In order to appreciate mindfulness, it is necessary to focus on the concepts of non-judgement and acceptance as these attributes underpins the practice. Non-judgement is a label celebrated within a variety of helping professions and as a value at the core of much practice. In the context of mindfulness based interventions, accepting thoughts non-judgementally is an essential skill. However, the author argues against the ability of individuals to be non-judgemental given the profundity of its meaning and without other skills in place (without the practice of equanimity). The author puts forward a conceptual model of judgement and ‘naturally occurring ignorance’ in order to explore the potential barriers to practice. The author hypothesises that equanimity is the key mediating factor in being non-judgmental and therefore having the ability to generate compassion. A conceptual ‘cycle of judgement’ was created and discussed. Further, a theoretical model of ‘naturally occurring ignorance’ was created in order to confirm the barriers to equanimity, with the motivation of cultivating compassion.

Para valorar el mindfulness, es necesario centrarse en las ideas del no juicio (o imparcialidad) y de la aceptación ya que esto conceptualmente sustenta la práctica. El no juicio es una palabra importante en una variedad de profesiones de ayuda y un valour fundamental de muchas prácticas. En el contexto de las intervenciones basadas en el mindfulness, la aceptación de los pensamientos de manera no prejuiciosa es un ingrediente esencial. Sin embargo, el autor está en contra de la capacidad de las personas de ser imparciales, dada la profundidad de su significado. El autor presenta un modelo conceptual de juicio e «ignorancia presente de forma natural» para explorar conceptualmente las barreras potenciales a la práctica. El autor plantea la hipótesis de que la ecuanimidad es el factor mediador clave para facilitar la compasión. Se creó y se abordó un modelo conceptual de juicio. Además, se creó un modelo teórico de «ignorancia presente de forma natural» para subrayar las barreras a la ecuanimidad, con la motivación de cultivar la compasión.

It could be argued that the pace and scale of research coupled with the erratic media attention into the practice of mindfulness is beginning to take the buzz out of the buzzword. Although giant strides have been made in the field in recent years, a healthy scepticism has emerged (Hyland, 2014; Zizek, 2012). It is argued that the overlap of psychological constructs under the umbrella of ‘mindfulness’ prohibits, and, to some extent, distorts the transformative potential of mindfulness. That is, the transformative potential for mindfulness is facilitated by the intervention of the central psychological construct of equanimity. This paper suggests Mindfulness acts only as the first stage towards the cultivation of equanimity and that it is this complimentary practice that facilitates compassion and garners further research in isolation.

This article builds on the work of Desbordes et al. (2015) by clearly differentiating ‘non-judgemental acceptance’ and ‘attention’ within current mindfulness understanding. Although ‘acceptance’, and ‘non-judgement’, are significant, they do not fully capture the concept of equanimity. Furthermore, this paper highlights the necessity of researchers producing validated quantitative tools that seek to measure this construct and aids future researchers understanding of critical considerations when establishing self-report questionnaires. Moreover, interventions specifically aimed at cultivating equanimity should be promoted via EEG in order to accurately assess this multi-dimensional construct.

Clear distinctions made between the ‘attentional’ faculties of mindfulness and the realm of ‘non-judgmental/acceptance’ or ‘equanimity’ would build on Lindsay, Young, Smyth, Brown, and Creswell (2017) pioneering mindfulness dismantling study. The study exemplified participants whom had both attention monitoring and acceptance mindfulness training experienced a greater reduction in mind wandering relative to other conditions including attention itself. This, for the first time highlights acceptance as a critical driver in the reduction of mind wandering, which is significant, given the challenge to describe and measure the effects of meditation and to explain their relevance for health and well-being.

Though there is a wide breadth of mindfulness studies, each to some extent reflects the authors’ personal interests and expertise. An abundance of mindfulness scales have been introduced in line with the exponential growth of the discipline in recent years. ‘Paying attention to the present moment without judgement’ (Kabat-Zinn, 2003) is widely accepted as one of the leading definitions. Yet on closer inspection, it is clear this working definition encompasses two separate elements, with one being the clear development of ones attentional capacity (paying attention to the present moment) and the other, a non-judgmental experiential attitude towards phenomenon (without judgement).

Various western definitions of mindfulness highlight a common component of mindfulness as an ‘attitude of openness and acceptance’. Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, and Toney (2006) defines it as “a state of being in which individuals bring their attention to the experiences occurring in the present moment, in a non-judgmental or accepting way” (p. 27); an adaptable state of consciousness that encompasses receptive attention and awareness of one's inner state and the outside world, regardless of whether these encounters are positive or negative (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Brown, Ryan, & Creswell, 2007). The aforementioned work has resulted in a worldwide surge of interest in Mindfulness based interventions in a variety of sectors. There have been a number of studies that have looked at the value of mindfulness based interventions in managing such states as stress reduction, depression and general anxiety disorder (Baer, 2003; Carmody & Baer, 2009; Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt, & Walach, 2004; Teixeira, 2008; Toneatto & Nguyen, 2007).

In consideration of mindfulness based training's (MBT's) wider application to various sectors, Bishop et al. (2004) recommended a dual functioning operational definition, one that encompasses ‘the self-regulation of attention so that it is maintained on immediate experience’, and secondly, ‘an orientation that is characterised by curiosity, openness, and acceptance.’ Here, the distinction between ‘paying attention’ and ‘non-judgementally’ is clearly categorised, however it is worth mentioning this was later criticised for confusing attention with awareness (Rapgay & Bystrisky, 2009).

Several reviews of the scales have been conducted (Baer, 2011; Bergomi, Tsacher, & Kupper, 2013; Park, Reilly-Spong, & Gross, 2013; Sauer et al., 2013) which have highlighted different structures and emphasise different aspects which reflect different understanding of mindfulness. Only one scale the Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory scale (FMI) was largely influenced by the mindfulness practice found in Buddhism but still includes the contemporary understanding of mindfulness (Walach, Buchheld, Buttenmuller, Kleinknecht, & Schmidt, 2006). The clear inconsistency caused by differing factors suggest the possibility that current mindfulness scales may measure aspects that do not match the elements found in traditional mindfulness meditation, namely an emphasis on equanimity as the foundation for mindfulness practice.

The practice of mindfulness originates from Eastern spiritual, particularly Buddhist, traditions described as the process of paying attention to an object in working memory (Shulman, 2010). It seems apt to return to the Eastern context given Mindfulness's original point of dissemination. Revisiting the Sanskrit term for mindfulness as the ‘quality of mind that recollects continuously without forgetfulness or distraction while maintaining attention on a particular object’ (Dreyfus, 2011). This clearly mirrors Bishop et al. (2004) and Kabat-Zinn (2003) first part of the definition. However, it is evident; there is little mention of there being a ‘non-judgemental’ attitude, pointing towards the understanding that being ‘non-judgemental’ or ‘acceptance’ has perhaps been included in the western definition but that this has not garnered equal attention. The distinction is consolidated by Zeng, Oei, Ye, and Liu (2015), whom refer to the practice of Goenka's Vipassna Meditation (GVM) that constitutes an enhancement of ‘awareness’ which refers towards bodily sensations and associated emotions, and then ‘equanimity’, which refers to the attitude of acceptance towards bodily sensations or emotions (Hart, 1987). The question arises whether the majority of current mindfulness measurement merely represent attention or memory scales rather than reflect the deeper and more profound depth of the practice.

In Buddhism, Mindfulness is a key part of developing compassion in self and others and ultimately part of a much larger psychological process which includes the development of qualities such as loving kindness (metta), compassion (karuna), joy (mudita), and equanimity (upekkha). These qualities are cultivated towards self and are extended towards friends, neutral individuals, and difficult people and finally to all living beings (Thera, 1994; Zopa, 2013). It is hypothesised that the attitude of compassion, acceptance, open and non-judgemental curiosity in Mindfulness revolve around these four qualities, but ultimately relies on equanimity as the mediating variable.

The East and West divide is exacerbated by Baer et al. (2006) whose study investigating the structure of facets within five key mindfulness scales found that mindfulness is a multi-faceted construct comprising of non-reactivity, observing, awareness, describing and non-judging. Although The Toronto Mindfulness Scale (TMS) (Lau et al., 2006) includes two factors of decentering and curiosity (including items mentioning openness and acceptance), this does not explicitly measure loving kindness, compassion, or joy. Only one measure has directly attempted to capture compassion with the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) (Neff, 2003) however this solely focusses on the self. The only scale currently looking at facets of mindfulness such as compassion and loving kindness is the ‘Self-Others Four Immeasurables’ (SOFI) developed by Kraus and Sears (2009). This was designed in order to measure loving-kindness, compassion, joy and acceptance towards both self and others.

Returning East and conceptualising EquanimityIt is important to note that in Buddhism mindfulness and equanimity are given clear distinctions. Equanimity has been described as “a state of mind that cannot be swayed by biases and preferences; an even mindedness in the face of every sort of experience regardless of whether pleasure (or) pain are present,” (Thanissaro, 1996, p. 262). That is, one experiences mental states with equal interest without repression, denial or judgement. In Buddhism ‘equanimity’ or (upeksha in Sanskrit) contains multi-dimensional constructs and for the purpose of this paper the author defines equanimity as a mental state that requires practice and manifests as “a balanced reaction to joy and misery” (Bodhi, 2000, p. 34). Therefore an element of impartiality is achieved so that when unpleasant thoughts arise, an individual is able to attend to them without denial, repression or aversion. Similarly, when pleasant thoughts arise, one is able to attend to these without becoming over-excited or trying to prolong these, or becoming addicted to them (Grabovac, Lau, & Willett, 2011). In Tibetan Buddhism this inner cultivation of equanimity is referred to as the Hinayana attitude, and that the Mahayana attitude is then cultivated when this attitude is extended towards all beings (friends, enemies and strangers) without the superficial boundaries that we habitually create (Yeshe, 1998).

It is imperative to differentiate that equanimity is not apathy or “indifference but rather of mental imperturbability” (Thanissaro, 1996, p. 263). The Dalai Lama (2001) asserts equanimity really does allow you to be free from being caught up in the play of emotions. Not only is equanimity the cultivation of an even minded response to all experience, but also involves the practice of maintaining calm in the face of provocative stimuli (Carmody & Baer, 2009). It is here that the concept lends itself to emotional regulation as equanimity can alter both the quality and magnitude of responses (Gross & Thompson, 2007). Thus, research into equanimity in isolation from mindfulness is key in establishing adaptive processes that may aid neurocognitive, psychological, physiological and behavioural mechanisms.

Equanimity is distinguished by lack of strong liking (attachment), aversion (dislike) or neutrality towards phenomenon and is characterised by steadiness of mind under stress, being calm and even-tempered. It is a balanced state of mind that is evoked by the process of mindfulness. It does not mean indifference but a vehicle to connect from a point of genuine affection rather than bias subjection. Thus, by developing equanimity it could be argued that equanimity becomes the foundation for self-compassion and compassion for others. An equanamous attitude towards one's own transient experience and then towards others could be separated into two subscales. Firstly, as an experience towards one's own perceived reality, in mindfully attending towards phenomenon one deploys equanimity in order to allow things to come and go and to be removed from emotive responses. Then paradoxically, this hallmark is transferred towards others that highlights a more objectively compassionate outlook on reality.

This is significant for Western psychology as the term equanimity has not garnered much discussion, however appears strongly related to the context of mindfulness. The closest concept of equanimity in the West can be seen in the psychoanalytical approach where emotions are observed as ‘even minded’ without condemnation with free-floating attention. Therefore, it could be said that mindfulness encompasses components that may better be characterised as equanimity. Equanimity manifests a balanced reaction to the joys and miseries of mental experience that protects the mind from emotional agitation, which highlights its significant in emotional regulation but also as a vehicle for cultivating compassion.

Mindfulness in this instance invites the ability to remain consciously aware of experience, whilst equanimity allows this awareness to be unbiased by facilitating an attitude of non-attachment, aversion and ignorance. Ultimately, this process acts a facilitator for compassion given certain levels of discernment, so it seems critical to measure the connection between mindfulness, equanimity and the cultivation of compassion. Multiple measures exist that examine the attentional, awareness and non-judgement aspects of meditation practice, but measurement of the compassion component is again lacking.

Furthermore, a subtle level of discernment is promoted within Buddhism in line with ethical codes (Dunne, 2015). A dispositional tendency of equanimity that is developed over time via specific practices is less challenging than ‘non-judgement’ and ‘acceptance’ that is applied when being ‘mindful’ then potentially abandoned when out of practice. This could tackle key questions around ethics, such as how do you live a mindful life without judgement when the majority of humankind lives by moral or ethical codes of conduct. We naturally judge and because of this may experience challenges and have a harder time accepting certain things over others. The answer to these questions could be that we do not accept all things non-judgementally but we develop equanimity instead. Thus a certain level of discernment towards phenomenon such as compassion, empathy and loving kindness for example remain present depending on your philosophical paradigm. The differentiation is consolidated by Grossman (2015) “The factors that co-arise with mindfulness under all circumstances also help define it and refine how it functions in the mind. Generosity (alobha, from the Pali) and kindness (adosa) help clarify that mindful attention neither favours nor opposes the object, but rather expresses the quality of equanimity. This is where modern definitions of mindfulness get the sense of not judging the object but of accepting it just as it is.”

Linkages between mindfulness, equanimity and compassionCompassion ascends via a plethora of emotions, motives, thoughts and behaviours. Therefore, rather than agreeing on a single definition of compassion the author promotes the idea that cruelty decrees compassions antithesis. That, the desire to alleviate the suffering of others, or the care-giving mentality (Bowlby, 1982) that underpins compassion act as core components of the construct (Gilbert, 2005). This is in line with Bierhoff (2002) distinction that the notion of compassion is inextricably linked to pro-social behaviours of an action intending to improve the situation of the help-recipient. It is therefore reasonable to postulate that compassion evokes a sense of interconnectivity with humankind.

Indeed, in Buddhism, two key elements; that of developing mindfulness and cultivating compassion have crossed swords with Western science (Davidson & Harrington, 2002) yet little attention has been given to examining how these states emerge from and impact our physiological systems. Indeed, Wang (2005) research into physiological systems leads to the conclusion that compassion is dependent on a unique type of awareness beyond the self but that is inclusive of others. The author postulates that equanimity disarms the strong distinction between self and other and acts as a facilitator to cultivate compassion. Only through the softening of a strong sense of ‘like’/‘dislike’ which is projected onto the ‘other’ can compassion deepen both within oneself and towards others.

This would ameliorate the potential discomfort that compassion can manifest which is exemplified by Condon and Barrett (2013) whom demonstrated in their study that participants felt increased levels of unpleasant affect when faced with increasing levels of suffering. Their research highlights how experiences of compassion were unpleasant when exposed to another's suffering, or pleasant towards neutral indicators. Interestingly, differentiated experiences of compassion open up the possibility for equanimity to take centre stage. As compassion is seemingly conceptualised as pleasant yet may manifest as a difficult emotion, it is here an equanimous approach towards one's own sense of ‘unpleasant’ may ameliorate this dichotomy. The authors concluded that similarly to leaving the environment when experiencing anger, a pleasant, calm experience of compassion might best facilitate the reduction of another's suffering, opening the primary objective of contemplative practice in inducing calm compassion in the face of another's suffering. Again, it is postulated that the optimum experience of calm compassion is derived from an individual manifesting foremost equanimity, so that when faced with a situation, regardless of pleasant, unpleasant or indeed neutral one is best able to cultivate compassion on the basis of this quality.

Cameron, Payne, Sinnott-Amstrong, Scheffer, and Inzlicht (2017) compound this further by citing that implicit moral evaluations of the wrongness of actions or people plays a key part in moral behaviour. Regardless of the principles on which they are based an individual deploys intentional judgement or unintentional judgement eliciting the variability of moral cognition. This is further evidence to support the need for analysing judgements and harbouring equanimity by suggesting equanimity could enable individuals to cope with the aversive nature of compassion by cultivating even-mindedness.

Compassion is something we can achieve and nurture once we have a grasp of what it is to non-judge and accept phenomenon as transient moments in time rather than a fixed and ridged reality. Without a fully working model of judgement that indicates the barriers one is up against, the practice of mindfulness could be relatively superficial as one is unable to fully manifest equanimity let alone understand it. “When we practice judgement and criticism, we strengthen neuropathways of negativity, conversely, when we practice equanimity, openness, and acceptance, we strengthen our capacity to be with whatever arises in our field of experience, negative or positive.” (Shapiro, De Sousa, &, Jazaieri, 2016, p. 109, cited in Ivtzan & Lomas, 2016). The model proposes barriers of judgements that prohibit the practice of mindfulness, equanimity and compassion.

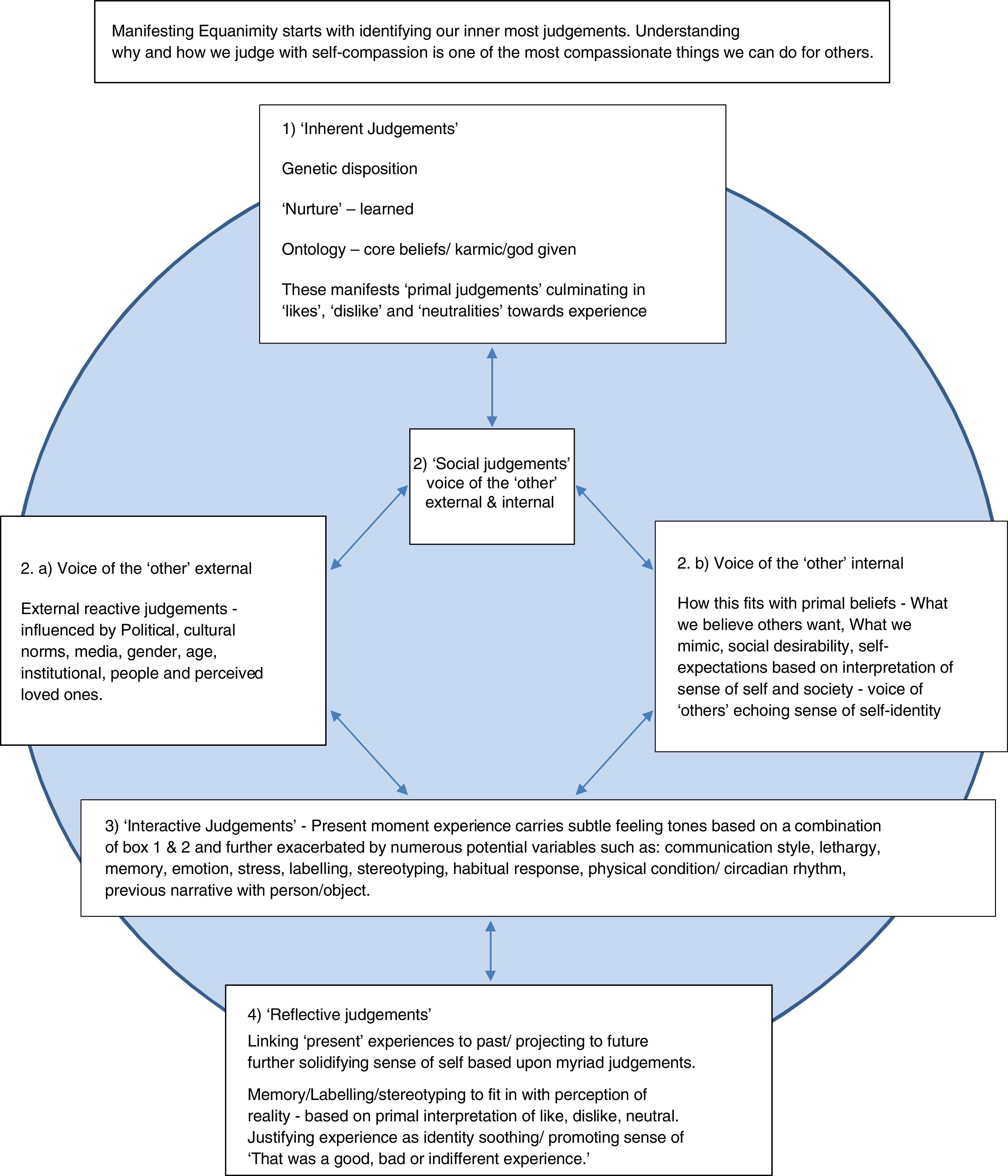

The Cycle of Judgement: Barriers to Equanimity (Fig. 1)Human experience is with judgement and it is postulated that human judgements (likes, dislikes or feelings of neutrality) come from several sources both on an individual level and from the social world we interact with. The model attempts to highlight the ways in which we develop judgements towards phenomenon.

Innate level of judgementThe innate level of judgement refers to what an individual comes into the world with, their genetically pre-determined/or nurtured basic feelings of like, dislike and neutrality. These base notes determine how an individual relates and interacts with the world. One could refer to these base notes as primordial layers of judgement. Therefore, one could argue that the propensity of judging begins via the gene-environmental interaction manifesting as conscious or unconscious judgements towards phenomenon. At this stage a person has an innate sense of judgements towards things depending on physiological functioning. On a purely observational level this is evident in babies displaying preferences for things, people, attachment figures and emotions.

Social judgementsThe next stage of the model attunes to the social world. That is to say the innate judgement sphere gives a propensity of judgements, but that these can be potentially altered or exacerbated via the social world. The social level of judgement involves a two component view on how the social world moulds and shapes a person's sense of judgement as well as being projected onto the social world by the individuals’ base judgements. The external and internal judgements play out a conflict type battleground for assumed power. Here the individual conveys a set of internal judgements that are either reinforced or challenged based on the propensity of social conditioning. This can either solidify core judgements onto a more unconscious level, yet also can be changed via the tenacity of experience and personality in question.

External judgements refer to the myriad possibility of institutions or agencies that can manipulate or give rise to conscious or unconscious judgements towards phenomenon. Whereas internal social judgements refer to the tender aspect of sense of self that seeks approval and acceptance from others. Here an individual can manipulate or give rise to judgements in order to suit the voice of the ‘other’, and paradoxically develop a strong sense of judgement based on this. This highlights the threat of individuals suffering low self-esteem, confidence or severe non-awareness formulating judgements based solely on the desire to ‘fit in’.

Interactive judgementsThe judgemental level of interaction is particularly evident in the context of mindfulness. Here the author postulates the majority of inner judgements accumulated via the innate and social layers colour and to a certain extent pre-determine the outcome of present moment experience. Such is the well-documented manner in which the mind conducts itself via mindfulness interventions and research. Mindfulness here becomes the concept to help understand the reality that an individual spends a considerable amount of time within, not in the present moment, lost in the conceptual mind therefore lost in dominant judgemental modes of being.

Reflective judgementsFinally, a reflective judgement layer is created in order to signify that even post experience an individual categorises and theorises an experience as ‘good’, ‘bad’ or ‘neutral’, leaving the inner judgements to reaffirm power over present felt experience, colouring future experiences in order to comply with an individual's self-construct. Here the individual relates experience to both the innate level, social and ‘present’ moment experience to assign meaning to the experience. Counter intuitively this can however, without equanimity, stunt reflective progression and reinforce pre-existing maladaptive behaviour. Post event the experience will be categorised on a conscious/unconscious level (in sync) with previous layers of judgement so the ‘self’ remains in a state of control. The judgement cycle highlights the potential layers of judgements upon us so points towards the need to work on the ego or sense of self.

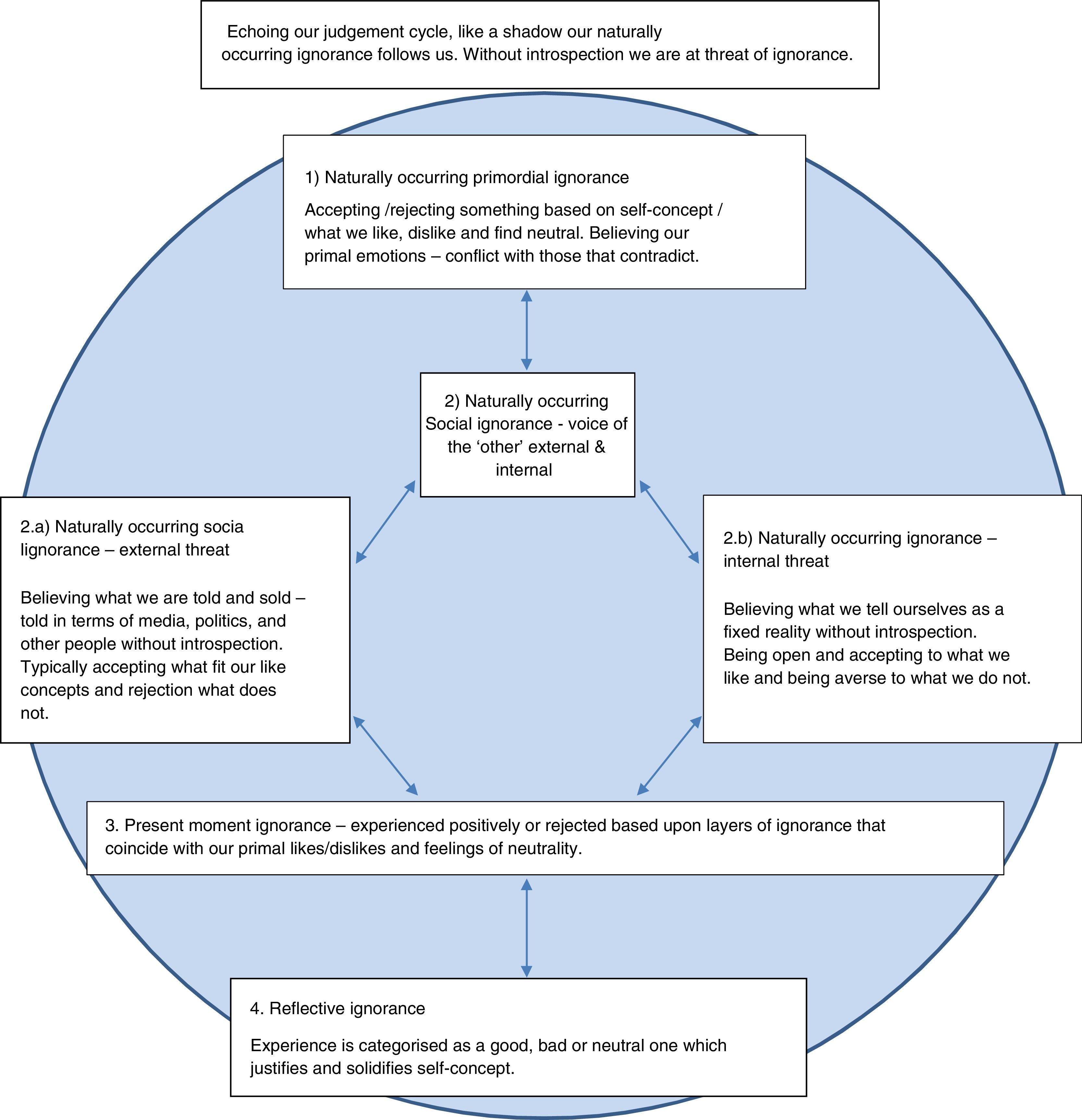

The Cycle of Naturally Occurring Ignorance (Fig. 2)It is theorised that due to an individual's complex layers of judgement a certain experiential ignorance/non-awareness runs in sync with a person's ego identity. Like a shadow following the body, non-awareness manifests in terms of justifying, reaffirming and complying with perceived judgements, opposing worldviews are dismissed naturally via the ego's defence (Goleman, 2015; Wallace, 2011). A certain naturally conditioned ignorance shades an individual's development over time. Not always an ignorance in the sense of a deliberate rejection, but an ignorance manifest due to the egos self-serving nature, rejoicing in perceived likes or good experiences, accumulating stress or anger towards negative experiences and categorising others as neutral and neither threatening or pleasurable, and therefore irrelevant. This is to suggest that we are self-serving based upon pleasurable and un-pleasurable experiences and are only ‘happy’ provided we encounter the pleasurable ones. This unfortunately suggests we are bound to individualism and self-serving feelings supportive to those created by our own judgement cycle. Hostility towards others therefore becomes a natural unavoidable experience should we ignore the essence of our being and instead listen to the ego (Chodren, 2014; Lama et al., 2012).

Driven from our base feelings we subsequently encounter naturally occurring ignorance in relation to our fixed sense of self. Thus the process of one's life may be about unpicking the layers of ignorance in relation to oneself. The link between liking and disliking something means you are automatically judging reality based upon a subjective context which does not fully appreciate that judgements are merely transient expressions of subjective causes and conditions and not a fixed and rigid ‘reality’. Ricard (2015) notes that one should adopt a joyous attitude of acceptance, to that of the good, the bad and the neutral. With the development of mindfulness based equanimity we can increase our ability to manage and master the ego “self” driven thoughts, emotions and actions that can dominate and increase our problems in relationships with others. Our natural development of compassion that arises when we view humanity as united and similar is based on an equanimous world view. Without equanimity, mindfulness can just be a selfish pursuit.

It is postulated you cannot separate compassion and mindfulness as without mindfulness you will still have lack of awareness controlled by your base feelings. Compassion therefore could become orientated around your likes and dislikes rather than a true sense of the term. Mindfulness calms the mind so qualities like compassion can be nurtured. Equanimity provides the emotional regulation of balance so we remain steadfast and lean towards compassion regardless of experience.

Judgement is therefore closely attuned to ignorance (as per the cycle 2). In sum, we are ignorant beings based upon limited subjective interpretation who are defined and nurtured by our environment but hold significant rigid and fixed views of reality as truths that are mere reflections of a manufactured reality. It would seem therefore, that we each create our own reality. Therefore the interdependence between ignorance and judgement must be attended to in order to move beyond mindfulness and truly be able to accept things non-judgementally and harbour an attitude of equanimity to all phenomenon in order for compassion to grow and be nurtured within us. This is the true challenge of an introspective practitioner.

DiscussionSinclair et al. (2016) conducted a systematic review over the past 25 years of compassion in healthcare and highlighted that 40% of studies identified barriers to providing compassionate care across the clinical, healthcare and education sectors concluding that understanding of the nature of compassion is underdeveloped and there are significant barriers to its practice. This is exacerbated when taking into consideration research suggesting it is not just the absence of compassion that is significant in todays’ society but also the fear of compassion (Gilbert, McEwan, Matos, & Rivis, 2011). Dynamically resisting engagement in compassionate experiences should be a major concern in an increasingly competitive society (Gilbert, 2009), as Governmental reports such as the Francis Report (2013) indicate, there are major concerns surrounding compassion in health systems internationally. The decline in compassion and empathy is compounded further by Konrath, O’Brian, and Hsing (2011) whom exemplified that over time, individuals experience a lessening of empathic concern and perspective taking towards others. Worryingly, this was a more recent phenomenon as the experience was more distinct in samples post the year 2000 (Shonin, Van Gordon, Compare, Zangeneh, & Griffiths, 2014). Todaro-Franceschis’ (2012) work on compassion fatigue and burnout in nursing would support this claim. It is imperative to consider that compassion is not a quality that you either have or do not have but one that is inherent and just needs nurturing.

It could be argued that current mindfulness scales reflect a bias towards attentional and memory dispositions, whereas the notion of accepting things without judgement is underrepresented. In order to explore the profundity of the practice perhaps a reliance of the knowledge of the teacher is assumed within interventions. Yet, without adequate care, accepting things without judgement as alluded to by previous commentators, can have a maladaptive affect. Such is the relative ease and human ability to suppress, repress and deny phenomenon that occur in consciousness it appears acceptance itself and the second part of the definition ‘attending to things non-judgmentally’ demands more attention. It is in this vein, that exploring equanimity seems the most appropriate. Given the lack of attention to the subject in academia, it is therefore fundamental that separate, working definitions and models are conceptualised. Thus, journeys into the self, via mindfulness and equanimity can provide a smooth transition into the cultivation and subsequent development of compassion.

Should an adequate intervention conceptualise equanimity in the west, as a usable and valid construct then future mindfulness studies will reflect not only the ability to enhance memory and attentional capacity but also reflect the profound nature of the practice which is to generate self-compassion and compassion through the ability to be present in the moment nonjudgmentally. The qualities of compassion can be accessed through research into mindfulness and equanimity. Not only will the measurement aid the impact of mindfulness interventions, but enhance individual and cultural wellbeing by shifting focus into the compassionate element of the practice both in self and others. This moves mindfulness and in particular research into new areas such as the nature of acceptance, how to actively generate compassion, and also how to sustain mindful practice once a typical intervention has ended. This could provide a robust linkage between mindfulness interventions and compassionate based interventions such as compassion cultivation training (CCT) (Jinpa, 2015).

Equanimity is not independent of mindfulness, as one must be mindful of states of mind in order to relate the attitudinal concept of equanimity. Yet it is not dependant on mindfulness in that it can be applied as a general philosophy in life. In becoming mindful we steady the mind in its natural mode without thought or distraction. In order to maintain this awareness and abide in evenness we deploy the attitudinal hallmark of equanimity. Thus, regardless of sensory or mental phenomenon the attitudinal aspect of equanimity enters awareness and is used as a tool to rest the mind in continual steadiness. That is, what emerges in awareness is observed without a strong sense of like, dislike or neutrality. It is here, in the balance between non-judgement and acceptance that are hallmarks within western definitions of mindfulness that equanimity has its place. Equanimity has a role in emotional regulation and that these processes are facilitated via the cultivation of equanimity and mindfulness. This enables an individual to increase ones holistic sense of compassion and combat the likelihood of compassion fatigue for example. Furthermore, the likelihood of generating compassion in challenging contexts is strengthened.

The value of equanimity is that difficult and also pleasurable experiences are given equal attention (acceptance) and instead of reactions to thoughts or feelings (non-judgement) the mind is regulated by mindfulness from the multi-dimensional aspects of awareness of phenomenon arising, continual attention to such experience without distraction and finally with an attitude of equanimity. Through mindfulness what is learned is how to non-reactively observe, de-centre from thoughts and assume an open spirit of curiosity. The focus on the breath enables an individual to accept the neutrality of breathing itself and de-centring enables one to detach from painful or unpleasant experiences. Thus the skill of equanimity is created, that is the ability to detach from emotions and thoughts and view all mental phenomenon as transient mental events rather than decisive descriptions of reality that have a hold over the individual. By changing the relationship to ones’ thoughts and emotions then healthy thoughts and feelings are given space to develop (Weber & Taylor, 2016).

Such is the plasticity of the human brain, learning to recognise, observe and detach from thoughts is the fundamental relief from undesirable feeling. Previous measures appear to focus on attention, whereas the SOFI scale (Kraus & Sears, 2009) scale focusses on how this attention is applied. The scale is the first that measures the aspirational qualities associated with mindfulness and is unique in that it focus is towards others as well as self so the author advocates more research in this area.

This paper has conceptualised a working model of judgement and proposed a theoretical model of ignorance in order to further research in contemplative traditions. Equanimity can be used to examine the correlates between mindfulness and compassion that will thrust contemplative practice into unexplored territory. This could endeavour to progress research on self and identity as well as attitudes towards others. Projects on social cohesion, enhancing understanding of others, prejudice, hatred and bullying may benefit from measuring positive combined with negative aspects of self and other judgements both in mindfulness, positive psychology, peace studies and healthcare settings.