To determine the prevalence of hypotension and associated factors in hypertensive patients treated in the Primary Care setting.

Materials and methodsA cross-sectional, descriptive, and multicentre study was conducted with a total of 2635 general practitioners consecutively including 12,961 hypertensive patients treated in a Primary Care setting in Spain. An analysis was performed on the variables of age, gender, weight, height, body mass index, waist circumference, cardiovascular risk factors (diabetes, dyslipidaemia, smoking, obesity, sedentary lifestyle), fasting plasma glucose, complete lipid profile, as well as the presence of target organ damage (left ventricular hypertrophy, microalbuminuria, carotid atherosclerosis) and associated clinical conditions. Hypotension was defined as a systolic blood pressure less than 110mmHg or a diastolic blood pressure less than 70mmHg. A multivariate analysis was performed to determine the variables associated with the presence of hypotension.

ResultsThe mean age was 66.2 years, and 51.7% of patients were women. The mean time of onset of hypertension was 9.1 years. A total of 13.1% of patients (95% confidence interval 12.4–13.6%) had hypotension, 95% of whom had low diastolic blood pressure. The prevalence of hypotension was higher in elderly patients (25.7%) and in those individuals with coronary heart disease (22.6%). The variables associated with the presence of hypotension included a history of cardiovascular disease, being treated with at least 3 antihypertensive drugs, diabetes, and age.

ConclusionsOne out of 4–5 elderly patients, or those with cardiovascular disease, had hypotension. General practitioners should identify these patients in order to determine the causes and adjust treatment to avoid complications.

Determinar la prevalencia de hipotensión y los factores asociados en pacientes hipertensos tratados en atención primaria.

Material y métodosEstudio transversal, descriptivo y multicéntrico; 2.635 médicos generales incluyeron consecutivamente a 12.961 pacientes hipertensos tratados y atendidos en atención primaria en España. Fueron analizados: edad, sexo, peso, altura, índice de masa corporal, perímetro de cintura, factores de riesgo cardiovascular (diabetes, dislipidemia, tabaquismo, obesidad, sedentarismo), glucemia en ayunas, perfil de lípidos, así como la presencia de daño en órgano diana (hipertrofia ventricular, microalbuminuria, aterosclerosis carotídea) y enfermedades clínicas asociadas. La hipotensión se definió como presión arterial sistólica inferior a 110mmHg o presión arterial diastólica inferior a 70mmHg. Se realizó un análisis multivariante para determinar las variables asociadas a la presencia de hipotensión.

ResultadosLa edad media fue de 66,2 años, un 51,7% de los pacientes eran mujeres. La antigüedad de la hipertensión fue de 9,1 años. Un 13,1% de los pacientes (intervalo de confianza del 95%: 12,4-13,6%) tenían hipotensión, de los cuales el 95% era presión arterial diastólica baja. La prevalencia de hipotensión fue mayor en pacientes de edad avanzada (25,7%) y en individuos con enfermedad coronaria (22,6%). Las variables asociadas con la presencia de hipotensión incluyeron los antecedentes de enfermedad cardiovascular, pacientes tratados con al menos 3 fármacos antihipertensivos, diabetes y edad.

ConclusionesUno de cada 4-5 pacientes de edad avanzada o con enfermedad cardiovascular tenía hipotensión. Los médicos generales deben identificar a estos pacientes para determinar las causas y ajustar el tratamiento para evitar complicaciones.

There is a direct relationship between increased blood pressure (BP) levels and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, without any evidence of a threshold down to at least 115/75mmHg.1 On the other hand, the reduction of BP with antihypertensive treatment in hypertensive population has been shown to decrease cardiovascular events by 30–50%, mainly in those patients at higher risk.2

Therefore, achieving BP targets is mandatory in patients with hypertension. However, there are some relevant differences regarding the recommended BP goals between international clinical guidelines. Thus, whereas 2007 European Society of Hypertension guidelines suggested “the lower the better”, particularly in patients at higher risk,3 in 2009 the same Society considered that due to the risk of hypotension, a BP target in the range of 130–139/80–89mmHg should be recommended.4 In 2013 the European guidelines, in line with Joint National Committee (JNC)-8, recommend a BP target of less than 140/90mmHg for the overall hypertensive population,5,6 and the current European guidelines of 2018 recommend a BP target of less than 130/80mmHg (but not <120/70mmHg) for the hypertensive population in <65 years and less than 140/80mmHg (but not <130/70mmHg) in older people (aged ≥65 years).7 The last American guide of 2018 recommend a BP target of less than 130/80mmHg for all patients.8

However, some studies, such as the meta-analysis of Bangalore et al.9 (15 clinical trials with 66,504 patients) suggest that in patients with coronary artery disease, a more strict BP target (less than 130mmHg) could be beneficial, but with a higher risk of hypotension.10 In the SPRINT trial,11 a more strict systolic BP goal (<120 vs <140mmHg) was associated with a 30% reduction in the risk of death and cardiovascular disease. However, the risk of severe hypotension and syncope was higher in those patients assigned to a stricter systolic BP target. On the other hand, different studies have shown that excessive BP reductions could be harmful in some patients.12–14

At this moment, the possible existence of a J-curve remains a topic of discussion. The J-curve implies that both high and excessively low levels of BP with antihypertensive treatment are associated with an increased cardiovascular risk. Thus, it seems that there is a lowest value of BP (nadir), which represents a point at which BP is too low to maintain an adequate perfusion of vital organs. This is particularly important regarding diastolic BP and in patients with coronary artery disease.15,16 Although it has not been clearly established, different studies have shown that BP levels below 110/70mmHg could increase cardiovascular risk.17,18

By contrast, other studies have suggested that the J-curve could be different according to the type of organ, and consequently, the optimal BP to achieve for each organ.20 With regard to the prevention of stroke, TNT,16 ONTARGET21,22 and ACCORD23 trials did not find a J-curve. Moreover, other studies have questioned the existence of the J-curve.24,25

Achieving BP goals in hypertensive population without increasing the risk of side effects related with antihypertensive treatment should be one of the main objectives of general practitioners.5–7

Hypotension related with antihypertensive treatment has not been clearly defined. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have specifically analyzed the prevalence of hypotension in hypertensive treated patients. The main objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of hypotension in hypertensive treated patients and the factors associated with its development.

Materials and methodsDesign of the studyPRESCAP (PRESión arterial en Centros de Atención Primaria) was a multicenter and cross-sectional study aimed to assess the BP control rates and clinical profile of treated hypertensive patients in primary care setting in Spain. Clinical characteristics of the study population, the methodology and the definition of variables have been previously described.26 In this study, the prevalence of hypotension of patients included in PRESCAP study was analyzed.

A total of 2635 general practitioners consecutively included up to 5 patients that met the inclusion criteria: subjects of both sexes; ≥18 years old; with an established diagnosis of hypertension and treated with antihypertensive therapy during at least 3 months previous to the inclusion. Patients with a recent diagnosis of hypertension (<6 months) or those undergoing treatment for <3 months of the recruitment, were excluded from the study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Clinic of Barcelona and every recruited patient gave a written informed consent before inclusion.

Variables of the studyThe variables analyzed in this study were: age (years), sex, weight (kg), height (cm), body mass index (kg/m2), waist circumference (cm), cardiovascular risk factors (diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, smoking, obesity and sedentary life style), serum fasting glucose, total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, left ventricular hypertrophy, carotid wall thickening (intima-media thickness >0.9mm) or plaque, microalbuminuria and associated clinical conditions (ischemic heart disease, stroke and chronic kidney disease). These data were collected from the clinical history of every patient. Biochemical data were recorded when blood tests were available within 6 months prior to inclusion. Renal insufficiency was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate <60ml/min (CKD-EPI).

BP readings were taken according to current recommendations, with the patients in a seated position and their backs supported, after a 5min rest, using calibrated aneroid or mercury sphygmomanometers or validated automatic devices, depending on the availability. The patients were advised to quit smoking or drinking coffee within 30min of BP assessment. The visit BP was the average of two separate readings taken by the examining physician, and a third measure was obtained when a difference of ≥5mmHg between the two measurements was detected. Hypotension was defined as a systolic BP <110mmHg or a diastolic BP <70mmHg (based on previous studies17,18 that suggest that below these values the patients cardiovascular risk may be increased), and adequate BP control was defined as BP <140/90mmHg. As a result, those patients with a systolic BP 110–139mmHg and a diastolic BP 70–89mmHg were considered as hypertensives with a good BP control and those patients with a systolic BP ≥140mmHg or a diastolic BP ≥90mmHg as hypertensives with poor BP control. The patients were asymptomatic, they came to the office to measure their BP in a routine way.

Statistical analysisFor the descriptive analysis, quantitative variables were described with measures of central tendency and dispersion (mean and standard deviation) and qualitative variables were described as absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies. The presence of normal distribution was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. In the bivariate analysis to compare 2 means, parametric (Student t test) or nonparametric (Mann–Whitney U test) statistical tests were performed based on the sample distribution. To compare percentages, the chi-square test or Fisher test was used, according to the sample size.

To assess factors associated with the presence of hypotension, a logistic regression analysis was performed using those variables that reached statistical significance in the bivariate analysis. Age, obesity, diabetes, chronic renal disease, sedentary life style, history of cardiovascular disease and polymedication were included as potential predictive factors in the analysis.

The data design was subjected to internal consistency rules and ranges to control for inconsistencies/inaccuracies in the collection and tabulation of data. Statistical significance was set at a p-value <0.05. The statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistics package, version 20.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

ResultsStudy population and prevalence of hypotensionA total of 13,420 patients were included in the study. However, 459 (3.4%) patients were excluded from the study because of not meeting the inclusion criteria and/or clinical records were incomplete and/or inconsistent. As a result, 12,961 patients were finally analyzed (mean age 66.2 years; 51.7% women; mean time of evolution of hypertension 9.1±6.7 years).

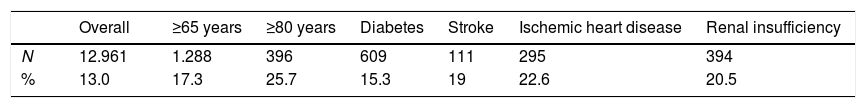

The prevalence of hypotension was 13% (95% CI 12.4–13.6%); 50.2% (95% CI 49.4–51.0%) of the study population had a good BP control; and 36.7% (95% CI 35.9–37.5%) of patients had a poor BP control. The prevalence of hypotension was similar between men and women (13.1% vs 13%, respectively). From those patients with hypotension, 12.4% of patients had low systolic BP, 95% low diastolic BP and 7.4% systolic BP and diastolic BP. From those patients with a systolic BP ≥140mmHg, 2.1% of patients had low diastolic BP. The prevalence of hypotension according to different clinical characteristics is shown in Table 1. The prevalence of hypotension increased with age and with the presence of cardiovascular disease. The prevalence of hypotension was 7.1%, 12.1% and 10.7% in patients <65 years (N=382), patients without diabetes (N=1076) and patients without cardiovascular disease, respectively.

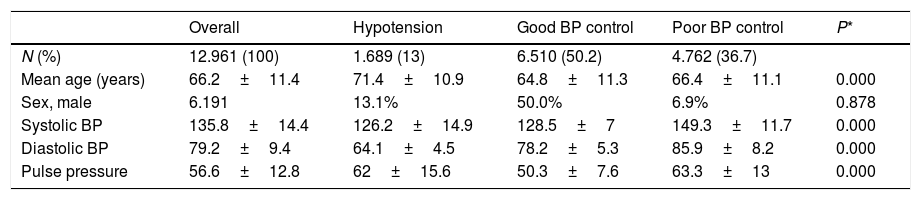

Clinical characteristics of the study populationMean values of systolic BP, diastolic BP and pulse pressure are described in Table 2 and the clinical characteristics of the study population according to the presence of hypotension, good BP control and poor BP control in Table 3. Mean age of patients with hypotension was 71.4±10.9 years and 6.6% of patients had a history of cardiovascular disease. Patients with hypotension were older, had a lower body mass index and waist circumference, and a more favorable lipid profile. Smoking and sedentary life style were less frequent. By contrast, the presence of cardiovascular disease (ischemic heart disease, stroke and renal insufficiency) was more common. In addition, patients with hypotension were taking more antihypertensive drugs than the other groups (17% were taking 3 or more antihypertensive drugs).

Mean values of systolic BP, diastolic BP and pulse pressure according to the presence of hypotension, good BP control and poor BP control.

| Overall | Hypotension | Good BP control | Poor BP control | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 12.961 (100) | 1.689 (13) | 6.510 (50.2) | 4.762 (36.7) | |

| Mean age (years) | 66.2±11.4 | 71.4±10.9 | 64.8±11.3 | 66.4±11.1 | 0.000 |

| Sex, male | 6.191 | 13.1% | 50.0% | 6.9% | 0.878 |

| Systolic BP | 135.8±14.4 | 126.2±14.9 | 128.5±7 | 149.3±11.7 | 0.000 |

| Diastolic BP | 79.2±9.4 | 64.1±4.5 | 78.2±5.3 | 85.9±8.2 | 0.000 |

| Pulse pressure | 56.6±12.8 | 62±15.6 | 50.3±7.6 | 63.3±13 | 0.000 |

BP: blood pressure.

Clinical characteristics of the study population according to the presence of hypotension, good BP control and poor BP control.

| Overall | Hypotension | Good BP control | Poor BP control | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | |||||

| Men | 83.2±12 | 78.7±12 | 83.4±12 | 84.7±13 | 0.021 |

| Women | 73.2±12 | 69.6±12 | 73±12 | 74.6±13 | 0.015 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.4±4.6 | 28.5±4.4 | 29.2±4.5 | 29.9±4.7 | 0.000 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | |||||

| Men | 102.2±12 | 101.1±13 | 101.4±12 | 103.7±12 | 0.008 |

| Women | 97.2±14 | 96.9±15 | 96.3±13 | 98.5±14 | 0.005 |

| Fasting serum glucose (mg/dl) | 109.3±31 | 109.6±30 | 106.6±28 | 113±34 | 0.000 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 203.5±38 | 192.5±38 | 201.9±36 | 209.7±39 | 0.000 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) | 53±14 | 53±15 | 53.1±14 | 52.8±14 | 0.578 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) | 124.9±33 | 115.3±32 | 123.9±32 | 129.7±35 | 0.018 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 136.8±67 | 128.5±64 | 132.9±61 | 145.3±7 | 0.009 |

| Obesity (%) | |||||

| BMI | 39.8 | 32.3 | 38.3 | 44.6 | 0.000 |

| Waist circumference | 60.8 | 58.1 | 58.5 | 64.8 | 0.000 |

| Smoking (%) | 16.6 | 9.7 | 16 | 19.8 | 0.000 |

| Sedentary life style (%) | 55.5 | 50.9 | 53.5 | 59.8 | 0.000 |

| Diabetes (%) | 30.9 | 36.1 | 27.3 | 34 | 0.000 |

| LVH (%) | 7.9 | 8.6 | 7.2 | 8.6 | 0.013 |

| MAU (%) | 15.5 | 16.1 | 11.7 | 20.6 | 0.000 |

| Carotid atherosclerosis (%) | 0.9 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.003 |

| Renal insufficiency (eGFR <60ml/min/m2) (%) | 21.5 | 33.3 | 17.8 | 22.3 | 0.000 |

| Creatinine >1.4/1.5mg/dl (%) | 3.8 | 7.1 | 3.0 | 3.7 | 0.000 |

| Stroke (%) | 4.5 | 6.6 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 0.000 |

| Ischemic heart disease (%) | 10.1 | 17.5 | 9.6 | 8.0 | 0.000 |

| Number of drugs | 1.53±0.7 | 1.70±0.8 | 1.46±0.7 | 1.56±0.7 | 0.012 |

| 3 or more drugs (%) | 10.9 | 17 | 8.6 | 12 | 0.000 |

LVH: left ventricular hypertrophy; MAU: microalbuminuria; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; BMI: body mass index; BP: blood pressure.

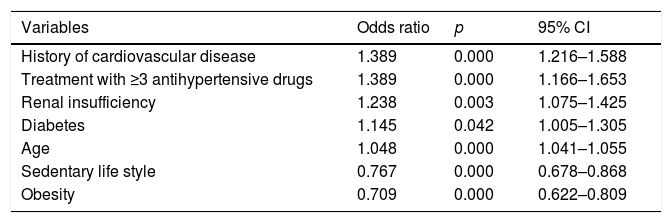

In the multivariant analysis, independent factors associated with the presence of hypotension were history of cardiovascular disease, treatment with 3 or more antihypertensive drugs, renal insufficiency, diabetes and age. On the other hand, obesity and sedentary lifestyle were protective factors (Table 4).

Variables associated with the presence of hypotension.

| Variables | Odds ratio | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| History of cardiovascular disease | 1.389 | 0.000 | 1.216–1.588 |

| Treatment with ≥3 antihypertensive drugs | 1.389 | 0.000 | 1.166–1.653 |

| Renal insufficiency | 1.238 | 0.003 | 1.075–1.425 |

| Diabetes | 1.145 | 0.042 | 1.005–1.305 |

| Age | 1.048 | 0.000 | 1.041–1.055 |

| Sedentary life style | 0.767 | 0.000 | 0.678–0.868 |

| Obesity | 0.709 | 0.000 | 0.622–0.809 |

CI: confidence interval.

In this study, the prevalence of hypotension due to antihypertensive drugs in hypertensive treated patients attended in Primary Care setting was analyzed.

Clinical guidelines do not clearly define hypotension,5,6 but orthostatic hypotension is defined as a reduction in systolic BP of ≥20mmHg or in diastolic BP of ≥10mmHg within 3min of standing.7 In addition, despite different clinical trials performed in hypertensive population included symptomatic hypotension as a side effect related with antihypertensive treatment, BP values defining hypotension were not given. Overall, the prevalence of symptomatic hypotension reported in these clinical trials was around 1–4%.15,21,27,28

In our study, hypotension was defined as a clinic systolic BP <110mmHg and/or diastolic BP <70mmHg. This definition was largely based on the results of PROVE IT-TIMI trial17 that showed that BP levels below these values could be harmful in patients with ischemic heart disease. Substudy of ONTARGET29 showed a nadir for diastolic BP around 72mmHg. In other study performed in patients >70 years old with known cardiovascular disease, an “optimal” diastolic BP of 70mmHg in subjects with isolated systolic hypertension was found.30 In a study that included subjects >85 years, a higher cardiovascular risk was observed in hose patients with systolic BP <120mmHg.31 In the study of Vamos et al.19 that included patients >18 years with a recent diagnosis of diabetes with or without cardiovascular disease, reductions of BP below 110/75mmHg were associated with an increased cardiovascular risk. In the study of Verdecchia et al.18 that was performed in patients with coronary artery disease, reductions of BP up to 118/68mmHg were associated with a decrease in the risk of stroke, but, importantly, without an increase in the risk of myocardial infarction.

In our study, the prevalence of hypotension in hypertensive treated patients was 13%, without significant differences according to gender. Hypotension was more common with diastolic BP (95% of patients) than with systolic BP (12.4% of patients). To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study to analyze the prevalence of hypotension in this clinical setting. In fact, the prevalence of hypotension reported in clinical trials comparing different antihypertensive drugs was limited only to symptomatic hypotension. As a result, the prevalence of hypotension reported in these studies may be lower than that observed in clinical practice, since many episodes of hypotension are not symptomatic and are detected when clinic BP is determined.

The prevalence of hypotension was higher in elderly patients and in those patients with coronary heart disease. Importantly, excessive BP reductions could be more harmful in these patients. Thus, in patients with coronary heart disease, such as those included in INVEST,15 TNT,16 and PROVE IT-TIMI17 trials, the existence of a J-curve was demonstrated. With regard to elderly patients, in the study of Protogerou et al.30 that was performed in patients >70 years, a higher risk was observed in those subjects with diastolic BP <60mmHg. Similarly, in the studies J-VALID32 and Iritani et al., 33 a J-curve was observed in hypertensive patients >75 years, but not in those <75 years. In other study performed in subjects >85 years, a systolic BP <120mmHg was associated with a higher mortality.31

In our study, the prevalence of hypotension was also higher in patients with stroke, renal insufficiency and diabetes. Other studies have also described the existence of a J-curve in patients with diabetes17,34 and renal insufficiency.35 Similarly, the PROGRESS36 and the SPS337 studies suggested the presence of a J-curve in patients with previous stroke.

Of note, the higher prevalence of high pulse pressure shown in patients with hypotension and in those hypertensive subjects with uncontrolled BP when compared to patients with a good BP control could be related with the greater arterial stiffness observed in these patients with high systolic BP. In this case, hypotension could be a consequence, particularly in elderly patients and in those with known cardiovascular disease.

On the other hand, the presence of hypotension in elderly patients or in those with cardiovascular disease could also be related with the presence of other comorbidities, such as malnutrition, chronic conditions or cardiac dysfunction that may increase the mortality risk.13,14 In fact, in our study, patients with hypotension were older and the presence of cardiovascular disease was more common. In the study of Gutiérrez-Misis et al.,38 only in those fragile elderly patients, a higher mortality risk was observed when systolic BP was below 120mmHg, but not in nonfragile elderly patients.

The presence of a J-curve remains controversial. Its existence could be related with the severity of some chronic conditions, or with a greater arterial stiffness and pulse wave velocity. In addition, it could be a marker of cardiac dysfunction or may limit myocardial perfusion, particularly when diastolic BP is excessively low.

In contrast to coronary perfusion, cerebral perfusion depends mainly on systolic BP, but not on diastolic BP. This could explain the dissimilar effects of the J-curve observed in different vital organs.

Although our study cannot explain the pathophysiology of the J-curve, it showed that the prevalence of hypotension was more common in elderly patients and in those subjects with cardiovascular disease. Our data suggest that hypotension could be a consequence in these patients.

The prevalence of hypotension could also be related with the higher use of antihypertensive drugs in these patients and this with a greater difficulty to achieve BP goals in elderly patients. The higher systolic BP levels and the higher use of antihypertensive drugs may lead to excessive reductions of diastolic BP. In addition, it also could be related with the greater efforts made by physicians to attain BP targets in patients with cardiovascular disease.

In the multivariant analysis, the variables associated with the presence of hypotension included the history of cardiovascular disease, the intensive antihypertensive treatment (3 or more drugs), diabetes, and age. By contrast, sedentary life style and obesity were protective factors maybe because that one of the possible causes for this, is that the control of the BP is more difficult in obese patients.

Our study has some limitations. Thus, since a white-coat effect could occur in some patients, the prevalence of hypotension could be underestimated. In this context, ambulatory BP monitoring and home BP monitory could be very useful. In addition, although in this type of studies a possible bias could occur regarding the BP determination, a single BP value with two PA measurements to minimize the alert reaction, It shows the hypotension in a point in time and we do not know if it is maintained over time, but the large sample size of our study could reduce this potential limitation. Another limitation of our study is the definition of hypotension chosen for our study. However, the definition of hypotension was largely based on the results of many clinical trials performed in hypertensive population, particularly with coronary artery disease,15–17,27–29 that identified a nadir similar to the cut points used in our study.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, only around 50% of patients with hypertension were adequately controlled. The prevalence of hypotension was high, particularly in elderly patients and in those with cardiovascular disease. One out of 4–5 elderly patients or with cardiovascular disease had hypotension. The prevalence of hypotension was related mainly with diastolic BP. This should be considered for the treatment of hypertensive patients, particularly in patients with coronary artery disease. On the other hand, our data suggest that hypotension may be the consequence in some patients such as elderly patients or those with cardiovascular disease. Future studies are required to determine whether hypotension is the cause or the consequence in these patients.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest.

To all primary care physicians investigators of the 2010 PRESCAP Study.

Adlbi Sibai A, Ajenjo González, M, Alonso Moreno FJ, Araujo Márquez L, Arina Cordeu C, Artigao Ródenas LM, Barquilla García A, Beato Fernández P, Caballero Pajares V, Cabezudo Moreno F, Calderón Montero A, Carrasco Carrasco E, Carrasco Martín JL, Carrizo Sánchez J, Cinza Sanjurjo S, de las Cuevas Miguel MP, Divisón Garrote JA, Elligson Garcia S, Escobar Cervantes C, Esteban Rojas MB, Fernández Toro JM, Frías Vargas M, García Criado E, Garcia Lerin A, García Matarín L, García Vallejo O, Genique Martinez R, Gil Gil I, González Casado I, Gorriz Teruel JL, Jimenez Baena E, Llisterri Caro JL, Martí Canales JC, Mediavilla Bravo JJ, Molina Escribano F, Morales Quintero S, Moyá Amengual A, Nieto Barco G, Pallarés Carratalá V, Piera Carbonell AM, Polo García J, Prieto Díaz MA, Rama Martínez T, Redondo Prieto M, Rey Aldana D, Riesgo Escudero BE, Rodríguez Roca GC, Rojas Martelo GA, Romero Secin AA, Ruiz García A, Sánchez Rodríguez R, Sánchez Ruíz T, Santos Altozano C, Sanz García FJ, Seoane Vicente MC, Serrano Cumplido A, Turégano Yedro M, Valls Roca F, Velilla Zancada SM, Vicente Molinero A.