A significant percentage of patients with stroke will experience recurrence.1,2 Some of these cases of recurrence may arise due to resistance to antiplatelet treatment.3 We describe the case of a patient who suffered several recurrent strokes, a situation attributed to insufficient analysis of risk factors; however, the possibility of resistance to antiplatelet treatment was not examined.

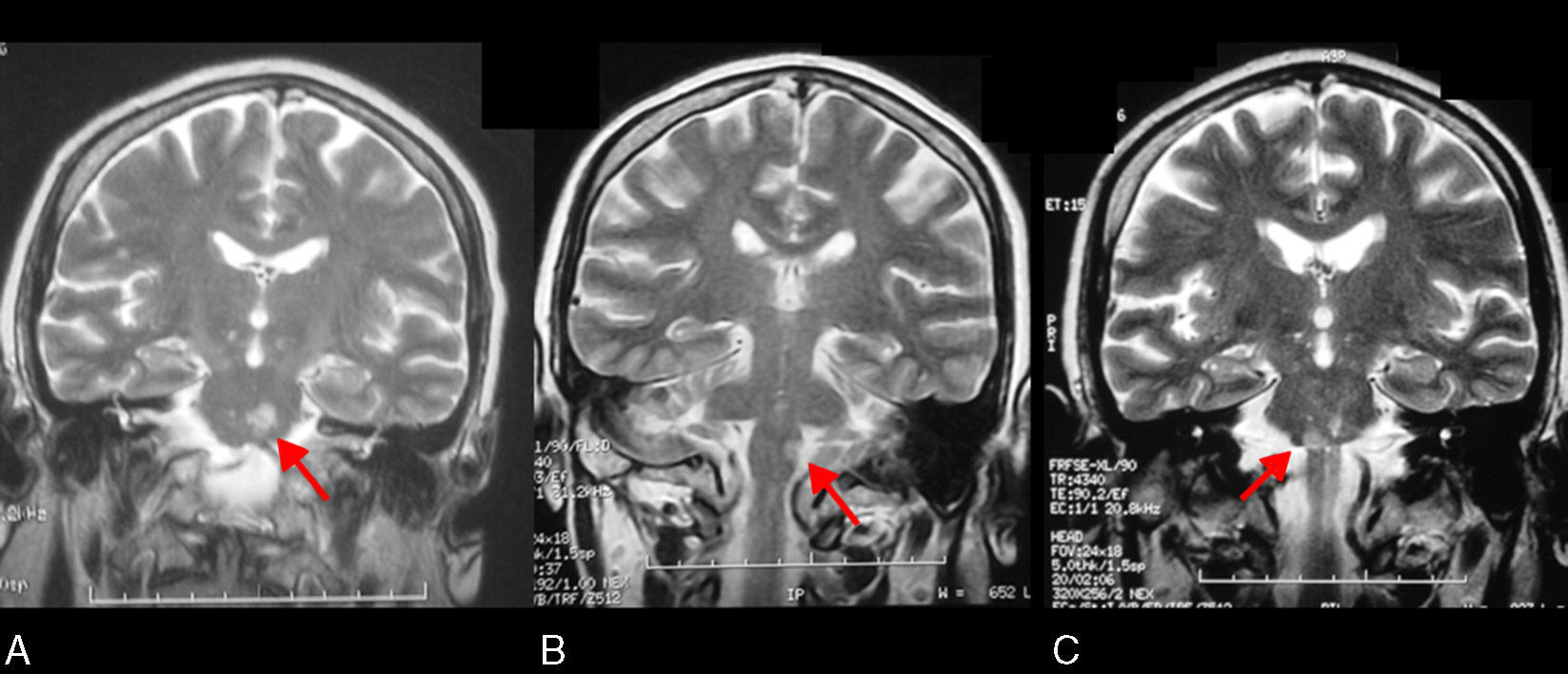

Our patient was a 51-year-old woman who was hospitalised for dysarthria in October 2006. Her cardiovascular risk factors comprised heavy smoking habit (2.5 packs of cigarettes daily), diabetes (with diabetic retinopathy), arterial hypertension, and dyslipidaemia. There was no other relevant family or personal history. She was treated with atorvastatin 20mg, insulin, and acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) 500mg. At time of admission, the patient displayed mild right-sided hemiparesis and dysarthria. Cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a left pontine stroke (Fig. 1A). The neurovascular study (MRI angiography and carotid duplex ultrasound) showed clinically diffuse silent carotid atheromatosis causing stenosis of 60% on the right side. Cardiology study results were normal. A blood panel revealed high triglyceride levels (190mg/dL) and high glycaemia (265mg/dL). The stroke was attributed to microangiopathy and the patient's drug regimen was adjusted by adding clopidogrel and increasing the statin dose to 80mg daily.

In September 2008, the patient came to the emergency department because of right-sided hypoaesthesia. Neurological examination revealed facio-brachio-crural hypoaesthesia preceded by mild paresis. Duplex carotid ultrasound showed bilateral carotid atheromatosis similar to that in the previous study. Transcranial duplex ultrasound yielded normal results. The blood count, including microbiology study and antiphospholipid antibodies, showed no abnormalities. Cranial MRI revealed a left medullary stroke (Fig. 1B). The patient remained on clopidogrel; low molecular-weight heparin (nadroparin calcium 0.6mL SC daily) was added and later withdrawn after the cardiology study. The transthoracic ultrasonography in that study revealed ventricular hypertrophy and discrete left atrial enlargement. A routine CT angiography showed diffuse atheromatosis with no other alterations.

In April 2011, the patient was hospitalised for left hemiparesis. A neurological examination recorded exacerbation of initial dysarthria, left hemiparesis (3/5 in arm, 2/5 in leg), mild right hemiparesis, and bilateral Babinski sign. Cranial MRI revealed a right pontine stroke (Fig. 1C), and CT angiography indicated diffuse atheromatosis. High blood pressure and hyperglycaemia were also recorded while the patient was hospitalised. Once again, the diagnostic impression was microangiopathy plus poor control over cerebrovascular risk factors, and the patient continued to take antiplatelet drugs.

In November 2011, the patient stopped taking all drugs due to difficulty swallowing and was admitted due to poor clinical status. A neurological examination yielded similar results to previous ones, in addition to severe dysphagia. The patient could walk using supports and required assistance with most activities, including basic tasks. In light of the recurrent strokes and worsening clinical state, doctors suspected a neoplastic aetiology and performed a full work-up to rule out that suspicion. The haematology department completed a platelet study that yielded the following results: Platelet Function Analyser (PFA) collagen/epinephrine test 94seconds (85-165), PFA collagen/ADP 86seconds (71-118), and PFA P2Y 71seconds (0-106). These tests did not show an antiplatelet effect occurring with either ASA or clopidogrel, even after raising the dose to 150mg/day. The patient began treatment with cilostazol.

Earlier studies have described lacunar strokes as being the most frequently responsible for pure motor hemiparesis. Their main localisations are the internal capsule and the pons, as is the case in our patient.1 Recurrence in lacunar stroke entails progressive motor and cognitive impairment. These patients will come to be dependent on others for activities of daily living, and this situation is costly. Today, tight control over cerebrovascular risk factors and use of antiplatelet drugs are the pillars of treating lacunar stroke. However, despite the benefits of antiplatelet drugs, many patients experience recurrent strokes.2–4 This phenomenon may be explained in part by resistance to antiplatelet treatment,4 defined as failure by the agent to block its target even when used at the correct dosage.5,6 In our hospital, platelet function is measured using the PFA collagen/epinephrine and PFA collagen/ADP tests for ASA and the PFA P2Y test for clopidogrel. In our patient, results on all tests were below the threshold for an antiplatelet effect. Higher doses of ASA (≥325mg/day) and strict adherence to treatment may successfully overcome resistance to ASA in some patients.5 Maintaining clopidogrel at 150mg/day is an option for patients who are poor responders.6 Although both approaches were used in our case, we observed no response. On the other hand, results from the SPS3 study, showing that antiplatelet bitherapy with ASA and clopidogrel was not superior to ASA in monotherapy in patients with lacunar stroke, influenced the decision to not administer this treatment to our patient.7

We believe that this case illustrates the importance not only of strict control over cerebrovascular risk factors, but also of administering personalised antiplatelet drugs. Measuring the response to antiplatelet drugs is an option in clinical practice that may help establish effective antithrombotic treatment, and should be carried out at least in those patients with recurrent cerebral infarcts.

Please cite this article as: Delgado MG, Corte JR, Sáiz A, Calleja S. Ictus lacunar recurrente por resistencia al tratamiento antiagregante plaquetario: hacia la necesidad de una terapia antitrombótica individualizada. Neurología. 2015;30:376–378.