Hypercoagulability is a documented manifestation of SARS-CoV-2 infection, especially in more severe cases in which patients are admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). Its aetiopathogenic mechanisms are yet to be fully understood, although it is reported to cause endothelial dysfunction, excess thrombin, and inhibition of fibrinolysis.1 The most frequent thrombotic complications include pulmonary thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, and ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke, which manifest 1-2 weeks after diagnosis.2 Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVT) has been described in small case series,1,3 but it has not been observed in larger registries of hospitalised patients with COVID-19.4,5 The clinical manifestations of CVT are variable (from headache, focal symptoms, and epileptic seizures to altered level of consciousness6), which may lead to underdiagnosis or diagnostic delay in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, as COVID-19 may also present with neurological manifestations.4,5,7 We describe the case of a patient with CVT secondary to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Our patient was a 36-year-old woman with history of bronchial asthma and perinatal hypoxic encephalopathy with mild disability. She attended the emergency department due to progressive hypoactivity and bed confinement at home, where she had self-isolated for 8 days after receiving positive results for SARS-CoV-2 in a PCR test of nasopharyngeal exudate; the patient reported no other symptoms. Oxygen saturation at hospital arrival was 89% and did not improve with high-flow oxygen therapy; the patient subsequently underwent orotracheal intubation and was admitted to the ICU. A chest radiography revealed bilateral interstitial pneumonia. A blood analysis showed lymphocytopaenia and D-dimer level of 25 830 ng/mL.

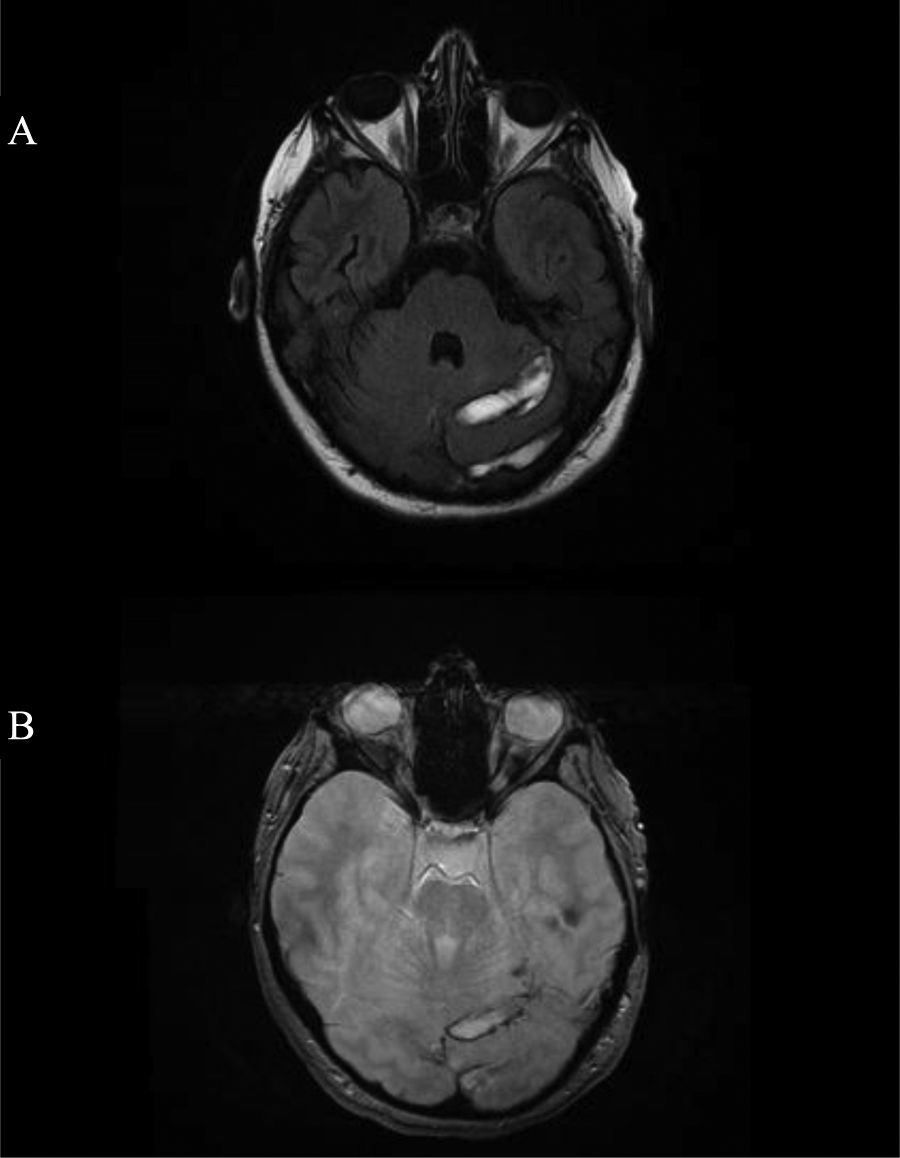

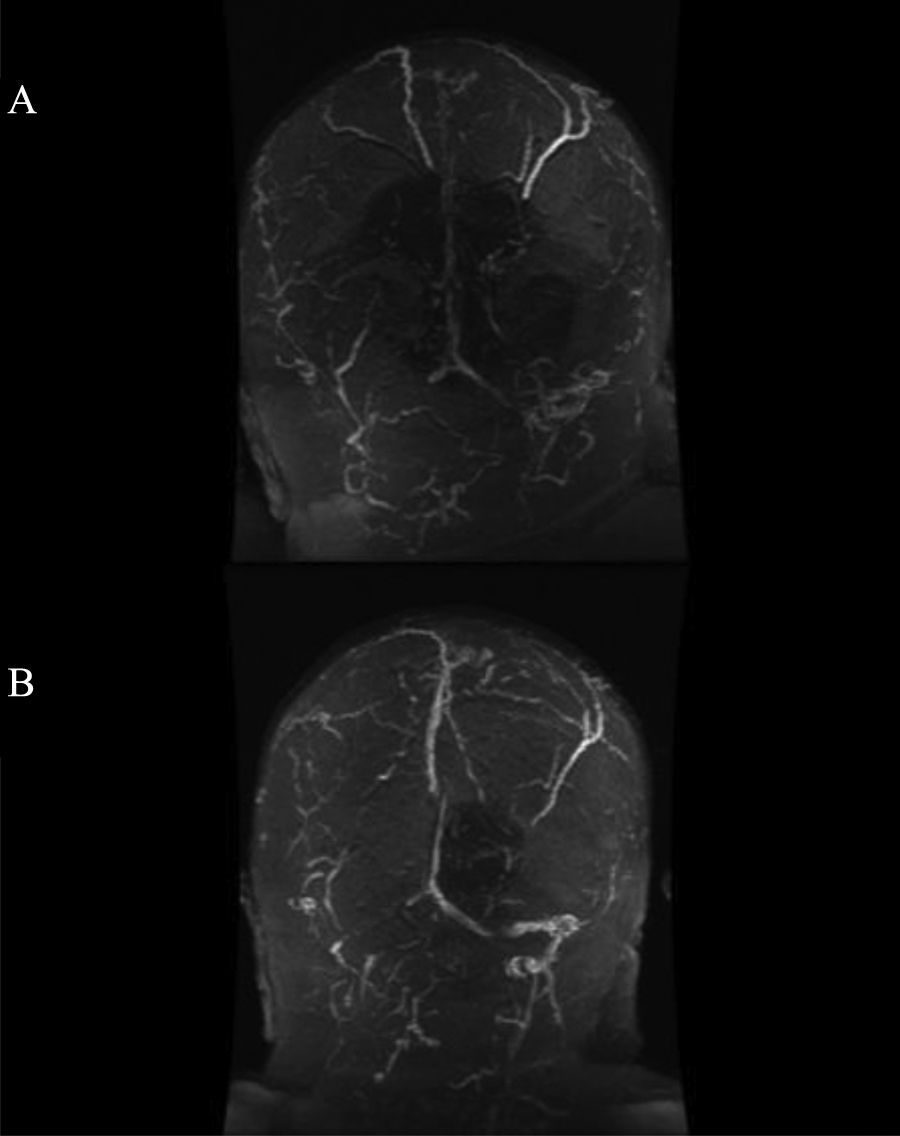

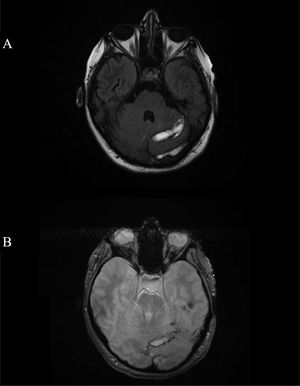

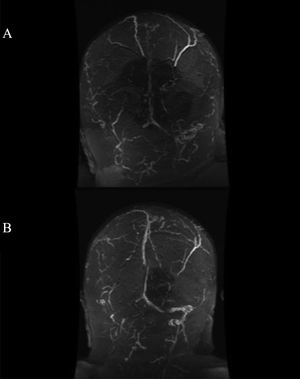

On day 11 of hospitalisation, we conducted a neurological wake-up test; the patient presented spontaneous eye opening with mild motor dysphasia and right-sided, predominantly brachial, hemiparesis. An emergency head CT scan with contrast showed filling defects in the left superior sagittal, straight, transverse, and sigmoid venous sinuses associated with the CVT, and infarctions in the left frontotemporal region and cerebellar hemisphere, with haemorrhagic areas. We started treatment with low–molecular weight heparin and requested a brain MRI scan and a brain MRI angiography, which confirmed the diagnosis (Fig. 1 and 2). A hypercoagulability study yielded positive results for lupus anticoagulant. Considering the presence of haemorrhagic infarction and the available evidence,8 we decided to maintain anticoagulant treatment with dabigatran. Over the following weeks of hospitalisation, the patient presented a slowly progressive improvement with respiratory stability; she then started rehabilitation treatment, which improved the hemiparesis and achieved partial recanalisation of the CVT, which was followed up by MRI at 2 months. No other complications were observed.

Brain MRI angiography revealing extensive venous thrombosis affecting the superior longitudinal, transverse, and sigmoid sinuses of both hemispheres (A). One-month follow-up image (B) showing partial recanalisation of the left superior longitudinal, transverse, and sigmoid sinuses after treatment with dabigatran.

We believe that the CVT in our patient was a complication of the SARS-CoV-2 infection, which causes systemic inflammation and promotes a hypercoagulable state. It should also be noted that in these patients, the dehydration induced by the infection and blood stasis caused by prolonged immobility may also participate as additional causal mechanisms.1 Furthermore, the laboratory study revealed antiphospholipid antibodies, of uncertain significance and transient nature, which have also been reported in previous articles.10 In our case, we opted for oral anticoagulation with dabigatran due to its lower rate of intracranial haemorrhagic complications and its efficacy in the treatment of CVT,8 as our patient already presented haemorrhagic complication of the cerebellar infarct, with no other complications and good radiological outcomes.

Despite the high prevalence of thrombotic complications in patients with COVID-19, few cases of CVT have been reported to date.1,3 Large Spanish series4,5 identified no cases of CVT during the first wave of COVID-19. In our case, although our patient attended the emergency department with progressively reduced consciousness and very elevated D-dimer levels,9 it was not until respiratory stability was achieved that we were able to establish a diagnosis and start treatment. This form of presentation and diagnostic delay may support the hypothesis that CVT is underdiagnosed in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection.2

Therefore, we recommend that the possible presence of intracranial thrombotic complications be considered in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection presenting reduced level of consciousness or presence of subacute or progressive focal symptoms not limited to a defined arterial territory.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

Please cite this article as: Almarcha-Menargues ML, Martínez-Martínez MM, Fernández-Travieso J. Infección por SARS-CoV-2: posible infradiagnóstico de trombosis de senos venosos cerebrales. Neurología. 2021;36:575–576.