Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) reactivation have been described in patients with invasive mechanical ventilation and recently in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) secondary to COVID-19 with higher rates of reactivation than were detected previously in critical care, and although the diagnosis of HSV-1 pneumonia is not easy, its presence is associate with an increase in morbidity and mortality. The objective of this study is to determinate if the identification of HSV-1 in lower airway of patients with ARDS secondary to COVID-19 have influence in clinical outcome and mortality.

MethodTwo hundred twenty-four admitted patients in intensive care unit (ICU) of Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Toledo diagnosed of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) were reviewed and were selected those with mechanical ventilation who had undergone (BAL). It was registered all results of HSV-1 PCR (negative and positive).

ResultsDuring the study period (November 28, 2020 to April 13, 2021) was admitted 224 patients in ICU diagnosed of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. Eighty-three patients of them had undergone BAL, with HSV-1 PCR positive result in 47 (56%), and negative result in 36 (43.4%). We performed pathological anatomy study in BAL samples on 26 of the total BAL realized. Typical cytopathic characteristics of HSV-1 were found in 13 samples (50%) and 11 of them (84.6%) have had HSV-1 PCR positive result. Thirty days mortality was significantly higher in the group of patients with HSV-1 PCR positive result (33.5% vs. 57.4%, p = 0.015). This difference was stronger in the group of patients with HSV-1 findings in the pathological anatomy study (30.8% vs. 69.2%, p = 0.047).

ConclusionOur results suggest that ARDS secondary to SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia is highly associated to HSV-1 reactivation and that the finding of HSV-1 in lower airway is associated with a worst prognostic and with significantly mortality increase. It is necessary to carry out more extensive studies to determinate if treatment with acyclovir can improve the prognosis of these patients.

Las reactivaciones del virus herpes simple (VHS) están descritas en los pacientes en ventilación mecánica invasiva y recientemente en el síndrome de distrés respiratorio agudo (SDRA) por COVID-19, con tasas más altas que las descritas previamente en pacientes críticos, y aunque el diagnóstico de neumonía por VHS es difícil, su presencia se asocia con aumento de la morbimortalidad. El objetivo de este estudio es determinar si la identificación de VHS en el tracto respiratorio inferior en pacientes en ventilación mecánica con SDRA por COVID-19 influye sobre la evolución clínica y la mortalidad.

MétodoSe revisaron 224 pacientes ingresados en el servicio de medicina intensiva del Complejo Hospitalario de Toledo con el diagnóstico de neumonía por SARS-CoV-2 y se seleccionaron los pacientes en ventilación mecánica a los que se les había realizado lavado broncoalveolar (LBA). Se registraron todos los resultados de la PCR, tanto si fue positiva como si fue negativa para VHS.

ResultadosDurante el periodo de estudio (del 28 de noviembre de 2020 hasta el 13 de abril de 2021) ingresaron 224 pacientes en la UCI con el diagnóstico de neumonía por SARS-CoV-2. De ellos, en 83 se realizó lavado broncoalveolar (LBA), siendo la PCR para VHS-1 positiva en 47 y negativa en 36 (56,6%). Realizamos estudio anatomopatológico en muestras de LBA a 26 pacientes del total de la muestra. Se encontraron características citopáticas típicas de infección por herpes en 13 (50%), de los cuales 11 (84,6%) tenían PCR positiva. La mortalidad a los 30 días fue significativamente mayor en el grupo de pacientes con PCR positiva (33,5% vs 57,4%, p = 0,015). Esta diferencia fue aún más marcada en el grupo con hallazgos anatomopatológicos compatibles con neumonía por VHS (30,8% versus 69,2%, p = 0,047).

ConclusiónNuestros resultados sugieren que el SDRA secundario a neumonía por SARS-CoV-2 se asocia a una alta reactivación del VHS y que su hallazgo en el tracto respiratorio inferior se asocia con un peor pronóstico y un aumento significativo de la mortalidad. Son necesarios estudios más amplios para determinar si el tratamiento con aciclovir puede mejorar el pronóstico de estos pacientes.

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) pneumonia is considered a rare entity affecting immune deficient patients such as transplant recipients, cancer patients and HIV-positive patients. Herpes simplex virus reactivation has been described in non-immunocompromised patients on prolonged mechanical ventilation and is associated with longer duration of mechanical ventilation and increased mortality.1,2

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) due to COVID-19 pneumonia is associated with immunosuppression secondary to lymphopenia and glucocorticoid therapy, with bacterial and fungal co-infections being common. HSV reactivations are described in patients with ARDS due to COVID-19, with higher rates than those described in critically ill patients,3 and although the diagnosis of HSV pneumonia is difficult, its presence is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.

Our aim is to assess the presence of HSV-1 pulmonary reactivations in patients with ARDS due to SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia and to evaluate their impact on prognosis.

Patients and methodRetrospective observational study conducted in the intensive care medicine unit of the Toledo Hospital Complex. All patients admitted from 28 November 2020 to 13 April 2021 with a diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia were reviewed. In our ICU, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed on all mechanically ventilated patients with a poor course, and this group of patients was the one evaluated. In addition to the usual microbiological studies, PCR for HSV was determined in the BAL, and an anatomical pathology examination was carried out in those patients in whom it was possible to do so. A positive anatomical pathology (AP) for HSV infection was defined as having cytopathological changes secondary to HSV infection itself (cytomegaly, multinucleated cells, nuclear pseudoinclusions, dyskeratinocytes and reactive cytological atypia and/or positive immunohistochemical staining to differentiate serotypes 1 and 2); if none of these alterations were found, AP was considered negative.4

Established diagnosis of HSV pneumonia was defined when PCR and AP were simultaneously positive.

As part of the management of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia, all patients were receiving glucocorticoids at usual doses (dexamethasone 6 mg/24 h), but none of those studied received chloroquine, anti-retrovirals or tocilizumab. If the patient had a poor progression and a positive PCR for HSV, treatment was initiated. They were treated with acyclovir (10 mg/kg/8 h iv).

Baseline patient characteristics, ICU admission and stay data and deaths at 30 days were assessed.

Statistical analysisQuantitative data are expressed as mean (standard deviation) and categorical data as number (percentage). The Chi squared test (χ2) was used for comparisons between categorical data and Fisher’s test if the expected frequencies were less than 5. Student’s t-test was used to compare quantitative data. Any value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

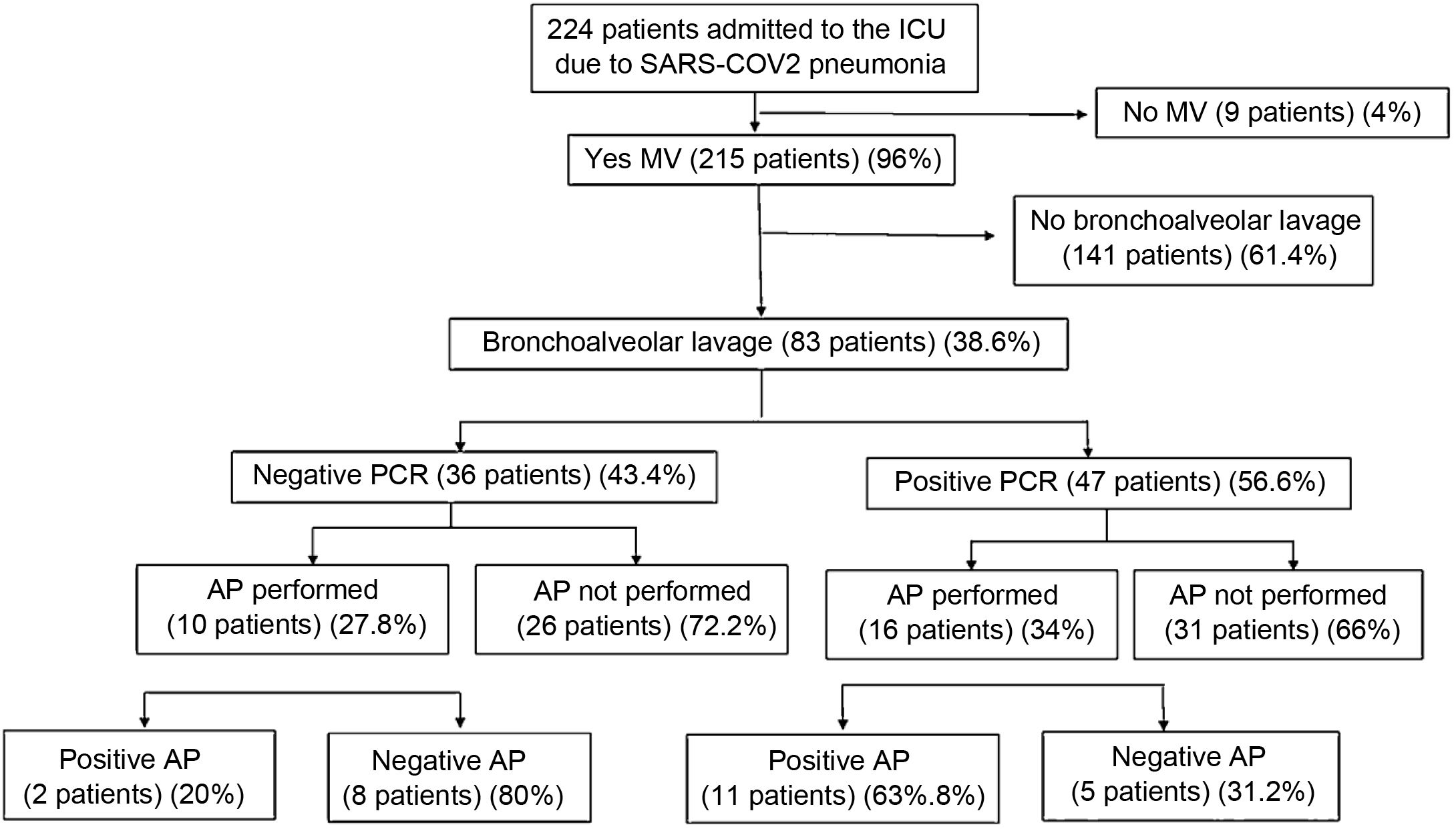

ResultsDuring the study period, 224 patients were admitted to the ICU with a diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia, performing BAL in 83 patients. HSV PCR was positive in 47 patients (56.6%). In all cases it was the serotype 1. A pathological study was carried out on BAL samples from 26 patients, finding typical characteristics of herpes infection in 13 (50%), of which 11 (84.6%) had positive PCR. Fig. 1 shows the flow chart of the results.

Table 1 shows the general characteristics for the whole sample and compares baseline and ICU progress data for PCR-positive and PCR-negative patients. Both groups showed no differences in personal history or inflammation data (white blood cells, D dimers, procalcitonin, C protein, ferritin, lymphocytes). If we compare the data according to PA with positive or negative data for HSV-1 infection and the data of patients with an established diagnosis for HSV pneumonia (positive PA and positive PCR) with negative patients (negative PA and negative PCR), no differences are found in any of the variables studied, except for mortality. Table 2 shows the 30 day mortality of the three groups compared (positive vs. negative PCR, anatomical pathology findings compatible with HSV pneumonia vs. no findings, and the combination of both vs. no findings).

Comparison between patients with and without positive PCR in bronchoalveolar lavage for herpes simplex virus in baseline and progress data.

| All patients | Negative PCR | Positive PCR | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 83) | (n = 36) (43.4%) | (n = 47) (56.6%) | ||

| Baseline data | ||||

| Males | 61 (730.6%) | 25 (69.4%) | 36 (76.6%) | 0.464 |

| Age | 60.98 (11.52) | 59.11 (13.2) | 62.40 (9.8) | 0.199 |

| BMI | 31.95 (8.2) | 31.7 (9.3) | 32.2 (7.3) | 0.784 |

| SOFA | 4 (0.86) | 4.3 (0.77) | 4.2 (0.61) | 0.574 |

| APACHE 2 | 10.16 (2.8) | 10.6 (3.1) | 9.8 (2.4) | 0.197 |

| UCI progress data | ||||

| Mechanical ventilation days | 26.32 (13.96) | 25.3 (16.2) | 27.1 (12.2) | 0.584 |

| ICU admission days | 28.04 (15.01) | 27.5 (17.3) | 28.4 (13.2) | 0.783 |

| Prone | 69 (83.13%) | 30 (83.3%) | 39 (83.0%) | 0.966 |

| Antibiotic | 66 (79.51%) | 24 (66.7%) | 42 (89.4%) | 0.011 |

| Coinfection | 40 (48.2%) | 15 (41.7%) | 25 (53.2%) | 0.298 |

| 30-day death | 38 (45.8%) | 11 (30.5%) | 27 (57.44%) | 0.015 |

APACHE: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; BMI: body mass index; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score; ICU: intensive care unit.

Quantitative data is shown as mean (standard deviation) and categorical data as number (percentage).

Deaths at 30 days according to the different comparison groups in relation to PCR and AP.

| Death at 30 days | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Negative PCR (n = 36) (43.4%) | 11 (30.5%) | |

| Positive PCR (n = 47) (56.6%) | 27 (57.44%) | 0.015 |

| Negative AP (n = 13) (50%) | 4 (30.8%) | |

| Positive AP (n = 13) (50%) | 9 (69.2%) | 0.047 |

| PCR and AP negative (n = 8) (42.1%) | 1 (12.5%) | |

| PCR and AP positive (n = 11) (57.9%) | 8 (72.7%) | 0.02 |

AP: anatomical pathology; PCR: polymerase chain reaction.

Categorical data is displayed as a number (percentage).

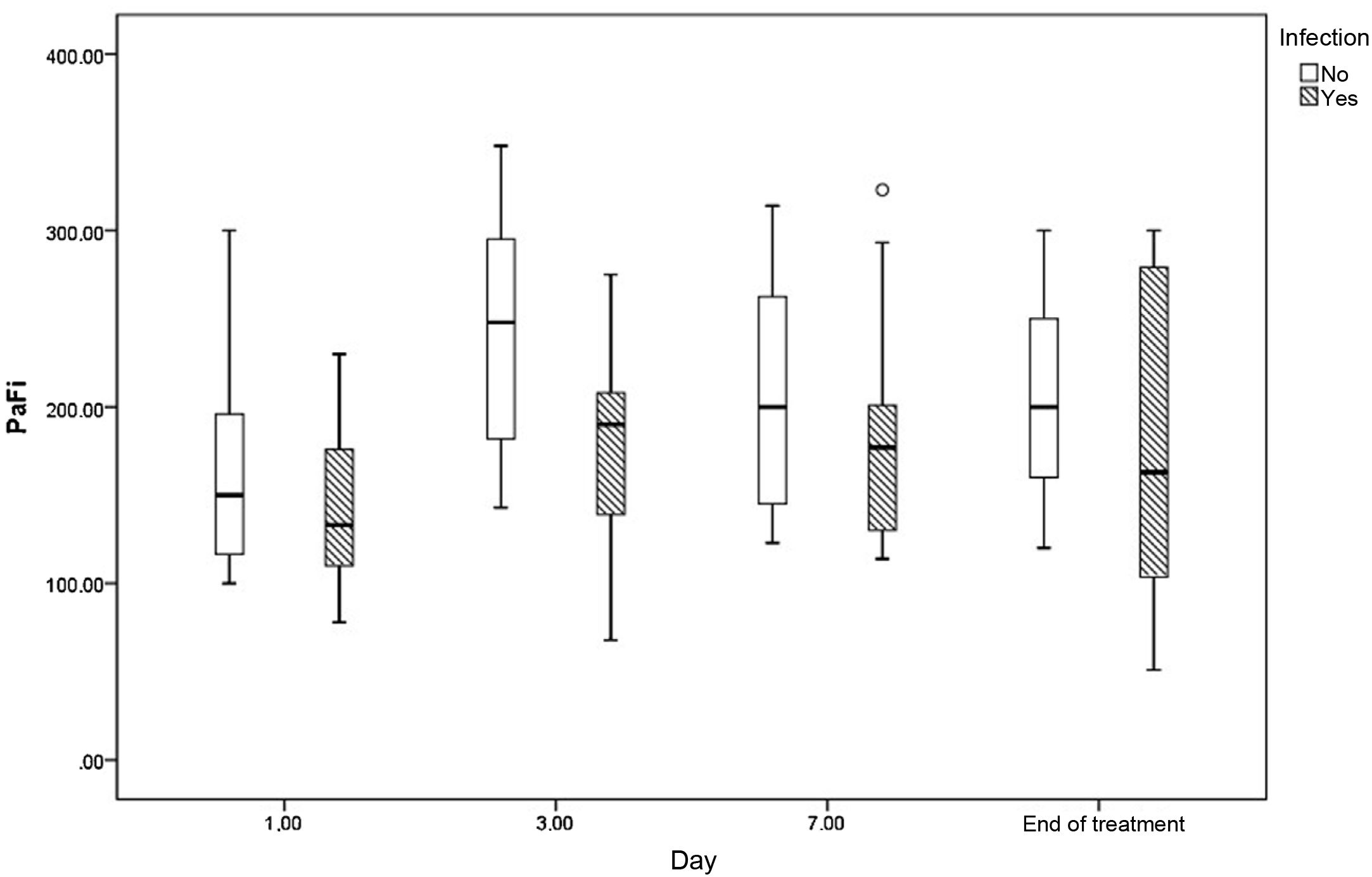

Fig. 2 shows the evolution of PaO2/FiO2 on days 1, 3, 7 and at the end of acyclovir treatment in those who were treated and in patients who did not have herpes virus infection.

DiscussionHSV pneumonia is considered a rare entity associated with states of immunosuppression. It is little thought of in immunocompetent patients on mechanical ventilation, although it has been described and is associated with a worse prognosis.1,2 HSV reactivation in the throat of patients ventilated for at least 5 days is rarely diagnosed and may be asymptomatic or manifest as herpetic ulceration of the lip or gingivostomatitis. The mechanism leading to reactivation is probably multifactorial, including immunoparalysis, microtrauma due to intubation, administration of immunosuppressants, etc.1,5 This reactivation may be the first step in ventilator-associated viral pneumonia.

The diagnosis of pulmonary herpes simplex infection is difficult and there is no consensus in critically ill patients. It is generally accepted as a diagnosis of certainty if there are anatomical pathology changes determined by BAL or biopsy. The characteristic features of HSV infection on biopsy are the presence of multinucleated cells with intranuclear ground-glass changes and Cowdry-like intranuclear inclusion bodies in the affected tissues. Detection of these histological features of HSV tissue infection is quite specific for true lower respiratory tract infections. Cytopathic changes in BAL such as cytomegaly, multinucleated cells, nuclear pseudoinclusions, dyskeratinocytes, and reactive cytological atypia and/or immunohistochemical staining are also considered diagnosis of certainty criteria.6,7 There are no defined criteria for the diagnosis of HSV pneumonia in the absence of anatomical pathology findings; patients are classified as proven HSV infection when the virus is present in bronchial secretions in combination with positive cytology, as probable HSV pneumonia only with positive micro-biology and no other pathogens, and as possible pneumonia if positive micro-biology is accompanied by other pathogens.8 Viral load is an important factor as a predictor of HSV pneumonia. HSV-1 PCR load >100,000 copies/ml in BAL specimens is associated with increased mortality in histologically proven HSV pneumonia.2

There are few anatomical pathology studies of lung samples in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Although it is also a viral pneumonia, the few published studies of BAL specimens do not show any specific cytomorphological features.9,10 In the few autopsies performed, vascular findings are characteristic of COVID-19, consisting of severe endothelial injury, generalised thrombosis with microangiopathy, alveolar capillary microthrombi and neoangiogenesis.11

In our series, of the 16 patients with positive PCR for HSV who underwent a pathological examination, the diagnosis of HSV pneumonia was confirmed in 11 (68.8%). Without cytology samples, we cannot make an established diagnosis in the remaining cases, although we can make a diagnosis of probable infection according to the diagnostic criteria. These results suggest that HSV reactivations in patients with ARDS due to COVID-19 are more common than in previous studies conducted in patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation for other causes. We attribute this increase to immunosuppression due to lymphopenia and treatment with glucocorticoids. Initially, the team of physicians wondered whether the positive PCR results could be indicative of viral replication without further clinical relevance or superinfection, without knowing for sure whether this finding could be involved in the clinical deterioration of our patients. Given the severity of the clinical symptoms and based on previously published work in critically ill patients and in patients with COVID,3 we decided to initiate targeted treatment and observe the clinical course.

With regard to the outcome of our patients, we observed that mortality was significantly higher in the PCR-positive group. HSV detection in the lower respiratory tract in hospitalized and mechanically ventilated patients has been associated with increased morbidity and hospital stay,12–14 as well as mortality.15,16 Treatment with acyclovir is controversial. One study showed that in 29 ICU patients with a positive culture for HSV, acyclovir significantly decreased hospital mortality to 28%, compared to 48% in untreated patients (p = 0.003).17 Schuierer et al.16 published that acyclovir significantly improved median ICU survival, was associated with lower risk of death in patients with high viral load and improved oxygenation as measured by PaO2/FiO2 on days 3 and 7 of treatment.

Herpes infection in our patients was associated with a significant increase in mortality in all compared groups, with mortality being much more significant in the group with AP-established diagnosis (72.7% versus 12.5%, p = 0.02). Mortality reported in other series is higher than 70%, and even close to 100%.18–20 Like all our positive patients, they received acyclovir, and although we found that treatment improved the oxygenation curve on days 3 and 7 (Fig. 2), we cannot draw conclusive results on the impact this may have had on mortality, as we have no untreated control group.

The limitations of this study include the fact that it was conducted in a single centre, that it is retrospective, with a low number of the sample with a pathological examination, which prevents drawing generalised conclusions, and with the lack of a control group to assess the impact that treatment with acyclovir may have had. The small number of patients prevented us from carrying out a multivariate study, which would have contributed to more conclusive results.

Nevertheless, the present study is to date, and to the best of our knowledge, the only one to present conclusive pathological specimens with a diagnosis of HSV pneumonia in patients with ARDS due to COVID-19. We were able to determine that more than half of the patients with a poor clinical course who were screened for opportunistic infections met criteria for HSV reactivation, and that 50% of the cytological studies performed showed diagnostic criteria for infection. The fact that it is a retrospective study means that we know what is common practice in our daily clinical practice and allowed us to confirm the impact of positive PCR for HSV on 30 day mortality in these patients.

56.6% of the cases studied for HSV had positive PCR in the BAL specimens. Our results suggest that the association of HSV pneumonia in patients with ARDS due to COVID 19 is common and is associated with a worse vital prognosis. Choosing those with a poor course for BAL probably resulted in a higher prevalence of HSV, limiting giving a more comprehensive overview of the infection.

In conclusion, although HSV bronchopneumonia is considered a rare entity, our results suggest that ARDS due to SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia is associated with high HSV reactivation, and that its finding in the lower respiratory tract is associated with a worse prognosis and a significant increase in mortality. We believe that a patient with COVID-19 pneumonia on mechanical ventilation presenting clinical deterioration with suspected superinfection should undergo BAL for opportunistic microorganisms, including PCR and cytology for HSV. We think it is reasonable to consider the potential benefit of antiviral treatment despite the current controversy over the indication of acyclovir in light of these findings.15,16,21 It is true that with our data we cannot determine whether antiviral treatment could have improved the survival of our patients, but we believe that given the seriousness of the situation and the unquestionable impact of a positive PCR for HSV on mortality, treatment with acyclovir would be justified, in the absence of more conclusive studies.

Ethical considerationsThis study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Toledo Hospital Complex.

FundingThis study has not received any funding.

Conflict of interestsNo author has any conflict of interest nor is there any conflict with any of the materials, drugs or devices of any entity used in the study.