This article investigates the critical role of Digital Literacy (DL) in shaping the adoption and use of ChatGPT. As advanced AI tools rapidly integrate into daily life, it is essential for both policymakers and technology developers to understand the factors driving their mainstream adoption. DL was quantified using the Internet Skills Scale (ISS) tool, applied on a scale of 0 to 10 across six areas of ChatGPT application: general use, testing possibilities, entertainment, fulfilling work and school tasks, obtaining new knowledge, and companionship during moments of solitude. The study employs non-parametric difference tests, relational analyses, and binomial logistic regression models, analysing data from a statistically representative sample (N = 1,025) of the Czech population. The findings reveal significant relationships between DL and five of the six areas. Higher DL levels correlate with using ChatGPT for testing, entertainment, and acquiring new knowledge. Conversely, lower DL levels are linked to using ChatGPT as a companion during moments of solitude. Notably, no significant relationship was found between DL and using ChatGPT for work or educational purposes. These results suggest that as DL improves, the use of AI tools like ChatGPT will diversify across different contexts. The study highlights the need for targeted DL programs to enhance AI adoption, reduce digital inequalities, and ensure that advanced technologies are accessible to all population segments.

Digital literacy (DL) encompasses a broad range of educational practices aimed at equipping users with the knowledge and skills required to effectively operate within digital societies. Some studies integrate media and information literacy within the scope of DL; however, defining the exact boundaries and intersections of these concepts requires further research (Wuyckens, Landry & Fastrez, 2022). Each literacy type has its own limitations. For example, media literacy often overlooks the specific characteristics of digital technology and its role in enabling new communication practices. In contrast, information literacy has been criticised for its lack of emphasis on developing a critical perspective, a strength typically associated with media literacy (Leaning, 2019). The evolution of digital skills is closely tied to emerging technologies, such as cloud computing, the Internet of Things (IoT), big data, AI, and robotics. Numerous studies have highlighted significant regional disparities in DL linked to differences in digital skills, access, usage, and self-perception (Hamutoglu, Gemikonakli, De Raffaele & Gezgin, 2020; Tinmaz, Lee & Fanea-Ivanovici, 2022). Although physical access to digital technologies is often cited as a factor in digital inequalities, the more pressing issue is the gap in digital skills (Van Deursen & Van Dijk, 2010).

Expertise and scientific literature on DL present a wide array of definitions that incorporate various technical and nontechnical elements. This diversity complicates efforts to create unified comparison platforms and often results in definitional frameworks in which certain aspects are disproportionately emphasised, leading to biases and limitations in assessment systems, particularly across different population groups. DL concepts have evolved along with technological advancements, with each period giving rise to new frameworks. For example, Eshet-Alkalai (2012) identified six DL categories: photovisual, real-time, informational, branching, reproductive, and social-emotional thinking. In contrast, Heitin (2016) simplified DL into three clusters: searching for and consuming digital content, creating digital content, and communicating or sharing digital content. Tinmaz, Lee and Fanea-Ivanovici (2022) expand the scope of DL to include computer, media, cultural, and disciplinary literacy. Policy-making bodies such as the European Commission have also weighed in to develop a framework comprising five competence areas: information and data literacy, communication and collaboration, digital content creation, security, and problem-solving. The framework is currently being reviewed and updated. Critics have emerged alongside these developments; for instance, Weninger (2023) argues that the predominant focus on DL skills overlooks its broader implications, advocating for DL to be developed as a social practice.

The development and introduction of new AI tools have introduced new demands on DL as well as digital skills and competencies. As AI tools are integrated into daily life, there is an increasing need for individuals to acquire digital skills (Vasilescu, Serban, Dimian, Aceleanu & Picatoste, 2020). The level of these skills is influenced not only by technological experience and adoption, but also by the underlying reasons for using these tools, which reveal user motivations and preferred trajectories for AI tool utilisation. Analysing these preferences can reveal a tool's potential for assessing DL and its capacity to enhance various DL components, such as information navigation, content creation, social interactions, and mobile device usage. Currently, no research has explored the links between the intention to use AI tools in specific fields and DL, as measured using the Internet Skills Scale (ISS) (Van Deursen, Helsper & Eynon, 2016). Our study focused on one of the latest AI tools, ChatGPT, a conversational AI model developed by OpenAI. Since the release of its latest version, GPT-4, in March 2023, this tool has garnered significant attention across various domains. The potential of ChatGPT to revolutionise communication and information sharing emphasises the pressing need to address digital inequality. Its existence highlights disparities in access to technology and DL (Khan & Paliwal, 2023).

Investigating the relationship between DL, as measured by the ISS, and ChatGPT usage can help identify how DL influences the intention to use this tool for various purposes. This analysis provides insights into how different dimensions of DL contribute to the adoption of ChatGPT, thereby guiding the further development of DL in relation to specific AI tools. Understanding these connections is crucial for tailoring DL programs and ensuring that users are equipped with the necessary skills to effectively use advanced technologies, such as ChatGPT. This study was motivated by the need to explore and quantify the links between DL and the use of AI tools such as ChatGPT. Our primary goal was to identify the preferred trajectories for ChatGPT usage and uncover the potential for the further development of DL concepts. The lack of research on the relationship between AI tool usage intentions and various DL fields has hindered the progress of DL and formulation of effective educational, digital, and development policies.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews existing maturity or readiness models in the relevant domain and outlines our research contributions. Section 3 describes our concepts of organizational maturity and the framework used to develop the Industry 4.0 Maturity Model. In Section 4, we present the resulting model and procedure for assessing the maturity. Section 5 discusses the preliminary findings of a case study conducted at a manufacturing company. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper with the main findings, study limitations, and suggestions for future research.

Literature reviewDL has been explored in numerous studies, each examining it from different process-based, structural, and causal perspectives. To understand the connections among these perspectives, it is crucial to investigate the conceptual relationships of DL within a broader digital ecosystem. In line with our study's aim of quantifying the relationship between DL and specific fields of ChatGPT usage, we also examined the definitional and adoption potential of ChatGPT, along with the motivational factors driving its use. This comprehensive approach provides a deeper understanding of how DL interacts with emerging AI tools and strategies to enhance its application in diverse contexts.

Digital literacy and its conceptual connectionsThe rapid pace of digital transformation has been significantly influenced by the development of DL (Gillter, 1997). Conceptually aligned with AI literacy, DL plays a transformative role in society, enhancing competencies across various sectors, such as education, banking, healthcare, trade, industry, and services, which are areas closely tied to quality of life (Lingyan, Mawenge, Rani & Patil, 2021). Digital interaction has become increasingly important in the context of DL (Reddy, Sharma & Chaudhary, 2020), and some scholars view it as an essential tool for navigating a digital society (Koc & Barut, 2016). The impact of the social environment on digital transformation processes has highlighted the importance of the emotional, social, and ethical aspects of DL (Koc & Barut, 2016; Lee & Bae, 2023). In addition to digital interaction, DL influences digital content consumption. Media literacy, viewed by some as an integral part of DL or its more advanced form, has developed significantly over the past decade (Park, Kim & Park, 2021). Koc and Barut (2016) categorised media literacy into four dimensions: functional consumption, critical consumption, functional assumptions, and critical prerequisites. They also emphasised the need for active production skills in new media literacy, including the creation and co-creation of digital artefacts. Lee and Park (2024) propose examining five ChatGPT literacy factors: technical ability, critical evaluation, communication abilities, creative application, and ethical competence, including physical and social factors (Laupichler et al., 2024; Lee, Bubeck & Petro, 2023; Park et al., 2023).

Scholars have linked the digital environment to the necessity of information literacy. For instance, Nikitenko, Voronkova and Kaganov (2024) emphasised the critical role of information literacy in survival in the digital world, advocating for intercultural, systemic, structural-functional, institutional, anthropological, and axiological approaches to enhance digital competencies. The preference for linking information literacy or DL to the digital environment depends on whether the focus is on the developmental, procedural, or structural aspects of the digital ecosystem. The evolution of DL is closely tied to the emergence of new AI tools, which in turn influence its trajectory and intensity. The development of ChatGPT, for instance, does not occur in isolation but in conjunction with other tools, generating synergistic effects within digitisation processes. While this synergy has the potential to benefit users, it also introduces risks (Khan, 2023), such as increasing opacity in processes where AI tools are applied. Zhao et al. (2024) highlighted that generative AI tools such as ChatGPT significantly impact educational processes, not only in writing but also in information acquisition and problem-solving. However, the current criticism of these tools mainly revolves around issues such as plagiarism, misinformation, and technological dependence (Adeshola & Adepoju, 2023). Thus, the risk analysis of AI tools is essential for developing defensive strategies tailored to each generative AI application. This requires a multidisciplinary approach and the sharing of experiences with each tool in specific applications. Ethical concerns are also a significant aspect of AI tool usage (Hua, Jin & Jiang, 2024), yet recent studies have shown that ethical issues are often poorly understood or inadequately addressed.

Several scholars have employed the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) model to elucidate user behaviour regarding technology adoption (Chao, 2019). However, extensive socioeconomic, technological, and psychological research indicates that the adoption and utilisation of these tools are dynamic processes influenced by emerging factors such as perceived security, trust and privacy, perceived enjoyment, and system interactivity. These elements collectively form a complex framework for understanding user behaviour (Menon & Shilpa, 2023). Among these, perceived interactivity, which encompasses sensitivity, flexibility, and support for two-way communication between the user and the AI tool, is often highlighted as a dominant factor. In addition, attributes such as perceived human touch (Della Longa, Valori & Farroni, 2022; Van Erp & Toet, 2015), humour, and empathy are gaining prominence. Perceived human touch pertains to the social presence and emotional connection individuals experience during interactions, whether through touch, vocal cues, or eye contact (McIntyre, Hauser & Kusztor, 2022). The promptness of responses also plays a crucial role in the positive perception of AI tools because it enhances productivity. Currently, the demand for AI tools is driven more by the quality of answers than their quantity (Kim, Kim, Kim & Park, 2023). Concurrently, expectations for the accuracy, correctness, and relevance of information are increasing. In specialised fields, such as healthcare, there may be specific requirements for responses, such as brevity and precision.

Definition and potential for adoption of ChatGPTNumerous studies have demonstrated how ChatGPT enhances task performance, leading to the development of sector-specific adaptation frameworks for this tool (Mogaji, Balakrishnan, Nwoba & Nguyen, 2021). Menon and Shilpa (2023) applied the UTAUT model to identify key factors that influence ChatGPT adoption and use, noting that user interaction and engagement are shaped by perceived interactivity and privacy concerns. Additionally, age and experience can moderate the impact of these factors on ChatGPT usage and increase expectations and demand for the tool (Camilleri, 2024; Choudhury & Shamszare, 2024). The effectiveness of the UTAUT model in conceptualising ChatGPT can be linked to perceptions of performance expectancy and usefulness (Venkatesh, Morris, Davis & Davis, 2003). Expected performance is associated with perceived usefulness, compatibility, the chatbot's impact on work performance, task completion, feelings of success, and increased engagement (Brachten, Kissmer & Stieglitz, 2021; Christy et al., 2019). According to Yang and Wang (2023), perceived risk, trust, and demand satisfaction are the most critical factors for the public adoption of ChatGPT. Perceived risk and trust directly influence public acceptance, whereas factors such as supervision and accountability play a significant role in exerting a powerful driving force on overall acceptance.

The expected length of the effort is a significant factor in ChatGPT adoption (Jain et al., 2024). Users anticipate that a new technology should be simple to adopt and use quickly, with perceived simplicity directly influencing their likelihood of adopting it (Tiwari, Bhat, Khan, Subramaniam & Khan, 2024). Research on the impact of expected effort on chatbot adoption has yielded contrasting results. While Henkel, Linn and van der Goot (2022) found a negative relationship between expected effort and intention to use chatbots, sector-specific analyses showed that expected effort plays a crucial role in chatbot adoption (Mogaji et al., 2021). If users perceive ChatGPT as easy to use, they are more likely to integrate it into their daily lives, potentially leading to its widespread adoption across various fields and an increase in the value of the technology. User perceptions of the usefulness and simplicity can also enhance the positive social impact of ChatGPTs. Social influences, ranging from family and friends to online opinions and expert recommendations, can further bolster users’ confidence in using ChatGPT effectively, reducing barriers to adoption and perceived risks (Menon & Shilpa, 2023).

Wulandari, Nurhaipah and Ohorella (2024) found that social influence does not significantly affect the perceived simplicity of user experience. Negative social impacts such as concerns about the potential misuse of ChatGPT, ranging from harmful or biased content to the spread of disinformation and ethical issues, can increase reliability concerns and strengthen user resistance, thereby diminishing adoption potential (Sudan, Hans & Taggar, 2024). The social impact of ChatGPT needs to be explored both horizontally and vertically, as different population groups with varying experiences, attitudes toward technology, and levels of DL may exert diverse influences on different social groups. This complexity necessitates a more in-depth analysis to understand the broader social implications of using ChatGPT.

Motivational aspects of ChatGPT useThe conditions supporting ChatGPT adaptation encompass both technical and organizational infrastructures. Combined with positive social impact and perceived usefulness, these factors can significantly accelerate ChatGPT adoption. However, technical issues or lack of access to the necessary technological resources can create aversion and resistance to change. Sociodemographic factors are closely linked to perceived difficulty and trust (Hasija & Esper, 2022). Research indicates that age and sex positively influence the perceived usefulness and user intention to adopt ChatGPT. For instance, older adults may find ChatGPT more challenging or less valuable, while those with prior technological experience may perceive it as more user-friendly and beneficial (Menon & Shilpa, 2023). Additionally, risk perception varies with experience and age categories (Valtolina, Matamoros, Musiu, Epifania & Villa, 2022). Overreliance on ChatGPT could lead to feelings of inferiority as users limit social interaction, potentially weakening critical thinking and problem-solving abilities in daily life (Shanto, Ahmed & Jony, 2024).

Research has demonstrated a clear relationship between socio-demographic characteristics and the use of AI tools, with education and age being particularly influential in AI adoption. For example, Wu and Shi (2024) found that increasing DL among university students significantly shaped their perception of ChatGPT's usefulness and ease of use, thereby boosting their intention to use the tool. AI solutions enhance the efficiency and sustainability of blended learning systems, improve access to education, and foster inclusivity (Alshahrani, 2023). Moreover, ChatGPT can help alleviate loneliness, especially among the elderly, by fostering emotional connections, although it should complement rather than replace human interactions (Pani et al., 2024). Skjuve et al. (2024) identified six key motivations for using ChatGPT: productivity, novelty, creative work, learning and development, entertainment, and social interaction. These findings suggest that generative AI can satisfy various user needs, surpassing traditional conversational technologies. While some studies highlight ChatGPT's role in enhancing creativity and reducing costs (Skjuve, Følstad, Fostervold & Brandtzaeg, 2022), others, such as Shidiq (2023), warn of its potential negative impact on creativity in education, particularly in student writing. Nonetheless, ChatGPT can still enhance learning experiences and promoted independence.

Some users engage in ChatGPT for entertainment and social interaction (Gorenz & Schwarz, 2024; Thorp, 2023), while it can also serve as a valuable tool for disadvantaged groups. It assists individuals with autism in solving everyday problems by acting as a robust information-seeking tool (Choi et al., 2024). AI, including ChatGPT, plays a transformative role in enhancing decision-making even though it does not directly make decisions (Sundar & Liao, 2023). However, overreliance on ChatGPT can lead to excessive trust in its outcomes, potentially resulting in bias, misuse, reduced quality, or the spread of disinformation (Sebastian & Sebastian, 2023). The use of ChatGPT varies significantly in professional settings, depending on the individual user, and there remains a research gap concerning AI chatbots from an employee's perspective (George & George, 2023; Iswahyudi, Nofirman, Wirayasa, Suharni & Soegiarto, 2023). Methodologies, such as inductive taxonomies, can be employed to better understand user interactions with ChatGPT. Nickerson, Varshney and Muntermann (2013) identified four types of ChatGPT users: early quitters, progressives, pragmatics, and persistent users, categorizing user perceptions into tools and virtual personal assistants (Gkinko & Elbanna, 2023). Another framework by Capello and Lenzi (2023) distinguishes between technological enthusiasts, who see strong potential in new technologies, and technological pessimists, who fear catastrophic consequences, social disruption, and the loss of labour opportunities.

Ilieska (2024) argues that generative AI tools, such as ChatGPT, pose a potential threat to human cognitive autonomy, flagging the need for renewed efforts to cultivate critical thinking. She cautions against the dangers of thoughtlessness in an age of rapid scientific progress, emphasising that thinking is a unique human capability that must be protected by fostering spaces for genuine reflection and engagement. Gkinko and Elbanna (2023) applied the technological framing theory to explore how disparities in employees' technological perspectives impact chatbot use. Their findings suggest that consensus within organizational technological frameworks promotes the adoption and effective use of technology, whereas disagreements can hinder technological integration and reduce efficiency. Several studies have explored the root causes of these disparities and have proposed solutions to address them (Khalil, Dai, Zhang, Dilkina & Song, 2017; Wei et al., 2024; Xie, Zhao, Deng & He, 2024).

ChatGPT is increasingly applied in sophisticated ways across various industries, from education to entertainment, and in research. Researchers are gradually focusing on the social and cultural impacts of ChatGPT use. One of the most challenging aspects of natural language processing is understanding the subtleties and complexities of human language, including humour, irony, and sarcasm (Reswan Shihab, Sultana & Samad, 2023). The limited capacity of ChatGPT to fully grasp and respond to these elements can lead to inappropriate or irrelevant answers. Another challenge to the broader adoption of ChatGPT lies in its resource requirements. The model requires significant computing power, and its initiation can be particularly constrained in resource-limited environments.

Consequently, six research hypotheses were formulated to align with our study's objectives:

H1

There is a significant relationship between the intention to use ChatGPT and DL, as measured by the Internet Skills Scale (ISS).

H2

The intention to use ChatGPT to test its capabilities is significantly related to DL, as measured by the ISS.

H3

The intention to use ChatGPT for entertainment purposes is significantly related to DL, as measured by the ISS.

H4

The intention to use ChatGPT for educational or work purposes is significantly related to DL, as measured by the ISS.

H5

The intention to use ChatGPT to gain new knowledge is significantly related to DL, as measured by the ISS.

H6

The intention to use ChatGPT as a companion during solitary time is significantly related to DL, as measured by the ISS.

Material and methodsTo address the research goal of examining and quantifying the relationship between DL and selected fields of AI as represented by ChatGPT, a comprehensive study design was developed with a solid methodological foundation.

The research questions were formulated based on the latest findings and outcomes of this study. Given the extensive body of research on DL, we focused on tools that have been successfully applied in similar empirical studies, allowing us to assess their effectiveness and limitations. For our methodology, we selected the digital literacy evaluation tool used by Van Deursen et al. (2016), which incorporates a validated set of Internet Skills Scale (ISS) items. This tool was chosen because of its robustness and applicability in similar research contexts to ensure the reliability of our findings.

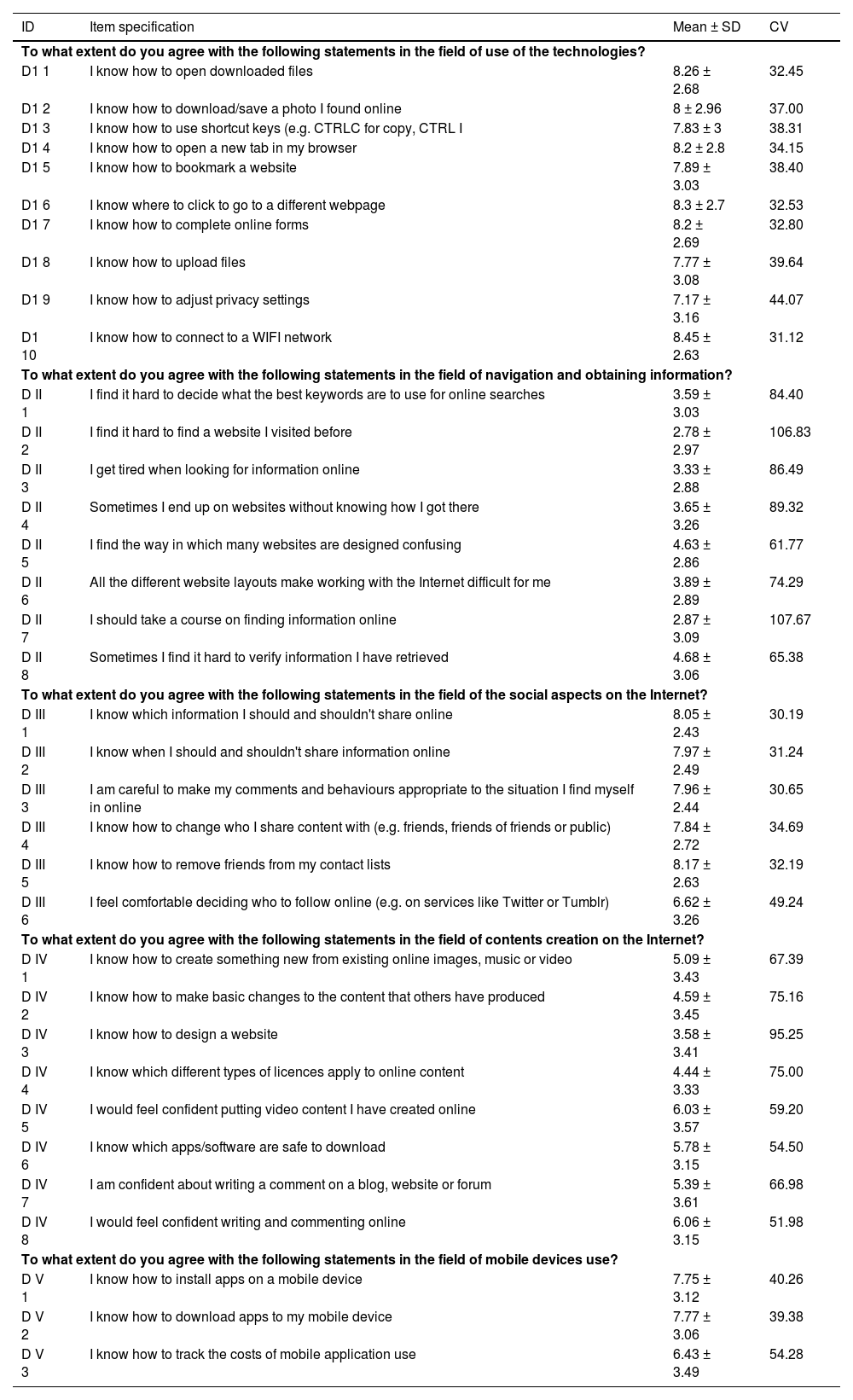

The study processed 35 items categorised into five distinct factors using the DL evaluation tool as follows (Table 1):

- i.

Operational: To what extent do you agree with the following statements regarding technology use?

- ii.

Information Navigation: To what extent do you agree with the following statements that focus on navigating and obtaining information on the Internet?

- iii.

Social: To what extent do you agree with the following statements that focus on the social aspect of the Internet?

- iv.

Creative: To what extent do you agree with the following statements that focus on creating content on the Internet?

- v.

Mobile: To what extent do you agree with the following statements that focus on the use of mobile devices?

D variables description - population DL (ISS).

| ID | Item specification | Mean ± SD | CV |

|---|---|---|---|

| To what extent do you agree with the following statements in the field of use of the technologies? | |||

| D1 1 | I know how to open downloaded files | 8.26 ± 2.68 | 32.45 |

| D1 2 | I know how to download/save a photo I found online | 8 ± 2.96 | 37.00 |

| D1 3 | I know how to use shortcut keys (e.g. CTRLC for copy, CTRL I | 7.83 ± 3 | 38.31 |

| D1 4 | I know how to open a new tab in my browser | 8.2 ± 2.8 | 34.15 |

| D1 5 | I know how to bookmark a website | 7.89 ± 3.03 | 38.40 |

| D1 6 | I know where to click to go to a different webpage | 8.3 ± 2.7 | 32.53 |

| D1 7 | I know how to complete online forms | 8.2 ± 2.69 | 32.80 |

| D1 8 | I know how to upload files | 7.77 ± 3.08 | 39.64 |

| D1 9 | I know how to adjust privacy settings | 7.17 ± 3.16 | 44.07 |

| D1 10 | I know how to connect to a WIFI network | 8.45 ± 2.63 | 31.12 |

| To what extent do you agree with the following statements in the field of navigation and obtaining information? | |||

| D II 1 | I find it hard to decide what the best keywords are to use for online searches | 3.59 ± 3.03 | 84.40 |

| D II 2 | I find it hard to find a website I visited before | 2.78 ± 2.97 | 106.83 |

| D II 3 | I get tired when looking for information online | 3.33 ± 2.88 | 86.49 |

| D II 4 | Sometimes I end up on websites without knowing how I got there | 3.65 ± 3.26 | 89.32 |

| D II 5 | I find the way in which many websites are designed confusing | 4.63 ± 2.86 | 61.77 |

| D II 6 | All the different website layouts make working with the Internet difficult for me | 3.89 ± 2.89 | 74.29 |

| D II 7 | I should take a course on finding information online | 2.87 ± 3.09 | 107.67 |

| D II 8 | Sometimes I find it hard to verify information I have retrieved | 4.68 ± 3.06 | 65.38 |

| To what extent do you agree with the following statements in the field of the social aspects on the Internet? | |||

| D III 1 | I know which information I should and shouldn't share online | 8.05 ± 2.43 | 30.19 |

| D III 2 | I know when I should and shouldn't share information online | 7.97 ± 2.49 | 31.24 |

| D III 3 | I am careful to make my comments and behaviours appropriate to the situation I find myself in online | 7.96 ± 2.44 | 30.65 |

| D III 4 | I know how to change who I share content with (e.g. friends, friends of friends or public) | 7.84 ± 2.72 | 34.69 |

| D III 5 | I know how to remove friends from my contact lists | 8.17 ± 2.63 | 32.19 |

| D III 6 | I feel comfortable deciding who to follow online (e.g. on services like Twitter or Tumblr) | 6.62 ± 3.26 | 49.24 |

| To what extent do you agree with the following statements in the field of contents creation on the Internet? | |||

| D IV 1 | I know how to create something new from existing online images, music or video | 5.09 ± 3.43 | 67.39 |

| D IV 2 | I know how to make basic changes to the content that others have produced | 4.59 ± 3.45 | 75.16 |

| D IV 3 | I know how to design a website | 3.58 ± 3.41 | 95.25 |

| D IV 4 | I know which different types of licences apply to online content | 4.44 ± 3.33 | 75.00 |

| D IV 5 | I would feel confident putting video content I have created online | 6.03 ± 3.57 | 59.20 |

| D IV 6 | I know which apps/software are safe to download | 5.78 ± 3.15 | 54.50 |

| D IV 7 | I am confident about writing a comment on a blog, website or forum | 5.39 ± 3.61 | 66.98 |

| D IV 8 | I would feel confident writing and commenting online | 6.06 ± 3.15 | 51.98 |

| To what extent do you agree with the following statements in the field of mobile devices use? | |||

| D V 1 | I know how to install apps on a mobile device | 7.75 ± 3.12 | 40.26 |

| D V 2 | I know how to download apps to my mobile device | 7.77 ± 3.06 | 39.38 |

| D V 3 | I know how to track the costs of mobile application use | 6.43 ± 3.49 | 54.28 |

Table 1 presents the DL indicators, each evaluated on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 indicates complete disagreement with the statement, and 10 signifies complete agreement. Respondents were required to answer all items, and no filtering was applied. Consequently, no missing values were observed in the dataset. The survey yielded 1025 responses and was conducted between 19 October 2023 and 1 November 2023. Data were collected using a ((computer-assisted self-interview) technique via the Ipsos online panel Populace.cz.

Table 2 presents the frequency distributions of the samples across the selected identification variables. The data indicate that the sample was proportionally balanced, although there was a slight underrepresentation of students in the Family Lifecycle Segment category compared to the general population. This minor deviation was not expected to significantly affect the validity or reliability of the study outcomes.

Research sample description.

| ID var | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 519 | 50.6 |

| Female | 506 | 49.4 |

| Age | ||

| 18 - 24 | 68 | 6.6 |

| 25 - 34 | 158 | 15.4 |

| 35 - 44 | 177 | 17.3 |

| 45 - 54 | 170 | 16.6 |

| 55 - 65 | 170 | 16.6 |

| 66 - 99 | 282 | 27.5 |

| Municipality population | ||

| Up to 1000 inhabitants | 157 | 15.3 |

| 1001 to 5000 inhabitants | 192 | 18.7 |

| 5001 to 20,000 inhabitants | 169 | 16.5 |

| 20,001 to 100,000 inhabitants | 266 | 26.0 |

| over 100,000 inhabitants | 241 | 23.5 |

| Education | ||

| Primary and secondary without diploma | 451 | 44.0 |

| Secondary with diploma | 341 | 33.3 |

| Tertiary | 233 | 22.7 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married, living with a partner, | 600 | 58.5 |

| Widowed | 58 | 5.7 |

| Divorced | 150 | 14.6 |

| Single | 217 | 21.2 |

| Segment Family Lifecycle | ||

| STUDENT | 22 | 2.1 |

| SINGLES & DINKIES | 171 | 16.7 |

| YOUNG FAMILIES | 206 | 20.1 |

| ELDER FAMILIES | 107 | 10.4 |

| EMPTY NESTERS | 222 | 21.7 |

| SILVER AGE | 277 | 27.0 |

| Others | 20 | 2.0 |

Note: Total = 1025.

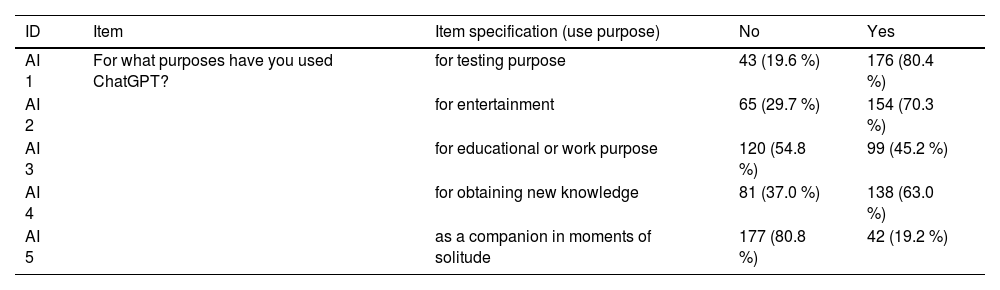

Table 3 details the frequency of responses related to specific uses of AI, particularly ChatGPT. The ‘Yes’ category indicates respondents who utilized ChatGPT for the specified purpose, while the ‘No’ category reflects those who did not. The table includes only those respondents who answered affirmatively to the question, ‘Have you tried how ChatGPT works?’ - indicating prior experience with the AI tool. Out of the total sample, 219 respondents, or 21.37%, reported having used ChatGPT. This suggests that approximately one-fifth of the population in the sample has direct experience with ChatGPT.

AI variables description.

| ID | Item | Item specification (use purpose) | No | Yes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI 1 | For what purposes have you used ChatGPT? | for testing purpose | 43 (19.6 %) | 176 (80.4 %) |

| AI 2 | for entertainment | 65 (29.7 %) | 154 (70.3 %) | |

| AI 3 | for educational or work purpose | 120 (54.8 %) | 99 (45.2 %) | |

| AI 4 | for obtaining new knowledge | 81 (37.0 %) | 138 (63.0 %) | |

| AI 5 | as a companion in moments of solitude | 177 (80.8 %) | 42 (19.2 %) |

In analytical processing, nonparametric difference tests and logistic regression models are primarily used. The Wilcoxon rank sum test (W) was applied to assess differences, providing information on the presence of significant differences. To further evaluate these differences, an elementary descriptive analysis was conducted using arithmetic means and standard deviations across the indicator categories. The reliability was assessed using Cronbach's alpha, with an acceptable reliability threshold of 0.7. After confirming the reliability, the individual DL variables were averaged to create five factors, which were then included in the logistic regression models. All analytical procedures were conducted using the R programming environment, version 4.3.2 Eye Holes (R Core Team, 2023).

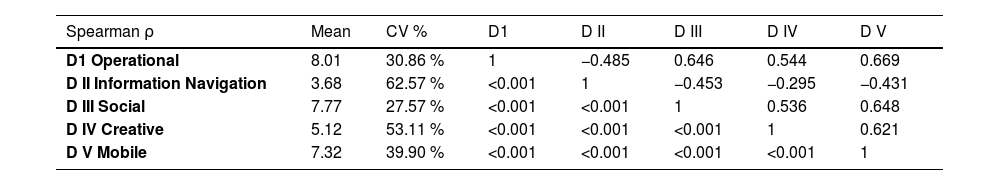

ResultsThe first subsection of the results focuses on evaluating DL factors. Relational analyses were conducted to assess the overall relationship between DL and ChatGPT. This was followed by a more detailed examination of the relationship between DL and ChatGPT use for specific purposes, as represented by the decomposed indicators (DI - DV). The reliability analysis supported the processing of aggregated indicators, yielding acceptable results (Cronbach's Alpha: DI = 0.96, DII = 0.899, DIII = 0.888, DIV = 0.921, and DV = 0.889). Table 4 presents the findings of the descriptive and relational analyses of the aggregated DL indicators. The main analytical procedures are conducted in chronological order and aligned with the individual research hypotheses. Logistic regression models well-suited to the characteristics of the dataset were primarily used in the analysis.

Descriptive and correlation analysis (Spearman ρ) - DL indicators (ISS).

| Spearman ρ | Mean | CV % | D1 | D II | D III | D IV | D V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 Operational | 8.01 | 30.86 % | 1 | −0.485 | 0.646 | 0.544 | 0.669 |

| D II Information Navigation | 3.68 | 62.57 % | <0.001 | 1 | −0.453 | −0.295 | −0.431 |

| D III Social | 7.77 | 27.57 % | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.536 | 0.648 |

| D IV Creative | 5.12 | 53.11 % | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.621 |

| D V Mobile | 7.32 | 39.90 % | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1 |

The results in Table 4 indicate that the highest level of DL was observed in the Operational indicator (D I), while the lowest was found in the creative indicator (DIV). The items under the Information Navigation indicator (DII) were negatively formulated, implying that a lower value corresponded to a higher DL level. In terms of variability, as measured by the coefficient of variation, the Social indicator (D III) showed the highest stability (CV = 27.57%), whereas the Information Navigation indicator (D II) showed the highest variability (CV = 62.57%). Relational analysis revealed that all the relationships between individual DL indicators were statistically significant at a level below 0.001. These relationships are relatively strong and could pose a risk of collinearity in the application of the multiple regression models. Simple binomial regression models are used to evaluate these relationships.

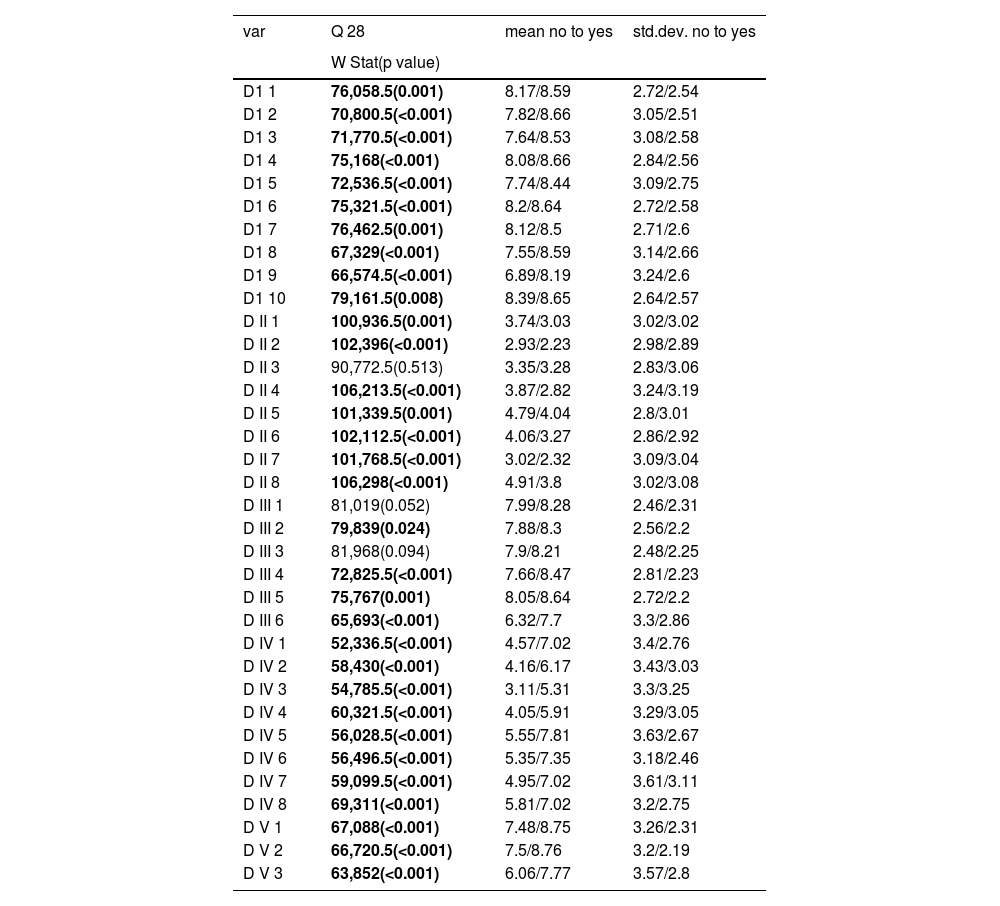

The results presented in Table 5 illustrate the relationships between the experience with the ChatGPT application and various DL indicators. The DL indicators (D) were measured on an ordinal scale ranging from 0 to 10 with 0 indicating complete disagreement and 10 indicating complete agreement with the corresponding statement. Experience with ChatGPT was assessed on a dichotomous scale, where the ‘NO’ category signifies that the respondent ‘did not try ChatGPT’,’ and the ‘YES’ category indicates that the respondent ‘tried ChatGPT’.’ These results help establish a connection between the levels of DL and the likelihood of having used ChatGPT, providing insights into how digital competencies influence the adoption and use of AI tools.

Have you tried how ChatGPT works? (Q 28) & DL (D) - test of differences and descriptive analysis.

| var | Q 28 | mean no to yes | std.dev. no to yes |

|---|---|---|---|

| W Stat(p value) | |||

| D1 1 | 76,058.5(0.001) | 8.17/8.59 | 2.72/2.54 |

| D1 2 | 70,800.5(<0.001) | 7.82/8.66 | 3.05/2.51 |

| D1 3 | 71,770.5(<0.001) | 7.64/8.53 | 3.08/2.58 |

| D1 4 | 75,168(<0.001) | 8.08/8.66 | 2.84/2.56 |

| D1 5 | 72,536.5(<0.001) | 7.74/8.44 | 3.09/2.75 |

| D1 6 | 75,321.5(<0.001) | 8.2/8.64 | 2.72/2.58 |

| D1 7 | 76,462.5(0.001) | 8.12/8.5 | 2.71/2.6 |

| D1 8 | 67,329(<0.001) | 7.55/8.59 | 3.14/2.66 |

| D1 9 | 66,574.5(<0.001) | 6.89/8.19 | 3.24/2.6 |

| D1 10 | 79,161.5(0.008) | 8.39/8.65 | 2.64/2.57 |

| D II 1 | 100,936.5(0.001) | 3.74/3.03 | 3.02/3.02 |

| D II 2 | 102,396(<0.001) | 2.93/2.23 | 2.98/2.89 |

| D II 3 | 90,772.5(0.513) | 3.35/3.28 | 2.83/3.06 |

| D II 4 | 106,213.5(<0.001) | 3.87/2.82 | 3.24/3.19 |

| D II 5 | 101,339.5(0.001) | 4.79/4.04 | 2.8/3.01 |

| D II 6 | 102,112.5(<0.001) | 4.06/3.27 | 2.86/2.92 |

| D II 7 | 101,768.5(<0.001) | 3.02/2.32 | 3.09/3.04 |

| D II 8 | 106,298(<0.001) | 4.91/3.8 | 3.02/3.08 |

| D III 1 | 81,019(0.052) | 7.99/8.28 | 2.46/2.31 |

| D III 2 | 79,839(0.024) | 7.88/8.3 | 2.56/2.2 |

| D III 3 | 81,968(0.094) | 7.9/8.21 | 2.48/2.25 |

| D III 4 | 72,825.5(<0.001) | 7.66/8.47 | 2.81/2.23 |

| D III 5 | 75,767(0.001) | 8.05/8.64 | 2.72/2.2 |

| D III 6 | 65,693(<0.001) | 6.32/7.7 | 3.3/2.86 |

| D IV 1 | 52,336.5(<0.001) | 4.57/7.02 | 3.4/2.76 |

| D IV 2 | 58,430(<0.001) | 4.16/6.17 | 3.43/3.03 |

| D IV 3 | 54,785.5(<0.001) | 3.11/5.31 | 3.3/3.25 |

| D IV 4 | 60,321.5(<0.001) | 4.05/5.91 | 3.29/3.05 |

| D IV 5 | 56,028.5(<0.001) | 5.55/7.81 | 3.63/2.67 |

| D IV 6 | 56,496.5(<0.001) | 5.35/7.35 | 3.18/2.46 |

| D IV 7 | 59,099.5(<0.001) | 4.95/7.02 | 3.61/3.11 |

| D IV 8 | 69,311(<0.001) | 5.81/7.02 | 3.2/2.75 |

| D V 1 | 67,088(<0.001) | 7.48/8.75 | 3.26/2.31 |

| D V 2 | 66,720.5(<0.001) | 7.5/8.76 | 3.2/2.19 |

| D V 3 | 63,852(<0.001) | 6.06/7.77 | 3.57/2.8 |

Note: NO - did not use ChatGPT, YES - used ChatGPT.

The non-parametric Wilcoxon (W) test was applied to assess the differences in DLbetween respondents who did and did not use ChatGPT. The first column of Table 4 displays the outcomes of this test, with the statistically significant results highlighted in bold. Most results were significant, indicating meaningful differences between the two groups. The subsequent columns present the results of the descriptive analysis, which should be considered when the significance of the differences is confirmed. In the domain of digital technology use (D1), the analysis revealed that individuals who tried ChatGPT exhibited significantly higher DL levels than those who did not. This suggests that engaging with ChatGPT is associated with a greater proficiency in using digital technologies. Conversely, significant differences were observed in negative experiences related to navigation and information retrieval via digital technologies (D2). The data suggest that individuals who have not attempted ChatGPT report a higher level of negative experiences in navigating and searching for information, potentially indicating lower DL or confidence in these areas.

Differences were also evident in the social domain (D3), in which respondents who tried ChatGPT demonstrated a higher level of responsibility than those who did not. In the realm of digital content creation (D4), the analysis of differences and descriptive statistics revealed that individuals who used ChatGPT had significantly greater knowledge of creating digital content than those who had not used the tool. Similar findings were observed for the final group of indicators related to the knowledge of mobile applications, with ChatGPT users exhibiting higher levels of expertise in this area. Overall, these results suggest that the respondents who interacted with ChatGPT exhibited a significantly higher level of DL across various domains, including social responsibility, digital content creation, and mobile application knowledge. This indicates that ChatGPT use is associated with enhanced digital skills and competencies.

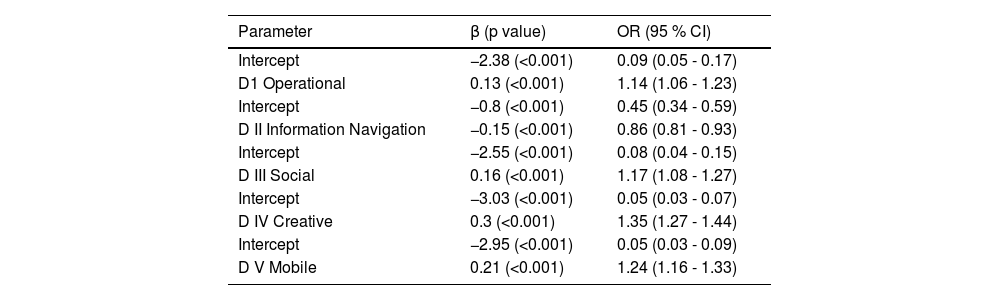

Table 6 presents the results of the binomial regression analysis assessing the relationship between the selected domains of DL and experience with the ChatGPT application. This analysis aims to identify whether specific aspects of DL significantly predict the likelihood of ChatGPT usage. The regression outcomes highlight the DL fields that are most strongly associated with the use of ChatGPTs.

Outcome of the Binomial Regression Models (H1) - Dependent Variable: ChatGPT Use, Independent Variable: ISS DL.

| Parameter | β (p value) | OR (95 % CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −2.38 (<0.001) | 0.09 (0.05 - 0.17) |

| D1 Operational | 0.13 (<0.001) | 1.14 (1.06 - 1.23) |

| Intercept | −0.8 (<0.001) | 0.45 (0.34 - 0.59) |

| D II Information Navigation | −0.15 (<0.001) | 0.86 (0.81 - 0.93) |

| Intercept | −2.55 (<0.001) | 0.08 (0.04 - 0.15) |

| D III Social | 0.16 (<0.001) | 1.17 (1.08 - 1.27) |

| Intercept | −3.03 (<0.001) | 0.05 (0.03 - 0.07) |

| D IV Creative | 0.3 (<0.001) | 1.35 (1.27 - 1.44) |

| Intercept | −2.95 (<0.001) | 0.05 (0.03 - 0.09) |

| D V Mobile | 0.21 (<0.001) | 1.24 (1.16 - 1.33) |

Note: OR: Odds ratio - Exp(β).

The results confirm a significant relationship between DL and the likelihood of using ChatGPT. Examining the sign of the β coefficients and the odds ratio, it becomes evident that a higher DL level corresponds to an increased probability of ChatGPT usage. The highest likelihood was observed in the creative domain, where respondents with a higher DL level were 35% more likely to use ChatGPT than those with a lower DL level. In the Mobile domain (D V), the model indicated that respondents with higher DL levels were 24% more likely to use ChatGPT than those with lower DL levels. Interestingly, D II Information Navigation demonstrated a positive effect, indicating that respondents with better navigation and information search skills were more inclined to use ChatGPT than those lacking these skills.

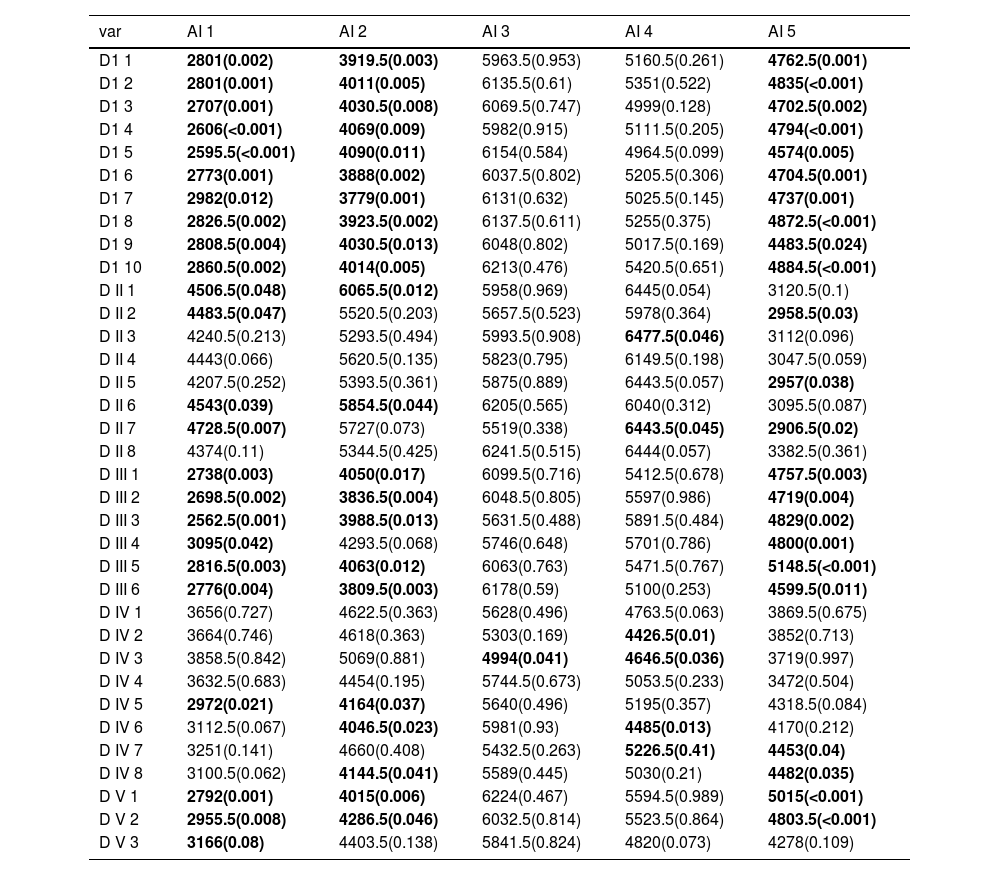

Table 7 presents an evaluation of the differences in the selected DL indicators (D) across various categories of ChatGPT usage for specific purposes. These categories include: (AI 1) Curiosity-driven usage (AI 2) Entertainment purposes, (AI 3) Work or school tasks (AI 4) Learning new information (AI 5) As companions during moments of solitude. This table compares these usage categories with the corresponding DL indicators (D).

For what purposes did you use the ChatGPT system (AI 5) & DL (D) - test of differences.

| var | AI 1 | AI 2 | AI 3 | AI 4 | AI 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 1 | 2801(0.002) | 3919.5(0.003) | 5963.5(0.953) | 5160.5(0.261) | 4762.5(0.001) |

| D1 2 | 2801(0.001) | 4011(0.005) | 6135.5(0.61) | 5351(0.522) | 4835(<0.001) |

| D1 3 | 2707(0.001) | 4030.5(0.008) | 6069.5(0.747) | 4999(0.128) | 4702.5(0.002) |

| D1 4 | 2606(<0.001) | 4069(0.009) | 5982(0.915) | 5111.5(0.205) | 4794(<0.001) |

| D1 5 | 2595.5(<0.001) | 4090(0.011) | 6154(0.584) | 4964.5(0.099) | 4574(0.005) |

| D1 6 | 2773(0.001) | 3888(0.002) | 6037.5(0.802) | 5205.5(0.306) | 4704.5(0.001) |

| D1 7 | 2982(0.012) | 3779(0.001) | 6131(0.632) | 5025.5(0.145) | 4737(0.001) |

| D1 8 | 2826.5(0.002) | 3923.5(0.002) | 6137.5(0.611) | 5255(0.375) | 4872.5(<0.001) |

| D1 9 | 2808.5(0.004) | 4030.5(0.013) | 6048(0.802) | 5017.5(0.169) | 4483.5(0.024) |

| D1 10 | 2860.5(0.002) | 4014(0.005) | 6213(0.476) | 5420.5(0.651) | 4884.5(<0.001) |

| D II 1 | 4506.5(0.048) | 6065.5(0.012) | 5958(0.969) | 6445(0.054) | 3120.5(0.1) |

| D II 2 | 4483.5(0.047) | 5520.5(0.203) | 5657.5(0.523) | 5978(0.364) | 2958.5(0.03) |

| D II 3 | 4240.5(0.213) | 5293.5(0.494) | 5993.5(0.908) | 6477.5(0.046) | 3112(0.096) |

| D II 4 | 4443(0.066) | 5620.5(0.135) | 5823(0.795) | 6149.5(0.198) | 3047.5(0.059) |

| D II 5 | 4207.5(0.252) | 5393.5(0.361) | 5875(0.889) | 6443.5(0.057) | 2957(0.038) |

| D II 6 | 4543(0.039) | 5854.5(0.044) | 6205(0.565) | 6040(0.312) | 3095.5(0.087) |

| D II 7 | 4728.5(0.007) | 5727(0.073) | 5519(0.338) | 6443.5(0.045) | 2906.5(0.02) |

| D II 8 | 4374(0.11) | 5344.5(0.425) | 6241.5(0.515) | 6444(0.057) | 3382.5(0.361) |

| D III 1 | 2738(0.003) | 4050(0.017) | 6099.5(0.716) | 5412.5(0.678) | 4757.5(0.003) |

| D III 2 | 2698.5(0.002) | 3836.5(0.004) | 6048.5(0.805) | 5597(0.986) | 4719(0.004) |

| D III 3 | 2562.5(0.001) | 3988.5(0.013) | 5631.5(0.488) | 5891.5(0.484) | 4829(0.002) |

| D III 4 | 3095(0.042) | 4293.5(0.068) | 5746(0.648) | 5701(0.786) | 4800(0.001) |

| D III 5 | 2816.5(0.003) | 4063(0.012) | 6063(0.763) | 5471.5(0.767) | 5148.5(<0.001) |

| D III 6 | 2776(0.004) | 3809.5(0.003) | 6178(0.59) | 5100(0.253) | 4599.5(0.011) |

| D IV 1 | 3656(0.727) | 4622.5(0.363) | 5628(0.496) | 4763.5(0.063) | 3869.5(0.675) |

| D IV 2 | 3664(0.746) | 4618(0.363) | 5303(0.169) | 4426.5(0.01) | 3852(0.713) |

| D IV 3 | 3858.5(0.842) | 5069(0.881) | 4994(0.041) | 4646.5(0.036) | 3719(0.997) |

| D IV 4 | 3632.5(0.683) | 4454(0.195) | 5744.5(0.673) | 5053.5(0.233) | 3472(0.504) |

| D IV 5 | 2972(0.021) | 4164(0.037) | 5640(0.496) | 5195(0.357) | 4318.5(0.084) |

| D IV 6 | 3112.5(0.067) | 4046.5(0.023) | 5981(0.93) | 4485(0.013) | 4170(0.212) |

| D IV 7 | 3251(0.141) | 4660(0.408) | 5432.5(0.263) | 5226.5(0.41) | 4453(0.04) |

| D IV 8 | 3100.5(0.062) | 4144.5(0.041) | 5589(0.445) | 5030(0.21) | 4482(0.035) |

| D V 1 | 2792(0.001) | 4015(0.006) | 6224(0.467) | 5594.5(0.989) | 5015(<0.001) |

| D V 2 | 2955.5(0.008) | 4286.5(0.046) | 6032.5(0.814) | 5523.5(0.864) | 4803.5(<0.001) |

| D V 3 | 3166(0.08) | 4403.5(0.138) | 5841.5(0.824) | 4820(0.073) | 4278(0.109) |

The DL indicators were recorded on an ordinal scale from 0 to 10, where 0 represented absolute disagreement and 10 represented absolute agreement with a particular statement. The AI indicators were evaluated on a dichotomous scale, with 0 indicating ‘No, I did not use it this way’ and 1 indicating ‘Yes, I used it this way’.’ The nonparametric Wilcoxon (W) test was used to evaluate the differences in DL between the categories of experience with ChatGPT. Significant differences are highlighted in bold font. Notably, the most significant differences were observed for AI 1, AI 2, and AI 5. In contrast, the AI 3 and AI 4 indicators showed only a few statistically significant differences. When focusing on DL, the most notable differences in ChatGPT usage for the selected purposes were found in D1 (general use of digital technologies) and DIII (social aspects of digital technology use). Table 7 summarises these findings.

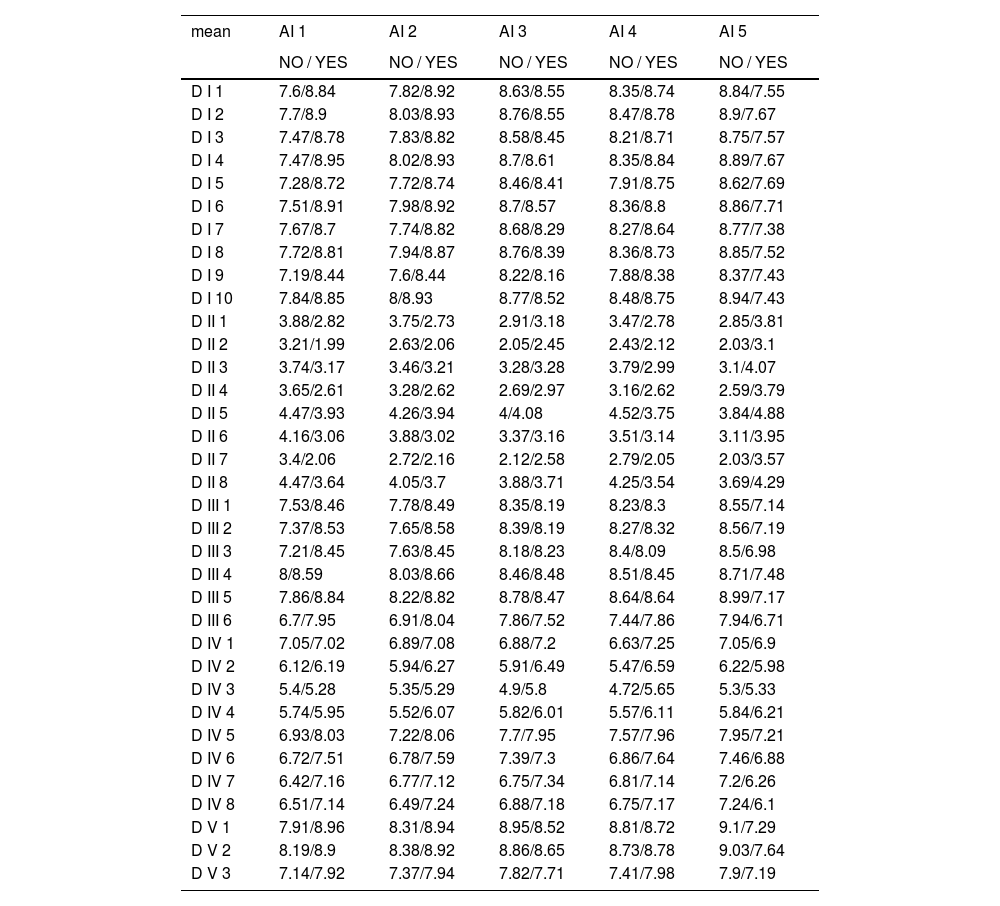

Table 8 presents the average values of the selected DL fields (D) within the AI 5 categories (NO - No, I did not use it this way; YES - Yes, I used it this way). The interpretations focused only on indicators that were considered significantly different (Table 4). In the field of digital technology use (D 1), significant differences were observed in categories AI 1, AI 2, and AI 5 categories. For AI 1 and AI 2, higher average DL values were noted in Category 1, indicating that respondents who used ChatGPT to test its capabilities and for fun (entertainment) had a higher DL rate. Conversely, in AI 5, where the respondents used ChatGPT as a companion during moments of solitude, a lower DL rate was evident. Similar differences were found in the social field (D III), where respondents who used ChatGPT to test its possibilities (AI 1) and for fun (entertainment) (AI 2) exhibited higher DL rates. By contrast, those who used ChatGPT as a companion during moments of solitude (AI = 5) demonstrated a lower DL rate. These results confirmed that ChatGPT usage varied across different DL levels.

For what purposes did you use the ChatGPT system (AI 5) & DL (D) - arithmetic mean in second-order sorting.

| mean | AI 1 | AI 2 | AI 3 | AI 4 | AI 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO / YES | NO / YES | NO / YES | NO / YES | NO / YES | |

| D I 1 | 7.6/8.84 | 7.82/8.92 | 8.63/8.55 | 8.35/8.74 | 8.84/7.55 |

| D I 2 | 7.7/8.9 | 8.03/8.93 | 8.76/8.55 | 8.47/8.78 | 8.9/7.67 |

| D I 3 | 7.47/8.78 | 7.83/8.82 | 8.58/8.45 | 8.21/8.71 | 8.75/7.57 |

| D I 4 | 7.47/8.95 | 8.02/8.93 | 8.7/8.61 | 8.35/8.84 | 8.89/7.67 |

| D I 5 | 7.28/8.72 | 7.72/8.74 | 8.46/8.41 | 7.91/8.75 | 8.62/7.69 |

| D I 6 | 7.51/8.91 | 7.98/8.92 | 8.7/8.57 | 8.36/8.8 | 8.86/7.71 |

| D I 7 | 7.67/8.7 | 7.74/8.82 | 8.68/8.29 | 8.27/8.64 | 8.77/7.38 |

| D I 8 | 7.72/8.81 | 7.94/8.87 | 8.76/8.39 | 8.36/8.73 | 8.85/7.52 |

| D I 9 | 7.19/8.44 | 7.6/8.44 | 8.22/8.16 | 7.88/8.38 | 8.37/7.43 |

| D I 10 | 7.84/8.85 | 8/8.93 | 8.77/8.52 | 8.48/8.75 | 8.94/7.43 |

| D II 1 | 3.88/2.82 | 3.75/2.73 | 2.91/3.18 | 3.47/2.78 | 2.85/3.81 |

| D II 2 | 3.21/1.99 | 2.63/2.06 | 2.05/2.45 | 2.43/2.12 | 2.03/3.1 |

| D II 3 | 3.74/3.17 | 3.46/3.21 | 3.28/3.28 | 3.79/2.99 | 3.1/4.07 |

| D II 4 | 3.65/2.61 | 3.28/2.62 | 2.69/2.97 | 3.16/2.62 | 2.59/3.79 |

| D II 5 | 4.47/3.93 | 4.26/3.94 | 4/4.08 | 4.52/3.75 | 3.84/4.88 |

| D II 6 | 4.16/3.06 | 3.88/3.02 | 3.37/3.16 | 3.51/3.14 | 3.11/3.95 |

| D II 7 | 3.4/2.06 | 2.72/2.16 | 2.12/2.58 | 2.79/2.05 | 2.03/3.57 |

| D II 8 | 4.47/3.64 | 4.05/3.7 | 3.88/3.71 | 4.25/3.54 | 3.69/4.29 |

| D III 1 | 7.53/8.46 | 7.78/8.49 | 8.35/8.19 | 8.23/8.3 | 8.55/7.14 |

| D III 2 | 7.37/8.53 | 7.65/8.58 | 8.39/8.19 | 8.27/8.32 | 8.56/7.19 |

| D III 3 | 7.21/8.45 | 7.63/8.45 | 8.18/8.23 | 8.4/8.09 | 8.5/6.98 |

| D III 4 | 8/8.59 | 8.03/8.66 | 8.46/8.48 | 8.51/8.45 | 8.71/7.48 |

| D III 5 | 7.86/8.84 | 8.22/8.82 | 8.78/8.47 | 8.64/8.64 | 8.99/7.17 |

| D III 6 | 6.7/7.95 | 6.91/8.04 | 7.86/7.52 | 7.44/7.86 | 7.94/6.71 |

| D IV 1 | 7.05/7.02 | 6.89/7.08 | 6.88/7.2 | 6.63/7.25 | 7.05/6.9 |

| D IV 2 | 6.12/6.19 | 5.94/6.27 | 5.91/6.49 | 5.47/6.59 | 6.22/5.98 |

| D IV 3 | 5.4/5.28 | 5.35/5.29 | 4.9/5.8 | 4.72/5.65 | 5.3/5.33 |

| D IV 4 | 5.74/5.95 | 5.52/6.07 | 5.82/6.01 | 5.57/6.11 | 5.84/6.21 |

| D IV 5 | 6.93/8.03 | 7.22/8.06 | 7.7/7.95 | 7.57/7.96 | 7.95/7.21 |

| D IV 6 | 6.72/7.51 | 6.78/7.59 | 7.39/7.3 | 6.86/7.64 | 7.46/6.88 |

| D IV 7 | 6.42/7.16 | 6.77/7.12 | 6.75/7.34 | 6.81/7.14 | 7.2/6.26 |

| D IV 8 | 6.51/7.14 | 6.49/7.24 | 6.88/7.18 | 6.75/7.17 | 7.24/6.1 |

| D V 1 | 7.91/8.96 | 8.31/8.94 | 8.95/8.52 | 8.81/8.72 | 9.1/7.29 |

| D V 2 | 8.19/8.9 | 8.38/8.92 | 8.86/8.65 | 8.73/8.78 | 9.03/7.64 |

| D V 3 | 7.14/7.92 | 7.37/7.94 | 7.82/7.71 | 7.41/7.98 | 7.9/7.19 |

Note: NO - did not use ChatGPT for the particular purpose, YES - used ChatGPT for the particular purpose.

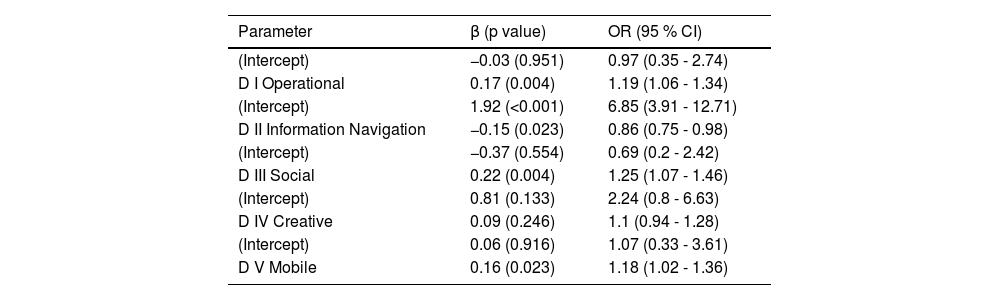

Table 9 presents the evaluation of the significance of the relationship between ChatGPT usage for testing purposes and DL. The outcomes of the binomial regression models indicate that all relationships except for the D IV Creative field are statistically significant. Based on the β coefficient and the odds ratio, respondents with a higher DL rate are more likely to use ChatGPT for testing purposes than those with a lower DL rate. The strongest tendency to use ChatGPT for testing was observed in the social domain (D III). Respondents with higher DL in this area were 25% more likely to test ChatGPT than those with lower literacy in this field. It is important to note the negative formulation of the D II Information Navigation items, where a lower value signifies a higher DL rate. This suggests that a greater intention to try ChatGPT is associated with better skills in navigating and searching for information. Table 10 presents the outcomes of the evaluation of the relationships between ChatGPT use for entertainment purposes and the DL rate.

Outcome of Binomial Regression Models (H2) - Dependent Variable: Purpose of ChatGPT Use (Just to Try It Out or Curiosity About What It Can Do); Independent Variable: ISS DL.

| Parameter | β (p value) | OR (95 % CI) |

|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −0.03 (0.951) | 0.97 (0.35 - 2.74) |

| D I Operational | 0.17 (0.004) | 1.19 (1.06 - 1.34) |

| (Intercept) | 1.92 (<0.001) | 6.85 (3.91 - 12.71) |

| D II Information Navigation | −0.15 (0.023) | 0.86 (0.75 - 0.98) |

| (Intercept) | −0.37 (0.554) | 0.69 (0.2 - 2.42) |

| D III Social | 0.22 (0.004) | 1.25 (1.07 - 1.46) |

| (Intercept) | 0.81 (0.133) | 2.24 (0.8 - 6.63) |

| D IV Creative | 0.09 (0.246) | 1.1 (0.94 - 1.28) |

| (Intercept) | 0.06 (0.916) | 1.07 (0.33 - 3.61) |

| D V Mobile | 0.16 (0.023) | 1.18 (1.02 - 1.36) |

Note: OR: Odds ratio - Exp(β).

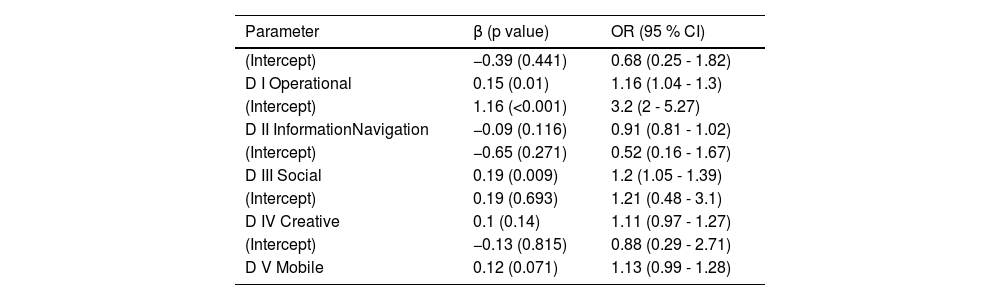

Outcome of Binomial Regression Models (H3) - Dependent Variable: Purpose of ChatGPT Use (For Fun, Entertainment), Independent Variable: ISS DL.

| Parameter | β (p value) | OR (95 % CI) |

|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −0.39 (0.441) | 0.68 (0.25 - 1.82) |

| D I Operational | 0.15 (0.01) | 1.16 (1.04 - 1.3) |

| (Intercept) | 1.16 (<0.001) | 3.2 (2 - 5.27) |

| D II InformationNavigation | −0.09 (0.116) | 0.91 (0.81 - 1.02) |

| (Intercept) | −0.65 (0.271) | 0.52 (0.16 - 1.67) |

| D III Social | 0.19 (0.009) | 1.2 (1.05 - 1.39) |

| (Intercept) | 0.19 (0.693) | 1.21 (0.48 - 3.1) |

| D IV Creative | 0.1 (0.14) | 1.11 (0.97 - 1.27) |

| (Intercept) | −0.13 (0.815) | 0.88 (0.29 - 2.71) |

| D V Mobile | 0.12 (0.071) | 1.13 (0.99 - 1.28) |

Note: OR: Odds ratio - Exp(β).

The outcomes in Table 10 indicate that most relationships across the various DL fields are statistically significant, with the exception of the D IV Creative field. These significant relationships suggest that a higher DL rate is correlated with a greater likelihood of using ChatGPT for entertainment. The strongest correlation was observed in the D III Social field, where respondents with higher DL were 25% more likely to use ChatGPT for entertainment than those with lower DL. Another area of investigation was the use of ChatGPT in the work and educational contexts, as shown in Table 11.

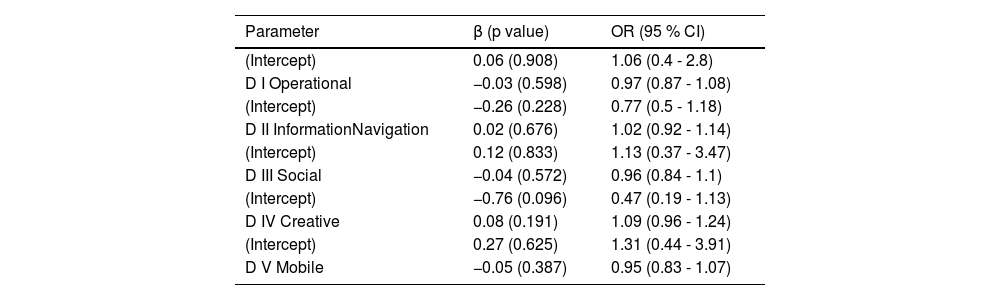

Outcome of the Binomial Regression Models (H4) - Dependent Variable: Purpose of ChatGPT Use: For Tasks at Work/School, Independent Variable: ISS DL.

| Parameter | β (p value) | OR (95 % CI) |

|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.06 (0.908) | 1.06 (0.4 - 2.8) |

| D I Operational | −0.03 (0.598) | 0.97 (0.87 - 1.08) |

| (Intercept) | −0.26 (0.228) | 0.77 (0.5 - 1.18) |

| D II InformationNavigation | 0.02 (0.676) | 1.02 (0.92 - 1.14) |

| (Intercept) | 0.12 (0.833) | 1.13 (0.37 - 3.47) |

| D III Social | −0.04 (0.572) | 0.96 (0.84 - 1.1) |

| (Intercept) | −0.76 (0.096) | 0.47 (0.19 - 1.13) |

| D IV Creative | 0.08 (0.191) | 1.09 (0.96 - 1.24) |

| (Intercept) | 0.27 (0.625) | 1.31 (0.44 - 3.91) |

| D V Mobile | −0.05 (0.387) | 0.95 (0.83 - 1.07) |

Note: OR: Odds ratio - Exp(β).

Table 11 indicates that there is no statistically significant relationship between the intention to use or not use ChatGPT for school or work tasks and DL. This suggests that the DL level does not influence whether respondents are more or less likely to use ChatGPT to complete school or work-related tasks. Therefore, it cannot be confirmed whether individuals with higher DL levels are either more or less inclined to use ChatGPT for specific purposes.

Table 12 presents the relationship between DL and the use of ChatGPT to obtain new information.

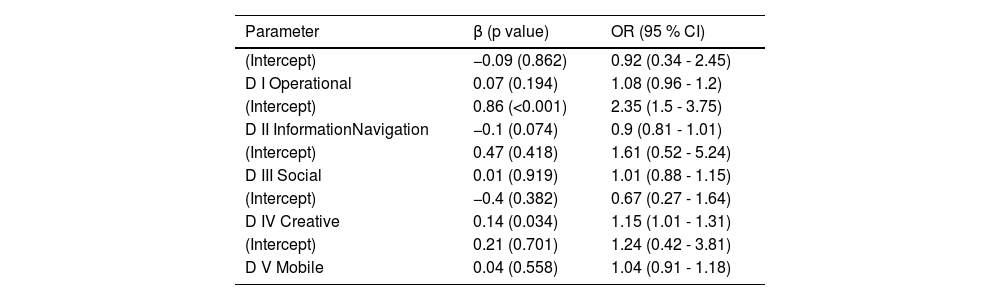

Outcome of the Binomial Regression Models (H5) - Dependent Variable: Purpose of Using ChatGPT (To Learn Something New), Independent Variable: ISS DL.

| Parameter | β (p value) | OR (95 % CI) |

|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −0.09 (0.862) | 0.92 (0.34 - 2.45) |

| D I Operational | 0.07 (0.194) | 1.08 (0.96 - 1.2) |

| (Intercept) | 0.86 (<0.001) | 2.35 (1.5 - 3.75) |

| D II InformationNavigation | −0.1 (0.074) | 0.9 (0.81 - 1.01) |

| (Intercept) | 0.47 (0.418) | 1.61 (0.52 - 5.24) |

| D III Social | 0.01 (0.919) | 1.01 (0.88 - 1.15) |

| (Intercept) | −0.4 (0.382) | 0.67 (0.27 - 1.64) |

| D IV Creative | 0.14 (0.034) | 1.15 (1.01 - 1.31) |

| (Intercept) | 0.21 (0.701) | 1.24 (0.42 - 3.81) |

| D V Mobile | 0.04 (0.558) | 1.04 (0.91 - 1.18) |

Note: OR: Odds ratio - Exp(β).

The analysis in Table 12 reveals that the only significant field related to the use of ChatGPT to obtain new information is the D IV Creative field. The positive regression coefficient and odds ratio greater than 1 indicate that individuals with higher DL in the creative field are 1.15 times more likely to use ChatGPT to acquire new information than those with lower literacy in this domain. This finding suggests that creativity-related digital skills enhance the likelihood of leveraging ChatGPT as an information-gathering tool.

As presented in Table 13, the final section of the analysis aimed to evaluate the relationship between DL and the use or non-use of ChatGPT as a companion during moments of solitude.

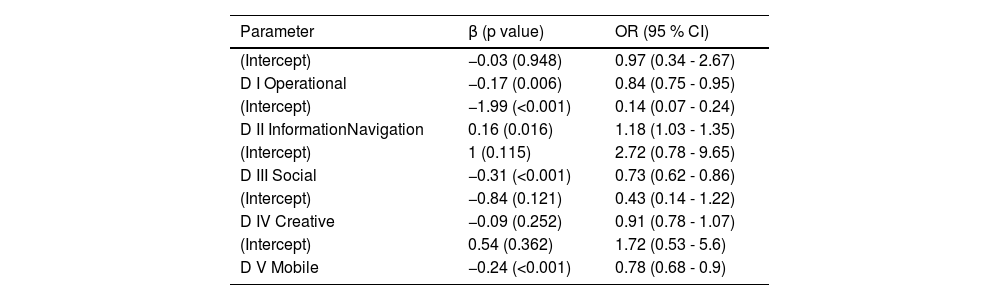

Outcome of the Binomial Regression Models (H6) - Dependent Variable: Purpose of ChatGPT Use (As a Companion in Moments of Solitude), Independent Variable: ISS DL.

| Parameter | β (p value) | OR (95 % CI) |

|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −0.03 (0.948) | 0.97 (0.34 - 2.67) |

| D I Operational | −0.17 (0.006) | 0.84 (0.75 - 0.95) |

| (Intercept) | −1.99 (<0.001) | 0.14 (0.07 - 0.24) |

| D II InformationNavigation | 0.16 (0.016) | 1.18 (1.03 - 1.35) |

| (Intercept) | 1 (0.115) | 2.72 (0.78 - 9.65) |

| D III Social | −0.31 (<0.001) | 0.73 (0.62 - 0.86) |

| (Intercept) | −0.84 (0.121) | 0.43 (0.14 - 1.22) |

| D IV Creative | −0.09 (0.252) | 0.91 (0.78 - 1.07) |

| (Intercept) | 0.54 (0.362) | 1.72 (0.53 - 5.6) |

| D V Mobile | −0.24 (<0.001) | 0.78 (0.68 - 0.9) |

Note: OR: Odds ratio - Exp(β).

If we examine the statistical significance of the relationships presented in Table 13, it becomes evident that the only relationship deemed significant is D IV Creative. The regression coefficients were negative for all statistically significant indicators and the odds ratios were below 1. This suggests that respondents with lower levels of DL in the D I Operational, D III Social, D IV Creative, and D V Mobile fields were more likely to use ChatGPT as a companion during moments of solitude. Similar findings were observed for D II Information Navigation, where the negative formulation of survey items indicated that a higher level of navigation literacy was associated with a decreased likelihood of using ChatGPT as a companion.

DiscussionThis study primarily focuses on two key areas: Internet-related DL and ChatGPT usage. DL was assessed using the ISS, and ChatGPT use was measured with dichotomous scale items. The initial findings revealed that the highest DL levels were observed in D I Operational, with the lowest scores in D IV Creative. Regarding ChatGPT usage, 21.37% of the respondents reported experience with the application. The most common reason for using ChatGPT was to ‘Just to try it out’ (80.4%), while the least common was using it ‘As a companion in moments of solitude’ (19.2%). These results indicate that the social benefits of ChatGPT remain underexplored. This notion is supported by a recent study by Alzyoudi and Mazroui (2024) that highlights the complexity of the social support provided by ChatGPT. They identified key capabilities, such as context awareness, emotion recognition, generative abilities, adaptability, multimodal understanding, and continuous learning, as factors that enhance social support. Other studies have also recognised these aspects (Abdullah, Madain & Jararweh, 2022; Smith et al., 2023). Positive social influence can increase the perceived usefulness and ease of ChatGPT, boosting user confidence and reducing barriers to adoption (Menon & Shilpa, 2023). From the perspective of the relationship between DL and ChatGPT, the research was divided into six research hypotheses. Their evaluations yielded interesting results.

For H1 (‘There is a significant relationship between the intention to use ChatGPT and DL, as measured by the Internet Skills Scale (ISS)’), the study focused on general ChatGPT use and found that respondents with higher DL levels were more likely to use ChatGPT. Digital skills tend to remain relatively stable over time, as noted by Kappeler (2024), who linked DL to optimistic attitudes toward cybernetics in 2023. The importance of digital skills continues to grow, with researchers such as Gillespie (2024) and Van Laar, Van Deursen, Van Dijk and De Haan (2020a, b) suggesting a recursive relationship between digital skills, cybernetic optimism, Internet use, and a sense of inclusion in the information society. Higher socioeconomic backgrounds often facilitate the development of advanced digital skills, leading to more sophisticated use and further skill enhancement. However, experts emphasise the need to consider digital skills in the context of social and digital inequalities (Chen and Li, 2022). The expansion of the Internet alone will not eliminate these inequalities; in fact, it may exacerbate them (Schradie, 2020). As Gruber and Hargittai (2023) argue, as digital tools become more integral to daily life, the ability to use them effectively becomes essential. Those lacking the necessary digital skills increasingly face disadvantages in various aspects of life, including leisure, health, and finance, where they may pay higher prices or miss opportunities.

For H2 (‘The intention to use ChatGPT to test its capabilities is significantly related to DL, as measured by the ISS’) and H3 (‘The intention to use ChatGPT for entertainment purposes is significantly related to DL, as measured by the ISS’), the outcomes were similar. In addition to content creation, the results indicate that respondents with higher DL levels are more likely to use ChatGPT to test both its capabilities and entertainment. Specifically, ChatGPT use for these purposes is more prevalent among those with advanced skills in general Internet use, Internet navigation, social aspects, and mobile device use. This aligns with the findings of Nikghalb and Cheng (2024), who noted that over half of the user interactions with ChatGPT revolve around playful engagements, which are multifaceted and contribute positively to the development of AI tools. The use of ChatGPT to explore its capabilities and entertainment requires a certain DL level, as confirmed by our research findings. Hargittai, Gruber, Djukaric, Fuchs and Brombach (2020) suggested that as digital skills continue to improve, Internet users face new challenges, further uncovering the capabilities of ChatGPT and raising expectations for AI tools.

Hypothesis 4 focused on investigating the relationship between the intention to use ChatGPT for educational or work purposes and DL, as measured by ISS (H4: ‘The intention to use ChatGPT for educational or work purposes is significantly related to DL, as measured by ISS’). In this field, no significant relationship with the DL was found. Although the use of ChatGPT for educational and work purposes is frequently mentioned in the literature, the DL construct has not been investigated separately (Rice, Crouse, Winter & Rice, 2024; Sharma & Yadav, 2022). However, DL significantly impacts ChatGPT adoption, long-term use, and the enhancement of digital skills (Bejaković & Mrnjavac, 2020; Erwin & Mohammed, 2022). These processes can be explained conceptually using the UTAUT model. Masoomi et al. (2024) used a modified UTAUT model to explore the significant predictors of student ChatGPT adoption, incorporating constructs such as digital skills, human-ChatGPT interaction, performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influences, and behavioural intention. Both the traditional and modified versions of the UTAUT model emphasise the synergy of various constructs for ChatGPT adoption, not just DL and digital skills (Kim, 2023; Menon & Shilpa, 2023).

By contrast, Ali, Murray, Momin and Al-Anzi (2023) took a more sceptical view, noting that while ChatGPT may exponentially increase user knowledge, the quality of the information generated does not necessarily lead to a deep understanding of complex systems. For work-related purposes, ChatGPT use is extensive and influenced by job structure and content, requiring a corresponding DL level that is often acquired through training (Javaid, Haleem, & Singh, 2022; Zarifhonarvar, 2024). From a consumer perspective, ChatGPT offers benefits such as enhanced engagement, personalised experiences, and cost efficiency; however, these are balanced against concerns over consumer welfare, bias, disinformation, privacy, and ethics (Alghizzawi, 2024; Arman & Lamiyar, 2023).

For H5 (‘The intention to use ChatGPT to gain new knowledge is significantly related to DL, as measured by the ISS’), the analysis found that the relationship between ChatGPT use for acquiring new knowledge was significant only in the domain of content creation. This suggests that respondents with higher DL levels in content creation were more likely to use ChatGPT for educational purposes. The importance of DL in ChatGPT for content creation was supported by Huang, Coleman, Gachago and Van Belle (2023); Whalen and Mouza (2023), and Lund, Agbaji and Teel (2023). Madunić et al. (2024) also highlight that strategic and well-planned use of ChatGPT in content creation can lead to substantial time and cost efficiencies.

The findings from H6 (‘The intention to use ChatGPT as a companion during solitary time is significantly related to DL, as measured by the ISS’) stand out as particularly intriguing. Content creation is the only DL field that does not exhibit a significant relationship in this context. For other DL domains such as general Internet use, Internet navigation, social aspects, and mobile device use, the results suggest that respondents with lower DL levels are more likely to use ChatGPT for companionship during moments of solitude. This trend is particularly relevant for older adults who tend to have lower DL levels and may seek social support through digital means. This is consistent with the findings of Oh et al. (2021), Schreurs, Quan-Haase and Martin (2017), and Zapletal, Wells, Russell and Skinner (2023) who noted the importance of social support tools for older adults experiencing social isolation. Alzyoudi and Mazroui (2024) further confirmed this trend among respondents aged over 50 who used ChatGPT for social support during periods of solitude, regardless of age, gender, education, or employment status.

The study's outcomes revealed variability within DL dimensions and their influence on ChatGPT usage across different contexts, including testing purposes, entertainment, and moments of solitude (Al Lily, Ismail, Abunaser, Al-Lami & Abdullatif, 2023). These patterns align with specific age categories, each displaying varying DL levels (Wolf & Maier, 2024). Technological advancements are likely to drive an increase in DL, driven by user experience, frequent Internet use, AI tools, and socialisation effects (Morgan, Sibson & Jackson, 2022). This suggests that future AI tool usage, even in isolation, may not necessarily correlate with low DL levels, especially as DL among older populations is expected to increase (Martínez-Alcalá et al., 2021; Yoo, 2021). Ethical considerations and perceived risks also played a role in this evolution (Kong et al., 2023; Ray, 2023). Future research should explore how different ChatGPT usage intentions affect DL requirements across specific fields, considering the UX and technologies within distinct demographic groups (Hosseini, Gao, Liebovitz & Carvalho, 2023). In addition, it is crucial to examine which dominant DL elements influence ChatGPT adoption and comprehensive AI tool use.

These findings are crucial for advancing DL systems that reflect the varying sensitivities in DL related to the different Internet skills needed to control and use AI tools (Kozyreva, Lewandowsky & Hertwig, 2020; Van Laar, Van Deursen, Van Dijk & De Haan, 2017). The rapid adoption of AI tools is linked to the pace of acquiring Internet skills, which, in turn, enhances DL.

This study offers numerous practical benefits for educators and policymakers interested in integrating AI technologies into educational systems and promoting DL. ChatGPT enables institutions to create more personalised, motivating, and effective learning solutions. The advantages of personalised education are already being monitored, forming part of evolving educational systems (Rakap, 2024). According to the World Economic Forum (2018), AI chatbots offer more than just new methods of acquiring knowledge and 24-hour accessibility; they also reduce teacher workloads and facilitate personalised teaching and mentoring (Hyatt, 2018). Some studies have highlighted the transformative impact of ChatGPT on educational environments, potentially reshaping traditional systems (Pham et al., 2023). This highlights the need to educate both teachers and students about ChatGPT's capabilities and limitations (Baidoo-Anu & Ansah, 2023; Gill, Xu & Patros, 2024).

Collaboration among policymakers, educators, researchers, and technological experts is essential for safely and constructively integrating generative AI tools, enhancing educational systems, and boosting DL. Tran and Tran (2023) emphasised the importance of fostering critical DL, which equips students to effectively navigate and engage in the online world. Critical DL includes the ability to analyse and critically evaluate digital information, understand the sociocultural impact of digital technologies, and engage responsibly online (Knight, Dooly & Barberà, 2023; Pangrazio & Selwyn, 2019). Incorporating critical DL into education can strengthen students' ability to assess the credibility, reliability, and bias of digital content and news sources.

This skill set enables students to address complex digital environments, engage ethically and responsibly, and make informed decisions (Pangrazio & Selwyn, 2019). Developing these abilities can also enhance media literacy, as demonstrated in several studies (Leaning, 2019; Manca, Bocconi & Gleason, 2021). Additionally, it would protect students from disinformation, a topic that has thus far been underrepresented in education. Further research is required to fully understand ChatGPT's impact on critical DL and the development of ethical educational practices in the digital age (Bacalja, Aguilera & Castrillón-Ángel, 2021; Talib, 2018; Watt, 2019).

Our study did not delve into ChatGPT use within specific population groups, such as individuals with disabilities, which presents an area for future research. Although ChatGPT was not explicitly designed for healthcare, it provides answers to a wide range of questions, including health-related enquiries (Goodman, Patrinely & Stone, 2023). This makes it a readily accessible resource for seeking health information and advice, which is particularly important for individuals with chronic illnesses (Madrigal & Escoffery, 2019). Studies have shown that AI tools assist people with multiple sclerosis (Maida, Moccia & Palladino, 2024), provide mental health psychoeducation (Maurya, Montesinos, Bogomaz & DeDiego, 2023), and support individuals with dementia and other cognitive challenges (Hristidis, Ruggiano, Brown, Ganta & Stewart, 2023). ChatGPT also shows promise in addressing social isolation, a concern that has intensified post-pandemic (Alzyoudi & Mazroui, 2024).

Future research should focus on the DL of diverse population groups and the factors influencing AI tool adoption, particularly ChatGPT. Developing tools to evaluate various digital skills related to daily internet use, socio-economic influences, and cybernetic optimism is essential (Kappeler, 2024). DL must evolve dynamically to impact the adoption and use of AI tools effectively. By expanding DL's scope and impact, we can reduce digital inequality and leverage technological development to enhance all aspects of work and personal life, ultimately boosting national digital competitiveness.

Strengths and limitations of the studyThe primary strength of this study lies in its pioneering investigation of the relationship between DL and the use of generative AI tools like ChatGPT, which is anticipated to become a critical digital skill in the future. Additional strengths include the research sample's size and structure. However, the study also has some limitations. The first is the timing of the research and data collection. Given the rapid advancements in AI technologies like ChatGPT, the findings may become outdated quickly. Our research captures the early stages of ChatGPT adoption in the Czech Republic. As its popularity grows rapidly, long-term trends are difficult to forecast. Conducted one year after ChatGPT's launch, the study reflects the observation that media technologies often take decades to fully integrate into society, allowing for the assessment of their broader socio-economic and political impacts (Biagi, 2011). Thus, this study's value lies in its documentation of initial trends during the early adoption phase of generative AI.

A second limitation relates to the socio-cultural context of the respondents. The Czech Republic has relatively high levels of digital literacy, which may have influenced the findings (Moravec, Hynek, Gavurova & Kubak, 2024). In countries with different socio-cultural settings or lower digital literacy levels, results might vary, likely depending on technological adaptation (Pangrazio, Godhe & Ledesma, 2020; Sun, Liu & Lu, 2023; Thatcher, 2009). These considerations demonstrate the significant role generative AI plays in shaping the development of digital literacy. The study's results stress the need for ongoing research into DL development and adaptation to emerging skills, such as prompt engineering - crafting precise, structured inputs to enhance AI responses. Recent studies indicate that greater proficiency in prompt engineering correlates with the quality of outputs from large language models (Knoth, Tolzin, Janson & Leimeister, 2024; Lee, Jung & Jeon, 2024).

A key challenge for future research will be to track these trends through longitudinal studies to better understand how they evolve over time.

ConclusionThe main objective of this study was to explore and quantify the relationships between DL and selected fields of AI use, specifically ChatGPT, to identify patterns of ChatGPT usage and uncover the development potential of DL concepts. Conducted on a sample of the Czech population, the study employed non-parametric difference tests, relational analyses, and binomial logistic regression models to evaluate the connections between DL and ChatGPT usage. The findings confirmed that a higher DL rate is associated with a greater likelihood of using ChatGPT, particularly for testing its capabilities and for entertainment, while a lower DL rate correlates with using ChatGPT as a companion in moments of solitude.

These results will support the development of DL systems in relation to emerging AI tools, considering adoption rates as well as socio-economic and technical potentials, beyond just socio-demographic characteristics. It is anticipated that socio-demographic factors will play a diminishing role in AI tool adoption as DL claims and rates evolve across different population groups.

The study's findings are valuable for AI regulators, digitalization experts, policymakers, and AI developers. They also highlight the urgent need to address the impact of DL on digital inequality, which may worsen with the continued advancement of AI tools. As numerous studies suggest, the full potential of advanced technologies can only be realized if they are accessible to all individuals, regardless of socioeconomic background, gender, bias, or geographic location. Therefore, addressing digital inequality, DL, and inclusive practices has become increasingly critical.

Data availabilityData will be made available on request.

Ethical approvalAll procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

CRediT authorship contribution statementVaclav Moravec: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Investigation, Conceptualization. Nik Hynek: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Resources, Methodology, Data curation. Beata Gavurova: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation. Martin Rigelsky: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Software, Formal analysis.

This article was produced with the support of the Technology Agency of the Czech Republic under the SIGMA Programme, project TQ01000100 Newsroom AI: public service in the era of automated journalism and by the Institutional support by Charles University, Program Cooperatio (IPS FSV). This research was funded by the Ministry of Education, Research, Development and Youth of the Slovak Republic and the Slovak Academy of Sciences, VEGA No. 1/0554/24.