Alzheimer disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia and is considered one of the main causes of disability and dependence affecting quality of life in elderly people and their families. Current pharmacological treatment includes acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine) and memantine; however, only one-third of patients respond to treatment. Genetic factors have been shown to play a role in this inter-individual variability in drug response.

DevelopmentWe review pharmacogenetic reports of AD-modifying drugs, the pharmacogenetic biomarkers included, and the phenotypes evaluated. We also discuss relevant methodological considerations for the design of pharmacogenetic studies into AD. A total of 33 pharmacogenetic reports were found; the majority of these focused on the variability in response to and metabolism of donepezil. Most of the patients included were from Caucasian populations, although some studies also include Korean, Indian, and Brazilian patients. CYP2D6 and APOE are the most frequently studied biomarkers. The associations proposed are controversial.

ConclusionsPotential pharmacogenetic biomarkers for AD have been identified; however, it is still necessary to conduct further research into other populations and to identify new biomarkers. This information could assist in predicting patient response to these drugs and contribute to better treatment decision-making in a context as complex as ageing.

La enfermedad de Alzheimer (EA) es la primera causa de demencia y una de las principales causas de discapacidad y dependencia que afecta la calidad de vida de los adultos mayores y de sus familiares. En la actualidad el manejo farmacológico disponible incluye a los fármacos inhibidores de la acetilcolinesterasa (donepezilo, galantamina, rivastigmina) y a la memantina. Sin embargo, se ha reportado que solo un tercio de los pacientes responden al tratamiento. Se ha evidenciado que los factores genéticos pueden explicar parte de la variabilidad en la respuesta a estos fármacos.

DesarrolloEn esta revisión se incluyen los estudios farmacogenéticos de fármacos modificadores de EA, los farmacogenes analizados y los fenotipos que fueron evaluados, además de las consideraciones metodológicas que es importante tomar en cuenta en este tipo de estudios. Se encontraron 33 reportes de farmacogenética de EA en los que principalmente se ha estudiado la variabilidad en la respuesta y en el metabolismo de donepezilo. La población más estudiada es la caucásica, aunque también han sido investigados coreanos, indios y brasileños. Los biomarcadores más estudiados son CYP2D6 y APOE. Los resultados de las asociaciones son controversiales.

ConclusionesSe han identificado posibles biomarcadores farmacogenéticos para el tratamiento de EA; sin embargo, se requieren más estudios farmacogenéticos en otras poblaciones que no han sido investigadas, así como profundizar en la identificación de los biomarcadores. Este conocimiento podría ayudar a predecir la respuesta a fármacos modificadores de EA y contribuiría a tomar mejores decisiones en el tratamiento de la enfermedad en un contexto tan complejo como es el envejecimiento.

Population ageing has given rise to a constant increase in the prevalence of chronic degenerative diseases, including such neurodegenerative diseases as dementia.1

Dementia is characterised by progressive, irreversible decline of behavioural and cognitive function (attention, orientation, memory, language, visuospatial function, executive function, and praxis), which progressively affects the quality of life of both the patients and their family and primary caregivers, contributing to the status of dementia as one of the leading causes of disability and dependence.2 For these reasons, the World Health Organization and the G8 have designated dementia a public health priority (in 2012 and 2014, respectively).1,3,4

The prevalence of dementia ranges from 5% to 10% among the population aged over 65, with the figure doubling every 5 years, reaching 25%-50% among those aged over 85.5

Alzheimer disease (AD), the most frequent cause of dementia, accounts for 60% of known cases and is defined as a neurodegenerative disease characterised by reduced neuronal function, which leads to synaptic loss and neuronal death; this causes lasting cognitive impairment, affects functional capacity, and progressively gives rise to dependence and disability.6–8

The number of patients with AD worldwide is estimated at 46 million, according to a 2015 report by Alzheimer's Disease International,1 and is projected to increase to 131.5 million by 2050. According to the report, nearly two-thirds of patients with dementia live in developing countries (including Latin American and Caribbean countries), and these regions are expected to present a greater increase in dementia cases in the coming years.1 Compared to more developed regions, access to specialised care in developing countries is limited. However, it should be noted that both in developed and in developing countries, an individual's social setting is an important risk factor for disease progression, and social services are essential in dementia care.

Since the discovery of amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) and tau protein, the main components of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, research into AD pathophysiology has yielded crucial information on the pathogenic molecular changes occurring at the neuronal level. Although these pathological changes constitute a sine qua non for the diagnosis of AD and are sufficient to cause cognitive and behavioural symptoms in some patients (memory loss and executive dysfunction affecting the activities of daily living), numerous risk factors are reported in patients developing symptoms after the age of 75 years.7,8 However, the pathophysiology of AD is very complex and much about the disease is yet to be understood; therefore, the development of novel drugs to cure AD or persistently slow or stop its progression has to date been unsuccessful.

Most cases of AD are sporadic and of multifactorial origin, with onset after the age of 65; the ɛ4 allele of the APOE gene has been identified as a significant risk factor in these cases.9 Familial forms follow an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, and onset is early. The main causal mutations affect the genes encoding amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin-1 (PSEN1), and presenilin-2 (PSEN2).

Two essential elements in the proper management of AD are early diagnosis and selection of the optimal treatment for each patient. Differential diagnosis of AD is complex, requiring imaging and neuropsychological studies, clinical assessment, and interviews with the primary caregiver or a family member. In 1984, the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) published the first diagnostic criteria for AD.10 These were updated in 2007 with the criteria proposed by Dubois et al.,11 and later revised in 2011 by the National Institute on Aging/Alzheimer Association; the latest version is known as the NIA-AA guidelines.12

In familial cases, genetic testing assists in accurate diagnosis of the disease, which is important for starting treatment early and providing genetic counselling to family members at risk of developing AD.13,14

Available treatments and variability in responseTwo types of treatment are currently available for AD. Non-pharmacological treatment includes memory training, social and mental stimulation, music therapy, aromatherapy, and physical exercise programmes, among other approaches. This strategy aims to slow the progression of cognitive and functional impairment; to conserve and promote the preserved cognitive, functional, and social skills and capacities; to restore unused cognitive abilities; to prevent disconnection from the environment; and to strengthen social relationships.2 Studies evaluating the efficacy of non-pharmacological treatment show that it is cost-effective and has positive results in terms of delaying institutionalisation and cognitive function; this results in improved quality of life for patients and caregivers.15,16

This review only addresses pharmacological treatment, which comprises a small number of drugs used in the management of dementia. Currently, the only drugs approved by international regulators are 3 acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine) and memantine. The efficacy of these drugs is variable and considered to be poor to moderate. A recent study calculated the rate of response to 3 of these drugs at 27.8%.17 Furthermore, AD treatments are associated with numerous adverse reactions, including diarrhoea, nausea, instability, vomiting, weight loss, stomach ulcers, syncope, and generalised seizures; in patients presenting these reactions, it may be necessary to withdraw treatment, limiting the therapeutic options available.18–20 Pharmacogenetic analysis may assist in explaining how genetic variability between patients contributes to these differences in treatment response and in the metabolism of drugs, including disease-modifying drugs.

This represents an opportunity for the development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic models for dementia, which may aim to preserve patients’ functional capacity and improve their quality of life. The challenges before us are novel, complex, and interesting, and represent a new vision of diagnosis and treatment, involving the tools of molecular biology and pharmacogenetics. Thus, there is a clear need to include analysis of molecular biomarkers in the early diagnosis of AD to assist in differential diagnosis, as well as in AD prevention and care.

This review describes the pharmacogenetic studies analysing disease-modifying drugs for AD and the pharmacogenes and phenotypes analysed, and addresses important methodological considerations to be taken into account in these studies. We performed a systematic review of articles published before February 2018 on the PubMed and PharmGKB databases, using the search terms “Alzheimer,” “pharmacogenetics,” “pharmacogenomics,” “donepezil,” “galantamine,” “rivastigmine,” and “memantine.”

Pharmacogenetics of disease-modifying drugs for Alzheimer diseaseBetween 75% and 85% of variability in treatment response to donepezil and other acetylcholinesterase inhibitors metabolised by cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes is thought to be explained by pharmacogenetic factors.21 Taking these factors into account may help to improve the safety and efficacy of AD treatment.

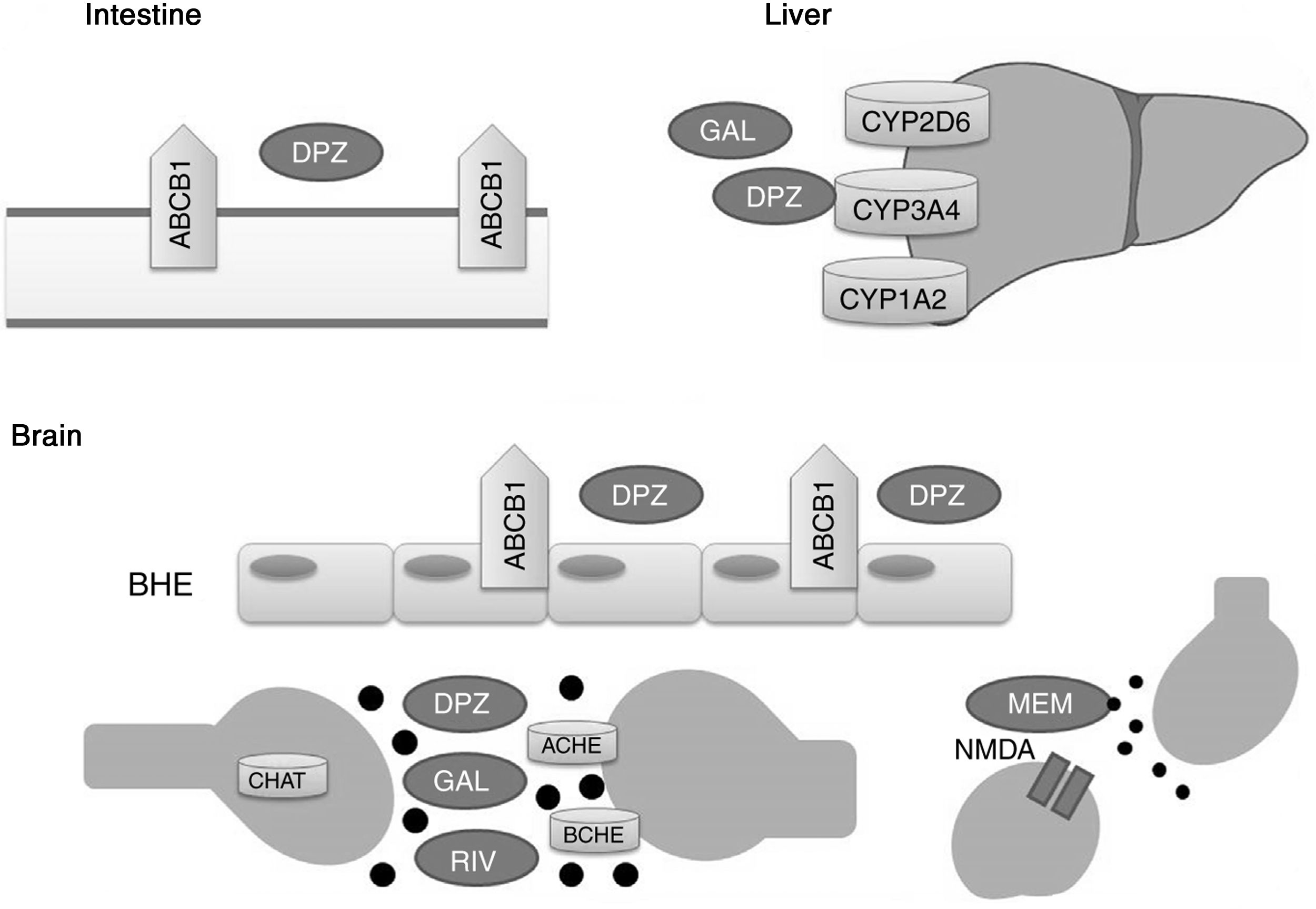

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine function through distinct metabolic pathways (Fig. 1). Donepezil and galantamine are metabolised in the liver, mainly by the enzymes CYP3A4, CYP2D6, and CYP1A2, whereas the biotransformation of rivastigmine occurs through the process of carbamylation. Hepatic metabolism of memantine is limited, and a considerable proportion of the drug is renally cleared. In terms of pharmacodynamics, the acetylcholinesterase inhibitors present different affinities for acetylcholinesterase (ACHE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BCHE): donepezil and galantamine inhibit ACHE more than BCHE, whereas rivastigmine inhibits both enzymes equally.21,22 ACHE is one of the most important enzymes in nerve functioning and response, as it catalyses acetylcholine hydrolysis in both the autonomic and peripheral nervous systems. BCHE hydrolyses both butyrylcholine and acetylcholine, and is distributed extensively in the liver, lungs, heart, and brain.23 The binding of drugs to ACHE and BCHE inhibits acetylcholine hydrolysis in the hippocampus, increasing the concentration of the neurotransmitter in the synaptic space and preventing it from binding to postsynaptic cholinergic receptors. This contributes to the improvement of cognitive symptoms, as cholinergic neurotransmission, which is involved in memory, attention, and emotion, is reported to be severely affected in AD.22

Proteins that interact with disease-modifying drugs for Alzheimer disease.

ACHE: acetylcholinesterase; BCHE: butyrylcholinesterase; BBB: blood–brain barrier; CHAT: choline acetyltransferase; DPZ: donepezil; GAL: galantamine; MEM: memantine; NMDA: N-methyl-D-aspartate; RIV: rivastigmine.

Memantine, in turn, is a moderate-affinity N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist that inhibits the pathological effect of elevated glutamate levels, which lead to the neuronal death and cell damage that characterise AD.22

P-glycoprotein has been shown to play a significant role in transporting donepezil across the blood–brain barrier.24

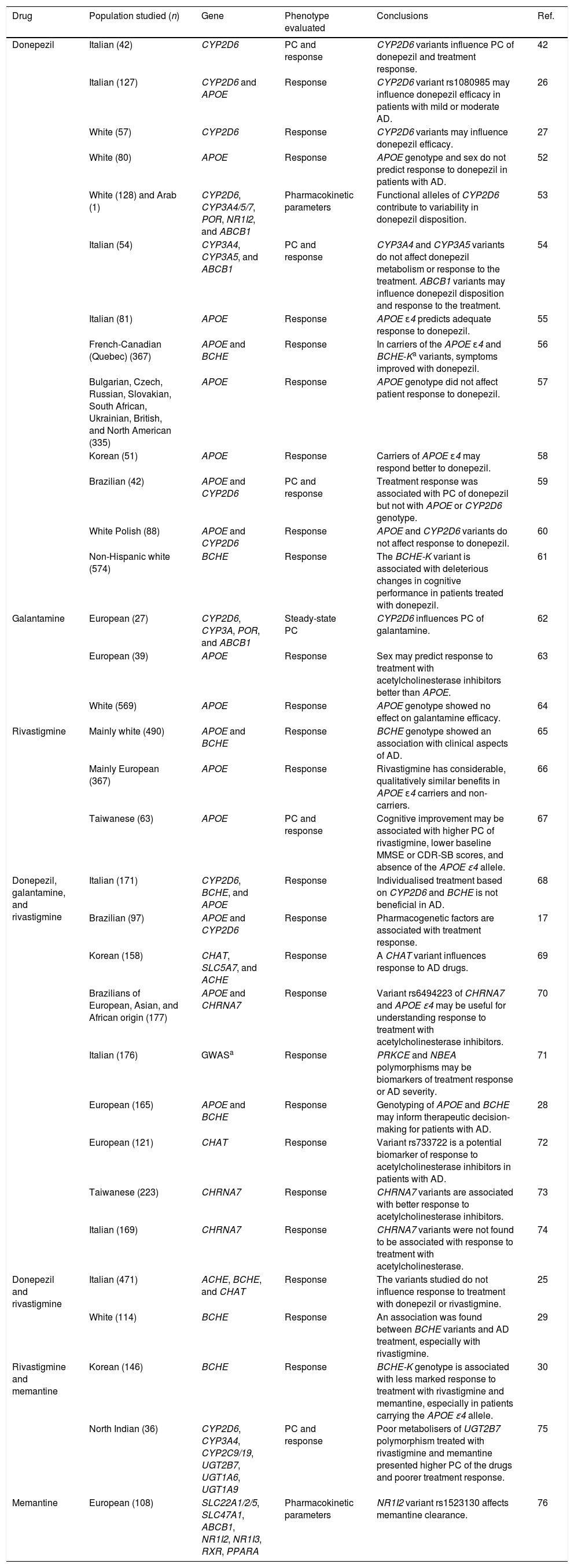

Pharmacogenetic studies into disease-modifying drugs for Alzheimer diseaseTable 1 summarises key information from pharmacogenetic studies into disease-modifying drugs for AD. We identified 33 articles, with donepezil being the most frequently studied drug (included in 24 studies); only 3 studies included patients treated with memantine. The most frequently studied population was white Europeans, although other studies were performed with Korean, Indian, and Brazilian populations, among others. Most studies evaluated the association between pharmacogenetic variants and response to disease-modifying drugs for AD; 8 also analysed pharmacokinetic parameters and plasma concentrations of the drugs.

Pharmacogenetic studies of disease-modifying drugs for Alzheimer disease.

| Drug | Population studied (n) | Gene | Phenotype evaluated | Conclusions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donepezil | Italian (42) | CYP2D6 | PC and response | CYP2D6 variants influence PC of donepezil and treatment response. | 42 |

| Italian (127) | CYP2D6 and APOE | Response | CYP2D6 variant rs1080985 may influence donepezil efficacy in patients with mild or moderate AD. | 26 | |

| White (57) | CYP2D6 | Response | CYP2D6 variants may influence donepezil efficacy. | 27 | |

| White (80) | APOE | Response | APOE genotype and sex do not predict response to donepezil in patients with AD. | 52 | |

| White (128) and Arab (1) | CYP2D6, CYP3A4/5/7, POR, NR1I2, and ABCB1 | Pharmacokinetic parameters | Functional alleles of CYP2D6 contribute to variability in donepezil disposition. | 53 | |

| Italian (54) | CYP3A4, CYP3A5, and ABCB1 | PC and response | CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 variants do not affect donepezil metabolism or response to the treatment. ABCB1 variants may influence donepezil disposition and response to the treatment. | 54 | |

| Italian (81) | APOE | Response | APOE ɛ4 predicts adequate response to donepezil. | 55 | |

| French-Canadian (Quebec) (367) | APOE and BCHE | Response | In carriers of the APOE ɛ4 and BCHE-Ka variants, symptoms improved with donepezil. | 56 | |

| Bulgarian, Czech, Russian, Slovakian, South African, Ukrainian, British, and North American (335) | APOE | Response | APOE genotype did not affect patient response to donepezil. | 57 | |

| Korean (51) | APOE | Response | Carriers of APOE ɛ4 may respond better to donepezil. | 58 | |

| Brazilian (42) | APOE and CYP2D6 | PC and response | Treatment response was associated with PC of donepezil but not with APOE or CYP2D6 genotype. | 59 | |

| White Polish (88) | APOE and CYP2D6 | Response | APOE and CYP2D6 variants do not affect response to donepezil. | 60 | |

| Non-Hispanic white (574) | BCHE | Response | The BCHE-K variant is associated with deleterious changes in cognitive performance in patients treated with donepezil. | 61 | |

| Galantamine | European (27) | CYP2D6, CYP3A, POR, and ABCB1 | Steady-state PC | CYP2D6 influences PC of galantamine. | 62 |

| European (39) | APOE | Response | Sex may predict response to treatment with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors better than APOE. | 63 | |

| White (569) | APOE | Response | APOE genotype showed no effect on galantamine efficacy. | 64 | |

| Rivastigmine | Mainly white (490) | APOE and BCHE | Response | BCHE genotype showed an association with clinical aspects of AD. | 65 |

| Mainly European (367) | APOE | Response | Rivastigmine has considerable, qualitatively similar benefits in APOE ɛ4 carriers and non-carriers. | 66 | |

| Taiwanese (63) | APOE | PC and response | Cognitive improvement may be associated with higher PC of rivastigmine, lower baseline MMSE or CDR-SB scores, and absence of the APOE ɛ4 allele. | 67 | |

| Donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine | Italian (171) | CYP2D6, BCHE, and APOE | Response | Individualised treatment based on CYP2D6 and BCHE is not beneficial in AD. | 68 |

| Brazilian (97) | APOE and CYP2D6 | Response | Pharmacogenetic factors are associated with treatment response. | 17 | |

| Korean (158) | CHAT, SLC5A7, and ACHE | Response | A CHAT variant influences response to AD drugs. | 69 | |

| Brazilians of European, Asian, and African origin (177) | APOE and CHRNA7 | Response | Variant rs6494223 of CHRNA7 and APOE ɛ4 may be useful for understanding response to treatment with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. | 70 | |

| Italian (176) | GWASa | Response | PRKCE and NBEA polymorphisms may be biomarkers of treatment response or AD severity. | 71 | |

| European (165) | APOE and BCHE | Response | Genotyping of APOE and BCHE may inform therapeutic decision-making for patients with AD. | 28 | |

| European (121) | CHAT | Response | Variant rs733722 is a potential biomarker of response to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in patients with AD. | 72 | |

| Taiwanese (223) | CHRNA7 | Response | CHRNA7 variants are associated with better response to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. | 73 | |

| Italian (169) | CHRNA7 | Response | CHRNA7 variants were not found to be associated with response to treatment with acetylcholinesterase. | 74 | |

| Donepezil and rivastigmine | Italian (471) | ACHE, BCHE, and CHAT | Response | The variants studied do not influence response to treatment with donepezil or rivastigmine. | 25 |

| White (114) | BCHE | Response | An association was found between BCHE variants and AD treatment, especially with rivastigmine. | 29 | |

| Rivastigmine and memantine | Korean (146) | BCHE | Response | BCHE-K genotype is associated with less marked response to treatment with rivastigmine and memantine, especially in patients carrying the APOE ɛ4 allele. | 30 |

| North Indian (36) | CYP2D6, CYP3A4, CYP2C9/19, UGT2B7, UGT1A6, UGT1A9 | PC and response | Poor metabolisers of UGT2B7 polymorphism treated with rivastigmine and memantine presented higher PC of the drugs and poorer treatment response. | 75 | |

| Memantine | European (108) | SLC22A1/2/5, SLC47A1, ABCB1, NR1I2, NR1I3, RXR, PPARA | Pharmacokinetic parameters | NR1I2 variant rs1523130 affects memantine clearance. | 76 |

CDR-SB: Clinical Dementia Rating – Sum of Boxes; PC: plasma concentration; AD: Alzheimer disease; GWAS: genome-wide association study; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; Ref.: reference.

The majority of the positive associations reported were found between CYP2D6 variants and plasma concentrations of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and the response to these drugs. Results from studies into the association between treatment response and variants of APOE and BCHE were more controversial. Although few studies included patients treated with memantine, variants of UGT2B7, BCHE, and NR1I2 are reported to be associated with pharmacokinetic parameters and with variation in response to the drug (Table 1).

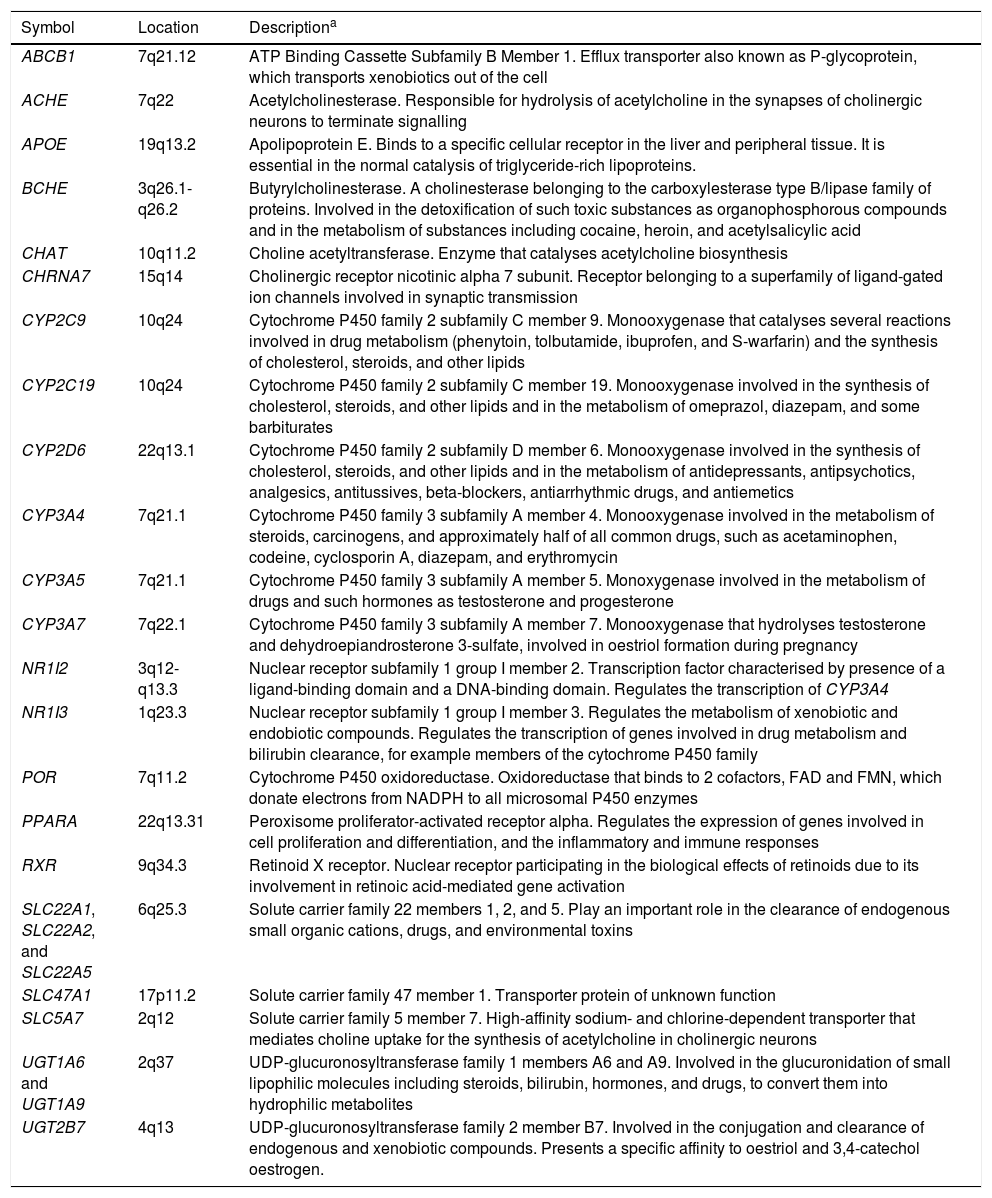

The pharmacogenes considered in the studies reviewed include ABCB1, ACHE, APOE, BCHE, CHAT, CHRNA7, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP3A7, NR1I2, NR1I3, POR, PPAR, RXR, SLC22A1/2/5, SLC47A1, SLC5A7, UGT1A6, UGT1A9, and UGT2B7. Descriptions of these genes are given in Table 2. The APOE gene has mainly been studied in relation to the risk of developing AD. Carriers of the ɛ4 allele are reported to be at greater risk of AD compared to those with the ɛ3 allele; the ɛ2 allele has been identified as a protective factor.9 The ACHE, BCHE, CHAT, CHRNA7, and SLC5A7 genes participate directly in acetylcholine formation and metabolism.25 Other genes analysed in the pharmacogenetic studies reviewed are involved in the transport, metabolism, and inhibition of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (e.g., ABCB1, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, and CYP3A7) or in the transcription and expression of these genes (e.g., POR, NR1I2, NR1I3, RXR, and PPAR).

Genes included in pharmacogenetic studies of disease-modifying drugs for Alzheimer disease.

| Symbol | Location | Descriptiona |

|---|---|---|

| ABCB1 | 7q21.12 | ATP Binding Cassette Subfamily B Member 1. Efflux transporter also known as P-glycoprotein, which transports xenobiotics out of the cell |

| ACHE | 7q22 | Acetylcholinesterase. Responsible for hydrolysis of acetylcholine in the synapses of cholinergic neurons to terminate signalling |

| APOE | 19q13.2 | Apolipoprotein E. Binds to a specific cellular receptor in the liver and peripheral tissue. It is essential in the normal catalysis of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. |

| BCHE | 3q26.1-q26.2 | Butyrylcholinesterase. A cholinesterase belonging to the carboxylesterase type B/lipase family of proteins. Involved in the detoxification of such toxic substances as organophosphorous compounds and in the metabolism of substances including cocaine, heroin, and acetylsalicylic acid |

| CHAT | 10q11.2 | Choline acetyltransferase. Enzyme that catalyses acetylcholine biosynthesis |

| CHRNA7 | 15q14 | Cholinergic receptor nicotinic alpha 7 subunit. Receptor belonging to a superfamily of ligand-gated ion channels involved in synaptic transmission |

| CYP2C9 | 10q24 | Cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily C member 9. Monooxygenase that catalyses several reactions involved in drug metabolism (phenytoin, tolbutamide, ibuprofen, and S-warfarin) and the synthesis of cholesterol, steroids, and other lipids |

| CYP2C19 | 10q24 | Cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily C member 19. Monooxygenase involved in the synthesis of cholesterol, steroids, and other lipids and in the metabolism of omeprazol, diazepam, and some barbiturates |

| CYP2D6 | 22q13.1 | Cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily D member 6. Monooxygenase involved in the synthesis of cholesterol, steroids, and other lipids and in the metabolism of antidepressants, antipsychotics, analgesics, antitussives, beta-blockers, antiarrhythmic drugs, and antiemetics |

| CYP3A4 | 7q21.1 | Cytochrome P450 family 3 subfamily A member 4. Monooxygenase involved in the metabolism of steroids, carcinogens, and approximately half of all common drugs, such as acetaminophen, codeine, cyclosporin A, diazepam, and erythromycin |

| CYP3A5 | 7q21.1 | Cytochrome P450 family 3 subfamily A member 5. Monoxygenase involved in the metabolism of drugs and such hormones as testosterone and progesterone |

| CYP3A7 | 7q22.1 | Cytochrome P450 family 3 subfamily A member 7. Monooxygenase that hydrolyses testosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone 3-sulfate, involved in oestriol formation during pregnancy |

| NR1I2 | 3q12-q13.3 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group I member 2. Transcription factor characterised by presence of a ligand-binding domain and a DNA-binding domain. Regulates the transcription of CYP3A4 |

| NR1I3 | 1q23.3 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group I member 3. Regulates the metabolism of xenobiotic and endobiotic compounds. Regulates the transcription of genes involved in drug metabolism and bilirubin clearance, for example members of the cytochrome P450 family |

| POR | 7q11.2 | Cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase. Oxidoreductase that binds to 2 cofactors, FAD and FMN, which donate electrons from NADPH to all microsomal P450 enzymes |

| PPARA | 22q13.31 | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. Regulates the expression of genes involved in cell proliferation and differentiation, and the inflammatory and immune responses |

| RXR | 9q34.3 | Retinoid X receptor. Nuclear receptor participating in the biological effects of retinoids due to its involvement in retinoic acid-mediated gene activation |

| SLC22A1, SLC22A2, and SLC22A5 | 6q25.3 | Solute carrier family 22 members 1, 2, and 5. Play an important role in the clearance of endogenous small organic cations, drugs, and environmental toxins |

| SLC47A1 | 17p11.2 | Solute carrier family 47 member 1. Transporter protein of unknown function |

| SLC5A7 | 2q12 | Solute carrier family 5 member 7. High-affinity sodium- and chlorine-dependent transporter that mediates choline uptake for the synthesis of acetylcholine in cholinergic neurons |

| UGT1A6 and UGT1A9 | 2q37 | UDP-glucuronosyltransferase family 1 members A6 and A9. Involved in the glucuronidation of small lipophilic molecules including steroids, bilirubin, hormones, and drugs, to convert them into hydrophilic metabolites |

| UGT2B7 | 4q13 | UDP-glucuronosyltransferase family 2 member B7. Involved in the conjugation and clearance of endogenous and xenobiotic compounds. Presents a specific affinity to oestriol and 3,4-catechol oestrogen. |

ATP: adenosine triphosphate; FAD: flavin adenine dinucleotide; FMN: flavin mononucleotide; NADPH: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; UDP: uridine diphosphate.

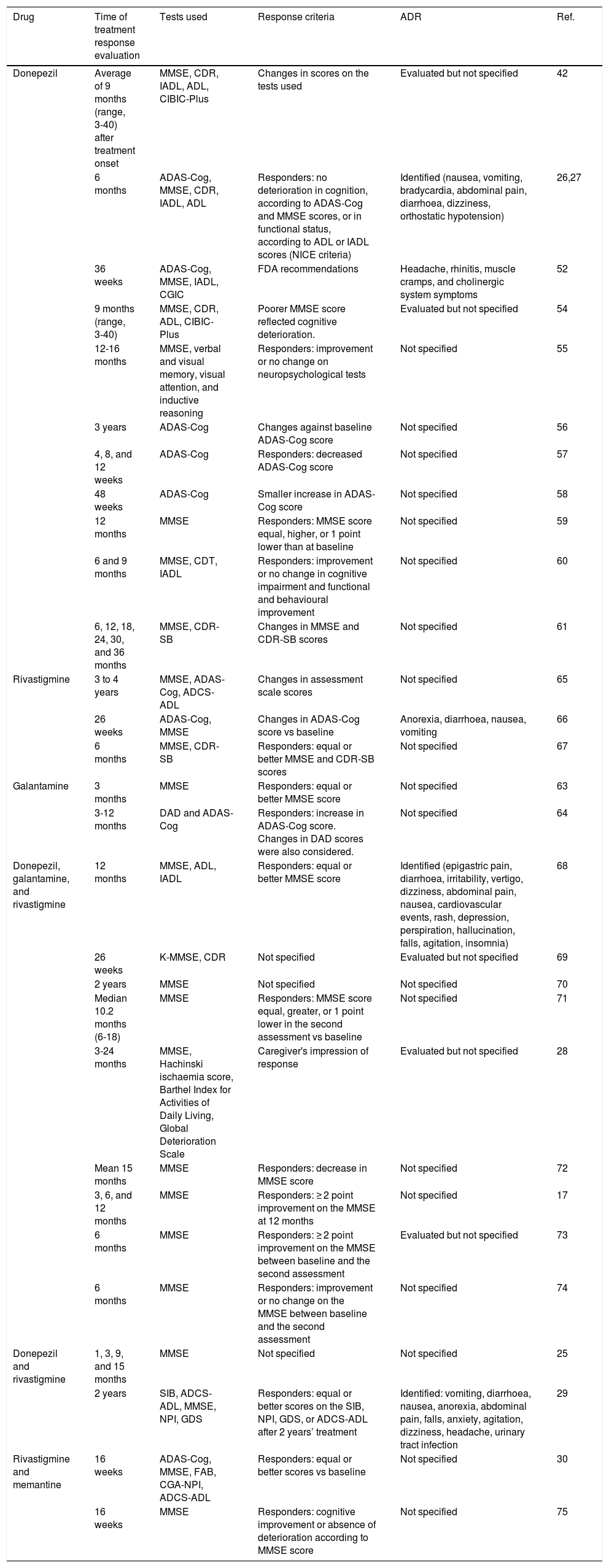

In order to study the association between genetic variants and patients’ response to disease-modifying drugs for AD, we need an established set of clinical parameters and neuropsychological tests to evaluate cognition after treatment onset. The pharmacogenetic studies identified in the literature search use criteria established by the British National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) and by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Some studies based on the NICE recommendations consider “responders” to be those patients not presenting deterioration in cognitive function after at least 6 months of treatment. This definition of treatment response is established by equal or better score on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) or the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive section (ADAS-Cog) scales as compared to baseline values, and an improvement in functional status as measured with the Katz Activities of Daily Living or the Lawton-Brody Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scales.26,27 Most studies focus on MMSE scores, although some use other tests to determine response to disease-modifying drugs (Table 3).28–30

Key aspects of pharmacogenetic studies evaluating clinical response to disease-modifying drugs for Alzheimer disease.

| Drug | Time of treatment response evaluation | Tests used | Response criteria | ADR | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donepezil | Average of 9 months (range, 3-40) after treatment onset | MMSE, CDR, IADL, ADL, CIBIC-Plus | Changes in scores on the tests used | Evaluated but not specified | 42 |

| 6 months | ADAS-Cog, MMSE, CDR, IADL, ADL | Responders: no deterioration in cognition, according to ADAS-Cog and MMSE scores, or in functional status, according to ADL or IADL scores (NICE criteria) | Identified (nausea, vomiting, bradycardia, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, dizziness, orthostatic hypotension) | 26,27 | |

| 36 weeks | ADAS-Cog, MMSE, IADL, CGIC | FDA recommendations | Headache, rhinitis, muscle cramps, and cholinergic system symptoms | 52 | |

| 9 months (range, 3-40) | MMSE, CDR, ADL, CIBIC-Plus | Poorer MMSE score reflected cognitive deterioration. | Evaluated but not specified | 54 | |

| 12-16 months | MMSE, verbal and visual memory, visual attention, and inductive reasoning | Responders: improvement or no change on neuropsychological tests | Not specified | 55 | |

| 3 years | ADAS-Cog | Changes against baseline ADAS-Cog score | Not specified | 56 | |

| 4, 8, and 12 weeks | ADAS-Cog | Responders: decreased ADAS-Cog score | Not specified | 57 | |

| 48 weeks | ADAS-Cog | Smaller increase in ADAS-Cog score | Not specified | 58 | |

| 12 months | MMSE | Responders: MMSE score equal, higher, or 1 point lower than at baseline | Not specified | 59 | |

| 6 and 9 months | MMSE, CDT, IADL | Responders: improvement or no change in cognitive impairment and functional and behavioural improvement | Not specified | 60 | |

| 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months | MMSE, CDR-SB | Changes in MMSE and CDR-SB scores | Not specified | 61 | |

| Rivastigmine | 3 to 4 years | MMSE, ADAS-Cog, ADCS-ADL | Changes in assessment scale scores | Not specified | 65 |

| 26 weeks | ADAS-Cog, MMSE | Changes in ADAS-Cog score vs baseline | Anorexia, diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting | 66 | |

| 6 months | MMSE, CDR-SB | Responders: equal or better MMSE and CDR-SB scores | Not specified | 67 | |

| Galantamine | 3 months | MMSE | Responders: equal or better MMSE score | Not specified | 63 |

| 3-12 months | DAD and ADAS-Cog | Responders: increase in ADAS-Cog score. Changes in DAD scores were also considered. | Not specified | 64 | |

| Donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine | 12 months | MMSE, ADL, IADL | Responders: equal or better MMSE score | Identified (epigastric pain, diarrhoea, irritability, vertigo, dizziness, abdominal pain, nausea, cardiovascular events, rash, depression, perspiration, hallucination, falls, agitation, insomnia) | 68 |

| 26 weeks | K-MMSE, CDR | Not specified | Evaluated but not specified | 69 | |

| 2 years | MMSE | Not specified | Not specified | 70 | |

| Median 10.2 months (6-18) | MMSE | Responders: MMSE score equal, greater, or 1 point lower in the second assessment vs baseline | Not specified | 71 | |

| 3-24 months | MMSE, Hachinski ischaemia score, Barthel Index for Activities of Daily Living, Global Deterioration Scale | Caregiver's impression of response | Evaluated but not specified | 28 | |

| Mean 15 months | MMSE | Responders: decrease in MMSE score | Not specified | 72 | |

| 3, 6, and 12 months | MMSE | Responders: ≥ 2 point improvement on the MMSE at 12 months | Not specified | 17 | |

| 6 months | MMSE | Responders: ≥ 2 point improvement on the MMSE between baseline and the second assessment | Evaluated but not specified | 73 | |

| 6 months | MMSE | Responders: improvement or no change on the MMSE between baseline and the second assessment | Not specified | 74 | |

| Donepezil and rivastigmine | 1, 3, 9, and 15 months | MMSE | Not specified | Not specified | 25 |

| 2 years | SIB, ADCS-ADL, MMSE, NPI, GDS | Responders: equal or better scores on the SIB, NPI, GDS, or ADCS-ADL after 2 years’ treatment | Identified: vomiting, diarrhoea, nausea, anorexia, abdominal pain, falls, anxiety, agitation, dizziness, headache, urinary tract infection | 29 | |

| Rivastigmine and memantine | 16 weeks | ADAS-Cog, MMSE, FAB, CGA-NPI, ADCS-ADL | Responders: equal or better scores vs baseline | Not specified | 30 |

| 16 weeks | MMSE | Responders: cognitive improvement or absence of deterioration according to MMSE score | Not specified | 75 |

ADAS-Cog: Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive section; ADCS-ADL: Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study Activities of Daily Living; ADL: Activities of Daily Living; CDR-SB: Clinical Dementia Rating – Sum of Boxes; CDR: Clinical Dementia Rating; CDT: Clock Drawing Test; CGA-NPI: Caregiver-Administered Neuropsychiatric Inventory; CIBIC-Plus: Clinician's Interview-Based Impression of Change Plus caregiver input; FAB: Frontal Assessment Battery; FDA: United States Food and Drug Administration; GDS: Global Deterioration Scale; IADL: Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; K-MMSE: Korean-language version of the MMSE; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; NICE: UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NPI: Neuropsychiatric Inventory; ADR: adverse drug reaction; SIB: Severe Impairment Battery.

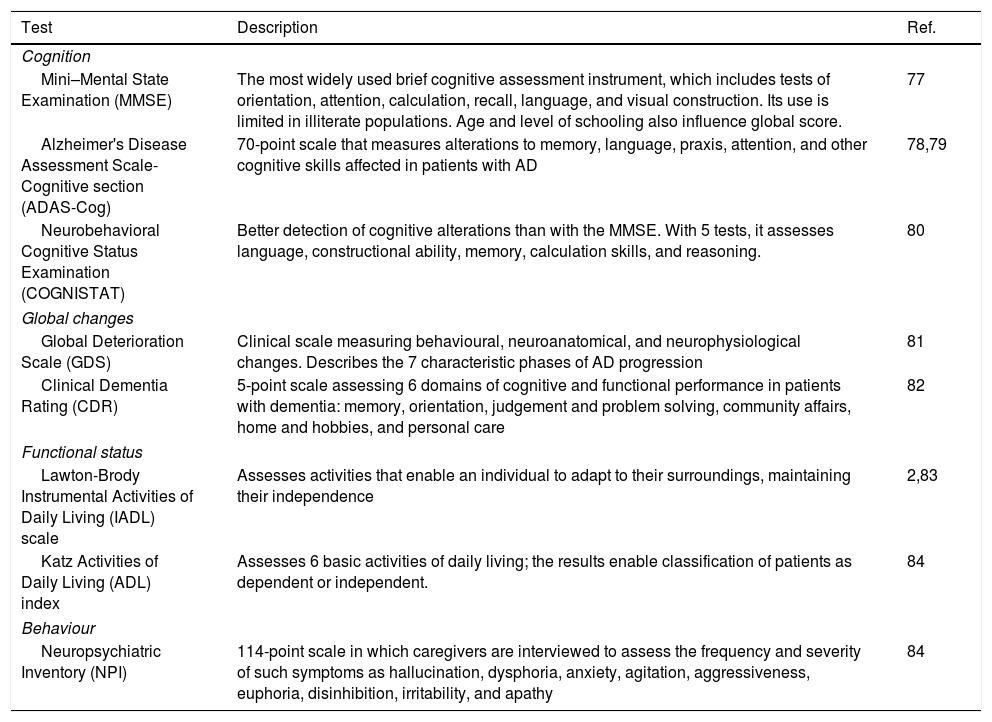

Numerous clinical tests are available for evaluating cognition and functional status2,31; Table 4 shows the main tests used in the pharmacogenetic studies reviewed. To avoid biased results, it is important when testing cognitive function to consider the following issues32:

- -

When using scales to determine AD severity, healthcare professionals should account for any learning difficulties, whether sensory or physical.

- -

Cognitive status assessment should not be based exclusively on patients’ scores on these scales if patients present any disability or linguistic/communication difficulty, are native speakers of a different language, or have a low level of schooling.

- -

MMSE scores are not sufficient for assessing disease severity and treatment response; complementary tests should be performed to assess multiple domains.

Main tests used to assess cognitive impairment and functional status in pharmacogenetic studies into Alzheimer disease.

| Test | Description | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Cognition | ||

| Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE) | The most widely used brief cognitive assessment instrument, which includes tests of orientation, attention, calculation, recall, language, and visual construction. Its use is limited in illiterate populations. Age and level of schooling also influence global score. | 77 |

| Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive section (ADAS-Cog) | 70-point scale that measures alterations to memory, language, praxis, attention, and other cognitive skills affected in patients with AD | 78,79 |

| Neurobehavioral Cognitive Status Examination (COGNISTAT) | Better detection of cognitive alterations than with the MMSE. With 5 tests, it assesses language, constructional ability, memory, calculation skills, and reasoning. | 80 |

| Global changes | ||

| Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) | Clinical scale measuring behavioural, neuroanatomical, and neurophysiological changes. Describes the 7 characteristic phases of AD progression | 81 |

| Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) | 5-point scale assessing 6 domains of cognitive and functional performance in patients with dementia: memory, orientation, judgement and problem solving, community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care | 82 |

| Functional status | ||

| Lawton-Brody Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) scale | Assesses activities that enable an individual to adapt to their surroundings, maintaining their independence | 2,83 |

| Katz Activities of Daily Living (ADL) index | Assesses 6 basic activities of daily living; the results enable classification of patients as dependent or independent. | 84 |

| Behaviour | ||

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) | 114-point scale in which caregivers are interviewed to assess the frequency and severity of such symptoms as hallucination, dysphoria, anxiety, agitation, aggressiveness, euphoria, disinhibition, irritability, and apathy | 84 |

AD: Alzheimer disease.

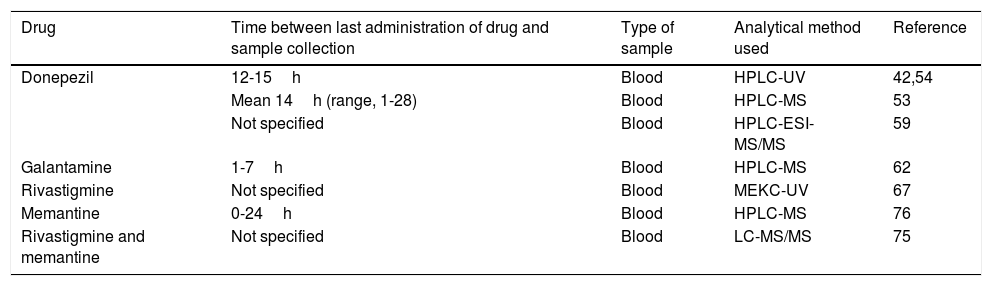

Eight of the 33 pharmacogenetic studies identified determined plasma concentrations of disease-modifying drugs for AD in order to study the association of these values with the gene variants of interest. These studies include both acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine. Table 5 summarises the methodologies followed by these articles.

Specifications of the methods used to determine plasma concentrations of disease-modifying drugs for Alzheimer disease in the pharmacogenetic studies reviewed.

| Drug | Time between last administration of drug and sample collection | Type of sample | Analytical method used | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donepezil | 12-15h | Blood | HPLC-UV | 42,54 |

| Mean 14h (range, 1-28) | Blood | HPLC-MS | 53 | |

| Not specified | Blood | HPLC-ESI-MS/MS | 59 | |

| Galantamine | 1-7h | Blood | HPLC-MS | 62 |

| Rivastigmine | Not specified | Blood | MEKC-UV | 67 |

| Memantine | 0-24h | Blood | HPLC-MS | 76 |

| Rivastigmine and memantine | Not specified | Blood | LC-MS/MS | 75 |

HPLC–ESI-MS/MS: high-performance liquid chromatography/electrospray ionisation tandem mass spectrometry; HPLC–MS: high-performance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry; HPLC–UV: high-performance liquid chromatography and ultraviolet detection; LC–MS/MS: liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry; MEKC-UV: micellar electrokinetic capillary chromatography with ultraviolet detection.

Plasma concentrations of disease-modifying drugs for AD are determined at steady state, which occurs at 4-5 half-lives.33 The reported half-life of donepezil (70-80hours) is significantly longer than those of other acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (0.3-12hours).34–36 Memantine also has a long half-life, at 60-80hours.37 Given these half-life values, we can expect a steady state to be reached by a maximum of 17 days after the administration of these drugs.

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry is the technique of choice in pharmacogenetic studies quantifying plasma levels of disease-modifying drugs for dementia. The advantages of this method are its sensitivity, specificity, the speed of testing, the small plasma volumes needed (250-500μL), and the ability to simultaneously quantify multiple drugs and some of their metabolites, in some cases.38–41

Important considerations in pharmacogenetic studies into Alzheimer diseaseOn account of the complexity of AD, pharmacogenetic studies also assess patients’ physical health, the presence of other diseases and concomitant treatments,42 and treatment adherence.26,27 These factors clearly have an important impact on treatment response and on plasma drug concentrations; therefore, they may interfere in the analysis of associations between these parameters and pharmacogenetic variants.

Studies evaluating treatment adherence in patients with AD report compliance ranging from 34% to 94%; the large disparities reported may be explained by the use of techniques supporting treatment adherence, such as a primary caregiver taking responsibility for administering the drugs.43 This variability may reflect a bias in the evaluation of treatment response. Numerous methods are available for evaluating treatment adherence,44 and using such measures would contribute to the reliability of the results.

Several articles report that approximately 50% of the elderly population studied present one or more chronic diseases.45,46 This may influence the evaluation of treatment response, as comorbidity is reported to complicate the clinical course of AD, for example by accelerating cognitive impairment and functional loss. Conditions affecting cognitive function in patients with dementia include heart failure, coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.45,47

According to one study, primary care patients with dementia present an average of 2.4 chronic diseases and receive 5.1 different medications.48 Polymedication may strongly influence treatment response and concentrations of disease-modifying drugs for AD, particularly those metabolised by cytochromes, which are easily inhibited or induced by other drugs. However, acetylcholinesterase antagonists and the NMDA receptor antagonist memantine are thought to have little potential for drug-drug interactions.49 Despite this, recording concomitant treatments may be relevant in studies into AD drugs, as they may explain some variation in treatment response and the presence of adverse reactions.45

Immunotherapy with monoclonal antibodiesNovel approaches to AD treatment are based on the amyloid hypothesis, and involve the use of monoclonal antibodies that recognise different epitopes of Aβ peptide and display selective binding.50 Clinical trials with bapineuzumab, ponezumab, solanezumab, and gantenerumab have been suspended, while aducanumab is currently in phase III. This human antibody selectively targets Aβ aggregates (including soluble oligomers and insoluble fibrils), reducing Aβ plaques and slowing clinical progression in patients with mild or prodromal AD. In the phase Ib trial of aducanumab, which included 196 patients with AD, an important consideration was patient selection: presence of Aβ deposits had to be confirmed by positron emission tomography molecular imaging. The safety and tolerability of the antibody were acceptable, but an adverse reaction associated with elimination of Aβ was observed; this reaction was dose-dependent and occurred more frequently in carriers of the ɛ4 allele of APOE than in non-carriers. However, as this trial did not find sufficient efficacy to meet the exploratory clinical criteria, cognitive findings should be interpreted with caution.51

ConclusionsFew pharmacogenetic studies have been performed on drugs for AD. However, some studies report an association between variants of genes including CYP2D6, ABCB1, and BCHE and treatment response or plasma concentration of disease-modifying drugs for AD.

Performing this type of research in other populations may contribute further data to assist regulators in establishing more precise pharmacogenetic recommendations for the treatment of AD. For example, CYP2D6 is a pharmacogenetic biomarker recommended for multiple drugs; in AD, it may assist in the safe, effective use of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, despite the fact that its use in this context remains under study. In this context, pharmacogenetics is a promising tool for identifying novel, safer, more efficacious treatments for AD, as well as supporting the development of drugs currently being researched.

None of the drugs developed for stopping the production or aggregation of Aβ or for promoting its elimination have been shown to be efficacious in the phase III clinical trials performed to date. Therefore, research into new therapeutic targets is needed, particularly in the preclinical stage of the disease.

Identifying pharmacogenetic biomarkers that may predict patient response to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine may contribute to therapeutic decision-making for these patients. In a context as complex as ageing, characterised by polymedication and comorbidity, the presence of pleiotropic effects may play a decisive role.

FundingThis project was funded by the Mexican National Council for Science and Technology (CONACYT). This article is part of CONACYT's Scientific Development Project to Address National Issues (proposal no. 3099; 2016), Dr Tirso Zúñiga Santamaría's postdoctorate fellowship (funded by CONACYT), and the grant for doctoral studies awarded to Ingrid Fricke-Galindo (grant no. CONACYT#369708).

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Zúñiga Santamaría T, Yescas Gómez P, Fricke Galindo I, González González M, Ortega Vázquez A, López López M. Estudios farmacogenéticos en la enfermedad de Alzheimer. Neurología. 2022;37:287–303.