Moyamoya syndrome is an idiopathic syndrome characterised by progressive occlusion of the intracranial internal carotid arteries associated with the bilateral formation of a network of small vessels (moyamoya phenomena) which are situated around the stenotic area.1 This syndrome may be associated with sickle cell anaemia, neurofibromatosis type 1, brain radiation therapy, and Down syndrome.2 Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is an autosomal dominant disorder characterised by the appearance of café au lait spots, axillary freckles, cutaneous neurofibromas, Lisch nodules, skeletal dysplasia, and optic gliomas. When moyamoya syndrome is associated with NF1, its cerebrovascular symptoms usually appear in childhood.3

This case report describes a 47-year-old woman who smoked and had migraines. She had no family history of cerebrovascular illness or neurocutaneous syndromes. Personal cerebrovascular history: three years earlier the patient presented with right hemiparesis and mild aphasia secondary to ischaemic stroke of undetermined aetiology and affecting both basal ganglia and the left frontoparietal region. Extensive analyses including an echocardiogram and Doppler sonography of the supra-aortic trunks showed no significant alterations. The cerebral angiograph showed an occlusion in the right middle cerebral artery from segment M1 with collateral circulation through the meningeal branches and deep penetrating branches of the anterior cerebral artery. The M1 segment of the left middle cerebral artery showed a stenosis smaller than 1cm; similar stenoses were also present in 2 areas of the superior division of the M2 segment, which presented a beaded appearance. There was no evidence of a small vessel network in the stenotic area. We prescribed Aspirin® at a dose of 300mg/day and prednisone in decreasing doses concluding with a dose of 10mg/day. Upon discharge the patient continued to experience mild right hemiparesis and mild anomic aphasia.

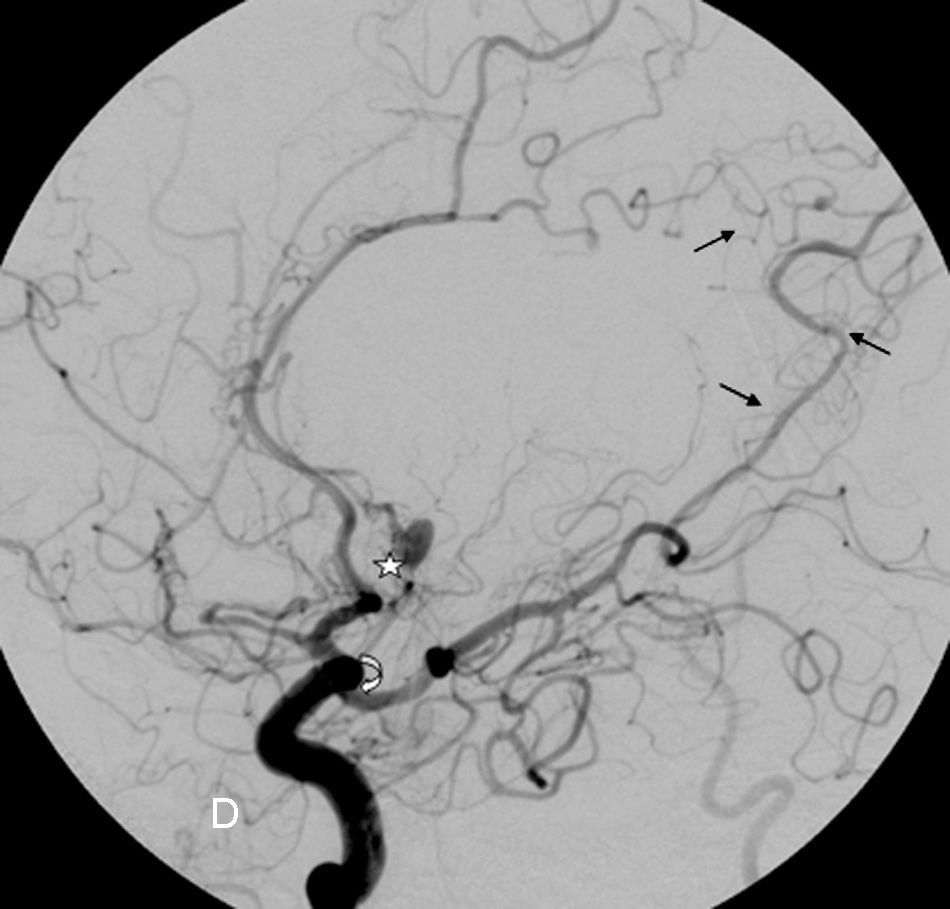

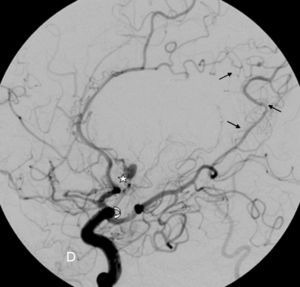

The patient was readmitted with sudden-onset headache and a decreased level of consciousness; a CT scan revealed a subarachnoid haemorrhage that was the most pronounced in the medial portion of both frontal lobes. An exhaustive physical examination revealed a number of café au lait spots on the abdomen and left thigh, axillary freckling, and cutaneous fibromas, which match the diagnostic criteria of NF1 (Table 1). The patient experienced seizures and obstructive hydrocephalus, but placing a ventriculoatrial shunt was ruled out. A cerebral angiograph (Fig. 1) showed arterial occlusions in both middle cerebral arteries with leptomeningeal collateral pathways through transdural anastomosis, which is typical of moyamoya disease, as is the existence of a pseudoaneurysm in segment A2 of the left anterior cerebral artery. Fifteen days after admission the patient worsened rapidly with subarachnoid rebleeding which led to death. The family did not consent to an autopsy.

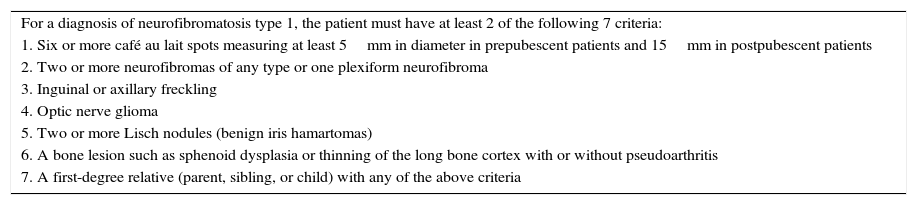

Diagnostic criteria for neurofibromatosis type 1.

| For a diagnosis of neurofibromatosis type 1, the patient must have at least 2 of the following 7 criteria: |

| 1. Six or more café au lait spots measuring at least 5mm in diameter in prepubescent patients and 15mm in postpubescent patients |

| 2. Two or more neurofibromas of any type or one plexiform neurofibroma |

| 3. Inguinal or axillary freckling |

| 4. Optic nerve glioma |

| 5. Two or more Lisch nodules (benign iris hamartomas) |

| 6. A bone lesion such as sphenoid dysplasia or thinning of the long bone cortex with or without pseudoarthritis |

| 7. A first-degree relative (parent, sibling, or child) with any of the above criteria |

Cerebral angiograph. Image of the right carotid area. Complete occlusion of the right middle cerebral artery at the origin of the carotid bifurcation, with stenosis of the supraclinoid carotid (curved arrow). The Sylvian fissure has been revascularised through the anterior and posterior cerebral arteries, as has the external carotid through the middle meningeal artery (transdural anastomosis: straight arrows). The aneurysm appears in segment A2 of the left anterior cerebral artery (star).

Moyamoya syndrome is diagnosed based on the following angiography findings: unilateral/bilateral stenosis or occlusion of the intracranial internal carotid artery or the proximal branches of the Circle of Willis in early stages; multiple small collateral lenticulostriate and thalamoperforating arteries that resemble a puff of smoke (‘moyamoya’ in Japanese) in the intermediate stage; and anastomosis through bone or dura between the internal and external carotid arteries in the late stages.4

In an extensive series of 70 patients with cerebral infarcts of unusual aetiology, only one patient presented moyamoya syndrome, which indicates how infrequent this diagnosis is, especially when associated with NF1.5 Our patient meets the diagnostic criteria for NF1.6 There may be no family history in cases of de novo mutations as was the case in our patient. Linkage studies have discovered that one of the genes associated with familial moyamoya is located in chromosome 17q25, which is not far from the NF1 gene situated at 17q11.2.7 This suggests the possibility of allelism of these 2 genes.8,9 Patients with unilateral findings are considered to have moyamoya syndrome even if the findings are not associated with other disorders.8 Forty percent of the patients who are initially only unilaterally affected will show a contralateral effect with time, according to longitudinal studies.10 The natural course of this syndrome varies. It may advance slowly, with rare intercurrent episodes, or it may be fulminant with rapid neurological decline.11 A study conducted in 2005 indicates that the incidence of progression is high even in asymptomatic patients, and that medical treatment (antiplatelet drugs, statins, antihypertensive drugs, and quitting smoking) does not slow disease progression.12

While ischaemic stroke is more likely to develop in children, subarachnoid haemorrhage is more likely to appear in adult patients.13 Intracranial haemorrhage typically affects adults with this syndrome. The location of the haemorrhage may be intraventricular, intraparenchymal (normally at the basal ganglia level), or subarachnoid. Subarachnoid bleeding has been attributed to the fragile collateral vessels that develop in conjunction with stenosis in the internal carotid. Changes in circulatory patterns in the base of the brain have been linked to the appearance of cerebral aneurysms which also contribute to the higher incidence of subarachnoid haemorrhage in these patients.13 Pathology studies have revealed that affected arteries do not show changes indicating atherosclerosis or vasculitis that could lead to occlusion,14 and that this occlusion is produced by smooth muscle cell hyperplasia together with intraluminal thrombosis.15

In conclusion, moyamoya disease should always be considered in young patients with bilateral ischaemic stroke. It can be confirmed with an angiograph showing stenosis of the intracranial carotid arteries along with development of multiple small collateral vessels around the stenotic area. The prognosis depends on whether the disease is diagnosed early and if surgical revascularisation is carried out. Lastly, patients with moyamoya must undergo a thorough cutaneous examination for dermatological signs typical of NF1.

Please cite this article as: Jiménez Caballero P. Síndrome de Moyamoya de aparición en la edad adulta en una paciente con neurofibromatosis tipo 1. Neurología. 2016;31:139–141.