Lung cancer remains one of the leading causes of cancer death worldwide. This study examines lung cancer mortality trends in Andalusia, Spain, from 2003 to 2022, focusing on gender differences and the influence of age, period and cohort effects.

Material and methodsThis longitudinal ecological study analyzed lung cancer mortality data in Andalusia from 2003 to 2022, using age-period-cohort (A-P-C) and joinpoint regression models. Mortality rates were calculated by sex, age group, and standardized to the 2013 European Standard Population.

ResultsBetween 2003 and 2022, Andalusia recorded 68,480 lung cancer deaths, with a significant gender disparity. Male mortality decreased (−1.9%), while female mortality increased (3.5%). Joinpoint analysis revealed a notable rise in female mortality rates after 2015. Age-specific analyses showed decreasing rates for men across all age groups, with a sharper decline for younger men. Women experienced increasing rates, particularly among those aged 35–64. The A-P-C model identified significant cohort effects, with decreasing rate ratios for men and increasing ones for women, reflecting historical smoking patterns.

ConclusionsLung cancer mortality in Andalusia has exhibited a stark gender divide, reflecting the region's historical smoking patterns. While declining rates among men and younger women indicate the efficacy of tobacco control measures, the persistent rise in female mortality underscores the enduring effects of past smoking habits. These findings emphasize the imperative for ongoing public health initiatives and gender-specific interventions to mitigate the burden of lung cancer in Andalusia.

El cáncer de pulmón sigue siendo una de las principales causas de muerte por cáncer en todo el mundo. Este estudio examina las tendencias de mortalidad por cáncer de pulmón en Andalucía, España, desde 2003 hasta 2022, centrándose en las diferencias según sexo y la influencia de los efectos de edad, período y cohorte.

Material y métodosEste estudio ecológico longitudinal analizó los datos de mortalidad por cáncer de pulmón en Andalucía de 2003 a 2022, utilizando modelos de regresión de edad-período-cohorte y joinpoint. Las tasas de mortalidad se calcularon por sexo, grupo de edad y se estandarizaron a la población estándar europea de 2013.

ResultadosEntre 2003 y 2022, Andalucía registró 68.480 muertes por cáncer de pulmón, con una disparidad según sexo significativa. La mortalidad en los hombres disminuyó (−1,9%), mientras que la mortalidad en las mujeres aumentó (3,5%). El análisis de joinpoint reveló un notable aumento en las tasas de mortalidad en las mujeres después de 2015. Los análisis por edad mostraron tasas decrecientes para los hombres en todos los grupos de edad, con un descenso más pronunciado en los hombres más jóvenes. Las mujeres experimentaron tasas crecientes, particularmente entre las de 35 a 64 años. El modelo de regresión de edad-período-cohorte identificó efectos de cohorte significativos, con tasas de disminución para los hombres y de aumento para las mujeres, reflejando patrones históricos de consumo de tabaco.

ConclusionesLa mortalidad por cáncer de pulmón en Andalucía ha mostrado una clara división según sexo, reflejando los patrones históricos de consumo de tabaco en la región. Si bien las tasas en declive entre hombres y mujeres jóvenes indican la eficacia de las medidas de control del tabaco, el aumento persistente en la mortalidad femenina subraya los efectos duraderos de los hábitos de consumo de tabaco del pasado. Estos hallazgos enfatizan la imperiosa necesidad de iniciativas de salud pública continuas y de intervenciones específicas por sexo para mitigar la carga del cáncer de pulmón en Andalucía.

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer death worldwide and continues to be a major global health problem. In 2022, it accounted for 2.5 million new cases and 1.8 million deaths, representing 12.4% of all cancers and 18.7% of cancer-related deaths.1

Spain reflects these global trends, with lung cancer rates increasing in women and decreasing in men. However, mortality trends often lag behind incidence due to the delayed effects of risk factors, particularly smoking.2 Studies at both national3–5 and regional levels6–10 consistently show these gender differences, but they often overlook the influence of birth cohort effects – key to understanding generational differences in lung cancer risk. These effects are mainly due to changes in smoking behaviour between generations.11,12

Recent research has highlighted regional disparities in lung cancer mortality trends across Spain. In wealthier regions such as Madrid, Navarre, and the Basque Country, younger cohorts – especially men – have generally shown improved outcomes, with decreasing lung cancer mortality rates likely due to a range of contributing factors. However, while these factors may contribute to regional differences, the underlying causes of these disparities are complex and not yet fully understood, warranting further investigation. Nationally, a strong cohort effect remains, especially among women born after the Spanish Civil War, whose lung cancer mortality rates have been slower to decline – likely reflecting historical smoking patterns and socioeconomic factors.6,13

In Andalusia, lung cancer mortality rates for men and women have been converging since the mid-1990s. This trend is largely driven by higher female mortality in younger cohorts born after 1940, corresponding to increased smoking rates among women in the late 20th century. This persistent cohort effect suggests that future mortality trends in Andalusia may differ from those in other regions.7,8

This study aims to deepen our understanding of lung cancer mortality trends in Andalusia using age-period-cohort (A-P-C) and joinpoint regression models. Building on previous national12 and regional research,14 our analysis explores the complex interaction between age, period and cohort effects, identifying significant changes in mortality trends and key inflexion points.

Material and methodsStudy design and data sourcesThis longitudinal ecological study, conducted according to STROBE guidelines, examines trends in lung cancer mortality in Andalusia from 2003 to 2022. Mortality data for the region, including population and lung cancer deaths, were obtained from the National Institute of Statistics. The data were stratified by sex and five-year age groups, from less than 5 years to 85 years and older. Lung cancer deaths were classified using ICD-10 codes C33 and C34.

Statistical analysisAge-standardized mortality rates (ASMRs) were calculated by sex and age group (35–64 years, over 64 years and all ages combined). Standardization was performed using the direct method with the 2013 European Standard Population, which allows valid comparisons by adjusting for differences in age distribution.

Mortality trends were analysed using the National Cancer Institute's Joinpoint Regression Program (version 5.2.0.0). This programme identifies significant inflexion points (joinpoints) in the data and calculates the annual percentage change (APC) for each segment and the average annual percentage change (AAPC) for the entire study period. The pairwise comparison function was used to compare trends between males and females. Statistically significant trends (p<0.05) were classified as ‘increasing’ or ‘decreasing’, while non-significant trends were classified as ‘stable’. All rates are presented per 100,000 persons, and ratios between males and females have been calculated.

To examine the factors influencing these trends, an age-period-cohort (A-P-C) model was used. This model separates the effects of age, calendar period and birth cohort on lung cancer mortality. Those younger than 35 years and those older than 84 years were excluded to avoid rate instability. Data were divided into four 5-year periods (2003–2007 to 2018–2022), ten 5-year age groups (35–39 to 80–84 years) and thirteen birth cohorts (1923–1983). Age-specific mortality matrices were constructed using the National Cancer Institute's A-P-C software package. The model estimated key parameters, including age-specific rates and rate ratios (RR) for period and cohort effects relative to reference categories. Statistical significance was assessed using the Wald chi-square test (α=0.05).

Ethical considerationsThis study used anonymised data from the National Institute of Statistics and adhered to good clinical practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. As no personal or identifiable data were used, patient consent and ethics committee approval were not required.

ResultsBetween 2003 and 2022, 68,480 lung cancer deaths were recorded in Andalusia, of which 84.7% were among men (57,998) and 15.3% among women (10,482). Male mortality remained stable, with annual deaths ranging from 2813 to 2986, while female mortality almost tripled, from 284 to 828 deaths per year, especially after 2015.

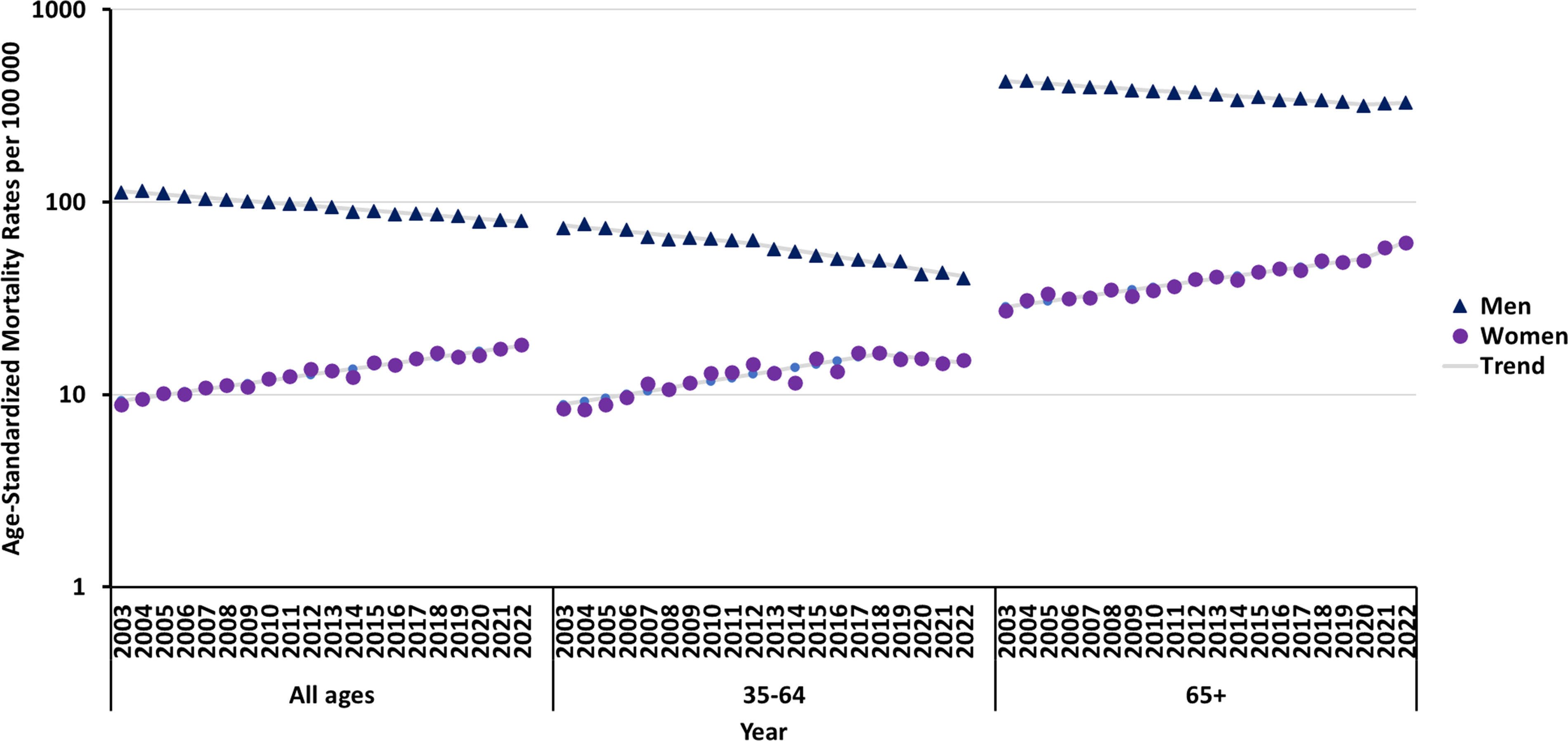

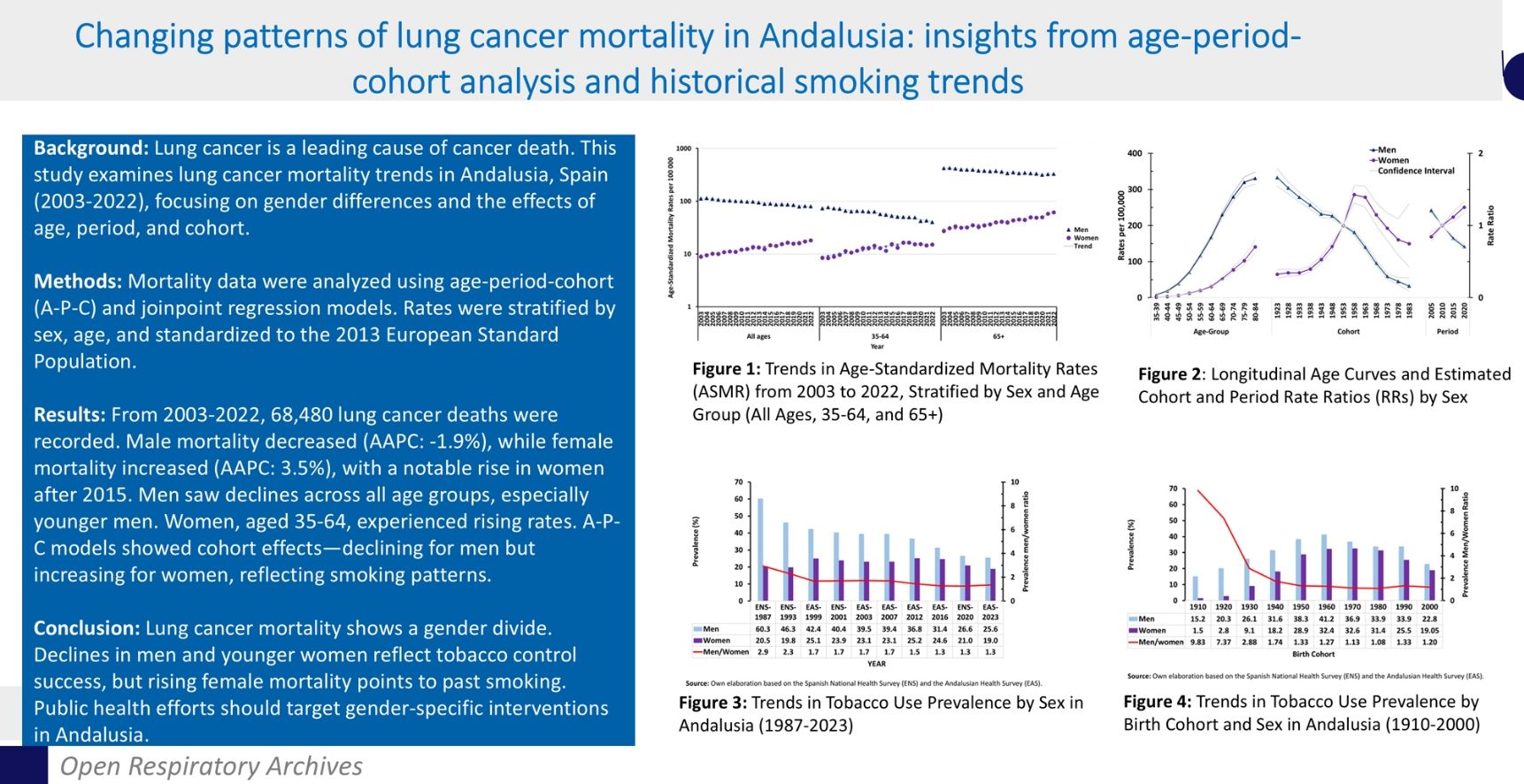

Fig. 1 shows the trends in ASMRs from 2003 to 2022, stratified by sex and age group. For men, the ASMR decreased from 112.8 to 80.4 per 100,000 (AAPC: −1.9%), while for women, the ASMR increased from 8.9 to 18.2 per 100,000 (AAPC: 3.5%). The joinpoint analysis did not reveal any significant turning points in these overall trends.

Among those aged 65 and over, ASMRs decreased for men (AAPC: −1.4%) but increased for women (AAPC: 4.2%). Joinpoint analysis showed a shift in trends for both sexes: rates for men decreased from 2003 to 2020 and then stabilized, while rates for women increased sharply until 2020 and then accelerated significantly. Among those aged 35–64, ASMRs decreased for men (AAPC: −3.2%) and increased for women (AAPC: 2.7%). Joinpoint analysis showed a more pronounced decline in rates for men after 2012 (−3.9% per year) compared with earlier years (−2.4% per year). For women, rates increased strongly until 2018 (4.1% per year), but then stabilized, with a non-significant decrease of −2.7% per year from 2018 onwards.

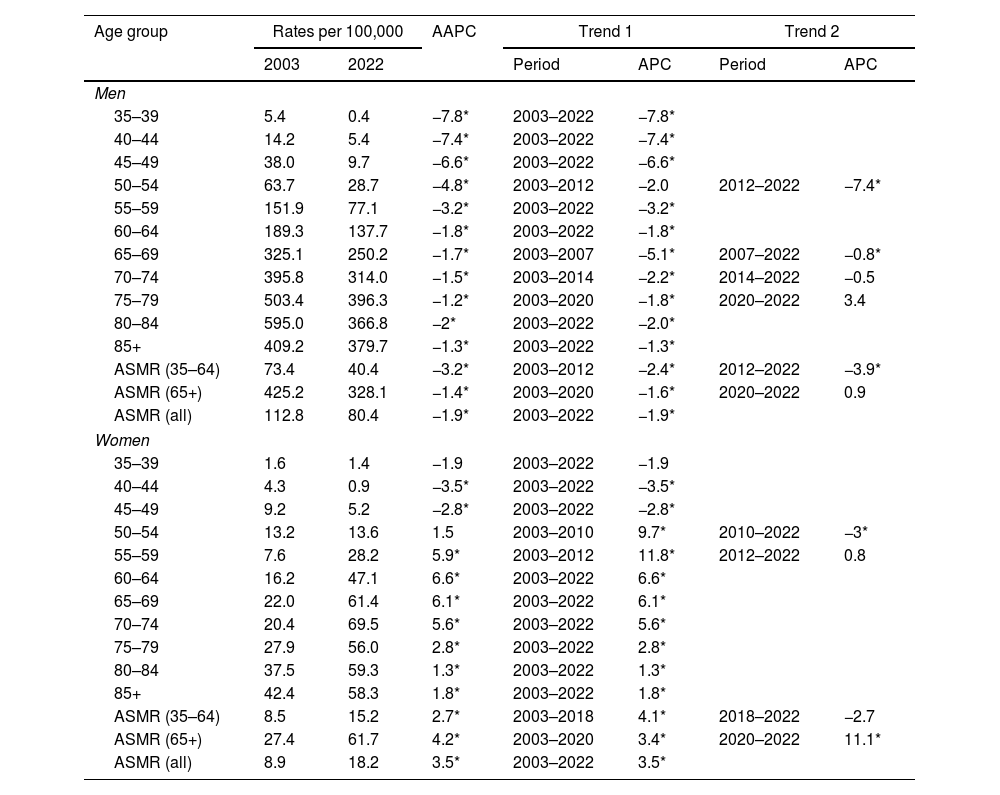

Table 1 presents the age-specific lung cancer mortality rates (ASMRs) in Andalusia from 2003 to 2022, along with the results of the joinpoint analysis, segmented by age group (all ages, 35–64 years, and 65+ years) and sex.

Age-specific and age-standardized overall and truncated (35–64 and 65+ years) mortality rates and joinpoint analysis results. Lung cancer mortality in Andalusia 2003–2022.

| Age group | Rates per 100,000 | AAPC | Trend 1 | Trend 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 2022 | Period | APC | Period | APC | ||

| Men | |||||||

| 35–39 | 5.4 | 0.4 | −7.8* | 2003–2022 | −7.8* | ||

| 40–44 | 14.2 | 5.4 | −7.4* | 2003–2022 | −7.4* | ||

| 45–49 | 38.0 | 9.7 | −6.6* | 2003–2022 | −6.6* | ||

| 50–54 | 63.7 | 28.7 | −4.8* | 2003–2012 | −2.0 | 2012–2022 | −7.4* |

| 55–59 | 151.9 | 77.1 | −3.2* | 2003–2022 | −3.2* | ||

| 60–64 | 189.3 | 137.7 | −1.8* | 2003–2022 | −1.8* | ||

| 65–69 | 325.1 | 250.2 | −1.7* | 2003–2007 | −5.1* | 2007–2022 | −0.8* |

| 70–74 | 395.8 | 314.0 | −1.5* | 2003–2014 | −2.2* | 2014–2022 | −0.5 |

| 75–79 | 503.4 | 396.3 | −1.2* | 2003–2020 | −1.8* | 2020–2022 | 3.4 |

| 80–84 | 595.0 | 366.8 | −2* | 2003–2022 | −2.0* | ||

| 85+ | 409.2 | 379.7 | −1.3* | 2003–2022 | −1.3* | ||

| ASMR (35–64) | 73.4 | 40.4 | −3.2* | 2003–2012 | −2.4* | 2012–2022 | −3.9* |

| ASMR (65+) | 425.2 | 328.1 | −1.4* | 2003–2020 | −1.6* | 2020–2022 | 0.9 |

| ASMR (all) | 112.8 | 80.4 | −1.9* | 2003–2022 | −1.9* | ||

| Women | |||||||

| 35–39 | 1.6 | 1.4 | −1.9 | 2003–2022 | −1.9 | ||

| 40–44 | 4.3 | 0.9 | −3.5* | 2003–2022 | −3.5* | ||

| 45–49 | 9.2 | 5.2 | −2.8* | 2003–2022 | −2.8* | ||

| 50–54 | 13.2 | 13.6 | 1.5 | 2003–2010 | 9.7* | 2010–2022 | −3* |

| 55–59 | 7.6 | 28.2 | 5.9* | 2003–2012 | 11.8* | 2012–2022 | 0.8 |

| 60–64 | 16.2 | 47.1 | 6.6* | 2003–2022 | 6.6* | ||

| 65–69 | 22.0 | 61.4 | 6.1* | 2003–2022 | 6.1* | ||

| 70–74 | 20.4 | 69.5 | 5.6* | 2003–2022 | 5.6* | ||

| 75–79 | 27.9 | 56.0 | 2.8* | 2003–2022 | 2.8* | ||

| 80–84 | 37.5 | 59.3 | 1.3* | 2003–2022 | 1.3* | ||

| 85+ | 42.4 | 58.3 | 1.8* | 2003–2022 | 1.8* | ||

| ASMR (35–64) | 8.5 | 15.2 | 2.7* | 2003–2018 | 4.1* | 2018–2022 | −2.7 |

| ASMR (65+) | 27.4 | 61.7 | 4.2* | 2003–2020 | 3.4* | 2020–2022 | 11.1* |

| ASMR (all) | 8.9 | 18.2 | 3.5* | 2003–2022 | 3.5* | ||

ASMR: age-standardized mortality rates; AAPC: average annual percentage change; APC: annual percentage change.

For men, mortality rates declined across all age groups, with the most notable reductions occurring in those under 60. Joinpoint analysis highlights key trends. Among men aged 50–54, rates remained stable from 2003 to 2012 but then dropped sharply by 7.4% per year from 2012 to 2022. In the 65–69 age group, the rate of decline slowed to 0.8% per year after 2007, following a faster decline of 5.1% per year. For men aged 70–79, rates stabilized after an initial decline of 1.8–2.2% per year until 2014/2020.

In women, lung cancer mortality trends varied by age group. Rates were stable in the 35–39 and 50–54 age groups, while they decreased by 3.5% and 2.8% per year in women aged 40–44 and 45–49, respectively. However, mortality increased in other age groups. Joinpoint analysis revealed significant patterns: rates for women aged 50–59 initially rose by 9.7% to 11.8% per year but reached a turning point around 2012, where rates stabilized for the 55–59 group and began declining by 3% per year in the 50–54 group from 2010.

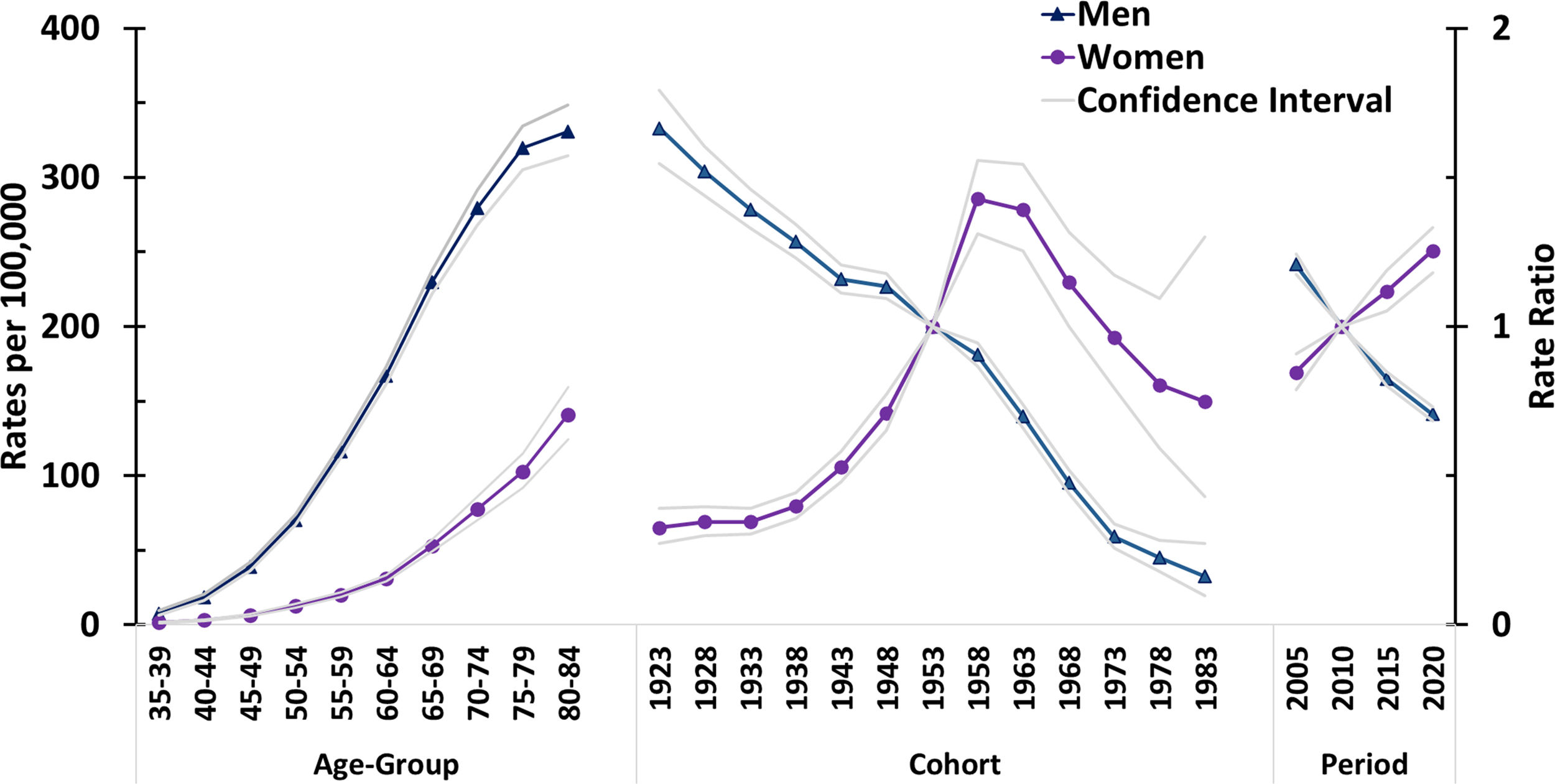

Fig. 2 shows the longitudinal age curves and the estimated cohort and period rate ratios (RRs) for both sexes. Male mortality has consistently exceeded that of females, with rates peaking in the 80–84 age group. The gender gap in age-specific mortality decreased with age, from a ratio of 6.0 in the 45–49 age group to 2.4 in the 80–84 age group.

For men, cohort RRs decreased steadily from the 1920s to the 1980s. For women, cohort RRs increased from the 1920s to the 1960s and then began to decrease. Period RRs showed a decreasing trend for men, whereas they increased for women. All cohort and period effects were statistically significant (p<0.01).

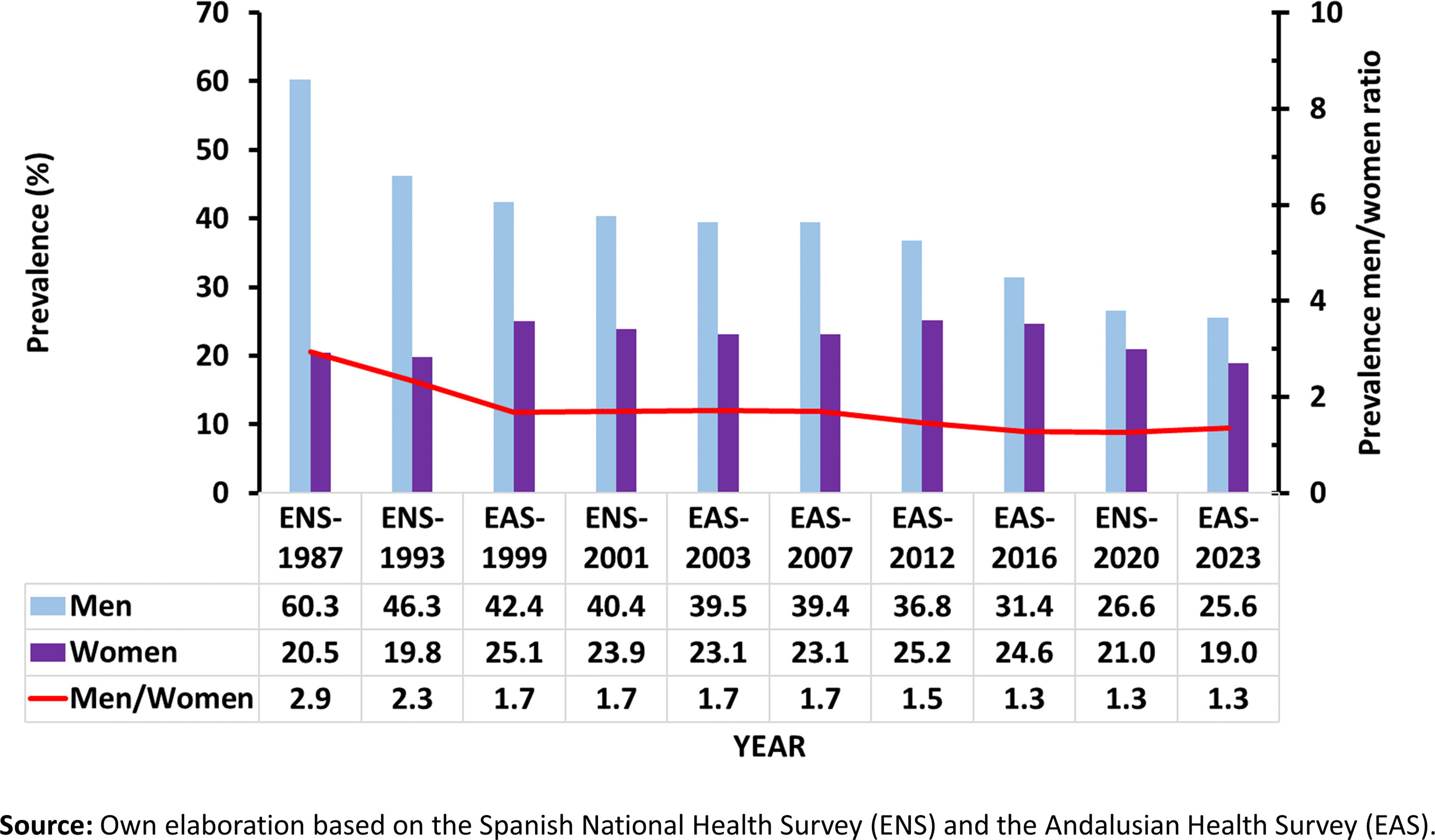

DiscussionThis study highlights the changing trends in lung cancer mortality in Andalusia, with clear gender differences driven by age, period and cohort effects. Consistent with global15,16 and national3,6,7,12–14,17 trends, lung cancer mortality has decreased in men but increased in women. These trends largely reflect historical smoking patterns (Fig. 3) and the effectiveness of tobacco control policies, highlighting the need for sustained public health efforts to reduce the burden of lung cancer.

The persistently high smoking-related mortality rates, particularly among Andalusian men,18 and the significant impact of passive smoking, which remains the highest in Spain for both sexes,19 highlight the serious health consequences of tobacco consumption. In particular, Andalusia, together with regions such as Murcia and Extremadura, has historically had some of the highest smoking rates in Spain. From 1987 to 2020, smoking prevalence among Andalusian men (Fig. 3) fell by 2.4% per year – from 60.3% to 26.6% – faster than the national average. In contrast, smoking rates among women initially increased before starting to fall in 2001, but at a slower rate (1.4% per year).20

The reduction in smoking among men has contributed significantly to the observed decline in lung cancer mortality, particularly among younger age groups. As smoking rates continue to decrease, the proportion of lung cancer cases directly linked to smoking is also expected to decline.18 However, the rising incidence of lung cancer among non-smokers – driven by factors such as second-hand smoke, air pollution, and radon exposure – represents a growing concern.21 Meanwhile, the increasing lung cancer rates in Andalusian women highlight the long-term effects of historical smoking behaviours, reinforcing the need for targeted prevention strategies.9,14

Previous studies have shown a strong correlation between smoking prevalence and lung cancer mortality, with a lag of about 15 years. This lag is influenced by factors such as the age at which smoking starts, the intensity and duration of smoking, changes in tobacco products and the implementation of control policies.22 Based on these trends, lung cancer mortality in women is expected to peak in the 2020s before starting to decline, as reflected by the decreasing risk observed in women born after the late 1950s (Fig. 2). However, stable or increasing smoking rates in older women may continue to challenge efforts to reduce mortality in this group.

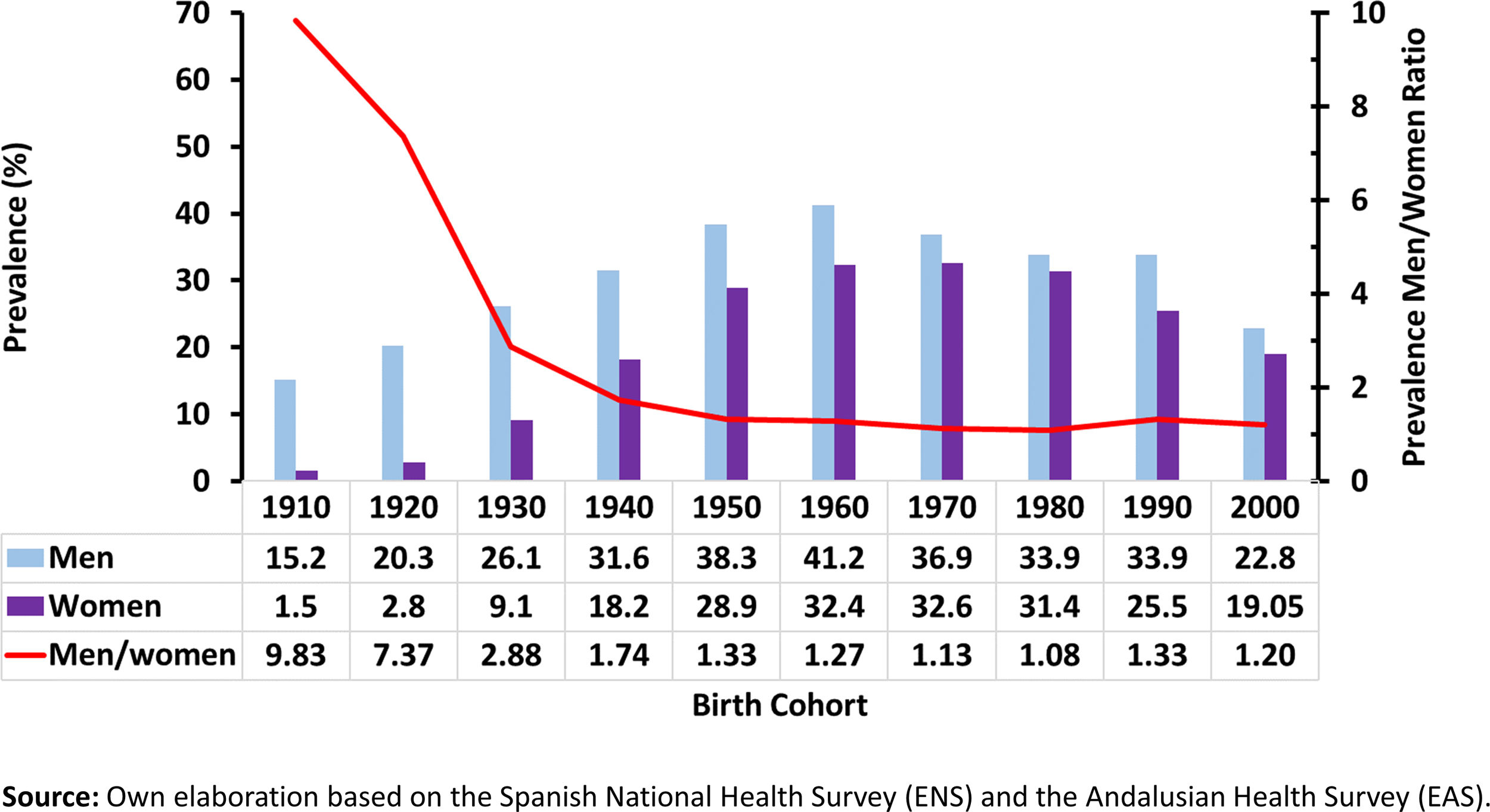

The A-P-C model revealed significant cohort effects on lung cancer mortality. For men, cohort RRs have consistently declined since the 1920s, reflecting a steady decrease in smoking prevalence among younger generations. This suggests that tobacco control policies have effectively reduced smoking rates and, in turn, lung cancer mortality in men. In contrast, cohort RRs for women increased from the 1920s to the 1960s, corresponding to the rise in smoking prevalence among women born during these decades (Fig. 4). However, the decline in cohort RRs from the 1970s onwards indicates that younger women, particularly those born from the 1980s onward, have adopted healthier behaviours. This shift is likely due to the impact of public health initiatives and evolving social attitudes towards smoking.

Smoking trends by birth cohort show distinct patterns for men and women (Fig. 4). Men born in the 1960s exhibited the highest smoking rates, but this trend reversed in later generations. Conversely, smoking prevalence among women increased steadily across cohorts, especially after the mid-20th century. Although smoking rates have begun to decline in more recent female cohorts, the overall rise in smoking among women highlights the narrowing gender gap in tobacco use. This convergence underscores the need for gender-neutral public health interventions, while still addressing historical differences in smoking patterns.

The period effects observed in this study showed a steady decline in RRs for men, while RRs for women continued to increase, reflecting the delayed impact of past smoking trends on current mortality rates.

Despite advances in diagnostic techniques and treatment modalities, such as molecular diagnostics and immunotherapies, lung cancer remains a highly lethal disease.23 While survival rates have improved for some patients, particularly those with access to personalized treatments, the overall impact on mortality has yet to be fully realized. Continued efforts in early detection, targeted therapies, and participation in clinical trials are critical to further improving outcomes.

A major limitation of this study is the reliance on mortality data due to the lack of comprehensive incidence data. Although death certificate data are generally considered reliable in Spain,4 they may be subject to inaccuracies. However, given the low survival rate for lung cancer in Spain (5-year survival rate of 12.7% for men and 17.6% for women),16 mortality data are likely to be a reasonable proxy for lung cancer incidence in this context. In addition, the use of A-P-C models, although valuable, should be interpreted with caution due to the potential variability in parameter estimates, especially for more recent cohorts with smaller sample sizes.

The study highlights the need for targeted public health interventions and continued tobacco control efforts, especially given the high smoking rates in Andalusia. Future mortality trends will be shaped not only by continued reductions in smoking but also by emerging risk factors such as air pollution, second-hand smoke, and radon exposure. Given the persistently high mortality rates among older women, tailored interventions to address smoking cessation in this demographic are essential.

While our study provides valuable insights into the trends of lung cancer mortality in Andalusia, it is important to acknowledge that the complex interplay of factors influencing these trends, including advancements in treatment modalities and access to care, necessitates further investigation. Future studies should aim to incorporate a more comprehensive analysis of these factors to better understand the underlying mechanisms driving the observed trends.

ConclusionsLung cancer mortality in Andalusia has exhibited a stark gender divide, reflecting the region's historical smoking patterns. While declining rates among men and younger women indicate the efficacy of tobacco control measures, the persistent rise in female mortality underscores the enduring effects of past smoking habits. These findings emphasize the imperative for ongoing public health initiatives and gender-specific interventions to mitigate the burden of lung cancer in Andalusia.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grants from public, commercial, or nonprofit funding agencies.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. They were involved in drafting and critically revising the manuscript for significant intellectual content. All authors approved the final version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring that any questions regarding the accuracy or integrity of any part are thoroughly investigated and resolved.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this manuscript.