Door-to-needle time (DNT) has been established as the main indicator in code stroke protocols. According to the 2018 guidelines of the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association, DNT should be less than 45minuts; therefore, effective and revised pre-admission and in-hospital protocols are required.

MethodWe analysed organisational changes made between 2011 and 2019 and their influence on DNT and the clinical progression of patients treated with fibrinolysis. We collected data from our centre, stored and monitored under the Master Plan for Cerebrovascular Disease of the regional government of Catalonia. Among other measures, we analysed the differences between years and differences derived from the implementation of the Helsinki model.

ResultsThe study included 447 patients, and we observed significant differences in DNT between different years. Pre-hospital code stroke activation, recorded in 315 cases (70.5%), reduced DNT by a median of 14minutes. However, the linear regression model only showed an inversely proportional relationship between the adoption of the Helsinki code stroke model and DNT (beta coefficient, –0.42; P<.001). The removal of vascular neurologists after the adoption of the Helsinki model increased DNT and the 90-day mortality rate.

ConclusionDNT is influenced by the organisational model. In our sample, the application of the Helsinki model, the role of the lead vascular neurologist, and notification of code stroke by pre-hospital emergency services are key factors for the reduction of DNT and the clinical improvement of the patient.

El tiempo puerta aguja (TPA) es el principal indicador del proceso del código ictus (CI). Según la guía de 2018 de la American Heart Association/American Stroke Association el objetivo TPA debe ser inferior a 45 minutos. Para conseguirlo son necesarios protocolos eficaces y revisados de actuación extrahospitalaria e intrahospitalaria.

MétodoAnalizamos la influencia de cambios organizativos entre 2011al 2019 en el TPA y en la evolución clínica de los pacientes tratados con fibrinólisis. Utilizamos los datos de nuestro centro monitorizados y custodiados por elPla Director en l’àmbit de la Malaltia Vascular Cerebral de la Generalitat de Catalunya. Entre otras medidas se han analizado las diferencias entre los años y las derivadas de la implantación del modelo Helsinki.

ResultadosSe estudiaron 447 pacientes, existiendo diferencias estadísticamente significativas en el TPA entre los diferentes años. La activación del CI de forma extrahospitalaria en 315 (70,5%) pacientes redujo el TPA una mediana de 14 minutos. Sin embargo, el modelo de regresión lineal sólo evidenció una relación inversamente proporcional entre la adopción del modelo de CI Helsinki (MH) y el TPA (coeficiente beta −0,42; p<0,001). La eliminación de la figura del neurólogo vascular tras la adopción del MH empeoró el TPA y la mortalidad a los 90 días.

ConclusiónEl modelo organizativo influye en el TPA, siendo en nuestra muestra la aplicación del MH, la existencia de la figura del neurólogo vascular referente y la prenotificación del CI factores claves para la reducción del TPA y la mejora clínica del paciente.

The World Health Organization describes ischaemic stroke as the leading cause of death in men and the third in women. This is one of the most fatal diseases, together with cancer and cardiovascular diseases.1 In 2017, 26 937 people died due to cerebrovascular disease.2 First with intravenous fibrinolysis, 25 years ago,3 and later with thrombectomy, 5 years ago,4 together with the development of stroke units,5 great advances have been made in the care of patients with ischaemic stroke in the acute phase. In both reperfusion therapies, early administration is the main prognostic factor for functional recovery.6,7 In the case of intravenous fibrinolysis, door-to-needle time (DNT) has emerged as a process indicator in the care of patients meeting criteria for code stroke (CS) activation in the emergency department. According to the 2018 guidelines of the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association, DNT should be less than 45minutes.8 Successful experiences include that published by Meretoja et al.9–11 (Helsinki stroke model), who found that after the application of 12 measures including the participation of the emergency department, prehospital notification, fast transfer to the computed tomography (CT) room, and decreasing the delay in the interpretation of CT studies, DNT significantly decreased to below 30minutes.9–11 Previously, in 2006, the Spanish Society of Neurology’s Stroke Study Group described key aspects in the emergency care of patients meeting criteria for CS activation, such as the presence of a stroke team coordinated by a neurologist specialising in stroke, or the recommendation to establish an on-site on-call neurology service; these measures are confirmed in the study group’s 2010 Stroke Health Care Plan.12,13

We analyse the influence of these changes on the DNT in the care of patients with acute ischaemic stroke and on the clinical progression of these patients at a university hospital considered a reference centre in stroke care, which has been equipped with a stroke unit since 2006.

Material and methodsWe included retrospective data from consecutive patients meeting criteria for CS activation and attended at our centre and treated with intravenous fibrinolysis according to the neurologist’s clinical judgement, in accordance with national and international guidelines.8,14 Cases of stroke of unknown time of onset were treated with intravenous fibrinolysis for compassionate use, accounting for stroke severity, the presence of intracranial large-vessel occlusion, and the absence of signs of acute ischaemia. All patients were prospectively recorded in the online intravenous fibrinolysis registry of the Catalan regional government’s master plan for cerebrovascular disease15–17 during the period between 2011 and 2019, inclusive. This information was stored under the Master Plan until it was returned to the centre on 30 April 2020. The registry has been exhaustively monitored on a regular basis. An external auditing process is in place to avoid inclusion bias. All hospitals providing stroke care in Catalonia are sent a quarterly report.17

The registry includes data on the patients’ clinical characteristics, DNT, and progression at 3 months. We determined the score on the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) using a structured interview.

The registry meets all the legal requirements for the protection of personal data. All patients signed an informed consent form.17

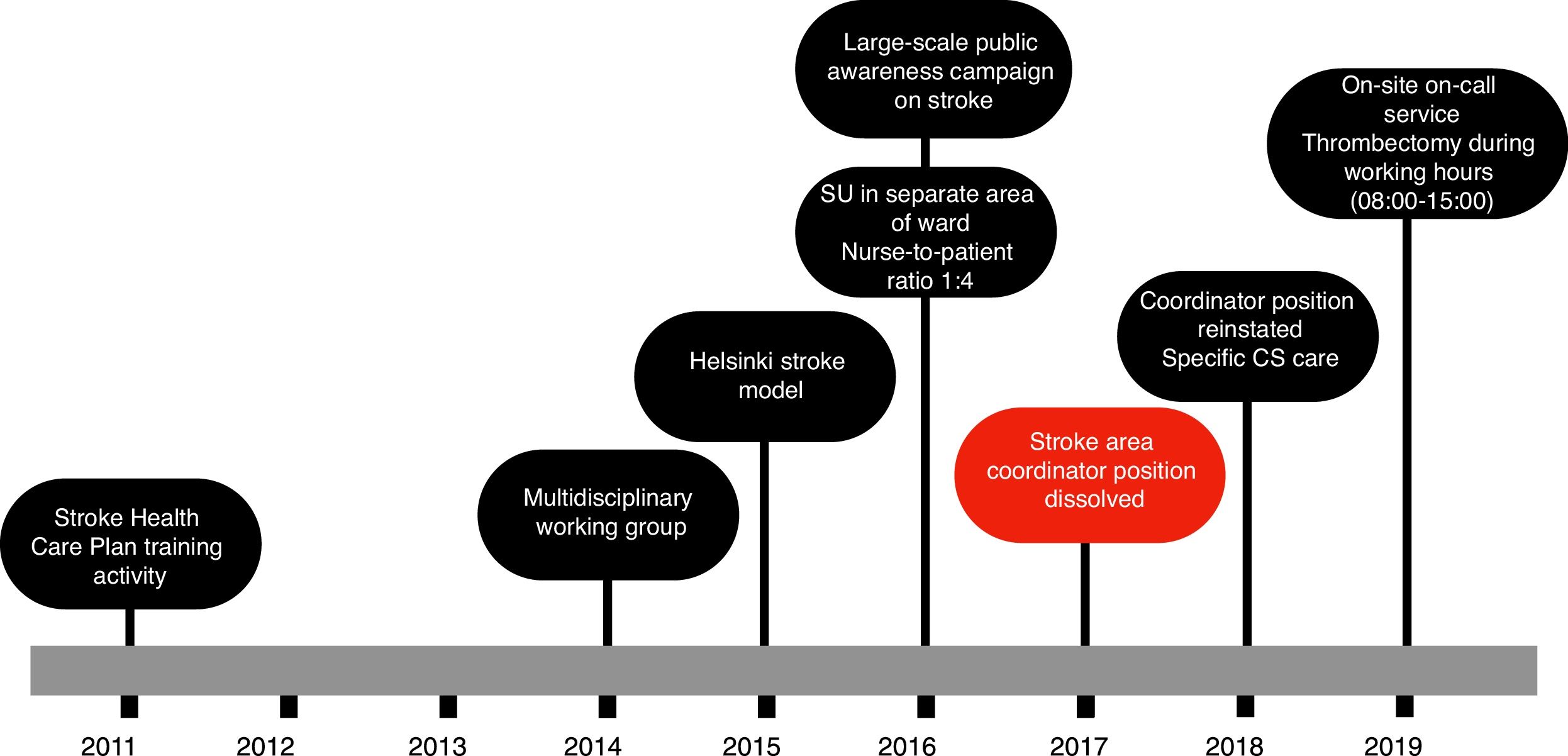

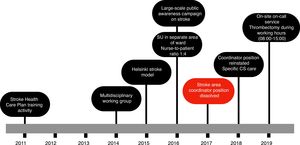

Fig. 1 shows the actions taken between the patient’s arrival at the hospital and administration of intravenous fibrinolysis according to our current in-hospital protocol. In 2014, a multidisciplinary CS team was established, including members of the emergency and radiology departments, as well as the medical emergency services. We adopted the Helsinki stroke model from 2015, except in 2017, when the position of cerebrovascular area coordinator was dissolved. In 2016, a stroke unit was created in the semi-critical care unit, separated from the main ward, with sufficient nursing staff to guarantee a nurse-to-patient ratio of 1:4. Finally, in 2019, on-site on-call neurology shifts were introduced, and the hospital began to offer intravenous treatment.

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistics software, version 20.0.

We studied the differences between patients according to the year of treatment. Categorical variables were compared using the Pearson chi-square test. Numerical variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test and the ANOVA test for independent samples. We analysed the variables associated with DNT. Variables presenting a statistically significant association were included in the multivariate analysis using a linear regression model. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P<.05.

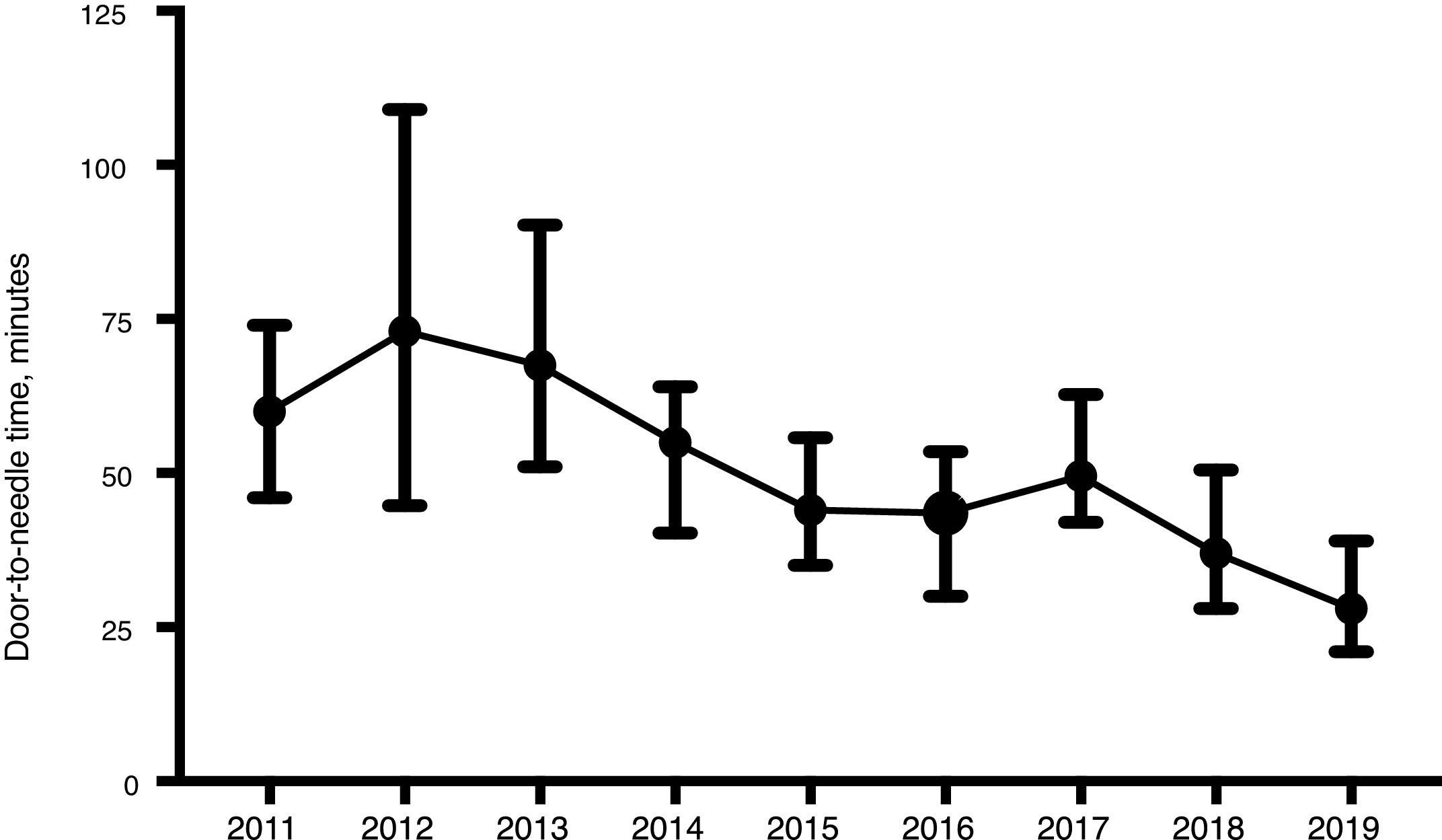

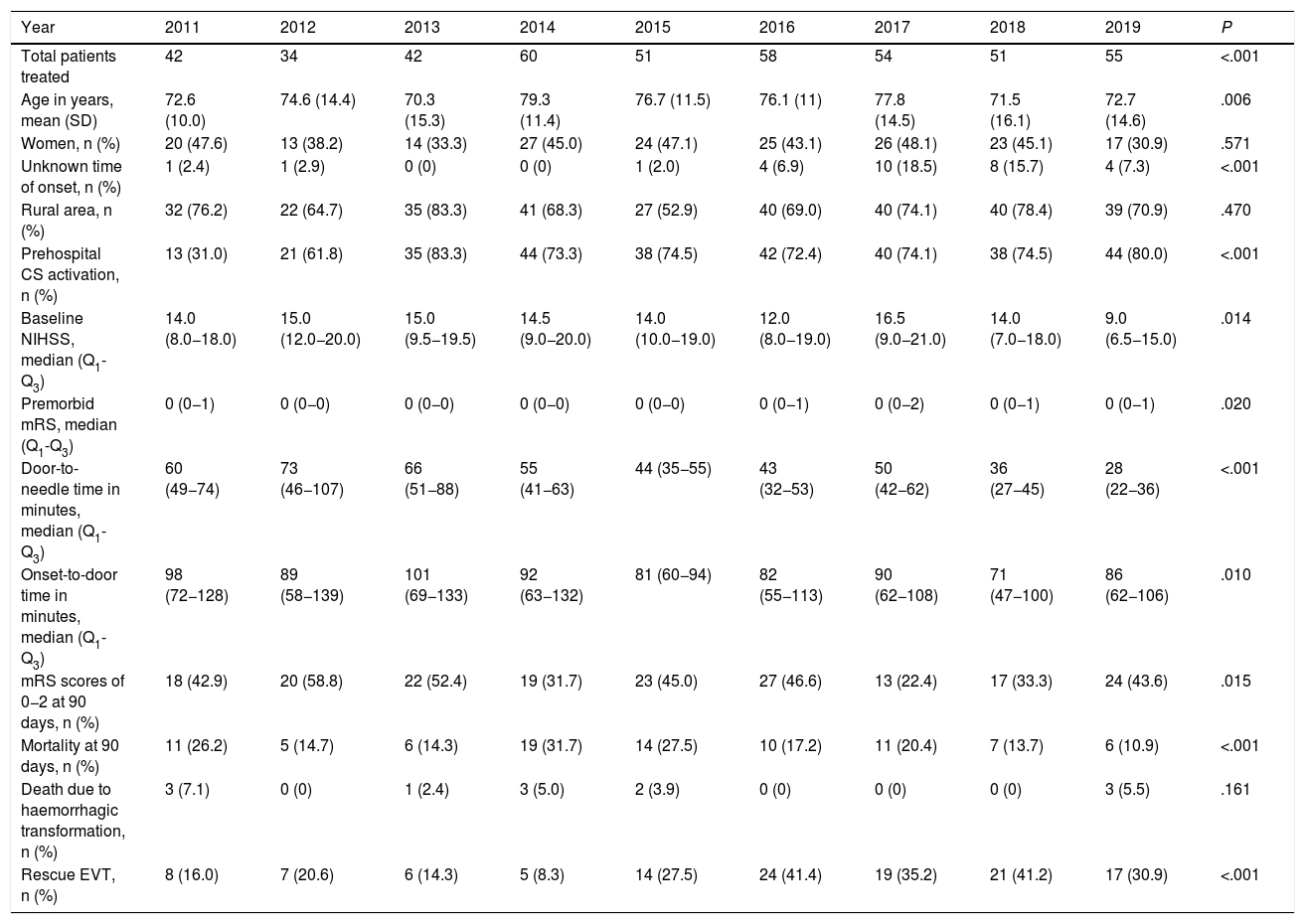

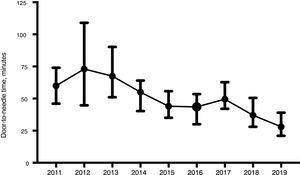

ResultsWe included a total of 447 individuals. The mean age was 74.9 years (standard deviation [SD]: 13.5 years). We observed a significant increase in the number of patients treated from 2014. Our sample included predominantly men (258, 57.7%). Only 29 (6.5%) patients were treated for compassionate use despite the precise time of symptom onset being unknown. Most patients (316, 70.7%) lived in rural areas. Prehospital CS was activated in 315 cases (70.5%). As shown in Table 1, statistically significant differences were observed between years for almost all the variables analysed. The DNT was significantly shorter during the years when the Helsinki stroke model was applied (Fig. 2). The mortality rate was also lower during those years, as opposed to in 2017, when the model was not applied. The proportion of patients receiving intravascular treatment also increased significantly from 2015, whereas onset-to-door time decreased. The mean age of treated patients decreased significantly in the last 2 years, as did stroke severity (NIHSS score) in the last year. However, differences between years in the percentage of women treated and in the proportion of patients from rural areas were not statistically significant.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of patients treated with intravenous fibrinolysis during the study period.

| Year | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients treated | 42 | 34 | 42 | 60 | 51 | 58 | 54 | 51 | 55 | <.001 |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 72.6 (10.0) | 74.6 (14.4) | 70.3 (15.3) | 79.3 (11.4) | 76.7 (11.5) | 76.1 (11) | 77.8 (14.5) | 71.5 (16.1) | 72.7 (14.6) | .006 |

| Women, n (%) | 20 (47.6) | 13 (38.2) | 14 (33.3) | 27 (45.0) | 24 (47.1) | 25 (43.1) | 26 (48.1) | 23 (45.1) | 17 (30.9) | .571 |

| Unknown time of onset, n (%) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.0) | 4 (6.9) | 10 (18.5) | 8 (15.7) | 4 (7.3) | <.001 |

| Rural area, n (%) | 32 (76.2) | 22 (64.7) | 35 (83.3) | 41 (68.3) | 27 (52.9) | 40 (69.0) | 40 (74.1) | 40 (78.4) | 39 (70.9) | .470 |

| Prehospital CS activation, n (%) | 13 (31.0) | 21 (61.8) | 35 (83.3) | 44 (73.3) | 38 (74.5) | 42 (72.4) | 40 (74.1) | 38 (74.5) | 44 (80.0) | <.001 |

| Baseline NIHSS, median (Q1-Q3) | 14.0 (8.0−18.0) | 15.0 (12.0−20.0) | 15.0 (9.5−19.5) | 14.5 (9.0−20.0) | 14.0 (10.0−19.0) | 12.0 (8.0−19.0) | 16.5 (9.0−21.0) | 14.0 (7.0−18.0) | 9.0 (6.5−15.0) | .014 |

| Premorbid mRS, median (Q1-Q3) | 0 (0−1) | 0 (0−0) | 0 (0−0) | 0 (0−0) | 0 (0−0) | 0 (0−1) | 0 (0−2) | 0 (0−1) | 0 (0−1) | .020 |

| Door-to-needle time in minutes, median (Q1-Q3) | 60 (49−74) | 73 (46−107) | 66 (51−88) | 55 (41−63) | 44 (35−55) | 43 (32−53) | 50 (42−62) | 36 (27−45) | 28 (22−36) | <.001 |

| Onset-to-door time in minutes, median (Q1-Q3) | 98 (72−128) | 89 (58−139) | 101 (69−133) | 92 (63−132) | 81 (60−94) | 82 (55−113) | 90 (62−108) | 71 (47−100) | 86 (62−106) | .010 |

| mRS scores of 0−2 at 90 days, n (%) | 18 (42.9) | 20 (58.8) | 22 (52.4) | 19 (31.7) | 23 (45.0) | 27 (46.6) | 13 (22.4) | 17 (33.3) | 24 (43.6) | .015 |

| Mortality at 90 days, n (%) | 11 (26.2) | 5 (14.7) | 6 (14.3) | 19 (31.7) | 14 (27.5) | 10 (17.2) | 11 (20.4) | 7 (13.7) | 6 (10.9) | <.001 |

| Death due to haemorrhagic transformation, n (%) | 3 (7.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.4) | 3 (5.0) | 2 (3.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (5.5) | .161 |

| Rescue EVT, n (%) | 8 (16.0) | 7 (20.6) | 6 (14.3) | 5 (8.3) | 14 (27.5) | 24 (41.4) | 19 (35.2) | 21 (41.2) | 17 (30.9) | <.001 |

CS, code stroke; EVT, endovascular treatment; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; SD, standard deviation.

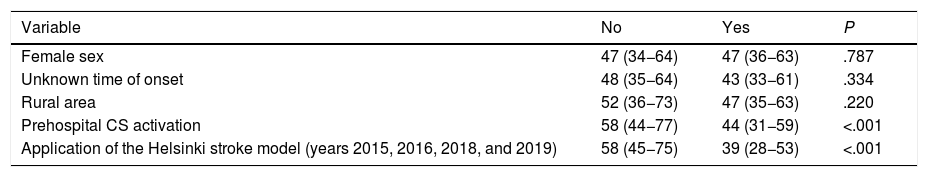

We performed a statistical analysis of the factors associated with DNT (Table 2). Prehospital CS activation and having been treated in one of the years when the Helsinki stroke model was applied were significantly associated with a shorter DNT. We observed no significant association with age (Spearman coefficient, rho=–0.037; P=.458), NIHSS score (rho=0.042; P=.394), or mRS score (rho=0.016; P=.745); however, onset-to-door time (rho=0.319; P=.006) did show an association, with a directly proportional relationship between DNT and onset-to-door time. The linear regression model only identified an inversely proportional relationship between the Helsinki stroke model and DNT (beta coefficient: −0.42; 95% confidence interval: −23.75 to −14.57; P<.001).

Analysis of variables associated with door-to-needle time.

| Variable | No | Yes | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 47 (34−64) | 47 (36−63) | .787 |

| Unknown time of onset | 48 (35−64) | 43 (33−61) | .334 |

| Rural area | 52 (36−73) | 47 (35−63) | .220 |

| Prehospital CS activation | 58 (44−77) | 44 (31−59) | <.001 |

| Application of the Helsinki stroke model (years 2015, 2016, 2018, and 2019) | 58 (45−75) | 39 (28−53) | <.001 |

CS, code stroke.

We present the results of a prospective study of consecutive patients with suspected acute ischaemic stroke and treated with intravenous fibrinolysis. Our findings suggest that organisational changes have an impact on the main process indicator, DNT. Furthermore, and in parallel to the consequences for DNT, the clinical progression of these patients also changed. In our 9-year cohort study, the main independent factor associated with DNT was the application of the Helsinki stroke model and the presence of a neurologist coordinating the stroke team. The Helsinki stroke model is based on the development of the stroke, both from the pre-hospital and the in-hospital perspective.9–11 Therefore, a key role is played both by prehospital notification by the prehospital emergency services and the early transfer of patients to the radiology unit or the intravenous administration of a fibrinolytic bolus in the same room.10 The coordinator is the reference professional responsible for updating the protocols and procedures of the cerebrovascular disease area, calling periodic meetings for professionals participating in CS care, and analysing and distributing the data on CS care and other aspects related to the care of patients with stroke. In our setting, the creation of a multidisciplinary group led by vascular neurologists and involving the collaboration of the emergency department staff, prehospital emergency services, and radiology professionals (who enabled us to critically review and update the progression of stroke) already led to improvements in DNT in 2014, even before the application of the Helsinki stroke model in 2015. Later, the availability of a stroke unit in line with the national and international recommendations,12,13,18 alongside the reduction in DNT, may have played a key role in reducing mortality. Finally, the availability of an on-site on-call neurology service and the review of the action protocols at treatment onset also helped in the optimisation of DNT. We should highlight the increase in DNT and mortality rates in 2017, which coincided with an organisational change that led to the elimination of the position of cerebrovascular disease area coordinator. This further demonstrates the relevance of the neurovascular area being led by an experienced professional, to ensure both the coordination of the CS process and the monitoring of the process indicators necessary for decision-making, as recommended by the Spanish Society of Neurology’s Stroke Study Group.12,13 Furthermore, it shows the relevance of DNT as a process indicator associated with clinical outcomes.7,9

The presence of an optimal organisational model was the only independent predictor of DNT. As the main challenge, we should highlight the improvement in the care of the patients with stroke for whom prehospital CS was not activated. With the application of the Helsinki stroke model, prehospital CS activation is associated with a prehospital notification that increases the preparedness of the professionals involved in the care of patients, which has a positive impact on DNT.10,11,19,20 However, this does not occur with in-hospital activation. Our findings support the need to implement specific measures to reduce DNT in this group of patients. In our series, unlike others,19,20 we observed a direct relationship between onset-to-door time and DNT. This fact may be explained by the application of the Helsinki stroke model and the increased awareness of the disease among primary care physicians and the general population, which would also contribute to a reduction in onset-to-door time and DNT.

Our study presents some limitations. A larger sample size may further favour the extrapolation of our results and avoid differences between years that may be attributed to chance. Furthermore, specific situations in certain years are not easy to explain. For example, in 2019, the baseline NIHSS score was significantly lower than in the remaining years, and the frequency of prehospital CS activation was considerably lower in 2011 than in 2012.

In conclusion, the organisational model is the main factor influencing DNT, the main process indicator of CS. In this sense, the Helsinki stroke model together with the availability of an on-call neurology service on site, a stroke unit organised according to international criteria, and a stroke area coordinator with experience in neurovascular disease constitute the best scenario to achieve an optimal DNT with good clinical outcomes. Any change in this paradigm translates to worse clinical outcomes and a longer DNT.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.