Amyloidosis is caused by extracellular deposition of insoluble fibrillary amyloid proteins in numerous organs and tissues. The term ‘amyloid’ was adopted by Rudolph Virchow in 1854 to refer to tissue deposits of this type. Depending on the biochemical characteristics of the amyloid precursor protein, we can distinguish between multiple forms of amyloidosis with different clinical patterns.1–3 In developed countries, the most common form of amyloidosis is primary or AL amyloidosis, characterised by the absence of other pre-existing or concurrent diseases. These patients present monoclonal plasma cells in bone marrow which constantly produce fragments of light chains. Lambda light chains predominate over kappa light chains in a ratio of 2:1.

Systemic signs and symptoms are extremely varied and include kidney disease (proteinuria or nephrotic syndrome), congestive heart failure, oedema, purpura, macroglossia, hepatomegaly with or without splenomegaly, pulmonary manifestations, motor and sensory peripheral neuropathy, and/or autonomic neuropathy.4–6

Vascular impairment resulting from amyloidosis includes tissue infarctions caused by vascular amyloid infiltration, such as jaw claudication7 or ischaemic heart disease. It is associated with the presence of intramural deposits of AL amyloid protein.8 Despite the clinical heterogeneity of the disease, descriptions of vascular involvement in the central nervous system are rare, and most correspond to ischaemic stroke.

We present the case of a patient who suffered 2 intracranial haemorrhages in the months after being diagnosed with primary amyloidosis; the second was fatal.

The patient was a male aged 78 years with a history of arterial hypertension (AHT) and nephrotic syndrome in the preceding 2 years. He was admitted on an emergency basis due to severe oedema of the legs and dyspnoea with moderate effort. Renal function deteriorated rapidly and he required emergency haemodialysis. Ten days later he experienced left facial paralysis, abolition of vibratory sensation in the lower limbs, and ataxic gait. There were no signs of vascular changes in either the brain MRI or the transcranial and supra-aortic trunk Doppler studies. Immunoelectrophoresis of serum and urine revealed IgG-lambda monoclonal gammopathy. Renal biopsy showed massive diffuse and perivascular deposits in the glomerular capillary and the interstitium. Deposits tested positive for C3 and lambda light chains according to a Congo red stain and direct immunofluorescence test. This confirmed the diagnosis of primary renal amyloidosis. Furthermore, transthoracic echocardiogram showed a marked increase in parietal wall thickness and a granular appearance that was compatible with myocardial amyloid deposition. Lastly, bone marrow biopsy calculated the level of pathological plasmablasts at 7%.

Once the patient had been diagnosed with primary amyloidosis with renal, cardiac, and peripheral nervous system involvement, doctors began treatment with melphalan and prednisone. As two cycles of treatment did not produce a response, second-line therapy with bortezomib was started.

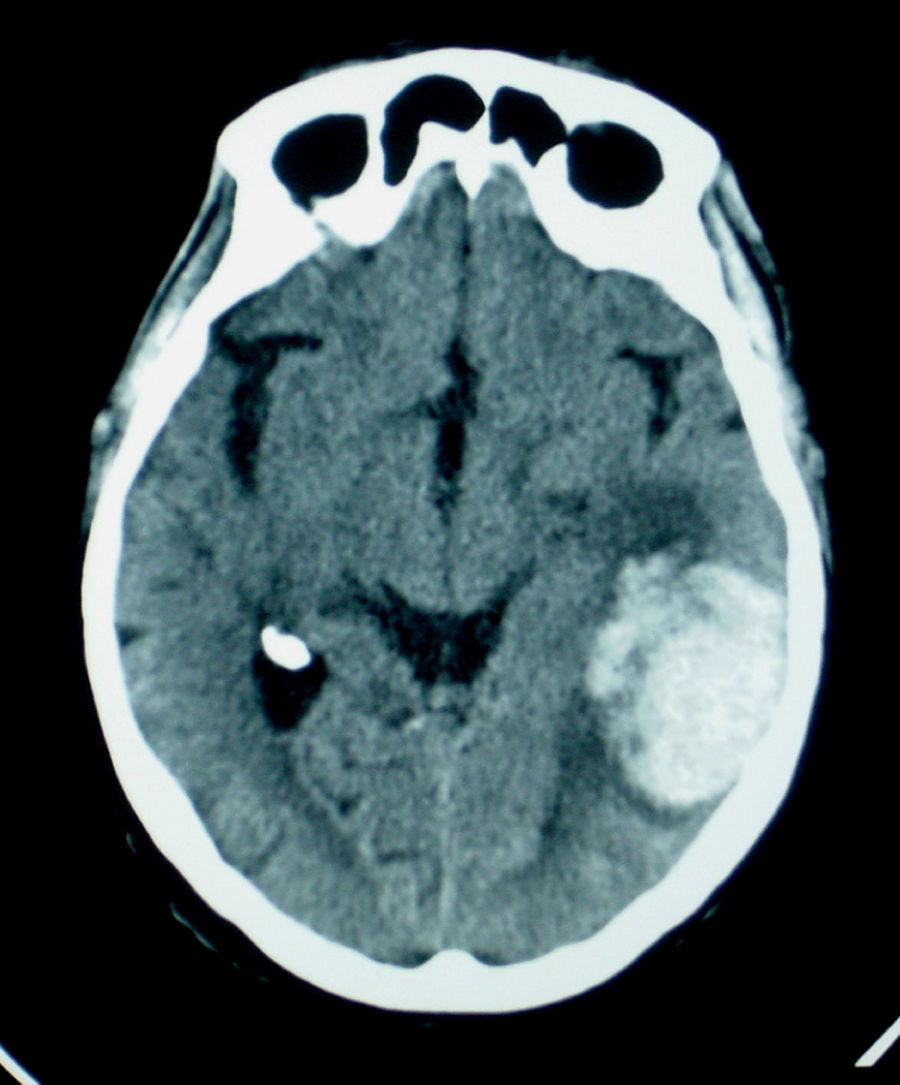

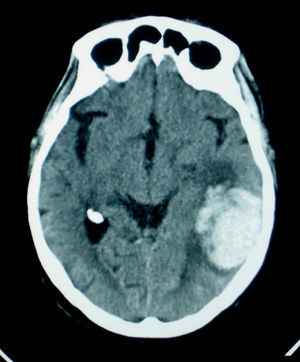

The patient presented sudden-onset language disturbance and right-side hemiparesis 10 weeks after first being admitted. A cranial computed tomography (CT) study performed a few hours after symptom onset revealed a left intraparenchymal cortical–subcortical temporoparietal haemorrhage (Fig. 1). The patient's condition subsequently improved and he was discharged with moderate non-fluent aphasia.

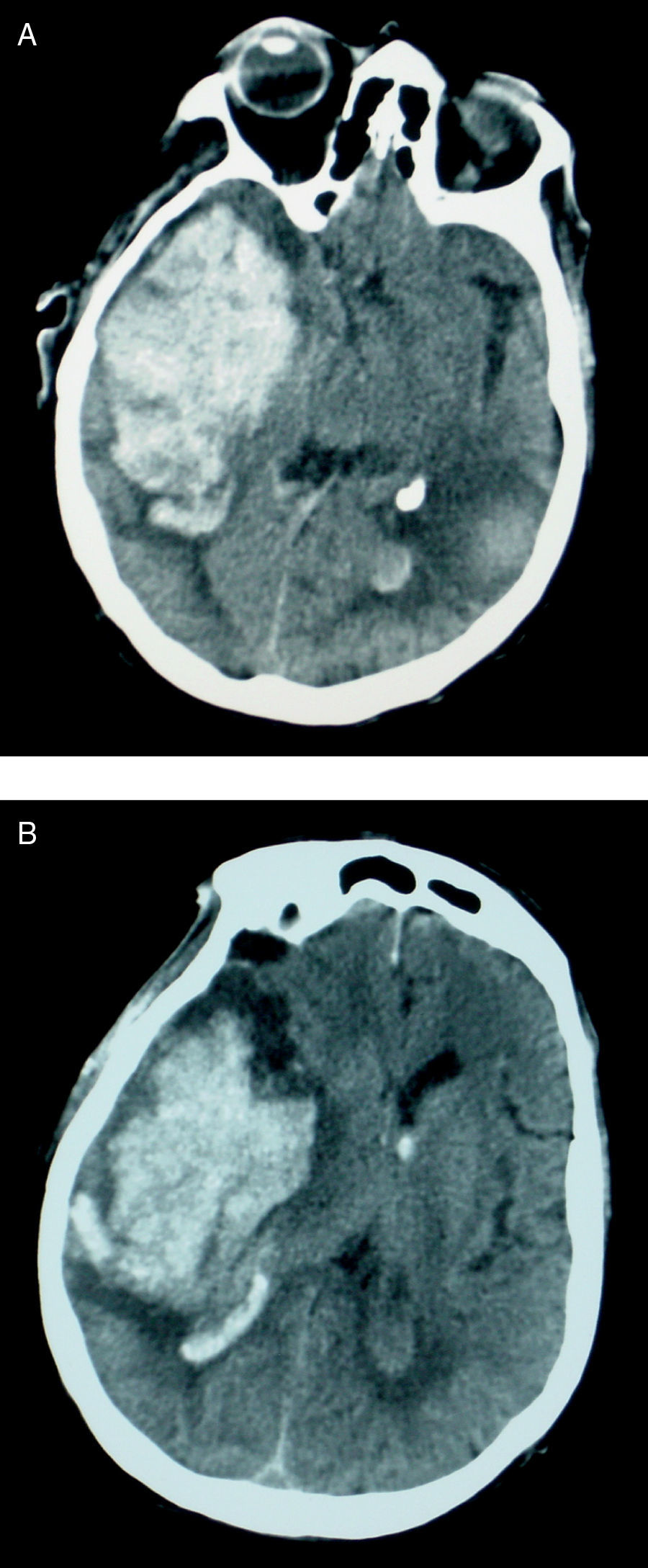

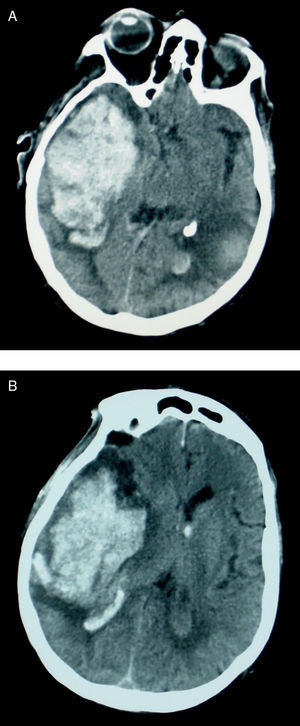

A month later, he visited once more due to acute decrease in level of consciousness. The patient was comatose upon examination with left hemiplegia and right mydriasis with a non-reactive pupil. A brain CT performed approximately 1 hour later showed an extensive right cortical temporoparietal haematoma with a mass effect and bleeding into lateral ventricles (Fig. 2). The patient died 48hours after admission on this occasion.

Brain CT. (A) Axial slice. Right acute cortical temporal haematoma and resolving left parietal haematoma and (B) axial slice at the level of the lateral ventricles showing an extensive acute right cortical–subcortical parietal haematoma with a mass effect and bleeding into the lateral ventricles.

Primary or AL amyloidosis is a plasma cell dyscrasia that mainly presents in elderly males. The yearly incidence rate is 8 to 9 new cases per million inhabitants per year. Prognosis is poor, with a mean survival time of approximately 2 years that essentially depends on the associated syndrome. When cardiac amyloid deposits are present and cause symptoms, the mean survival time is only 8 months.4,8 In general, the involvement pattern of primary amyloidosis is multi-systemic, with a wide variety of clinical manifestations. Although a patient's history and clinical manifestations may suggest amyloidosis, diagnosis can only be confirmed by a tissue biopsy.

Neurological symptoms appear in 17% of all cases, mainly in the form of sensory, motor, or autonomic peripheral neuropathy due to amyloid deposition. Compression of peripheral nerves, especially the median nerve in the carpal tunnel, may cause more localised sensory alterations.

Regarding cerebrovascular disease in the context of systemic amyloidosis, both TIAs and established ischaemic strokes have occasionally been described as the initial manifestations of amyloidosis. Strokes are generally cardioembolic (70%) and related to myocardial or valvular amyloid deposition.9,10

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), characterised by the deposition of congophilic material in small and medium-sized blood vessels in the brain and leptomeninges, is an important cause of primary lobar intracerebral haemorrhage in elderly patients, especially those with associated cognitive impairment. This is due to rupture of the vascular walls as a result of amyloid deposition.11,12 However, haemorrhages associated with CAA rarely reach the ventricular system, which occurred in the second event suffered by the patient we present here. When haemorrhages recur (rate of 21% in 2 years), they tend to affect the same lobe as before.13

The literature contains descriptions of gastrointestinal and alveolar haemorrhages, haematuria, etc. in patients with primary amyloidosis. These events are fundamentally related to vascular infiltration of amyloid material, causing vessels to become more fragile, as in CAA14; gastrointestinal haemorrhages may be due to ulceration, oesophageal varices, or amyloidomas. While we did not locate any descriptions of haemorrhagic stroke in primary amyloidosis, we believe that the underlying histopathological description would match that of other haemorrhages: vascular infiltration by amyloid.

Although both CAA and primary amyloidosis may be present in the same patient, the association can only be confirmed by an anatomical pathology study of cerebral blood vessels, which was not performed.

Regarding whether bortezomib may have triggered the haemorrhages, the most recent reviews of this drug indicate that it is generally well tolerated and has a good safety profile. Although thrombocytopenia is listed as one of its side effects, it is not typically associated with severe complications such as haemorrhages.15

With this case description, we would like to state that intracerebral haemorrhage may constitute yet another clinical manifestation on the long list of primary amyloidosis symptoms. As occurred in our case, it may have devastating consequences.