Both researchers on mindfulness, as well as proponents of therapy modalities that incorporate mindfulness-based skill building, typically conceptualize the stress reducing benefits of mindfulness primarily to its ability to modulate maladaptive cognitive or attentional patterns. Naïve dialecticalism (i.e., a less synthesized and integrated tolerance of apparently contradictory or ambivalent beliefs) represents an approach to cognition that is associated with greater self-criticism and inconsistency within one's global self-concept and is thus theorized to be negatively related to mindfulness. The present study investigated whether the beneficial effects of mindfulness on cognition (i.e., lower levels of naïve dialectical thinking) are in fact accounted for via the beneficial effects of mindfulness on one's relationships (i.e., enhanced perceptions of adult attachment security). Structural equation modeling demonstrated that adult attachment security in fact fully mediated the negative relationship between naïve dialectical thinking and mindfulness. These results highlight an understanding of mindfulness meditation as a practice that cultivates not only harmonious affect and cognition, but also harmonious relationships with others.

Tanto los investigadores sobre el mindfulness como los defensores de modalidades de terapia que incorporan el desarrollo de destrezas basado en el mindfulness suelen conceptualizar el estrés principalmente como reductor de los beneficios del mindfulness a su capacidad de modular los patrones mal adaptativos cognitivos o atencionales. El dialecticalismo ingenuo (es decir, una tolerancia menos sintetizada e integrada de creencias aparentemente contradictorias o ambivalentes) representa un acercamiento a la cognición que está asociado con mayor autocrítica e incongruencia en el autoconcepto global y, por tanto, se teoriza como relacionado negativamente con el mindfulness. El presente estudio analizó si los efectos beneficiosos del mindfulness sobre la cognición (es decir, niveles más bajos de pensamiento dialéctico ingenuo) se explican en realidad a través de los efectos beneficiosos del mindfulness en las relaciones personales (p. ej., mejores percepciones de la seguridad del apego adulto). El modelado de la ecuación estructural demostró que la seguridad del apego adulto de hecho medió completamente la relación negativa entre el pensamiento dialéctico ingenuo y el mindfulness. Estos resultados ponen de relieve una comprensión de la meditación del mindfulness como una práctica que no solo cultiva el afecto armonioso y la cognición, sino también las relaciones armoniosas con los demás.

Drawn from centuries-old Buddhist meditative practices, mindfulness represents a particular set of qualities of attention and awareness that can be cultivated and developed through meditation (Bear, 2003). Mindfulness has been described as “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment” (Kabat-Zinn, 2003, p. 145). As such, the construct of mindfulness incorporates both a cognitive-attentional component whereby one's conscious awareness is sustained to what is immediately occurring in the present moment (Brown & Ryan, 2003) as well as an affectionate, compassionate, intrapersonal quality within the attending, whereby one sustains a sense of open-hearted, friendly presence and interest (Bishop et al., 2004; Neff, Hsieh, & Dejitterat, 2005).

Mindfulness has been associated with several indicators of psychological health, such as enhanced quality of life (Grossman et al., 2010), greater self-esteem and empathy (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Dekeyser, Raes, Leijssen, Leysen, & Dewulf, 2008), and reduced negativity bias and maladaptive ruminative thinking (Heersen & Philippot, 2011; Kiken & Shook, 2011). These findings suggest that mindfulness helps people to be more open to, and capable of effectively coping with, a broad range of available context-relevant and self-relevant information in the present moment, including both positive and negative self-relevant feedback and emotions (Goetz, Spencer-Rodgers, & Peng, 2008). Mindfulness training is thought to enhance metacognitive awareness, which is the ability to re-perceive or decenter oneself from one's thoughts and emotions, and instead to view these experiences as temporal and passing mental events rather than as accurate or static representations of reality (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999; Keng, Smoski, & Robins, 2011). Although mindfulness has been effectively applied and adapted onto a Western mental health context, with previous studies confirming its relationship with various positive outcomes from the perspective of Western mental health, its original Eastern/Buddhist conceptualization viewed its practice against the psychological backdrop of reflecting on and contemplating key aspects of Buddhist teaching, which included themes relating to impermanence, nonself, and suffering (Keng et al., 2011). Thus, in addition to examining mindfulness alongside constructs such as self-esteem, negativity bias, and ruminative thinking, it may also be helpful to examine mindfulness alongside constructs more closely related to its original Eastern/Buddhist cultural context. To this end, the present study will examine the relationship of mindfulness and one particular aspect of cognition known as naïve dialecticalism—a way of thinking that stems from Buddhist teachings on impermanence and nonself.

Naïve dialecticalismNaïve dialecticalism refers to the tolerance of apparently contradictory or ambivalent beliefs, a cognitive tendency that tends to be more common in (though is not exclusive to) East Asian cultures (Peng & Nisbett, 1999). Dialectical thinking can be distilled into three core principles: the principle of contradiction holds that two opposing propositions may both be true; the principle of change proposes that the universe is in flux and is constantly changing; and the principle of holism accepts that all things are inter-related (Peng & Nisbett, 1999). Within this tradition, dialectically oriented individuals tend to exhibit greater emotional complexity—that is, they are more likely to exhibit the co-occurrence of both positive and negative affect (Spencer-Rodgers, Peng, & Wang, 2010). They also tend to see the nature of the world in such a way where traits like masculinity and femininity, strength and weakness, and good and bad concurrently exist in the same object or event, and that such duality be regarded as both normative and adaptive (Spencer-Rodgers, Boucher, Mori, Wang, & Peng, 2009). Of note, these scholars earlier observed that “Western dialectical thinking is fundamentally consistent with the laws of formal logic … in the sense that contradiction requires synthesis rather than acceptance [whereas] … naïve dialecticism does not regard contradiction as illogical and tends to accept the harmonious unity of opposites” (Peng, Spencer-Rodgers, & Nian, 2006, p. 256).There is empirical evidence indicating that individuals from collectivist cultures whose modal worldview highly values naïve dialecticalism tend to report lower levels of self-esteem and psychological well-being, even after statistically controlling for potentially confounding factors such as moderacy bias (i.e., the tendency to avoid extremes and to respond neutrally) and modesty (i.e., the tendency to present oneself in a more humble or modest light; Crocker, Major, & Steele, 1998; Diener, Suh, Smith, & Shao, 1995; Spencer-Rodgers & Peng, 2004). When applied to an individual's self-concept, naïve dialecticalism is associated with greater reported global self-concept inconsistency (Boucher, 2011; Choi & Choi, 2002; Hamamura, Heine, & Paulhus, 2008). Naive dialectical thinkers tend to refrain from discounting self-criticism (Heine & Lehman, 1997), report lower levels of optimism (Heine, Lehman, Markus, & Kitayama, 1999), and emphasize and elaborate more negative emotions (Shimmack, Oishi, & Diener, 2002). Overall, they expect and accept more negativity in their lives because they more readily accept the co-existence of the negative even in the good that they observe in the world around them; additionally, they recognize that events of success are interrelated with failure, and they embrace a view of reality that is constantly changing and in flux (Spencer-Rodgers & Peng, 2004). Given such an approach of relating to the world, individuals oriented toward naïve dialecticalism may find it particularly difficult to emotionally self-regulate during times of distress. For example, when such individuals receive unfair criticism from another, their ready acceptance of the co-existence of both the good and the negative in their self-concept may disarm potentially adaptive psychological defenses and lead them to more willingly accept and internalize these criticisms, regardless of their validity.

Mindfulness and Naïve dialecticalismWe propose that mindfulness meditation, as it was originally developed and practiced, can be understood in part as a means of helping individuals attain liberation from suffering by attenuating naïve dialectical thinking. As alluded to earlier, naïve dialecticalism is likely to be subjectively experienced as distressing, especially without a means to interpret and constructively frame its associated emotional complexity in a manner that achieves a reflective and integrative form of cognition. Consequently, by training oneself to focus attention exclusively and non-judgmentally on the present moment (i.e., to engage in mindful self-awareness), the multiple and potentially conflicting layers of one's emotional landscape (which may potentially give rise to excessive negativity, self-judgment, and maladaptive rumination) are brought to light and adaptively addressed. As such, the attentional and non-judgmental evaluative processes associated with mindfulness provide individuals oriented toward naïve dialecticalism with a means to approach and cope with the challenges that often accompany complex and seemingly incongruent emotional responses.

Although other mechanisms may also be in play, we hypothesize that one way mindfulness accomplishes this end is by assisting individuals to more readily integrate their emotional complexity by viewing their co-occurring emotions paradoxically. This approach was in fact adopted by Linehan (1993), who developed a therapy modality for borderline personality disorder (i.e., Dialectical Behavioral Therapy) based on finding “wisdom within contradictions” (p. 32). This more integrated form of dialecticalism modeled by Linehan (1993) that is facilitated by the practice of mindfulness may be differentiated from the unmitigated naïve dialecticalism noted in our literature review in that it does not stop at the mere endorsement of contradictory positions (e.g., “When I hear two sides of an argument, I often agree with both”), but additionally incorporates some level of integration or synthesis between these positions based on paradox (e.g., “When I hear two sides of an argument, I often agree with both because both perspectives may in fact be correct”). Thus, more mindful individuals would tend to engage in less naïve dialectical thinking (which tends to be associated with more negative outcomes) in favor of more integrated paradoxical thinking (which tends to be associated with more positive outcomes).

The relationship of mindfulness to naïve dialecticalism: the potential mediating role of adult attachment securityAs alluded to earlier, both researchers on mindfulness (e.g., Kiken & Shook, 2012) as well as proponents of therapy modalities that incorporate mindfulness-based skill building (e.g., Teasdale et al., 2000) typically conceptualize the stress reducing benefits of mindfulness primarily to its ability to modulate maladaptive cognitive or attentional patterns. However, in keeping with his interpersonal neurobiology perspective, Siegel (2012) highlights the relational qualities of mindful awareness, describing it as “an open stance toward oneself and others (italics added), emotional equanimity, and the ability to describe the inner world of the mind.” Given this view, we contend that, within the research literature, the relational qualities of mindfulness have been underappreciated in favor of its cognitive/attentional qualities. Moreover, it is possible that the beneficial effects of mindfulness on cognition (e.g., in the form of decreased naïve dialecticalism) are in fact potentially accounted for via the beneficial effects of mindfulness upon one's relational patterns—such as those related to one's attachment orientation.

Notably, a substantial and growing theoretical and empirical literature has established a strong relationship between mindfulness and a secure attachment orientation. Previous studies have not only reported that mindfulness and attachment security are positively correlated (Cordon & Finney, 2008; Walsh, Balint, Smolira, Fredericksen, & Madsen, 2009), but also indicated that the two constructs share similar outcomes such as lower stress reactivity, better mental and physical health, and improved behavioral self-regulation (Baer et al., 2008; Brown, Ryan, & Creswell, 2007; Koole, 2009; Ryan, Brown, & Creswell, 2007; Shaver, Lavy, Saron, & Mikulincer, 2007). Similarly, developmental research suggests that individuals who have experienced responsive and validating caregiving are more likely to be securely attached and are also more likely to demonstrate an enhanced capacity for mindfulness-related competencies such as reflective functioning, attentional control, and cognitive openness and flexibility (Allen & Fonagy, 2006; Fonagy & Target, 2005; Mikulincer, 1997). Furthermore, Bouchard et al. (2008) reported that people with greater clarity and complexity in their representations of mental states (of self or others) also tended to exhibit lower attachment insecurity.

To date, no studies have explicitly investigated the relationship between naïve dialecticalism and attachment security. However, empirical findings on attachment security suggest that it may be inversely related to correlates of naïve dialecticalism. For example, in contrast to the global self-concept inconsistency observed in individuals who endorse naïve dialecticalism (Boucher, 2011; Hamamura, Heine, & Paulhus, 2008), individuals who are securely attached experience fewer self-discrepancies while conversely, those who are insecurely attached show higher self-discrepancies (Mikulincer, 1995). Moreover, in contrast to naïve dialectical thinkers, even though securely attached individuals recognize and are open to both positive and negative self-attributes (Mikulincer, 1995), they demonstrate greater life satisfaction (Homan, 2014), elevated positive emotions such as joy and interest, and reduced rates of negative emotions such as guilt, contempt, and shame (Consedine & Magai, 2003).

Similar to Siegel's relational conception of mindful awareness, the experience of secure attachment relationships also represents the expression of a set of coherent and well-integrated cognitive representations (i.e., internal working models) of oneself and others. According to George, Kaplan, and Main (1985), adults classified as secure on the basis of their responses to the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) are free to evaluate and coherently report both their positive and negative childhood experiences with adult caregivers. Similarly, the most prominent self-report measure of adult attachment (i.e., Experiences in Close Relationships Scale; Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998) conceptualizes and assesses adult attachment in terms of two orthogonal dimensions (attachment anxiety, or pervasive fears of partner rejection and abandonment; and attachment avoidance, or chronic discomfort with intimacy and interpersonal dependence). Persons scoring highly on one, the other, or on both dimensions concurrently are considered insecurely attached, while persons with low scores on both dimensions are deemed to have a secure attachment orientation that enables them to both synthesize and satisfy the paradoxical human needs for both connectedness and separateness. By contrast, attachment anxiety would represent a failure to synthesize one's need for autonomy while maintaining connectedness, whereas attachment avoidance would represent a failure to synthesize one's need for connectedness while maintaining autonomy.

Citing evidence that internal working models (IWMs) of the self and other exist within a hierarchical nested structure, Mikulincer and Shaver (2004) proposed that “security-enhancing experiences with attachment figures increase a person's capacity for inner regulation and… is related to the development of specific (self) soothing routines” (pp. 184–185). In line with this view, we believe that favorable attachment related experiences with multiple figures (e.g., peers, intimate partners) help consolidate the formation of a coherent and well integrated hierarchical network of IWMs that further promotes the development of flexible cognitive and affect regulation processes, including those directly related to mindfulness such as greater tolerance for ambiguity and stronger endorsement of “self-transcendence” values (Mikulincer, 1997; Mikulincer et al., 2003). Moreover, the availability of these favorable, internalized security representations may be crucial to the achievement of adaptive and optimal forms of dialectical thinking. By contrast, insecure adult attachment orientations have been associated with more rigid, unstable, and ineffective self-regulatory processes (Foster, Kernis, & Goldman, 2007; Goodall, Trejnowska, & Darling, 2012; Lopez, 2001) and, as such, should contribute to less mature, and more distressing forms of cognition (i.e., higher levels of naïve dialecticism).

Study aims and hypothesesTo date, no studies have explored naïve dialecticalism alongside mindfulness and adult attachment security, nor have previous studies examined attachment security as a mediator that potentially accounts for the cognitive benefits of mindfulness. Accordingly, we pursued two specific aims in the present investigation. First, we sought to examine whether and how mindfulness, naïve dialectical thinking, and adult attachment security were interrelated. For reasons outlined previously, we hypothesized that both mindfulness and secure attachment would be negatively related to naïve dialecticalism. In line with previous research, we also expected that attachment security would be significantly and positively correlated with mindfulness. Last, we proposed and tested a model wherein the beneficial effects of mindfulness on cognition (in the form of lower levels of naïve dialectical thinking) were hypothesized to be mediated by the beneficial effects of mindfulness on one's relationships (in the form of enhanced secure attachment representations). If this meditational model were to be confirmed, it would provide preliminary evidence suggesting that mindfulness first and foremost cultivates secure and harmonious relationships (with oneself as well as others), and that these internalized relationship patterns in turn cultivate more harmonious patterns of cognition.

MethodParticipants and procedureThree hundred students from a large urban university located in the Southwestern United States participated in the study. The age of the participants ranged from 17 to 54 (M=22.11, SD=4.37). Reflecting the demographic characteristics of the research subject pool from which they were recruited, most participants were female (85.9%). No single racial group comprised a majority of the sample; the largest group consisted of participants who identified themselves as White or European American (28.6%), with several others identifying themselves as Asian or Pacific Islander (25.1%), Latino or Hispanic (24.0%), Black or African-American (16.3%), Middle Eastern (4.9%), and other (1.1%).

MeasuresAttachment securityThe Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised Questionnaire (ECR-R;Fraley, Waller, & Brennan, 2000). The ECR-R is a 36-item self-report assessment of adult attachment developed from item response theory. Two 18-item subscales represent two orthogonal dimensions, which are hypothesized to underlie the attachment construct: attachment-related anxiety and attachment-related avoidance. Items are rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A sample item that loads onto the attachment-related avoidance subscale reads, “I find it difficult to allow myself to depend on romantic partners.” Likewise, a sample item that loads onto the attachment-related anxiety subscale reads, “I often worry that my partner doesn’t really love me.” Following the re-keying of reverse-scored items, subscale scores are obtained by calculating the average of all 18 responses. Fraley et al. (2000) reported that the ECR-R demonstrated robust psychometric properties; in its initial validation study using a sample of undergraduate students, internal consistency for the two factors was excellent (α=.93 for attachment anxiety and α=.95 for attachment avoidance). Internal consistency for the two factors in the present study were estimated at .94 (anxiety) and .94 (avoidance).

Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA;Armsden & Greenberg, 1987). The IPPA is a 75-item self-report questionnaire that evaluates different measures of attachment quality between participants and their mother, father, and peers; only items assessing attachment quality between participants and peers were used in the present study. Items on the questionnaire load onto three factors: degree of mutual trust (10 items; e.g., “I trust my friends”), quality of communication (9 items; e.g., “My friends help me to talk about my difficulties.”), and prevalence of anger and alienation (6 items; e.g., “I get upset easily around my friends”). Items are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (Almost Never or Never True) to 5 (Almost Always or Always True). Following the reverse-scoring of alienation items, these three IPPA scale scores are summed up to create an overall peer attachment score, with higher scores indicating more favorable peer attachments. Reliability and construct validity of the IPPA are well established. In their initial scale validation study, Armsden and Greenberg (1987) reported that peer attachment scores demonstrated an internal consistency reliability of .92 and a three-week test-retest reliability of .86. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha for scores on the peer attachment subscale was estimated at .80.

Dialectical thinkingDialectical Self Scale (DSS;Spencer-Rodgers, Peng, Wang, & Hou, 2004). The DSS is a 32-item self-report measure contains the following three factor-analytically-derived subscales that respectively assesses important features of the broader construct of naïve dialecticalism: contradiction (13 items; e.g., “I sometimes believe two things that contradict each other”), cognitive change (11 items; e.g., “I prefer to compromise than to hold on to a set of beliefs”) and behavioral change (8 items; e.g., “The way I behave usually has more to do with immediate circumstances than with my personal preferences”). Items are rated on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), and ratings are summed to create a total DSS score, with higher scores indicating higher levels of naïve dialectical thinking. Due to low pattern loadings, one item was removed from the contradiction subscale (item 27) and the behavioral change subscale (item 3). DSS scores have demonstrated acceptable reliabilities in samples of American and Chinese college students (Cronbach's alpha scores ranged from .71 to .86; for current study, alpha scores were .61, .78, and .73 for the contradiction, cognitive change, and behavioral change subscales respectively) as well as convergent validity with DSS scores correlated with reported contradictions in self-construals and health beliefs (Hou, Zhu, & Peng, 2003; Spencer-Rodgers et al., 2004).

MindfulnessMindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS;Brown & Ryan, 2003). The MAAS is a unidimensional 15-item self-report measure of trait mindfulness, or the relative level of a person's attention to and awareness of what is occurring in the present. The scale focuses on the attentional components of mindfulness (what the authors considered to be foundational to the construct), rather than on other attributes such as acceptance and empathy (Brown & Ryan, 2003). Items are rated on a 6-point scale, ranging from 1 (almost always) to 6 (almost never). A sample (reverse-coded) item on the scale reads, “I find myself listening to someone with one ear, doing something else at the same time.” Following rekeying of reverse-coded items, ratings are summed to produce a total MAAS score, with higher scores indicating higher levels of mindful attention and awareness. In its initial validation studies, Brown and Ryan (2003) reported an internal consistency (alpha) of .82 and test-retest correlation of .81; for the current study, Cronbach alpha reliability was estimated at .89.

ResultsPreliminary analysesPrior to conducting statistical analysis, the data were carefully screened for obvious and careless response patterns (e.g., all answers marked as “3” on a 5-point Likert scale) as well as unusually low survey response times. In addition, the data were also screened for both univariate and multivariate outliers. In all, a total of 18 problematic cases were identified and removed through this process, resulting in a final sample of 282 participants. Afterward, the data were checked for violations of univariate normality. Histograms were generated for each measure of the study and were found to adequately conform to a normal distribution; in addition, skewness and kurtosis values were also calculated and no value was observed to surpass +1 or −1.

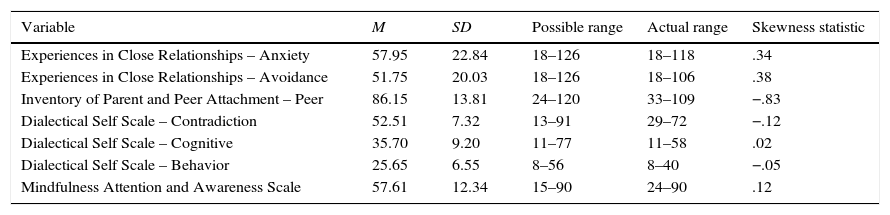

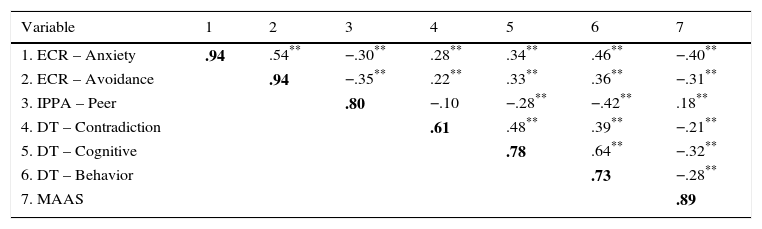

Descriptive statistics for all the measured variables are presented in Table 1. Intercorrelations among the measured variables are provided in Table 2. Correlations among indicators of mindfulness, secure adult attachment, and naïve dialecticalism were significant and in expected directions (rs=−.21 to −.32 between mindfulness and dialectical thinking; rs=.18 to .40 between mindfulness and secure attachment; and rs=−.10 to −.46 between secure attachment and dialectical thinking). In addition, moderate to large intercorrelations between the proposed indicators provided support for the formation of latent constructs from multiple indicators for attachment security (rs=.30–.54), and dialectical thinking (rs=.39–.64). The latent construct for mindfulness was formed from item parcels of the fifteen items of the MAAS. In light of Matsunaga's (2008) recommendation of a 3-parcel-per-factor strategy (which safeguards against potential estimation bias), three parcels were formed using the factorial algorithm (Rogers & Schmitt, 2004) or “single-factor” method (Landis, Beal, & Tesluk, 2000).

Descriptive statistics for the measured variables.

| Variable | M | SD | Possible range | Actual range | Skewness statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiences in Close Relationships – Anxiety | 57.95 | 22.84 | 18–126 | 18–118 | .34 |

| Experiences in Close Relationships – Avoidance | 51.75 | 20.03 | 18–126 | 18–106 | .38 |

| Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment – Peer | 86.15 | 13.81 | 24–120 | 33–109 | −.83 |

| Dialectical Self Scale – Contradiction | 52.51 | 7.32 | 13–91 | 29–72 | −.12 |

| Dialectical Self Scale – Cognitive | 35.70 | 9.20 | 11–77 | 11–58 | .02 |

| Dialectical Self Scale – Behavior | 25.65 | 6.55 | 8–56 | 8–40 | −.05 |

| Mindfulness Attention and Awareness Scale | 57.61 | 12.34 | 15–90 | 24–90 | .12 |

Correlations among the measured variables.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ECR – Anxiety | .94 | .54** | −.30** | .28** | .34** | .46** | −.40** |

| 2. ECR – Avoidance | .94 | −.35** | .22** | .33** | .36** | −.31** | |

| 3. IPPA – Peer | .80 | −.10 | −.28** | −.42** | .18** | ||

| 4. DT – Contradiction | .61 | .48** | .39** | −.21** | |||

| 5. DT – Cognitive | .78 | .64** | −.32** | ||||

| 6. DT – Behavior | .73 | −.28** | |||||

| 7. MAAS | .89 |

Note: The coefficients on the diagonal in bold are the Cronbach's alpha for each scale.

The software package, STATA (version 12.0), was used to estimate relations among the study variables, derive model fit, and to test the significance of the anticipated mediation effect of secure adult attachment representations on the relationship between mindfulness and naïve dialecticism. Following the recommendations of Schumacker and Lomax (2004), a variety of global fit indices were used to test the proposed model. These included the chi-square statistic, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; a value of less than .08 is considered an upper bound value that indicates adequate fit to the data), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; a value greater than 0.95 indicates adequate fit), and the Standardized Root-Mean Square Residual (SRMR; a value less than 0.05 indicates adequate fit).

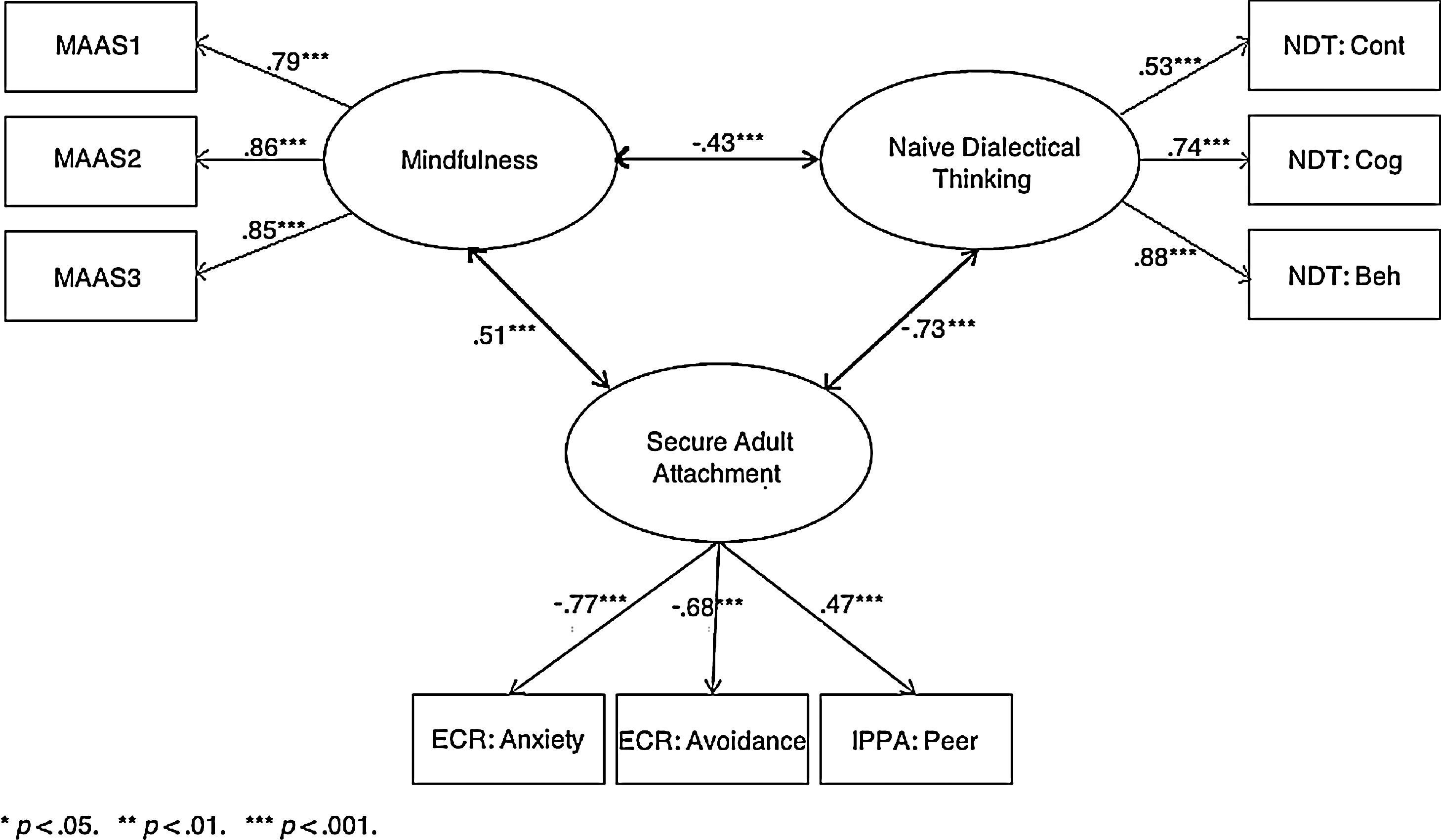

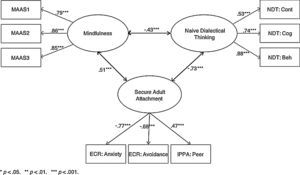

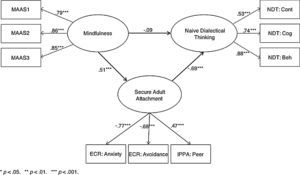

In accordance with Bollen's (1989) two-step rule and Anderson and Gerbing's (1988) two-step approach to modeling, a measurement model was specified and tested as a first step. The measurement model (see Fig. 1) consisted only of unidirectional paths between latent variables and their corresponding manifest indicators, with bidirectional correlations between the latent variables. This model produced significant factor loadings for all manifest variables on their respective latent constructs and demonstrated adequate fit to the data, χ2(24, N=282)=64.15, p<.001, CFI=.96, SRMR=.04, RMSEA=.08 (Lower CI=.06; Upper CI=.10).

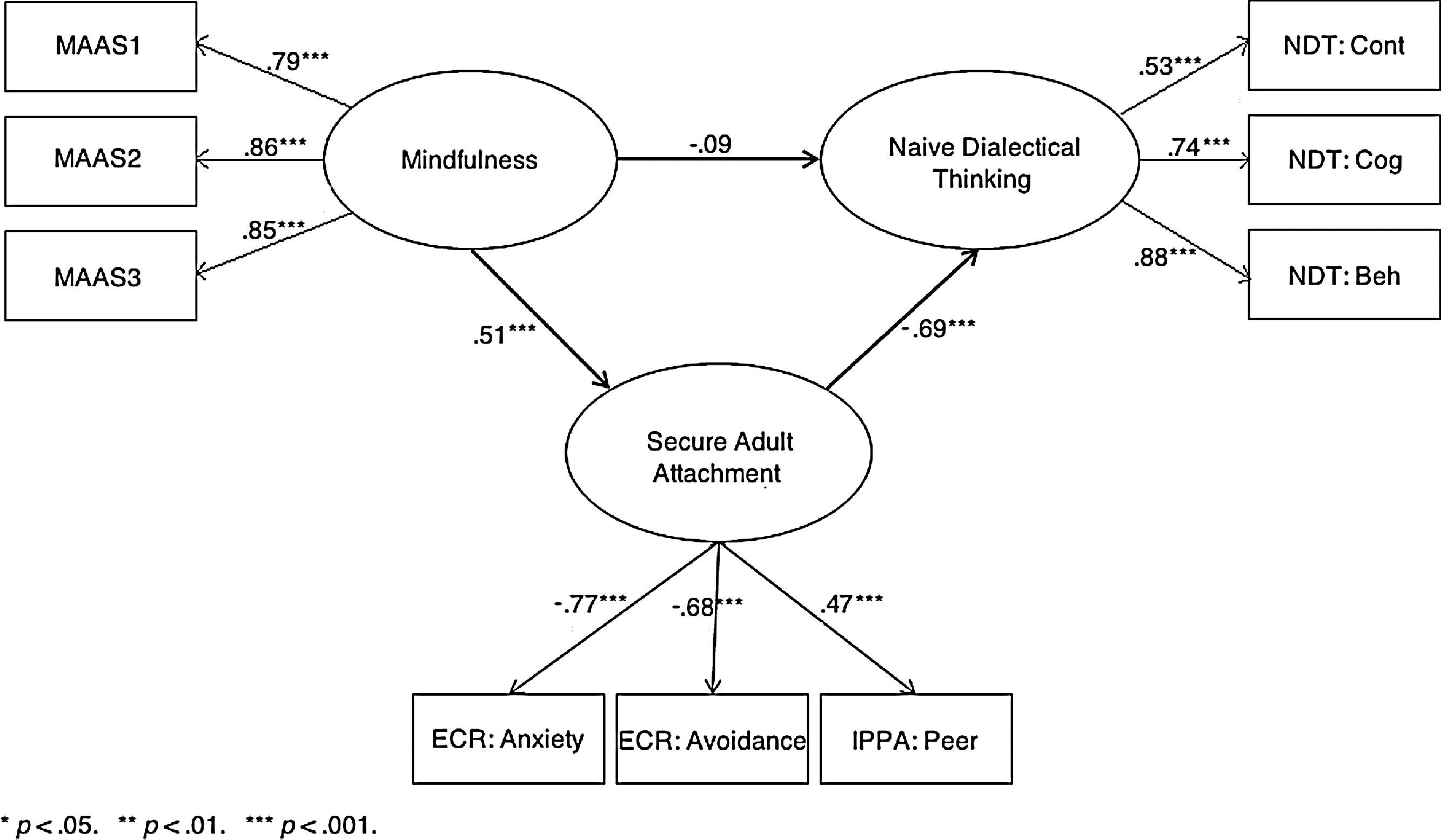

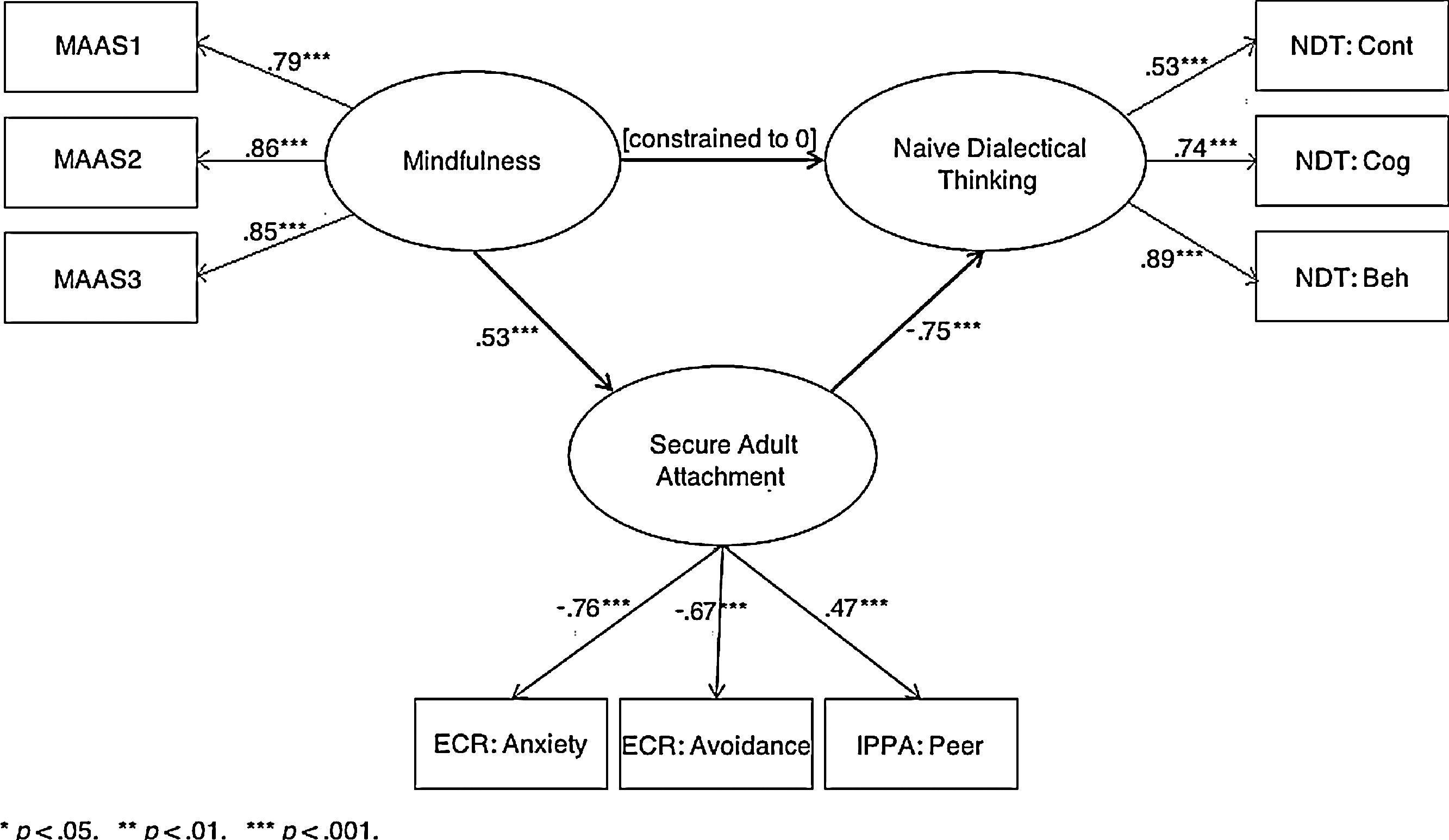

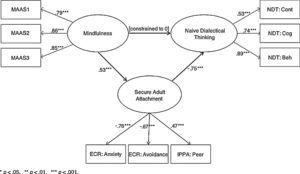

In light of the adequate fit statistics of the measurement model, model testing continued with an examination of the full structural model (see Fig. 2). The full model also provided adequate fit to the data, χ2(24, N=282)=64.15, p<.001, CFI=.96, SRMR=.04, RMSEA=.08 (Lower CI=.06; Upper CI=.10). Notably, the direct effect between the predictor (mindfulness) and criterion (naïve dialectical thinking) variables was no longer statistically significant (β=−.09, p=.264). Next, the full structural model was modified so that this direct effect from mindfulness to naïve dialectical thinking was constrained to zero (see Fig. 3). This constrained model also demonstrated adequate fit to the data, χ2(25, N=282)=65.36, p<.001, CFI=.96, SRMR=.04, RMSEA=.08 (Lower CI=.05; Upper CI=.10). The difference in chi-square values between the full and constrained models was not statistically significant (Δχ2=1.23, p>.05), indicating that the constrained model was a more parsimonious fit for the data.

The statistical significance of the proposed mediation effect was further tested using a procedure based on bootstrap methods (Mallinckrodt, Abraham, Wei, & Russell, 2006; Shrout & Bolger, 2002). However, before testing could begin, prerequisites for this procedure were first addressed. First, Baron and Kenny (1986) proposed that each pair of variables in the three-variable system must be significantly correlated before such a procedure can be conducted. To confirm that these prerequisite conditions are met, three separate structural models were tested (one containing only the mindfulness and naïve dialectical thinking latent variables, one with mindfulness and secure adult attachment, and one with secure adult attachment and naïve dialectical thinking). Results from the model with only the mindfulness and naïve dialectical thinking latent variables indicated that the mindfulness latent variable was significantly and negatively correlated with naïve dialectical thinking (r=−.44; p<.001). Continuing, the structural model with only the mindfulness and secure adult attachment latent variables indicated that mindfulness was significantly and positively correlated with secure adult attachment (r=.50; p<.001). Last, results from the model with only the secure adult attachment and naïve dialectical thinking latent variables indicated that secure adult attachment was significantly and negatively correlated with naïve dialectical thinking (r=−.74; p<.001).

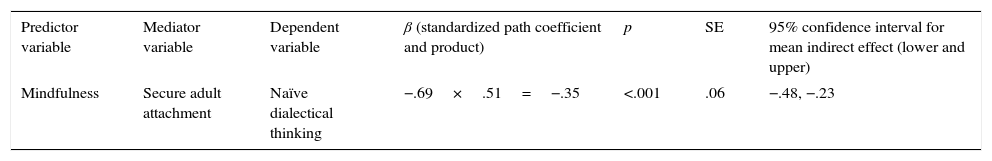

Moving forward with the procedure to test for the mediation effect, we created 1000 bootstrap samples from the original data for the hypothesized structural model using the bias-corrected percentile method to estimate the path coefficients. Point estimates of the magnitude of the indirect effect (i.e., the products of the path from the independent variable to the mediator and the path from the mediator to the dependent variable), together with the associated 95% confidence interval were also estimated through the same 1000 bootstrap samples. Accordingly, if the confidence interval excluded zero, then the indirect effect would be considered statistically significant at the .05 level (Mallinckrodt et al., 2006; Shrout & Bolger, 2002). Results from the bootstrap analyses for the structural model are shown in Table 3, which indicate that the bias-corrected confidence intervals for the indirect effect between mindfulness and naïve dialectical thinking (via secure adult attachment representations) did in fact exclude zero, thus confirming that the mediation effect was statistically significant (p<.001). In summary, these results support the notion that the relationship between mindfulness and naïve dialectical thinking was indeed mediated by secure adult attachment.

Bootstrap analysis of hypothesized structural model (naïve dialectical thinking—adult attachment insecurity—mindfulness), magnitude, and statistical significance of indirect effects.

| Predictor variable | Mediator variable | Dependent variable | β (standardized path coefficient and product) | p | SE | 95% confidence interval for mean indirect effect (lower and upper) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mindfulness | Secure adult attachment | Naïve dialectical thinking | −.69×.51=−.35 | <.001 | .06 | −.48, −.23 |

Note. N=282.

The present study examined interrelationships among three latent constructs: mindfulness, secure adult attachment, and naïve dialecticalism. Concerning the relationship between mindfulness and secure adult attachment, our findings replicated those of prior studies (e.g., Cordon & Finney, 2008; Walsh et al., 2009) which found that individuals who were securely attached also tended to exhibit a greater disposition toward mindfulness (or, conversely, that insecurely attached individuals tended to exhibit a weaker disposition toward mindfulness). Notably, in the present study, the variability accounted for within this relationship (i.e., between mindfulness and secure attachment) was noteworthy (R2=.25, p<.001).

Continuing, although little or no research had specifically examined the relationship between naïve dialectical thinking and either adult attachment security or mindfulness, we hypothesized that naïve dialecticism would be negatively correlated with both mindfulness as well as secure adult attachment. These hypotheses were supported through a series of latent variable structural equation models. Together, our findings are consistent with the notion that naive dialectical thinking may indeed be experienced and interpreted in a manner that is neither paradoxical nor nonjudgmental, potentially resulting in both problematic thinking patterns as well as problematic relational patterns. That is, rather than mindfully and non-judgmentally attending to the present (and often paradoxical) realities of others (e.g., that other people are dynamic and may therefore embody both positive as well as negative characteristics), the naïve dialectical thinker may be more prone to impose rigid and over-generalized interpretations on other people's motives and intentions, or to see others at times as either all good or all bad, depending on the context.

Another purpose of this study was to investigate whether the beneficial effects of mindfulness on cognition (in the form of decreased naïve dialectical thinking) may in fact be mediated by the beneficial effects of mindfulness on one's relationships (in the form of enhanced secure attachment). Results from our data analysis demonstrated that trait mindfulness was indeed indirectly related to naïve dialectical thinking through the mediation of secure adult attachment. In other words, these results suggest the possibility that people who are mindful tend engage in less naïve dialectical thinking in part because mindful people tend to report more securely attachments in their important adult relationships, which in turn inhibits naïve dialectical thinking. Said differently, mindfulness, first and foremost, cultivates harmonious relationships (with oneself as well as others), which then in turn is associated with harmonious cognition. This finding is consistent with Siegel's (2012) definition of mindful awareness as well as with the inference discussed earlier in this paper suggesting that a secure adult attachment orientation may have the potential to transform individuals’ raw experience of emotional complexity and global self-concept inconsistency in ways that mitigate distress, thereby enhancing their ability to be mindfully and non-judgmentally present to their immediate and unfolding experience.

Our findings have potential preliminary implications and considerations for the clinical practice of psychological science. As noted earlier, mindfulness-based interventions are typically understood within a cognitive-behavioral framework, in which mindfulness is believed to change behavior and reduce symptoms through the inhibition of avoidance, the modulation of problematic thought patterns such as splitting or all-or-nothing thinking, and the development of enhanced self-observation and self-management capacities (Baer, 2004; Teasdale et al., 2000). While such an understanding of mindfulness continues to hold true, the results of this study potentially highlight the construct of mindfulness as one that psychodynamically encompasses not only cognition and behavior but also, and perhaps more saliently, one's interpersonal dispositions. Additionally, this study presents initial evidence that some of the cognitive benefits derived from mindfulness are possibly accounted for by the beneficial impact of mindfulness on one's relationships.

Drawing from this initial finding, practitioners seeking to incorporate the practice of mindfulness into their clinical work may consider it as not only an intervention to aid clients to more effectively regulate their cognition and affect, but also a means of enhancing the security of their attachment relationships. For example, a therapist may choose to apply mindfulness practices within the context of couples therapy to enhance communication and recognition of mental states to one's partner. This is in line with the findings of Barnes, Brown, Krusemark, Campbell, and Rogge (2007) that higher mindfulness predicted higher relationship satisfaction within romantic relationships. Similarly, in their randomized wait-list control study, Carson et al. (2004) found significant increases in relationship satisfaction, autonomy, relatedness, and mutual acceptance, and significant decreases in relationship distress, among participants who completed a Mindfulness-Based Relationship Enhancement program.

Moreover, in line with Mikulincer and Shaver's (2004) nested model, the self-regulatory qualities of mindfulness may be understood as representing an expression of one's internal working models of the self and others. As such, clients whose presenting problems include difficulties relating to emotional complexity, incongruity, and dysregulation may benefit from relational interventions aimed at mitigating patterns of insecure attachment representations. As Mikulincer and Shaver (2004) assert, insecure attachment representations potentially hinder the development of mindfulness-based emotional self-regulatory competencies. If this is the case, it would follow that removing such hindrances may in fact enhance the effectiveness and retention of subsequent mindfulness skills-based interventions. In fact, preliminary clinical research supports this proposition; for example, Levy et al. (2006) confirmed that a psychodynamic treatment designed to enhance attachment security among patients with borderline personality disorder also demonstrated significant improvement in these patients’ emotional self-regulation when compared to a separate group of patients with borderline personality disorder who received Dialectical Behavior Therapy.

Citing both theoretical and empirical rationales, Shaver et al. (2007) suggested that the construct of mindfulness be placed within an attachment framework so that it might benefit from the extensive knowledge base that currently exists within the field of attachment. Findings from the present study lend credence to this proposition, suggesting that the cultivation of both the attentional and non-judgmental evaluative dimensions of mindfulness support secure and well-integrated cognitive representations of self and others (i.e., secure internal working models). In other words, it may be the case that securely attached individuals are more mindful because they relate to themselves and their significant others in similar ways (i.e., in an open, trusting, and self-reflective manner). Conversely, insecurely attached individuals are less mindful because they relate to themselves and to their significant others in a more rigid, distrusting, and reactionary manner. Future research is needed to confirm this possibility. Furthermore, future studies should further elucidate the relationship between secure attachment and mindfulness by empirically investigating specific mechanisms that are presumed to underlie their interconnectedness.

In conclusion, the findings of this study suggest that mindfulness, as it was originally developed and practiced in its native context, may be understood in part as a keenly contextually appropriate approach to help individuals attain greater liberation from suffering by decreasing naïve dialectical thinking, providing people with a means to approach (instead of avoid) and to cope with the challenges that can accompany the complex and seemingly incongruent emotional responses associated with naïve dialecticalism. In conjunction with the findings of previous research, our study findings highlight the salience of the positive relational impact of mindfulness (from both an intrapersonal and interpersonal perspective), thus affirming Siegel's (2012) conceptualization of mindfulness as a practice that cultivates harmonious relationships not only toward oneself, but toward others as well.

Several limitations to this study require consideration, many of which stem from its reliance on self-report measures to operationalize the constructs under investigation (which may contribute to common-method variance) as well as its cross-sectional and correlational design. Together, these characteristics limit the extent to which conclusions can be drawn concerning the interrelationships among attachment security, naïve dialectical thinking, and mindfulness. Furthermore, the gender imbalanced, university based, college aged sample may also limit the generalizability of the findings, especially for populations who are older, less educated, and with greater male representation. However, notably, the sample used in this study was racially/ethnically diverse, with over 70 percent of the sample representing racial and ethnic minority groups. Nevertheless, future studies should consider collecting data across multiple time points, along with gathering larger and more gender-balanced samples to permit multiple group comparisons of the tested models.