The appearance of a highly contagious disease forced the confinement of the population in almost all parts of the world, causing an increase in psychological problems, with pregnant women being a particularly vulnerable group to suffer negative consequences. The aim of this research was to check which confinement or psychological stress variables are related to the increase of anxious and depressive symptoms in pregnant women, as a consequence of the pandemic caused by the COVID-19.

Materials and methodsThe sample was composed of 131 pregnant women who experienced the confinement imposed by the Government of Spain on March 14, 2020. Sociodemographic, obstetric, confinement related and psychological variables were collected.

ResultsPerceived stress, pregnancy-specific stress, as well as insomnia are predictive variables in most anxious (obsessions and compulsions, anxiety and phobic anxiety) and depressive symptoms related to COVID-19.

ConclusionsIt is important to focus future psychological interventions in this population on stress control and sleep monitoring, since these variables influence the increase of anxiety and depression.

La aparición de una enfermedad altamente contagiosa obligó a confinar a la población en casi todo el mundo, ocasionando el aumento de problemática psicológica, siendo las mujeres embarazadas un grupo especialmente vulnerable a sufrir consecuencias negativas. El objetivo de esta investigación fue comprobar qué variables de confinamiento o estrés psicológico están relacionadas con el aumento de la sintomatología ansiosa y depresiva en mujeres embarazadas, como consecuencia de la pandemia ocasionada por la COVID-19.

Materiales y métodosLa muestra estuvo compuesta por 131 mujeres embarazadas que vivieron el confinamiento impuesto por el Gobierno de España el 14 de marzo de 2020. Se recogieron variables sociodemográficas, obstétricas, relacionadas con el confinamiento y variables psicológicas.

ResultadosEl estrés percibido, estrés específico del embarazo, así como el insomnio son variables predictoras en la mayoría de síntomas ansiosos (obsesiones y compulsiones, ansiedad y ansiedad fóbica) y depresivos relacionados con la COVID-19.

ConclusionesEs importante destinar futuras intervenciones psicológicas en esta población al control del estrés y monitorización del sueño, ya que estas variables influyen en el incremento de ansiedad y depresión.

The declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic in the world has led to a significant increase in anxiety symptoms in the population due to fear of infection as well as a worsening in the quality of sleep.1,2

Specific populations such as pregnant women may see this symptomatology increased, both due to the evolutionary stage in which they live and the growing concern due to the possible vertical transmission of the virus to their fetus.3

To date, there are no studies that have verified the psychological and lockdown variables that are related to anxiety and depressive symptoms derived from the lockdown situation. For this reason, the objective of this research was to verify which lockdown variables (type of home, loneliness, fear of infection, frequency of video calls or diet) and which psychological variables (pregnancy-specific stress, perceived stress, resilience, and insomnia) predict anxiety (obsessions and compulsions, anxiety, and phobic anxiety) and depression in pregnant women during the lockdown imposed in Spain due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Material and methodsParticipantsA total of 131 pregnant women participated in this study, with a mean age of 32.95 years (SD = 4.75) and a mean of 27.20 weeks of pregnancy (SD = 8.74).

All participants gave their voluntary informed consent, which was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2013) and the Directive on Good Clinical Practices (Directive 2005/28/EC) of the European Union. The protocol was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Granada (reference code 1580/CEIH/2020).

ToolsFirst, sociodemographic and obstetric variables were collected from the participants, such as age, week of gestation, educational level, etc.

Regarding the lockdown variables, the following variables were collected:

- -

Situation in relation to the pandemic: type of home (large sized house, medium sized house, small flat), feeling of loneliness and fear of infection.

- -

Habits and activities during lockdown: frequency with which calls and/or video calls have been made with loved ones and frequency with which a healthy diet has been maintained.

Second, to assess anxiety and depressive symptoms, the Symptom Checklist-90 Revised scale (SCL-90-R) was used.4

To complete the psychological evaluation, the Prenatal Distress Questionnaire (PDQ) was used3; to assess pregnancy-specific stress, the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14)5 was used; for general stress, the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC)6 and the Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS).7

ProcedureA panel of questions was developed using the Google Forms survey platform. The dissemination of the questionnaire began after the first month of lockdown in Spain and ended with the first phase of the de-escalation towards the new normality, in which people were allowed to go out for walks.

Analysis of dataFirst, a descriptive and frequency analysis of the main sociodemographic variables was carried out.

In order to find out what characteristics of lockdown, as well as what psychological variables influence anxiety and depressive symptoms, hierarchical linear regression analyses were performed, in which the dependent variables were the anxiety and depression symptom scores. The independent variables were included in the model through the following method: first step, the covariates age and gestation week (Block 1); second step, the lockdown variables (Block 2); finally, third step, the psychological scores (Block 3).

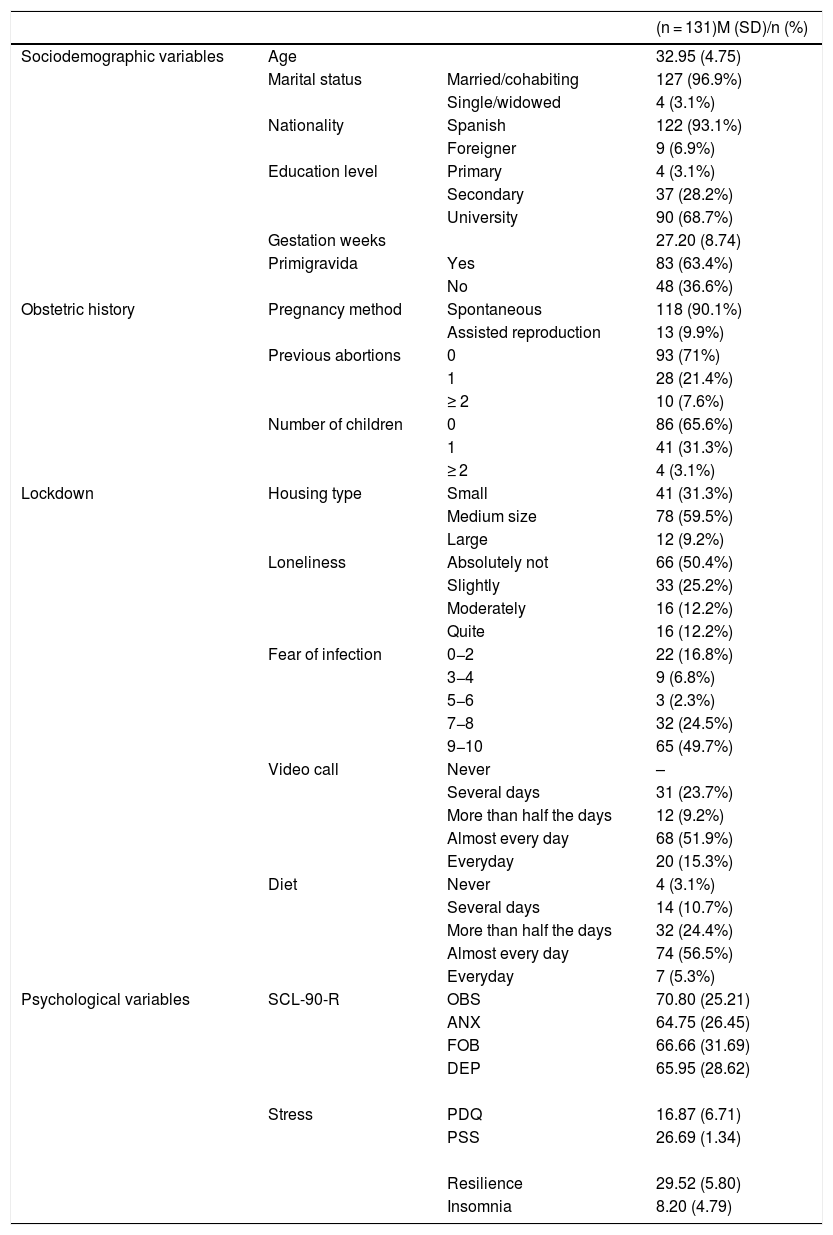

ResultsSample descriptionThe descriptive results can be seen in Table 1.

Sociodemographic variables, obstetric history, lockdown variables and psychological variables in the sample.

| (n = 131)M (SD)/n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic variables | Age | 32.95 (4.75) | |

| Marital status | Married/cohabiting | 127 (96.9%) | |

| Single/widowed | 4 (3.1%) | ||

| Nationality | Spanish | 122 (93.1%) | |

| Foreigner | 9 (6.9%) | ||

| Education level | Primary | 4 (3.1%) | |

| Secondary | 37 (28.2%) | ||

| University | 90 (68.7%) | ||

| Gestation weeks | 27.20 (8.74) | ||

| Primigravida | Yes | 83 (63.4%) | |

| No | 48 (36.6%) | ||

| Obstetric history | Pregnancy method | Spontaneous | 118 (90.1%) |

| Assisted reproduction | 13 (9.9%) | ||

| Previous abortions | 0 | 93 (71%) | |

| 1 | 28 (21.4%) | ||

| ≥ 2 | 10 (7.6%) | ||

| Number of children | 0 | 86 (65.6%) | |

| 1 | 41 (31.3%) | ||

| ≥ 2 | 4 (3.1%) | ||

| Lockdown | Housing type | Small | 41 (31.3%) |

| Medium size | 78 (59.5%) | ||

| Large | 12 (9.2%) | ||

| Loneliness | Absolutely not | 66 (50.4%) | |

| Slightly | 33 (25.2%) | ||

| Moderately | 16 (12.2%) | ||

| Quite | 16 (12.2%) | ||

| Fear of infection | 0−2 | 22 (16.8%) | |

| 3−4 | 9 (6.8%) | ||

| 5−6 | 3 (2.3%) | ||

| 7−8 | 32 (24.5%) | ||

| 9−10 | 65 (49.7%) | ||

| Video call | Never | – | |

| Several days | 31 (23.7%) | ||

| More than half the days | 12 (9.2%) | ||

| Almost every day | 68 (51.9%) | ||

| Everyday | 20 (15.3%) | ||

| Diet | Never | 4 (3.1%) | |

| Several days | 14 (10.7%) | ||

| More than half the days | 32 (24.4%) | ||

| Almost every day | 74 (56.5%) | ||

| Everyday | 7 (5.3%) | ||

| Psychological variables | SCL-90-R | OBS | 70.80 (25.21) |

| ANX | 64.75 (26.45) | ||

| FOB | 66.66 (31.69) | ||

| DEP | 65.95 (28.62) | ||

| Stress | PDQ | 16.87 (6.71) | |

| PSS | 26.69 (1.34) | ||

| Resilience | 29.52 (5.80) | ||

| Insomnia | 8.20 (4.79) |

ANX: anxiety; DEP: depression; PSS: Perceived Stress Scale; FOB: phobic anxiety; OBS: obsessions and compulsions; PDQ: Prenatal Distress Questionnaire; SCL-90-R: Symptom Checklist-90 Revised Scale.

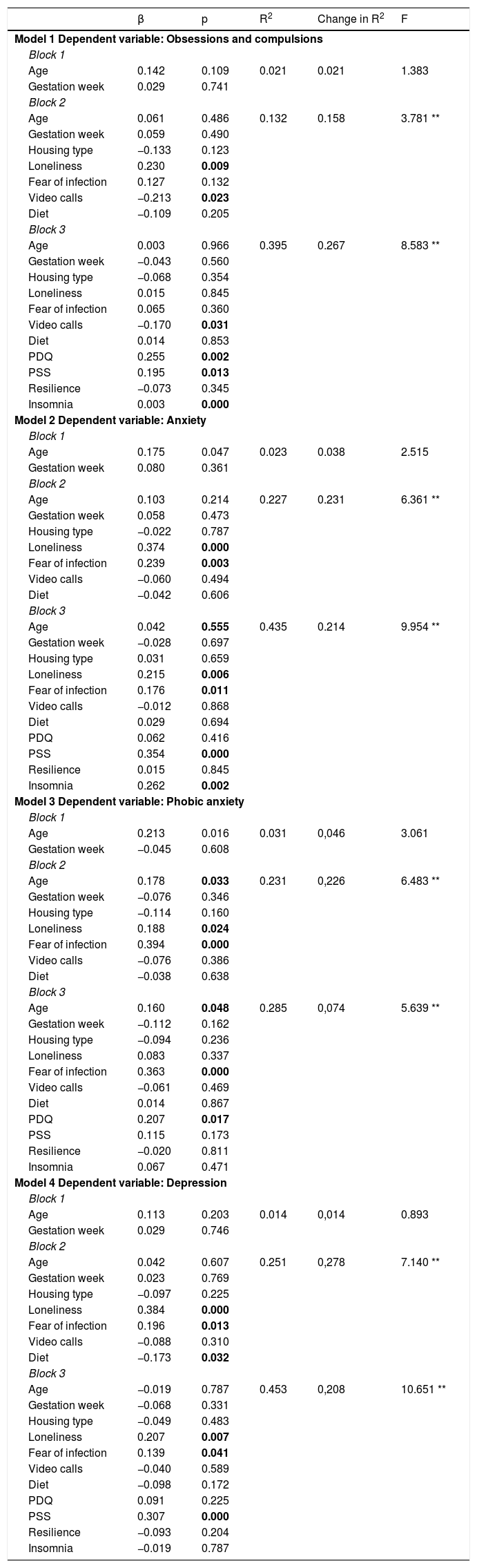

In the first model, in relation to the predictor variables of the scores obtained in obsessions and compulsions, in Block 3, this model showed an explained variance of up to 39%, with the predictor variables being the frequency of video calls (β = −0.170; p < 0.05), and PDQ (β = 0.255; p < 0.001), PSS (β = 0.195; p < 0.05) and insomnia (β = 0.003; p < 0.001) scores.

Model 2, whose dependent variable was anxiety, in Block 3, the model had an explained variance of 43%, with the predictor variables being loneliness (β = 0.215; p < 0.01), fear of infection (β = 0.176; p < 0.05), PSS (β = 0.354; p < 0.001) and insomnia (β = 0.262; p < 0.01) scores.

In model 3, Block 3, with 28% of the explained variance, showed the predictive power of age (β = 0.160; p < 0.05) and fear of infection (β = 0.363; p < 0.001), also including PDQ scores (β = 0.207; p < 0.05).

Finally, the fourth model has depression as a dependent variable. In Block 3, the explained variance reached 45%, with loneliness (β = 0.207; p < 0.01) and fear of infection (β = 0.139; p < 0.05) and PSS scores (β = 0.307; p < 0.001) as predictor variables.

The tolerance statistics (> 0.70) and VIF (< 10) were adequate, so the existence of collinearity between the independent variables is ruled out.

These data and the rest of the variables and blocks of each model can be consulted in Table 2.

Hierarchical linear regression analysis with anxiety and depressive symptoms as dependent variables.

| β | p | R2 | Change in R2 | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 Dependent variable: Obsessions and compulsions | |||||

| Block 1 | |||||

| Age | 0.142 | 0.109 | 0.021 | 0.021 | 1.383 |

| Gestation week | 0.029 | 0.741 | |||

| Block 2 | |||||

| Age | 0.061 | 0.486 | 0.132 | 0.158 | 3.781 ** |

| Gestation week | 0.059 | 0.490 | |||

| Housing type | −0.133 | 0.123 | |||

| Loneliness | 0.230 | 0.009 | |||

| Fear of infection | 0.127 | 0.132 | |||

| Video calls | −0.213 | 0.023 | |||

| Diet | −0.109 | 0.205 | |||

| Block 3 | |||||

| Age | 0.003 | 0.966 | 0.395 | 0.267 | 8.583 ** |

| Gestation week | −0.043 | 0.560 | |||

| Housing type | −0.068 | 0.354 | |||

| Loneliness | 0.015 | 0.845 | |||

| Fear of infection | 0.065 | 0.360 | |||

| Video calls | −0.170 | 0.031 | |||

| Diet | 0.014 | 0.853 | |||

| PDQ | 0.255 | 0.002 | |||

| PSS | 0.195 | 0.013 | |||

| Resilience | −0.073 | 0.345 | |||

| Insomnia | 0.003 | 0.000 | |||

| Model 2 Dependent variable: Anxiety | |||||

| Block 1 | |||||

| Age | 0.175 | 0.047 | 0.023 | 0.038 | 2.515 |

| Gestation week | 0.080 | 0.361 | |||

| Block 2 | |||||

| Age | 0.103 | 0.214 | 0.227 | 0.231 | 6.361 ** |

| Gestation week | 0.058 | 0.473 | |||

| Housing type | −0.022 | 0.787 | |||

| Loneliness | 0.374 | 0.000 | |||

| Fear of infection | 0.239 | 0.003 | |||

| Video calls | −0.060 | 0.494 | |||

| Diet | −0.042 | 0.606 | |||

| Block 3 | |||||

| Age | 0.042 | 0.555 | 0.435 | 0.214 | 9.954 ** |

| Gestation week | −0.028 | 0.697 | |||

| Housing type | 0.031 | 0.659 | |||

| Loneliness | 0.215 | 0.006 | |||

| Fear of infection | 0.176 | 0.011 | |||

| Video calls | −0.012 | 0.868 | |||

| Diet | 0.029 | 0.694 | |||

| PDQ | 0.062 | 0.416 | |||

| PSS | 0.354 | 0.000 | |||

| Resilience | 0.015 | 0.845 | |||

| Insomnia | 0.262 | 0.002 | |||

| Model 3 Dependent variable: Phobic anxiety | |||||

| Block 1 | |||||

| Age | 0.213 | 0.016 | 0.031 | 0,046 | 3.061 |

| Gestation week | −0.045 | 0.608 | |||

| Block 2 | |||||

| Age | 0.178 | 0.033 | 0.231 | 0,226 | 6.483 ** |

| Gestation week | −0.076 | 0.346 | |||

| Housing type | −0.114 | 0.160 | |||

| Loneliness | 0.188 | 0.024 | |||

| Fear of infection | 0.394 | 0.000 | |||

| Video calls | −0.076 | 0.386 | |||

| Diet | −0.038 | 0.638 | |||

| Block 3 | |||||

| Age | 0.160 | 0.048 | 0.285 | 0,074 | 5.639 ** |

| Gestation week | −0.112 | 0.162 | |||

| Housing type | −0.094 | 0.236 | |||

| Loneliness | 0.083 | 0.337 | |||

| Fear of infection | 0.363 | 0.000 | |||

| Video calls | −0.061 | 0.469 | |||

| Diet | 0.014 | 0.867 | |||

| PDQ | 0.207 | 0.017 | |||

| PSS | 0.115 | 0.173 | |||

| Resilience | −0.020 | 0.811 | |||

| Insomnia | 0.067 | 0.471 | |||

| Model 4 Dependent variable: Depression | |||||

| Block 1 | |||||

| Age | 0.113 | 0.203 | 0.014 | 0,014 | 0.893 |

| Gestation week | 0.029 | 0.746 | |||

| Block 2 | |||||

| Age | 0.042 | 0.607 | 0.251 | 0,278 | 7.140 ** |

| Gestation week | 0.023 | 0.769 | |||

| Housing type | −0.097 | 0.225 | |||

| Loneliness | 0.384 | 0.000 | |||

| Fear of infection | 0.196 | 0.013 | |||

| Video calls | −0.088 | 0.310 | |||

| Diet | −0.173 | 0.032 | |||

| Block 3 | |||||

| Age | −0.019 | 0.787 | 0.453 | 0,208 | 10.651 ** |

| Gestation week | −0.068 | 0.331 | |||

| Housing type | −0.049 | 0.483 | |||

| Loneliness | 0.207 | 0.007 | |||

| Fear of infection | 0.139 | 0.041 | |||

| Video calls | −0.040 | 0.589 | |||

| Diet | −0.098 | 0.172 | |||

| PDQ | 0.091 | 0.225 | |||

| PSS | 0.307 | 0.000 | |||

| Resilience | −0.093 | 0.204 | |||

| Insomnia | −0.019 | 0.787 | |||

PSS: Perceived Stress Scale; PDQ: Prenatal Distress Questionnaire.

In bold, the statistically significant values of the predictor variables (p < 0.05).

*Model significance p < 0.05.

The objective of this study was to verify which lockdown and psychological variables predicted anxiety and depressive symptoms caused by the pandemic in pregnant women.

Firstly, obsessions and compulsions in pregnant women increase according to the degree of pregnancy-specific stress, perceived stress and insomnia, and are alleviated by the frequency of video calls with relatives. The concerns that make up the specific stress, as well as the amount of care that these women require, are joined to the need to maintain extreme hygiene to avoid contagion, a factor that could explain the increase in obsessions and compulsions in this population.8

Secondly, in relation to anxiety, in addition to perceived stress and insomnia, it increases with feelings of loneliness and fear of infection. These results are in line with those found by Wang et al.,1 since the stress generated by the pandemic caused by COVID-19 has been associated with the fear of infection and its adverse consequences.1 In addition, the restriction of freedoms brought about by lockdown has increased feelings of loneliness in the population.

Phobic anxiety would increase with age, fear of infection and the pregnancy-specific stress. As the fear of infection and the number of concerns increases, the phobic symptoms would increase, which is consistent with the fears experienced by this population, both of becoming infected, and of the vertical transmission of the virus to the fetus.9

Finally, depressive symptoms in lockdown increase with loneliness, fear of infection and perceived stress. These results are explained by the close relationship that loneliness and stress have with depression.10

Therefore, taking into account all the predictive models, it seems that the variables that are most repeated in the worsening of anxiety and depressive symptoms are fear of infection, loneliness, and the stress experienced, above other variables typical of lockdown, such as the type of housing.

ConclusionsPregnancy is an extremely sensitive period and requires special attention, so these results have important implications since knowing the variables related to the state of anxiety and depression in this population would help us develop preventive measures for future outbreaks and lockdowns due to this disease or other similar ones.

FundingThis work has been financed by the Frontera Project "A-CTS-229-UGR18" of the Ministry of Economy, Knowledge, Business and University of the Junta de Andalucía, and co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER). In addition, Mr. José Antonio Puertas-González has an individual research grant (Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of Spain, FPU program, reference number 18/00617), as well as Dr. Borja Romero-González (Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness, FPI Program, reference number BES-2016-077619).

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank all the women who have participated in this study, as well as all the people who have battled against the virus. This study is part of Carolina Mariño-Narvaez's PhD/doctoral dissertation.

Please cite this article as: Romero-Gonzalez B, Puertas-Gonzalez JA, Mariño-Narvaez C, Peralta-Ramirez MI. Variables del confinamiento por COVID-19 predictoras de sintomatología ansiosa y depresiva en mujeres embarazadas. Med Clin (Barc). 2021;156:172–176.