Multiple cranial neuropathy refers to the involvement of multiple cranial nerves; its differential diagnosis is complex and includes several diseases.1,2

One possible aetiology of cranial neuropathy is neurolymphomatosis, which is defined as the infiltration of malignant lymphoid cells into peripheral, spinal, or cranial nerves or plexi, affecting several territories.3,4 Ninety percent of cases are associated with non-Hodgkin lymphomas and 10% with leukaemia, with a poorly defined incidence rate. It may appear as the initial manifestation of the (primary) oncological process.6,7 Primary neurolymphomatosis is a rare disease, with little information available on its form of presentation, course, diagnosis, and treatment, hence the interest of the present report.

We present the case of a 36-year-old man with no relevant medical history. Over the course of 3 months, he progressively developed symptoms of paralysis of the left abducens nerve, left peripheral facial palsy, which subsequently improved, and right peripheral facial palsy. At admission, the neurological examination revealed cranial nerve involvement (both abducens nerves and right facial nerve), with no other relevant finding. We observed no alterations in the initial assessment, which included neuroimaging studies (brain CT, contrast-enhanced MRI study of the brain and base of the skull), blood analysis (biochemistry, microbiological study, tumour markers, autoimmune study, angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE], vitamin B12, folic acid, thyroid hormones, total protein test, electrophoresis, serology tests, and rapid antigen test and polymerase chain reaction test for SARS-CoV-2), and testicular and thyroid ultrasound.

The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis after lumbar puncture showed lymphocytic pleocytosis (68cells/mm3, glucose level of 51mg/dL, and total protein level of 38.00mg/dL) but the remaining findings (cytobiochemistry, ACE, oligoclonal bands, microbiology study, Gram staining, cultures, and serology studies) were negative.

Most CSF lymphocytes presented atypical morphological characteristics under the light microscope, and a flow cytometry study showed an abnormal lymphocyte population expressing an immunophenotype compatible with leukaemia/T-lymphoblastic lymphoma.

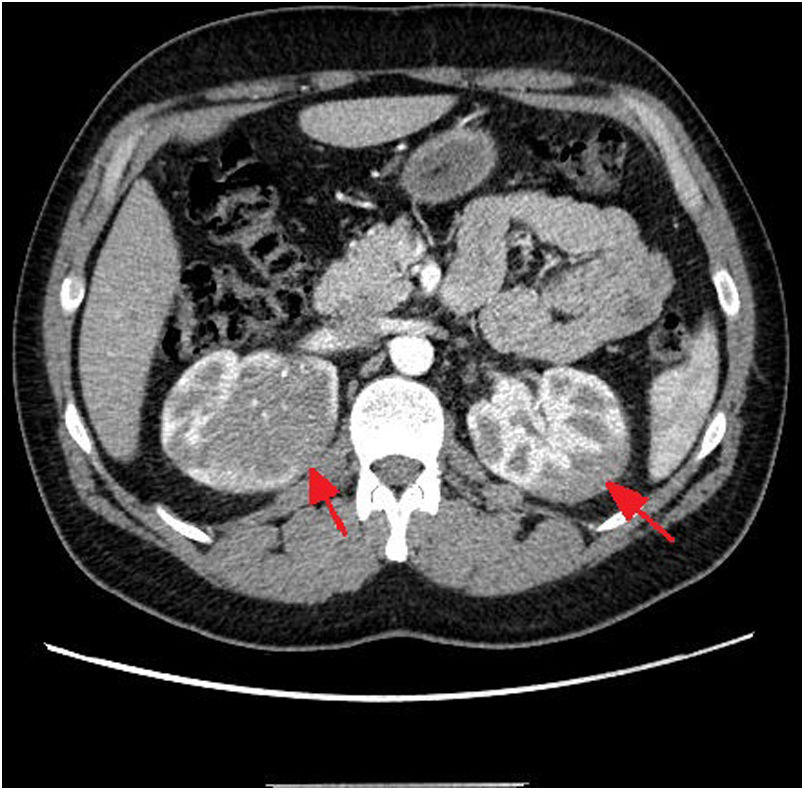

Considering these findings, we requested a chest, abdomen, and pelvis CT scan, which revealed an infiltrative renal mass (Fig. 1). A thick-needle biopsy and anatomical pathology study of a sample from the right renal mass confirmed infiltration of the renal parenchyma by an atypical lymphoid population with a high proliferative index, compatible with T-lymphoblastic lymphoma. Bone marrow biopsy showed mild infiltration (1.6%). The patient started treatment with dexamethasone at 6mg every 6 hours.

After the definitive diagnosis of T-lymphoblastic lymphoma, he started triple intrathecal therapy (TIT; methotrexate, cytarabine, and hydrocortisone) and intensive systemic chemotherapy following the 2011 protocol for acute lymphoblastic lymphoma.8

The patient responded well to treatment, with progressive improvement and eventually resolution of neurological symptoms. After one TIT cycle, CSF was acellular and flow cytometry revealed no disease. A follow-up CT scan showed almost complete resolution of the renal masses. The patient was transferred to the haematology department with no neurological symptoms.

Multiple cranial neuropathy requires good clinical integration and comprehensive assessment, with a broad differential diagnosis including multiple aetiologies (neoplastic, infectious, vascular, autoimmune).9 These symptoms may develop as a result of involvement at any anatomical location, from the brainstem to the peripheral nerves. Once the aetiology of the symptoms has been identified, the therapeutic approach to multiple cranial neuropathy consists of specifically treating the underlying condition.9

One of the least frequent aetiologies causing these symptoms is neurolymphomatosis. Neurolymphomatosis may precede the systemic disease in up to 25% of cases.6 As this manifestation is rare in malignant haematological disorders, its diagnosis is sometimes delayed and its incidence remains unknown.5 The clinical heterogeneity and non-specific brain imaging findings, together with the low yield of CSF analysis (lymphoma cells are detected in only 20%–40% of cases) may lead to underdiagnosis and delayed treatment of the underlying haematological disorder. Early treatment of the underlying condition leads to better prognosis.10

To date, there is no consensus on the optimal treatment; the literature mentions intensive chemotherapy with regimes intended to treat primary CNS lymphoma or relapsed lymphoma.5,6 In the case of neurolymphomatosis in T-lymphoblastic lymphoma,8,11 therapeutic strategies are the same as those used in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.12,13 Treatment should be based on consensus between experienced haematologists.

Regarding prognosis, the majority of patients respond well to initial chemotherapy, achieving good functional outcomes. However, long-term prognosis is poor, with a mean survival time of 10 months, which may be somewhat longer in the case of primary lymphomatosis.

FundingThis study received no funding of any kind.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.