SARS-CoV-2 was first described in patients with atypical pneumonia in Wuhan (China).1 Subsequent studies have addressed the complications associated with coagulation disorders, due to their frequency and severity.2 Among these disorders, haemorrhagic complications, though less frequent than thrombotic complications, are associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality and force us to assess the risk and benefits of starting or maintaining anticoagulation therapy.

We present the case of a 74-year-old woman, a former smoker, with personal history of arterial hypertension and dyslipidaemia. She had been under follow-up by the neurology department since 2019 due to stroke in the territory of the right posterior cerebral artery, which resulted in left homonymous hemianopsia; stroke aetiology was undetermined according to the aetiological study. The study incidentally detected a porencephalic cyst in the left parieto-occipital region, measuring 6.5×3.5cm.

In March 2020, the patient visited the emergency department due to respiratory symptoms; a PCR test of nasopharyngeal exudate detected SARS-CoV-2. She was initially admitted to the intensive care unit and subsequently transferred to the respiratory intermediate care unit, where she presented an episode of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation; treatment was started with low–molecular weight heparin dosed at 60mg every 12hours (patient weight: 60kg).

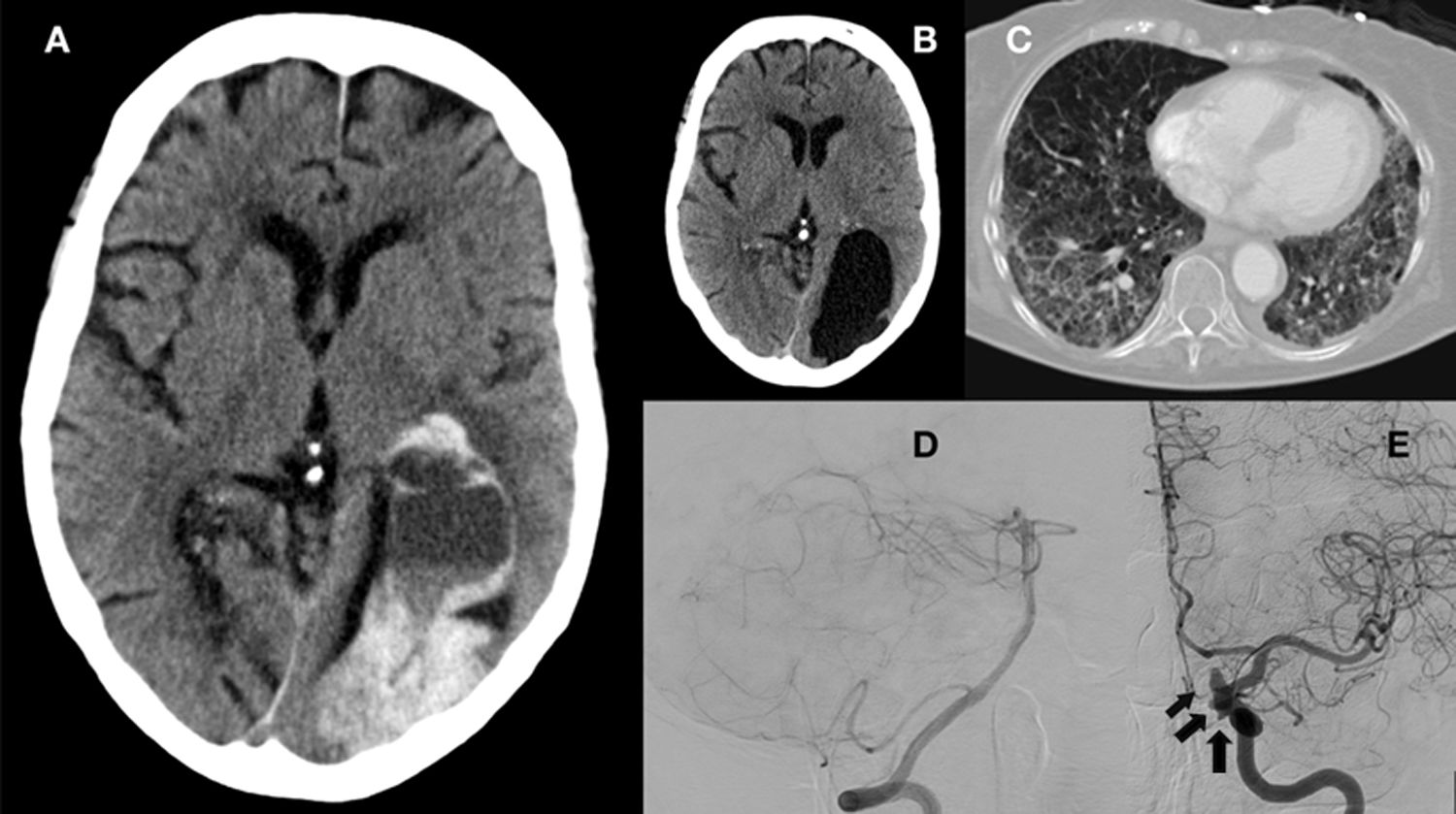

Ten days after onset of anticoagulation therapy, and 45 days after diagnosis of COVID-19, the patient presented mixed aphasia of unknown origin, with arterial blood pressure of 130/90mm Hg and preserved consciousness. Code stroke was activated. Head CT detected a haemorrhage within the cavity of the porencephalic cyst (Fig. 1). A CT angiography study of the circle of Willis showed no underlying vascular alterations, and a contrast study found no signs of active bleeding. In the preceding days, the patient had presented elevated levels of D-dimer (up to 1.54μg/mL; normal range, 0.15-0.50), fibrinogen (524mg/dL; normal range, 150-400), and LDH (308 U/L; normal range, 135-214), with a platelet count of 242 000/μL (normal range, 150 000-350 000); prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times were within the normal range.

A) Brain CT showing a porencephalic cyst in the left parieto-occipital region displaying haemorrhage (8.5×4×7cm) and causing moderate mass effect, obliterating the left temporal, parietal, and occipital sulci, and causing anterior displacement of the left lateral ventricle. Blood content was observed in the body and temporal horn of the left lateral ventricle. Gliosis and malacia in the right paramedian occipital region, associated with an old stroke in the territory of the right posterior cerebral artery. B) Brain CT scan performed 3 months before admission due to COVID-19, revealing a porencephalic cyst in the left parieto-occipital region and an area of gliosis and malacia in the right paramedian occipital lobe, with no evidence of bleeding. C) Chest CT scan performed during hospitalisation, showing multiple ground-glass opacities in both lungs, more prominent in pressure areas. D) Brain angiography (right vertebral artery injection) showing normal morphology of the basilar and posterior cerebral arteries. E) Brain angiography showing several aneurysms along the internal carotid artery (black arrow). The first aneurysm measured 3.6×3.6mm, with a neck of 2.7mm, and was located on the posterior aspect of the cavernous segment. The second measured 3.09×1.1mm, with a neck of 2.3mm, and was located on the posterolateral aspect of the clinoid segment. The third measured 2.5×5.2mm, with a neck of 3.7mm, and was located on the superior aspect of the ophthalmic segment.

In view of these findings, the patient was assessed by the neurosurgery team, who ruled out surgery, and anticoagulation therapy was suspended.

The aetiological study also included a brain angiography study, which revealed aneurysms with irregular borders in the territory of the left internal carotid artery, but no vascular anomalies of the posterior circulation that might explain the haemorrhage (Fig. 1).

Twenty-eight days after the haemorrhage, the patient was diagnosed with pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE) in the segmental arteries of the right lung. After assessing the risks and benefits of anticoagulation therapy, we opted for inferior vena cava filter placement.

At the follow-up consultation 3 months after the stroke, aphasia had resolved.

DiscussionSeveral hypotheses have attempted to explain the aetiopathogenic mechanisms of coagulation disorders in patients with COVID-19. One such hypothesis is based on the virus’ affinity for the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, associated with increased prothrombotic and proinflammatory activity of angiotensin II. Other potential mechanisms include immune system activation with macrophage activation and cytokine release, and vasculitis.3

Regarding the virus’ affinity for the ACE2 receptor, some authors suggest that ACE2 dysregulation may cause alterations in blood pressure and consequently hypertensive haemorrhages. Other authors postulate virus-induced endothelial damage,4 a prothrombotic state due to decreased levels of coagulation factors, and such concomitant factors as kidney disease or anticoagulation therapy.3 Furthermore, haemorrhagic complications may occur in the context of cerebral venous thrombosis or haemorrhagic transformation of stroke.5

Guidelines on anticoagulation therapy in patients with COVID-19 are constantly being reviewed and updated, and recommend prophylactic anticoagulation in patients with COVID-19 and no contraindications; the dose should be adjusted in patients without contraindications but presenting higher thrombotic risk.6

Few studies analyse the clinical characteristics of patients presenting brain haemorrhages in the context of COVID-19. One case series reported a mean age of 52.2 years, history of arterial hypertension, lobar localisation affecting the anterior circulation, and a mean of 32 days from symptom onset to haemorrhage.7 Our patient, in contrast, was considerably older; symptoms appeared 45 days after diagnosis of COVID-19 and the location of the haemorrhage was atypical (within a porencephalic cyst).

The unusual location of the haemorrhage in our patient is noteworthy. Porencephalic cysts are defined as cerebrospinal fluid accumulation in a cavity in the brain parenchyma that communicates with the ventricular system, the subarachnoid space, or both. These lesions may be congenital or acquired. In adults, they are found incidentally on brain imaging studies and are rarely associated with complications; when complications do present, they are typically epileptic seizures, focal neurological signs, and low intelligence quotient.8

The literature includes reports of intracystic and subdural haemorrhage in arachnoid cysts. These cysts, unlike porencephalic cysts, are located between the brain surface and the skull, within the arachnoid membrane, and do not communicate with the ventricular system. The most widely accepted aetiopathogenic hypothesis for intracystic haemorrhage is traumatic injury to the walls of vessels surrounding the cyst.9 Cases have also been reported of intracystic haemorrhage secondary to aneurysm rupture; this is rare, however. In these cases, it has been suggested that haemorrhage may be explained by the proximity between the vessel wall and the cyst wall, combined with arterial pulsatility.10

To our knowledge, however, no cases have been reported of intracystic haemorrhage in patients with porencephalic cysts.

The aetiological study failed to determine the cause of the haemorrhage in our patient, and we were unable to rule out an association with coagulation disorders secondary to COVID-19 or anticoagulation therapy. In view of the location of aneurysms in the carotid artery territory, which were not contiguous with the cyst, and in the absence of haemorrhage at other locations, we may rule out aneurysm rupture as the cause of intracystic bleeding.

The patient also presented thromboembolic complications after anticoagulant discontinuation, which underscores the complexity of managing anticoagulation therapy in patients with COVID-19.

ConclusionsCerebral haemorrhage is a rare complication of COVID-19 but may be associated with poor outcomes, further complicating the challenge of anticoagulation therapy in patients with severe infection. This case demonstrates that cerebral haemorrhage may occur at such atypical locations as within the cavity of porencephalic cysts.

FundingThis study received no funding of any kind.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Muro I, Ramos C, Barbosa A, Vivancos J. Hemorragia en el interior de la cavidad de un quiste porencefálico: una complicación hemorrágica en paciente con COVID-19. Neurología. 2022;37:504–507.