Stroke is the sixth leading cause of disability in Spain. Patients may present motor, sensory, or cognitive sequelae, which can be minimised with early treatment. To this end, there is a need for quick-to-administer assessment tools to evaluate deficits in these areas. The Oxford Cognitive Screen (OCS) is a brief test specifically designed to assess cognitive function in patients with stroke. Our aim in this study is to report the linguistic and cultural adaptation of a Spanish-language version of the test (OCS-S).

MethodsThe linguistic validation was conducted with a process of double translation and 10 consensus meetings of the multidisciplinary research team. We also performed 3 pilot studies, with 5 potential users, 23 healthy individuals, and 23 patients with stroke (ischaemic in 61% of cases and haemorrhagic in 39%), respectively; participants were aged between 31 and 88 years.

ResultsThe OCS-S includes the 10 subtests, the coding of responses, and the scoring system from the original version. We modified and extended the instructions for administration in order to ensure the reliability of the content and its application. Five tasks were modified (images, numbers, and sentences) and the praxis subtest was modified to evaluate both hands. The pilot studies confirmed comprehension in the target population, independently of any cognitive problems.

ConclusionThe OCS-S is conceptually and linguistically equivalent to the original test, enabling psychometric assessment and application of the test in the Spanish population. The OCS-S may be a useful screening tool for quickly assessing cognitive function after stroke.

En España el ictus es la sexta causa de discapacidad. Sus secuelas producen alteraciones motoras, sensoriales y cognitivas, que pueden minimizarse con una actuación terapéutica temprana. Por ello se necesitan instrumentos de evaluación rápida que detecten déficits en estas áreas. El Oxford Cognitive Screen Test (OCS) es un test breve diseñado para la valoración de funciones cognitivas en pacientes con ictus. Nuestro objetivo fue generar una versión española (OCS-E) realizando una adaptación lingüística y cultural.

Material y métodosDiseño de validación lingüística con doble traducción y 10 reuniones de consenso del equipo investigador multidisciplinar. Tres estudios piloto administrando el test respectivamente a 5 usuarios potenciales, 23 personas sanas y 23 diagnosticadas de ictus isquémico (61%) o hemorrágico, con edades entre 31-88 años.

ResultadosEl OCS-E mantiene las 10 tareas originales, la codificación de respuestas y el sistema de puntuación. Se modificaron y ampliaron las instrucciones de administración, lo que asegura la fiabilidad del contenido y de su aplicación. En 5 tareas se han modificado imágenes, números y frases. La tarea praxia se amplió para evaluar ambos miembros superiores. Los estudios piloto confirmaron que las personas de la población diana comprendían de forma adecuada las tareas, con independencia de la existencia de problemas cognitivos.

ConclusionesLa adaptación cultural ha generado una versión lingüística y conceptualmente equivalente, permitiendo su estudio psicométrico y posterior aplicación en población española. El OCS-E puede ser un instrumento de cribado útil para evaluación rápida de funciones cognitivas postictus.

Stroke has a considerable impact on society and healthcare systems, and is the second leading cause of death worldwide. In 2016, a total of 5.78 million people died due to stroke.1 Its incidence varies between countries, and ranges from 41 cases per 100 000 population in Nigeria to 316 cases per 100 000 population in Tanzania.2,3 In Spain, stroke is the sixth leading cause of disability.4

By 6 months after stroke, 26.1% of all patients die, and 32.4% are dependent; overall, 44% of the surviving patients are estimated to be functionally dependent.5 This involves very high social and healthcare costs, with stroke accounting for approximately 3%-4% of the overall healthcare expenditure.6 Between 40% and 60% of patients with some impairment or disability after stroke are eligible for rehabilitation programmes.5

Early motor rehabilitation therapy after stroke is considered useful because it minimises the harmful effects of inactivity and promotes neuroplasticity mechanisms after the vascular lesion, as well as the patient’s adaptation to the impairment, among other benefits. Therefore, patient mobilisation is recommended as soon as clinical status so permits,7,8 the timing and intensity of treatment onset remain controversial.9–12

Early identification of other impairments derived from the vascular lesion, such as visual and language alterations, is important for providing patients with compensatory strategies to improve their functional status.13–15

Rehabilitation treatment must be comprehensive, managing all of the patient’s symptoms (motor, sensory, visual, coordination, communication, swallowing, and cognitive/behavioural alterations). It should include physiotherapy and occupational therapy and, when applicable, speech therapy and/or neuropsychological (cognitive/behavioural) therapy.16 The rehabilitation of praxis alterations in patients with left-hemisphere stroke has shown benefits in recovering the ability to perform activities of daily living,7 as well as in developing compensatory strategies for memory impairments.17 Therefore, it is essential to have tools for rapid, accurate detection of cognitive impairment in patients with stroke.

In Spain, no specifically-designed tools are available for cognitive assessment of patients with stroke. Such screening scales as the Mini–Mental State Examination,18,19 the clock-drawing test,20 and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment21 are frequently used in clinical practice. All these scales measure cognitive impairment in different areas,22 but were developed to assess cognitive deficits in other diseases, especially in dementia.

The Oxford Cognitive Screen (OCS) is a test specifically designed to quickly assess cognitive alterations in patients with stroke.23 Its main advantage is that it can be used to assess patients with expressive aphasia and spatial neglect. Furthermore, with the aim of controlling for the impact of motor deficit in the upper limbs, which is common after stroke, all the tasks in the test can be performed with one hand.

The aim of this study is to develop a cultural adaptation of the OCS to the Spanish population, creating a Spanish-language version conceptually equivalent to the original, as part of a complete validation study in the Spanish setting.24

Material and methodsDesign and procedureWe obtained the authorisation of the author of OCS, Glyn Humphreys Watts of Oxford University’s Department of Experimental Psychology and Isis Innovation Ltd. Our study was approved by the research ethics committee of Hospital Clínico Universitario San Juan de Alicante, Spain (reference: 158/317). All patients signed informed consent forms.

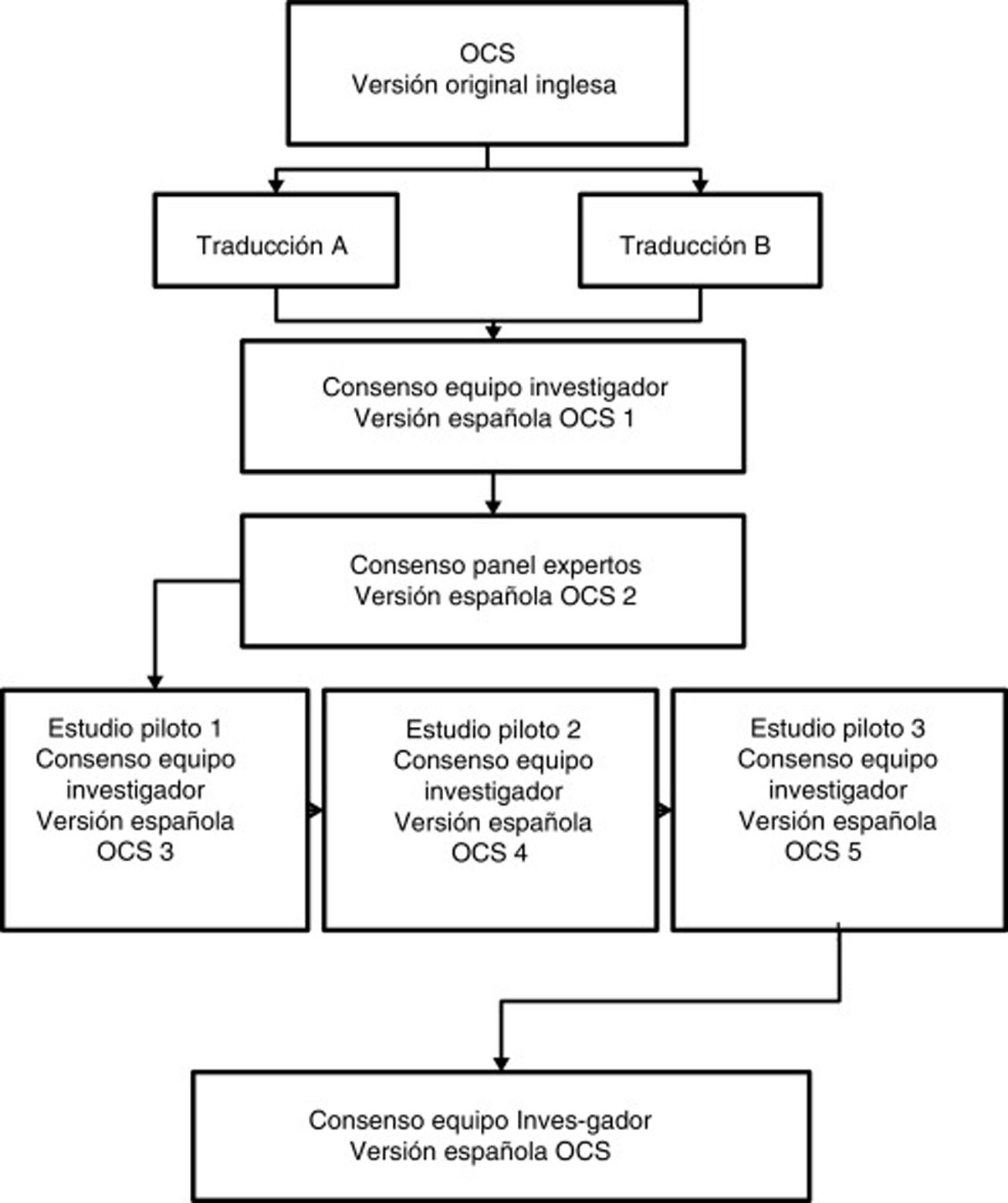

We designed a 2-stage linguistic validation (Fig. 1) according to the principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes.25

Stage 1. We included a forward translation design with 2 independent translations of the original scale by 2 Spanish-native translators. An iterative process for refinement was performed, working simultaneously with all the materials of each assessed item. Translations were compared against the original version, which involved several consultations with the authors; some items were tested in healthy individuals. As a result, we obtained a version suitable for the next stage.

Stage 2. We conducted 3 sequential pilot studies, with examiners and participants with different characteristics. The results led to the incorporation of successive changes until the final version was achieved (Fig. 1).

Versions A and B of the participant booklet were used indifferently. Each trial led to the generation of alternatives to the instructions and test content that were tested to select the most understandable and culturally adapted options.

ParticipantsPilot study 1. The test was applied by individuals with similar characteristics to those of future examiners (professionals from collaborating hospitals and health science students) (n = 5). The test was applied to members of the research group, who recorded any issues.

Pilot study 2. The test was administered to healthy individuals (n = 23) and to companions or relatives of patients with stroke, who presented similar sociodemographic characteristics to those of the target population but excluding participants with a history of dementia, stroke, or transient ischaemic attack. Participants’ ages ranged from 31 to 88 years. In terms of education, 75% had primary studies and the remaining participants could read and write.

The examiners were members of the research team, and recorded issues with administration and scoring.

Pilot study 3. The test was administered to 23 individuals (5 women and 18 men) who had presented ischaemic (61%) or haemorrhagic stroke (39%); progression time was classified as between 2 weeks and 6 months (78.3%) or between 6 months and one year (21.7%). Mean age was 60.5 years (range: 32-84; median: 65; 34.8% aged < 50 years; 43.5% aged 50-60 years; 21.7% aged > 70 years). Of all participants, 52.2% had primary studies, 21.7% university studies, 13% secondary studies, and 8.7% could read and write or were illiterate.

Participants in pilot studies 2 and 3 were recruited in the province of Alicante, from Hospital La Pedrera in Denia, Hopital Clínico Universitario San Juan de Alicante, Hospital Vega Baja in Orihuela, Hospital San Vicente del Raspeig, and Hospital Casaverde Alicante.

The Oxford Cognitive ScreenThe OCS assesses 5 cognitive domains: attention and executive function, language, memory, number processing, and praxis. It was designed based on a more extensive original version,26 and is quick to administer, taking approximately 10-25 minutes.

It includes 10 tasks: picture naming, semantics, orientation, visual field test, sentence reading, number writing, calculation, attention, praxis, delayed recall and recognition, and executive function (Table 1). The tasks are designed to assess patients with expressive aphasia and spatial neglect, both allocentric and egocentric. They include high-frequency short words, a multimodal presentation of the tasks and responses, and a central alignment of the items (reducing the need for visual tracking), which helps to focus attention.

Oxford Cognitive Screen items.

| Item | Task | Cognitive domain |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Picture naming | Visual and verbal naming: 4 pictures are shown separately. The patient is asked to name what is shown. | Expressive language |

| 2. Semantics | 4 pictures are shown simultaneously (aligned vertically). The patient is asked to point to the picture belonging to the category named. | This item screens for auditory comprehension of language (integrity of auditory analysis processes, deficits in auditory word recognition, and failure in the connection between auditory word recognition and the semantic system), by requiring the patient to follow a simple instruction and point an image. |

| 3. Orientation | Open-ended question with free answers on location, time of day, month, and year. | Time and space orientation |

| Multiple answers are available if the patient is unable to answer (for example, due to expressive aphasia, error, or not knowing the answer). | Contributes to the overall assessment of memory | |

| 4. Visual field test | Simple confrontation test in each quadrant of the visual field | Visual field deficit |

| Includes a reminder to assess the remaining tests in the intact visual hemifield | ||

| 5. Sentence reading | A 15-word sentence is presented in 4 lines, centrally aligned. The patient is asked to read it out loud. | Overall language assessment: discriminates between neglect dyslexia (attention processes) and surface dyslexia (lexical/semantic processes). Contributes to the assessment of recall and recognition |

| 6. Number tasks | a) The examiner says 3 numbers and the participant is asked to write down the numerals; b) 4 simple calculation tasks (2 additions and 2 subtractions). Multiple answers are available if the patient is not able to write (for example, due to expressive dysphasia). | Overall assessment of calculation ability |

| a) Writing | ||

| b) Calculation | ||

| 7. Attention | The patient is asked to cross out complete figures (hearts) on a sheet with 50 complete and incomplete figures. | Overall attention assessment: reflects the functioning of sustained and selective attention. Identifies allocentric and object neglect and egocentric or spatial neglect |

| 8. Praxis | Two mirror tasks consisting of mimicking meaningless hand movements performed by the examiner | Assessment of a coordinated movement system based on results or intention |

| 9. Delayed recall and recognition | a) Patients are asked to remember any of the 4 keywords from task 5. Multiple answer options. b) 4 questions in which the patient is asked to remember tasks performed previously (items 2, 5, 6, 7) | Overall assessment of memory |

| a) Verbal | ||

| b) Episodic | ||

| 10. Executive task: change of task | Three tasks consisting of drawing lines between increasingly complex geometrical figures | Ability to re-establish simple and complex sequences |

The OCS includes a set of materials: 1) an examiner’s manual, with detailed information on how to administer the test, instructions for the patient, and scoring procedure; 2) a test booklet containing the materials for administering the test; 3) a patient pack including the tasks to be completed by the patient (it contains 2 versions, which facilitates patient reassessment in a short period of time, avoiding the practice effect); and 4) an examiner’s sheet to record answers and scores for each task.

The original materials and the administration procedure are available from: https://innovation.ox.ac.uk/outcome-measures/the-oxford-cognitive-screen-ocs/

The access licence for the Spanish-language version is available from: https://process.innovation.ox.ac.uk/clinical

Instruments for the pilot studyData collection: recording of information on sociodemographic and clinical data (diagnosis, history, date, type and progression of stroke, presence of hemiparesis/hemiplegia or aphasia, and dominant hand).

Record of administration and scoring issues: administration, instruction, and scoring errors observed in each area of the test, doubts and difficulties perceived by the examiner, both in the examiner’s manual or in the examiner’s sheet, and suggested alternatives. It included a section with open-ended questions for cognitive analysis (for participants to explain in their own words the task, what they believed they are being asked about, etc), with instructions to ask the participant to think aloud (asking participants to express aloud what they are thinking while they perform a task).

ResultsStage 1Most of the work in this stage focused on the examiner’s manual. The introduction included 2 paragraphs, one detailing the documents and how to use them and another with general instructions to be provided before administering the test. We made changes in each area of the content: explanations of the main aim of the tasks, how to administer the scale (instructions for administration), instructions to be provided to the patient (examiner’s manual), scoring instructions, and the page number for each task in the patient pack. This ensures that all participants receive the same instructions and that the same procedure is followed to guide each task and result analysis.

We also changed the verbal and numerical content of the remaining documents (test booklet and patient pack) and improved the instructions on the examiner’s sheet (Table 2).

Results: modifications made in each study stage.

| OCS items | Stage 1 | Stage 2. Pilot study |

|---|---|---|

| Participants: (1) examiners, (2) healthy individuals, (3) patients | ||

| 1. Picture naming | Examiners accept synonyms of archivador (file cabinet): cajonera (chest of drawers); sandía (watermelon): melón (melon). | (2) Failures in recognising the picture of the hippopotamus: this was changed for a pig, and the picture of the watermelon was improved to avoid confusion with a wheel of cheese. (3) Examiners accept synonyms for zanahoria (carrot): chirivía (parsnip) and others; and for archivador (file cabinet): mesita con cajones (chest of drawers) and others. |

| 2. Semantics | ||

| 3. Orientation | All the possible local cities are specified in the answers. | (2) Cultural adaptation in the translation of times of day: mediodía (midday) accepted rather than mañana (morning) or tarde (afternoon), provided that the timeframe is adequate. |

| We added “town” or “village” to “city” in the question about location. | ||

| 4. Visual field test | (1) We specified the distance between examiner and participant and the distance between hands, to standardise the assessment of the visual field. | |

| (2) We changed the instructions for following the movements, replacing “hands” with “fingers.” | ||

| 5. Sentence reading | Word selection for neglect dyslexia: | (1) Examiner’s sheet: we added the acronym of each type of dyslexia to facilitate recording incorrect words in a corresponding space. |

| Version A (A): soldados, enseña, galeóna | (2) As an instruction to the participant, we added: “Please try to remember this sentence, as I will ask you to repeat it later” in order to facilitate task 9. | |

| Version B (B): hermanos, dirigente,aconformó, monótonob | In version A, enseña was replaced with contraseña. | |

| - With irregular syllable structure: (A): Coronel (colonel) | In version B, alternative sentences were designed to be tested in the next study. | |

| Word selection for surface dyslexia: | (3) In version B, we changed the sentence by deleting maître and croissant and introducing hamburguesa, queso, words with ambiguous spelling and accentuation, to assess surface dyslexia. | |

| - Foreign expressions: | ||

| (A): pizza, vermouth; (B): sandwich, maître, croissant | ||

| - Ambiguous spelling and accentuation: | ||

| (A): siguió, galeóna | ||

| - Low frequency and ambiguous spelling: | ||

| (B): dirigentea | ||

| 6. Number tasks | We added 2 further numbers to be tested in the next stage, 87 and 1300, in addition to the original numbers 708, 15200, and 400, to analyse cultural adaptation. | (2) We specified the possibility of using a piece of paper and pencil for calculations. |

| a) Writing | The task is introduced to the participant as follows: “I am going to ask you to do some sums and subtractions.” | |

| b) Calculation | ||

| 7. Attention | We introduced an explanation of allocentric neglect, which was not included in the original version, and modifications to clarify scoring: specifications for overall scoring and block calculation, left/right, for each type of neglect. | (1) In the examiner’s manual, we added the explanatory sentence “differentiating complete hearts and hearts with gaps in the left side or gaps in the right side”; changes in order (1st object asymmetry, 2nd space asymmetry); clarification on which blocks should be summed and subtracted, in accordance with the patient pack. |

| OCS items | Stage 1 | Stage 2. Pilot study |

| Participants: (1) examiners, (2) healthy individuals, (3) patients | ||

| 8. Praxis | We added exploration with both hands, rather than exclusively with the non-paretic hand. To clarify the performance and minimise mistakes, we expanded the examiner’s manual to include observing the pictures in the examiner’s sheet, and we duplicated recording of data and hand used in the patient pack. | (1) In the test, we specified each scoring possibility: correct, 1 mistake, > 1 mistake, task not completed, repeat mistake. |

| (2) At the beginning of each task, we included an explanatory sentence and a sentence to clarify to examiners that the same instruction may be performed with both hands. Change in the instruction: “… Please imitate exactly what I am doing, like a reflection in a mirror.” | ||

| (3) We specified “right hand” and “left hand” in each examiner’s sheet and improved the instructions. | ||

| 9. Recall and recognition | a) Instructions were clarified. We changed the sentence to be remembered (the same as in item 5). We underlined the keywords to be recalled. | (1) b) All the questions to be asked were included in the instructions. |

| a) Verbal | (3) b) Questions 1 and 2: the pictures of the cow and the hammer were replaced by pictures of a lion and a guitar to avoid confusion, | |

| b) Episodic | Question 3: we replaced the task “counting fingers” with the task “crossing fingers” as some patients need to use their fingers in calculation tasks. | |

| Question 4: we changed “what did you write before?” by “what did you do before?” as some patients did not need to write down calculations. We added a more detailed description in the answers: “Read poems, do sums, write down words, and do multiplications.” | ||

| 10. Executive task: change of task | We homogenised and ordered the instructions (for example, practice and task) for each of the 3 tasks. We modified the structure and order of the data in the examiner’s sheet. The pages of the test booklet were ordered in the order of execution. | (2) At the end of the instructions for each task, we added: “connect the circles, going from the biggest to the smallest, without going back.” |

| (3) We removed the recording of the time used in the test to adjust it to the latest version of the original. |

In the case of item 5 (sentence reading), in order not to distort the aim of the task, we changed the 4 critical irregular words (islands, quay, colonel, and yacht), whose Spanish translation does not allow for identification of the 2 types of dyslexia. We selected keywords with discriminatory ability (due to similarity, phonetic complexity, and spelling of the linguistic units), by consulting standardised Spanish-language tests for the assessment of dyslexia.27–29 The new sentence included 7 instead of 4 keywords: 3 to identify neglect dyslexia, 3 for surface dyslexia, and one for both. These words are represented with 4 indicators, as in the original version, but without modifying the total number of words in the sentence (n = 15). For neglect dyslexia, we introduced words sharing final letter sequences with other terms and words with irregular syllable structure. For surface dyslexia, we included irregular words (mostly anglicisms) or low-frequency words with ambiguous spelling and accentuation requiring the lexical pathway for correct pronunciation (Table 2).

Items 5 and 7-10 were subject to consultation with the authors, and we expanded the explanatory texts of the instructions for administration and scoring and improved the formatting and specifications in the examiner’s sheet. In general, texts in the participant pack were adapted through simplification to ensure that they were understood by individuals from the target population with any level of education (for example, “I am going to ask you to do some sums and subtractions” instead of “…calculation tasks”). After reviewing the translations, semantic and idiomatic changes, and confirming the experience and conceptual equivalence, we obtained an initial Spanish-language version, including versions A and B of the test (Table 2).

Stage 2As most of the content of the test is included in the examiner’s manual, the first pilot study enabled the final confirmation that the instructions, rules, methods, and scoring guidelines were understood by the potential administrators of the test. We made isolated changes to expression and added content to clarify the instructions for more complex tasks. We included the numbering corresponding to the test booklet in the examiner’s sheet and added more detailed instructions for completing the graphic summary of test results (Table 2).

In pilot studies 2 and 3, we were able to clarify doubts, improve expressions, and change terms that were conceptually unclear or unfamiliar to the participants. As a result of this procedure, we included such details in the instructions as reminding participants to use their glasses or hearing aids, if necessary. Cognitive analysis strategies also enabled us to confirm that all the assessed participants, regardless of the presence of cognitive impairments, correctly understood the tasks (Table 2).

DiscussionThe OCS is a brief test designed to assess cognitive alterations in patients with stroke. This study aimed to obtain a Spanish-language version of the OCS culturally adapted to our target population, ensuring its linguistic and conceptual equivalence.

The final Spanish-language version is equivalent to the original in terms of numbers, types of tasks, coding of answers, and scoring system. We improved the order and content of the instructions, achieving the aim that any examiner will apply the tasks in the same way and in the same order. In both versions, we modified pictures, numbers, and sentences, paying special attention to the specific objectives of the assessed area and the degree of difficulty required in the task. In the case of the praxis task, we expanded the assessment to both arms, ensuring the assessment of both the healthy and the affected side.

Linguistic differences between the original language and Spanish required meticulous work to maintain the assessment of dyslexia, especially surface dyslexia, whose impact on reading requires a more precise search for valid indicators. The fact that the main indicators of surface dyslexia are errors in irregular words and in regularisation makes it difficult to identify and discriminate this alteration in such a transparent language as Spanish, which practically lacks irregular words. Therefore, to overcome these difficulties in adapting the reading task, in addition to regularisation, we mainly used words with irregular or ambiguous spelling as possible indicators to detect alterations to the lexical pathway.

Furthermore, the results of our pilot studies enabled us to confirm its applicability and apparent validity, both in patients and in healthy volunteers. As a result of these procedures, there is no exact coincidence with the original version; however, these results are a desirable consequence in a cultural adaptation study, which requires conceptual equivalence to be maintained while adjusting the cultural context to the target population.30 Despite the differences, the application of the Spanish-language version of the OCS obtains comparable results both within and outside our setting.

Like other cognitive screening tests, the OCS presents certain limitations related to the clinical characteristics of the target population. For example, the daily changes occurring during the first weeks, fluctuations in the level of consciousness or attention, and the psychological impact of stroke may interfere with test results. Furthermore, some patients with stroke cannot undertake such tasks as sentence reading or number writing because they are unable to read or write. Likewise, the presence of dysphasia, dysarthria, or weakness of the dominant hand, among other impairments, may also impede the performance of some tasks. During the adaptation process, changes were made to avoid low level of schooling interfering in the understanding of tasks or in the possible correct answers. In any case, in clinical practice, the patient’s sociodemographic characteristics, diagnosis of stroke, presence of sensory deficits, and the results in the remaining items may provide some guidance on the relevance of mistakes in each item, or the significance of having to resort to multimodal answers in some items. From this perspective, the OCS does not provide exhaustive information, but is useful as a screening test to guide a subsequent comprehensive assessment.

In conclusion, through this study and by using qualitative methods, we have obtained a functionally equivalent Spanish-language version of the OCS, which met the prerequisite to undergo a psychometric study. This process, together with the results subsequently obtained in the validation study,21 enables us to ensure that the contributions and changes made have resulted in a sociocultural adaptation of the OCS as a screening test to assess the different cognitive functions after a stroke, which may be routinely used by Spanish-speaking physicians. We hope that it will contribute to more efficient and accurate diagnosis and early therapeutic intervention, which could prevent or delay development of cognitive impairment, and reduce the high personal, family, and social costs of stroke.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors would like to thank the following individuals and institutions for their scientific and logistical contribution to the project: the occupational therapists Tania Corbí Perez and Inmaculada Font García; Daniel Tornero Jiménez (head of the rehabilitation department at Hospital Universitario San Juan de Alicante); Santiago Mola Caballero de Rodas (head of the neurology department at Hospital Vega Baja in Orihuela); Jaume Morera Guitart (medical director at Hospital La Pedrera in Denia); Vladimir Herrero Tarruella (medical director at Hospital San Vicente del Raspeig, Alicante); Nele Demeyere, Ellie Slavkova, and Glyn Humphreys (from the Experimental Neuropsychology Department at Oxford University); and the Pathology and Surgery Department at Universidad Miguel Hernández, Elche (Spain).

We would also like to thank the following researchers for their collaboration to the project: Gema Mas Sesé (neurologist at the brain injury unit, Hospital La Pedrera, Denia); María Pérez Pomares (physiatrist at the brain injury unit, Hospital La Pedrera, Denia); Belén Piñol Ferrer (neuropsychologist at the brain injury unit, Hospital San Vicente del Raspeig, Alicante); and Ester Tormo Micó and Sara Cholbi Tomás (neuropsychologists at the brain injury unit, Hospital La Pedrera, Denia).

Please cite this article as: García-Manzanares MD, Sánchez-Pérez A, Alfaro-Sáez A, Limiñana-Gras RM, Sunyer-Catllà M, López-Roig S. Adaptación lingüística y cultural del Oxford Cognitive Screen (OCS) en población española. Neurología. 2022;37:748–756.