SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes the disease COVID-19, was first described in Wuhan in December 2019. The typical symptoms of COVID-19 are fever, dry cough, dyspnoea, and general discomfort.1–9 The most severe cases involve massive release of proinflammatory cytokines that cause alveolar damage associated with respiratory insufficiency and multi-organ failure, leading to the death of the patient.2 Neurological manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection include headache, dizziness, impaired level of consciousness, and anosmia.3 We present the case of a patient with acute transverse myelitis associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The patient is a 53-year-old man with no relevant medical history who was diagnosed 2 days earlier with SARS-CoV-2 infection; he consulted due to dysaesthesia in the lower limbs and inability to walk independently. He presented no respiratory symptoms or lung involvement at any time.

Neurological examination revealed preserved motor strength, vibratory and tacto-algesic hypoaesthesia at the T9-T10 sensory level, exaggerated deep tendon reflexes in the lower limbs, bilateral Babinski sign, ataxic gait, and urinary retention.

Head and lumbar spine CT studies revealed no abnormal findings. A blood analysis detected mildly elevated levels of acute-phase reactants. Autoimmune test results were normal. Suspecting acute transverse myelitis, we performed a CSF analysis, which revealed pleocytosis with mononuclear cells and high protein levels, with no glucose uptake. A microbiological study of the CSF sample yielded negative results.

The neurological symptoms significantly worsened during hospitalisation, with progression to severe paraparesis, and a urinary catheter had to be placed.

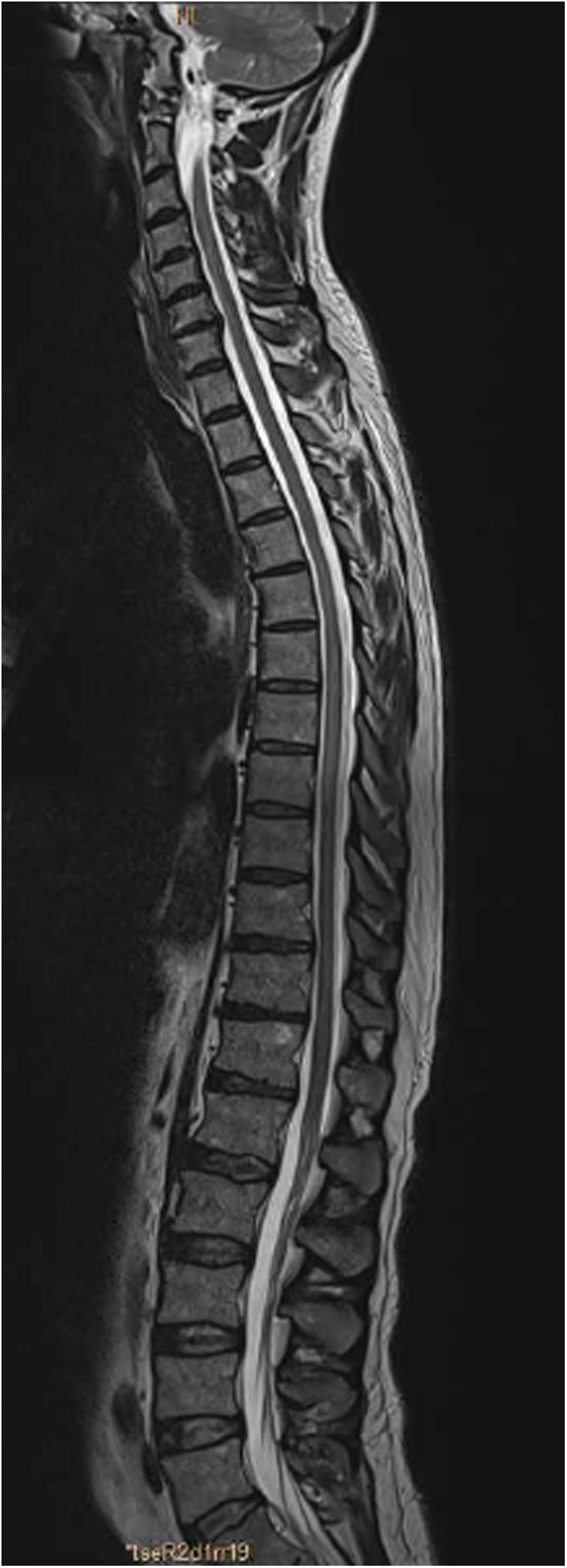

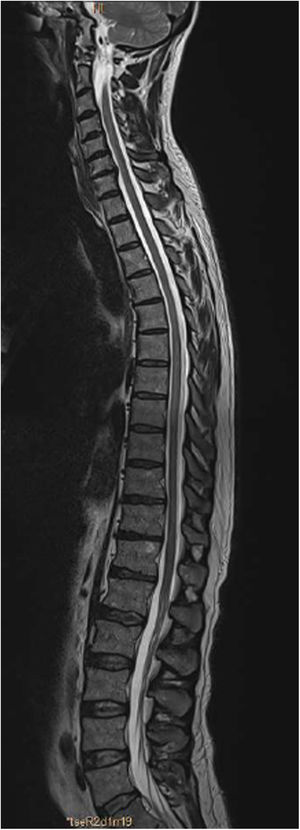

An MRI study (Figs. 1 and 2) revealed a slight signal alteration in the T6-T11 segments, with hyperintensity on T2-weighted sequences; the lesion did not present gadolinium uptake or mass effect. These findings are compatible with longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis of the thoracic spinal cord.

We administered a 5-day cycle of methylprednisolone dosed at 1000 mg per day, observing no improvement. Due to the ineffectiveness of the treatment, we administered intravenous immunoglobulins dosed at 0.4 g/kg/day for 5 days. Progression was satisfactory, and the patient was able to walk independently at discharge, although impaired proprioception persisted.

The neurological manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection described to date are diverse, and present in up to one-third of patients.4 The most frequent symptoms are headache, dizziness, altered level of consciousness, and anosmia. Isolated cases have been reported of seizures, acute encephalitis, stroke, Guillain-Barré syndrome, and transverse myelitis.3,4

The diagnostic criteria for transverse myelitis include the presence of bilateral sensory, motor, and autonomic dysfunction at a defined sensory level, progression to the maximal level of disability between 4 hours and 21 days, evidence of spinal cord inflammation due to pleocytosis, elevated CSF IgG levels, and gadolinium uptake on MRI, with compressive, neoplastic, vascular, and post-radiation causes having been ruled out.5,6 SARS-CoV-2 infection is diagnosed with PCR testing of a nasopharyngeal swab, given the low sensitivity of PCR testing of CSF.7 The treatment of choice for transverse myelitis is high-dose methylprednisolone; if this is ineffective, intravenous immunoglobulins should be considered.8,9

SARS-CoV-2 can affect the nervous system by direct invasion or through an exaggerated systemic inflammatory response to the virus. The latter mechanism causes increased permeability of the blood-brain barrier and massive release of proinflammatory cytokines, which in turn cause oedema and immune-mediated damage to the spinal cord.3 SARS-CoV-2 has been shown to invade human cells by binding to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor.8,10 Microarray studies have demonstrated ACE2 expression in the cerebral cortex, basal ganglia, hypothalamus, brainstem, and brain capillary endothelium.10 This marked ACE2 receptor expression in the human brain may explain the neuroinvasive capacity of the virus.11,12 The virus may also spread through the central nervous system via the olfactory bulb; studies of intranasal inoculation with SARS-CoV-2 in mice have shown that the virus is able to penetrate the brain, brainstem, and spinal cord.13

Currently, the mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 virulence and the pathophysiology of COVID-19 are not fully understood. Despite this, it seems plausible that the abundant expression of ACE2 receptors in the brain parenchyma favours interaction with the virus, increasing the risk of neurological complications.

FundingThis study received no funding of any kind.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Jauregui-Larrañaga C, Ostolaza-Ibáñez A, Martín-Bujanda M. Mielitis transversa aguda asociada a infección por SARS-CoV-2. Neurología. 2021;36:572–574.