Spastic paraplegia type 7 (SPG7; OMIM #607259) is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the SPG7 gene, which encodes the mitochondrial metalloprotease paraplegin.1 It accounts for approximately 5%-12% of all autosomal recessive forms and up to 7% of sporadic cases in adults. It has also been associated with symptoms of cerebellar ataxia,2 which may constitute the most relevant clinical manifestation. However, phenotypic variations are more complex; the literature includes cases of chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia,3 primary lateral sclerosis,4 and parkinsonism.5

Over 131 pathogenic variants have been described (Human Gene Mutation Database, accessed 14 July 2019). We report the cases of 3 sisters from a Spanish family, who presented ataxia and spasticity and were carriers of 2 single nucleotide variants of uncertain significance in the SPG7 gene.

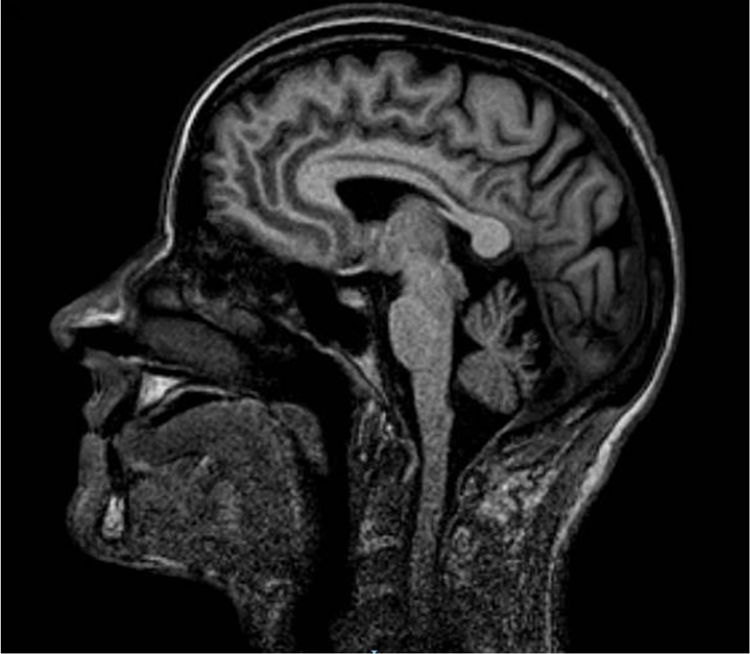

We studied a family of 7 siblings born to non-consanguineous parents and with no family history of neurological disease. Three of them (3 women) reported progressive difficulty walking, with instability and dysarthria appearing in the third decade of life. A clinical examination performed after 20 years of disease progression revealed multidirectional nystagmus, dysarthria, global hyperreflexia with bilateral extensor plantar reflex, and marked spasticity of the lower limbs, with the patients requiring bilateral support to walk. The eldest of the 3 sisters also presented cognitive impairment, ophthalmoparesis, upper limb dysmetria, and wide-based gait. All 3 showed cerebellar atrophy on MR images (Fig. 1). The remaining siblings were not affected (Fig. 2A).

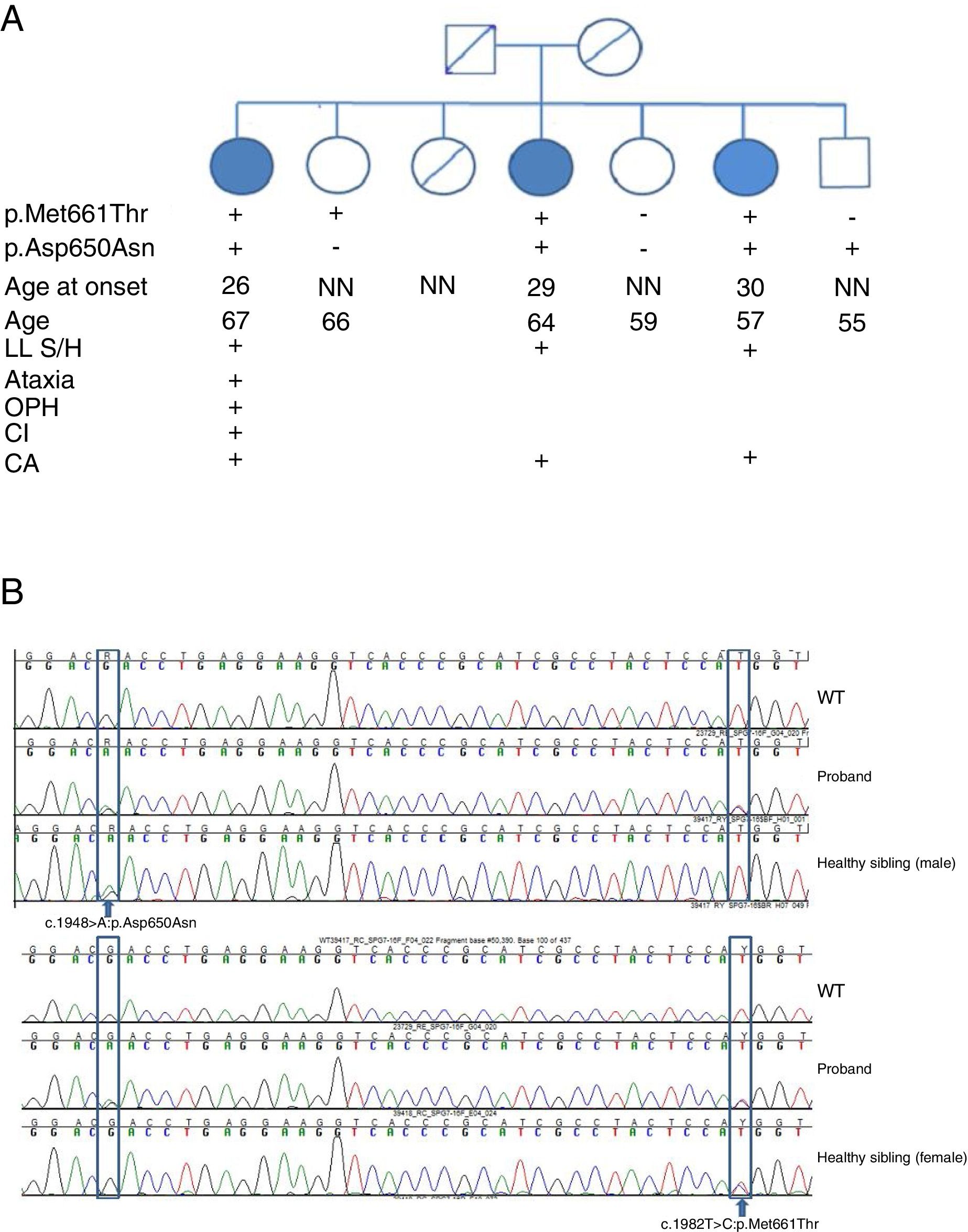

SPG7 mutations and clinical correlations. (A) Pedigree chart of the family. CA: cerebellar atrophy; CI: cognitive impairment; LL S/H: lower limb spasticity/hyperreflexia; NN: neurologically normal; OPH: ophthalmoparesis; +: present; –: absent. (B) Sanger sequencing of the SPG7 gene. Heterozygous mutations are indicated with arrows.

After ruling out secondary causes and the mutations most frequently associated with ataxia and spastic paraparesis in the proband, we conducted a genetic study of the SPG7 gene. We detected 2 missense mutations, and decided to perform the genetic study in the remaining siblings.

Peripheral blood samples were collected and we performed DNA amplification by PCR and traditional DNA sequencing with the ABI 3730® analyser (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, CA, USA). We studied all coding exons and exon-intron boundaries. We also analysed small deletions/insertions and point mutations in the coding regions and splice sites of SPG7.

We detected 2 compound missense mutations (NM_003119.3:c.1982T>C:p.Met661Thr and NM_003119.3:c.1948G>A:p.Asp650Asn) in heterozygosis in the 3 siblings affected. Two unaffected siblings carried one of the mutations each, and another carried neither (Fig. 2B).

The clinical and genetic significance of the variants was established by studying population frequencies, conservation scores (GERP, Phylophen, SiPhy), and prediction scores (SIFT, Polyphen, Mutation Taster, Mutation Assessor, LRT, CADD, DANN) for each variant. We reviewed the available information on SPG7 variants previously associated with the disease (published articles, OMIM®, GeneReviews®, ClinVar, Human Gene Mutation Database). We also studied family segregation, although no samples were available from either of the parents.

In silico predictions and the clinical and genetic criteria studied support the pathogenic potential of both variants. Variant p.Met661Thr is not included in population frequency databases, and was found in compound heterozygosity in a patient with suspected pure spastic paraparesis.6 Variant p.Asp650Asn, in turn, presents a population frequency of 0.001% and had previously been detected in a sporadic case in a patient with ataxia as the main symptom and who also presented symptoms of upper motor neuron involvement.7 In both cases, all conservation and prediction algorithms signalled a functional impact on the protein.

The patients presented here show the characteristic clinical features, with some exceptions. The patient with the longest disease progression time presented more severe ataxia and less common symptoms, including ophthalmoparesis and cognitive impairment.

These phenotypic differences may be explained by the accumulation of symptoms over the period of disease progression; however, we lack prospective follow-up data.

Both mutations have been classified as variants of uncertain significance, and have previously been described in only 2 cases. The clinical and genetic data presented here support the pathogenic role of these mutations. However, further research is necessary to evaluate their pathogenicity.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report the occurrence of both variants in a single family with spastic ataxia. Although no samples were available from the parents, the segregation of both variants in different affected and non-affected siblings suggests that each variant comes from one parent.

Please cite this article as: Fernández-Moreno MC, Castro-Fernández C, Viloria-Peñas MM, Castilla-Guerra L. Familia española portadora de una mutación en heterocigosis compuesta en el gen SPG7: de la incertidumbre a la realidad clínica. Neurología. 2020;35:694–696.