In 1996, the NINDS (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Treatment of Acute Stroke) published targets for the management of patients with acute cerebrovascular events, setting a time of 3h or less for administration of thrombolytics, creating the Code Stroke.

ObjectiveEvaluate the time between onset of symptoms and arrival at the emergency department of a hospital as prognostic factors in patients with cerebrovascular events attended by the prehospital emergency medical service in the metropolitan area of Monterrey, Nuevo Leon.

Materials and methodsCalls received in the ED (EMME) between January and December 2012 were included in a retrospective cross-sectional study, with symptoms showing within the first 8h or with an unknown onset. The Mann–Whitney test and Fisher's exact test were used.

ResultsThirty-six patients were included in the study. In 21, the final diagnosis was cerebral infarction, 5 patients were treated with thrombolysis (23.8%). They were divided into two groups: group 1 died or were left with severe neurological sequelae (n=9) and Group 2 survived without sequelae or mild neurological sequelae (n=12). The door hospital arrival time was 67 (29–116)min (Group 1) versus 54 (24–86)min (Group 2) (p=0.110). The neurological status at the start of the event affected prognosis and mortality (p=0.018).

ConclusionsThere are few studies analyzing the time between the inception of the symptomatology and the arrival to the emergency room. In our study 23.8% of this series were thrombolyzed, which puts us in the range of international statistics, compared to the series published by Geffner-Sclarsky et al. The population of this study is small so it is not able to show statistical differences, but the few studies that evaluate the Code Stroke in Mexico open the doors to future work with a larger population in Latin American society.

Cerebrovascular events are the leading cause of disability and the second cause of dementia among adults.1 Stroke refers to the interruption of blood supply to the brain. If not treated in a timely manner it may cause permanent brain damage, having an impact on the patient's quality of life as well as his/her family. Cerebral ischemia is the most common cause of stroke, the most effective management treatment to define, and even revert, the damage is thrombolysis. In 1996, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Treatment of Acute Stroke published the goals for the management of an acute cerebrovascular event, establishing a time lapse of 3h or less for the administration of thrombolytic treatment.2 At this point, an early recognition and a rapid transportation of the patient to a specialized health care facility is vital; under 60min is the recommended time lapse. The shorter the transportation time is, the greater the possibility of recovery.3,4

From the emergence of the NINDS recommendations, several studies have been conducted trying to assess the compliance with timetables, finding a delay of 10–15min. Among these, we were able to find studies by Katzan, et al. in Cuyahoga County, 2003; Boode, et al. in 2007; Haraf, et al. in a multi-centered study in 2002; Schroeder, et al. in 2000; Salisbury, et al. in Oxford, 1998, and Lannehoa, et al. in 3 French emergency rooms in 1999.5–11 Thrombolytic treatment was only administered to less than 5% of the patients, becoming the main cause of pre-hospital/hospital delay,12 the main factors are the lack of recognition of symptoms by the patient and the lack of suspicion of a stroke victim by the medical personnel and the paramedics. The use of emergency medical services and the transportation of patients by them are associated with an earlier hospital admission and thus a better survival rate with fewer consequences for the patient.13–15 With the purpose of having a greater number of patients benefit from thrombolytic treatment, the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study ECASS-3 was conducted using rtPA with a widened window of 3–4.5h,16 with positive results.

Acknowledging the importance of the first 3h for the proper management of a stroke, the “The Code Stroke” was created. This code has been adopted in several countries worldwide. It is an organizational tool used to coordinate pre-hospital and hospital structures. Its main objective is to identify potential candidates for thrombolytic treatment and shorten transportation time as well as pre-hospital and hospital diagnoses.17 The activation of emergency medical services (EMS) and transportation is associated with early admission and better opportunities for the patient. The percentage of thrombolysis from activated the Code Strokes vary in different series between 12.9% and 26%, resulting in a better chance of a proper management for patients and the possibility to limit the sequelae, thus reinstating them into a normal and productive life.18

Studies have been published evaluating the time of arrival to the hospital and neurological attention in patients with acute stroke as shown in the study of EPICES. For example, The EBRICTUS study, which states that the implementation of a Code Stroke improves its attention in the whole territory, giving importance to pre-hospital attention.19–22

The Code Stroke has been installed in Nuevo León, Mexico. However, we do not have studies which evaluate its impact on timely attention for the population or in the prognosis, as proven in United States and European countries. For this reason, this study was conducted with the objective of evaluating the time elapsed between the onset of symptoms and arrival at the hospital ER, and its impact on the patient's final prognosis, to evaluate whether or not the background of chronic pathologies affects the patient's prognosis, and lastly, to determine the percentage of patients who reach thrombolytic treatment, as a means of evaluating the Code Stroke in our region.

Materials and methodsMedical Emergencies (EMME by its Spanish acronym) is an organization of mobile intensive therapy units (MITU) driven by a crew including a physician, a paramedic and a nurse, certified in Advance Cardiac Life Support (ACLS), for the service of patients in the metropolitan area of Monterrey, Nuevo Leon, Mexico.

The time between the onset of symptoms and the arrival at emergency services at a hospital were evaluated as factors of prognosis in patients with a cerebrovascular event, attended by pre-hospital medical emergency services in the metropolitan area of Monterrey, Nuevo Leon.

We used a retrospective, analytic, transversal, observational study, including all the calls received in our call center at EMME with patients who presented suspicious neurological symptomatology of cerebral ischemia within the first 8h between January and December 2012.

Inclusion criteria: patients who presented neurological alterations with data of lateralization at the moment of diagnosis (sudden weakness or paralysis, difficulty speaking, loss of vision, difficulty walking, loss of balance or coordination) between 18 and 80 years of age.

Exclusion criteria: patients who presented an evolution of symptoms of more than 8h, dependent patients (incapable of walking, cleaning or dressing themselves), patients who were asymptomatic at the time of the arrival of the ambulance, those with either terminal diseases, seizures at the onset of the stroke, or who presented any sign or symptom which made us think of a hemorrhage, patients who presented a medical background of digestive hemorrhage, intracranial hemorrhage and/or major surgery in the last three months.

Patients who, during their transportation to the hospital, showed any type of exclusion, or patients who refused to be transported to the hospital were excluded from the study.

All patients were evaluated at their address, using the Cincinnati Scale, by our mobile intensive therapy unit. Data was gathered from the service request reports registered at the company's call center, in addition to the patients’ clinical history and a survey performed via telephone to the patient or a relative.

We evaluated the association of time between the onset of symptoms and the arrival at emergency services at the hospital, with survival rate and the development of neurological damage, measuring the odd ratio with a 95% confidence interval. The results were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U-test and Fisher's exact test. We used the statistical software SPSS statistic 17.

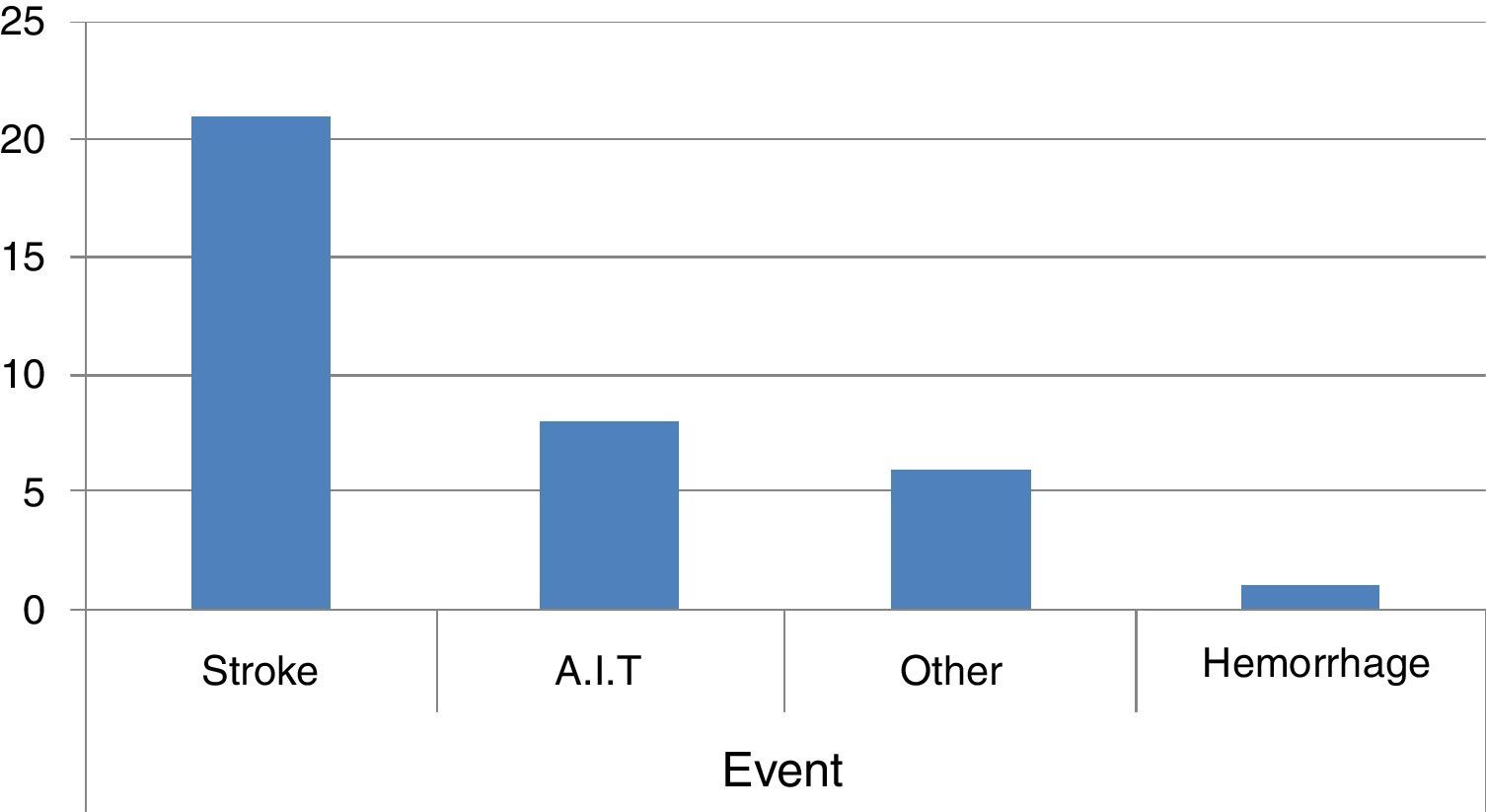

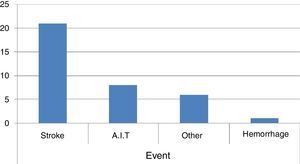

ResultsA total of 36 patients out of 118 were included. The remaining 82 were excluded because they did not agree to be part of the study or they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The patients presented neurological symptoms, cataloged as a probable cerebrovascular event, activating the Code Stroke. In 21 patients the final diagnosis was cerebral infarction, in 8 it was a transient ischemic attack, in 6 the diagnosis was diverse, including malignancies, metastasis and epilepsy. One patient presented a hemorrhagic event (Fig. 1). Out of the 21 patients with cerebral infarction, 5 were thrombolyzed.

The 21 patients with cerebral infarctions were divided into two groups. Group 1 included those patients who died or remained dependent on other people due to severe neurological sequelae. The group was formed of 9 patients, 7 men and 2 women. One male died.

Group 2 included those patients who survived with no or mild sequelae, thus allowing them to remain self-sufficient. The group was formed of 12 patients, 6 males and 6 female. There was no statistical difference in their ages, with a median of 75 (61–80) years of age for group 1 and 75 (63–79) years of age for group 2; gender distribution in group 2 was similar; however, in group 1 there was a male predominance (7 out of 9). This was not a factor associated with a negative prognosis (p=0.367). The time it took them to ask for help was an average of 30min (2–360min) for group 1 versus 30min (2–480min) for group 2 (p=0.309). The time of symptomatology onset to arrival at the hospital door was 67min (29–116min) for group 1 versus 54min (24–86min) for group 2 (p=0.110).

Response time and transportation to the hospital were within the first hour, which allowed for 23% of the transported patients to be thrombolyzed. This is due to the quick response on behalf of our medical service. Those patients who were thrombolyzed were distributed into both groups: 2 patients in group 1 and 3 patients in group 2. Nevertheless, thrombolysis did not improve the prognosis in these patients, since there was not a statistical difference.

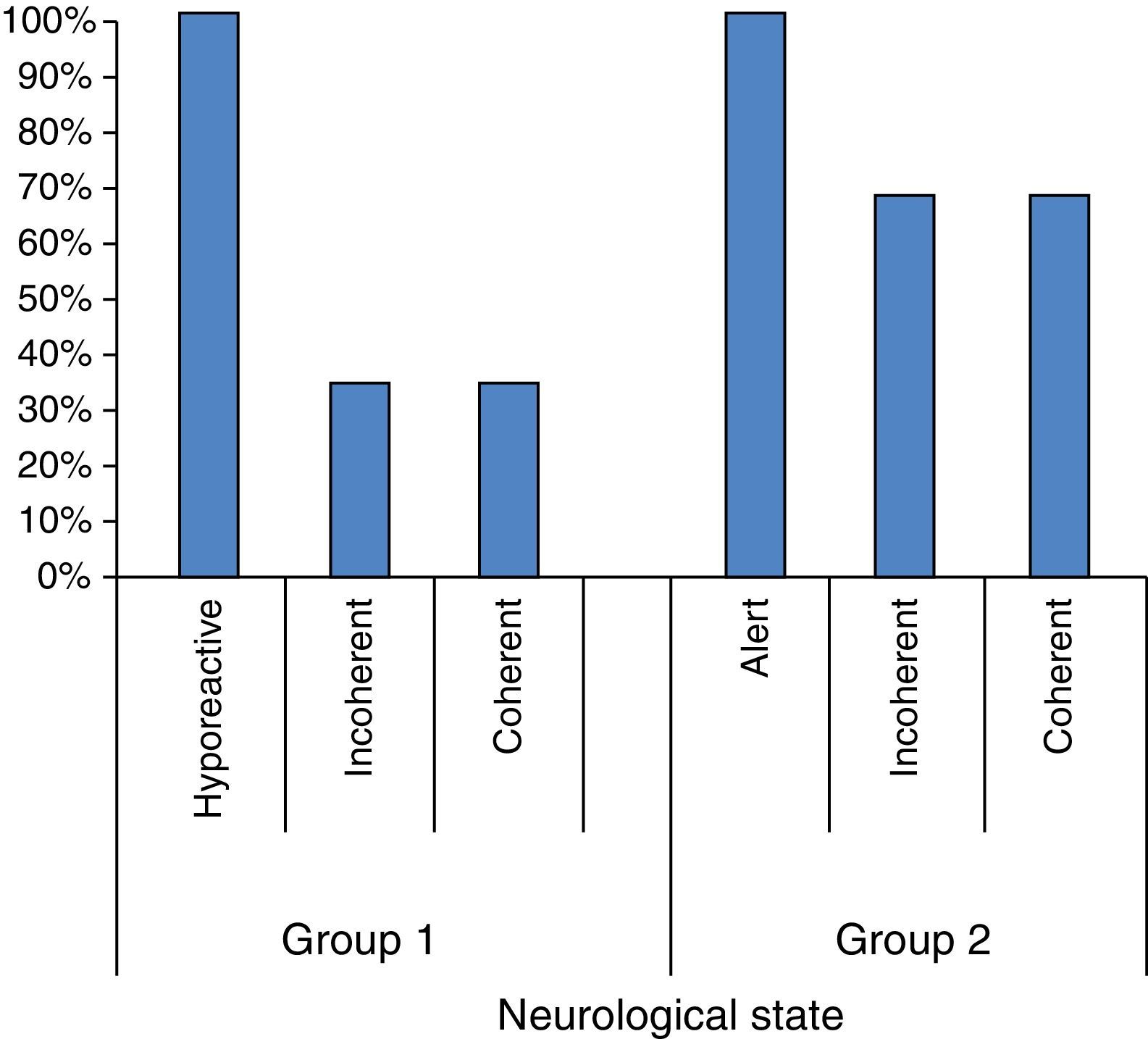

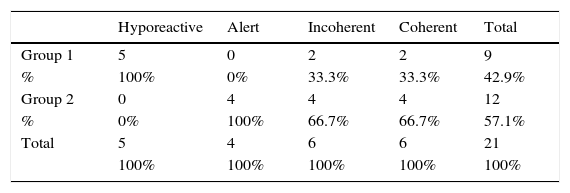

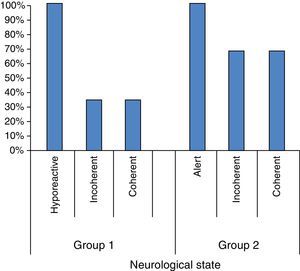

The neurological state of the patient evaluated by the pre-hospital service physician from the ambulance is shown in Table 1. We evaluated if the neurological state was related to the patient's result (Fig. 2).

The amount of hospital admission days was similar in both groups, with a median of 7 days (1–21 days) for group 1 and 7 days (1–40 days) for group 2. The neurological state presented by the patient at the onset of the event did have an impact on prognosis and mortality (p=0.018).

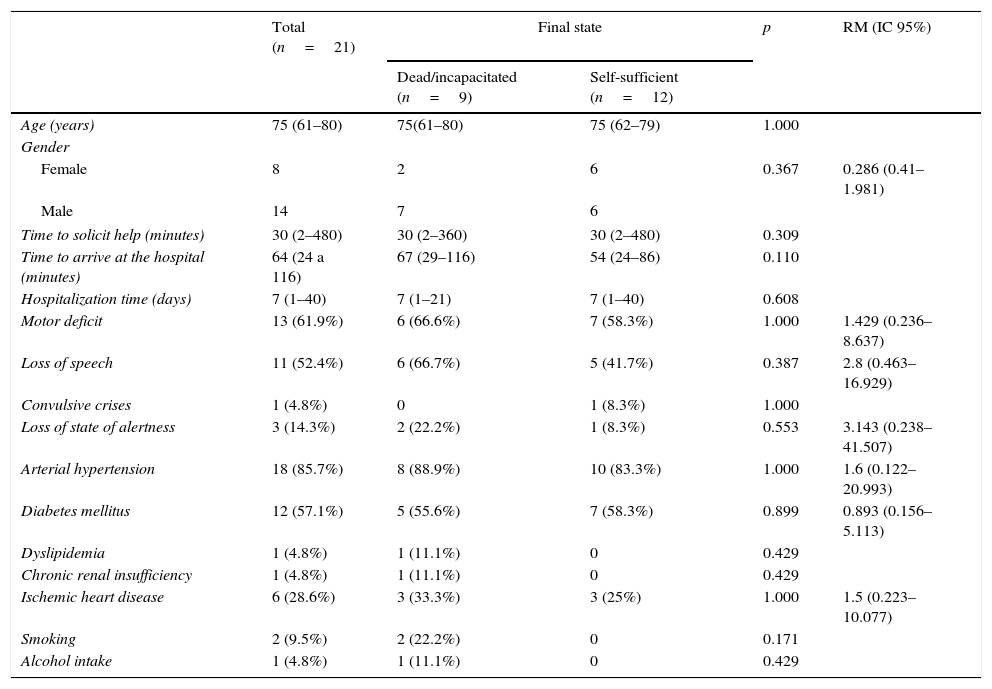

The presence of seizures, dyslipidemia, chronic kidney failure, high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease, smoking and drinking was analyzed; nevertheless, statistically these were not risk factors (Table 2).

Clinical characteristics of the state of 21 patients with a severe cerebrovascular event, from acknowledgment to final state, attended to by EMME emergency prehospital services in the metropolitan area of Monterrey, Mexico.

| Total (n=21) | Final state | p | RM (IC 95%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dead/incapacitated (n=9) | Self-sufficient (n=12) | ||||

| Age (years) | 75 (61–80) | 75(61–80) | 75 (62–79) | 1.000 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 8 | 2 | 6 | 0.367 | 0.286 (0.41–1.981) |

| Male | 14 | 7 | 6 | ||

| Time to solicit help (minutes) | 30 (2–480) | 30 (2–360) | 30 (2–480) | 0.309 | |

| Time to arrive at the hospital (minutes) | 64 (24 a 116) | 67 (29–116) | 54 (24–86) | 0.110 | |

| Hospitalization time (days) | 7 (1–40) | 7 (1–21) | 7 (1–40) | 0.608 | |

| Motor deficit | 13 (61.9%) | 6 (66.6%) | 7 (58.3%) | 1.000 | 1.429 (0.236–8.637) |

| Loss of speech | 11 (52.4%) | 6 (66.7%) | 5 (41.7%) | 0.387 | 2.8 (0.463–16.929) |

| Convulsive crises | 1 (4.8%) | 0 | 1 (8.3%) | 1.000 | |

| Loss of state of alertness | 3 (14.3%) | 2 (22.2%) | 1 (8.3%) | 0.553 | 3.143 (0.238–41.507) |

| Arterial hypertension | 18 (85.7%) | 8 (88.9%) | 10 (83.3%) | 1.000 | 1.6 (0.122–20.993) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12 (57.1%) | 5 (55.6%) | 7 (58.3%) | 0.899 | 0.893 (0.156–5.113) |

| Dyslipidemia | 1 (4.8%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | 0.429 | |

| Chronic renal insufficiency | 1 (4.8%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | 0.429 | |

| Ischemic heart disease | 6 (28.6%) | 3 (33.3%) | 3 (25%) | 1.000 | 1.5 (0.223–10.077) |

| Smoking | 2 (9.5%) | 2 (22.2%) | 0 | 0.171 | |

| Alcohol intake | 1 (4.8%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | 0.429 | |

Cerebrovascular events are the leading cause of disability worldwide, affecting the patient's quality of life, his/her family and society. In 1996, NINDS published the objectives for the management of patients with acute cerebrovascular accidents, establishing a time lapse of 3h or less in order to be able to offer the benefit of thrombolysis. This is the only procedure which has been proven to change the prognosis of the patient, a difficult task to achieve. The first publications showed that only less than 5% of patients were subjected to a thrombolytic procedure; therefore, the time lapse was extended to 4h, thus increasing the percentage to between 12.9 and 26%. The Code Stroke is created worldwide, due to pre-hospital management being of greater relevance for the patient's final prognosis. There are few papers which analyze this transportation time. The most relevant ones were conducted in Europe, mainly Spain. In the Americas, some of the most important studies analyzing the pre-hospital attention time lapse come from the U.S. Among the European studies, there is the series published by Geffner-Sclarsky, et al. in 2011 on the activation of the Code Stroke (pre-hospital as well as hospital) thrombolyzing 25% of the patients who activated the Code Stroke with a cerebral infarction, and which is among the international series which mentions that thrombolysis rate can be useful data to analyze the functionality of the Code Stroke systems. The work published in Latin America is scarce and studies where the functionality of the Code Stroke in Mexico is analyzed more so, hence this is one of the first to conduct said analysis.

Our study shows that 5 patients were thrombolyzed, corresponding to 23% of these series, which places us within international statistics, compared with the series published by Geffner-Sclarsky et al. Age was similar in both groups. There were no statistically significant differences in the time between pre-hospital attention and the hospital-door in both groups.

The amount of time in which pre-hospital medical attention was requested was shorter in group 1. One reason for this could be that these patients displayed a more severe neurological deterioration; however, thrombolytic procedure was similar in both groups and the amount of time from the onset of the symptoms to the activation of the Code Stroke was shorter in those who were not thrombolyzed.

The initial neurological state with which the patient was attended by the ambulance service does correlate to the patient's final prognosis, the more deteriorated the patient initially was, the worse the final result. This is because of the neurological damage secondary to cerebral hypoxia and an increase in intracranial blood pressure.

We included seizures among the variables analyzed as risk factors, since these occur when there is more severe neurological damage; a background of dyslipidemia or chronic kidney failure and a background of smoking and drinking were also included as risk factors, with a p lower than 0.05. None of the analyzed variables affected the prognosis in either group.

This can be the result of several factors, such as poor diffusion in our country of what a cerebrovascular event is and the importance of requesting immediate help. Additionally, specialized units intervene in the management of these type O patients, called Stroke units. These are a hospital organization located in a well-defined geographical area dedicated to non-intensive or semi-critical care of patients with stroke. They are integrated by a multidisciplinary, coordinated and trained team.

Despite the fact that the population in this study is limited, this is one of the few studies which evaluate the Code Stroke in our country, leading the way for future studies with a larger population in our Latin American society.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

FundingNo financial support was provided.