Parsonage-Turner syndrome (PTS) or acute brachial neuritis is a rare cause of neuromuscular involvement in the shoulder, characterised by sudden onset of intense pain followed by muscle weakness and atrophy.1–3 Aetiology is heterogeneous; the immune-mediated response against the brachial plexus is considered an essential part of its aetiopathogenesis.4 Although cases have been reported of viral infection before onset of brachial neuritis, there are currently no published cases of PTS associated with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, as far as we are aware.

We describe the case of a 38-year-old man who developed PTS after severe bilateral pneumonia due to SARS-CoV-2 infection, who was admitted to the intensive care unit and treated with hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir/ritonavir, interferon beta, corticosteroids, and invasive mechanical ventilation. He was kept under deep sedation for several days, and received prone position ventilation on 2 occasions. As a relevant complication, we should mention septic shock secondary to ischaemic pancolitis due to SARS-CoV-2 infection, which was confirmed by anatomical pathology; the patient underwent ileostomy surgery.

During a visit to the rehabilitation department for functional recovery, the patient reported a 5-day history of continuous, progressive pain in both shoulders accompanied by a burning and tingling sensation, which disrupted sleep and partially remitted with conventional analgesics. He subsequently presented progressive muscle weakness in both shoulders, which limited his ability to perform activities of daily living.

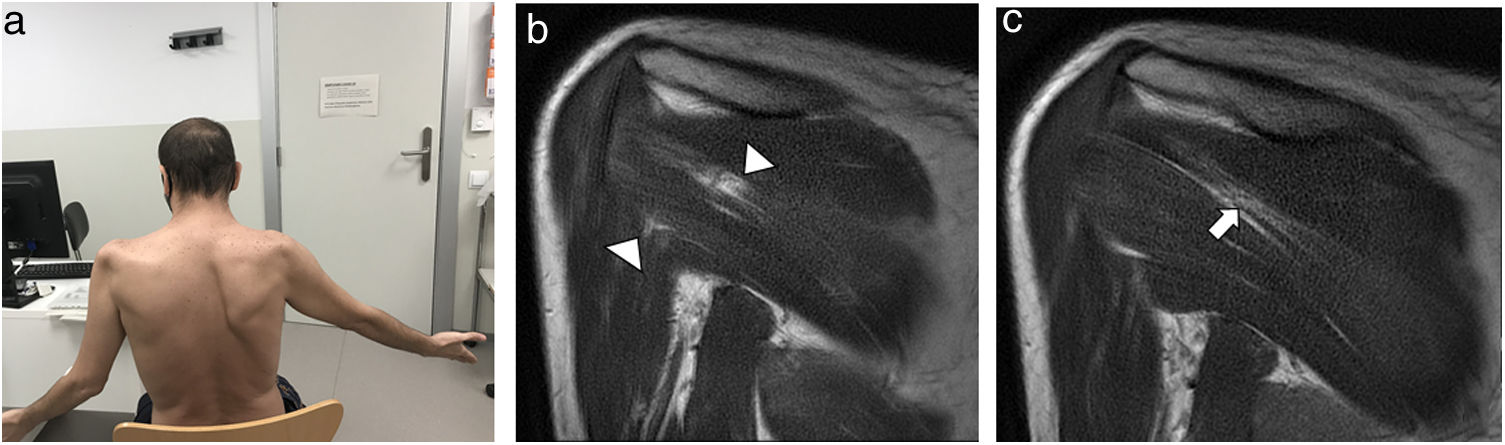

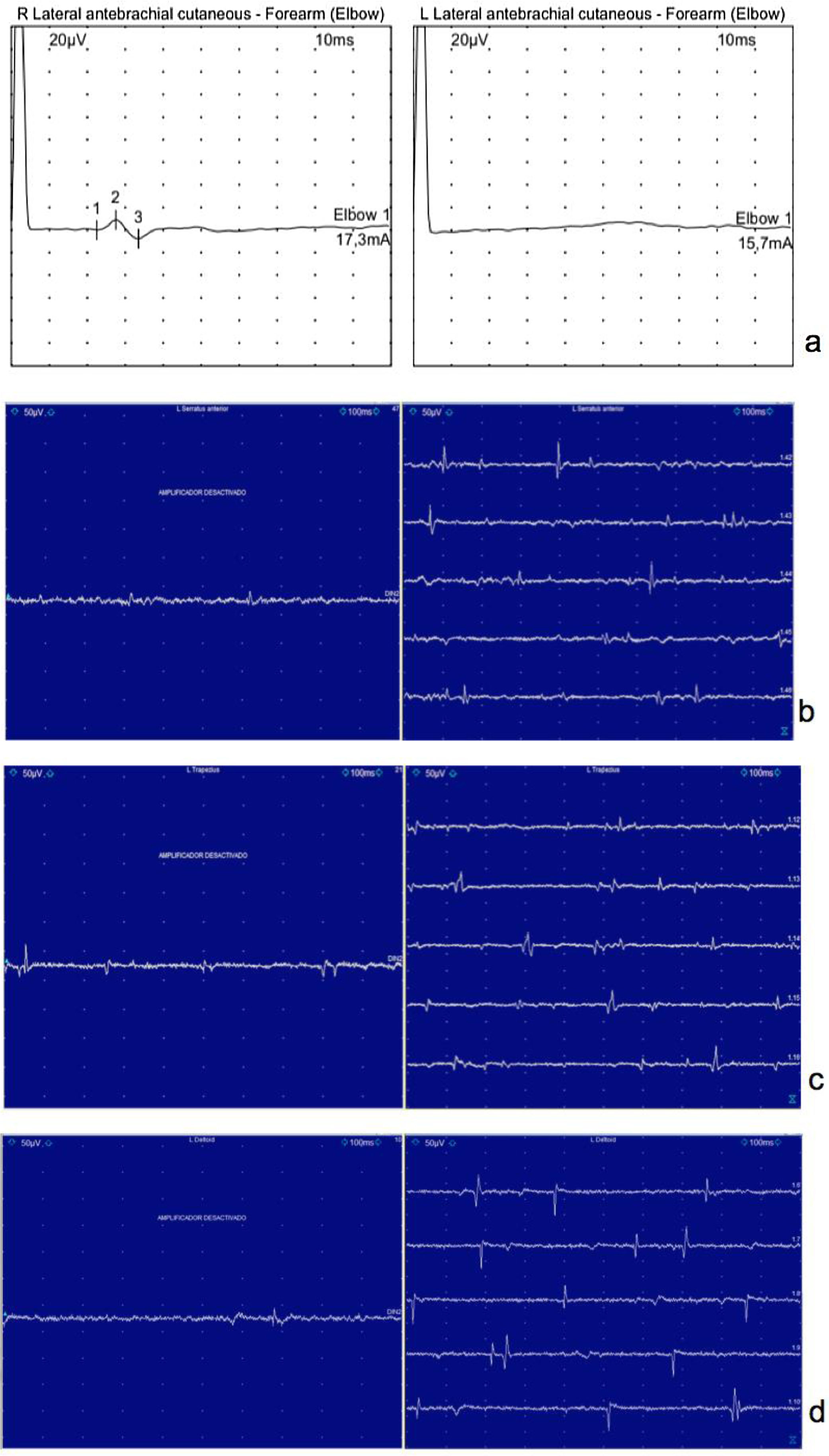

The physical examination revealed bilateral atrophy of the deltoid, supraspinatus, and infraspinatus muscles, right scapular winging, and hypoaesthesia in the deltoid area (Fig. 1a). An electrophysiological study revealed left brachial plexopathy with predominant involvement of the segment proximal to the upper trunk and distal to the C5 nerve root, and absence of sensory response in the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve, with signs of acute motor axon loss in the trapezius, deltoid, and serratus anterior muscles (Fig. 2). An MRI study revealed oedema of the bellies of both infraspinatus muscles and tendinosis of both supraspinatus muscles (Fig. 1b and c).

In view of these findings, he was diagnosed with PTS. The patient was treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs combined with long-acting opioids and prednisone. He also started rehabilitation therapy to improve balance and pain control.

PTS presents uncertain aetiology,1 predominantly affects men,1–3 and may be associated with viral infections, autoimmune mechanisms, immunisation, microtrauma, or surgical procedures.2 Twenty-five percent of patients may present systemic viral infection prior to symptom onset5,6 and almost one-third of patients present these symptoms bilaterally and symmetrically.

In terms of pathophysiology, sensitised lymphocytes have a special affinity for brachial plexus nerves, causing perineural oedema similar to that associated with urticaria.4 Our main hypothesis is that SARS-CoV-2 infection triggered an immune-mediated reaction involving the brachial plexus. Trauma may reasonably be ruled out as the cause of the symptoms, as the patient was only placed in the prone position on 2 occasions, presenting no pain or limitation of shoulder movement during hospitalisation. Numerous reports in the literature describe neurological symptoms and diseases in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection during the COVID-19 pandemic, including ischaemic cerebrovascular disease,7,8 polyneuropathies, and even necrotising encephalomyelitis attributed to a neuroinvasive effect in a patient with COVID-19.7,8

Diagnostic suspicion of PTS is established according to the symptoms reported by the patient and supported by the electrophysiological study, which in addition to enabling a better identification of the condition, also helps to rule out other possible causes and assess severity.9–11 MRI has been demonstrated to be useful in diagnosing PTS; the characteristic pattern includes neurogenic muscle oedema followed by atrophy of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and deltoid muscles, as well as fatty infiltration.1,12 All these findings were identified in our patient.

There is currently no specific treatment for this syndrome, as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are insufficient in the acute phase, and the use of opioids is necessary. Some studies use gabapentin for neuromodulation.13 Rehabilitation therapy is essential to improve joint mobility and strength and to control pain. Outcomes are heterogeneous and depend on pain intensity, the extent of plexus involvement, and whether presentation is bilateral or unilateral; all of these factors are predictors of recovery.14

FundingThe authors have received no funding for this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to thank Dr Alejandro Congo, radiologist at the musculoskeletal radiology unit, for providing the images.

Please cite this article as: Alvarado M, Lin-Miao Y, Carrillo-Arolas M. Síndrome de Parsonage-Turner postinfección por SARS-CoV-2: a propósito de un caso. Neurología. 2021;36:568–571.