The characteristics of some population groups (patients with comorbidities, women of childbearing age, and the elderly) may limit epilepsy management. Antiepileptic treatment in these patients may require adjustments.

DevelopmentWe searched articles in Pubmed, clinical practice guidelines for epilepsy, and recommendations by the most relevant medical societies regarding epilepsy in special situations (patients with comorbidities, women of childbearing age, and the elderly). Evidence and recommendations are classified according to the prognostic criteria of Oxford Centre of Evidence-Based Medicine (2001) and the European Federation of Neurological Societies (2004) for therapeutic interventions.

ConclusionsEpilepsy treatment in special cases of comorbidities must be selected properly to improve efficacy with the fewest side effects. Adjusting antiepileptic medication and/or hormone therapy is necessary for proper seizure management in catamenial epilepsy. Exposure to antiepileptic drugs (AED) during pregnancy increases the risk of birth defects and may affect fetal growth and/or cognitive development. Postpartum breastfeeding is recommended, with monitoring for adverse effects if sedative AEDs are used. Finally, the elderly are prone to epilepsy, and diagnostic and treatment characteristics in this group differ from those of other age groups. Although therapeutic limitations may be more frequent in older patients due to comorbidities, they usually respond better to lower doses of AEDs than do other age groups.

En el tratamiento de la epilepsia existen una serie de comorbilidades y grupos poblacionales (mujeres en edad fértil y ancianos) para los cuales podemos encontrar limitaciones en el manejo y precisar ajustes del tratamiento.

DesarrolloBúsqueda de artículos en Pubmed y recomendaciones de las Guías de práctica clínica en epilepsia y sociedades científicas más relevantes referentes la epilepsia en situaciones especiales (comorbilidades, mujeres en edad fértil, ancianos). Se clasifican las evidencias y recomendaciones según los criterios pronósticos del Oxford Center of Evidence-Based Medicine (2001) y de la European Federation of Neurological Societies (2004) para las actuaciones terapéuticas.

ConclusionesEn las diversas comorbilidades, es necesaria una adecuada selección del tratamiento para mejorar la eficacia con el menor número de efectos secundarios. En la epilepsia catamenial es necesario un ajuste de la medicación antiepiléptica y/u hormonal, para poder controlar correctamente las crisis. La exposición a fármacos antiepilépticos durante la gestación aumenta el riesgo de malformaciones congénitas (MC) y puede afectar al crecimiento fetal y/o al desarrollo cognitivo. En el puerperio se aconseja la lactancia materna, vigilando los efectos adversos si se usan fármacos sedantes. Finalmente, los ancianos son una población muy susceptible de presentar epilepsia y que tiene unas características diferenciales con respecto a otros grupos de edad para el diagnóstico y el tratamiento. Estos pacientes pueden presentar con mayor frecuencia limitaciones terapéuticas por sus comorbilidades, pero suelen responder mejor al tratamiento y a dosis más bajas que en el resto de grupos de edad.

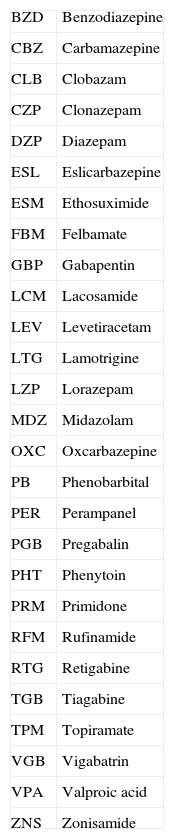

Epidemiological studies identify higher numbers of concomitant diseases among epilepsy patients. The type of associated comorbidity is important in determining the most appropriate treatment for controlling epileptic seizures (ES). Abbreviations of the main antiepileptic drugs (AED) are listed in Table 1.

Abbreviations of antiepileptic drugs.

| BZD | Benzodiazepine |

| CBZ | Carbamazepine |

| CLB | Clobazam |

| CZP | Clonazepam |

| DZP | Diazepam |

| ESL | Eslicarbazepine |

| ESM | Ethosuximide |

| FBM | Felbamate |

| GBP | Gabapentin |

| LCM | Lacosamide |

| LEV | Levetiracetam |

| LTG | Lamotrigine |

| LZP | Lorazepam |

| MDZ | Midazolam |

| OXC | Oxcarbazepine |

| PB | Phenobarbital |

| PER | Perampanel |

| PGB | Pregabalin |

| PHT | Phenytoin |

| PRM | Primidone |

| RFM | Rufinamide |

| RTG | Retigabine |

| TGB | Tiagabine |

| TPM | Topiramate |

| VGB | Vigabatrin |

| VPA | Valproic acid |

| ZNS | Zonisamide |

Selecting ES treatment in patients with comorbidities that lack a causal relationship with epilepsy requires contemplation of the following1,2:

- 1.

Concurrent diseases or drugs can modify seizure frequency.

- 2.

Metabolism of AEDs can be altered by diseases or interactions with other drugs.

- 3.

AEDs can exacerbate medical conditions due to their possible adverse effects.

- 4.

In patients with medical or surgical conditions, treatment options for epilepsy can be limited by the possible routes of administration and the patient's clinical situation.

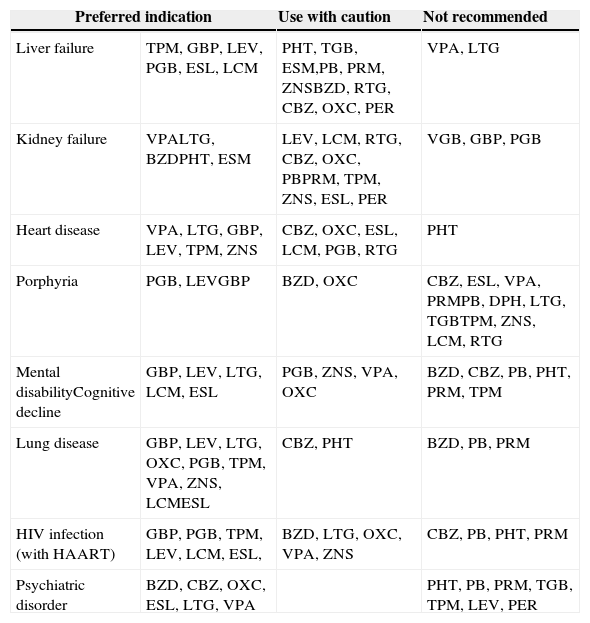

No controlled and randomised clinical trials specifically designed for these clinical situations have been conducted. Most of the available information comes from case series and retrospective analyses, expert opinions, or recommendations from different CPGs1–4 with a level of evidence (LE) of IV, which are listed in Table 2.

Antiepileptic drugs of choice for different diseases. GE-SEN recommendations.

| Preferred indication | Use with caution | Not recommended | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver failure | TPM, GBP, LEV, PGB, ESL, LCM | PHT, TGB, ESM,PB, PRM, ZNSBZD, RTG, CBZ, OXC, PER | VPA, LTG |

| Kidney failure | VPALTG, BZDPHT, ESM | LEV, LCM, RTG, CBZ, OXC, PBPRM, TPM, ZNS, ESL, PER | VGB, GBP, PGB |

| Heart disease | VPA, LTG, GBP, LEV, TPM, ZNS | CBZ, OXC, ESL, LCM, PGB, RTG | PHT |

| Porphyria | PGB, LEVGBP | BZD, OXC | CBZ, ESL, VPA, PRMPB, DPH, LTG, TGBTPM, ZNS, LCM, RTG |

| Mental disabilityCognitive decline | GBP, LEV, LTG, LCM, ESL | PGB, ZNS, VPA, OXC | BZD, CBZ, PB, PHT, PRM, TPM |

| Lung disease | GBP, LEV, LTG, OXC, PGB, TPM, VPA, ZNS, LCMESL | CBZ, PHT | BZD, PB, PRM |

| HIV infection (with HAART) | GBP, PGB, TPM, LEV, LCM, ESL, | BZD, LTG, OXC, VPA, ZNS | CBZ, PB, PHT, PRM |

| Psychiatric disorder | BZD, CBZ, OXC, ESL, LTG, VPA | PHT, PB, PRM, TGB, TPM, LEV, PER | |

HAART: highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Special considerations and specific strategies for treatment of women with epilepsy (WWE) must be contemplated. Doctors should consider not only ES control, but also short- and long-term side effects of AEDs, effects of sex hormones on ES, and the impact of epilepsy and AEDs on patients’ reproductive health and quality of life. These special considerations are the most important for pregnant patients since both ES and treatment with AEDs can have negative effects on the foetus.

Epilepsy, fertility, and sexualityThe main problems that WWE face regarding fertility and sexuality are as follows5–8:

- –

Higher rates of infertility and sexual dysfunction.

- –

A higher prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome, even in women not taking AEDs. This prevalence increases in patients treated with VPA, especially when treatment onset is before the age of 20.

- –

Patients should be asked routinely about their menstrual cycles and any infertility, excessive weight gain, hirsutism, galactorrhoea, or sexual dysfunction.

- –

If anomalies are detected, doctors should consider hormone level measurements, a pelvic ultrasound study, or a pituitary neuroimaging scan.

- –

If the cause of the problem is associated with one AED, an alternative treatment with another AED should be designed.

Epileptic seizure frequency may be higher in any of 3 phases: perimenstrual (the most frequent), periovulatory, and in the second half of the cycle during a defective (anovulatory) luteal phase.5 Approximately one-third of all WWE experience twice as many seizures during these phases of the menstrual cycle as they do on the remaining days. The literature includes treatment plans designed by experts who offer the following recommendations7 (LE IV):

- 1.

Increase the AED dose during perimenstrual and ovulatory phases.

- 2.

Use BZD, especially clobazam dosed at 10-30mg/day of the perimenstrual phase.

- 3.

Use acetazolamide dosed at 250mg/day during the perimenstrual and ovulatory phases.

- 4.

Start hormone contraceptives, and for patients with anovulatory cycles, hormone replacement therapy (progesterone), always with the supervision of a gynaecologist.

The evidence does not point to a higher critical frequency in conjunction with combined hormonal contraceptives (OC).

Pregnancy and deliveryMost WWE experience uneventful pregnancies and normal deliveries of healthy offspring. Frequency of ES usually remains unchanged during pregnancy, childbirth, or puerperium9 (LE II). Plasma levels of AEDs can change during pregnancy. Increased clearance of PHT, CBZ, and LTG with considerable inter-individual variability is observed, so experts recommend monitoring those levels at least quarterly. Controlling plasma levels or adjusting doses of LEV and OXC is also needed when possible.

Most WWE have uneventful pregnancies, although their risk of complications may be higher9 (LE II). Considerations regarding childbirth and puerperium10:

- –

Vaginal delivery is recommended.

- –

Caesarean delivery can be considered in cases of high risk of GTCS (1%-3%), or if prolonged or frequent CPS make it difficult for the woman to labour.

- –

Epidural anaesthesia can be administered.

- –

Using prostaglandins is not contraindicated.

- –

Plasma levels should be checked 2 to 3 weeks after childbirth. If doses were changed during pregnancy, they should be adjusted again, especially if patient is breastfeeding. In cases of treatment with PRM, OXC, and LTC, monitor immediately.

- –

Advice on sleep hygiene.

Exposure to AEDs during pregnancy is associated with increased risk of congenital malformations (CM), and it can have a negative impact on fetal growth and cognitive development.13

Table 3 shows the percentage of malformations caused by AEDs in monotherapy and recorded in the EURAP registry as of 2010.14 If the patient needs to be treated with VPA despite this risk, we should try to use the lowest amount possible (<800mg) divided in several doses. VPA at doses lower than 700mg presents a risk similar to that of CBZ dosed at 400 to 1000mg, PB<150mg, and LTG>300mg11 (LE III).

Number of prospective pregnancies following treatment with AEDs in monotherapy; percentage of malformations detected up to one year after birth. 95% confidence interval (N=4540). EURAP 2010 registry.14

| AED | No. of pregnancies | Malformations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 95% CI | ||

| ZM | 1 | 0 (0.0) | |

| BZ | 1402 | 79 (5.6) | (4.5-7.0) |

| CLB | 9 | 0 (0.0) | |

| CZP | 36 | 0 (0.0) | |

| ESM | 8 | 0 (0.0) | |

| FBM | 3 | 0 (0.0) | |

| GBP | 23 | 0 (0.0) | |

| LTG | 1280 | 37 (2.9) | (2.1-4.0) |

| LEV | 126 | 2 (1.6) | (0.4-5.6) |

| OXC | 184 | 6 (3.3) | (1.5-6.9) |

| PB | 217 | 16 (7.4) | (4.6-11.6) |

| PHT | 103 | 6 (5.8) | (2.7-12.1) |

| PGB | 1 | 0 (0.0) | |

| PRM | 34 | 2 (5.9) | (1.6-19.1) |

| Sulthiame | 1 | 0 (0.0) | |

| TPM | 73 | 5 (6.8) | (3.0-15.1) |

| VPA | 1010 | 98 (9.7) | (8.0-11.7) |

| VGB | 4 | 0 (0.0) | |

| ZNS | 3 | 0 (0.0) | |

| Total | 4540 | 251 (3.3) | (2.2-5.0) |

Treatment with VPA, PB, polytherapy, and a history of 5 or more GTCS during pregnancy is associated with the highest risk of cognitive disorders for children of WWE. Recently published studies show a dose-dependent risk for valproate,11 and treatment with folic acid during pregnancy and breastfeeding has a positive impact on results at 6 years.

Teratogenicity of novel antiepileptic drugsThere is currently no reliable data on the more novel AEDs, although some have been on the market for more than 10 years. Few articles have addressed this subject and the number of patients on monotherapy is also low. A larger number of cases will be needed to examine any differences regarding such specific malformations as cleft palate and ventricular septal defect, and less frequent ones such as anencephaly.

In 2011, the Food and Drug Administration changed TPM from group C to group D since the North American antiepileptic drug pregnancy registry (NAAED) found a 4.2% risk of CMs (15/359 on monotherapy), with a cleft palate prevalence of 1.4%. Data for LEV is available from 4 CM registries: the United Kingdom registry reporting 2 cases/304 patients on monotherapy; EURAP, with a risk of 1.6%11 (2/126 on monotherapy); NAAED, showing a risk of 2.4% (11/450 on monotherapy); and the manufacturer's own registry (UCB) reporting a risk of 7.5% (26/297), although its inclusion criteria and methodology differed from those used in other registries.12 Of 248 published cases treated with OXC, 6 involved CMs (2.4%).15 The number of published cases of patients on GBP, ZNS, PGB, LCM, ESL, RTG, and PER is still very low.

Puerperium and breastfeedingFirst-generation AEDs (PTH, PB, CBZ, and VPA) are not transferred into breast milk in clinically significant amounts, in contrast with GBP, LTG, and TPM16 (LE II-III). Regarding breastfeeding and PB, PRM, and BZD, the newborn may present drowsiness and irritability, and experience difficulty suckling, so close monitoring for adverse effects is needed. Experience with novel AEDs is limited.

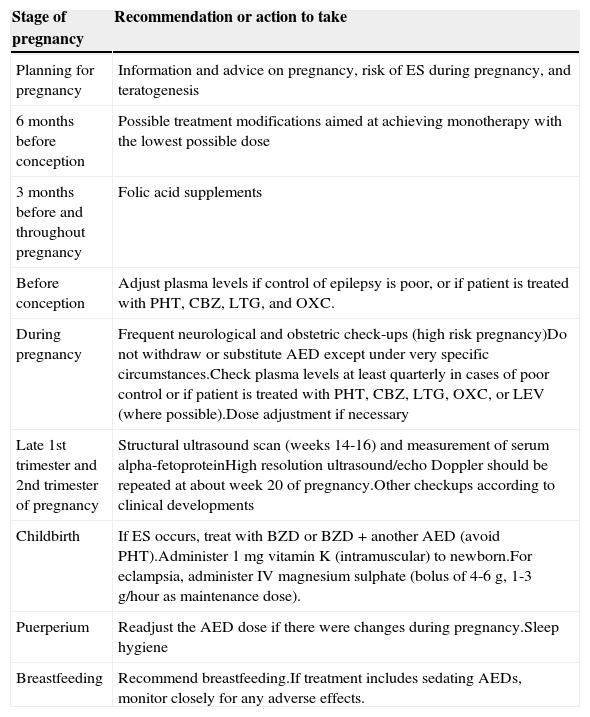

Table 4 includes general information for WWE during preconception, pregnancy, delivery, and puerperium.

Recommendations for WWE during pregnancy, childbirth, and puerperium.

| Stage of pregnancy | Recommendation or action to take |

|---|---|

| Planning for pregnancy | Information and advice on pregnancy, risk of ES during pregnancy, and teratogenesis |

| 6 months before conception | Possible treatment modifications aimed at achieving monotherapy with the lowest possible dose |

| 3 months before and throughout pregnancy | Folic acid supplements |

| Before conception | Adjust plasma levels if control of epilepsy is poor, or if patient is treated with PHT, CBZ, LTG, and OXC. |

| During pregnancy | Frequent neurological and obstetric check-ups (high risk pregnancy)Do not withdraw or substitute AED except under very specific circumstances.Check plasma levels at least quarterly in cases of poor control or if patient is treated with PHT, CBZ, LTG, OXC, or LEV (where possible).Dose adjustment if necessary |

| Late 1st trimester and 2nd trimester of pregnancy | Structural ultrasound scan (weeks 14-16) and measurement of serum alpha-fetoproteinHigh resolution ultrasound/echo Doppler should be repeated at about week 20 of pregnancy.Other checkups according to clinical developments |

| Childbirth | If ES occurs, treat with BZD or BZD+another AED (avoid PHT).Administer 1mg vitamin K (intramuscular) to newborn.For eclampsia, administer IV magnesium sulphate (bolus of 4-6g, 1-3g/hour as maintenance dose). |

| Puerperium | Readjust the AED dose if there were changes during pregnancy.Sleep hygiene |

| Breastfeeding | Recommend breastfeeding.If treatment includes sedating AEDs, monitor closely for any adverse effects. |

Epilepsy and ES in the elderly differ from those in other age groups in their form of presentation, diagnosis, and outcome as described below:

- 1.

Aetiology. Acute and remote symptomatic ES are the most frequent types, accompanied by cerebrovascular disease (40%-50%), followed by degenerative brain disease, primary tumours and metastasis, head trauma, and infections of the central nervous system.

- 2.

Type of ES. Partial seizures predominate, especially CPS (38%). The epileptic focus is most frequently located in the frontal lobes, also the predominant location of strokes. The main signs of ES differ in the following points:

- –

Auras and automatisms are rare and tend to be non-specific if they occur.

- –

There is a higher incidence of motor and sensory symptoms than of psychic symptoms. Epileptic seizures sometimes manifest as prolonged confusional episodes, mental slowness, memory lapses, strange behaviour, recurring periods of hypo-responsiveness, and other unclear symptoms which may be the only manifestations in the critical period.

- –

Symptoms sometimes include syncopal features.

- –

Secondarily generalised tonic clonic seizures are less frequent in the elderly than in younger adults, but can cause major trauma.

- –

The duration of post-ictal phase can be very long. Prolonged Todd paralysis has a high prevalence in cases of ES of vascular origin.

- –

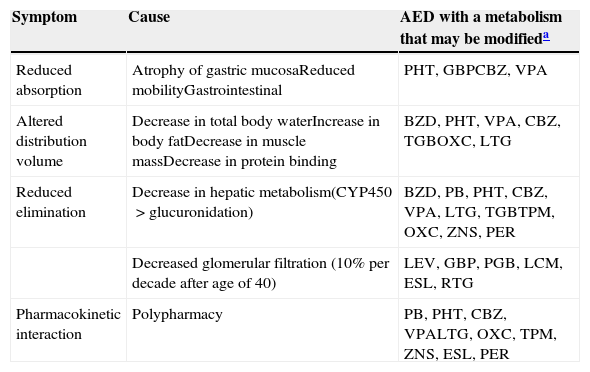

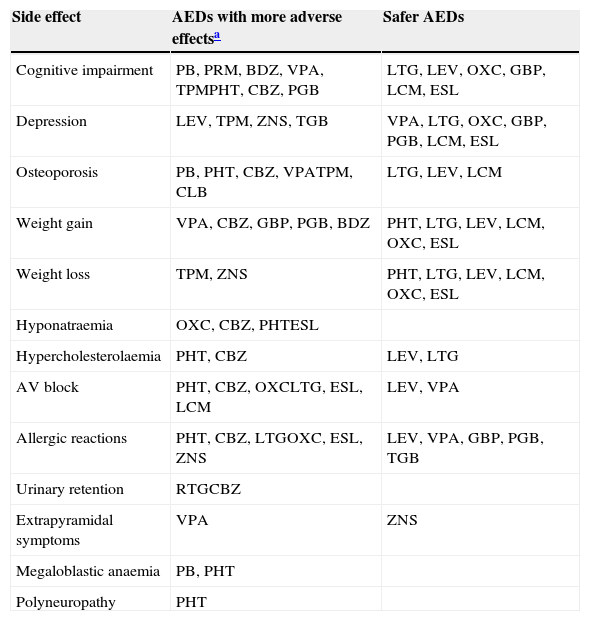

Table 5 displays the main metabolic changes and the AEDs responsible for them. Table 6 includes the adverse effects we consider to be particularly relevant given the characteristics of elderly patients, and the AEDs that are involved to a greater or lesser extent.

- –

Selecting AEDs. Studies of AEDs in populations older than 65 years, and with high levels of evidence, are quite scarce. Case series, opinions, and expert consensus documents on epilepsy have been published21–26 (LE IV). The AEDs most frequently recommended for elderly patients are LEV, which is not hepatically metabolised and has no known interactions; and LTG, whose hepatic metabolism and protein binding are associated with a slightly increased risk of drug interactions and severe allergic reactions. These effects can be avoided with slow titration.27 ZNS, shown to be non-inferior to CBS as treatment for partial seizures in a large population including subjects older than 75 years28 (LE I), is now indicated for use as epilepsy monotherapy.

Pharmacodynamic modifications in the elderly.

| Symptom | Cause | AED with a metabolism that may be modifieda |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced absorption | Atrophy of gastric mucosaReduced mobilityGastrointestinal | PHT, GBPCBZ, VPA |

| Altered distribution volume | Decrease in total body waterIncrease in body fatDecrease in muscle massDecrease in protein binding | BZD, PHT, VPA, CBZ, TGBOXC, LTG |

| Reduced elimination | Decrease in hepatic metabolism(CYP450>glucuronidation) | BZD, PB, PHT, CBZ, VPA, LTG, TGBTPM, OXC, ZNS, PER |

| Decreased glomerular filtration (10% per decade after age of 40) | LEV, GBP, PGB, LCM, ESL, RTG | |

| Pharmacokinetic interaction | Polypharmacy | PB, PHT, CBZ, VPALTG, OXC, TPM, ZNS, ESL, PER |

Adverse effects of special relevance for the elderly.

| Side effect | AEDs with more adverse effectsa | Safer AEDs |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive impairment | PB, PRM, BDZ, VPA, TPMPHT, CBZ, PGB | LTG, LEV, OXC, GBP, LCM, ESL |

| Depression | LEV, TPM, ZNS, TGB | VPA, LTG, OXC, GBP, PGB, LCM, ESL |

| Osteoporosis | PB, PHT, CBZ, VPATPM, CLB | LTG, LEV, LCM |

| Weight gain | VPA, CBZ, GBP, PGB, BDZ | PHT, LTG, LEV, LCM, OXC, ESL |

| Weight loss | TPM, ZNS | PHT, LTG, LEV, LCM, OXC, ESL |

| Hyponatraemia | OXC, CBZ, PHTESL | |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | PHT, CBZ | LEV, LTG |

| AV block | PHT, CBZ, OXCLTG, ESL, LCM | LEV, VPA |

| Allergic reactions | PHT, CBZ, LTGOXC, ESL, ZNS | LEV, VPA, GBP, PGB, TGB |

| Urinary retention | RTGCBZ | |

| Extrapyramidal symptoms | VPA | ZNS |

| Megaloblastic anaemia | PB, PHT | |

| Polyneuropathy | PHT |

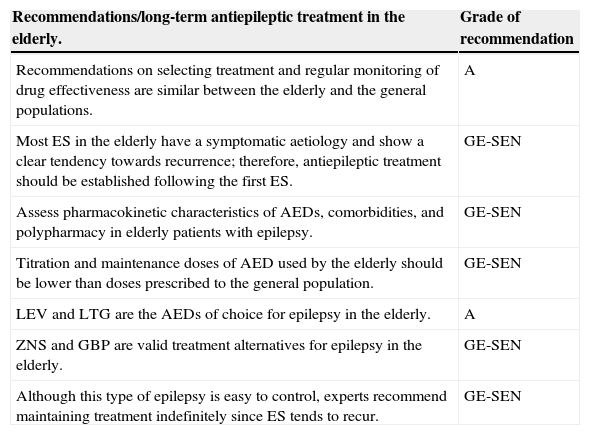

Assessing associated comorbidities when selecting treatment is very important, especially for elderly patients. Comorbidities can guide us in choosing a specific antiepileptic drug (see the grades of recommendation below).

| Recommendations/long-term antiepileptic treatment in the elderly. | Grade of recommendation |

|---|---|

| Recommendations on selecting treatment and regular monitoring of drug effectiveness are similar between the elderly and the general populations. | A |

| Most ES in the elderly have a symptomatic aetiology and show a clear tendency towards recurrence; therefore, antiepileptic treatment should be established following the first ES. | GE-SEN |

| Assess pharmacokinetic characteristics of AEDs, comorbidities, and polypharmacy in elderly patients with epilepsy. | GE-SEN |

| Titration and maintenance doses of AED used by the elderly should be lower than doses prescribed to the general population. | GE-SEN |

| LEV and LTG are the AEDs of choice for epilepsy in the elderly. | A |

| ZNS and GBP are valid treatment alternatives for epilepsy in the elderly. | GE-SEN |

| Although this type of epilepsy is easy to control, experts recommend maintaining treatment indefinitely since ES tends to recur. | GE-SEN |

| Recommendations/epilepsy treatment in elderly patients with other comorbidities. | Grade of recommendation |

|---|---|

| Parenteral AEDs of choice in patients with cardiac arrhythmias: BZD, VPA, and LEV; PHT and LCM should be avoided. | GE-SEN |

| AEDs indicated for patients with heart disease: GBP, LEV, LTG, TPM, VPA, and ZNS | GE-SEN |

| In patients with respiratory failure, avoid parenteral administration of AEDs that cause respiratory depression (barbiturates and BZD). Their alternative options are LEV, VPA, and LCM. | GE-SEN |

| In patients with osteopoenia, hypercholesterolaemia, and hypothyroidism, avoid AEDs that are enzymatic inductors. | GE-SEN |

| The most appropriate AEDs for long-term treatment of patients with liver failure are TPM, GBP, LEV, PGB, and LCM. Use of LTG, CBZ, VPA, and PB is not recommended. | GE-SEN |

| The most recommendable AEDs in cases of kidney failure treated with haemodialysis are BZD, CBZ, PHT, VPA, and LTG. Use of VGB, GBP, and PGB is not recommended. | GE-SEN |

| AEDs of choice for patients with mental disabilities and cognitive impairment: LTG, GBP, LEV, OXC, ESL, and LCM | GE-SEN |

| AEDs recommended in cases of psychiatric disorder: BZD, CBZ, OXC, ESL, LCM, LTG, and VPA | GE-SEN |

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to thank all who contributed to drafting these guidelines issued by the SEN's Epilepsy Study Group: Maria Jose Aguilar-Amat Prior, Juan Alvarez-Linera Prado, Nuria Bargalló Alabart, Juan Luis Becerra Cuñat, Trinidad Blanco Hernández, Dulce Campos Blanco, Francisco Cañadillas Hidalgo, Mar Carreño Martínez, Carlos Casas Fernández, Antonio Donaire Pedraza, Irene Escudero Martínez, Merce Falip Centellas, Maria Isabel Forcadas Berdusan, Alberto Garcia Martínez, Irene Garcia Morales, Antonio Gil-Nagel Rein, José Luis Herranz Fernández, Vicente Ibañez Mora, Francisco Javier López González, Javier López-Trigo Pichó, Mercedes Martin Moro, Albert Molins Albanell, Maria Dolores Morales Martínez, Jaime Parra Gómez, Rodrigo Rocamora Zuñiga, Xiana Rodriguez Osorio, Juan Jesus Rodriguez Uranga, Miguel Rufo Campos, Rosa Ana Saiz Diaz, Xavier Salas-Puig, Juan Carlos Sánchez Alvarez, Jerónimo Sancho Rieger, Pedro Jesús Serrano Castro, Jose Serratosa Fernandez, Xabier Setoain Perego, Carlos Tejero Juste, Rafael Toledano Delgado, Manuel Toledo Argany, Francisco Villalobos Chaves, Vicente Villanueva Haba, and César Viteri Torres.

Please cite this article as: Mauri Llerda JA, Suller Marti A, de la Peña Mayor P, Martínez Ferri M, Poza Aldea JJ, Gomez Alonso J, et al. Guía oficial de la Sociedad Española de Neurología de práctica clínica en epilepsia. Epilepsia en situaciones especiales: comorbilidades, mujer y anciano. Neurología. 2015;30:510–517.