We conducted a descriptive study of symptomatic epilepsy by age at onset in a cohort of patients who were followed up at a neuropaediatric department of a reference hospital over a 3-year period.

Patients and methodsWe included all children with epilepsy who were followed up from January 1, 2008 to December 31, 2010.

ResultsOf the 4595 children seen during the study period, 605 (13.17%) were diagnosed with epilepsy; 277 (45.79%) of these had symptomatic epilepsy. Symptomatic epilepsy accounted for 67.72% and 61.39% of all epilepsies starting before one year of age, or between the ages of one and 3, respectively. The aetiologies of symptomatic epilepsy in our sample were: prenatal encephalopathies (24.46% of all epileptic patients), perinatal encephalopathies (9.26%), post-natal encephalopathies (3.14%), metabolic and degenerative encephalopathies (1.98%), mesial temporal sclerosis (1.32%), neurocutaneous syndromes (2.64%), vascular malformations (0.17%), cavernomas (0.17%), and intracranial tumours (2.48%). In some aetiologies, seizures begin before the age of one; these include Down syndrome, genetic lissencephaly, congenital cytomegalovirus infection, hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy, metabolic encephalopathies, and tuberous sclerosis.

ConclusionsThe lack of a universally accepted classification of epileptic syndromes makes it difficult to compare series from different studies. We suggest that all epilepsies are symptomatic because they have a cause, whether genetic or acquired. The age of onset may point to specific aetiologies. Classifying epilepsy by aetiology might be a useful approach. We could establish 2 groups: a large group including epileptic syndromes with known aetiologies or associated with genetic syndromes which are very likely to cause epilepsy, and another group including epileptic syndromes with no known cause. Thanks to the advances in neuroimaging and genetics, the latter group is expected to become increasingly smaller.

Estudio descriptivo de epilepsias sintomáticas, según edad de inicio, controladas en una Unidad de Neuropediatría de referencia regional durante 3 años

Pacientes y métodosNiños con diagnóstico de epilepsia sintomática, controlados del 1 de enero del 2008 hasta el 31 de diciembre del 2010.

ResultadosDe 4595 niños en el periodo de estudio, recibieron el diagnóstico de epilepsia 605 (13,17%), siendo 277 (45,79%) epilepsias sintomáticas. Entre los pacientes que iniciaron la epilepsia por debajo del año de vida predominan las de etiología sintomática (67,72%). Entre los que la iniciaron entre 1-3 años, fueron sintomáticas el 61,39%. En cuanto a su etiología, ha sido: encefalopatías prenatales (24,46% del total de epilepsias), encefalopatías perinatales (9,26%), encefalopatías posnatales (3,14%), encefalopatías metabólicas y degenerativas (1,98%), esclerosis mesial temporal (1,32%), síndromes neurocutáneos (2,64%), malformaciones vasculares (0,17%), cavernomas (0,17%) y tumores intracraneales (2,48%). Algunas etiologías inician sus manifestaciones epilépticas por debajo del año de vida, como el síndrome de Down, la lisencefalia genética, la infección congénita por citomegalovirus, la encefalopatía hipóxico-isquémica, las encefalopatías metabólicas o la esclerosis tuberosa.

ConclusionesLa ausencia de una clasificación universalmente aceptada de los síndromes epilépticos dificulta comparaciones entre series. Sugerimos que todas las epilepsias son sintomáticas puesto que tienen causa, genética o adquirida. La edad de inicio orienta a determinadas etiologías. Una clasificación útil es la etiológica, con 2 grupos: un gran grupo con las etiologías establecidas o síndromes genéticos muy probables y otro de casos sin causa establecida, que con los avances en neuroimagen y genética cada vez será menor.

The term “epilepsy” encompasses a heterogeneous group of CNS diseases in terms of aetiology, prognosis, and treatment.1 These conditions may constitute the main manifestation of a wide range of disorders and result from the interaction between genetic and environmental factors.2,3

Symptomatic epilepsy is secondary to an underlying brain lesion and may manifest in any type of chronic encephalopathy, whether prenatal, perinatal, postnatal, or metabolic in origin.

We conducted a descriptive study of patients with symptomatic epilepsy, classified by aetiology and age at onset, who were followed up for 3 years at the neuropaediatric department of a regional reference hospital.

Material and methodsThe sample included all paediatric patients older than one month of age who were diagnosed with symptomatic epilepsy and assessed (either in the first visit or in follow-up consultations) by the neuropaediatric department at Hospital Infantil Universitario Miguel Servet, in Zaragoza, over a period of 3 years (from 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2010). The activities of this department, which was opened to the public in 1990, are recorded in a digital database which includes all relevant data on each patient.4–9 Patient data are updated to reflect any significant changes in clinical progression, complementary test results, or treatment.

We conducted a retrospective descriptive study based on the data provided by our patients’ clinical histories, and collected epidemiological data, clinical characteristics of epilepsy, complementary test results, and data on patient progression.

A diagnosis of epilepsy is made when a patient experiences at least 2 spontaneous epileptic seizures.10 We excluded those patients with neonatal seizures and no subsequent epilepsy and those with isolated afebrile seizures, febrile seizures, and other acute symptomatic or provoked seizures.

Symptomatic epilepsy is diagnosed in patients with brain lesions (whether structural or metabolic) who display seizures and other neurological manifestations (the syndrome would still be present in the absence of seizures). In view of the wide range of causes of symptomatic epilepsy, we propose the following classification by aetiology: (1) prenatal encephalopathies; (2) perinatal encephalopathies; (3) postnatal encephalopathies; (4) metabolic and degenerative encephalopathies; (5) mesial temporal sclerosis; (6) neurocutaneous syndromes; (7) vascular malformations; (8) cavernomas; (9) intracranial tumours; and (10) other (Table 1).

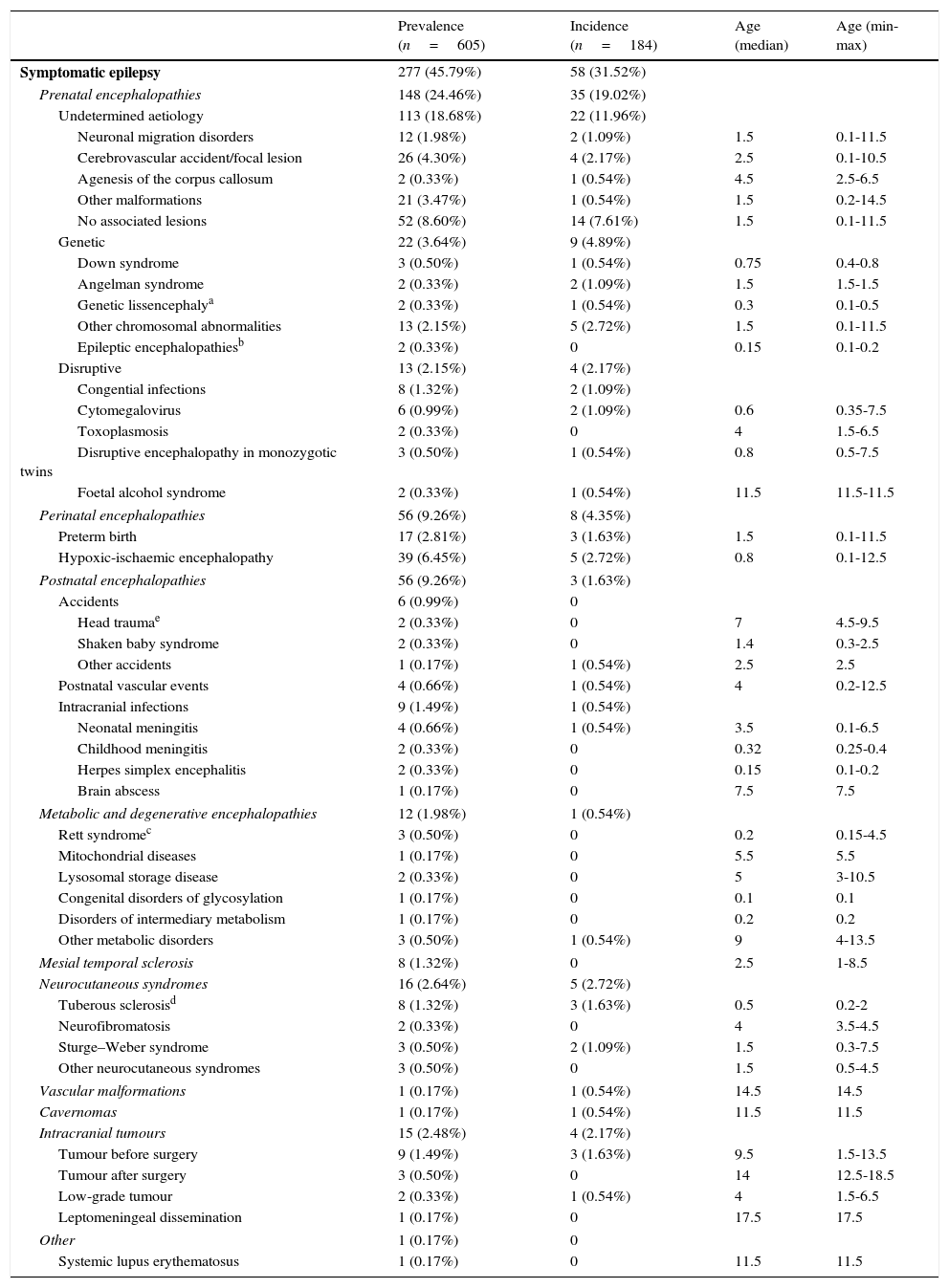

Prevalence, incidence, and age at onset (in years) of patients with symptomatic epilepsy (broken down by aetiology) with regard to the total number of patients with epilepsy (n=605) visiting our department during the study period (1 January 2008-31 December 2010).

| Prevalence (n=605) | Incidence (n=184) | Age (median) | Age (min-max) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptomatic epilepsy | 277 (45.79%) | 58 (31.52%) | ||

| Prenatal encephalopathies | 148 (24.46%) | 35 (19.02%) | ||

| Undetermined aetiology | 113 (18.68%) | 22 (11.96%) | ||

| Neuronal migration disorders | 12 (1.98%) | 2 (1.09%) | 1.5 | 0.1-11.5 |

| Cerebrovascular accident/focal lesion | 26 (4.30%) | 4 (2.17%) | 2.5 | 0.1-10.5 |

| Agenesis of the corpus callosum | 2 (0.33%) | 1 (0.54%) | 4.5 | 2.5-6.5 |

| Other malformations | 21 (3.47%) | 1 (0.54%) | 1.5 | 0.2-14.5 |

| No associated lesions | 52 (8.60%) | 14 (7.61%) | 1.5 | 0.1-11.5 |

| Genetic | 22 (3.64%) | 9 (4.89%) | ||

| Down syndrome | 3 (0.50%) | 1 (0.54%) | 0.75 | 0.4-0.8 |

| Angelman syndrome | 2 (0.33%) | 2 (1.09%) | 1.5 | 1.5-1.5 |

| Genetic lissencephalya | 2 (0.33%) | 1 (0.54%) | 0.3 | 0.1-0.5 |

| Other chromosomal abnormalities | 13 (2.15%) | 5 (2.72%) | 1.5 | 0.1-11.5 |

| Epileptic encephalopathiesb | 2 (0.33%) | 0 | 0.15 | 0.1-0.2 |

| Disruptive | 13 (2.15%) | 4 (2.17%) | ||

| Congential infections | 8 (1.32%) | 2 (1.09%) | ||

| Cytomegalovirus | 6 (0.99%) | 2 (1.09%) | 0.6 | 0.35-7.5 |

| Toxoplasmosis | 2 (0.33%) | 0 | 4 | 1.5-6.5 |

| Disruptive encephalopathy in monozygotic twins | 3 (0.50%) | 1 (0.54%) | 0.8 | 0.5-7.5 |

| Foetal alcohol syndrome | 2 (0.33%) | 1 (0.54%) | 11.5 | 11.5-11.5 |

| Perinatal encephalopathies | 56 (9.26%) | 8 (4.35%) | ||

| Preterm birth | 17 (2.81%) | 3 (1.63%) | 1.5 | 0.1-11.5 |

| Hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy | 39 (6.45%) | 5 (2.72%) | 0.8 | 0.1-12.5 |

| Postnatal encephalopathies | 56 (9.26%) | 3 (1.63%) | ||

| Accidents | 6 (0.99%) | 0 | ||

| Head traumae | 2 (0.33%) | 0 | 7 | 4.5-9.5 |

| Shaken baby syndrome | 2 (0.33%) | 0 | 1.4 | 0.3-2.5 |

| Other accidents | 1 (0.17%) | 1 (0.54%) | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Postnatal vascular events | 4 (0.66%) | 1 (0.54%) | 4 | 0.2-12.5 |

| Intracranial infections | 9 (1.49%) | 1 (0.54%) | ||

| Neonatal meningitis | 4 (0.66%) | 1 (0.54%) | 3.5 | 0.1-6.5 |

| Childhood meningitis | 2 (0.33%) | 0 | 0.32 | 0.25-0.4 |

| Herpes simplex encephalitis | 2 (0.33%) | 0 | 0.15 | 0.1-0.2 |

| Brain abscess | 1 (0.17%) | 0 | 7.5 | 7.5 |

| Metabolic and degenerative encephalopathies | 12 (1.98%) | 1 (0.54%) | ||

| Rett syndromec | 3 (0.50%) | 0 | 0.2 | 0.15-4.5 |

| Mitochondrial diseases | 1 (0.17%) | 0 | 5.5 | 5.5 |

| Lysosomal storage disease | 2 (0.33%) | 0 | 5 | 3-10.5 |

| Congenital disorders of glycosylation | 1 (0.17%) | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Disorders of intermediary metabolism | 1 (0.17%) | 0 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Other metabolic disorders | 3 (0.50%) | 1 (0.54%) | 9 | 4-13.5 |

| Mesial temporal sclerosis | 8 (1.32%) | 0 | 2.5 | 1-8.5 |

| Neurocutaneous syndromes | 16 (2.64%) | 5 (2.72%) | ||

| Tuberous sclerosisd | 8 (1.32%) | 3 (1.63%) | 0.5 | 0.2-2 |

| Neurofibromatosis | 2 (0.33%) | 0 | 4 | 3.5-4.5 |

| Sturge–Weber syndrome | 3 (0.50%) | 2 (1.09%) | 1.5 | 0.3-7.5 |

| Other neurocutaneous syndromes | 3 (0.50%) | 0 | 1.5 | 0.5-4.5 |

| Vascular malformations | 1 (0.17%) | 1 (0.54%) | 14.5 | 14.5 |

| Cavernomas | 1 (0.17%) | 1 (0.54%) | 11.5 | 11.5 |

| Intracranial tumours | 15 (2.48%) | 4 (2.17%) | ||

| Tumour before surgery | 9 (1.49%) | 3 (1.63%) | 9.5 | 1.5-13.5 |

| Tumour after surgery | 3 (0.50%) | 0 | 14 | 12.5-18.5 |

| Low-grade tumour | 2 (0.33%) | 1 (0.54%) | 4 | 1.5-6.5 |

| Leptomeningeal dissemination | 1 (0.17%) | 0 | 17.5 | 17.5 |

| Other | 1 (0.17%) | 0 | ||

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 1 (0.17%) | 0 | 11.5 | 11.5 |

The term “encephalopathy” has been used according to its etymological meaning (that is, brain disease) regardless its clinical consequences and whether it is diffuse or localised. Postnatal encephalopathies are those secondary to CNS infections, trauma, and postnatal cerebrovascular accidents. Prenatal encephalopathies are diagnosed based on such clinical and/or neuroimaging criteria as presence of polyhydramnios, dysmorphic facial features, and associated non-neurological malformations, in addition to a lack of evidence of perinatal or postnatal noxa. Neuroimaging findings of agenesis of the corpus callosum, neuronal migration disorders, or other malformations are suggestive of prenatal encephalopathies.

ResultsThe database of the neuropaediatric department included 15808 patients at the time of the study, 4595 of whom were evaluated by the department during the study period. In 1654 patients (35.99%), the reason for consultation was paroxysmal disorders; 605 patients were diagnosed with epilepsy (13.17% of the patient total, 36.58% of those with paroxysmal disorders). Epilepsy was symptomatic in 277 cases (45.79%); 54.71% of these were boys and 45.29% were girls. During the study period, 184 new cases of epilepsy were diagnosed, 58 of which (31.52%) were classified as symptomatic epilepsy. Mean follow-up time for all patients with epilepsy was 6.21 years; patients with symptomatic epilepsy were followed up for a mean of 8.13 years.

Mean age at epilepsy onset was 4.78 years, or 3.53 years in the case of symptomatic epilepsy. Epilepsy onset most frequently occurred during the first year of life (26.12% of all patients with epilepsy). According to age group, symptomatic epilepsy was the most common type among patients developing epilepsy before one year of age (67.72%) and between the ages of 1 and 3 (61.39%). From a clinical viewpoint, 71.74% of all patients with symptomatic epilepsy presented focal or partial seizures, 13.41% generalised convulsive seizures, 12.68% infantile spasms, and the remaining patients presented unclassified seizures (4.71% convulsive status epilepticus). Of the patients with symptomatic epilepsy, 2.54% had a family history of epilepsy, 15.22% had experienced seizures during the neonatal period, and 10.14% had experienced febrile seizures.

Table 1 shows the incidence, prevalence, and age at onset of symptomatic epilepsy, broken down by aetiology.

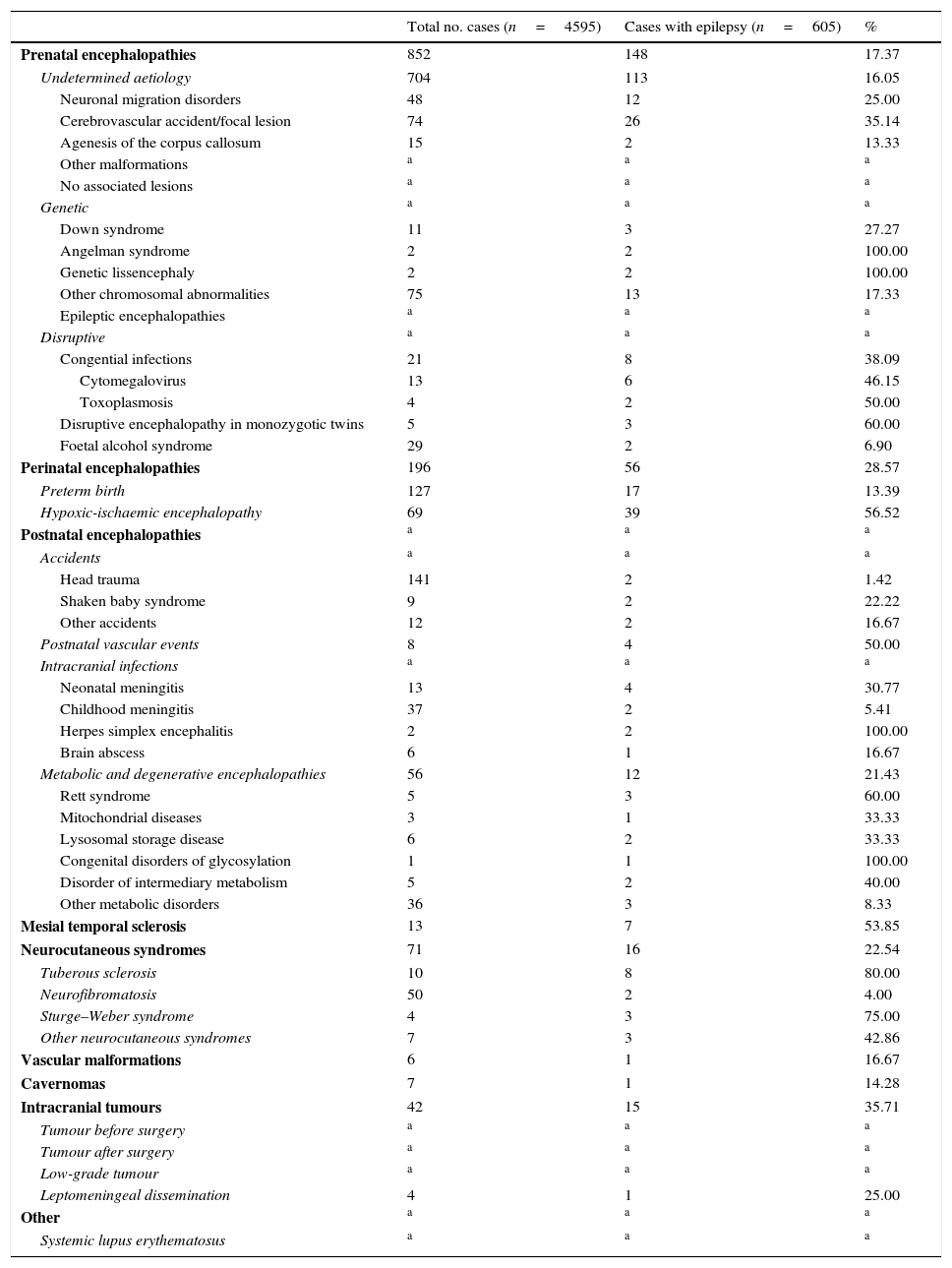

Table 2 describes the frequency of each of the conditions associated with epilepsy in the total sample of patients included in the neuropaediatric department database during the study period and in the subsample of patients with epilepsy.

Frequency of each of the conditions associated with epilepsy in our sample of 4595 patients assessed at the neuropaediatric department during the study period (1 January 2008-31 December 2010) and in the subsample of patients with epilepsy.

| Total no. cases (n=4595) | Cases with epilepsy (n=605) | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prenatal encephalopathies | 852 | 148 | 17.37 |

| Undetermined aetiology | 704 | 113 | 16.05 |

| Neuronal migration disorders | 48 | 12 | 25.00 |

| Cerebrovascular accident/focal lesion | 74 | 26 | 35.14 |

| Agenesis of the corpus callosum | 15 | 2 | 13.33 |

| Other malformations | a | a | a |

| No associated lesions | a | a | a |

| Genetic | a | a | a |

| Down syndrome | 11 | 3 | 27.27 |

| Angelman syndrome | 2 | 2 | 100.00 |

| Genetic lissencephaly | 2 | 2 | 100.00 |

| Other chromosomal abnormalities | 75 | 13 | 17.33 |

| Epileptic encephalopathies | a | a | a |

| Disruptive | a | a | a |

| Congential infections | 21 | 8 | 38.09 |

| Cytomegalovirus | 13 | 6 | 46.15 |

| Toxoplasmosis | 4 | 2 | 50.00 |

| Disruptive encephalopathy in monozygotic twins | 5 | 3 | 60.00 |

| Foetal alcohol syndrome | 29 | 2 | 6.90 |

| Perinatal encephalopathies | 196 | 56 | 28.57 |

| Preterm birth | 127 | 17 | 13.39 |

| Hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy | 69 | 39 | 56.52 |

| Postnatal encephalopathies | a | a | a |

| Accidents | a | a | a |

| Head trauma | 141 | 2 | 1.42 |

| Shaken baby syndrome | 9 | 2 | 22.22 |

| Other accidents | 12 | 2 | 16.67 |

| Postnatal vascular events | 8 | 4 | 50.00 |

| Intracranial infections | a | a | a |

| Neonatal meningitis | 13 | 4 | 30.77 |

| Childhood meningitis | 37 | 2 | 5.41 |

| Herpes simplex encephalitis | 2 | 2 | 100.00 |

| Brain abscess | 6 | 1 | 16.67 |

| Metabolic and degenerative encephalopathies | 56 | 12 | 21.43 |

| Rett syndrome | 5 | 3 | 60.00 |

| Mitochondrial diseases | 3 | 1 | 33.33 |

| Lysosomal storage disease | 6 | 2 | 33.33 |

| Congenital disorders of glycosylation | 1 | 1 | 100.00 |

| Disorder of intermediary metabolism | 5 | 2 | 40.00 |

| Other metabolic disorders | 36 | 3 | 8.33 |

| Mesial temporal sclerosis | 13 | 7 | 53.85 |

| Neurocutaneous syndromes | 71 | 16 | 22.54 |

| Tuberous sclerosis | 10 | 8 | 80.00 |

| Neurofibromatosis | 50 | 2 | 4.00 |

| Sturge–Weber syndrome | 4 | 3 | 75.00 |

| Other neurocutaneous syndromes | 7 | 3 | 42.86 |

| Vascular malformations | 6 | 1 | 16.67 |

| Cavernomas | 7 | 1 | 14.28 |

| Intracranial tumours | 42 | 15 | 35.71 |

| Tumour before surgery | a | a | a |

| Tumour after surgery | a | a | a |

| Low-grade tumour | a | a | a |

| Leptomeningeal dissemination | 4 | 1 | 25.00 |

| Other | a | a | a |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | a | a | a |

Despite advances made in epileptology, the published epidemiological studies report significantly different results due to methodological issues and a lack of heterogeneous criteria, which make them difficult to perform.2,3,11,12 The percentage of patients with symptomatic epilepsy in other comparable series ranges from 18.1% to 50%3,13–17; our study reported a prevalence of 45.79% and an incidence of 31.52%. In our series, as in most studies, there were slightly more boys than girls.18–20

Epileptic syndromes depend on age, and their clinical and EEG characteristics depend on the degree of brain maturation,21–23 as shown in our study. As a result, certain aetiologies and types of epilepsy are more frequent in some age groups than in others.

Symptomatic epilepsy manifests at younger ages (in our sample, 67.72% of cases during the first year of life). Presence of brain lesions is the most frequent cause of early-onset epileptic seizures in paediatric patients. Many of the lesions responsible for early-onset childhood epilepsy occur during the prenatal or perinatal period.24 An infant manifesting epilepsy during the first month of life is very likely to develop symptomatic epilepsy (89.74% in our sample). In our experience, epilepsy at this age is fundamentally caused by perinatal (43.59%) or prenatal encephalopathies (38.46%). Likewise, symptomatic epilepsy is the most frequent type (66.67% in our study) in infants aged between one and 3 months, with prenatal encephalopathies being the most frequent aetiology (33.33%). In the group of children aged 3-12 months, symptomatic epilepsy was also the most frequent type (58.42%).

In our series, some of the conditions causing epilepsy triggered epileptic symptoms before the age of one year; some examples are Down syndrome, genetic lissencephaly, congenital cytomegalovirus infection, hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy, metabolic encephalopathies, and tuberous sclerosis (Table 1).

Patients experiencing the first manifestations of epilepsy between the ages of one and 3 years are also more likely to have symptomatic epilepsy (61.39% in our sample; prenatal and perinatal encephalopathies and mesial temporal sclerosis).

Symptomatic epilepsy is less frequent in patients older than 3 years (31.21%); intracranial infections, accidents, intracranial tumours, or vascular malformation are the main aetiologies.

In the total sample, prenatal encephalopathies explain 53.42% of all cases of symptomatic epilepsy (24.46% of the total number of patients with epilepsies). Prenatal encephalopathies develop before the child is born and may be disruptive (vascular problems, toxicity, infections, etc.) or be genetically determined. On many occasions, clinical data and the correct interpretation of neuroimaging findings (brain malformations may have different interpretations depending on the stage of pregnancy) point to a prenatal origin of epilepsy but do not allow us to identify its aetiology.25,26 In our sample, aetiology remained uncertain in 113 patients: 40.79% of all cases of symptomatic epilepsy and 76.35% of all cases of epilepsy secondary to prenatal encephalopathy.

Migration/proliferation disorders and other malformations of cortical development are the most frequent brain malformations. These are very frequently associated with epileptic seizures and refractory to medical treatment.27 Manifestations of these entities are very heterogeneous (depending on the aetiology and the stage of brain development), which will determine functionality and the degree of epileptogenicity.28 Migration involves multiple factors, both genetic and environmental, and may therefore be altered by a number of causes, including hypoxic-ischaemic events, infections (such as cytomegalovirus infection), drugs, toxic agents, poison, or radiation.29 In our sample, 12 epileptic children had a neuronal migration disorder or cortical dysplasia of unknown aetiology.

In our experience, prenatal encephalopathies are associated with epilepsy in 17.37% of the cases; among these, Angelman syndrome or genetic lissencephaly present with epilepsy in 100% of the patients, congenital toxoplasmosis in 50% and cytomegalovirus infection in 46.15%.

Survival rates of preterm children and newborns with perinatal asphyxia have increased in the past years due to improvements in obstetric care and recent advances in neonatology; however, severe neurological sequelae such as epilepsy still remain.30,31 In our series, perinatal encephalopathies represent 9.26% of all cases of epilepsy and 20.22% of all cases of symptomatic epilepsy. However, the incidence of epilepsy is higher in patients with hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy (56.52%) than in preterm infants (13.39%). This may be explained by the fact that hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy is diagnosed based on findings of brain lesions, whereas the incidence of brain lesions (for example, periventricular leukomalacia) in preterm children has decreased considerably due to improvements in neonatal care.

Head trauma is a frequent cause of epilepsy; incidence of late-onset epilepsy following severe trauma is estimated to range from 1% to 57%,32 with a higher risk of epilepsy in cases of open wounds, intracranial haematoma, or seizures during the first week after trauma.33,34 Our sample only included 2 cases of head trauma (0.72% of all cases of symptomatic epilepsy): both presented intracranial haematomas, one of them in association with an open wound; none of them experienced seizures during the first week.

Mesial temporal sclerosis is another possible cause of epilepsy, although its pathogenesis is still to be determined. Several trigger factors of hippocampal lesion (neuronal loss and subsequent sclerosis) have been described, including head trauma, perinatal cerebral infarction, and intracranial infections.35,36 Furthermore, a genetic predisposition to this syndrome has also been suggested.35,37 Our sample included 7 patients (1.16% of all cases of epilepsy and 2.52% of all cases of symptomatic epilepsy) in whom the aetiology of the lesion was not identified and 2 patients with mesial sclerosis and congenital cytomegalovirus infection. In our series, 53.85% of the patients with mesial temporal sclerosis had epilepsy.

In general terms, 22.54% of all the patients with neurocutaneous syndromes in our sample had epilepsy. Although neurofibromatosis type 1 is the most frequent neurocutaneous syndrome (70.42% of all neurocutaneous syndromes in our series), the prevalence rate of epilepsy in these patients is estimated to be lower than that of other neurocutaneous syndromes, at 3%-8%.38,39 In our series, 4% of patients had epilepsy (2 of the 50 patients with neurofibromatosis type 1). However, patients with tuberous sclerosis, though less numerous, required more follow-up visits to the neuropaediatric department than those with neurofibromatosis type 1 due to the high rates of epilepsy associated with this condition, ranging from 78% to 95%38,40,41 (80% in our series; 8 out of the 10 patients with tuberous sclerosis had epilepsy). Furthermore, epilepsy frequently manifests during the first year of life in these patients. In the case of Sturge–Weber syndrome, incidence of epilepsy is estimated at 80% of the cases with unilateral involvement and almost 93% of the cases of bilateral involvement. Our results are in line with these rates: 75% of the patients with Sturge–Weber syndrome had epilepsy (3 out of 4).

Seizures may appear as the initial manifestation of a brain tumour (20%-50%), frequently in association with other neurological symptoms.42,43 The estimated incidence of brain tumours as a cause of epilepsy in paediatric patients ranges from 0.2% to 6%43,44 (2.48% in our series; 5.42% of all cases of symptomatic epilepsy). Of the 15 patients with brain tumours, seizures were the initial manifestation in 6 patients (40%) and occurred during disease progression in the remaining patients.

Age at onset is essential in the management of childhood epilepsy. Neuroimaging and EEG studies may be sufficient in older children, but infants usually require comprehensive metabolic and genetic studies.21 No cases of autoimmune epilepsy were identified in our series; however, increasing numbers of cases are being reported. An autoimmune origin should therefore be considered to provide appropriate diagnosis and treatment.45–47 The most frequent cause of early-onset epilepsy, especially in patients experiencing seizures between the ages of one and 4 months, is a severe brain disorder; these patients usually display poor response to antiepileptic treatment and a poor prognosis in terms of neurological and developmental impairment.48 Early-onset epilepsy is rarely due to inborn errors of metabolism, which may on occasions be treated with specific treatment (vitamin supplementation or ketogenic diet) when patients do not respond to antiepileptic drugs. In view of the importance of prognosis, and the risk of further cases (these disorders are frequently genetic), together with the limited number of diseases which respond to specific treatment, a diagnostic and therapeutic protocol should be designed to provide early treatment, when possible, and to identify the cause. This protocol should also consider treatment with vitamins, only after biological samples have been collected. In patients of any age with refractory focal epilepsy, conventional and functional neuroimaging studies should be conducted to rule out lesions potentially treatable with surgery (lesion resection may be effective in these patients).49,50

Lack of a universally accepted classification of epilepsy syndromes make it difficult to compare the results of published series,51,52 starting with terminology. Epileptic encephalopathies associated with mutations, as in our patients with STXBP1 and CDKL5 mutations, and Dravet syndrome (which was not included in our study since it is normally considered to be idiopathic) may be classified as symptomatic (genetically determined encephalopathy with neurodevelopmental dysfunction not necessarily secondary to epilepsy) and idiopathic (genetically determined and with epilepsy as the main manifestation). Non-disruptive prenatal encephalopathies; neurocutaneous syndromes; metabolic and degenerative diseases; and many cases of vascular malformations, cavernomas, brain tumours, and mesial temporal sclerosis are genetically determined. In our view, all epilepsies are symptomatic since they all have a determined aetiology, whether genetic or acquired. Age at onset is sometimes helpful in aetiological diagnosis.

An aetiological classification of epilepsy into 2 groups may be very useful. This classification establishes a large group including epilepsies with known aetiologies or associated with genetic syndromes which are very likely to cause epilepsy, and another group of epileptic syndromes with no known cause. The latter group is expected to decrease due to advances in neuroimaging and genetics.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Ochoa-Gómez L, López-Pisón J, Fuertes-Rodrigo C, Fernando-Martínez R, Samper-Villagrasa P, Monge-Galindo L, et al. Estudio descriptivo de las epilepsias sintomáticas según edad de inicio controladas durante 3 años en una Unidad de Neuropediatría de referencia regional. Neurología. 2017;32:455–462.