Transient cerebral alterations in epilepsy patients were first highlighted in 1980 by Rumack et al.1 Most of those described in the literature refer to patients with partial or generalized status epilepticus, with scant reports in patients with isolated epileptic seizures.2

In both computed tomography and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, these lesions may imitate other pathological entities; therefore, it is important to recognize them in order to avoid unnecessary diagnostic procedures such as cerebral biopsy or invasive vascular studies.3

We describe the case of a female patient presenting a transient cerebral lesion on MR imaging after suffering a partial complex seizure.

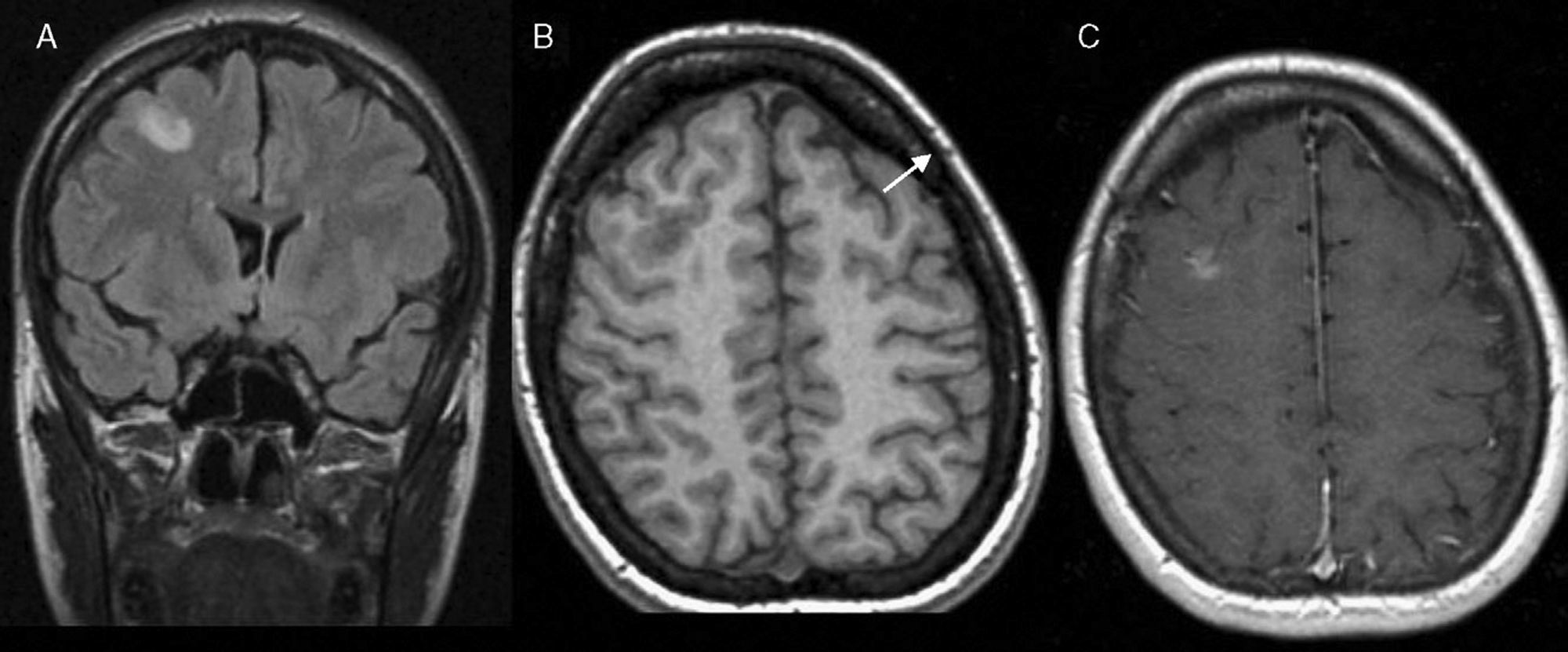

A female, aged 29, was diagnosed three years previously as having secondarily generalized focal epilepsy. The seizures consisted in bouts of forced leftward oculocephalic version, lasting for 1–2min. The patient had previously remained asymptomatic with pharmacological treatment (valproate 500mg/12h per os). She returned to the emergency department after presenting several focal crises with characteristics similar to those at the time of diagnosis. The general and neurological examinations were normal. Her general work-up, electrocardiogram and chest X-ray showed no pathological findings. Three days after admission, an MRI scan was performed and it revealed the existence of a cortical–subcortical lesion in the right middle frontal gyrus, with poor definition, hyperintense in T2, DP and FLAIR sequences, diffusely enhanced after administration of intravenous (IV) contrast (Fig. 1). The electroencephalogram showed normal baseline cerebral activity, with slow-irritative focality in the frontal region of the right cerebral hemisphere. In view of these results, treatment was begun with oral valproate and IV levetiracetam, with an immediate improvement being observed with remission of the seizures.

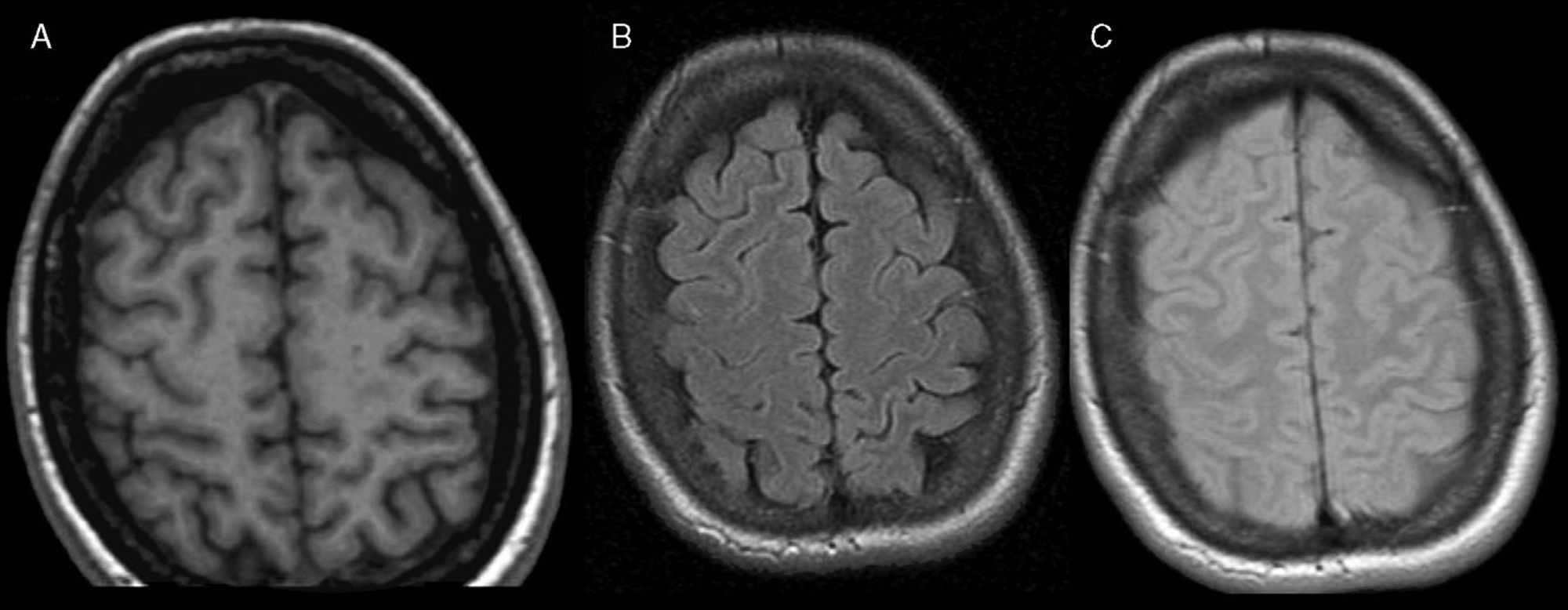

The patient was re-assessed three months later and remained asymptomatic, presenting normal general and neurological examinations. The follow-up MRI did not show any of the parenchymatous lesions reported earlier (Fig. 2).

Recent advances in MRI provide new opportunities for the early identification of neuronal damage and the areas affected in an epileptic seizure.4 Generally speaking, the radiological changes reflected in MRI are related to metabolic response, increased neuronal activity and greater vascular provision during the seizure.5

Vasogenic oedema may occur due to the bursting of the blood–brain barrier and increased vascular flow at the focus of the epileptogenous activity, manifested through MRI by hyperintensity in T2 and FLAIR, areas of cerebral hypervascularization in the angio-MRI perfusion study and leptomeningeal or gyriform enhancement with the administration of IV contrast.6 There is also cytotoxic oedema, revealing restriction of diffusion in DWI images,4 thus supporting the idea that there is cell damage, reversible in these cases.5

Both types of oedema and especially cytotoxic oedema correlate with the frequency and duration of the crises. This justifies their more frequent description after status epilepticus and the fact that certain tests, such as cerebral angio-MRI and MRI with diffusion sequences, are normal in cases of isolated crises and even in short-lasting status epilepticus.6

Furthermore, increased energy demand during the seizure leads to an increase in the concentration of lactate in spectroscopic images. More controversial is the increase in N-acetylaspartate, which diminishes immediately after the convulsions.7

These lesions do not present any mass effect; on occasions, they may not take up any contrast and may affect different parts of the brain (with the temporal lobe most frequently involved). They may be unilateral or bilateral and their main characteristic is their transient nature, with an extremely variable interval until their resolution, ranging between 1 and 12 months.6

In view of these radiological findings, differential diagnosis must fundamentally rule out transient ischaemic infarction, tumours such as astrocytoma, complicated migraine and infectious processes such as cerebritis.

Therefore, recognizing this kind of lesion in patients who have presented a convulsive seizure may avoid the need for invasive procedures such as cerebral biopsy. After several months have elapsed following the bout, we must conduct a further check-up with MRI, in order to ensure the transient and benign nature of the lesions.

Please cite this article as: Gallardo Muñoz I, et al. Alteraciones cerebrales transitorias en resonancia magnética tras crisis epilépticas aisladas. Neurología 2011;26:434–6.