate the topic of career advancement which is a major issue for most organizations in the nonprofit sector. Career advancement is typically achieved when an employee proceeds through a career path. This career path is a series of activities where, over a period of time, employees engage in professional development activities and take on greater responsibilities (Stewart & Kuenzi, 2018). Unfortunately, many employees in SNPOs will not receive any type of promotion during their employment with the organization. This is affected by both low and high rates of turnover. Allen (2018) reports that the average employee in a NPO will be employed only two to five years with that organization and those that remain past the five year mark tend to remain at the organization longer that the rate at which employees remain at for-profit companies. These results indicate NPOs are spending significant resources on hiring and retaining employees who do not stay with the organization long enough for the organization to recoup that investment (Allen, 2018). Another main factor is that many nonprofits have a flat organization structure with a minimal number of levels of formal authority (typically one), small number of different jobs and small number of different departments. In this environment, there are not many opportunities for promotion. These low promotion probabilities, along with fewer opportunities for pay raises could be a determining factor impacting employee satisfaction and retention. Promotions are infrequent when high turnover exists as the most recently hired worker has not been with the NPO long enough to receive a promotion (Devaro & Brookshire, 2007). Employees seeking higher financial rewards also impact high turnover rates. There is growing emphasis within the sector towards grooming and preparing future nonprofit executives (Stewart & Kuenzi, 2018).

Future research may also further investigate means to provide opportunities for personal growth, creating a sense of ownership by participating in decision-making and creating entrepreneurial opportunities for employees are also important factors when analyzing talent acquisition and retention in NPOs (Bhati & Manimala, 2011). Small organizations are well suited to provide these valuable hands-on opportunities for employees. An investment in creating opportunities for employees to have some autonomy, develop entrepreneurial skills, choose specific projects to develop or issues to investigate, and participation in decision making processes may yield substantial benefits for the SNPO at a later date. As employee management improves, so does productivity and retention (Bhati & Manimala, 2011).

Limitations and conclusionWhile we were able to draw upon many articles and past studies that informed our thinking on the questions being asked in this conceptual paper, there are always limitations. First, many of the studies were not current enough to take into consideration the modern challenges and pressures that NPOs face (i.e. crowdsource funding, competition from other NPOs, social entrepreneurship, retaining/engaging donors, changing government regulations and tax reforms, relationship marketing and modern technology changes). This could possibly mean that the topic of staffing in NPOs and, in particular, SNPOs is under-researched. Another limitation and concern is that much of the research conducted yielded the same or similar results. Without robust research, there are limited opportunities for comparison and/or contrast within the body of literature on the topic.

Staffing in NPOs can be studied continuously as workforce characteristics are always changing and evolving. Domiter and Marciszewska (2018) point out lacking the ability to manage employees has been one of the more costly mistakes in NPO management as human resources have the greatest impact on the future of the sector. Though our questions have been mostly answered, these answers can be completely different five years from now. Social norms, generational approaches to work (like Baby Boomers, Gen X, Gen Y, and Gen Z), employee age and gender, modern incentives such as flextime and freedom to set one’s own work hours, and the call for work/life balance bring new dimensions to staffing and talent management in NPOs. There will always be opportunities to study what will attract and retain employees in a SNPO. Now, employees may be happy with the option of having flextime or a shorter work week, but that may not be the case in the years to come. This topic should likely be continuously studied to provide the most accurate information possible in the future.

In all, we explored and discussed some key factors that play into what motivates a potential employee want to work for a SNPO. To some, working for an organization that shares the same values that they believe and follow attracts them. Not only do the organizational values attract employees, but also the belief that they actually add value to the organization, can give them a sense of purpose and drive them to perform better on the job. Others are attracted to the idea of being able to have flexible schedules allowing them to spend more time with their families. Higher wages and benefits may not be all that is needed to attract talented and dedicated employees. Still, while values and flexible hours may attract some, lack of/limited benefits, promotions, and raises can cause higher turnover rates for financially motivated employees.

SNPOs are all around us; these are the entities where we donate, volunteer and receive many social, cultural, educational or health services. The work of these small, but mighty, groups is done by volunteers and paid professional staff who seek out ways to fill unmet social needs in every community. In our discussion about size, what can’t be measured easily is impact – how many people are affected by the important work of these organizations. Working for a NPO is not for everyone, but those that choose to jump in, are giving in so many important ways to a cause greater than themselves. SNPOs offer the unique opportunity to work in partnership with employees to impact change and do social good while providing an environment for personal growth and professional development.