Impulse control disorders (ICD) constitute a complication that may arise during the course of Parkinson's disease (PD). Several factors have been linked to the development of these disorders, and their associated severe functional impairment requires specific and multidisciplinary management. The objective of this study was to evaluate the frequency of ICDs and the clinical and psychopathological factors associated with the appearance of these disorders.

MethodsCross-sectional, descriptive, and analytical study of a sample of 115 PD patients evaluated to determine the presence of an ICD. Clinical scales were administered to assess disease severity, personality traits, and presence of psychiatric symptoms at the time of evaluation.

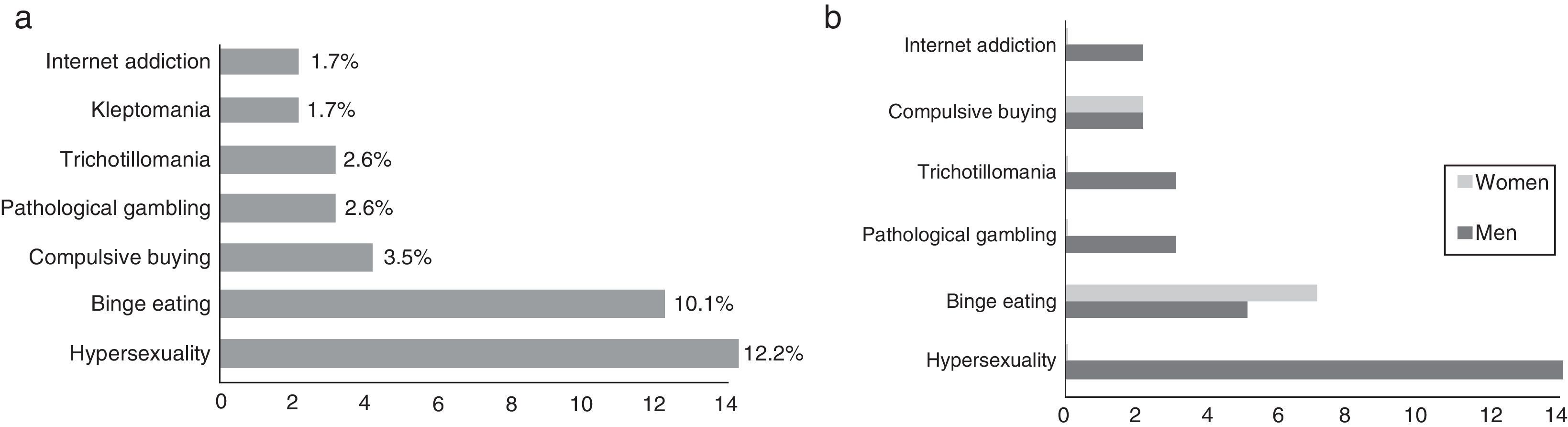

ResultsOf the 115 patients with PD, 27 (23.48%) displayed some form of ICD; hypersexuality, exhibited by 14 (12.2%), and binge eating, present in 12 (10.1%), were the most common types. Clinical factors associated with ICD were treatment with dopamine agonists (OR: 13.39), earlier age at disease onset (OR: 0.92), and higher score on the UPDRS-I subscale; psychopathological factors with a significant association were trait anxiety (OR: 1.05) and impulsivity (OR: 1.13).

ConclusionsICDs are frequent in PD, and treatment with dopamine agonists is the most important risk factor for these disorders. High impulsivity and anxiety levels at time of evaluation, and younger age at disease onset, were also linked to increased risk. However, presence of these personality traits prior to evaluation did not increase risk of ICD.

Los trastornos del control de los impulsos (TCI) son una complicación que puede aparecer en los pacientes con enfermedad de Parkinson (EP). Su presencia se ha relacionado con diversos factores y confiere tal gravedad clínica que obliga a realizar un abordaje específico y multidisciplinar. El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar la frecuencia y los factores tanto clínicos como psicopatológicos asociados a su aparición.

MétodosEstudio transversal, descriptivo y analítico con una muestra de pacientes con EP a quienes se evaluó la presencia de algún TCI. Se administraron escalas clínicas para valorar la gravedad de la enfermedad, los rasgos de personalidad y diferentes síntomas psicopatológicos presentes en el momento de la valoración.

ResultadosLa muestra fue de 115 pacientes, de los cuales un 23,48% (n=27) presentaba algún TCI, siendo los más frecuentes la hipersexualidad en el 12,2% (n=14) y la ingesta compulsiva en el 10,1% (n=12). De los diferentes factores clínicos y psicopatológicos analizados, se asociaron con la presencia de TCI el tratamiento con agonistas dopaminérgicos (OR: 13,39), la edad de inicio más precoz de la enfermedad (OR: 0,92), una puntuación mayor en la escala UPDRS-I (OR: 1,93), la ansiedad como rasgo (OR: 1,05) y la impulsividad no planificada (OR: 1,13).

ConclusionesLos TCI son frecuentes en la EP. El tratamiento con agonistas dopaminérgicos es el factor de riesgo más importante. Niveles elevados de impulsividad y ansiedad en el momento de la valoración, así como una edad de inicio precoz, incrementan el riesgo. Sin embargo, los rasgos de personalidad previos no confieren un mayor riesgo.

Parkinson's disease (PD), the second most common neurodegenerative disease, has traditionally been considered a motor disorder resulting from progressive degeneration of the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system. Based on this hypothesis, therapeutic strategies have concentrated on increasing dopamine levels.

Over time, however, several adverse effects of dopamine replacement therapy (DRT) have been described. These include such motor symptoms as dyskinesia and motor fluctuations, as well as non-motor symptoms: psychotic disorders, compulsive behaviour (punding, walkabout, hobbyism), dopamine dysregulation syndrome (addiction to DRT), and impulse control disorders (ICDs).1

Impulsivity, the core feature of ICD, is characterised by quick, unplanned responses to internal or external stimuli. Impulsive people rarely take time to assess the negative impact their actions may have on themselves or other people.2 In ICD, impulsivity can manifest as a wide range of behaviours. Some ICDs described in the general population include pathological gambling, binge eating, compulsive buying, hypersexuality, pyromania, kleptomania, and intermittent explosive disorder.3 Other disorders, such as trichotillomania, fall between impulsive and compulsive disorders. Although obsessive–compulsive disorders have traditionally been classified as ICD, the latest edition of the DSM (DSM-5) places them in the category of obsessive–compulsive and related disorders.4

Prevalence of ICD is higher in patients with PD than in the general population, ranging from 8% to 28%, depending on the sample, methodology, and diagnostic criteria for ICD.5–8 A number of susceptibility factors appear to contribute to ICD. Some of these risk factors are each person's biological vulnerability, a personal and family history of psychiatric disorders associated with impulsivity, male sex, early-onset PD, and longer duration of PD.9–11 Recent studies investigating the potential influence of DRT on these disorders suggest an association between this type of treatment (levodopa and dopamine agonists) and some ICDs.12,13 Although a history of psychiatric disorders associated with impulsivity has been described as a risk factor for developing ICD, few studies have analysed the influence of personality traits on these disorders.14

The present study aims to: (1) analyse the frequency of the different ICDs in a sample of patients with PD who underwent specific tests for detecting ICD, and (2) study the connection between these disorders and several clinical and psychopathological factors.

Subjects and methodsWe conducted a cross-sectional, descriptive, and analytic study of a sample of patients diagnosed with idiopathic PD who were consecutively recruited from the outpatient clinic of the movement disorders unit at Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron from October 2009 to May 2013. The inclusion criteria were: a diagnosis of idiopathic PD according to the diagnostic criteria of the United Kingdom Parkinson's Disease Society Brain Bank,15 absence of dementia (MMSE score>26), receiving stable doses of antiparkinsonian or psychoactive drugs in the past 3 months, and signing an informed consent form. The exclusion criteria were: being unable to sign the informed consent form for any reason, and not completing the study protocol.

All patients underwent a neurological examination, which was conducted by a neurologist specialising in movement disorders. During this examination, the patients were screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria and clinical characteristics were obtained. Disease severity was determined using the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) and the Hoehn and Yahr (HY) scale.16 Likewise, we gathered data on the type of DRT (dopamine agonists [DA], levodopa [LD]) and treatment with other drugs (MAO-B inhibitors, amantadine, antidepressants). We calculated the levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD) and the dopamine agonist equivalent daily dose (DAEDD) following the methodology described in the literature.17

Patients also underwent psychiatric assessment within a month of the neurological examination. Sociodemographic and psychopathological data were gathered. The patients’ psychiatric histories were analysed using a semi-structured clinical interview to screen for Axis I (SCID-I) and Axis II (SCID-II) disorders, according to the DSM-IV-TR.18,19 We also evaluated each ICD separately using the Minnesota Impulsive Disorders Interview.20 This tool screens for pathological gambling, trichotillomania, kleptomania, pyromania, intermittent explosive disorder, compulsive buying, and compulsive sexual behaviour. It consists of an initial screening question which, if answered affirmatively, results in the interviewer asking further questions based on DSM-5 criteria. Following the Minnesota interview, a psychiatrist examined the patients to confirm they met the diagnostic criteria for each ICD. Patients were only diagnosed with an ICD if they also met the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for pathological gambling, binge eating, pyromania, intermittent explosive disorder, trichotillomania, and kleptomania; the Voon's et al.23 criteria for hypersexuality; McElroy's et al.21 criteria for compulsive buying; and the criteria proposed by Young23 for internet addiction.21–23

Personality was evaluated using the Zuckerman–Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire (ZKPQ), which assesses the dimensions integrating the alternative 5-factor model.24 The ZKPQ comprises 5 scales plus the infrequency scale. These scales measure 5 basic personality dimensions based on a psychobiological perspective on personality. These dimensions are: neuroticism-anxiety, activity, sociability, impulsivity-sensation seeking, and aggression-hostility. The ZKPQ also includes the ‘infrequency’ scale, which should only be used to detect inattention to the task or assess response validity.

The psychopathological symptoms present at the time of assessment were analysed using specific scales recommended for PD. More specifically, symptoms of depression were evaluated with the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D),25 whereas severity of anxiety symptoms was evaluated using Spielberger's State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI).26 Impulsivity was assessed with the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11).27 This scale assesses total impulsivity and 3 of its factors (cognitive, motor, and non-planning). Finally, compulsiveness was evaluated with the Maudsley Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory.28

Data analysisStatistical analyses were carried out using PASW Statistics version 17 for Windows (IBM Corp, New York, USA). Quantitative variables were expressed as either means±SD or medians (interquartile range), whereas categorical variables were expressed in percentages (n).

To analyse differences between patients with and without ICD we conducted a univariate analysis using the t test for quantitative variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. The Fisher exact test was applied as necessary. To reduce type I and type II errors, multiple comparisons were corrected using the Benjamini–Hochberg method [pm=p (m+1)/2m].29

The variables found to be statistically significant in the univariate analysis were included in the logistic regression model with backward elimination to analyse which clinical variables, on the one hand, and which psychopathological variables, on the other, were correlated with the presence of an ICD.

The study was approved by the ethics committee at our hospital and complies with the standards of the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki for human research.

ResultsThe sample included 115 patients with a mean age of 63.16±9.06 years; 63.5% (n=73) were men. Median disease duration was 37.1 months (range, 18.1-78.2). The median score on UPDRS Part III was 19 (range, 15.0-23.0).

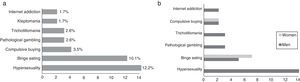

The prevalence of ICD in our sample was 23.48% (n=27); 74.07% (n=20) of these were men. Of the total number of patients with ICD, 63.0% (n=17) had only one type of ICD, 22.2% (n=6) had 2, and 14.8% (n=4) had 3 or more. In our sample, the 2 most frequent types of ICD were hypersexuality (12.2%, n=14) and binge eating (10.1%, n=12) (Fig. 1a). We found marked differences in sex distribution of ICD types: hypersexuality and pathological gambling were clearly more prevalent in men, while binge eating and compulsive buying were only slightly more common among women (Fig. 1b).

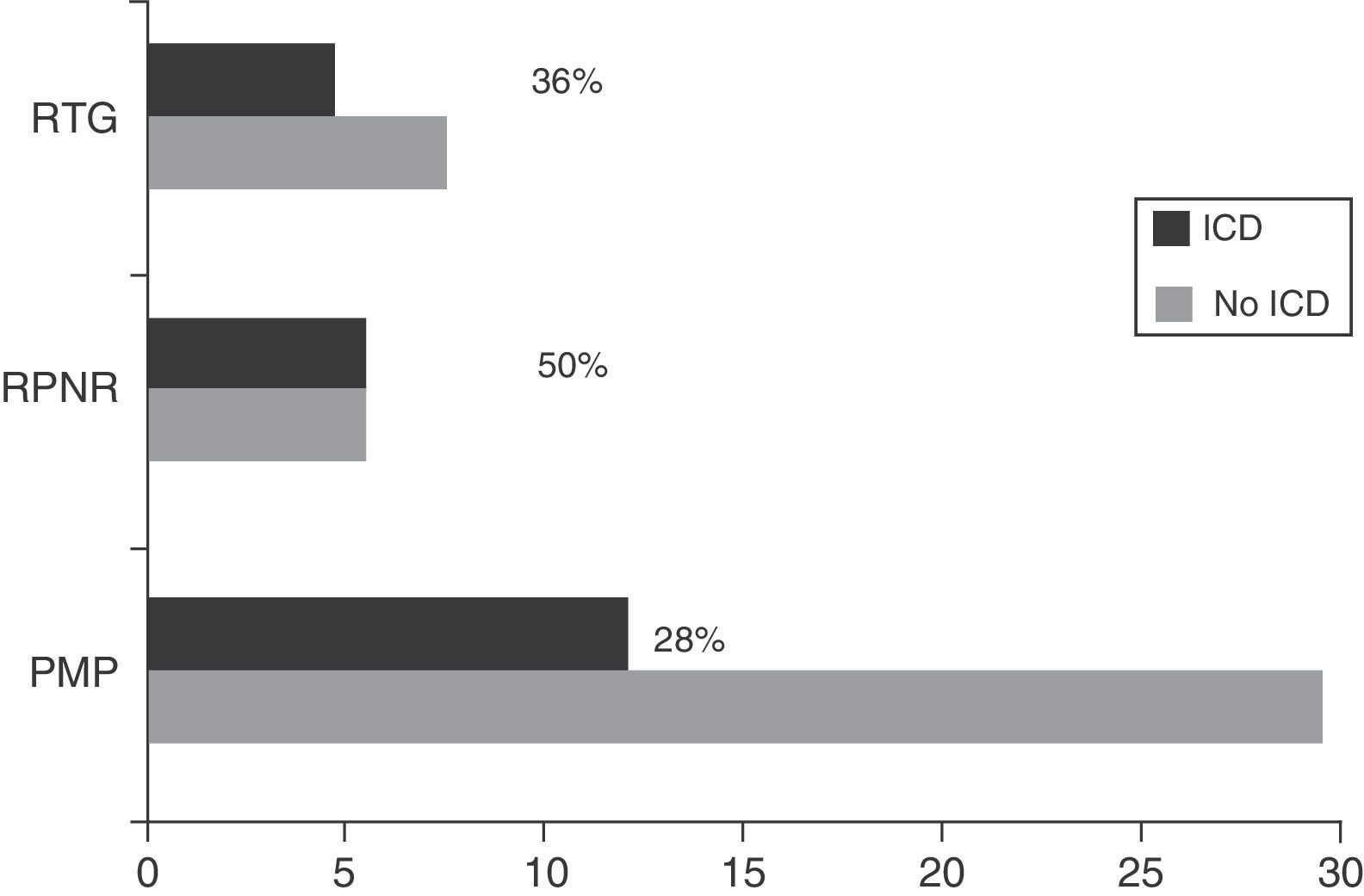

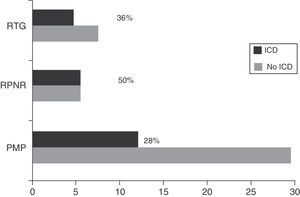

Regarding DRT, 21.74% of patients (n=25) received DA in monotherapy, 13.04% (n=15) LD in monotherapy, 47.83% (n=55) received combination therapy with both these drugs, and 29.6% (n=34) were de novo patients who had not started any treatment. Regarding other treatments, 46.1% (n=53) were treated with MAO-B inhibitors, 6.1% (n=7) received amantadine, and 15.7% (n=18) took antidepressants. Patients with some type of ICD were more frequently treated with DRT than those without (92.6% [n=25] vs 63.6% [n=56]; χ2=8.32; P=.004). Table 1 lists the drugs that patients were taking, broken down by the presence or absence of ICD. Regarding combination therapy, patients with some type of ICD were more frequently treated with DA+LD than patients with no ICD (59.3% [n=16] vs 29.5% [n=26]; χ2=7.87; P=.005). We conducted a subanalysis to compare the frequency of ICD by type of DA (pramipexole, ropinirole, and rotigotine) and found no significant differences (28%, 50%, and 36%, respectively; P=.384) (Fig. 2).

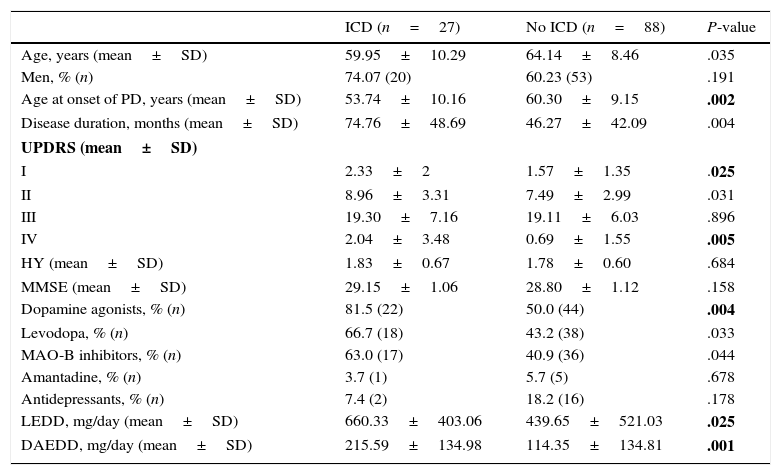

Demographic and clinical variables.

| ICD (n=27) | No ICD (n=88) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean±SD) | 59.95±10.29 | 64.14±8.46 | .035 |

| Men, % (n) | 74.07 (20) | 60.23 (53) | .191 |

| Age at onset of PD, years (mean±SD) | 53.74±10.16 | 60.30±9.15 | .002 |

| Disease duration, months (mean±SD) | 74.76±48.69 | 46.27±42.09 | .004 |

| UPDRS (mean±SD) | |||

| I | 2.33±2 | 1.57±1.35 | .025 |

| II | 8.96±3.31 | 7.49±2.99 | .031 |

| III | 19.30±7.16 | 19.11±6.03 | .896 |

| IV | 2.04±3.48 | 0.69±1.55 | .005 |

| HY (mean±SD) | 1.83±0.67 | 1.78±0.60 | .684 |

| MMSE (mean±SD) | 29.15±1.06 | 28.80±1.12 | .158 |

| Dopamine agonists, % (n) | 81.5 (22) | 50.0 (44) | .004 |

| Levodopa, % (n) | 66.7 (18) | 43.2 (38) | .033 |

| MAO-B inhibitors, % (n) | 63.0 (17) | 40.9 (36) | .044 |

| Amantadine, % (n) | 3.7 (1) | 5.7 (5) | .678 |

| Antidepressants, % (n) | 7.4 (2) | 18.2 (16) | .178 |

| LEDD, mg/day (mean±SD) | 660.33±403.06 | 439.65±521.03 | .025 |

| DAEDD, mg/day (mean±SD) | 215.59±134.98 | 114.35±134.81 | .001 |

After Benjamini–Hochberg correction, Pm≤.026.

DAEDD, dopamine agonist equivalent daily dose; LEDD, levodopa equivalent daily dose; HY, Hoehn and Yahr stage; MAO-B inhibitors, monoamine oxidase B inhibitors; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; UPDRS, Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale.

Statistically significant differences are shown in bold.

The univariate analysis of the sociodemographic and clinical variables (Table 1) showed statistically significant differences in age at onset, disease duration, scores on Parts I and IV of the UPDRS, and treatment with DA, LEDD, and DAEDD.

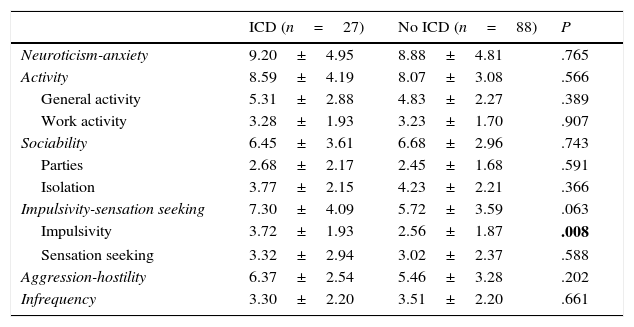

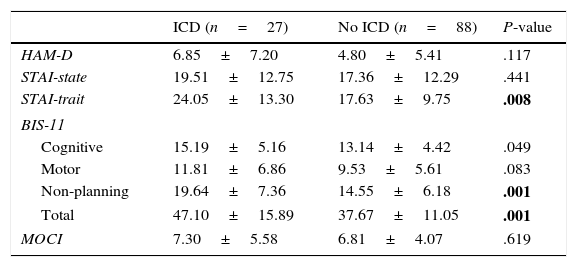

Regarding personality traits, patients with some types of ICD scored higher on impulsivity in the ZKPQ (P=.008). No differences were found between the 2 groups regarding the remaining personality traits (Table 2). As for the rest of the psychopathological variables, patients with ICD scored higher on trait anxiety (STAI-trait) and impulsivity (BIS: total and non-planning) (Table 3).

Scores on the different personality dimensions of the ZKPQ.

| ICD (n=27) | No ICD (n=88) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroticism-anxiety | 9.20±4.95 | 8.88±4.81 | .765 |

| Activity | 8.59±4.19 | 8.07±3.08 | .566 |

| General activity | 5.31±2.88 | 4.83±2.27 | .389 |

| Work activity | 3.28±1.93 | 3.23±1.70 | .907 |

| Sociability | 6.45±3.61 | 6.68±2.96 | .743 |

| Parties | 2.68±2.17 | 2.45±1.68 | .591 |

| Isolation | 3.77±2.15 | 4.23±2.21 | .366 |

| Impulsivity-sensation seeking | 7.30±4.09 | 5.72±3.59 | .063 |

| Impulsivity | 3.72±1.93 | 2.56±1.87 | .008 |

| Sensation seeking | 3.32±2.94 | 3.02±2.37 | .588 |

| Aggression-hostility | 6.37±2.54 | 5.46±3.28 | .202 |

| Infrequency | 3.30±2.20 | 3.51±2.20 | .661 |

After Benjamini–Hochberg correction, Pm≤.027.

Values are expressed as mean±SD.

Statistically significant differences are shown in bold.

Psychopathological features at the time of evaluation.

| ICD (n=27) | No ICD (n=88) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HAM-D | 6.85±7.20 | 4.80±5.41 | .117 |

| STAI-state | 19.51±12.75 | 17.36±12.29 | .441 |

| STAI-trait | 24.05±13.30 | 17.63±9.75 | .008 |

| BIS-11 | |||

| Cognitive | 15.19±5.16 | 13.14±4.42 | .049 |

| Motor | 11.81±6.86 | 9.53±5.61 | .083 |

| Non-planning | 19.64±7.36 | 14.55±6.18 | .001 |

| Total | 47.10±15.89 | 37.67±11.05 | .001 |

| MOCI | 7.30±5.58 | 6.81±4.07 | .619 |

After Benjamini–Hochberg correction, Pm≤.028.

Values are expressed as mean±SD.

BIS-11, Barratt Impulsiveness Scale; HAM-D, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MOCI, Maudsley Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory.

Statistically significant differences are shown in bold.

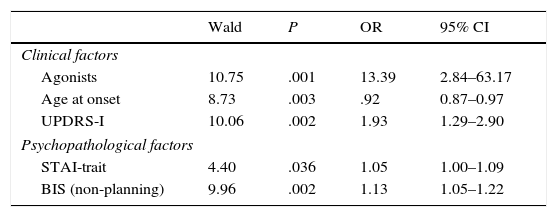

In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, the clinical factors associated with greater risk of having an ICD were younger age at onset of PD, higher scores on UPDRS Part I, and receiving DA. As for the psychopathological factors, trait anxiety (STAI-trait) and non-planning impulsivity were found to be significantly associated with ICD. Treatment with DA was the risk factor showing the strongest association with ICD, with an odds ratio of 13.39 (Table 4).

Logistic regression model showing the association between the different clinical and psychopathological variables and the presence of ICD.

| Wald | P | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical factors | ||||

| Agonists | 10.75 | .001 | 13.39 | 2.84–63.17 |

| Age at onset | 8.73 | .003 | .92 | 0.87–0.97 |

| UPDRS-I | 10.06 | .002 | 1.93 | 1.29–2.90 |

| Psychopathological factors | ||||

| STAI-trait | 4.40 | .036 | 1.05 | 1.00–1.09 |

| BIS (non-planning) | 9.96 | .002 | 1.13 | 1.05–1.22 |

BIS-11, Barratt Impulsiveness Scale; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ration; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; UPDRS, Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale.

Our study shows that ICDs are a frequent complication of PD. In line with previous studies, we found that treatment with DA was the risk factor most significantly associated with the presence of ICDs. Some clinical and psychopathological characteristics were also shown to increase the risk of ICD. More specifically, a younger age at disease onset and a greater level of anxiety and impulsivity at the time of assessment were the main factors.

According to some studies, ICDs are more frequent in patients with PD than in the general population.30 Prevalence data vary across studies.22,31 In our sample (23%), it was similar to that reported in 2 recent studies by Pontone et al.11 and Pérez-Lloret et al.32 In the DOMINION study, whose robust results are due to the large sample size, the prevalence was 14%.9 The frequency was higher in our study, possibly due to the fact that our sample was drawn from a tertiary care hospital where more complex cases and patients with earlier onset PD are treated. This may have had an impact on the frequency of ICD, resulting in a selection bias. We conducted a directed examination: we first used a semi-structured clinical interview and then a psychiatrist conducted a clinical assessment to confirm the results. This may also partially explain the differences in frequency between our sample and other published studies, where diagnosis was frequently based on self-administered questionnaires.33,34

Regarding the association between sex and the different types of ICDs, previous studies have shown that pathological gambling and hypersexuality are more strongly associated with men while binge eating and compulsive buying are more frequent in women.9,35 Our data replicate those reported for the general population and are compatible with the idea that ICDs are disorders associated with greater levels of impulsivity whose forms of expression vary depending on a number of factors, including culture, sex, and access to the stimulus (for example, casinos or gambling halls).36,37 These same factors may also explain the differences in the prevalence of certain types of ICD depending on the country where the sample was taken. In our sample, the most common types of ICDs were hypersexuality and binge eating, which coincides with the data reported by a French study.32 However, studies in Canada and the US have shown a higher frequency of pathological gambling and compulsive buying,9 whereas pathological gambling and hypersexuality were shown to be more prevalent in an Italian sample,8 and binge eating in a Mexican sample.37

The association between the presence of ICD and DRT has previously been described in the literature.9 There are several hypotheses that may explain this connection. The most widely accepted idea is that ICD appears as a consequence of the interaction between DRT and asymmetrical neuronal degeneration in the substantia nigra.38 Thus, the ventral region of the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNPC) projects to the dorsolateral caudate nucleus and putamen. These regions, which are involved in motor control, are particularly affected in PD.39 The amount of dopamine necessary to compensate for the deficit in this area may also act on the dorsal SNPC, where the neurons are spared.40 This region is close to the ventral tegmental area and innervates limbic structures. Therefore, overstimulation may lead to developing psychopathological symptoms, including ICDs.41 According to this hypothesis, the development of ICD would be linked to the interaction between treatment and disease progression rather than to PD itself. This idea is supported by several studies reporting similar frequencies of ICD in de novo PD patients receiving no treatment and healthy controls.7,42 In fact, in our study the percentage of patients receiving pharmacological treatment was higher in the ICD group.

Recent studies have examined the association between each presentation of ICD and the different DRTs.5 In line with our findings, other studies have indicated that ICDs are more frequent among patients receiving DA43; these drugs are considered one of the main risk factors for developing ICD. According to one hypothesis, this association may be explained by the greater affinity of these drugs for dopamine D3 receptors, which are mainly located in the limbic regions.44,45 In addition, these receptors have been linked to addiction mechanisms and have been suggested as therapeutic targets for substance use disorders.46 Some studies have also proposed that the route and dosage of DRT may have an impact on the risk of developing ICD. Other studies suggest that sustained release mechanisms, which enable continuous stimulation of the receptors, may contribute to developing ICD.37 Additionally, oral route DA have been associated with higher risk of ICD than transdermal DA (rotigotine).47 However, our study found no significant association with any type of DA. In any case, this was not among the purposes of the present study. Moreover, finding this association may have been due to a lack of statistical power. Our findings are in line with those reported by other studies but should be confirmed with research specifically designed to detect differences between the types of DA currently available.9

At the time of assessment, the patients with ICD scored higher on the UPDRS-I and showed greater trait anxiety and impulsivity (especially non-planning); these findings support the results of previous studies.6,14 Thus, greater prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and impulsivity has been correlated with greater prevalence of ICD. High anxiety levels may indicate that the serotonergic dysfunction present in PD may also play an aetiopathogenic role in the ICD in these patients.48 In addition, studies in other contexts have also established a link between impulsivity and serotonergic dysfunction.49

The present study is the first to analyse the influence of personality on ICD following the theoretical framework of the alternative 5-factor model developed by Zuckerman.50 Interestingly, although the patients with ICD scored higher than those without on the impulsivity scale of the ZKPQ, this dimension was not shown to be a risk factor for developing ICD in the multivariate analysis. We applied a personality model which assesses non-pathological dimensions of personality from a psychobiological perspective and discriminates between impulsivity and sensation seeking; this may justify the differences between our findings and those reported by studies applying other theoretical models.14 Not differentiating between these 2 aspects of impulsivity may have altered some results.22 Our findings show that greater impulsivity as a normal personality trait does not increase the risk of developing ICD in these patients. In line with previous hypotheses, DA treatment increases impulsivity in some patients, which in turn contributes to developing ICD.51

According to our data, several clinical and psychopathological factors present at the time of assessment are associated with increased risk of developing ICD in patients with PD. Likewise, personality traits are not indicative of a higher risk of developing these disorders. Further studies are necessary to determine other genetic and neuroendocrine factors that would help us screen for patients at greater risk of ICD.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Sáez-Francàs N, Martí Andrés G, Ramírez N, de Fàbregues O, Álvarez-Sabín J, Casas M, et al. Factores clínicos y psicopatológicos asociados a los trastornos del control de impulsos en la enfermedad de Parkinson. Neurología. 2016;31:231–238.

Part of this study was presented orally at the 65th Annual Meeting of the Spanish Society of Neurology.