Hypoglycaemic encephalopathy can be defined as the presence of coma or stupor in patients with glucose levels below 50mg/dL, persisting for more than 24hours despite normalisation of blood glucose levels, in the absence of other possible aetiologies.1 This condition is rare but potentially severe, with a mortality rate of up to 50%, depending on the series.1–3 We present the case of a patient with typical clinical symptoms and neuroimaging findings.

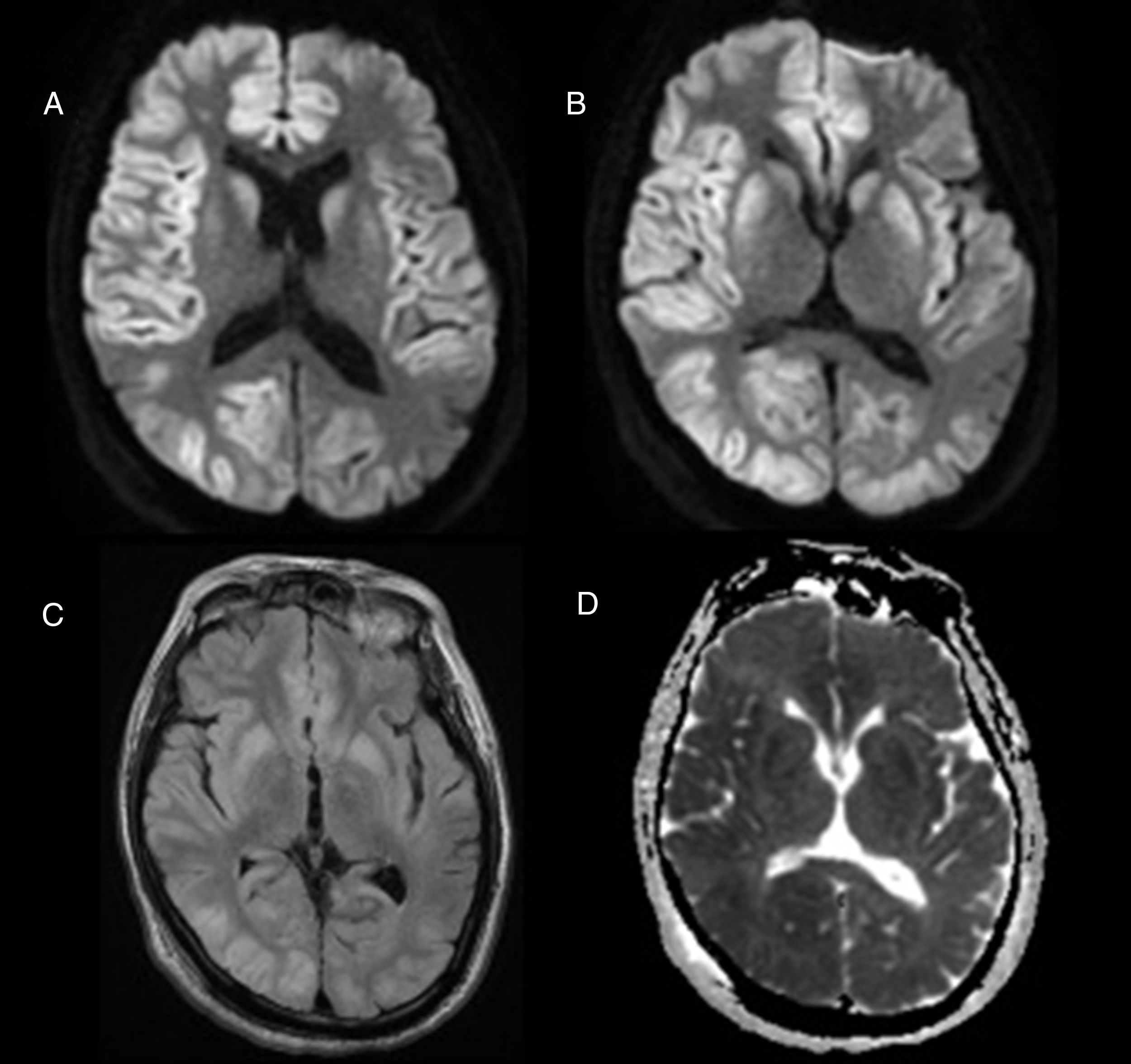

The patient was a 63-year-old man who had been institutionalised in the previous year due to progressive cognitive impairment (frontotemporal dementia type), with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with sulphonylureas. During the course of a urinary tract infection, he was found in the early hours of the morning in a coma and with hypoglycaemia (19mg/dL); the duration of that situation could not be determined, and the patient showed no clinical response to the immediate metabolic correction. Upon arrival at our hospital, the patient presented low-grade fever, a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 3, roving eye movement, and decerebrate rigidity of the left arm, with no other pathological findings; he was admitted to the intermediate care unit. During hospitalisation, complementary tests reliably ruled out an infectious, epileptic, or vascular origin of the symptoms: no alterations were detected in the blood test; CT and CT angiography showed no signs of acute ischaemia or haemorrhage or large-vessel occlusion; CSF analysis with blood formula, culture, and C-reactive protein with negative results for viruses; EEG revealed focal periodic epileptiform activity in the left frontotemporal area and diffuse theta slowing. A brain MRI study performed at 48hours displayed hyperintensities on T2-weighted, FLAIR, and diffusion-weighted sequences, with ADC maps showing restricted diffusion in cortical and deep grey matter with thalamic preservation; all these findings are compatible with persisting hypoglycaemia (Fig. 1). Despite metabolic correction and support measures, the patient's condition deteriorated and he eventually died.

Hypoglycaemic encephalopathy presents a wide clinical spectrum, and may manifest as epileptic seizures, focal neurological deficits, or decreased level of consciousness. It is important to rule out other causes of encephalopathy, especially toxic and metabolic causes. Diffusion-weighted brain MRI sequences show hyperintensities in the grey matter of the cortex, hippocampus, internal capsule, and basal ganglia in up to 70% of cases.1–7 Thalamic preservation is characteristic,2 unlike in the case of hypoxic encephalopathy. The extension of the lesions on MR images may predict prognosis and neurological sequelae,2,4,5 although the literature includes contradictory data.1 Several studies have associated basal ganglia involvement with poor prognosis,2 although some retrospective studies and clinical cases do not report this association.1 The brain's vulnerability to hypoglycaemia is believed to vary, even between areas of the cerebral cortex, with the parietal occipital cortex being the most vulnerable.4–6 No reports analyse whether patients with neurodegenerative diseases present a lower tolerability to situations of hypoglycaemia, which would explain the fatal outcome in our patient in spite of glycaemic correction.

In conclusion, hypoglycaemic encephalopathy is a relatively rare entity and should therefore be considered in patients with decreased level of consciousness and serum glucose levels below 50mg/dL in whom other causes have been ruled out; early glycaemic correction is vital in these cases. Despite the differences in vulnerability between brain areas, it seems clear that greater lesion extension on MR images is associated with higher morbidity and mortality rates; neuroimaging is therefore a useful tool not only for diagnosis but also for neurological prognosis.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez-Vázquez A, Vicente-Pascual M, Mayà-Casalprim G, Valldeoriola F. Neuroimagen en el diagnóstico y pronóstico de la encefalopatía hipoglucémica: a propósito de un caso. Neurología. 2020;35:131–132.

This work was submitted for presentation as a poster at the 21st Annual Meeting of the Catalan Society of Neurology.