Short cognitive tests are routinely used in clinical practice to detect and screen for cognitive impairment and dementia. These cognitive tests should meet minimum criteria for both applicability and psychometric qualities.

DevelopmentThe Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is the most frequently applied short cognitive test, and the article introducing it remains a milestone in the history of medicine. Its main advantages are its widespread use and the extensive empirical evidence that supports it. However, the MMSE has important shortcomings, including lack of standardisation, its lack of suitability for illiterate subjects, the considerable effect of socio-educational variables on results, and its limited effectiveness for detecting cognitive impairment. Lastly, since the test is copyright-protected, using it is necessarily either costly or fraudulent. Newer available instruments do not share these shortcomings and have demonstrated greater diagnostic accuracy for detecting cognitive impairment and dementia, as well as being more cost-effective than the MMSE.

ConclusionIt is time to acknowledge the MMSE's important role in the history of medicine and grant it a deserved and honourable retirement. Its place will be taken by more effective instruments that require less time, are user-friendly and free of charge, can be applied to all individuals, and yield more equitable outcomes.

Los test cognitivos breves (TCB) son instrumentos de uso habitual en la práctica clínica para la detección y el cribado del deterioro cognitivo y demencia. Los TCB deben reunir unas características de aplicabilidad y psicométricas mínimas.

DesarrolloEl Mini-Mental es el TCB más utilizado y el artículo en el que se describe es un hito en la historia de la Medicina. Su principal ventaja es la amplia difusión de su uso y el extenso soporte empírico que la apoya. No obstante, el Mini-Mental tiene numerosas e importantes limitaciones, fundamentalmente la falta de estandarización, el no poder ser aplicado a analfabetos, la gran influencia en sus resultados de las variables socioeducativas y la discreta utilidad para la detección de DC; además, este instrumento está protegido por copyright por lo que su uso es gravoso o fraudulento. En la actualidad, hay TCB disponibles que no cuentan con estas limitaciones y que han mostrado una mayor utilidad diagnóstica e incluso un mayor coste-efectividad que el Mini-Mental en la detección de deterioro cognitivo y demencia.

ConclusiónEs hora de reconocerle al Mini-Mental el importante papel que ha desempeñado en la historia de la Medicina y concederle una merecida y honrosa jubilación, dando paso a instrumentos más breves, fáciles y baratos, que puedan ser aplicados libremente a todos los individuos y que sean más eficientes y justos.

Short cognitive tests (SCTs) are instruments used frequently and routinely in clinical practice to detect and screen for patients with cognitive impairment (CI) or dementia (DEM), but this is not their only function. They are also used for follow-up and to assess the patient's response to treatment.1 In any case, rather than being diagnostic tools, they are merely ‘cognitive thermometers’ or ‘brain stethoscopes’,2 that is, another clinical evaluation resource that lets doctors assess cognitive function rapidly. They also help physicians find alarm signs that call for a more detailed cognitive evaluation.

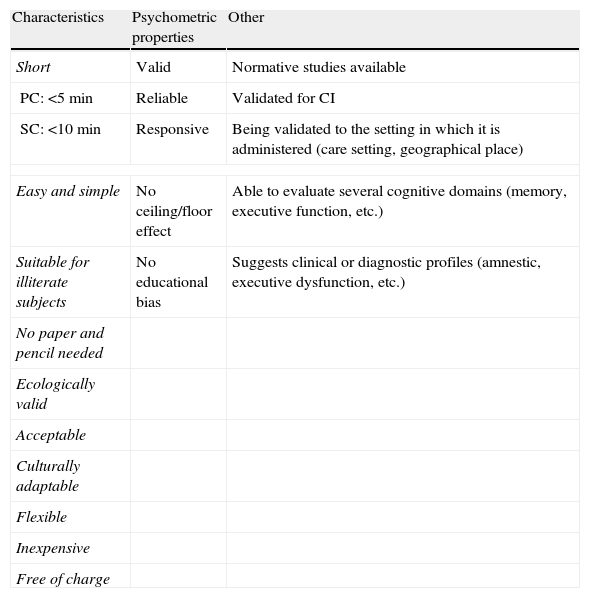

Characteristics and conditions of short cognitive testsThe ideal SCT1 should present a specific set of characteristics (Table 1). Of these, the most crucial is short administration time, a subjective concept that depends on the setting in which the test is used. In a specialist clinic, an administration time of 10minutes may be acceptable whereas in a primary care consultation, an SCT requiring more than 5minutes would be too long considering the mean length of consultations in most European countries.3 SCTs should also require minimal instrument use and be straightforward and easy to administer and score. Assessment should be direct, objective and unequivocal,4 with no need for complex instructions, devices, tables, or calculations. SCTs should also be acceptable, user friendly and ecologically valid,5 meaning that they should not result in any discomfort, refusal, or distress on the part of the patient being assessed. Their scope should be limited to responses or actions related to the patient's daily life. A good SCT should be applicable to all and allow physicians to evaluate all subjects, regardless of their personal traits, skills, or sociodemographic, ethnic, or cultural characteristics. Other qualities to consider include cultural adaptability6 and flexibility, which would make tests easier to use in different geographical and language settings, and different evaluation circumstances (at home, the doctor's office, or a hospital). Finally, the ideal SCT should be free to use6 and not subject to patent or copyright restrictions, and inexpensive7 in terms of administration and the cost of materials or expendables.

Qualities and characteristics of the ideal short cognitive test.

| Characteristics | Psychometric properties | Other |

| Short | Valid | Normative studies available |

| PC: <5min | Reliable | Validated for CI |

| SC: <10min | Responsive | Being validated to the setting in which it is administered (care setting, geographical place) |

| Easy and simple | No ceiling/floor effect | Able to evaluate several cognitive domains (memory, executive function, etc.) |

| Suitable for illiterate subjects | No educational bias | Suggests clinical or diagnostic profiles (amnestic, executive dysfunction, etc.) |

| No paper and pencil needed | ||

| Ecologically valid | ||

| Acceptable | ||

| Culturally adaptable | ||

| Flexible | ||

| Inexpensive | ||

| Free of charge | ||

SC: Specialist hospital care; PC: primary care; CI: cognitive impairment.

Furthermore, an SCT meeting all the usability requirements mentioned above would still be insufficient if it lacked the minimum psychometric qualities, namely validity and reliability. There are many types of validity. Criterion validity is usually measured by calculating sensitivity (SE) and specificity (SP), although this is probably the least appropriate formula as sensitivity and specificity values have many limitations. They depend on prevalence, and SE is calculated using only affected patients and SP, unaffected patients. In any case, a good SCT should present SE and SP values greater than 0.80. A more pragmatic way to measure criterion validity is discriminability, which measures an instrument's ability to differentiate healthy subjects from affected ones. This measurement can be estimated in a global way using the area under the ROC curve, and in a specific way for a certain cut-off point by measuring diagnostic agreement (Kappa index) or correct classification rate. Values are considered acceptable when they are equal to or higher than 0.70 or 0.80, respectively. Another essential aspect of an SCT is test-retest and interrater reliability. Both types are measured using the intraclass correlation coefficient and values equal to or higher than 0.80 should be considered acceptable. Other desirable psychometric characteristics are responsiveness, lack of floor and ceiling effects,4 and delivery of results that are free from biases and influences derived from demographic, educational, and cultural variables.4–6,8,9

Additional qualities that support the value of an SCT are presence of normative studies7,9 and specific validation studies performed in the geographical and care setting in which the test is applied, especially population and primary care studies.6,10 From the clinical point of view, the SCT should be specifically validated for CI5,8 and not only for DEM, since in clinical practice it is more important to detect and study CI than just DEM.11 Finally, SCT should permit physicians to evaluate multiple cognitive domains, including episodic memory and executive function at the very least.5 Their results should suggest an impairment profile indicating concrete aetiologies (amnestic profile, executive dysfunction profile, etc.).4

ProcedureThere are countless SCTs and it is difficult to identify one that is able to fulfil the wide array of qualities that the ideal SCT should include. Without entering into its characteristics, the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)12 is unquestionably the most frequently used SCT.

Mini-Mental State ExaminationThe MMSE was originally designed and created to systematically and quantitatively evaluate and describe the mental state of hospitalised psychiatric patients and to monitor any changes in this state.13 The MMSE takes between 7 and 10minutes to complete and contains items that assess orientation, registration, attention and calculation, recall, language, repetition, reading, writing, comprehension of commands, and drawing. Scores range between 0 and 30 points. It has no original items; according to its author, “I included those items that had been clinically useful to me and that could be scored with little interpretation”.14 Some of those items had already been included in other instruments (for example, the Blessed scale15).

The MMSE has been translated into more than 50 languages and we also find a wide variety of versions which can be adapted to fit very diverse testing conditions (blind patients, etc.). Different adapted versions are available in Spain,16,17 and the most popular form is named MiniExamen Cognoscitivo.18 There have been several normative population studies19,20 and a telephone interview version has been validated recently.21

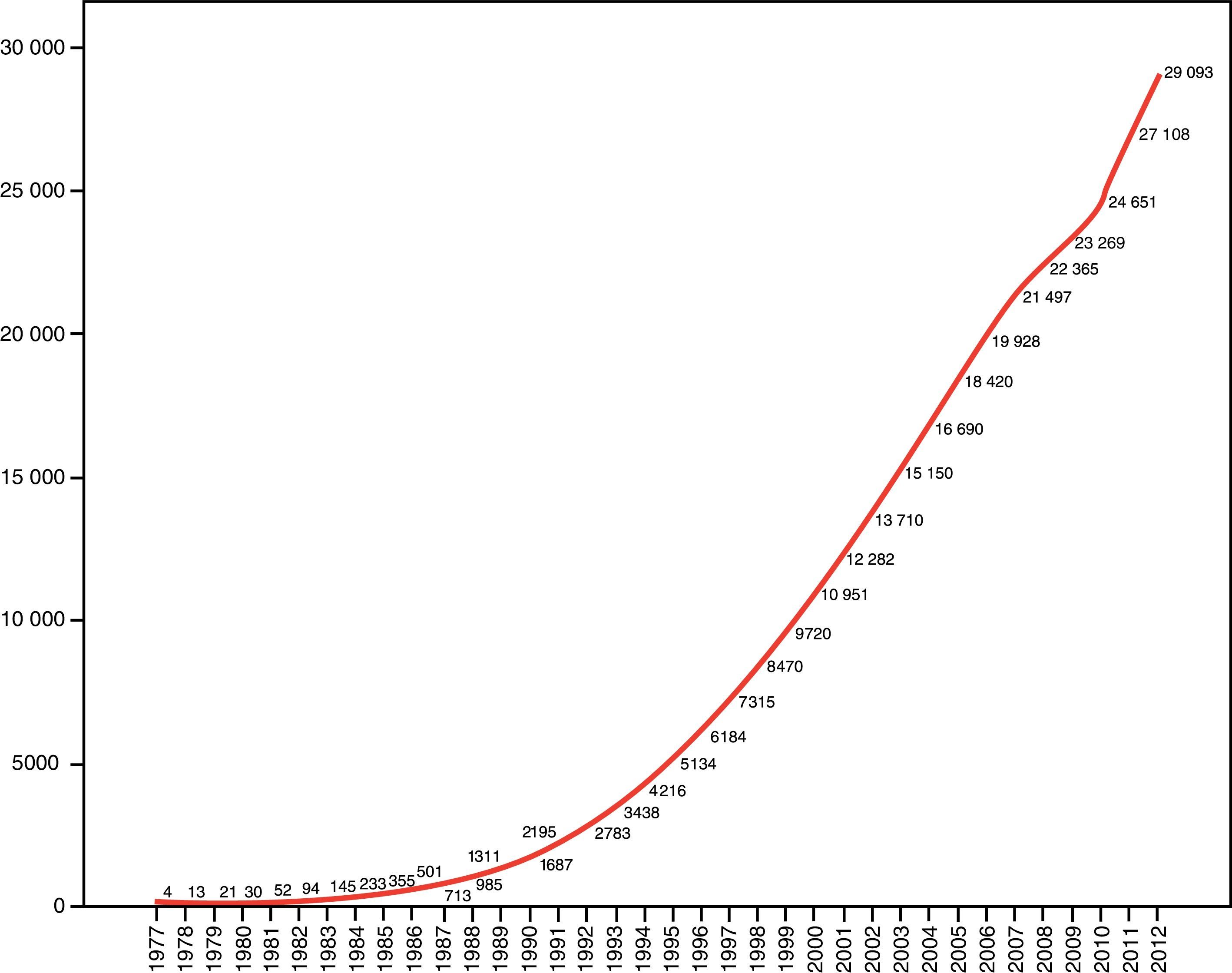

The original article on the MMSE 12 is probably the most frequently cited reference in health science literature,22 with a total of 29057 citations as of 31 December 2012 (Fig. 1) (Journal Citation Reports®). This places the article far ahead of such legendary articles in the history of medicine as Watson and Crick's description of the structure of DNA (4705 citations)23 or Prusiner's article describing prions (2641 citations).24 Due to its diffusion and popularity, MMSE is used as an SCT; as a result, it also serves for patient classification,25 definition of inclusion criteria in clinical studies and trials, and even for defining the criteria and limits on access to treatment and social and healthcare resources.26 This last issue is very controversial and has been subject to extensive criticism and even legal action.

The MMSE is an instrument recommended by the main clinical practice guidelines (for example, those published by the AAN,27 NICE,28 or Canadian and Spanish guidelines29,30). At present, it is routinely used by most old-age psychiatrists in the USA and Canada31 and by more than 90% of the neurologists in England.32 The first one to be surprised by the success and diffusion of the MMSE was the author himself, who acknowledged that “It continues to amaze us that the particular combination of items in the MMS, conceived in one night, is so useful to clinicians and epidemiologists in many countries”.14

Do the characteristics and qualities of the MMSE justify its universal and undisputed use? Does the MMSE satisfy all the needs that an SCT should cover?

Advantages and disadvantages of the MMSEThe main advantage of MMSE is its widespread use and the large amount of available data, which makes it easier to find standards for comparison in a wide variety of settings and circumstances. MMSE is a relatively user-friendly instrument that can be administered and evaluated by non-qualified personnel and it is taught in most academic institutions.33 Its structure, administration process, and interpretation are therefore almost universally understood, which has facilitated its becoming implicitly accepted as a measurement unit and benchmark for evaluating CI and DEM severity. The MMSE structure ensures the evaluation of several cognitive domains34 and its scoring system has been assimilated as a measure of global cognitive functioning. This makes it easier to compare different studies and subjects, and also to follow up on and assess response to treatment.

Aside from these unquestionable advantages, the MMSE also possesses many significant limitations and weaknesses. These have become much more apparent as increasing demand has been placed on SCT and more instruments able to satisfy those requirements have been created.

Structural problemsThe MMSE was not specifically created to screen for DEM. This explains why most of its scoring items are related to orientation (10 points), and language (8 points); only 3 of its 30 points assess memory. Memory is the main cognitive domain to be affected in early stages of the most frequent types of DEM. Memory impairment has been a requirement for all diagnostic criteria for CI and DEM published to date. Executive functions are also under-represented and the MMSE therefore shows low sensitivity to frontal lobe dysfunction. This test contains several items that do not increase the discriminant ability of the battery, especially in cases of mild CI or DEM. The full version of MMSE is no more accurate than a selected array of its items or one of its short forms.35–37 The most discriminatory items for initial stages of impairment, and therefore the most useful for screening purposes, are recall and time orientation.38

Lack of a standard administration procedure is a long-recognised problem39 that seriously affects reliability.32 In this regard, the most relevant point, although not the only one, is the words used in the recall task.32 The words to be repeated are not specified by the original instructions12 and they are chosen by the examiner. This is a significant disadvantage since word recall is sensitive to the words used and it is influenced by traits such as frequency of use, semantic category, concept specificity, phonetic difficulty, number of syllables, imaginability, or familiarity. As a result, some words are recalled more easily than others.40 Other items that vary are the drawings used, the sentence to be repeated, the method of performing the calculation, and whether or not the calculation task is replaced with backward spelling.

One important limitation of MMSE is that it cannot be administered to illiterate subjects as 2 of its items involve reading and writing. Another limitation is the inclusion of a task requiring paper and pencil (copying a drawing). This is not due to the difficulty of completing this task, but because tasks involving paper and pencil, although theoretically accessible to illiterate or undereducated subjects, may cause reactions of aversion and rejection in this group of patients who will consequently perform poorly. Illiteracy, far from being eradicated in our society, remains a global problem; more than 750 million illiterate people were counted in 2010.41 This situation is not limited to underdeveloped countries and is even present in the most developed ones. For example, it is estimated that up to 3% of the adult population in the USA, or about 7 million people, is illiterate.42 In Spain, due to the historical circumstances of the past century, the illiteracy rate in people older than 65 years is very high (214 per 1000 inhabitants).43 We should also consider the emergence of another type of relative illiteracy whose frequency is increasing. Deriving from migration and tourism, this type of illiteracy describes sectors of the population that are literate in their mother tongue but unable to read or write in the language of the host country. For this reason, these people cannot be evaluated with instruments in that country's language. In the USA, 2% of the adult population, some 4 million people, are affected by these language barriers.44 On the other hand, we should not forget that rates of CI and DEM will increase the most in developing countries, where illiteracy rates are higher.45 As a result, we need instruments that do not require patients to be able to read or write and eschew all paper and pencil tasks. Tests should also be easy to administer to illiterate subjects. The aim of all of the above is to obtain assessments of entire populations by means of the same user-friendly instruments.

Psychometric problemsResults from the only meta-analysis available on the diagnostic accuracy of the MMSE in DEM screening,46 which includes 34 quality studies, show a low diagnostic accuracy for DEM. These results were found in both specialist hospital settings (memory clinics) where prevalence is high (SE: 79.8%; SP: 81.3%), and non-clinical community settings (SE: 85.1%; SP: 85.5%) or primary care settings (SE: 78.4%; SP: 87.8%) in which prevalence is low. The number of studies analysing diagnostic accuracy in CI is limited and most have been conducted in specialist hospital settings. Results from 5 studies included in that meta-analysis46 show that its diagnostic accuracy is very limited (SE: 62.7%; SP: 63.3%). In Spain, 4 studies that analyse diagnostic accuracy of MMSE in CI have recently been conducted. Results have exceeded the discrete level in both primary care settings47,48 and in specialist hospital settings.49,50

One additional problem is the significant educational bias of this instrument, which delivers scores that are strongly associated with educational level. Subjects with higher educational levels systematically obtain higher scores than those with lower levels. This effect explains the MMSE's low sensitivity in subjects with a high educational level and in subjects with DEM with normal to high scores.51 MMSE also has poor specificity in subjects with low educational levels. Thus, in a study conducted in Rochester52 among subjects with 16 or more years of education, and using the recommended cut-off point (23/24), SE was only 66% for DEM and 45% for CI. In contrast, a study performed in a Spanish rural area53 with the same cut-off point found that SP was 0% for DEM among illiterate subjects.

Some authors have suggested mitigating this problem by adjusting or correcting scores.16 This proposal, aside from being ineffective,48,54 has been criticised by other authors from a logical point of view, and not without reason. Critics argue that adjusting variables with a causal link to DEM, such as educational level, will significantly decrease validity by eliminating the validity effect55 and leading to information loss.56 Other authors propose using different cut-off points for different educational levels.53,56 Finally, others consider that no modifications can improve the global diagnostic accuracy of raw, unadjusted MMSE scores48,54 and that the true problem resides in the instrument itself. Increasing numbers of authors believe that MMSE is not an adequate instrument for use in settings with low educational levels, especially when screening for mild CI or DEM.47,48,54,57–59

Other disadvantagesOriginally, the MMSE could be used free of charge, and according to its author, this could be one of the main reasons for its popularity: “One possible reason for its popularity is that it is free”.14 The authors of the MMSE did not contemplate changing that situation (“When discussing the possibility of copyright, McHugh said, ‘That would be like copyrighting the Babinski sign”’14). However, Psychological Assessment Resources® purchased the MMSE international copyright in 2001. Since then, the company has administered the rights and delegates them, for example, to TEA Ediciones SA for Spain and Latin America. From that date on, using the MMSE requires either authorisation or payment (approximately 1 euro/test), meaning that its use is either costly or fraudulent.

These circumstances have given rise to a multitude of legitimate complaints, mainly in places in which defence of and respect for copyrights is an established social value.13,33,60,61 On the other hand, this social value has barely had an impact on other countries, including Spain, and consequently, there have been no modifications to how the instrument is used. This situation will surely evolve in the future.

Lastly, we should also highlight the implications derived from using the MMSE score as a criterion for participating in clinical trials or receiving healthcare or social benefits. Such restrictions limit access to clinical trials for subjects with lower educational levels since they systematically obtain lower scores, and access for illiterate subjects becomes impossible. This situation would become even worse if differential access arising from the MMSE educational bias were to limit access to treatment and healthcare benefits, as this runs counter to the ideals of equality defended by more advanced healthcare systems.

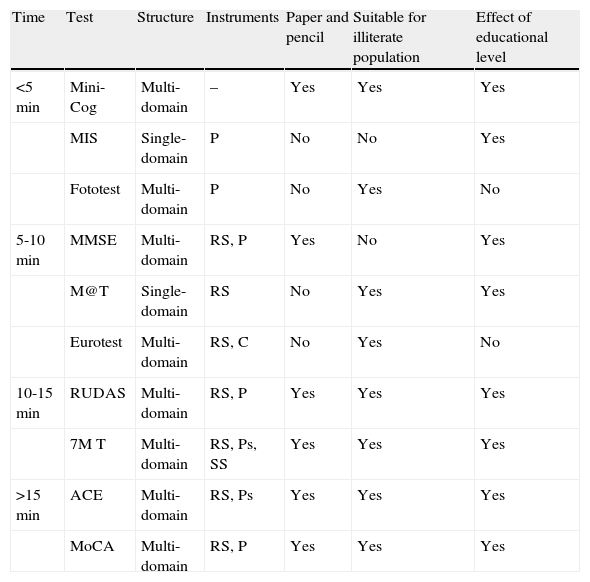

New short cognitive testsHundreds of instruments have been developed during the last few years with the aim of meeting the requirements of the ideal SCT and improving on the results of the MMSE, the current instrument of reference. Table 2 summarises the characteristics of some of these instruments. Providing detailed descriptions of these instruments falls outside of the scope of our study, but excellent reviews are available that list their characteristics and qualities and cite available evidence supporting their use.5,10,38,62–67 In general, 2 different lines of development can be observed. The first is directed towards obtaining a more valid instrument with a better diagnostic performance; the second is directed at creating easier and faster instruments.

Characteristics of new short cognitive tests.

| Time | Test | Structure | Instruments | Paper and pencil | Suitable for illiterate population | Effect of educational level |

| <5min | Mini-Cog | Multi-domain | – | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| MIS | Single-domain | P | No | No | Yes | |

| Fototest | Multi-domain | P | No | Yes | No | |

| 5-10min | MMSE | Multi-domain | RS, P | Yes | No | Yes |

| M@T | Single-domain | RS | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Eurotest | Multi-domain | RS, C | No | Yes | No | |

| 10-15min | RUDAS | Multi-domain | RS, P | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 7M T | Multi-domain | RS, Ps, SS | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| >15min | ACE | Multi-domain | RS, Ps | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| MoCA | Multi-domain | RS, P | Yes | Yes | Yes |

ACE: Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination; RS: record sheet; Instr: instruments, materials needed for testing; P: picture; Ps: different pictures; MIS: Memory Impairment Screen. MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; MoCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment; C: coins; SS: score sheet; M@T: memory alteration test; 7MT: 7 Minute Screen.

Instruments in the first group are developed for use in specialist hospital settings. They require more time to administer and they are generally longer and more complex than the MMSE. These tests facilitate diagnosis of CI and entities in which executive dysfunction and frontotemporal and frontal-subcortical profiles predominate. The most widely distributed tests of this type are the 7 Minute Screen,68 Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination,69 and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment.70 All are multi-domain instruments that require more than 10minutes to complete and include paper and pencil tasks. All show an educational bias. Each of the above instruments shows a higher diagnostic accuracy than the MMSE, especially in screening for CI or types of DEM other than Alzheimer disease.71,72

Mini-Cog73 and Fototest74 are two well-known examples of the second line of development that creates simple and short instruments for use in primary care settings and situations with strict time limits. Mini-Cog uses a 3-item recall test for memory and a simplified version of the clock-drawing test. Although it only requires 2 to 3minutes, some studies show that its diagnostic utility is similar to that of MMSE.75 However, a study performed in Spain did not show good results for CI screening in primary care settings,76 probably due to the instrument being inadequate for subjects with low educational levels.77 Fototest is a very short multi-domain instrument (<3min) that is suitable for illiterate subjects and does not show an educational bias. It is more cost-effective and efficient than MMSE as a means of screening for DEM and CI in primary care settings.54 It performs similarly to other instruments with longer administration times that are also suitable for illiterate subjects.78

Instruments adapted for specific conditions have also been designed. Examples include the M@T79 and the MIS,80 tests that are especially useful for detecting amnestic mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease since they assess memory exclusively. Other instruments such as Eurotest81 or RUDAS,82 have been specifically designed for testing illiterate subjects in multi-cultural environments.

ConclusionsSCTs, indispensable and essential tools in clinical practice, must fulfil minimum psychometric and applicability requirements. MMSE, currently the most widely used SCT, presents several significant limitations. It cannot be used with illiterate subjects, scores are heavily influenced by educational level, its utility for CI screening is reduced, and it is not freely available.

At present, some instruments are available free of charge that lack these limitations and have demonstrated higher diagnostic accuracy and even better efficiency than the MMSE in direct comparison.54

The history of medicine is full of examples of excellent diagnostic tools that have been naturally replaced by newly developed ones providing better results. For example, the rigid stethoscope was replaced by the flexible phonendoscope, and the mercury thermometer fell out of use with the arrival of the digital thermometer. Therefore, it may now be time to acknowledge the MMSE's important place in the history of medicine and grant it a well-deserved retirement. This will pave the way for shorter, more user-friendly, inexpensive instruments that are more efficient and equitable and can be freely administered to all patients.

Conflict of interestC. Carnero-Pardo is the author of Fototest and Eurotest.

We would like to thank J. Maestre Moreno and J. Olazarán Rodríguez for reviewing a draft of the article and providing useful comments and suggestions.

Please cite this article as: Carnero-Pardo C. ¿Es hora de jubilar al Mini-Mental?. Neurología. 2014;29:473‐481.