Digital transformation is pivotal in corporate development, fundamentally reshaping core business components. Although it is recognized that enhanced digital capabilities improve performance through data-driven processes, existing research has primarily focused on large enterprises. As a result, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) often hesitate to invest due to uncertainties regarding the impact. This study fills this gap by examining the influence of digital capabilities on entrepreneurial performance and advocates for increased SME investment in digital transformation. Analyzing data from 313 SME managers, the results reveal that digital capabilities substantially boost performance, with opportunity capability serving as a critical mediator. Additionally, entrepreneurial leadership strengthens the connection between digital fluency, opportunity capability, and performance. This research highlights the necessity of integrating digital capabilities, opportunity capability, and entrepreneurial leadership to optimize business outcomes, providing practical insights for SMEs to formulate effective digital transformation strategies.

In today's rapidly evolving business environment, Digital Transformation (DT) has become essential for enterprise development and innovation, significantly impacting corporate performance (Elia et al., 2020; Hanelt et al., 2021). DT enables businesses to adapt to technological advancements, improve operational efficiency, and enhance global competitiveness (Nambisan, 2017). As companies navigate the Fourth Industrial Revolution, developing strong digital capabilities is vital for survival and growth (Levallet & Chan, 2019). Consequently, businesses must not only adopt new technologies but also integrate them into their core strategies and operations (Cannas, 2021; Kim & Kim, 2023).

However, these advantages come with significant challenges that make DT implementation arduous for many companies (Levallet & Chan, 2019). The process requires substantial resources, incurs high costs, and involves the complexity of integrating new technologies into existing systems (Cannas, 2021). Organizations often encounter difficulties in aligning their traditional processes with digital innovations while managing risks and ensuring a return on investment (Liu et al., 2011; Peng & Tao, 2022). Furthermore, the rapid pace of technological change necessitates that companies continually update their digital capabilities to stay competitive. Additionally, transforming organizational culture to support digital initiatives presents a considerable challenge.

These challenges are even more pronounced for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which typically operate with limited resources and capabilities (Ghobakhloo & Iranmanesh, 2021). SMEs may lack the necessary infrastructure, financial capital, and technical expertise to effectively adopt advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), big data analytics, and the Internet of Things (IoT). The complexity of the DT process strains their limited resources, making it difficult to attain successful outcomes (Crupi et al., 2020; Ramdani et al., 2021; Kim & Ahn, 2024). Moreover, SMEs often face significant uncertainty regarding the potential return on digital investments, which can deter them from engaging in such initiatives. The absence of tailored guidance and support further compounds these issues, leaving SMEs disadvantaged in the digital economy.

Previous research on DT has predominantly focused on large enterprises, leaving a gap in understanding its impact on SMEs (Ghezzi & Cavallo, 2020; Khin & Ho, 2019). This scarcity of SME-specific studies leads smaller firms to question the benefits of investing in DT for their business. The absence of clear guidelines and best practices tailored to SMEs results in uncertainties and hesitations in pursuing DT initiatives. Without tangible evidence of the advantages and a clear roadmap for implementation, SMEs may persist with outdated technologies, missing out on opportunities for growth and competitiveness. There is a pressing need for research that addresses the unique challenges faced by SMEs in the digital transformation journey.

This study aims to bridge a gap by exploring the impact of digital capability on entrepreneurial performance in SMEs. By analyzing how digital capability influences entrepreneurial performance through opportunity capability and entrepreneurial leadership, it provides organizations with insights to effectively enhance their digital capabilities. Understanding the mediating role of opportunity capability can enable SMEs to leverage digital resources to identify and exploit new business opportunities, thereby transforming technological investments into tangible market advantages (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000). Furthermore, examining the moderating role of entrepreneurial leadership illuminates how leadership styles can influence the successful integration of digital technologies (Baron, 2008; Murnieks et al., 2014; Cardon et al., 2009). This approach facilitates the development of better-designed support measures and resource allocation methods, offering corporate executives a solid foundation for capital investment and decision-making.

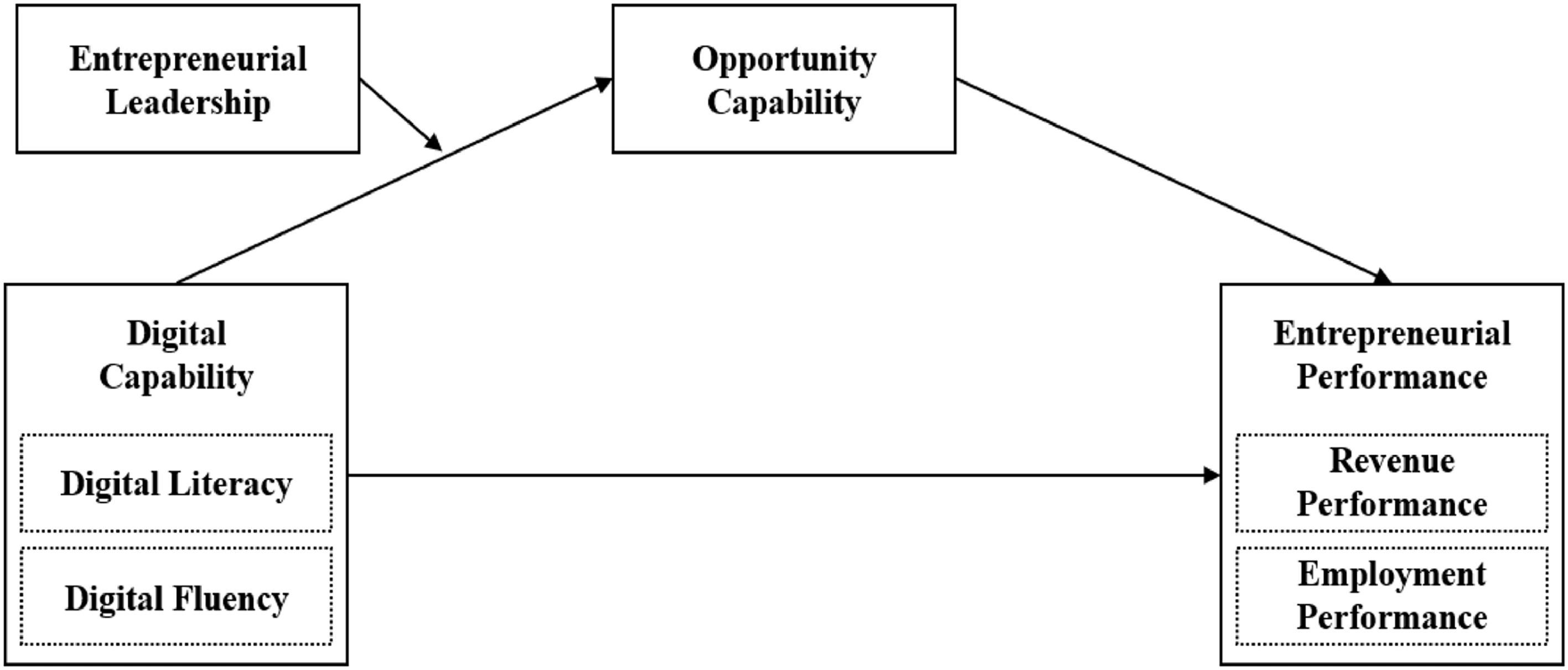

This study underscores the importance of digital capability for SMEs and enhances understanding of its relationship with entrepreneurial performance. By highlighting the roles of opportunity capability and entrepreneurial leadership, the research promotes the active development of digital capabilities within SMEs. Through this, it aims to provide useful guidelines for implementing effective digital transformation strategies in a rapidly changing market environment. To achieve these objectives, the study proposes a conceptual model that illustrates the relationships among digital capability, opportunity capability, entrepreneurial leadership, and entrepreneurial performance in SMEs (See Fig. 1). This model serves as a framework for understanding how these factors interrelate and influence one another, providing a basis for empirical investigation and practical application. The following section introduces this conceptual model detailing the theories and hypotheses.

Theory and hypotheses developmentDigital capabilities, entrepreneurial performance and opportunity capabilityIn the digital era, as management practices, customer demands, competitor activities, and market policies become increasingly digitized, data has emerged as a crucial strategic resource. The theory of dynamic capabilities suggests that these capabilities enable firms to identify opportunities and secure resources, which are crucial for gaining a competitive advantage and enhancing performance (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Winter, 2003). Digital capabilities, a type of dynamic capability, empower firms to innovate and adapt quickly to environmental changes, thus improving overall performance (Wilden et al., 2013). Through the integration of digital technologies into business strategies and operations, firms can optimize resource allocation, enhance efficiency in information retrieval, and transform opportunities into new business ventures, ultimately boosting firm performance (Zahra et al., 2006; Sousa-Zomer et al., 2020).

This study further disaggregates digital capabilities into two primary components: digital literacy and digital fluency, each playing a crucial role in enhancing a firm's opportunity capability (Nambisan, 2017). Digital literacy includes the ability to understand and utilize digital information and technologies, enabling firms to effectively acquire, manage, and analyze market data (Glister, 1997; Martin, 2008). This capability enhances decision-making, responsiveness to market changes, and the ability to meet customer demands, thereby contributing to increased profitability. Digital fluency, on the other hand, extends beyond basic digital knowledge to include the ability to apply, innovate, and adapt digital tools, platforms, and strategies (Pham et al., 2017; Wei et al., 2020). Firms with high digital fluency can optimize operations, reduce errors and costs, and indirectly boost profitability. Such organizations rapidly adopt emerging technologies, innovate products or services, develop new revenue streams, and enhance market competitiveness.

In summary, digital capabilities help firms identify market trends and consumer preferences, make informed decisions, foster innovation, and optimize services. These capabilities facilitate the integration of digital tools, improve team efficiency, create a flexible and innovative work environment, and contribute to talent acquisition and retention (Huhtala et al., 2014).

H1

Digital capability positively impacts entrepreneurial performance.

H1a

Digital literacy positively impacts revenue performance.

H1b

Digital literacy positively impacts employment performance.

H1c

Digital fluency positively impacts revenue performance.

H1d

Digital fluency positively impacts employment performance.

Additionally, firms with strong digital capabilities excel at using digital technologies to identify and capitalize on business opportunities (Mostafiz et al., 2019, 2021). These firms employ digital tools to track changes in customer demand, competitor actions, and technological advancements. They collect and integrate market information to underpin opportunity identification, evaluation, and development (Soluk et al., 2021).

H2

Digital capability positively impacts opportunity capability.

H2a

Digital literacy positively impacts opportunity capability.

H2b

Digital fluency positively impacts opportunity capability.

Opportunity capability plays a pivotal role in firm performance (Ardichvili et al., 2003). The processes of identifying, evaluating, and applying opportunities are crucial for the establishment, survival, and growth of new ventures, significantly enhancing performance outcomes (Mostafiz et al., 2019).

H3

Opportunity capability positively impacts entrepreneurial performance.

H3a

Opportunity capability positively impacts revenue performance.

H3b

Opportunity capability positively impacts employment performance.

The mediating role of opportunity capabilityThe rapid advancement in digital technology has significantly transformed the business landscape, requiring organizations to possess strong digital capabilities to succeed. These capabilities allow firms to efficiently integrate digital and entrepreneurial resources, seize opportunities, gather information, comprehend user needs, mitigate risks, and reduce both time and costs associated with the development of new products and technologies, thereby fostering sustainable development (Nambisan, 2017). In a complex and uncertain business environment, entrepreneurs and their teams frequently encounter difficulties in precisely identifying and managing business opportunities, potentially resulting in inefficient resource use.

Digital technologies have revolutionized traditional methods of information exchange and knowledge distribution, making the identification and development of fragmented business opportunities essential for success (Wu et al., 2021). Opportunity capability is crucial as it enables organizations to evaluate and develop opportunities, assess the viability and profitability of new ventures, and efficiently allocate resources to enhance performance (Shu et al., 2018). This capability spans the entire process from opportunity recognition to utilization and serves as a vital link between digital capability and firm performance (Mostafiz et al., 2019).

Enhanced digital capability allows organizations to better recognize market and technological trends, identify more business opportunities, and leverage these opportunities through technological innovation and strategic application, thereby enhancing performance (Yoo & Kim, 2019). The mediating role of opportunity capability is critical in linking digital capabilities to entrepreneurial performance. It increases the effectiveness of digital literacy and fluency in enhancing revenue and employment outcomes by facilitating the recognition and exploitation of business opportunities.

H4

Opportunity capability mediates the relationship between digital capability and entrepreneurial performance.

H4a

Opportunity capability mediates the relationship between digital literacy and revenue performance.

H4b

Opportunity capability mediates the relationship between digital literacy and employment performance.

H4c

Opportunity capability mediates the relationship between digital fluency and revenue performance.

H4d

Opportunity capability mediates the relationship between digital fluency and employment performance.

The proposed hypotheses emphasize the importance of developing opportunity capability within organizations to fully capitalize on the benefits of digital transformation. By enhancing digital capabilities, firms can improve their ability to recognize and leverage business opportunities, thereby driving entrepreneurial performance and achieving sustainable growth (Westerman & Bonnet, 2015; Gökalp & Martinez, 2021). This approach not only supports the identification and exploitation of opportunities but also strengthens strategic decision-making and resource allocation, leading to enhanced organizational outcomes (Mostafiz et al., 2019).

The moderating effect of entrepreneurial leadershipEntrepreneurial leadership is defined by a leader's efforts to discover and create new strategic value, utilizing their skills and motivating employees to achieve organizational goals and drive innovation. Leaders who embody entrepreneurial leadership excel at identifying and creating new opportunities and ventures compared to others (Gupta et al., 2004). This opportunity-centric behavior enables organizational recognition and exploitation of emerging opportunities, inspiring team members to partake in innovative activities (Cunningham & Lischeron, 1991). Such leadership cultivates a culture that encourages innovation, ultimately enhancing the organization's digital capabilities and promoting the adoption and effective use of digital technologies (Chen et al., 2007).

Renko et al. (2015) posited that entrepreneurial leadership plays a crucial role in fostering an innovative organizational environment, encouraging employees to move away from traditional work methods and focus on entrepreneurial activities. This approach not only stimulates innovation, motivation, and creativity but also promotes internal learning and knowledge sharing. Consequently, team members are more inclined to utilize digital technologies for identifying and developing business opportunities, thereby enhancing digital capabilities and improving the quality and efficiency of opportunity development. Furthermore, entrepreneurial leadership affects resource allocation and strategic execution, ensuring resources are effectively channeled to enhance digital capabilities and align with identified opportunities (Hmieleski & Ensley, 2007).

In essence, entrepreneurial leadership plays a crucial role in directing the organization toward opportunity-focused activities, thereby increasing engagement and proactivity in opportunity recognition and development. It exerts a sustained positive influence on digital capabilities, serving as a moderating factor in the relationship between digital capability and opportunity capability. This moderation is notably significant in utilizing digital technologies to capture and exploit new opportunities within a competitive market environment.

H5

The positive impact of digital capability on entrepreneurial performance, mediated by opportunity capability, is stronger at higher levels of entrepreneurial leadership.

H5a

The positive impact of digital literacy on revenue growth, mediated by opportunity capability, is stronger at higher levels of entrepreneurial leadership.

H5b

The positive impact of digital literacy on employment growth, mediated by opportunity capability, is stronger at higher levels of entrepreneurial leadership.

H5c

The positive impact of digital fluency on revenue growth, mediated by opportunity capability, is stronger at higher levels of entrepreneurial leadership.

H5d

The positive impact of digital fluency on employment growth, mediated by opportunity capability, is stronger at higher levels of entrepreneurial leadership.

Research methodData collection and sample characteristicsIn this study, data were collected through a comprehensive survey aimed at exploring key aspects of firms' digital capabilities, opportunity recognition abilities, entrepreneurial performance, and managerial entrepreneurial leadership. The survey was conducted online, targeting directors well-positioned to provide detailed and accurate information about their company's situation, yielding a total of 313 valid responses.

In terms of firm size, the sample aligned with the widely accepted definition of SMEs, encompassing micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises to provide a comprehensive perspective. Specifically, the sample included firms with employee counts ranging from fewer than 10 to a maximum of 200, representing a broad spectrum within the small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) category. Given the primary objective of this study, which is to explore the necessity of digital transformation for firms with extremely limited resources, a particular emphasis was placed on micro and small enterprises within the SME category.

Specifically, the sample consisted of 11 companies with fewer than 10 employees (representing 3.5 percent of the sample), 81 companies with 11–20 employees (25.9 percent), 109 companies with 21–50 employees (34.8 percent), and 79 companies with 51–100 employees (25.2 percent), with only 33 companies having more than 100 employees (10.5 percent). This distribution underscores our intention to examine in depth the digital transformation challenges and opportunities encountered by smaller firms, which often operate with more limited resources.

In terms of firm age, our sample spanned a wide range of operational histories, from newly established startups to well-established firms with decades of experience. Specifically, it included 12 companies with less than 3 years of operation (3.8 percent), 52 companies operating for 3–5 years (16.6 percent), 101 companies with a history of 5–10 years (32.3 percent), 105 companies with 10–20 years (33.5 percent), and 43 companies with over 20 years of operation (13.7 percent). This variety ensures that the study provides insights into how digital transformation needs and entrepreneurial dynamics evolve at different stages of firm maturity.

Moreover, this study aimed to comprehensively analyze the impact of digital capabilities on firm performance across various industries, sizes, ages, and R&D investment ratios. The participating companies spanned manufacturing, IT, service, and retail sectors. Specifically, there were 66 manufacturing firms (21.1 percent), 96 IT firms (30.7 percent), 90 service firms (28.8 percent), and 61 retail firms (19.5 percent). Regarding R&D investment ratio, the sample included firms with a broad spectrum of investment ratios from less than 5 percent to over 20 percent. Specifically, there were 27 firms investing less than 5 percent in R&D (8.6 percent), 90 firms investing 5–10 percent (28.8 percent), 93 firms investing 10–15 percent (29.7 percent), 67 firms investing 15–20 percent (21.4 percent), and 36 firms investing more than 20 percent (11.5 percent).

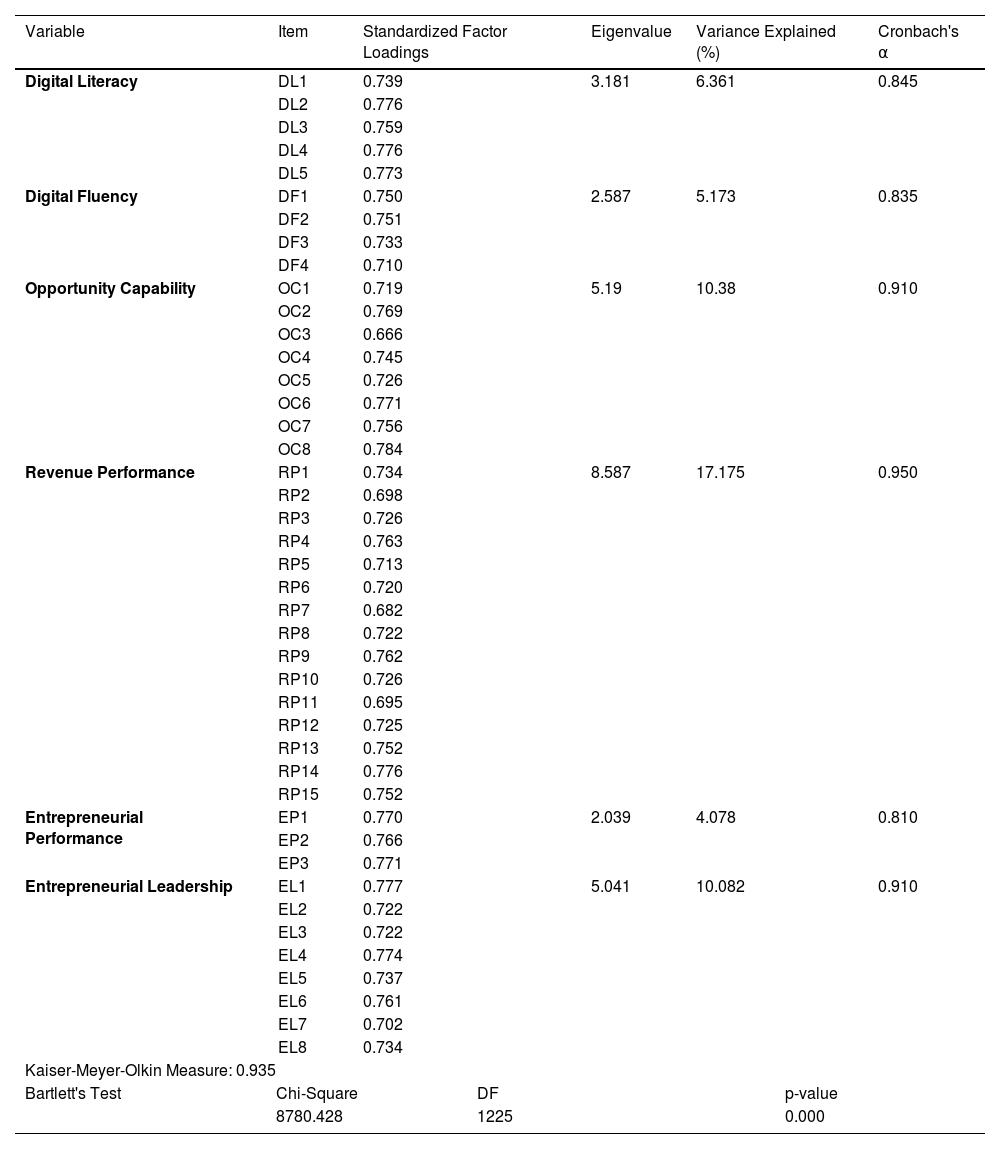

Exploratory factor analysisIn this study, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was employed initially to identify the underlying factor structure of the variables gathered from the survey data. EFA is particularly beneficial when the relationships between variables are unestablished or when the aim is to explore potential dimensions within the dataset. By analyzing the correlation patterns among the observed variables, EFA facilitated the uncovering of latent constructs that might not be readily visible. This process enabled the categorization of different survey items into groups, ensuring alignment with the theoretical framework of this study.

The analysis used principal axis factoring and varimax rotation methods (See Table 1). Consequently, a total of six factors were extracted, detailed as follows: The first factor, Digital Literacy, exhibited an eigenvalue of 3.181 and accounted for 6.361 percent of the variance. This factor's item loadings ranged between 0.739 and 0.776, and the Cronbach's α was 0.845, indicating high reliability. The second factor, Digital Fluency, with an eigenvalue of 2.587, explained 5.175 percent of the variance. Its loadings varied from 0.710 to 0.751, accompanied by a Cronbach's α of 0.835, also demonstrating high reliability. The third factor, Opportunity Capability, presented an eigenvalue of 5.19 and explained 10.369 percent of the variance. Item loadings for this factor varied from 0.669 to 0.784, and Cronbach's α was 0.910, signifying very high reliability. The fourth factor, Revenue Performance, with an eigenvalue of 8.587, explained 17.175 percent of the variance. Its item loadings ranged from 0.682 to 0.862, and Cronbach's α was 0.950, indicating the highest reliability. The fifth factor, Entrepreneurial Performance, had an eigenvalue of 2.039 and accounted for 4.078 percent of the variance. Its loadings fluctuated from 0.766 to 0.774, with a Cronbach's α of 0.810. The final factor, Entrepreneurial Leadership, presented an eigenvalue of 5.041 and explained 10.082 percent of the variance. This factor's loadings ranged from 0.722 to 0.772, and its Cronbach's α was 0.910, indicating high reliability. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.935, showing the data were highly suitable for factor analysis. Bartlett's test of sphericity yielded a chi-square value of 8780.428 with a significance level of p < 0.001, confirming the factor model's appropriateness.

Exploratory factor analysis.

| Variable | Item | Standardized Factor Loadings | Eigenvalue | Variance Explained (%) | Cronbach's α | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Literacy | DL1 | 0.739 | 3.181 | 6.361 | 0.845 | |||

| DL2 | 0.776 | |||||||

| DL3 | 0.759 | |||||||

| DL4 | 0.776 | |||||||

| DL5 | 0.773 | |||||||

| Digital Fluency | DF1 | 0.750 | 2.587 | 5.173 | 0.835 | |||

| DF2 | 0.751 | |||||||

| DF3 | 0.733 | |||||||

| DF4 | 0.710 | |||||||

| Opportunity Capability | OC1 | 0.719 | 5.19 | 10.38 | 0.910 | |||

| OC2 | 0.769 | |||||||

| OC3 | 0.666 | |||||||

| OC4 | 0.745 | |||||||

| OC5 | 0.726 | |||||||

| OC6 | 0.771 | |||||||

| OC7 | 0.756 | |||||||

| OC8 | 0.784 | |||||||

| Revenue Performance | RP1 | 0.734 | 8.587 | 17.175 | 0.950 | |||

| RP2 | 0.698 | |||||||

| RP3 | 0.726 | |||||||

| RP4 | 0.763 | |||||||

| RP5 | 0.713 | |||||||

| RP6 | 0.720 | |||||||

| RP7 | 0.682 | |||||||

| RP8 | 0.722 | |||||||

| RP9 | 0.762 | |||||||

| RP10 | 0.726 | |||||||

| RP11 | 0.695 | |||||||

| RP12 | 0.725 | |||||||

| RP13 | 0.752 | |||||||

| RP14 | 0.776 | |||||||

| RP15 | 0.752 | |||||||

| Entrepreneurial Performance | EP1 | 0.770 | 2.039 | 4.078 | 0.810 | |||

| EP2 | 0.766 | |||||||

| EP3 | 0.771 | |||||||

| Entrepreneurial Leadership | EL1 | 0.777 | 5.041 | 10.082 | 0.910 | |||

| EL2 | 0.722 | |||||||

| EL3 | 0.722 | |||||||

| EL4 | 0.774 | |||||||

| EL5 | 0.737 | |||||||

| EL6 | 0.761 | |||||||

| EL7 | 0.702 | |||||||

| EL8 | 0.734 | |||||||

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure: 0.935 | ||||||||

| Bartlett's Test | Chi-Square | DF | p-value | |||||

| 8780.428 | 1225 | 0.000 | ||||||

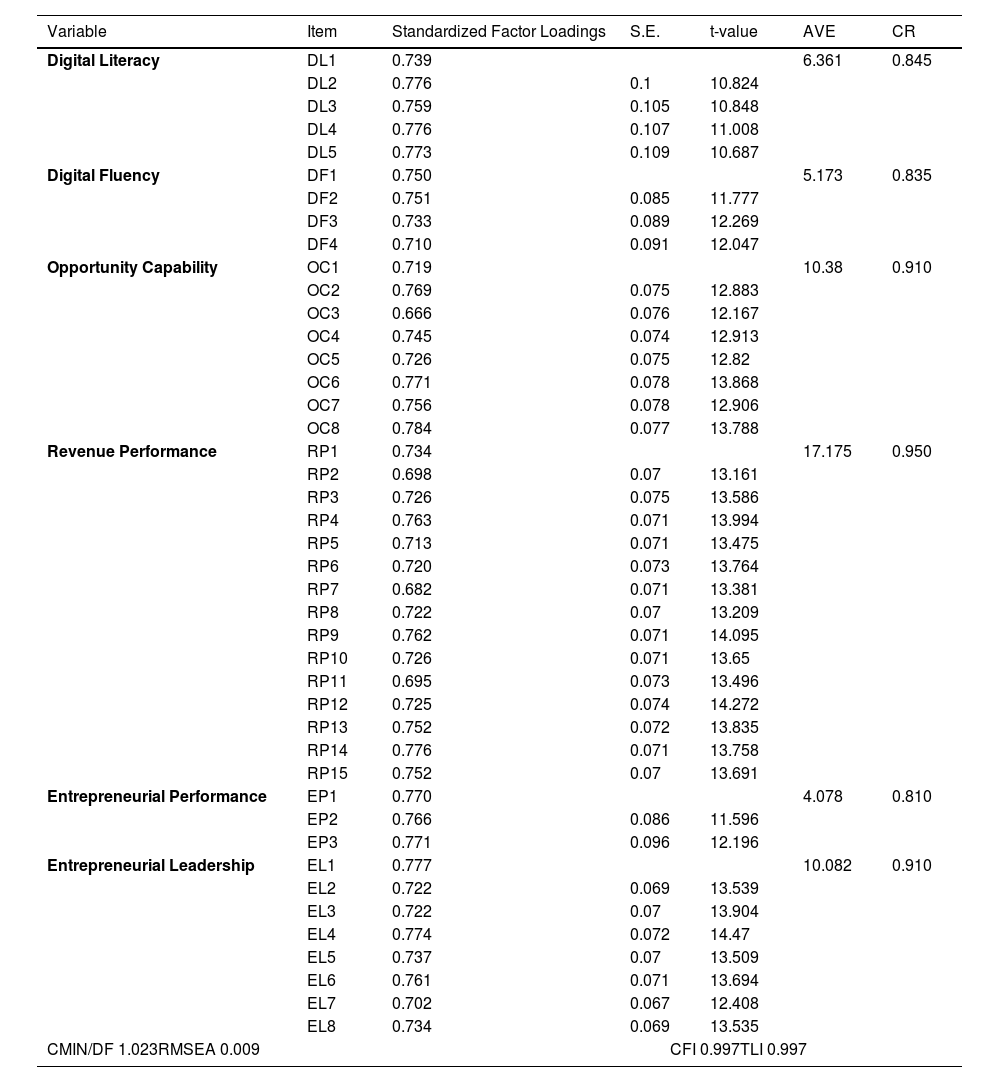

Building on the findings from the EFA, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to validate the factor structure previously identified (see Table 2). The purpose of the CFA was to test the hypothesized model by assessing whether the data fit the proposed structure, thereby confirming the accuracy and consistency of the identified factors. This step was essential in verifying the validity and reliability of the measurement model by providing statistical evidence that the observed variables adequately represented the theoretical constructs intended for this study. The use of CFA ensured that the factor structure met established criteria for model fit, thereby reinforcing the robustness of our findings.

Confirmatory factor analysis.

| Variable | Item | Standardized Factor Loadings | S.E. | t-value | AVE | CR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Literacy | DL1 | 0.739 | 6.361 | 0.845 | |||

| DL2 | 0.776 | 0.1 | 10.824 | ||||

| DL3 | 0.759 | 0.105 | 10.848 | ||||

| DL4 | 0.776 | 0.107 | 11.008 | ||||

| DL5 | 0.773 | 0.109 | 10.687 | ||||

| Digital Fluency | DF1 | 0.750 | 5.173 | 0.835 | |||

| DF2 | 0.751 | 0.085 | 11.777 | ||||

| DF3 | 0.733 | 0.089 | 12.269 | ||||

| DF4 | 0.710 | 0.091 | 12.047 | ||||

| Opportunity Capability | OC1 | 0.719 | 10.38 | 0.910 | |||

| OC2 | 0.769 | 0.075 | 12.883 | ||||

| OC3 | 0.666 | 0.076 | 12.167 | ||||

| OC4 | 0.745 | 0.074 | 12.913 | ||||

| OC5 | 0.726 | 0.075 | 12.82 | ||||

| OC6 | 0.771 | 0.078 | 13.868 | ||||

| OC7 | 0.756 | 0.078 | 12.906 | ||||

| OC8 | 0.784 | 0.077 | 13.788 | ||||

| Revenue Performance | RP1 | 0.734 | 17.175 | 0.950 | |||

| RP2 | 0.698 | 0.07 | 13.161 | ||||

| RP3 | 0.726 | 0.075 | 13.586 | ||||

| RP4 | 0.763 | 0.071 | 13.994 | ||||

| RP5 | 0.713 | 0.071 | 13.475 | ||||

| RP6 | 0.720 | 0.073 | 13.764 | ||||

| RP7 | 0.682 | 0.071 | 13.381 | ||||

| RP8 | 0.722 | 0.07 | 13.209 | ||||

| RP9 | 0.762 | 0.071 | 14.095 | ||||

| RP10 | 0.726 | 0.071 | 13.65 | ||||

| RP11 | 0.695 | 0.073 | 13.496 | ||||

| RP12 | 0.725 | 0.074 | 14.272 | ||||

| RP13 | 0.752 | 0.072 | 13.835 | ||||

| RP14 | 0.776 | 0.071 | 13.758 | ||||

| RP15 | 0.752 | 0.07 | 13.691 | ||||

| Entrepreneurial Performance | EP1 | 0.770 | 4.078 | 0.810 | |||

| EP2 | 0.766 | 0.086 | 11.596 | ||||

| EP3 | 0.771 | 0.096 | 12.196 | ||||

| Entrepreneurial Leadership | EL1 | 0.777 | 10.082 | 0.910 | |||

| EL2 | 0.722 | 0.069 | 13.539 | ||||

| EL3 | 0.722 | 0.07 | 13.904 | ||||

| EL4 | 0.774 | 0.072 | 14.47 | ||||

| EL5 | 0.737 | 0.07 | 13.509 | ||||

| EL6 | 0.761 | 0.071 | 13.694 | ||||

| EL7 | 0.702 | 0.067 | 12.408 | ||||

| EL8 | 0.734 | 0.069 | 13.535 | ||||

| CMIN/DF 1.023RMSEA 0.009 | CFI 0.997TLI 0.997 | ||||||

***p < 0.001.

**p < 0.01.

*p < 0.05.

CFA was utilized to assess the validity and reliability of the measurement model, and the results are as follows: The first factor, Digital Literacy, had standardized factor loadings ranging from 0.666 to 0.751, an average variance extracted (AVE) of 0.523, and a composite reliability (CR) of 0.845. The second factor, Digital Fluency, displayed standardized factor loadings ranging from 0.727 to 0.755, an AVE of 0.559, and a CR of 0.835. The third factor, Opportunity Capability, exhibited standardized factor loadings ranging from 0.701 to 0.789, an AVE of 0.558, and a CR of 0.910. The fourth factor, Revenue Performance, demonstrated standardized factor loadings ranging from 0.722 to 0.776, an AVE of 0.557, and a CR of 0.950, indicating the highest reliability. The fifth factor, Entrepreneurial Performance, had standardized factor loadings ranging from 0.736 to 0.821, an AVE of 0.588, and a CR of 0.810. The final factor, Entrepreneurial Leadership, presented standardized factor loadings ranging from 0.689 to 0.787, an AVE of 0.560, and a CR of 0.910, indicating high reliability.

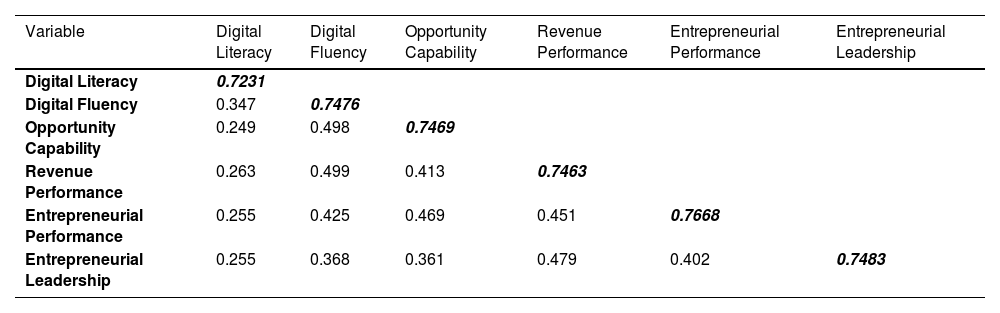

All factor loadings' t-values were statistically significant (p < 0.001, p < 0.01, p < 0.05), supporting the adequacy of the measurement model. Additionally, the AVE values exceeded 0.5, indicating adequate convergent validity, and the CR values were above 0.7, signaling high reliability. Furthermore, the results confirmed that all constructs in this study met the criteria for discriminant validity (See Table 3), demonstrating that each construct is distinct and independent. These results validate the reliability and consistency of the constructs employed in this study. Consequently, future research may employ this factor structure to conduct regression analyses to examine the impact of each factor on dependent variables.

Discriminant validity.

| Variable | Digital Literacy | Digital Fluency | Opportunity Capability | Revenue Performance | Entrepreneurial Performance | Entrepreneurial Leadership |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Literacy | 0.7231 | |||||

| Digital Fluency | 0.347 | 0.7476 | ||||

| Opportunity Capability | 0.249 | 0.498 | 0.7469 | |||

| Revenue Performance | 0.263 | 0.499 | 0.413 | 0.7463 | ||

| Entrepreneurial Performance | 0.255 | 0.425 | 0.469 | 0.451 | 0.7668 | |

| Entrepreneurial Leadership | 0.255 | 0.368 | 0.361 | 0.479 | 0.402 | 0.7483 |

In this study, we employed a comprehensive set of analytical techniques to rigorously test the proposed moderated mediation framework. We began with the classical causal steps method, as outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986), to examine the mediating effects by systematically evaluating the relationships among the independent, mediating, and dependent variables. This approach provided an initial understanding of the mediation pathways within our model. To enhance the robustness of our findings, we augmented this analysis with the bootstrapping technique recommended by Preacher and Hayes (2008), which facilitated the estimation of indirect effects and the construction of confidence intervals. This procedure allowed for more precise estimates of the indirect effects, thereby increasing the statistical power and reliability of our mediation analysis.

Prior to conducting regression analyses, we performed rigorous checks of standardized residuals versus predicted values and examined the normal probability plot of standardized residuals, confirming the absence of significant violations of regression assumptions. Additionally, to mitigate potential multicollinearity issues when testing moderating hypotheses, all continuous variables were mean-centered (Aiken et al., 1991). Post-regression analysis confirmed that multicollinearity was not a concern, with the highest Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) value being 1.415, which is well within acceptable limits.

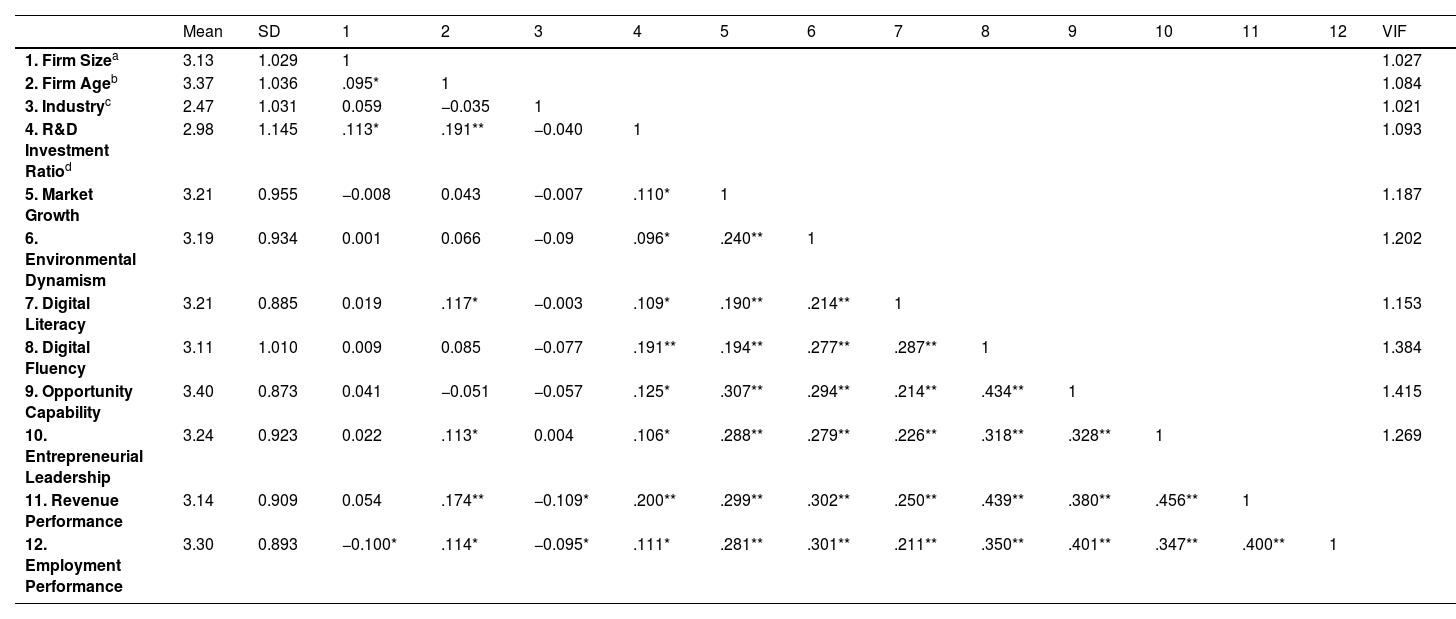

Lastly, a detailed descriptive statistical analysis was conducted to understand the characteristics of the data, including means, standard deviations, and correlations among the study variables. The descriptive statistics presented in Table 4 provided foundational insights into the relationships between variables and informed subsequent analyses. This integrated application of multiple analytical techniques ensured a robust and reliable foundation for interpreting the study results.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis.

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Firm Sizea | 3.13 | 1.029 | 1 | 1.027 | |||||||||||

| 2. Firm Ageb | 3.37 | 1.036 | .095* | 1 | 1.084 | ||||||||||

| 3. Industryc | 2.47 | 1.031 | 0.059 | −0.035 | 1 | 1.021 | |||||||||

| 4. R&D Investment Ratiod | 2.98 | 1.145 | .113* | .191** | −0.040 | 1 | 1.093 | ||||||||

| 5. Market Growth | 3.21 | 0.955 | −0.008 | 0.043 | −0.007 | .110* | 1 | 1.187 | |||||||

| 6. Environmental Dynamism | 3.19 | 0.934 | 0.001 | 0.066 | −0.09 | .096* | .240** | 1 | 1.202 | ||||||

| 7. Digital Literacy | 3.21 | 0.885 | 0.019 | .117* | −0.003 | .109* | .190** | .214** | 1 | 1.153 | |||||

| 8. Digital Fluency | 3.11 | 1.010 | 0.009 | 0.085 | −0.077 | .191** | .194** | .277** | .287** | 1 | 1.384 | ||||

| 9. Opportunity Capability | 3.40 | 0.873 | 0.041 | −0.051 | −0.057 | .125* | .307** | .294** | .214** | .434** | 1 | 1.415 | |||

| 10. Entrepreneurial Leadership | 3.24 | 0.923 | 0.022 | .113* | 0.004 | .106* | .288** | .279** | .226** | .318** | .328** | 1 | 1.269 | ||

| 11. Revenue Performance | 3.14 | 0.909 | 0.054 | .174** | −0.109* | .200** | .299** | .302** | .250** | .439** | .380** | .456** | 1 | ||

| 12. Employment Performance | 3.30 | 0.893 | −0.100* | .114* | −0.095* | .111* | .281** | .301** | .211** | .350** | .401** | .347** | .400** | 1 |

The analysis results for the proposed moderated mediation framework are presented in this section. Table 4 includes the descriptive statistics and correlation analysis for the model variables, which provide an initial understanding of data distribution and the relationships among key constructs. Detailed in Supplementary material, the regression analyseswere conducted to explore the mediating role of Opportunity Capability in the connection between digital competence (Digital Literacy and Digital Fluency) and entrepreneurial performance (Revenue Performance and Employment Performance). The analyses employed a sequential procedure, progressively incorporating control variables, independent variables (Digital Literacy and Digital Fluency), the mediating variable (Opportunity Capability), and the dependent variables to gauge their impacts.

The results indicate that Digital Literacy significantly enhances Revenue Performance (Model 1: β=0.143, t = 2.695, p < 0.01) and Employment Performance (Model 4: β=0.115, t = 2.131, p < 0.05). Similarly, Digital Fluency significantly boosts Revenue Performance (Model 7: β=0.334, t = 6.477, p < 0.001) and Employment Performance (Model 10: β=0.253, t = 4.679, p < 0.001). These findings support Hypotheses 1a, 1b, 1c, and 1d, confirming that both aspects of digital competence contribute to superior entrepreneurial performance. Additionally, the analysis shows that Digital Literacy (Model 2: β=0.129, t = 2.389, p < 0.05) and Digital Fluency (Model 8: β=0.353, t = 6.788, p < 0.001) significantly enhance Opportunity Capability, supporting Hypotheses 2a and 2b. These outcomes suggest that firms with higher digital competence are more likely to develop robust Opportunity Capability, which in turn plays a crucial role in their entrepreneurial success. Opportunity Capability demonstrated a significant positive impact on both Revenue Performance and Employment Performance. Specifically, in Model 3 (β=0.259, t = 4.771, p < 0.001), Model 6 (β=0.306, t = 5.582, p < 0.001), Model 9 (β=0.173, t = 3.104, p < 0.01), and Model 12 (β=0.256, t = 4.448, p < 0.001), the influence of Opportunity Capability on entrepreneurial performance is confirmed, thus supporting Hypotheses 3a and 3b.

The mediating role of Opportunity Capability was further assessed by examining how the relationship between digital competence and entrepreneurial performance altered when Opportunity Capability was included in the models. After introducing Opportunity Capability in Model 3, the direct impact of Digital Literacy on Revenue Performance decreased from β=0.129 (p < 0.05) to β=0.110 (p < 0.05), indicating that Opportunity Capability partially mediates this relationship, thus supporting Hypothesis 4a. In contrast, when Opportunity Capability was incorporated in Model 6, the effect of Digital Literacy on Employment Performance diminished from β=0.115 (p < 0.05) to an insignificant β=0.076 (p > 0.05), suggesting a full mediating effect and affirming Hypothesis 4b. Likewise, the inclusion of Opportunity Capability in Models 9 and 12 reduced the impact on Revenue Performance from β=0.334 (p < 0.001) to β=0.272 (p < 0.001) and on Employment Performance from β=0.253 (p < 0.001) to β=0.162 (p < 0.01), respectively. These reductions illustrate a partial mediating effect by Opportunity Capability, supporting Hypotheses 4c and 4d

Overall, these results confirm that Opportunity Capability significantly mediates the relationship between digital competence (both Digital Literacy and Digital Fluency) and entrepreneurial performance, impacting both revenue and employment outcomes. This finding underscores the importance of developing Opportunity Capability to optimize the positive effects of digital competencies on entrepreneurial success.

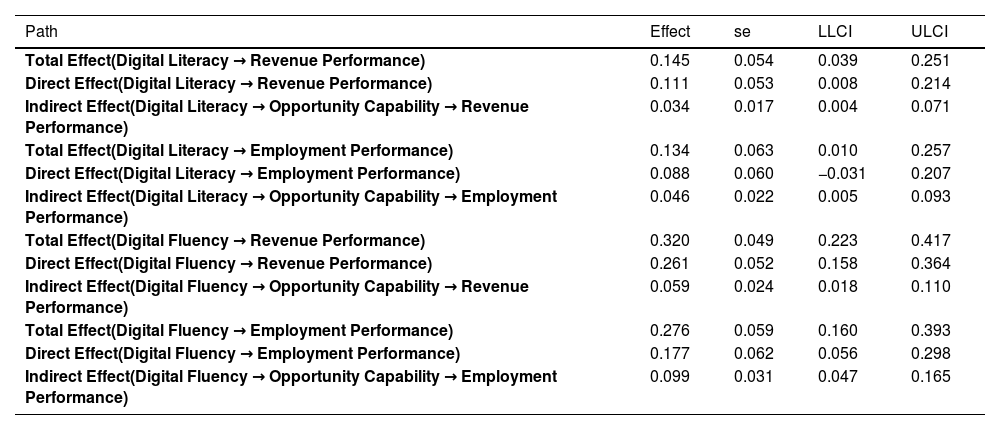

Table 5 displays the bootstrap confidence interval test results for total, direct, and indirect effects derived using Process 4.2. The total effects of Digital Literacy on Revenue Performance (Effect=0.145, CI=0.039∼0.251) and Employment Performance (Effect=0.134, CI=0.010∼0.257), and Digital Fluency on Revenue Performance (Effect=0.320, CI=0.223∼0.417) and Employment Performance (Effect=0.276, CI=0.160∼0.393) are all significant. The indirect effects, 'Digital Literacy → Opportunity Capability → Revenue Performance' (Effect=0.034, CI=0.004∼0.071), 'Digital Literacy → Opportunity Capability → Employment Performance' (Effect=0.046, CI=0.005∼0.093), 'Digital Fluency → Opportunity Capability → Revenue Performance' (Effect=0.059, CI=0.018∼0.110), and 'Digital Fluency → Opportunity Capability → Employment Performance' (Effect=0.099, CI=0.047∼0.165) are also statistically significant.

Bootstrap confidence interval test for indirect (mediation) effects.

| Path | Effect | se | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Effect(Digital Literacy → Revenue Performance) | 0.145 | 0.054 | 0.039 | 0.251 |

| Direct Effect(Digital Literacy → Revenue Performance) | 0.111 | 0.053 | 0.008 | 0.214 |

| Indirect Effect(Digital Literacy → Opportunity Capability → Revenue Performance) | 0.034 | 0.017 | 0.004 | 0.071 |

| Total Effect(Digital Literacy → Employment Performance) | 0.134 | 0.063 | 0.010 | 0.257 |

| Direct Effect(Digital Literacy → Employment Performance) | 0.088 | 0.060 | −0.031 | 0.207 |

| Indirect Effect(Digital Literacy → Opportunity Capability → Employment Performance) | 0.046 | 0.022 | 0.005 | 0.093 |

| Total Effect(Digital Fluency → Revenue Performance) | 0.320 | 0.049 | 0.223 | 0.417 |

| Direct Effect(Digital Fluency → Revenue Performance) | 0.261 | 0.052 | 0.158 | 0.364 |

| Indirect Effect(Digital Fluency → Opportunity Capability → Revenue Performance) | 0.059 | 0.024 | 0.018 | 0.110 |

| Total Effect(Digital Fluency → Employment Performance) | 0.276 | 0.059 | 0.160 | 0.393 |

| Direct Effect(Digital Fluency → Employment Performance) | 0.177 | 0.062 | 0.056 | 0.298 |

| Indirect Effect(Digital Fluency → Opportunity Capability → Employment Performance) | 0.099 | 0.031 | 0.047 | 0.165 |

Table 5 indicates that the direct effect of Digital Literacy on Employment Performance is no longer significant, suggesting that Opportunity Capability fully mediates the relationship between Digital Literacy and Employment Performance. This implies that while Digital Literacy is crucial in a digital environment, Opportunity Capability plays a more pivotal and critical role in Employment Performance. Companies with high Opportunity Capability offer broader development opportunities for employees, leading to greater competitiveness and potential for growth, thereby fostering a stable development environment that encourages employee retention. As a result, to improve employee satisfaction and loyalty and to decrease turnover rates, companies should prioritize and strengthen Opportunity Capability, integrating it with Digital Literacy to cultivate a more dynamic and competitive work environment.

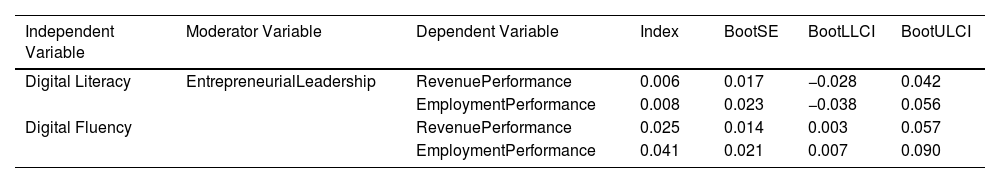

Furthermore, the results presented in Table 6 illustrate the moderated mediation effects of entrepreneurial leadership on the relationship between digital literacy and digital fluency, and performance outcomes such as profitability and employment performance. For digital literacy, the moderated mediation effects on profitability and employment performance yielded index values of 0.006 and 0.008, respectively. However, the inclusion of 0 in the confidence intervals indicates that these effects are not statistically significant, suggesting that opportunity capability fully mediates the relationship between digital literacy and employment performance. Conversely, for digital fluency, the index values of the moderated mediation effects on profitability and employment performance are 0.025 and 0.041, respectively, and the absence of 0 in the confidence intervals indicates statistical significance, implying a significant moderating role of entrepreneurial leadership. Thus, Hypotheses 5c and 5d are supported, whereas Hypotheses 5a and 5b are rejected.

Moderated mediation effect with digital literacy as an independent variable.

| Independent Variable | Moderator Variable | Dependent Variable | Index | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Literacy | EntrepreneurialLeadership | RevenuePerformance | 0.006 | 0.017 | −0.028 | 0.042 |

| EmploymentPerformance | 0.008 | 0.023 | −0.038 | 0.056 | ||

| Digital Fluency | RevenuePerformance | 0.025 | 0.014 | 0.003 | 0.057 | |

| EmploymentPerformance | 0.041 | 0.021 | 0.007 | 0.090 |

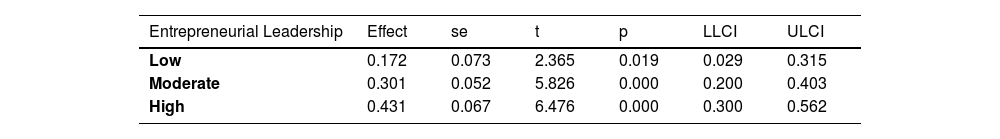

Table 7 delineates the moderating effects of various levels of entrepreneurial leadership (low, moderate, high) on the relationship between the independent and dependent variables. The results reveal that at a low level of entrepreneurial leadership, the effect value is 0.172, with a statistically significant p-value of 0.019. At a moderate level, the effect increases to 0.301, with a highly significant p-value of 0.000. At a high level, the effect value escalates to 0.431, with a p-value of 0.000, indicating a very strong and statistically significant relationship. In every scenario, the confidence intervals (LLCI and ULCI) exclude zero, confirming the significant moderating role of entrepreneurial leadership. These findings emphasize that as the level of entrepreneurial leadership escalates, the relationship between the independent and dependent variables intensifies, highlighting the pivotal role of entrepreneurial leadership as a moderator.

Discussion and conclusionWith the rapid advancement of digital technologies, digital transformation has emerged as a key trend in corporate development. In the digital economy era, digitalization has transformed the basic components of corporate growth by reshaping traditional business logic using digital technologies in the processes of opportunity discovery and resource acquisition among others. Therefore, digital competence is crucial for companies seeking to boost their digital transformation and overall performance, as it facilitates insights into various business operations, shifts in customer demand, competitor actions, and market policy implementations.

Paradoxically, developing digital competence demands considerable effort, making the efficiency of input versus output critical, particularly for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) with constrained resources. Despite recognizing the importance of digital transformation, many SMEs are reluctant to invest due to uncertainties about the direct impact of digital competence on business performance. Specifically, there is a scarcity of clear guidance on how investments in digital competence can yield tangible returns and how to effectively translate digital capabilities into performance outcomes. Existing research offers conflicting results, suggesting that merely having advanced digital technologies and tools does not ensure business success and sustainable growth. Companies need to comprehend how to utilize digital capabilities to interact with the market environment, identify, evaluate, and exploit market opportunities to improve market share and performance. Nevertheless, current studies have not adequately explored how companies use digital capabilities to facilitate complex interactions between opportunities and resources and the influence of management in this context.

This study seeks to resolve these uncertainties by investigating the specific impacts of digital capabilities on entrepreneurial performance, thereby motivating SMEs to invest more vigorously in digital transformation. The study examines the relationship between digital capabilities and entrepreneurial performance, employing opportunity capability and entrepreneurial leadership as mediating and moderating variables, respectively, with a focus on SME managers. The study has produced several important findings.

Theoretical and managerial implicationsThis study makes several theoretical contributions to the field of digital transformation and entrepreneurship. Firstly, it enhances our understanding of how digital capabilities directly and indirectly impact entrepreneurial performance, especially within SMEs. By illustrating the mediating role of opportunity capability, this research enriches the existing literature on digital transformation, clarifying the process by which digital competencies lead to entrepreneurial outcomes. It underscores that simply possessing digital capabilities is not enough; firms must also have the capacity to identify, evaluate, and act on opportunities to realize significant performance improvements. Secondly, the moderating role of entrepreneurial leadership, particularly in augmenting the effect of digital fluency on performance, introduces a new aspect to the discussions on leadership in digital transformation. This finding highlights that leadership styles that foster innovation and proactive behavior are essential in maximizing the benefits of digital fluency within SMEs. By synthesizing these concepts, this study contributes to a more comprehensive theoretical framework that delineates how digital competence, opportunity capability, and entrepreneurial leadership interplay to influence entrepreneurial performance.

From a practical perspective, the findings of this study provide vital insights for SME managers facing the challenges of digital transformation. The positive influence of digital capabilities on entrepreneurial performance indicates that SMEs should prioritize investing in digital literacy and fluency to stay competitive. Managers should proactively enhance digital skills at all organizational levels, ensuring that employees can effectively utilize digital tools. Additionally, the role of opportunity capability as a mediator suggests that possessing digital capabilities alone is inadequate; firms must develop systems and processes that facilitate the identification and exploitation of opportunities. Consequently, SMEs should invest in training programs that boost employees’ ability to recognize market opportunities, adapt to changing consumer demands, and utilize digital tools for strategic decision-making. Lastly, the moderating effect of entrepreneurial leadership highlights the importance of fostering leadership qualities that promote innovation and digital fluency among employees. Managers should cultivate an entrepreneurial mindset, encouraging risk-taking and creativity, thus improving their teams' ability to transform digital capabilities into concrete entrepreneurial outcomes.

Limitations and future research suggestionsDespite its contributions, this study has several limitations that warrant acknowledgment. First, the reliance on cross-sectional data restricts our understanding of the dynamic and evolving nature of digital transformation in SMEs. Since digital transformation is a continuous process, employing a longitudinal approach would offer deeper insights into the development and variation of digital and opportunity capabilities over time. Second, the study's sample was confined to SMEs within a specific geographic area, potentially limiting the findings' applicability to other contexts. Variations in industry, culture, and market environments could influence the observed relationships. Third, the focus was primarily on the mediating role of opportunity capability and the moderating role of entrepreneurial leadership, which may overlook other influential factors such as organizational culture, employee skills, and external environmental conditions.

To mitigate these limitations, future research should consider a longitudinal design to examine the evolution and impact of digital and opportunity capabilities on entrepreneurial performance across different stages of digital transformation. This approach would offer valuable insights into the dynamic nature of digital transformation and its long-term effects on business outcomes. Additionally, including SMEs from diverse industries and regions would improve the generalizability of the results and provide a broader perspective on the impact of digital capabilities. Further research might also explore other potential moderating or mediating variables, such as organizational culture, employee digital skills, or external market conditions, to develop a more nuanced understanding of how digital competencies lead to entrepreneurial success. Lastly, investigating how SMEs integrate digital capabilities with other strategic resources like innovation and collaboration networks could offer a comprehensive view of the pathways to digital transformation and sustained competitive advantage.

In summary, this study offers insights into how SMEs can enhance revenue and employment performance by improving digital literacy and digital fluency, highlighting the pivotal role of entrepreneurial leadership in this process. The findings provide significant guidelines for SMEs to effectively navigate digital transformation and achieve sustainable competitive advantages, enriching the understanding of digital transformation in SMEs and contributing to the theoretical foundations of related research.

CRediT authorship contribution statementJunic Kim: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Wenzheng Jin: Writing – original draft, Data curation.

This work was supported by Institute of Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) under the metaverse support program to nurture the best talents (IITP-2024-RS-2023–00256615) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT).