This study focuses on whether network media information about the COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on the online knowledge acquisition of college students. This research is of great significance, as it can have a profound impact on the way we think about knowledge acquisition in the future. Yet, a recent literature review finds that the academic community has not paid attention to this important topic. In the present work, which is based on a survey of 5000 Chinese college students during the COVID-19 pandemic period, we find that COVID-19 information from mainstream Chinese media and overseas media as well as social media has had a significant promoting effect on the online knowledge acquisition of college students. At the same time, the psychological response to the pandemic situation is shown to have had a significant mediating effect on the relationship between the information impact from mainstream Chinese and overseas media and the online knowledge acquisition of college students. Our findings have shown that the more positive college students are in responding to the pandemic, the stronger their willingness is to acquire knowledge through online means, and the better effect this will have on them acquiring knowledge. The results of this paper have important implications for the optimization and improvement of college students’ education and knowledge acquisition methods in the context of the long-term COVID-19 pandemic.

On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) designated COVID-19 a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC)” (Bao, Sun, Meng, Shi, & Lu, 2020). Soon afterwards, school closures became widespread so that the public could better maintain social distance and help prevent the spread of COVID-19. Yet, this situation has had a significant impact on college students’ knowledge acquisition methods. In general, the spread of highly infectious diseases will speed up information spread by rumors to a certain extent (Huang, Chen, & Ma, 2020). We thus find that the COVID-19 pandemic has also become an “information pandemic,” which has impacted college students’ mental health and knowledge learning. Pena and Lim (2020) argued that the debate within academic communities on the effectiveness of distance learning has never been as colorful as it is today when higher education institutions have shifted physical classrooms to online platforms during a global novel coronavirus pandemic. The situation that colleges and college students find themselves in, with wide-scale global online learning and remote instruction necessary due to COVID-19, is truly unprecedented (Fairlie & Loyalka, 2020).

In their work, some studies found that COVID-19 knowledge was positively correlated with attitudes and practices (Afzal, Khan, Qureshi, Saleem, & Ahmed, 2020). More specifically, they demonstrated that the impact of the media on individual behavioral changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic is embedded in transmission probability. Mukhta et al. (2020) stressed that recently implemented online learning modalities encourage student-centered learning and that these modalities are easily manageable during the COVID-19 era. However, other studies have provided contrary views, showing that pre-COVID-19, there was limited evidence regarding whether edtech affects academic outcomes, and that online programs can be implemented poorly (Escueta, Quan, Nickow, & Oreopoulos, 2017; Morgan, 2015, 2020).

The impact of pandemic information coming from network media will promote the online knowledge acquisition of college students to a certain extent. According to Utunen, Attias et al. (2020) during the early months of the pandemic, the largest traffic channels were search engines and social media, and Halim et al. (2020) stressed that the public got most of its information from social media instead of official COVID-19 government sites. Media reports can change people’s understanding of emerging infectious diseases, and as it pertains specifically to college students, such reports have been shown to change attitudes and behaviors (Yan et al., 2020). During the COVID-19 period, college student classes shifted from traditional classrooms to online environments. Yet, this was not necessarily negative, as in some research findings students’ knowledge and their discussion behaviors were shown to be significantly improved by online courses, and their awareness of the necessity of learning was also significantly strengthened (George et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020).

There are studies showing a correlation between pandemic psychology and online knowledge acquisition (Haider & Al-Salman, 2020; Yusoff et al., 2020). There have also been investigations into whether there is a correlation between the prolonged use of digital e-learning tools and the COVID-19 crisis (Elhai, Yang, McKay, & Asmundson, 2020). Overall, strict social and physical distancing measures have been aimed at minimizing the spread of COVID-19, and this situation has carved out a critical role for online learning as a solution to bridge the knowledge acquisition gap (Pena & Lim, 2020). For their part, many college students have demonstrated a willingness to acquire knowledge in online environments.

In this context, Dhawan (2020) has devoted his recent scholarly attention to the growth of edtech start-ups and has provided some suggestions for academic institutions to deal with challenges associated with online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sun and Su (2020) have stressed the importance of the suspension of in-person classes—without the suspension of school altogether—and the need to strengthen network teaching by supplying online teaching services while building network course platforms and live broadcast systems to ensure positive results from students’ online knowledge acquisition. As is well understood, e-learning has certain benefits and challenges (Kumar, 2019), but online courses during the pandemic have addressed a worldwide learning need (Utunen, Ngouille et al., 2020).

There have been a number of recent studies that have explored the new coronavirus pandemic situation and college students’ psychological reactions to it. For instance, Yang and Ma (2020) concluded that the onset of the coronavirus pandemic led to a 74% drop in overall emotional well-being. Some studies have also suggested that experiencing the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the prevalence of various mental health problems (Ho, Chee, & Ho, 2020; Sun & Su, 2020; Xiao et al., 2020). Liu et al. (2020) concluded that during the prevalence of COVID-19, many people have experienced emotional reactions to it, such as stress and fear, which should not be ignored, and which might continue after the pandemic has subsided. However, there is also research that leaves the emotional question more open. For example, based on multivariable logistic regression models used to analyze the association between the COVID-19 pandemic and the risk of anxiety and depression symptoms, Wang et al. (2020) concluded that the association between the pandemic and the risk of anxiety and depression in Chinese college students remains unclear.

Network media information on the COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on the online knowledge acquisition of college students, and this will very likely have a profound impact on knowledge acquisition in the future. However, in a recent literature review we conducted, we found that the academic community has yet to pay attention to this crucial issue. Accordingly, we focus this work on whether network media information on the COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on the online knowledge acquisition of college students. First, we study the impact of COVID-19 information found in both mainstream media and social media on college students’ online knowledge acquisition to better understand the change in methods of knowledge acquisition in this unique period. Second, we provide a research framework that takes the psychological response to the COVID-19 pandemic as an intermediary role in order to explore the relationship between pandemic psychology and online knowledge acquisition. This work reveals the positive impact of mental health on online knowledge acquisition for college students. Finally, we investigate the impact of pandemic information on college students’ psychological reactions and how this affects college students’ knowledge acquisition. Overall, this study has important implications for the optimization and improvement of college students’ education and knowledge acquisition methods during the COVID-19 era and in the future.

Theory and hypothesesImpact of network pandemic information and online knowledge acquisitionDuring a novel coronavirus pneumonia conference held in 2020, the WHO presented the concept of an “infodemic,” discussing how, during the pandemic, we are not only fighting the virus but also an information pandemic (Rajapathirana & Hui, 2018; Ricciardi, Zardini, & Rossignoli, 2018; Zarocostas, 2020). During this time, many people have been receiving information about the COVID-19 pandemic via social media, and this type of network media has been an important means for the public to obtain pandemic information, as it can quickly transmit information urgently needed by the general public, including pandemic information, response measures, policy interpretations, personal action suggestions, etc. (Hilton & Hunt, 2011). People’s perceptions and actions regarding the pandemic are interrelated, and those perceptions and actions are the results of the information they receive. The impact of network media information will objectively promote people’s online knowledge acquisition, including that of college students. Burke (2003) divided knowledge into academic knowledge and popular knowledge, according to the owner or producer of that knowledge.

In the Internet age, the form of knowledge display and the mode of knowledge transmission have changed from traditional methods to online forms. Weinberger (2014) emphasized that networked knowledge was no longer deterministic, but more humanized, inclusive, and pluralistic. During the COVID-19 pandemic, learning has not been quarantined: knowledge learning has been open, and knowledge acquisition has been continuous (Pena & Lim, 2020). Continuing through this challenging period, it is important to realize the level of knowledge accumulation via online learning, as well as to discover ways to leverage the positive relationship between the size of the network and the wealth of knowledge accrued by learners (Pena & Lim, 2020; Piñeiro-Chousa, López-Cabarcos, Romero-Castro, & Pérez-Pico, 2020).

The spatial isolation brought about by the pandemic has affected the social lives of individuals and has changed the space of knowledge production and consumption. Actor-network theory sees that every knowledge receiver, knowledge producer, and knowledge media carrier can be regarded as an actor (Choi, Yeo, & Won, 2018), thus forming a knowledge learning network. According to the “psychological typhoon eye effect,” just as when the air around a typhoon rotates violently, but the wind flow in the center is relatively weak (Lindell & Earle, 1983), the closer people are to the pandemic site, the more likely they are to abide by social distancing rules. As Hosupa (2012) found, the more individuals think they are at risk, the more likely they are to actively seek to acquire knowledge and information through online learning, eliminating the knowledge “fence”—the restrictions on knowledge acquisition—promoting the flow of all kinds of online knowledge.

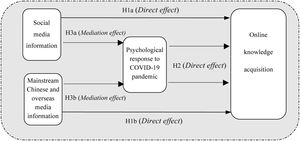

The Internet has become a source of various media channels and information, including official websites, social networks, and so on (Avery, 2010). Yet, crucially, in the current moment, the excessive amount, and often the low quality, of network information on the pandemic is affecting the knowledge acquisition of college students, which could easily produce psychological resistance, burnout, or other strong emotions and reactions. Therefore, it is particularly important to improve the level of network media governance and to cultivate media literacy as ways to help people eliminate some of the negative impacts of pandemic information. In China, there are two main forms of network pandemic information: the first is information regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic found on domestic social media, and the second is information regarding the impact of COVID-19 found on mainstream Chinese and overseas media. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses: Hypothesis 1

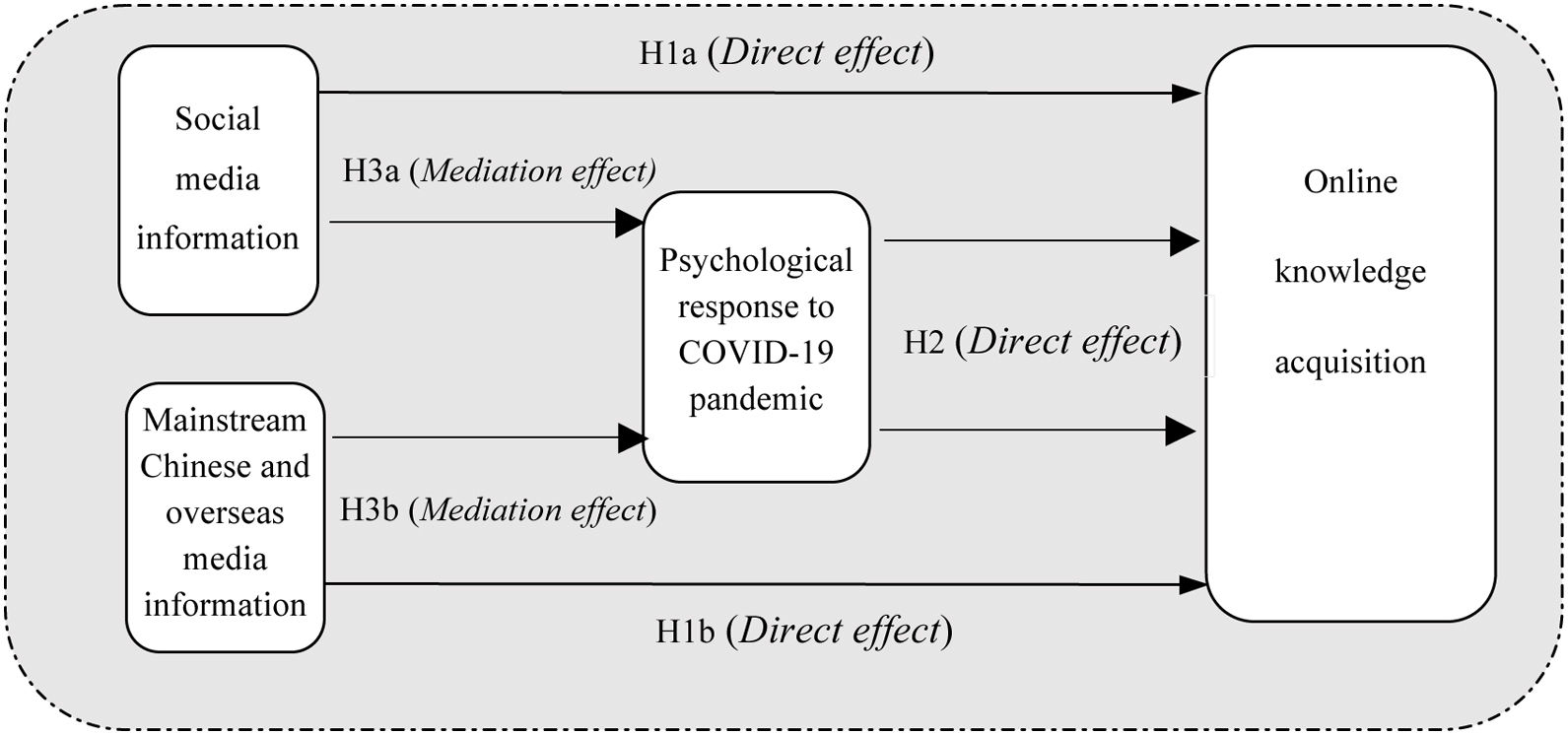

(H1): Network pandemic information has a positive impact on the online knowledge acquisition of college students.

Hypothesis 1a(H1a): Pandemic information found on domestic social media has a positive impact on the online knowledge acquisition of college students.

Hypothesis 1b(H1b): Pandemic information found on mainstream Chinese media and overseas media has a positive impact on the online knowledge acquisition of college students.

The psychological response to the COVID-19 pandemic and online knowledge acquisitionAffected by the use of social media, the perception of the pandemic at a personal level appears to be driving more positive interpersonal communication. Generally speaking, college students find it easy to accept new things, have a great deal of access to information, and engage in a high level of social media activity. However, due to long-term isolation at home and prolonged stress, college students may also have a greater susceptibility to stress stemming from the pandemic than other groups (Chan et al., 2020). On the whole, the healthier the psychological response to the pandemic is, the more favorable the situation will be for online knowledge acquisition. Most college students are active thinkers and can skillfully use the Internet and other means to obtain information and knowledge, making them the principal group to engage in new social technology and new ideas. In the era of the Internet, the opening of large-scale online courses, such as Tencent Classroom, Rain Classroom, School Online, and other learning platforms, has enriched the learning resources of college students, expanded their learning spaces, and provided a broader scope of autonomous learning choices.

Yet, as it pertains specifically to social media, the copious amount of information found there may lead to information overload, which could result in mental health problems (Gao et al., 2020). As expressed in the “stressor-strain-outcome model,” the excessive amount of pandemic information sent via social media exceeds the user’s ability to process and absorb it, which will have a negative impact on the psychology and behavior of social network users, thus affecting online knowledge acquisition (Dhir, Yossatorn, Kaur, & Chen, 2018; Whelan, Islam, & Brooks, 2020). Social media frequently push pandemic information into the world, where friends in social groups quickly and repeatedly retransmit this information, which can easily cause psychological negative emotions; to a certain extent, this can affect the willingness and enthusiasm of knowledge acquisition (Zhang, Zhao, Lu, & Yang, 2016). On the basis of the above, we put forward the following hypothesis:Hypothesis 2

(H2): Maintaining mental health in response to the COVID-19 pandemic has a positive impact on the online knowledge acquisition of college students.

The mediating effect of psychological response to the pandemic situationBawden and Robinson (2009) have stated that information anxiety is a state of pressure when an individual is unable to obtain, understand, or use information, and also that the level of information anxiety is affected by potential information overload, the individual’s understanding of the information environment, and the way the information is presented. Other studies have shown that the impact of network pandemic information can produce psychological reactions in college students, including depression and irritability, but occasionally also optimism, any one of which could easily affect the willingness and actions of university students to acquire knowledge (Halim et al., 2020; Ho et al., 2020). During the COVID-19 pandemic, online learning and traditional learning have varied greatly in the ways of acquiring, thinking about, and evaluating knowledge. The pressure that students may not be able to adapt to long-term home stays and other environmental concerns may easily bring about psychological depression, which will affect the knowledge learning effect on college students (Elhai et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020).

Due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, students’ endogenous growth potential has been greatly stimulated (Sun & Su, 2020). In other words, college students’ cognitive level of understanding the COVID-19 pandemic situation has been shown to be positively correlated with taking a positive response and negatively correlated with taking a negative response (Richelle et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). The higher the cognitive level is, the easier it is for college students to adopt positive coping styles, allowing them to learn actively and to achieve knowledge growth. Therefore, if college students have a more scientific understanding and rational view of the COVID-19 pandemic situation, they will be more likely to maintain their physical and mental health (Haider & Al-Salman, 2020; Yusoff et al., 2020). Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:Hypothesis 3

(H3): The psychological response of college students to the pandemic situation mediates the relationship between the information impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and online knowledge acquisition.

Hypothesis 3a(H3a): The psychological response of college students to the COVID-19 pandemic mediates the relationship between the pandemic information found on domestic Chinese social media and online knowledge acquisition.

Hypothesis 3b(H3b): The psychological response of college students to the COVID-19 pandemic mediates the relationship between the pandemic information found on mainstream Chinese and overseas media and online knowledge acquisition.

Based on the above literature analysis and theoretical assumptions, we present our hypotheses model in Fig. 1.

MethodologyData collectionFor this study, we used a survey method to collect data from Chinese college students. The research variables we investigated were based on existing scales and were measured on five-point Likert scales. This large-scale random stratified sampling survey on college students’ attitudes about the pandemic and their behavior was conducted in March 2020 by the New Media Data Research Institute of East China University of Political Science and Law.

First, to ensure validity, we conducted a pre-test by sending our initial questionnaire to 100 Chinese college students. Using their feedback, we verified the content, clarity, and wording of the survey items. After ensuring the validity of the questionnaire, we then sent a total of 5000 questionnaires to college students located throughout China. We received 2546 questionnaires back, of which we determined 2397 were valid, and thus, we had an effective response rate of 47.94%.

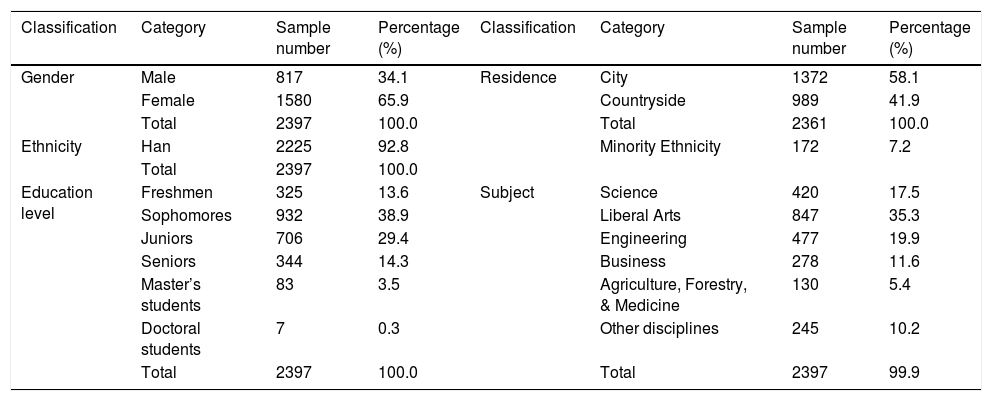

Sample statistical analysisThe sample covered highly representative demographic characteristics along five dimensions: gender, ethnicity, place of residence, grade, and subject of study (see Table 1). In the gender category, 65.9% of the respondents were female, and 34.1% were male. Regarding the ethnicity of the respondents, 92.8% were Han Chinese, and 7.2% were from minority groups. In terms of residence location, 58.1% of the respondents were from cities, and 41.9% were from the countryside. Pertaining to grade level, 13.6% of the respondents were freshmen, 38.9% were sophomores, 29.4% were juniors, 14.3% were seniors, and 3.8% were master’s or doctoral students. Lastly, regarding their subjects of study, 17.5% of the respondents were pursuing science subjects, 35.3% were liberal arts students, and 19.9% were in engineering disciplines.

Characteristics of the sample.

| Classification | Category | Sample number | Percentage (%) | Classification | Category | Sample number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 817 | 34.1 | Residence | City | 1372 | 58.1 |

| Female | 1580 | 65.9 | Countryside | 989 | 41.9 | ||

| Total | 2397 | 100.0 | Total | 2361 | 100.0 | ||

| Ethnicity | Han | 2225 | 92.8 | Minority Ethnicity | 172 | 7.2 | |

| Total | 2397 | 100.0 | |||||

| Education level | Freshmen | 325 | 13.6 | Subject | Science | 420 | 17.5 |

| Sophomores | 932 | 38.9 | Liberal Arts | 847 | 35.3 | ||

| Juniors | 706 | 29.4 | Engineering | 477 | 19.9 | ||

| Seniors | 344 | 14.3 | Business | 278 | 11.6 | ||

| Master’s students | 83 | 3.5 | Agriculture, Forestry, & Medicine | 130 | 5.4 | ||

| Doctoral students | 7 | 0.3 | Other disciplines | 245 | 10.2 | ||

| Total | 2397 | 100.0 | Total | 2397 | 99.9 | ||

Online knowledge acquisition (e-learning) is a continuous learning activity. Firstly, for productive knowledge acquisition, it is necessary that students have the willingness to acquire knowledge, have the motivation to pursue knowledge learning, have the perseverance to stay with autonomous learning, and have the positive willingness to improve the existing knowledge structure, all of which can help improve students’ learning ability. Secondly, knowledge acquisition behavior is an important aspect for students; such behavior comprises various knowledge learning and knowledge sharing behaviors. Knowledge sharing is the process of spreading knowledge and skills within an organization. Knowledge sharing is not the simple transfer of knowledge and information, but an important way to increase knowledge reserves and to improve the knowledge structure so as to effectively improve the ability of knowledge acquisition and to stimulate knowledge creation behavior (Bock, 2002; Senge, 1997). Finally, the effect of knowledge acquisition also needs to be evaluated (Alshaher, 2013). Through knowledge acquisition behavior, the original knowledge structure is strengthened, higher-order thinking ability is improved, and network information literacy is cultivated (Ebner et al., 2020). Online knowledge learning is a reform of the traditional knowledge acquisition mode, which requires college students to have a high level of information literacy, to treat and use electronic equipment correctly, to find means to prevent addiction and network dependence, and to learn how to use the functions of different network platforms to achieve knowledge growth (Wongwatkit, Panjaburee, Srisawasdi, & Seprum, 2020).

In terms of this study’s measurements, the respondents were to answer on a scale from “1” (indicating the lowest willingness / behavior / effect of online knowledge acquisition) to “5” (indicating the highest ones). Therefore, the variables of online knowledge acquisition were observed by using the three indicators of “knowledge acquisition willingness,” “knowledge acquisition behavior,” and “knowledge acquisition effect.”

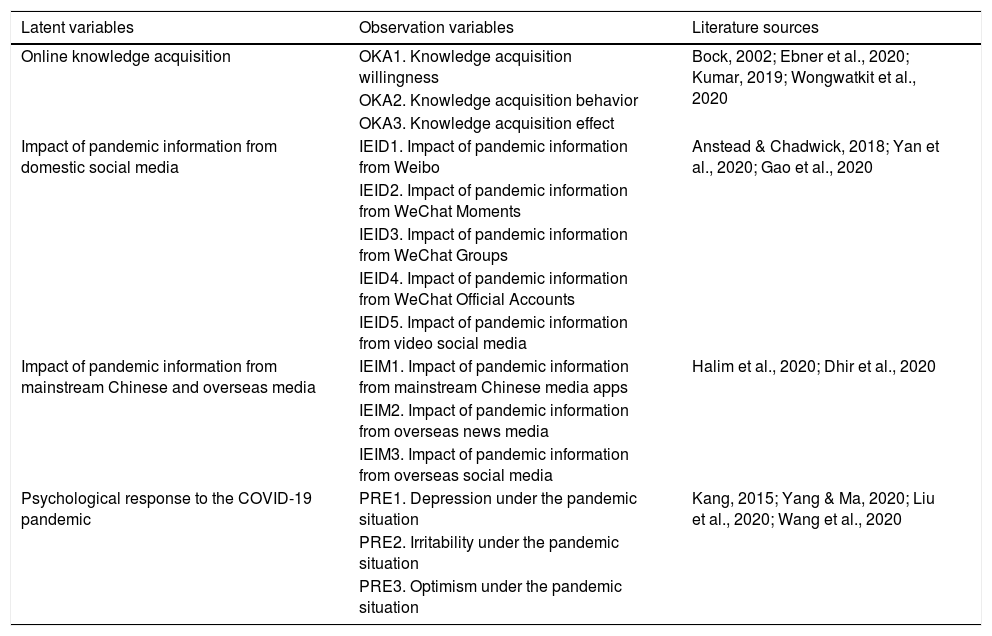

Independent variablesPandemic information of network media. In China, people generally believe that the credibility of mainstream Chinese media and overseas media is higher than that of domestic social media, although the rising trend of social media use cannot be ignored (Anstead & Chadwick, 2018; Halim et al., 2020; Valerie, 2013). Generally speaking, network information on the coronavirus pandemic has included two types: pandemic information found on domestic social media, such as Weibo, WeChat Moments, WeChat Group, WeChat Official Account, video platforms (e.g., TikTok), and so on; and pandemic information found on mainstream Chinese and overseas media, such as the People’s Daily and the BBC. Measuring the frequency of COVID-19 information obtained by the respondents through the two different types of network media was gauged on a Likert scale, from “1” (indicating “no”) to “5” (indicating “very much”) (see Table 2).

Constructs and measures.

| Latent variables | Observation variables | Literature sources |

|---|---|---|

| Online knowledge acquisition | OKA1. Knowledge acquisition willingness | Bock, 2002; Ebner et al., 2020; Kumar, 2019; Wongwatkit et al., 2020 |

| OKA2. Knowledge acquisition behavior | ||

| OKA3. Knowledge acquisition effect | ||

| Impact of pandemic information from domestic social media | IEID1. Impact of pandemic information from Weibo | Anstead & Chadwick, 2018; Yan et al., 2020; Gao et al., 2020 |

| IEID2. Impact of pandemic information from WeChat Moments | ||

| IEID3. Impact of pandemic information from WeChat Groups | ||

| IEID4. Impact of pandemic information from WeChat Official Accounts | ||

| IEID5. Impact of pandemic information from video social media | ||

| Impact of pandemic information from mainstream Chinese and overseas media | IEIM1. Impact of pandemic information from mainstream Chinese media apps | Halim et al., 2020; Dhir et al., 2020 |

| IEIM2. Impact of pandemic information from overseas news media | ||

| IEIM3. Impact of pandemic information from overseas social media | ||

| Psychological response to the COVID-19 pandemic | PRE1. Depression under the pandemic situation | Kang, 2015; Yang & Ma, 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020 |

| PRE2. Irritability under the pandemic situation | ||

| PRE3. Optimism under the pandemic situation |

Psychological response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Many college students have been getting a significant amount of COVID-19 pandemic information through network platforms and mobile apps, which has the potential to induce stress disorders (Kang et al., 2015). Because the network pandemic information impact can bring about strong psychological reactions in college students—as well as other groups—such as depression, irritability, or optimism, we followed the work of Yang and Ma (2020); Liu et al. (2020), and Ho et al. (2020) to assess these three reactions on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from “1” (indicating “no such situation”) to “5” (indicating “very serious”) (see Table 2).

Reliability and validity testingBefore performing the regression analysis, we tested the reliability and validity analysis of the questionnaire data. To gauge the reliability of the questionnaire, we used SPSS 21.0 software and examined the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. A Cronbach’s alpha value of each measured variable higher than 0.70 would suggest a relatively high reliability level. The results of this test, which are displayed in Table 2, demonstrated that the alpha values of each subscale of the questionnaire were, overall, higher than 0.7, and that the total internal consistency coefficient of the questionnaire was 0.797. This demonstrated that the reliability threshold of the questionnaire was met.

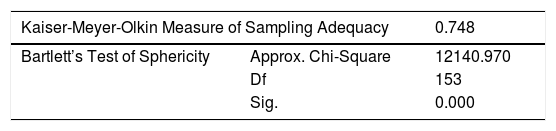

Apart from the reliability analysis, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value and the cumulative variance contribution rate were used to test the validity of the questionnaire. Generally, a KMO value equal to or greater than 0.7 and a cumulative variance contribution rate greater than 60% indicate that a questionnaire has good validity. As shown in Table 3, we found the KMO value was 0.748, thus higher than 0.7, and that the cumulative variance contribution rate was 61.388%, thus indicating that the scale had good construction validity and that the questionnaire met the test requirements.

Common method biasQuestionnaires on social problems are easily influenced by the social desirability of the respondents, which leads to the common method bias (CMB) problem. In order to minimize the impact of CMB, first, we designed simple and clear questionnaire items, we informed the respondents that the survey was anonymous, and we arranged the items to avoid the problem of the respondents’ guessing and the tendentiousness of the survey. Second, following the work of Carmona-Lavado, Gopalakrishnan, and Zhang (2020)), we controlled for CMB by using Harman’s statistical test. The results from this test showed that the largest explanation proportion of the first principal component was 22.47%—less than 50% of the total variance explained. We thus concluded that CMB was not a serious concern in this study, and that the objectivity of the survey results met the necessary requirements.

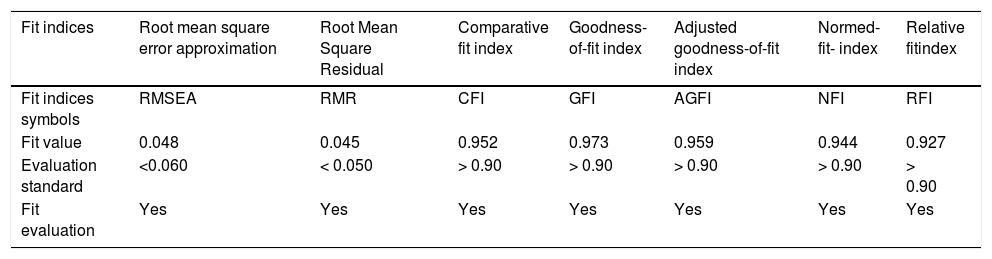

Analyses and resultsGoodness of fitWe used AMOS 26.0 software to fit the model. The model’s fit indices are shown in Table 4. The results demonstrated that the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) value was 0.048, lower than the threshold of 0.060, thus indicating an acceptable fit. Additionally, the root mean square residual (RMR) was 0.045, lower than the 0.050 threshold. Moreover, the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), the comparative fit index (CFI), the adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI), the normed fit index (NFI), and the relative fit index (RFI) were all slightly higher than the threshold value of 0.90. Overall, the fit indices indicated that the model fit the data fairly well.

The model’s fit indices.

| Fit indices | Root mean square error approximation | Root Mean Square Residual | Comparative fit index | Goodness-of-fit index | Adjusted goodness-of-fit index | Normed-fit- index | Relative fitindex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fit indices symbols | RMSEA | RMR | CFI | GFI | AGFI | NFI | RFI |

| Fit value | 0.048 | 0.045 | 0.952 | 0.973 | 0.959 | 0.944 | 0.927 |

| Evaluation standard | <0.060 | < 0.050 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 |

| Fit evaluation | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

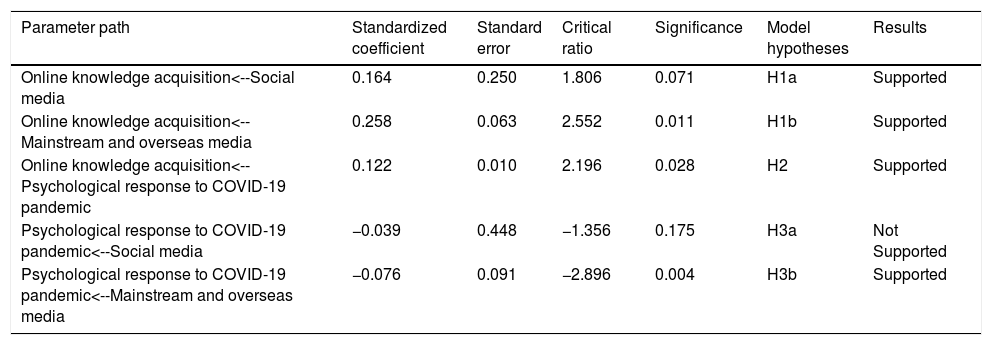

The path coefficients and the hypotheses’ verification results are given in Table 5. The results showed that the standardized path coefficient of the information impact from social media on knowledge acquisition online was 0.164, and its corresponding p-value was 0.071, indicating that the social media information impact on college students’ online knowledge acquisition was significant at the level of 10%. Therefore, H1a is supported. Moreover, the standardized path coefficient of the information impact from mainstream Chinese media and overseas media on knowledge acquisition online was 0.258, and its corresponding p-value was 0.011, lower than 0.05, indicating that the information impact from mainstream Chinese media and overseas media has had a positive role in promoting online knowledge acquisition. Therefore, H1b is supported. Compared with the social media hypothesis test, this study demonstrated that the impact of the pandemic information from mainstream Chinese media and foreign media on the online knowledge acquisition of college students was significantly higher than that of social media. We believe the reason for this is that the credibility of COVID-19 information released on social media is lower than that of mainstream Chinese and overseas media, and even that a large amount of this information on social media is meant primarily for entertainment purposes. For this reason, college students appear to be more inclined to believe the pandemic information from mainstream Chinese media and overseas media.

Path coefficients and hypotheses verification results.

| Parameter path | Standardized coefficient | Standard error | Critical ratio | Significance | Model hypotheses | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Online knowledge acquisition<--Social media | 0.164 | 0.250 | 1.806 | 0.071 | H1a | Supported |

| Online knowledge acquisition<--Mainstream and overseas media | 0.258 | 0.063 | 2.552 | 0.011 | H1b | Supported |

| Online knowledge acquisition<--Psychological response to COVID-19 pandemic | 0.122 | 0.010 | 2.196 | 0.028 | H2 | Supported |

| Psychological response to COVID-19 pandemic<--Social media | −0.039 | 0.448 | −1.356 | 0.175 | H3a | Not Supported |

| Psychological response to COVID-19 pandemic<--Mainstream and overseas media | −0.076 | 0.091 | −2.896 | 0.004 | H3b | Supported |

Moreover, the standardized path coefficient of the impact of the psychological response to the COVID-19 pandemic on online knowledge acquisition was found to be 0.122, and its corresponding p-value was 0.028, lower than 0.05, indicating that the psychological response to the pandemic situation has had a positive impact on online knowledge acquisition. Thus, H2 is supported. That is to say, the more positive and healthier the psychological response is, the better the performance (i.e., willingness, behavior, and effect) of college students to acquire knowledge online.

We also tested the direct effect of the two general kinds of network media on the college students’ psychological response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The results showed that the standardized coefficient of the information impact of mainstream Chinese and overseas media on the psychological response to the COVID-19 pandemic was -0.076, and that the corresponding p-value was 0.004, less than 0.05, thus indicating that the information impact of Chinese mainstream media and overseas media has had a significant negative impact on the psychology of college students. In other words, the more information college students obtain about the COVID-19 pandemic situation from mainstream Chinese media and overseas media, the lower their mental health, and the more likely they are to have negative emotions, such as depression and irritability. Moreover, the test results also demonstrated that the standardized coefficient of social media information on the psychological response to the COVID-19 pandemic was -0.039, but that its corresponding p-value was 0.175, which is greater than 0.05. This indicates that the impact of social media information on the negative psychological reaction of college students was not significant, and there was no direct statistical effect between them.

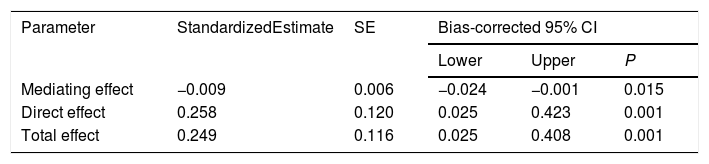

Mediating effect testAccording to Baron and Kenny (1986), it is only when three specific conditions are satisfied that researchers should perform a mediating effect test: (a) when the independent variables significantly affect the mediating variables and the dependent variables, (b) when the mediating variables significantly affect the dependent variables, and (c) when after the first two conditions have been satisfied, the relationship between the independent variables and the dependent variables changes with the intervention of the intermediary variables. If the direct effect of standardization is not significant, it is regarded as a complete intermediary; on the other hand, if the direct effect of standardization is less than the total effect of standardization, it is a partial intermediary (Baron & Kenny, 1986).

According to the results of this study, the influence of social media information on the mediating variable (i.e., the psychological response to the COVID-19 pandemic) was found to be not significant, so there was no condition to test the mediating effect. The influence of mainstream Chinese media and foreign media on the mediating variables and the dependent variables were significant and did meet the other two conditions. Therefore, we examined whether college students’ psychological response to the COVID-19 pandemic has had a mediating effect on the relationship between the independent variable (i.e., the impact of the pandemic information from mainstream Chinese media and overseas media) and the dependent variable (i.e., college students’ online knowledge acquisition).

In this study, we used the bootstrap function to conduct 5000 repetitions of sampling, and constructed a 95% error correction confidence interval. When the upper and lower limits of the confidence interval do not include a “0.” then the mediating effect is proved. In this work, the test results showed that the mediation effect was -0.009, that the lower limit of the 95% confidence interval after error correction was -0.024, that the upper limit was -0.001, and that the middle did not contain a “0.” Additionally, the corresponding p-value was 0.015, which is less than 0.05, which verifies the existence of an intermediary effect. The results showed that the psychological reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic has had a mediating effect in the relationship between the information impact from mainstream Chinese media and foreign media on the online knowledge acquisition of college students, and that this mediating effect was negative. Thus, H3a is supported. That is, when college students have been impacted more by mainstream Chinese and overseas media information, they have had a greater psychological burden, and thus, this has weakened their willingness and behavior to acquire online knowledge. The results of the bootstrap test also showed that the standardized direct effect was 0.258, that the lower limit of the 95% confidence interval after error correction was 0.025 and that the upper limit was 0.423. The corresponding p-value was found to be 0.001, which is less than 0.05, indicating that there was a direct effect (see Table 6). This conclusion is consistent with the previous direct effect test.

Discussion and conclusionsDiscussion and contributionsUsing a sample of 2397 college students in the COVID-19 pandemic era, we examined the information impact of the COVID-19 pandemic from media on college students’ online knowledge acquisition. Our findings contribute to the existing literature in three key respects.

First, the influence of pandemic information from mainstream Chinese media and overseas media on college students’ online knowledge acquisition was found to be significantly higher than that of social media. In view of this, it is particularly important to improve the professional quality and media ethics of mainstream media. On the one hand, in the spirit of social responsibility, mainstream media companies urgently need to cultivate better media literacy and Internet thinking capability and become an authoritative voice, rather than a tool for spreading rumors (Zarocosta, 2020). On the other hand, the government and the media should strengthen the dispersal of information and provide more education on the pandemic situation so that college students and others can look at the pandemic situation more scientifically and rationally. During the time of COVID-19, the interaction spaces of WeChat and other new media can produce emotional imbalance or loss of self. In the post-pandemic era, it is crucial that we should adjust, conduct information guidance and network governance, and pay attention to the core value of living healthy lives (Ho et al., 2020).

Second, our research showed that the impact of pandemic information from mainstream Chinese and overseas media had a significant negative impact on college students’ psychology. When the pandemic information from mainstream Chinese media and foreign media was greater, the worse the mental health of college students was found to be, the more likely the students were to have negative emotions like depression and irritability, which, in turn, could affect their online knowledge acquisition (Elhai et al., 2020; Haider & Al-Salman, 2020). Because of this situation, we should guide college students to cultivate positive emotions and psychological adjustments in order to eliminate adverse psychological reactions and to strengthen prevention mechanisms to guard against psychological crises (Larry, Phoenix, & Han, 2019), as well as to stimulate college students’ feelings of social responsibility.

Third, this study showed that the more positive and the healthier the psychological responses to the COVID-19 pandemic situation were, the stronger the willingness of college students to acquire knowledge by online means and the better the effect of acquiring that knowledge (Dhawan, 2020). The essence of online learning is a process of social interaction, constructiveness, self-regulation, and reflection, which can help learners maintain physical and mental health, establish crisis awareness, strengthen self-planning and self-management, improve learning concentration, and realize deep-seated learning (Kumar, 2019; Sun & Su, 2020). Furthermore, college students should seek to establish social relationships online where they can share valuable information and obtain more knowledge from others (Ghahtarani, Sheikhmohammady, & Rostami, 2020; Razak, Pangil, Zin, Yunus, & Asnawi, 2016).

Managerial implicationsOur results offer some significant managerial implications for media firms, governments, and college students in the COVID-19 pandemic era. First, it is important to increase the hardware support for college students’ knowledge acquisition. Here, organizations could optimize online learning tools, such as “cloud notes,” social software, interactive software, and visual mind maps. Additionally, in order to reduce the cognitive load, organizations could cultivate computational thinking and intelligent thinking, provide guarantees to college students to achieve knowledge acquisition by using new methods and new hardware, and find novel ways stimulate the students’ internal drive to pursue online learning (Xie, Wang, & Zeng, 2018; Xie, Zou, & Qi, 2018; Caseiro & Coelho, 2019).

Second, enterprises and governments should increase technical support for online learning and knowledge accumulation. As a new type of enterprise in the Internet era, they should vigorously develop new technologies, such as 5th-generation (5 G) mobile networks, artificial intelligence (AI), and the Internet of things; improve the capabilities of human-computer collaboration and the role of business networks for innovation (Damian & Manea, 2019; Höflinger, Nagel, & Sandner, 2018; Lee & Trimi, 2018; Öberg, 2019); and provide technical support for sustainable knowledge learning (Xie, Xie, & Martinez-Climent, 2019). As digital natives, college students should adapt to the changes of online learning technology, improve their computer self-efficacy, and continually strive to improve their ability to acquire knowledge by using diverse network tools.

Third, the government should push the media and college students to construct the social value of knowledge learning in the openness of the Internet. In the era of network media, great changes have taken place in terms of knowledge transmission and knowledge sharing. Meanwhile, network media should construct the network ethics of the new era and be a leader in shaping the social value of the Internet. Lastly, for their part, the younger generation should use the “knowledge feedback” channel to help the elderly and to cooperate with their elders to increase new knowledge acquisition in the Internet era.

Limitations and further researchThere were some limitations in this study that should be considered in future research. On the one hand, our empirical results were derived from a sample of Chinese college students, and therefore our findings might be country-specific. Future research could use samples from other countries to test and extend this research. On the other hand, the COVID-19 pandemic is a novel global challenge, and thus, there is no mature scale for reference in the research. Although the questionnaire design of this study drew lessons from previous research, we acknowledge that there were still many deficiencies. In view of this, it is clear that future research will further deepen and improve our understanding of this subject.

This research was sponsored by the Major projects of National Social Science Fund (Grant No. 20ZDA065), the projects of National Social Science Fund (Grant No. 20BXW048), the General Project of Shanghai philosophy and Social Science Planning Foundation (Grant No. 2019CGL100), and Shanghai Shuguang Program (Grant NO. 19SG20).

Xuefang Xie is currently a professor at School of Humanities, Tongji University, China. Her research interests include cultural innovation and creative industries. She has published over 100 articles in major refereed journals in cultural and creative industries.

Zhipeng Zang is currently a professor at School of Communication, Director of Cultural Industry Research Institute, East China University of Political Science and Law. His research interests include cultural and creative industry management and corporate governance. He has published well four academic books, and published over 50 articles both in International and China’s journals, such as Industry and Innovation, Journal of Cleaner Production, Chinese Management Studies, among others.

José M. Ponzoa is currently a professor at Business & Marketing School, ESIC University. His research interests include digital transformation, innovation and economics. He has published academic books, and articles both in International and Spain’s journals, such as Technological Forecasting & Social Change, among others.