Subarachnoid haemorrhage can cause a chronic leptomeningeal inflammatory response, manifesting with alterations in the anatomical architecture of the arachnoid membrane, known as arachnoiditis.1 These changes can range from mild thickening to severe adhesions in the subarachnoid space, including the formation of cysts that can cause spinal cord compression1; while these are rare, they usually follow certain patterns of regional localisation and time of onset. The case described in this article presents several differences from the other cases reported to date.

Clinical caseThe patient is a 52-year-old man with history of subarachnoid haemorrhage secondary to rupture of an aneurysm in the left posterior inferior cerebellar artery, treated with embolisation, and ventricular-peritoneal CSF shunt due to hydrocephalus; the valve was replaced on 3 occasions due to obstruction caused by blood remnants in the system.

Eight years later, he developed progressive spastic tetraplegia secondary to extrinsic spinal cord compression, which MRI revealed to be due to arachnoid cysts between C2 and C6, predominantly anterior to the spinal cord; these findings were associated with thinning of the spinal cord and caused syringomyelia between T4 and the conus medullaris.

The patient underwent surgery with posterior C2-C4 laminoplasty and removal of all the cysts identified in this region. The patient’s gait temporarily improved after the procedure, but deteriorated again at 6 months despite rehabilitation treatment; he also developed proximal weakness in the upper limbs. We opted to perform a second surgical intervention, performing arachnoidolysis. Progression after this procedure was unfavourable, with reappearance of the arachnoid cysts in follow-up radiology studies and progressive loss of strength; the patient has only recovered partial motor function in the left arm.

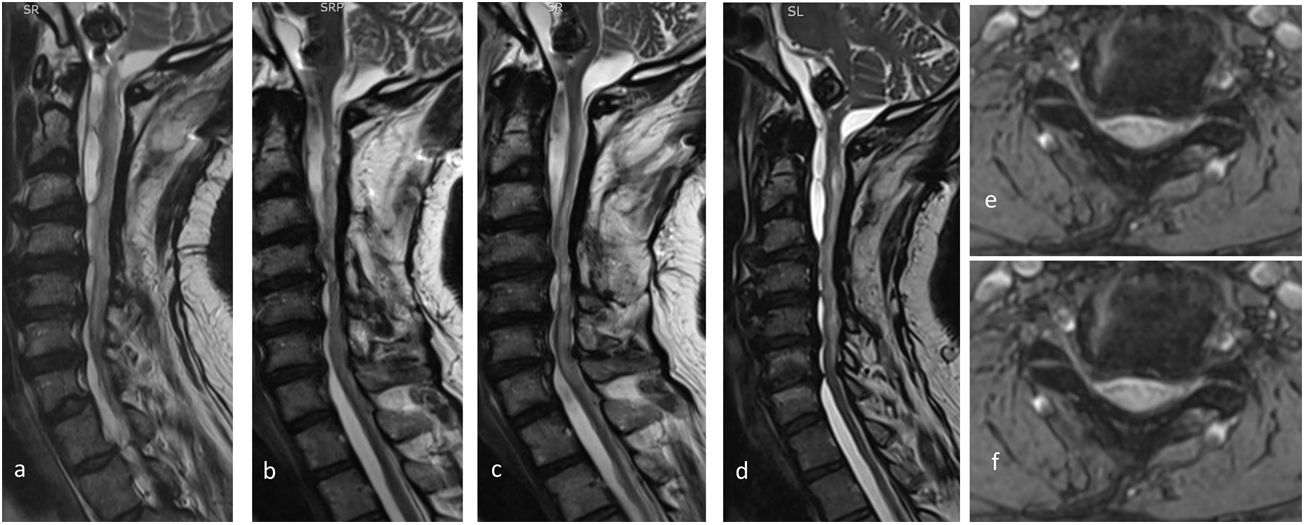

Fig. 1 shows the patient’s radiological progression.

The MRI study showed cervical spondylotic myelopathy with disc degeneration in at least 5 intervertebral spaces, with hypertrophy and calcification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. These lesions caused stenosis of the cervical spinal canal. T2-weighted axial and sagittal sequences show the progression of the multiple arachnoid cysts and trabeculae from the craniocervical junction to the C7 level, with severe compression and atrophy of the spinal cord. Postoperative images obtained in a) 2014, b) 2015, c) 2016, d) 2018, e) 2014, and f) 2018. Gutiérrez et al.

Intraspinal arachnoid cysts are a rare entity and remain undiagnosed in many cases.2,3 They generally affect the thoracic spine,3–5 with only 15% of cases affecting cervical segments.6–8 The posterior intradural segment is clearly the most frequently affected, to the extent that anterior localisation has been described as exceptional.5,9 Such specific localisation is probably related to long periods of rest in the supine position, which would favour blood stagnation in patients with thoracic kyphosis.10

These formations may be congenital, acquired, or idiopathic.11 It has been suggested that the main aetiological mechanisms are such inflammatory processes as meningoencephalitis and post-haemorrhagic inflammation,11 including cases of spontaneous haemorrhage of vascular (rupture of cavernomas and dural fistulae), post-traumatic, and postoperative origin.2

Although its aetiopathogenesis is not well understood, arachnoiditis is generally believed to cause fibrosis and thickening of the leptomeninges and local membrane adhesions, leading to mechanical and secretion mechanisms that contribute to the maintenance and growth of the cystic cavities3,4,12; when they reach a determined size, the compressive effect causes neurological symptoms.

The disease is diagnosed by spinal cord MRI. Differential diagnosis includes neurocysticercosis, neurenteric cysts, and epidural abscesses.11

In most case reports, as in our own, the treatment of choice is laminectomy and resection of the cysts.6 Multiple resources are available for treating the cysts, including puncture and fenestration,3 marsupialisation, atrial or peritoneal shunt, and a watchful waiting approach with clinical and radiological follow-up.

Prognosis is influenced by the degree of neurological involvement prior to surgery, progression time, cyst size,13 and how early the procedure is performed. We must not rule out conservative treatment in these cases,14 although the watchful waiting strategy is difficult to sustain in the long term,15 particularly in cases of progressive impairment.

ConclusionPost-haemorrhagic arachnoid cysts, like cysts of infectious origin, are a very rare complication; therefore, they should be suspected in patients presenting delayed neurological impairment after the underlying disease due to the risk of irreversible spinal cord lesions. Management almost always requires early surgical treatment, although given the low prevalence of the condition, the truly difficult decision is the moment and type of intervention.

Please cite this article as: González Alarcón JR, Gutiérrez Morales JC, Álvarez Vega MA, Antuña Ramos A. Quistes aracnoideos espinales: una manifestación tardía de la aracnoiditis poshemorrágica. Neurología. 2022;37:152–154.