AIDS-related disorders of the nervous system are common and may be caused directly by the HIV virus, by cancers or opportunistic infections (diseases caused by bacteria, fungi, protozoa and other viruses that would not otherwise affect people with healthy immune systems) or by the toxic effects of medication.1,2

Neurological illnesses can affect either the peripheral nervous system or the spinal cord, brain or meninges in the central nervous system. Intracranial lesions can be categorized as diffuse (meningitis or encephalitis) or focal, and onset may be acute, subacute or chronic.

In our environment, the two most common forms of subacute and chronic meningoencephalitis are tuberculous and cryptococcal meningitis.3,4 More specifically, the diagnosis of tuberculous meningoencephalitis (TBM) is challenging since microbiological studies are frequently negative and presumptive treatment is required with evaluation of treatment response.3 It is interesting therefore to report a case in which the final diagnosis was neurolymphomatosis, a disease that is only exceptionally reported in HIV-infected patients.

The patient was a 39-year-old woman, with a personal history of inhaled drug use (cocaine). She was diagnosed with HIV infection (CD4: 150 cells/μL and viral load 20,000 copies/μL) in October 2018 and started treatment with abacavir, lamivudine and dolutegravir, accompanied by left peripheral facial nerve palsy with skin lesions suggestive of varicella zoster virus (VZV) infection, treated with valacyclovir. Despite resolution of the VZV lesions, the patient continued to have cervicalgia, paresthesia and weakness in the lower limbs. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) was performed, which revealed no pathological findings, and a lumbar puncture (November 2018), which yielded clear cerebrospinal fluid with mononuclear pleocytosis (leukocytes: 180/μL, mononuclear cells: 85%), hypoglycorrhachia (CSF glucose: 15 mg/dL), hyper-proteinorrhachia (proteins: 597.7 mg/dL) and elevated ADA (12 U/L). All the microbiological studies (standard bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi and viruses) were negative. Upon suspicion of tuberculous meningitis, treatment was started with rifampicin, isioniazid and pyrazinamide.

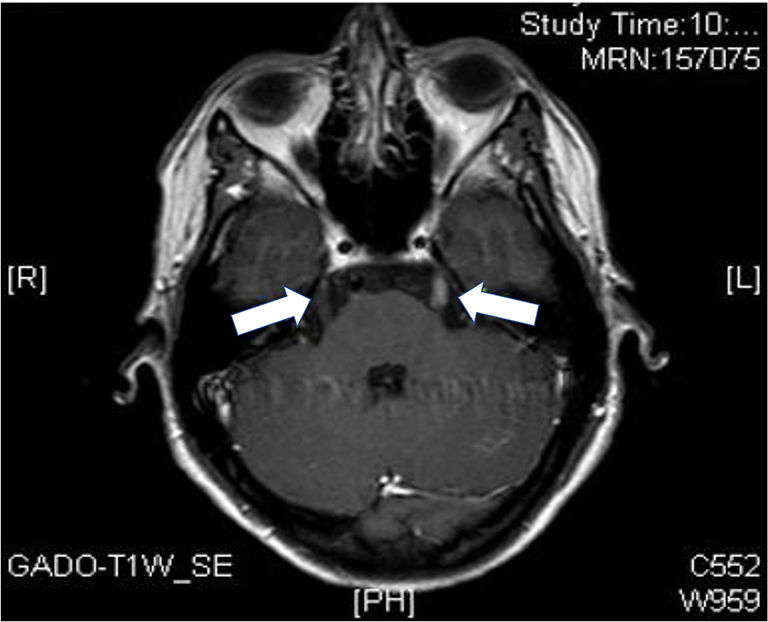

In February 2019, the same set of symptoms persisted and was associated with intolerance to oral administration, so that another lumbar puncture was performed, with similar CSF characteristics to the previous one, and another NMR imaging test, which showed bilateral enhancement of the cranial nerves V (left and lower right), without brain parenchyma involvement (Fig. 1). Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) was considered as a diagnostic possibility (after the CD4 count increased from 150 to 394 cells/μL), so that treatment with corticosteroids was started.

Four months after starting anti-TB treatment and a month of corticosteroid therapy, complete paralysis of the third cranial nerve on the right side and claudication of the upper left limb in the Barré maneuver were observed, with 3/5 proximal muscle strength in that limb, hyperreflexia in the upper limbs bilaterally with left Hoffman signs. Another brain MRI test was performed, in which white matter hyperintensities adjacent to the third ventricle, restricted diffusion sequences and enhancement following contrast agent administration were visualized, as well as scattered millimetric foci in the white matter with gadolinium enhancement. Cervical MRI showed diffuse posterior spinal cord involvement at C5, C6–C7, D3 and D5, without enhancement after contrast. A new CSF sample revealed: 180 leukocytes (85% mononuclear; 15% polymer-phonuclear), glucose: 15 mg/dL, proteins: 600 mg/dL and negative microbiological studies. By CSF cytology and flow cytometry, malignant cells diagnosed as diffuse large B cell type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (DLBCL-NHL) were detected.

In April 2019, chemotherapy was started with methotrexate, cytarabine (AraC) and rituximab. In the whole-body CT scan for staging lymphoma, two left-sided para-aortic lymph nodes were visualized, and mild B-lymphocyte infiltration in bone marrow biopsy (DLBCL-NHL vs Burkitt lymphoma). After two months of treatment, the control MRI showed improvement and even resolution of the lesions adjacent to the aqueduct of Sylvius, bilateral thalamic lesions and in the corpus callosum. The CSF study was normal at that time.

After being discharged in July 2019, the patient was readmitted 10 days later with generalized bone pain, weakness and holocranial headache. A new bone marrow biopsy showed progression of the neoplasm, with 65% BM infiltration by cells compatible with DLBCL-NHL by cytology and flow cytometry immunophenotyping. Karyotyping and FISH testing on BM biopsy specimens showed two cell lines, with separation of the c-MYC gene (locus 8q24) in the second one, thus establishing a diagnosis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma with features intermediate between Burkitt lymphoma and DLBCL-NHL. Cyclophosphamide was added to the treatment.

Despite treatment, the patient experienced disease progression and it was eventually decided to manage the symptoms and transfer her to the palliative care unit, where she died shortly afterwards.

In the case presented here, the initial diagnosis was tuberculous meningitis, based on the subacute clinical course with mononuclear pleocytosis, hypoglycorrhachia, hyperproteinorrhachia and a negative microbiology. Elevated ADA levels supported the diagnostic suspicion, since according to various studies, a CSF ADA cut-off level of 10 U/L has between 60 and 100% sensitivity for tuberculous meningitis.5 Nevertheless, an elevated CSF ADA level is of limited specificity, since it has also been reported in patients with other infections (namely cryptococcosis, toxoplasmosis, neurosyphilis, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), inflammatory syndrome (i.e. IRIS) and neoplasms (lymphomas).6,7 Limited specificity is due to the fact that the ADA enzyme intervenes in the purine metabolism and is a marker of mononuclear cells (ADA 1, widely distributed, and ADA2, limited to monocytes and macrophages).8

After initiating tuberculosis treatment, the neurological lesions continued to progress and other possibilities were considered, such as PML or IRIS. Corticosteroids were added to the treatment, without an adequate response. An important part of the patient's evolution was the involvement of various cranial nerves, demonstrated both by the physical exploration (CN III) and in imaging studies (enlargement of CN V bilaterally). Nerve enhancement after the administration of gadolinium is associated with disruption of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), although it does not have a pathogenic orientation to the causative disease.9

The final diagnosis was neurolymphomatosis, a rare entity characterized by infiltration of cranial nerves, peripheral nerves, nerve roots or plexuses by malignant lymphocytes.10,11 This is a rare neurological manifestation found in non-Hodgkin lymphomas, fundamentally DLBCL and leukemias; it is usual for hematologic malignancy to be diagnosed prior to neurolymphomatosis.12 However, despite the fact that primary lymphoma is frequently the cause of focal central nervous system involvement in HIV-infected patients,13 neurolymphomatosis is rare. Indeed, after reviewing the literature, we found only one reference to it, which had a completely different evolution, with a diagnosis of systemic lymphoma prior to neurolymphomatosis.14

In summary, neurolymphomatosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients with HIV infection and a biological clinical picture of subacute meningoencephalitis with lymphocytic pleocytosis, hypoglycorrhachia and hyper-proteinorrhachia and elevated CSF ADA levels. Cranial nerve enhancement on MRI (mainly CN II, III, V, VI and VII) is also common, but not specific.9 In neurolymphomatosis, differential data reported include restricted diffusion on some sequences9 or decreased enhancement after steroid therapy,15 although the sensitivity and specificity of these have not been evaluated. It is possible that earlier diagnosis and treatment in the case presented would have been associated with a better prognosis.

FundingNone to declare.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical considerationsThe informed consent of the patient has been obtained for this publication, and we have followed the procedures of our centre for the treatment of the patient's data.

Authors'contributionsMaterial preparation, data collection were performed by Dra. Pérez Navarro, Dra. Jaén Sanchez and Dra. Carranza-Rodríguez. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Dra. Pérez Navarro and Dr. Pérez Arellano and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Guidance and support were given throughout by Dr. Pérez-Arellano.

We would like to thanks Ms. Janet Dawson for her help in revising the English version of the manuscript.