The current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic poses an added risk in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), both because of their comorbidities and advanced age, and because they perform haemodialysis treatment in shared facilities. However, the impact has not been widely described, as studies so far are limited.1

During the pandemic, there has been controversy over whether the use of renin-angiotensin axis inhibitors increased the risk of infection or worsened the prognosis in patients with COVID-19.2 However, results from recent studies, such as the meta-analysis by Zhang et al., point to a possible protective role and have shown a lower risk of mortality in those treated with these drugs.3 However, the evidence regarding the use of these drugs in patients with CKD and COVID-19 respiratory infection is limited. The objective of the present study was to analyse whether the use of ACEIs or ARBs was associated with a higher risk of mortality in CKD patients hospitalized for COVID-19 respiratory infection.

For this, a prospective observational study was developed at the Ciudad Real University General Hospital, which included consecutive patients admitted for COVID-19 respiratory infection with a positive PCR for SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal swab in the months of March and April 2020, with the approval of the site's Clinical Research Ethics Committee. Of the total, 108 patients had CKD, defined as a glomerular filtration rate of less than 60 mL/min for at least 3 months before admission. The in-hospital course of these patients was analysed, with a median follow-up of 7 days (interquartile range 5–12 days).

The mean age was 80.0 ± 10.9 years and 52.8% were male. 63% of the patients were prescribed an ACEI or ARB prior to hospital admission. Compared to the rest, no significant differences were observed with respect to baseline characteristics, except for the prevalence of hypertension, which was higher in the ACEI or ARB group of patients.

50% (n = 54) of the CKD and COVID-19 patients died during admission. No significant differences were observed between the patients with prior prescription of ACEI or ARB and the rest in terms of mortality (48.5 vs. 52.5%; P = .69).

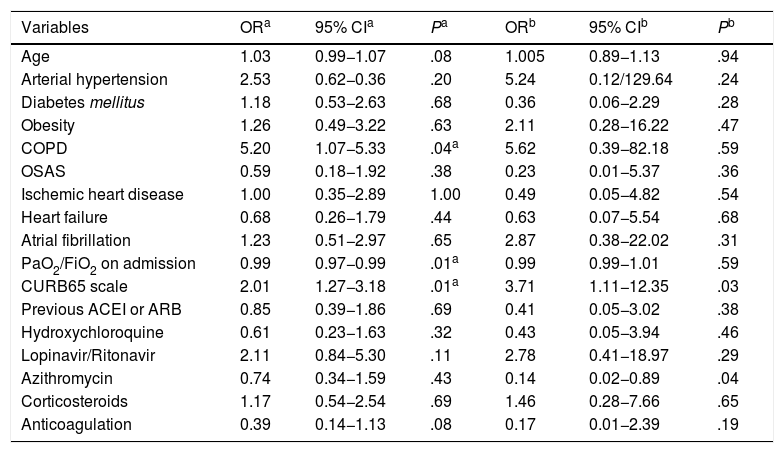

Prior treatment with ACEIs or ARBs showed no impact on the risk of in-hospital mortality either in the univariate analysis or after adjustment for those independent variables that showed statistical significance in the unadjusted analysis (Table 1).

Risk of in-hospital mortality.

| Variables | ORa | 95% CIa | Pa | ORb | 95% CIb | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.03 | 0.99−1.07 | .08 | 1.005 | 0.89−1.13 | .94 |

| Arterial hypertension | 2.53 | 0.62−0.36 | .20 | 5.24 | 0.12/129.64 | .24 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.18 | 0.53−2.63 | .68 | 0.36 | 0.06−2.29 | .28 |

| Obesity | 1.26 | 0.49−3.22 | .63 | 2.11 | 0.28−16.22 | .47 |

| COPD | 5.20 | 1.07−5.33 | .04a | 5.62 | 0.39−82.18 | .59 |

| OSAS | 0.59 | 0.18−1.92 | .38 | 0.23 | 0.01−5.37 | .36 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 1.00 | 0.35−2.89 | 1.00 | 0.49 | 0.05−4.82 | .54 |

| Heart failure | 0.68 | 0.26−1.79 | .44 | 0.63 | 0.07−5.54 | .68 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.23 | 0.51−2.97 | .65 | 2.87 | 0.38−22.02 | .31 |

| PaO2/FiO2 on admission | 0.99 | 0.97−0.99 | .01a | 0.99 | 0.99−1.01 | .59 |

| CURB65 scale | 2.01 | 1.27−3.18 | .01a | 3.71 | 1.11−12.35 | .03 |

| Previous ACEI or ARB | 0.85 | 0.39−1.86 | .69 | 0.41 | 0.05−3.02 | .38 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 0.61 | 0.23−1.63 | .32 | 0.43 | 0.05−3.94 | .46 |

| Lopinavir/Ritonavir | 2.11 | 0.84−5.30 | .11 | 2.78 | 0.41−18.97 | .29 |

| Azithromycin | 0.74 | 0.34−1.59 | .43 | 0.14 | 0.02−0.89 | .04 |

| Corticosteroids | 1.17 | 0.54−2.54 | .69 | 1.46 | 0.28−7.66 | .65 |

| Anticoagulation | 0.39 | 0.14−1.13 | .08 | 0.17 | 0.01−2.39 | .19 |

Data expressed as an absolute number.

ARB: angiotensin II receptor blocker; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; ACEI: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; OR: odds ratio; p: value of statistical significance; PaO2FiO2: ratio of partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood/fraction of inspired oxygen; OSAS: obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome.

Although the use of ACEIs or ARBs has been associated with overexpression of angiotensin-II converting enzyme (which has been postulated as an entry mechanism for SARS-CoV-2 infection) in the respiratory epithelium, several studies have not found an increased risk of hospital admission among patients previously prescribed these drugs.4

The results of the present study are consistent with the results of the most recent research regarding the effect of ACEIs or ARBs on the prognosis of patients with COVID-19. For example, Lopes et al. observed that the prognosis of the disease at 30 days was not modified among the patients who continued with these drugs.5

This is one of the first studies to analyse the effect of previous treatment with ACEIs or ARBs in patients with CKD and COVID-19. Although a neutral effect of this treatment on mortality in these patients has been demonstrated, its observational nature, together with the various limitations present (single-centre study, sample size, absence of a control group or short follow-up period) make its interpretation difficult, so randomised clinical trials are needed to provide evidence in this regard.

Please cite this article as: Mateo Gómez C, Martínez del Río J, Piqueras Flores J. Uso de IECA o ARA-II en pacientes con enfermedad renal crónica e infección respiratoria por SARS-CoV-2. Med Clin (Barc). 2021;157:e295–e296.