Research on the correlations between design leadership, work values and ethics, and workplace innovation is lacking, especially in non-Western regions. This study aimed to investigate the mediating role of design leadership in the relationship of work values and ethics with workplace innovation in Asian small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Five hypotheses were established to explore the proposed model. Data were obtained from 995 SMEs in Japan, Thailand, China, and Vietnam and were examined using partial least squares analysis. The findings indicated a correlation between work values and ethics and design leadership, with the latter influencing workplace innovation across its four dimensions. This demonstrated the significant association between work values and ethics and workplace innovation. Design leadership was also shown to fully mediate the relationship between work values and ethics and workplace innovation in Asian SMEs. This study provides a deeper understanding of the emerging literature on the associations of design leadership, work values and ethics, and workplace innovation. It emphasizes the importance of design leadership and its correlations with various aspects of workplace innovation and work values and ethics, which have not received adequate attention in the existing literature. Asian SME entrepreneurs can improve the innovation capabilities of their organizations by focusing on and implementing design leadership behaviors, which may thereby help their organizations establish a competitive advantage and promote long-term sustainability.

In today's competitive marketplaces, innovation is a critical component determining organizational success. The scientific evidence indeed argues that innovation is a significant attribute that assists small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in remaining competitive in the global marketplace (Casals, 2011; Davis & Bendickson, 2021; Mbizi, 2013; Rhee & Stephens, 2020). For example, Rhee and Stephens (2020) found that innovation-oriented technology significantly contributes to SMEs developing competitive advantages, leading to improved market share and sales growth. Meanwhile, changing market conditions, such as those imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, force smaller ventures to pivot or reinvent their businesses through new technology or unique value propositions (Vanhaverbeke et al., 2012). Being aware of the benefits of stimulating continuous innovation, organizations of all sizes seek ways to engage in constant innovation to sustain and often sharpen their competitive advantages (Matthews & Bucolo, 2013; Mohsen et al., 2021). At the same time, small ventures’ contributions to innovation-led growth and job creation have been strongly evident in recent years (Callan & Guinet, 2000). A large body of evidence shows that SMEs, especially younger ones, contribute sufficiently and increasingly with innovations by introducing new products and adapting existing products to customer needs (Callan & Guinet, 2000).

Previous studies have examined how specific leadership styles may propel organizational innovation. Iqbal and Piwowar-Sulej (2023) focused on sustainable leadership and its impact on frugal innovation through the mediating effect of knowledge sharing. The cited study found that sustainable leaders, with their consideration of employees, various other stakeholders, and the natural environment, enhance heterogeneous knowledge-sharing behaviors both within organizations and with external networks. The conclusion was that sustainable leadership bolsters frugal innovation by stimulating internal and external knowledge sharing. Xuecheng and Iqbal (2022) examined the effects of ethical leadership on environmental innovation, identifying that ethical leaders striving for sustainability and morality positively impacted firm environmental innovation and, in turn, improved firm sustainable performance.

The literature also identifies that leadership and innovation play key roles in improving SME performance (e.g. Jun et al., 2021; Sok et al., 2013), and that a manager's or entrepreneur's leadership behavior is a major factor influencing organizational innovation (Carneiro, 2008; Jung et al., 2008; Sidik, 2012). This is especially so for SMEs (vs. large firms) as they are dominated by entrepreneurs (Sidik, 2012). For example, the role of entrepreneurs in influencing innovation orientation in Norwegian SMEs was investigated by Colclough et al. (2019), who found that the growth ambitions of managers and entrepreneurs influenced their focus on different innovation types. Carneiro (2008) found that leadership contributes to increasing innovation efforts and positive innovation results within SMEs. Among Vietnamese SMEs, entrepreneur innovativeness and personality played crucial roles for innovation adoption, as did high-performance work systems for innovation and creativity (Do & Shipton, 2019; Marcati et al., 2008; Oeij et al., 2021).

Although the exploration of the relationship between leadership and innovation within SMEs has garnered significant scholarly attention, the contributions in the literature remain somewhat constrained to traditional forms of leadership. For example, there remains a notable gap regarding explorations into emerging leadership styles better aligned with the unique needs and dynamics of SMEs (Megheirkouni & Mejheirkouni, 2020; Rowley et al., 2021). This oversight is significant, as emerging leadership styles such as design leadership offer distinct advantages in terms of fostering a culture of creativity, collaboration, and experimentation (Hsieh et al., 2022; Lee & Cassidy, 2007)—qualities that are particularly important drivers of innovation in SMEs. Furthermore, the existing research has overlooked contributive factors to the development of emerging leadership styles, and has lacked interest in how an increased focus on work values and ethics (WVE) can lead to heightened design leadership and consequently drive innovation within SMEs. Still, the increasing emphasis on ethical principles and corporate social responsibility renders acquiring a clearer understanding of the relationship between WVE and leadership behaviors an imperative task. Since WVE are closely intertwined with the core responsibilities of design leaders, including envisioning the future and inspiring teams (Muenjohn & McMurray, 2017), investigations into whether organizational cultures promotive of WVE can foster design leadership qualities offer promising research avenues for unlocking the innovation potentials of SMEs.

To address these research gaps, this cross-national study aimed to elucidate the mechanisms by which WVE influence leadership behaviors and innovation outcomes in Asian SMEs. The current study is grounded in an individual-level leadership theory known as the dyadic process (Lussier & Achua, 2015). Using this theoretical framework, examinations unfold regarding the relationships among design leadership, WVE, and workplace innovation in the context of the possible mediation of leadership on the association of WVE with innovation in Asian SMEs. The research question is as follows: “What is the relationship among design leadership, WVE, and workplace innovation in Asian SMEs?”

These examinations hold relevance for both theory and practice on Asian SMEs, and deliver a fourfold contribution. First, it expands the existing literature on leadership and innovation by redirecting the research focus toward an emerging and under-researched leadership style known as design leadership. While previous studies underscored the distinct capabilities of design leadership in nurturing creativity, empirical research examining the relationship between such leadership and innovation remains scarce (Hsieh et al., 2022; Lee & Cassidy, 2007; Muenjohn & McMurray, 2017). This contribution is particularly noteworthy in the context of SMEs, where innovation is a key competitive advantage (Casals, 2011; Davis & Bendickson, 2021; Mbizi, 2013; Rhee & Stephens, 2020). Second, this study not only shifts attention toward design leadership but also delves into factors that foster such leadership, including WVE, and that support a culture of creativity and innovation in SMEs. Third, this study provides deeper insights into the mechanisms by which enhanced WVE contributes to workplace innovation, elucidating the interconnectedness between design leadership and WVE. By illuminating these interrelations, this study offers valuable implications for fostering innovation within SMEs and advances our understanding of the role of design leadership in driving SME creativity and competitiveness. Fourth, this study expands the validity of design leadership and confirms four different levels of workplace innovation. The findings offer invaluable practical recommendations for Asian SMEs entrepreneurs, deepening our understanding of how entrepreneurs’ values affect their leadership behaviors and their ventures’ innovativeness.

The next two sections of this paper discuss the relevant literature and develop our hypotheses, respectively. Then, the research method is explained, followed by the findings and discussions in light of previous research. The paper concludes with a summary of the major findings and outlines their implications for the SME literature.

Literature ReviewWorkplaces benefit from embedded innovation as it enhances skill development and, in turn, productivity. Rhee and Stephens (2020) argued that the effective use of innovation strategies helps develop a comprehensive innovation capacity and model that enhances firms’ competitive advantage and performance. Meanwhile, Pot (2011) proposed that embedding workplace innovation is impractical because managers tend to focus on short-term results, leading to a lack of resource allocation to support long-term workplace innovation. He believed that employers are not interested in changing their current balance of power with managers. Concerning SME resources, Colclough et al. (2019) asserted that there is no clear hypothesis regarding the influence of resource scarcity on SME innovation. Meanwhile, Exposito and Sanchis-Llopis (2018) suggested that the relationship between SMEs’ innovation choices and business performance should be analyzed using a multidimensional approach.

The recommendation for long-term investment in workplace innovation is echoed in the study conducted by Oeij et al. (2012). Because organizations tend to focus on short-term goals, it is often the case that they do not consider beneficial the adoption of a long-term vision. This implies that changes in workplace arrangements may contribute to lifelong learning for both firms and individuals. Meanwhile, Oeji et al. (2012) pointed out the role of workplace information technology in supporting employees and improving their skills, which may thereby lead to enhanced performance and productivity through task automation, also referred to as the “bundling of tasks.” Similarly, Khan et al. (2022) argued that the use of information technology in the workplace is an important factor that leads to improved innovation and performance, enabling employees to manage their innovative ideas. Nonetheless, Borghans and Ter Weel (2006) pointed out that information technology implementation more often results in specialist tasks if such technology is used to improve communication. This cited study also described that a lower division of labor tends to upgrade employee skills and improve productivity, thereby providing a broader purpose for information technology in the workplace innovation process.

Based on innovation research in the United States of America, a market with a grand application of information technologies, Gordon (2003) argued that information technology does not fulfill all innovation needs. Similarly, Black et al. (2004) underscored the overemphasis on the effect of information technology on productivity by comparing the United States of America context with that of Europe. These authors concluded that there is a degree of optimism about the effect of information technology in the United States of America's “New Economic” that began in the 1990s, and argued that other factors (e.g., profit sharing and wage level) also contribute to productivity growth. Høyrup (2010) described innovation as necessary to society, particularly to knowledge-based societies where research, including development and education, is critical for the economy. This cited author further observed that such economies value reflection, recognition, and teamwork, processes which are often embedded in organizations and economic cultures that possess the desire to develop skills through experience.

According to Vicere et al. (1998), long-term effectiveness is not developed by a strategic plan but rather by strategic intent, and the shape of leadership design and management is shifting. These ideas are supported by Dinh et al. (2014), who agreed that the field of leadership design has developed in recent years. In addition, Day (2000) asserted that although many articles address leadership theory, there is a lack of literature on leadership development. While noting the importance of defining the differences between developing leaders and developing leadership, as well as reaffirming these characteristics, Day et al. (2014) added that leadership development is a process that persists over time.

McCauley et al. (2006) investigated a large body of studies that reviewed constructive-developmental theory, which posits that the adult brain continues to develop cognitively, to find that no literature describes how training programs affect cognitive development. Another theory relevant for the current study is authentic leadership as modeled by Gardner et al. (2005), which emphasizes the importance of the relationship between managers and their followers. These cited researchers found that the shared ethical views within a company and the openness in a company's hierarchy build trust and support between leaders and followers, an idea that is contrary to the traditional view that emphasizes profits over people's work ethics. Although this theory is relatively new, several scholars have adopted it over the past decade (Avolio et al., 2018; Gardner et al., 2011; Gardner et al., 2021; Leroy et al., 2015).

The relationship between SME managers and employees can also significantly influence leadership dynamics within an organization. In owner-owned SMEs (i.e., the owner serves as the primary manager/leader), the relationship tends to be more direct and hands-on; meanwhile, family-owned SMEs may exhibit distinct leadership dynamics shaped by familial ties and traditions, and often involve a blend of familial authority and professional management practices (Erdem & Atsan, 2015). Regardless of the relationship type between managers and employees, fostering a workplace culture rooted in trust is imperative for SMEs to cultivate innovation.

Design leadership is considered as an emerging form of leadership (Hoozée & Bruggeman, 2010; Hsieh et al., 2022; Lee & Cassidy, 2007), and is defined as a leadership behavior that creates and sustains innovative design solutions (Turner & Topalian, 2002). As noted by Joziasse (2011), design leaders are skilled at balancing the exploration of innovative opportunities for the organization, and design leadership leads from vision creation to the operationalization of changes, innovations, and creative solutions.

According to Turner and Topalian (2002), the qualities of design leadership are displayed through a design leader's core responsibilities, including envisioning the future, manifesting strategic intent, and directing design investment. Joziasse (2011) also argued that design leaders tend to share three general qualities, as follows: (1) visualize the future to see what is changing and what opportunities may arise from change; (2) strategically think about core organizational competencies for securing market competitiveness; (3) skillfulness in leading others to develop, inspire, and maintain teams. Consequently, design leadership can be seen as an innovative form of leadership that stimulates communication and collaboration through motivation, as well as the clarification of ambitions and future directions for achieving long-term objectives. In light of all these descriptions, this study defines design leadership as leadership that creates and leads design thinking within an organization, that comprises qualities that influence the building of commitment, that integrates strategic design into the organization's vision, and that nurtures a design-oriented, innovative environment.

WVE is defined as a constellation of work-related values and attitudes (Miller et al., 2002), and is believed to improve the relationships between organizations and employees by increasing the latter's commitment (Chatzopoulou et al., 2022; Fu & Deshpande, 2014). The protestant work ethics was first proposed by Max Weber in 1905, who outlined its influence on American capitalism by describing work ethics as working hard for society and own happiness. These values hold in some form in today's modern world, albeit not in their entirety. They are viewed as an effective and productive enterprise where there needs to be quality of work value. The literature identifies many factors that contribute to these values, including culture, age, family business (Espíritu-Olmos & Sastre-Castillo, 2015), managerial spirit (Koonme et al., 2010), and the firm's overall ethical standpoint (Bird, 1988). Indeed, there is value in religious work ethics studies because they discuss the ideals and beliefs of religion, such as salvation and hard work fetching rewards for the devotee, which remain relevant even a century after Max Weber's propositions (Choi et al., 2021; Parboteeah et al., 2008). The literature agrees with this sentiment and asserts that religion and education contribute to strong work ethics (Schaltegger & Torgler, 2010). The potential reasoning for both religion and education being connected lies in the important role that education plays in religion and its focus on being protestant.

Becker and Woessmann (2009) are opposed to religion having such a considerable influence in the relationship between the two concepts, and suggest that it is potentially a façade that a higher level of education among workers leads to a higher income. While this contrasts with the findings of other researchers, they did not rule out the influence of religious ideology—and therefore of WVE—on economic growth. Van Hoorn and Maseland (2013) found support for the existence of the protestant work ethics in modern times, although they admitted that they were unable to determine with certainty that persons with strong work values were not drawn to the value of the protestant way of life.

Weber discussed the influence of religious mindsets on work ethics based on further analysis of how culture and diversity affects a society's work ethics (Becker & Woessmann, 2009). When investigating modern work ethics, Hugman (2012) believed that shared humanity and culture would contribute to the understanding of the value and ethics of work, and that some universal values and ethics can be identified using Maslow's hierarchy of needs (i.e., where the principles of needs and wants help shape value) as a model to reaffirm universality. A culture with a desire to innovate and be successful in that space will influence its economy to some degree (Hugman, 2012).

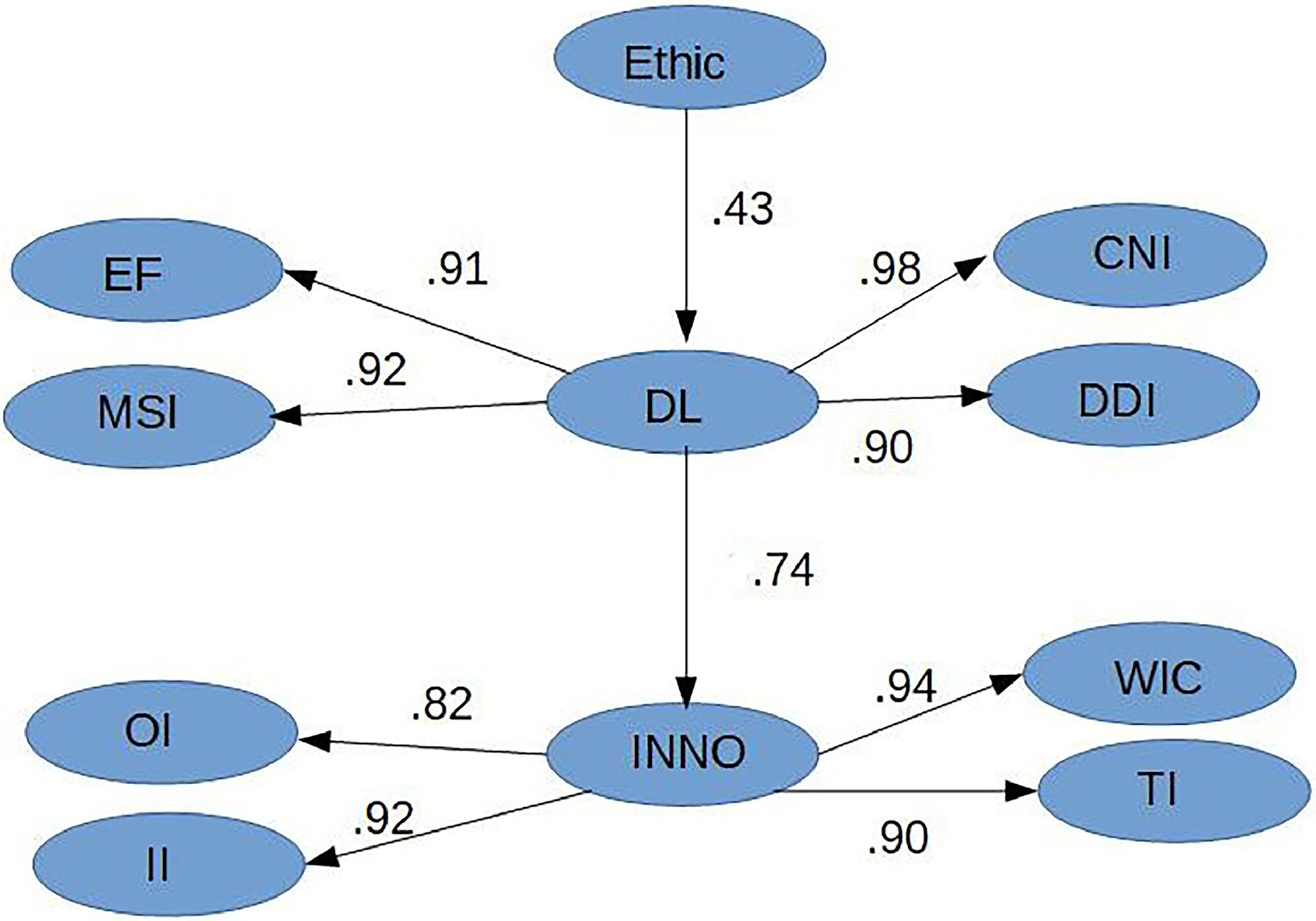

Research framework and hypothesesThe prior literature review section facilitated the development of the conceptual framework on which the five hypotheses outlined in this section are based. Fig. 1 illustrates the conceptual model of this study regarding the relationships between WVE, design leadership, and workplace innovation. It proposes that WVE correlates with design leadership, which then correlates positively with workplace innovation. The proposed relationships are explained in detail in Fig. 1 and are presented in Table 1.

Abbreviations used in Tables and Figs.

There are challenges to innovation in organizations when it relates to the pursuit of change. Pot and Koningsveld (2009) argued that there is an urgent need to develop a workforce with critical competencies. This growing need to stay up-to-date among workers is ever increasing, and organizations need to remain at the top of innovation changes because workplace innovation is a constant requirement in modern workplaces. Leaders may not always be equipped to handle changes well; thus, there is a need to plan and design how to lead change and filter the relevant workers that may support such change.

In the workplace, leader functionality is vital; Sternberg (2008) noted that the essential qualities leaders often desire and work to develop are wisdom, intelligence, creativity, and interpersonal skills. A leader needs creativity to generate ideas, intelligence and wisdom to decide whether an idea is worthwhile, and interpersonal skills for use in the workplace. While creativity varies across leaders, it is a common trait in successful leaders, and is considered necessary for leading companies toward innovation. Therefore, it is necessary to assess and act upon changing situations and projects, and creativity development and training is essential for leaders, not only for their own personal gains but also for the benefits it brings to their employees. Indeed, leadership in SMEs impacts innovation and organizational performance (Ofosu et al., 2023).

Leaders need to be accessible and open in their communication, as these characteristics enable inquiry and clarifications regarding workplace innovation and minimize resistance to change. In general, firm trust in the leadership team to adapt to, shape, and select work environments is beneficial for both employees and the organization. Sternberg (2008) observed that while leaders may not always make influential decisions, their poor decisions may negatively affect the business. Malik et al. (2024) found that leadership influences SMEs strategic agility in creating and managing a culture of trust, engagement, and, ultimately, innovation.

Innovation is crucial for improving firm efficiency and productivity (García‐Morales et al., 2008; de Jong & Vermeulen, 2006). Accordingly, understanding and assessing the innovation process within organizations is essential at the following four levels: organizational, climate, group/team, and individual levels (McMurray et al., 2023). Without proper assessment, development, and effective implementation of strategies encouraged from the top down, an organization can resist innovative changes. This suggests that the more leaders are involved with their employees and the more open is their communication, the more likely it is for workplace innovation to be successful. These descriptions lead to the following Hypotheses 1 and 2 (H1 and H2, respectively):

H1 Design leadership significantly correlates with workplace innovation.

H2 Design leadership significantly correlates with the four dimensions of workplace innovation.

Design leadership develops through the intent to develop a strong focus on business goals, not through a strategic plan (Vicere & Fulmer, 1998). Developing human capital to help drive the business into a secure and steady market position advances a human capital-focused company-wide culture. Therefore, the company's WVE must be enthusiastic and determined to attain a secure market position.

Becker and Woessmann (2009) proposed that human capital and WVE work in conjunction, and that the Protestant religion influenced literacy, resulting in better overall education levels and improved human capital. As the global economy becomes more competitive, stronger WVE along with specialized human capital will define organizations and set them apart. Society and culture also play roles in nurturing WVE. However, the company culture determines the effectiveness of the transposition of WVE. For a business to be strong in the market, its employees must have collective enthusiasm and organizational commitment, and the responsibility of maintaining such culture lies with leadership. Day (2000) identified that leadership is essential as it filters down to employees, and this identification supports the proposition by Schein (2010) that the leader is the carrier of culture.

If a manager and employee share the same ideals and values in life, they will have greater trust in one another (Gardner et al., 2011). This trust builds on openness and improved communication, which in turn positively influence businesses. Workplace culture can be influenced from the top down, as when employees trust their leaders, they will work harder, possibly owing to fewer differences with their leaders’ WVE. While this description may not address all situations in which leaders and workers improve human capital, it may account for a considerable portion of such improving effect, and the aforementioned situation may influence employees to absorb traits similar to those of the leader, including interpersonal skills (Stenberg, 2008).

H3 WVE significantly correlates with design leadership.

H4 Design leadership mediates the relationship between WVE and workplace innovation.

Workplace innovation is an organization-wide focus that requires the involvement of every employee, and having a leadership skilled and trained in managing human capital promotes the achievement of organizational goals and targets. Day (2000) wrote about the importance of management improving their training abilities to influence employees. Gaining such skills and applying them to build a stronger culture can instill organizational values among employees that align with those of the organization. Gardner et al. (2005) believed that shared work ethics between leaders and employees builds trust and support. This two-way relationship is beneficial for a company in meeting its vision and mission statements. While the traditional view of firms placed profits over people, recent years saw this view shift toward an increasing emphasis on people over profits (El Alkremi et al., 2018; Glavas & Goodwin, 2013).

As this is a modern approach to business management, training is required to educate and develop those who will lead related changes. Two major strategic plans must be incorporated into the organization's strategic model to ensure workplace innovation. First, there should be a strategic plan to improve the company's relationship with its employees, and raise human capital; second, there should be a plan to advance the skills of leadership to promote and act on this development. A focus on improved strategies can encourage specialist tasks (Black & Lynch, 2004), which an organization can in turn utilize to differentiate itself in its industry. As the number of smaller companies increases, innovation and specialization in the marketplace become paramount. These tasks, when created by and for employees, can reassure and bolster employee value and, subsequently, their innovation appetite and abilities.

As aforementioned, innovation is a goal achieved collectively by the whole organization. Pot and Koningveld (2009) found that workplace innovation can help improve the quality of employees’ work life and subsequently lead to improved organizational performance. Unfortunately, they were unable to determine the factors that undeniably led such innovation, which may include diversity, incremental innovation or radical innovation, technology push or market pull, and short-term or long-term perspectives. Since each organization is different, the effects of these factors vary on a case-by-case basis. As modern businesses must have human capital innovation at the forefront of their strategies, they must focus on innovation strategies to create a suitable culture and nurture it within the leadership team. Organizations must view the long-term benefits of developing and implementing action plans to advance workplace innovation. Hussain et al. (2023) identified in their SME leadership study that employees’ innovative work behavior had a moderating role in Islamic work ethics. These descriptions lead to Hypothesis 5 (H5).

H5 Design leadership mediates the relationship between WVE and the four dimensions of workplace innovation.

This study investigates the mediating effect of design leadership on the relationship between WVE and workplace innovation in Asian SMEs. Four countries, namely Japan, China, Thailand, and Vietnam, were selected as the target countries because of their different stages of economic development and their roles in advancing business innovation in Asia. In this study, a balance between these two criteria (i.e., economic development and business innovation) was essential. While Japan and China represent developed or newly developed countries and are more advanced in their innovation implementation, Thailand and Vietnam are considered developing countries and have less innovative practices (Dutta et al., 2019; Gao & Zhou, 2019; United Nations, 2020).

According to the literature, researchers must determine the unit of analysis to avoid unnecessary data collection and uphold the research's focus (Cavana et al., 2001). For this study, data were collected from SME management leaders (i.e., unit of analysis) in four countries. This study focused on SME management leaders because they are more likely to understand their own and their companies’ operations, and an appropriate sample size from this population would make the results more generalizable to broader scenarios, leading to a greater breadth of relevant data (Patton, 2002; Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2010). Simple random sampling, a subtype of probability sampling (Sekaran & Bougie, 2016), was used for recruitment. All SME management leaders who met the criteria had an equal chance of being selected.

In the literature, there are divergent opinions about sample size appropriateness. For instance, Roscoe (1975) recommended a sample size of 30–500 for multivariate analysis, whereas Hair et al. (2010) suggested that 100 or more samples were sufficient for statistical analysis. Tabachnick and Fidell (2019) recommended a minimum of 300 samples, whereas Krejcie and Morgan (1970) proposed a sample size of 384 to ensure good decision-making and to represent the entire population. It is also advisable to avoid using small sample sizes when conducting multivariate analyses as this may lead to problems and produce unstable results (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988; Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

An online survey was administered to full-time SME management leaders working in China, Japan, Thailand, and Vietnam. The questionnaires were distributed to 300 SMEs in Vietnam, 300 in Japan, 600 in China, and 600 in Thailand. In total, 1,316 questionnaires were returned. The questionnaire consisted of 18 items on leadership behaviors, 24 items on the four dimensions of workplace innovation, and 5 items on WVE from three separate scales, all of which were shown to be reliable in various previous studies and contexts.

Before data analysis, the dataset was filtered by removing any possible examples of speeding or straight linings (Zhang & Conrad, 2014), as some respondents provided identical scores for sets of 18 or 24 items. Data with missing values were also deleted, as were cases with scores greater than the possible range of answers to the questionnaire items. This data filtering process yielded 995 valid responses from 104 Vietnamese, 181 Japanese, 273 Chinese, and 437 Thai SME management leaders.

Data analysis was conducted using partial least squares because the data were non-normally distributed. Specifically, we observed a multivariate Mardia skewness value of 116697.5512 and a Mardia kurtosis value of 238.5361, demonstrating the unsuitability of the dataset for a covariance-based structural equation modeling, and its suitability for partial least squares analysis. In addition, the research objective was theory development and prediction to identify key “driver” constructs (Hair et al., 2011, 2012; Henseler et al., 2016), rendering partial least squares analysis more appropriate. The data conformed to the requirement that the number of cases in the sample should be more than 10 times the largest number of structural paths directed at the second- or first-order latent constructs (Hair et al., 2011).

The first- and second-order constructs were identified as reflective in nature because the direction of the relationship was from the constructs to the indicator items. A partial least squares-based analysis of the data was performed using the R analysis package (Sanchez, 2013).

ResultsRespondentsMost respondents (36.45%) were aged between 31–40 years, followed by those aged 41–50 years (23.5%) and those aged 25–30 years (20.06%). There were 52.92% male and 46.48% female respondents. More than half held a bachelor's degree (58%), whereas only 16.24% held a master's degree and 15.49% finished secondary education. Approximately 25% of the respondents worked in the retail industry, while approximately 21.5% and 19.7% worked in the manufacturing and service industries, respectively. Other industries, such as agriculture, construction, and education, comprise a small proportion of the population at rates lower than 10%. Approximately 30% of the population worked in small-sized enterprises with 5–20 employees.

AnalysisComparisons of key variables among four countriesAnalysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare scores between different countries. There were significant differences in scores regarding design leadership between participants from Thailand and China, Japan and China, and Japan and Vietnam at a significance level of 1%. The difference between participants from Thailand and Vietnam was significant at a significance level of 5%. However, there were no significant differences between Vietnam and China and between Japan and Thailand. The ANOVA findings provide a comprehensive understanding of the comparisons of scores for design leadership between participants from the four countries involved in the study (Table 2).

Analysis of variance – design leadership

Regarding workplace innovation, the ANOVA results showed similarities to those for design leadership, as there were significant differences in scores between participants from Thailand and China, Japan and China, Thailand and Vietnam, and Japan and Vietnam at the 1% level. Additionally, there was a non-significant negative score variance between Vietnam and China (Table 3).

Analysis of variance – workplace innovation

Regarding WVE, the ANOVA results were different from those of the two prior variables of interest. Specifically, there were non-significant differences between participants from Japan and China and from Thailand and Vietnam. However, the differences between participants from Vietnam and China and from Japan and Thailand were significant. Notably, the score variances between Japan and Vietnam and between Japan and Thailand were negative (Table 4).

Analysis of variance – work value ethic

The data were used to examine an outer model of the individual first-order measurement model constructs, and an inner model of the relationships between WVE and the second-order constructs of design leadership and workplace innovation. The tables and diagrams showing the outputs from these analyses use the following abbreviations:

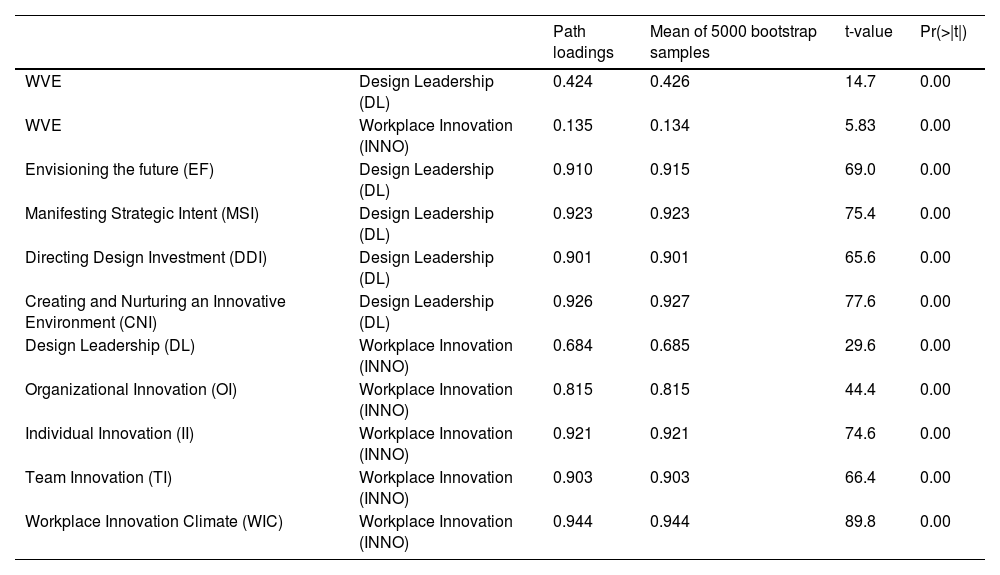

The loadings for each construct and their mean bootstrap values are listed in Table 5.

Construct loadings and mean bootstrap values

The results of the bootstrap sampling and analysis showcased great stability for the first-order construct loadings. The reliability values for the first- and second-order constructs are shown in Table 6, and confirmed the strength of their composition (as identified by only one major eigenvalue for each construct).

Reliability and eigenvalue values

The first eigenvalue for each construct was considerably larger than the second eigenvalue; this comparison of the first two eigenvalues can be considered as a measure of construct unidimensionality, which is confirmed when the first eigenvalue is much larger than the second eigenvalue (Sanchez, 2013). All Cronbach's α values were greater than 0.7 and hence considered to be satisfactory (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). The Cronbach's α is considered to represent the lower bound of reliability, while the Dillon-Goldstein ρ is proposed as a better measure of reliability (Henseler et al., 2016), and the latter was greater than 0.8 in all cases of this study. The analysis yielded a sound goodness of fit of 0.61 for the model.

After the various confirmations shown above, the relationships of WVE with the second-order constructs of design leadership and workplace innovation were explored (Table 7, Fig. 2).

Path loadings and path significance tests

Goodness of fit=0.6053

As described by Hair et al. (2012), the analysis results were checked using 5,000 bootstrap samples, and were found to exhibit scarcely any divergence from the obtained initial value.

Hypothesis testingRelationship between design leadership and workplace innovationThe analysis results are shown in Table 7 and Fig. 2. Design leadership that envisioned the future, manifested strategic intent, created and nurtured innovative environments, and directed design investment had a positive relationship with workplace innovation. Thus, H1 was fully supported.

Relationships of design leadership with the four dimensions of workplace innovation and with WVEThe results in Table 7 indicate that the relationships of design leadership with the dimensions of workplace innovation were significant, hence supporting H2. Concerning H3, it was supported by the findings, as WVE contributed significantly toward design leadership.

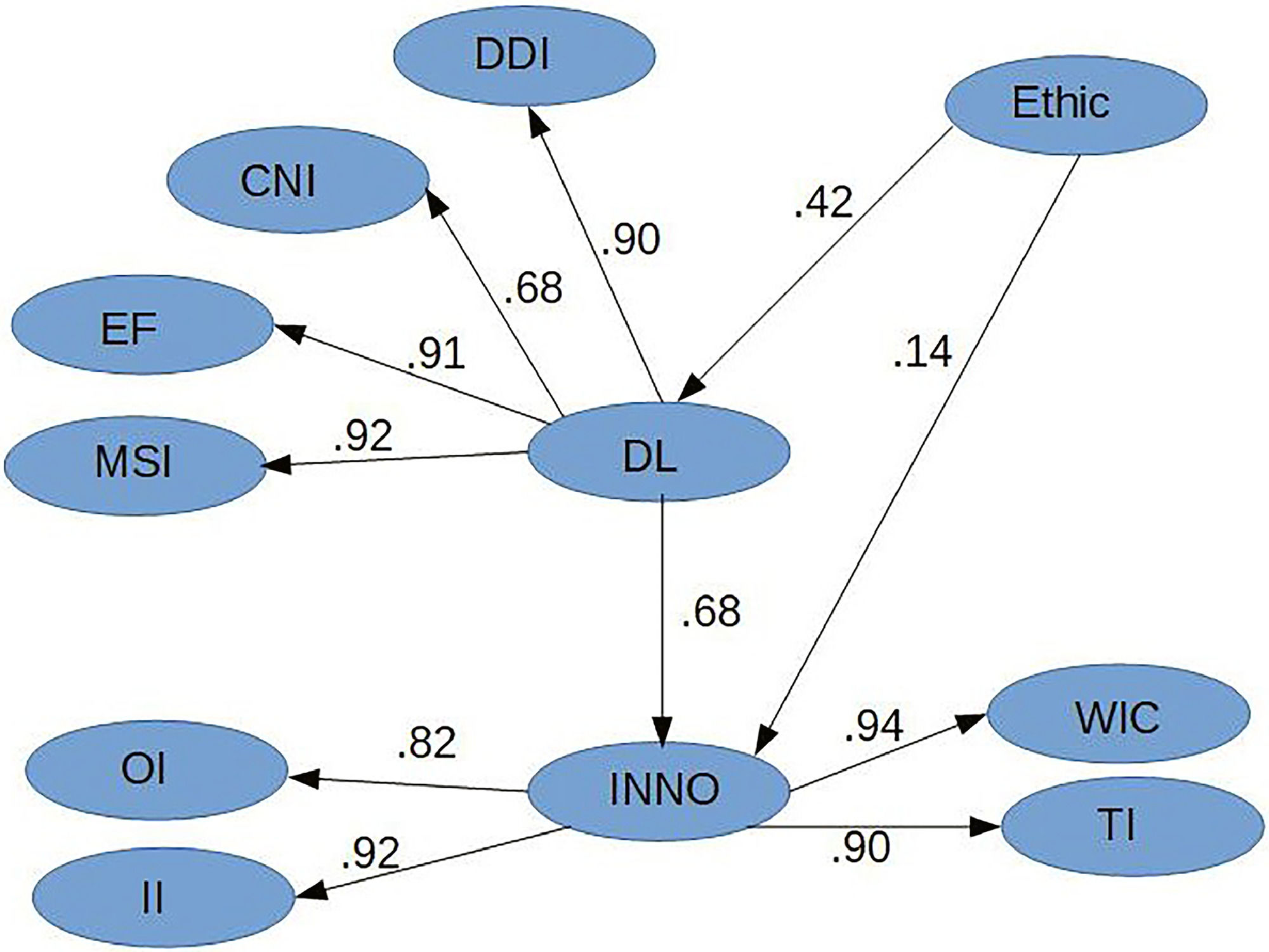

The Mediation of design leadership on the relationship between WVE and workplace innovationAn alternative set of relationships was examined to determine the possible mediation role of design leadership in the relationship between WVE and workplace innovation. Fig. 3 shows that WVE (represented by the Ethics variable) has a potential direct relationship with workplace innovation and an indirect relationship with such innovation through the mediation of design leadership. Furthermore, WVE was found to have a small positive relationship with workplace innovation that was significantly different from zero, indicating that design leadership acted as a partial mediator between WVE and workplace innovation. Thus, H4 was supported.

Table 8 presents the path loadings and significance tests for the mediated model. Both WVE and design leadership correlated significantly with workplace innovation.

Path loadings and significance tests for a model with design leadership as a mediator between wve and workplace innovation

Goodness of fit=0.6059

The path from WVE to workplace innovation was significant (t-test, 5.83; probability value, 0.00), while the paths from WVE to design leadership and from design leadership to workplace innovation showed an overall significant effect of 0.29. These results demonstrated the significant partial mediation effect and supported H5.

DiscussionThe results showed that design leadership significantly correlated with workplace innovation, thereby supporting the first two hypotheses (H1 and H2). The findings confirm that SMEs leaders who display behaviors associated with design leadership may associate with an increase in a firm's ability for innovation. This result is consistent with those in previous studies, indicating that successful innovation adoption is heavily related to leadership behavior. Becan et al. (2012), for instance, revealed that workshop-based interventions are facilitated by two essential mechanisms, namely innovative organizations with creative leadership and change-oriented staff attributes. Their study suggested that creative leaders supported innovative thinking and action, resulting in employees strengthening their own adaptive skills and incorporating innovative thinking into their work. In addition, Elenkov et al. (2005) confirmed that strategic leadership behavior associated positively with product, market, and administrative innovation. Ryan and Tipu (2013) revealed that active leadership has a significant positive effect on innovation propensity, while passive-avoidant leadership has a significant but weak positive effect on innovation propensity.

Additionally, our results indicate that WVE significantly correlates with design leadership (H3). Studies have partially confirmed this assumption by indicating that value ethics and effective leadership are positively correlated. For example, Hitt (1990) suggested a cause-and-effect relationship between ethical conduct and leadership. Klenke's (2005) study also supported that work values, including protestant work ethics and work involvement, are multi-level, multi-domain antecedents of leader behavior. We argue that shared individual and organizational values and ethics play essential roles in how leaders behave and lead organizations toward goal attainment.

The results also revealed that design leadership mediates the relationship between WVE and workplace innovation. We hence argue that leadership behaviors in Asian SMEs depend on one's values, and that both design leadership and WVE can significantly associate with an SME's ability to be innovative and, ultimately, competitive. Our argument is supported by Rujirawanich et al. (2011), who investigated how five factors associated with innovation interact with cultural value in Thai SMEs. Humphreys et al. (2005) conducted a six-year longitudinal study on innovation implementation in SMEs to reveal that SME innovation requires ongoing management effort and commitment.

Considerations should also be given to the context within which SMEs operate, as this can affect leadership quality and style. For example, Nwuke and Adeola (2023) found that SME leaders challenged by disruptions such as COVID-19, climate change, resource scarcity, and war became more strategic, future-oriented, and creative in seeking opportunities for innovation. This resonates with Malik et al.’s (2024) study on leadership styles in knowledge-intensive SMEs. In our study, we did not measure context variables, and thus could not conclude whether SME leadership differs depending on country economic development stage. Future studies should delve into these topics.

Importantly, we did not measure national culture, but do acknowledge that the consistent findings in our study might have been influenced by national culture values found across Japan, China, Thailand, and Vietnam, which made up the study sample. This point is acknowledged by Yu et al. (2019), who found in their comparative study of American and Taiwanese SMEs that national culture had an essential influence on family firm performance and autonomy, which is a key dimension of entrepreneurial orientation.

Theoretical contributionsThis study contributes to existing literature in several ways. First, it enriches the leadership and innovation literature by empirically examining how design leadership contributes to workplace innovation. As a relatively new and emerging concept of leadership, design leadership and its associations with innovation have been explored few times thus far. This study extends the existing literature by testing and validating that the display of design leadership associates with improved workplace innovation.

Second, the study expands knowledge regarding design leadership by providing evidence that WVE associate with bolstered design leadership behavior. It identifies shared individual and organizational values and ethics as important factors correlating with leadership behavior.

Third, it explains the mechanism by which design leadership mediates the relationship between WVE and workplace innovation, delivering empirical evidence on such mediation.

Practical implicationsThis study has two implications for practitioners. First, the findings suggest that design leadership implementation can be beneficial for SME innovation. Organizations aiming to enhance workplace innovation may set goals and implement strategies to help leaders and managers cultivate design leadership capabilities. They may, for instance, develop leadership training programs that provide opportunities for leaders and managers to diagnose their leadership styles, motivate them to integrate design thinking and design practice into their leadership behaviors, and cultivate visionary capabilities (Galli et al., 2017). Furthermore, the understanding that this study provides regarding the importance of design leadership and its association with workplace innovation is particularly key for the Asian SME context. In Asia, SMEs are fundamental for employment generation and innovation advancement, which are crucial for economic development (de Sousa Jabbour et al., 2020). This study suggests that SME leaders and policymakers in regions related to the countries explored in this study could put greater effort into the development of design leadership and innovation, as these actions may help improve SME performance in their economies.

Second, organizations that wish to develop design leadership and foster innovation should consider the relationships of these variables with WVE. Our findings identify WVE as a factor that relates to enhancements in managers’ design leadership in Asian SMEs. These organizations are thus suggested to create organizational cultures and practices that can foster shared work ethics such as commitment, dedication, ethical behavior, and trust (Hugman, 2012).

Limitations and future researchThis study had some limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, although the sample size was sufficient to examine the significant relationships between design leadership, WVE, and workplace innovation, the study was based on SMEs from only four Asian countries. Confining the study to the context of SMEs in Asian countries limited the generalizability of the findings. Future studies may use methods that enable the exploration of other types of organizations (e.g., large multinational enterprises and those beyond the four Asian countries) and check whether similar results emerge. Researchers are also invited to compare empirical results across different industries using industry-based analyses, which can afford more practical implications by drawing attention to how specific industry features influence the mediating role of design leadership on the relationship of WVE and workplace innovation.

Second, our data were collected at a single point in time, which precludes longitudinal examinations of the relationships under scrutiny. Future research could adopt a longitudinal approach to provide further insights into the causal relationships between these variables.

Third, we did not measure the influence of national culture on the relationships of interest. Yu et al. (2019) found that national culture differences significantly influenced firm performance and autonomy, which are key dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation. Academicians are thus welcome to conduct cross-national studies that consider the role of national culture in the mediated model encompassing design leadership, WVE, and workplace innovation.

Finally, this study examined the correlations between design leadership, WVE, and workplace innovation from the perspective of SME management. However, employees may have divergent perceptions of WVE and the efficacy of their managers’ leadership practices. Future research could collect data from multiple sources to provide deeper insights into the relationships among the variables of interest.

ConclusionThis study explored the direct and indirect relationships between design leadership, WVE and workplace innovation within Asian SMEs. The results indicated both direct and indirect relationships, albeit the indirect relationship was stronger, leading to the conclusion that design leadership mediates the relationship between WVE and workplace innovation.

These novel results extend the literature by underlining the complexity of the concept of design leadership and identifying its significant relationships with the dimensions of workplace innovation and WVE, which, to date, have been generally neglected in this field. The study's findings are relevant to both theory and practice and are specific to the Asian SME context.

CRediT authorship contribution statementNuttawuth Muenjohn: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Adela J McMurray: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Data curation, Conceptualization. Joseph Kim: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Leila Afshari: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.