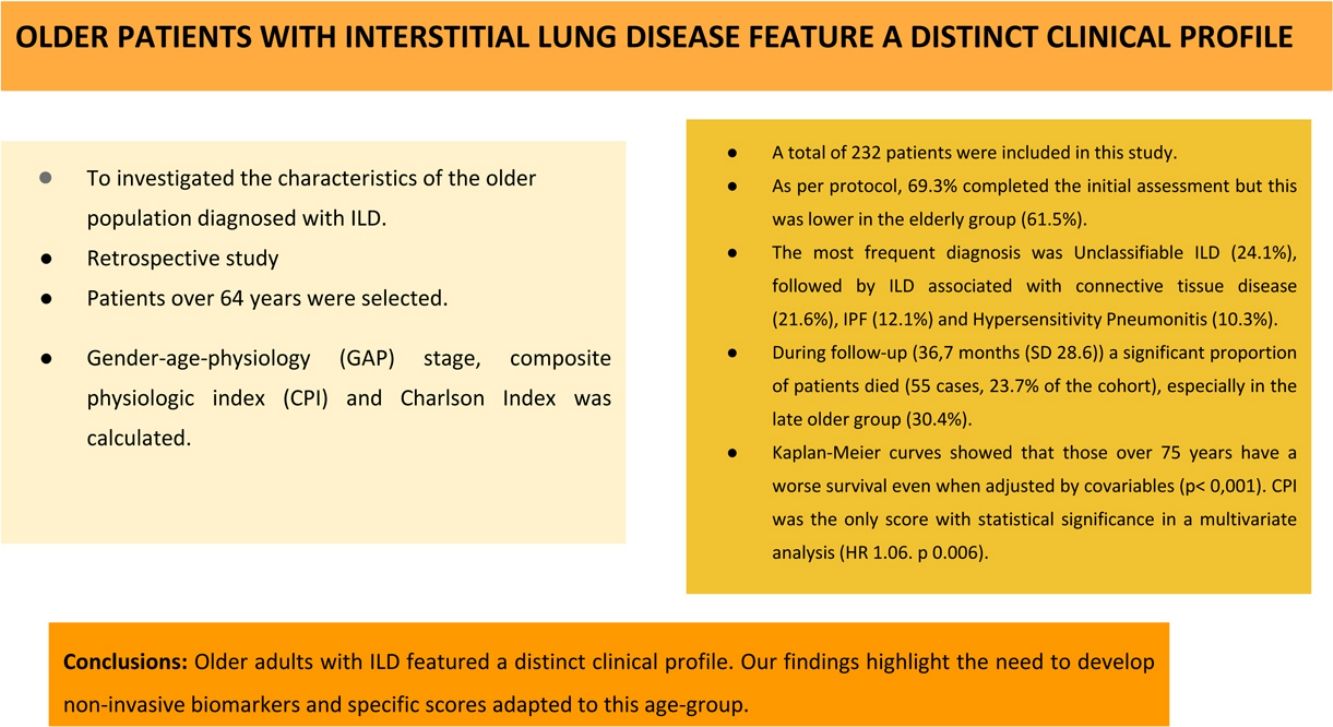

There are few studies investigating the clinical profile of older patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD), so this study investigated the characteristics of the older population diagnosed with ILD.

Material and methodsRetrospective study in a population of new referrals at an ILD clinic from January 2013 to September 2017. Patients over 64 years were selected. Data collection included diseases variables, diagnostic procedures and comorbidities. Gender-age-physiology (GAP) stage, composite physiologic index (CPI) and Charlson index was calculated. Statistical analysis was performed to investigate risk factors associated with survival.

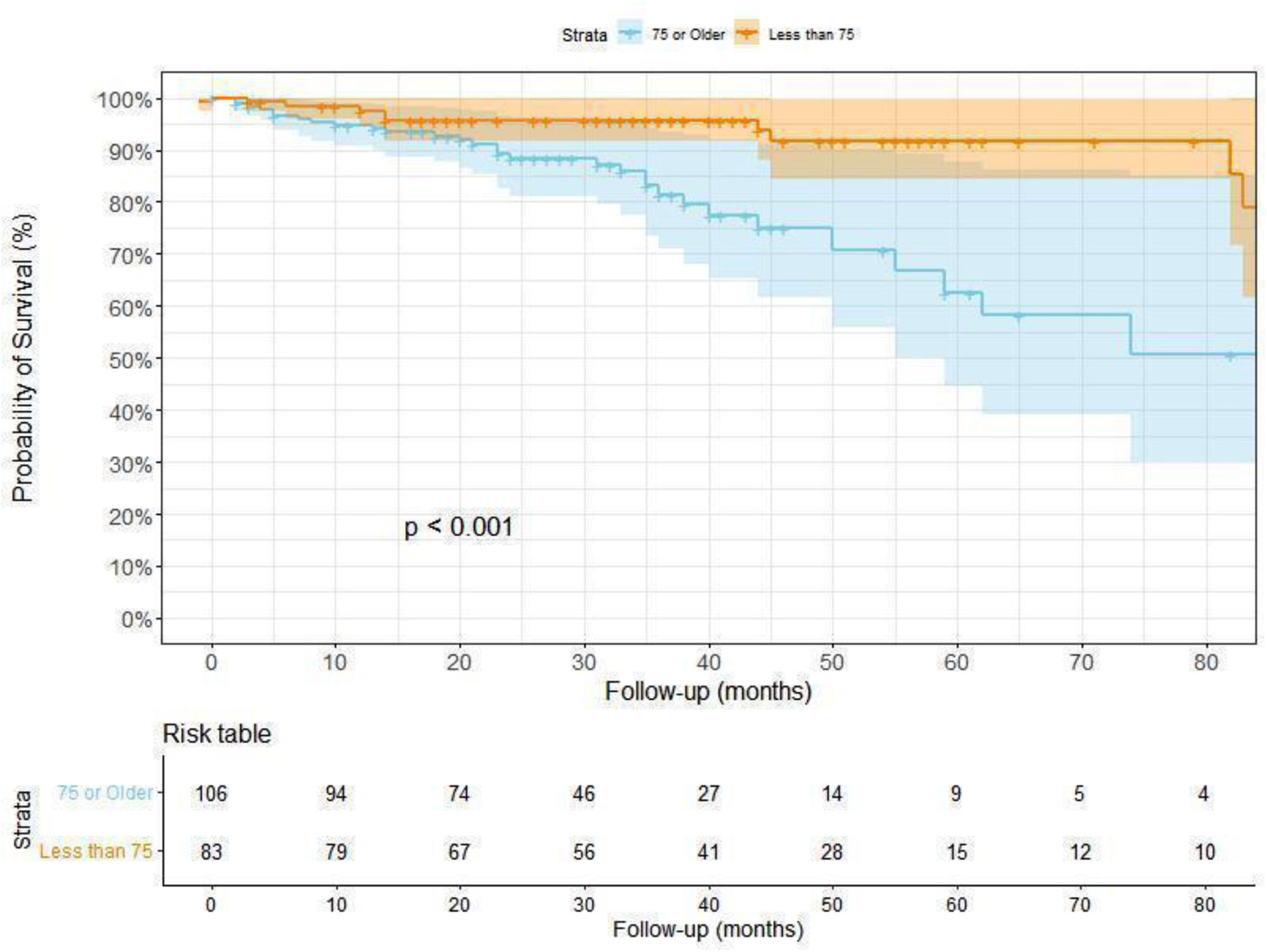

ResultsA total of 232 patients were included in this study. Mean age was 76.3 years (SD 6.5). As per protocol, 69.3% completed the initial assessment but this was lower in the elderly group (61.5%). The most frequent diagnosis was unclassifiable ILD (24.1%), followed by ILD associated with connective tissue disease (21.6%), IPF (12.1%) and hypersensitivity pneumonitis (10.3%). During follow-up (36.7 months (SD 28.6)) a significant proportion of patients died (55 cases, 23.7% of the cohort), especially in the late older group (30.4%). Kaplan–Meier curves showed that those over 75 years have a worse survival even when adjusted by covariables (p<0.001). CPI was the only score with statistical significance in a multivariate analysis (HR 1.06. p 0.006).

ConclusionsOlder adults with ILD featured a distinct clinical profile. Our findings highlight the need to develop non-invasive biomarkers and specific scores adapted to this age-group.

Existen pocos estudios que investiguen el perfil clínico de pacientes mayores con enfermedad pulmonar intersticial difusa (EPID), por lo que este estudio investigó las características de la población mayor diagnosticada con EPID.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo en una población de nuevas derivaciones en una consulta de EPID desde enero de 2013 hasta septiembre de 2017. Se seleccionaron pacientes mayores de 64 años. La recolección de datos incluyó variables de enfermedades, procedimientos diagnósticos y comorbilidades. Se calculó el estadio de género-edad-fisiología (GAP), el índice fisiológico compuesto (CPI) y el índice de Charlson. Se realizó un análisis estadístico para investigar los factores de riesgo asociados con la supervivencia.

ResultadosSe incluyeron en este estudio un total de 232 pacientes. La edad media fue de 76,3 años (DE 6,5). Según el protocolo, el 69,3% completó la evaluación inicial, pero esta fue menor en el grupo de ancianos (61,5%). El diagnóstico más frecuente fue EPID no clasificable (24,1%), seguido de EPID asociada a enfermedad del tejido conectivo (21,6%), FPI (12,1%) y neumonitis por hipersensibilidad (10,3%). Durante el seguimiento (36,7 meses [DE 28,6]) falleció una proporción significativa de pacientes (55 casos, 23,7% de la cohorte), especialmente en el grupo de mayor edad (30,4%). Las curvas de Kaplan-Meier mostraron que los mayores de 75 años tienen una peor supervivencia, incluso cuando se ajusta por covariables (p <0,001). El CPI fue el único índice con significación estadística en un análisis multivariante (HR 1,06, p=0,006).

ConclusionesLos adultos mayores con EPID presentaron un perfil clínico diferenciado. Nuestros hallazgos resaltan la necesidad de desarrollar biomarcadores no invasivos y clasificadores de riesgo específicos adaptados a este grupo de edad.

Interstitial lung diseases (ILD) are a heterogeneous group of non-malignant pulmonary diseases characterized by pathogenic involvement of the interstitium.1 ILD can affect adults of any age, including the older population. In fact, age has been linked with an increased risk of certain entities, especially Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF).2,3 However, there are few studies evaluating the epidemiology of ILD in this group. Petterson et al. showed that those over 70 years old can suffer from different ILD, not only IPF, highlighting the importance of an adequate diagnosis.3 By contrast, invasive procedures are often avoided in this population, leading to an increase of cases labeled as unclassifiable.4 Older patients usually suffer from increased comorbidity (chronic disease health problems) which are associated with poorer quality of life and higher risk of adverse events. For this reason, this population has a higher risk of complications if they undergo invasive procedures and so they are usually avoided. However, this can be translated into age-related discrimination if individual cases are not properly assessed.

Besides, management of older patients with ILD can be challenging, due to frailty, drug toxicity, comorbidities and end of life preferences.5 Aside from age, all these factors can also impact the evolution of the disease, but there is no evidence of a distinct disease behavior in older patients.3 Neither if current prognostic scores are useful in this population. Our hypothesis is that older patients with ILD, especially those over 75 years old, have a distinct clinical profile that impacts their survival, which could not be properly assessed by current scores.

The aim of this study was to investigate the characteristics of older adults diagnosed with ILD along with the predictors of mortality.

Material and methodsStudy designWe performed an observational, retrospective study analysing a cohort of patients referred to an ILD clinic at a university hospital in Spain (Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona), between 2013 and 2017. We followed the STROBE recommendations for observational studies. The study was done in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference for Harmonization. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board (IIBSP-BRO-2015-92). Informed consent was waived due to the nature of the study.

PopulationThe population of the study were new referrals attending an outpatient ILD clinic from January 2013 to September 2017 for evaluation. This is the only one dedicated to this disease in our center, which receives requests mainly from primary care or local pulmonologists. Inclusion criteria were age over 64 years, an available chest high-resolution computerized tomography (HRCT) with findings compatible with ILD and a complete medical history. We excluded those under 65 years old, or with insufficient information to confirm the presence of ILD.

Older adults were defined based on conventional definitions as those with 65 years or more.6 Besides, those between 65 and 74 were classified as “early older” and those over 75 years as “late older”. ILD classification was defined by current international and national guidelines based on clinical, radiological and histology findings.7,8 Based on the same recommendations, following our current practice, all patients were managed under the same diagnostic protocol.9 Invasive procedures were decided in each case tailoring benefits and risks, including lung function values, comorbidities and risks. Besides, patients’ preferences were taken into account to decide about the procedure.10 A final diagnosis was done following a multidisciplinary discussion.11

Data collection and variablesWe collected demographics, co-morbidities, clinical signs, current treatments, smoking history, lung function tests (LFTs), laboratory findings, radiological pattern on HRCT scan, invasive procedures, histology findings and final multidisciplinary diagnosis at the initial evaluation.

Regarding follow-up, we also collected data from the last appointment available, including clinical data, laboratory findings, HRCT scan and lung function tests, and consecutive visits until the last one available. Survival status was checked using a regional database. Reason of death was recorded. We labeled it as respiratory when the cause was related to the disease (progression or exacerbation) or a respiratory comorbidity (like infection, pulmonary embolism, neoplasm, respiratory failure).

At diagnosis, in each case, two IPF risk scores were calculated: Composite physiologic index (CPI) and multidimensional GAP (gender, age and physiology) stage.12,13 CPI was designed to estimate the extent of fibrosis on a thoracic CT through a formula based on lung function values and has been shown to be the best physiological prognosticator in IPF. On the other hand, GAP stage is a baseline mortality prediction model first developed for IPF, that is easily calculated using three variables (age, gender and lung function values). To evaluate the impact of comorbidities, the Charlson comorbidity index and modified Charlson comorbidity index (that includes age) were also measured.14 Charlson index was developed as a weighted index to predict risk of death for patients with specific comorbid conditions.

Statistical analysisA comprehensive statistical analysis was performed to evaluate the characteristics and predictors of mortality among elderly patients diagnosed with interstitial lung disease (ILD).

Descriptive statistics: For all collected variables, a global descriptive analysis was conducted. Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were reported as mean and standard deviation (SD). This descriptive analysis was stratified by age groups (65–75 years and >75 years) and by mortality status (alive or deceased). This stratification aimed to uncover potential differences in demographics, clinical features, and outcomes within these subgroups.

Inferential statisticsThe statistical significance (p-value) between independent groups, age and mortality status, were obtained performing several statistical tests. These included Chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables, and independent samples t-test or Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. These tests were chosen depending on whether it fitted the normal distribution.

Survival analysis: Survival curves, representing the time to death from the first appointment, were generated for the overall population using Kaplan–Meier estimates. These survival analyses were also stratified by age groups and the GAP stage to identify potential differences in survival outcomes based on these factors. p-Value between groups was obtained using log-rank test.

Cox proportional hazards regression: To identify predictors of survival, univariate Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were performed for a range of variables, including demographic and clinical characteristics. The best-fitting multivariate Cox model was determined through a stepwise selection process, which allowed adjustment of the model to include only the most significant predictors. This step aimed to identify independent predictors of mortality, controlling for potential confounding factors. In brief, variables with a p-value<0.2 were selected for further analysis. To address multicollinearity among variables originating from the same conceptual group (e.g., height and BMI), only the variable with the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was retained. Multicollinearity was further assessed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), and variables with VIF>5 were excluded iteratively. If at least 50% of cases in the dataset were complete (i.e., without missing data), a stepwise selection method was applied to construct the initial multivariate Cox model. This process allowed variables to enter or leave the model in either direction (forward and backward) based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Regardless of whether the stepwise selection was applied or not, the resulting model was further refined manually. Variables with a p-value>0.1 were subsequently evaluated and removed iteratively, ensuring that the exclusion of any such variable did not adversely affect the significance of the remaining predictors. This step was necessary because the automated stepwise process may retain variables that do not meet our predefined significance threshold (p<0.1). In cases where less than 50% of the dataset had complete cases, the initial stepwise selection was skipped, and manual elimination of variables with p-values>0.1 was conducted directly from the univariate selection.

We did not include age as an independent variable in the multivariate model because it is already incorporated within the GAP Score, which was included in the analysis. Including both variables simultaneously would lead to multicollinearity, as age is a component of the GAP Score. This redundancy could distort the model coefficients, estimation issues (such as non-convergence of the model or unstable coefficient estimates) and complicate the interpretation of the individual effects of each variable.

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.2.2) with RStudio (version 2022.12.0). p-Value<0.05 was considered statistically significant, ensuring that our conclusions were drawn with a high level of confidence. We used a significance level of 0.05 for the p-values as it is a widely accepted standard in statistical analysis, balancing the risks of Type I (false positive) and Type II (false negative) errors. This threshold provides a reasonable trade-off between detecting true effects and avoiding spurious findings. Using a lower significance level, such as 0.01, would reduce the probability of false positives but at the cost of increasing the likelihood of missing true associations (increased Type II error). Conversely, a higher threshold, like 0.10, would increase sensitivity but also the risk of identifying false associations. The choice of 0.05 also facilitates comparability with a vast body of existing research, making our results more interpretable within the context of established literature.

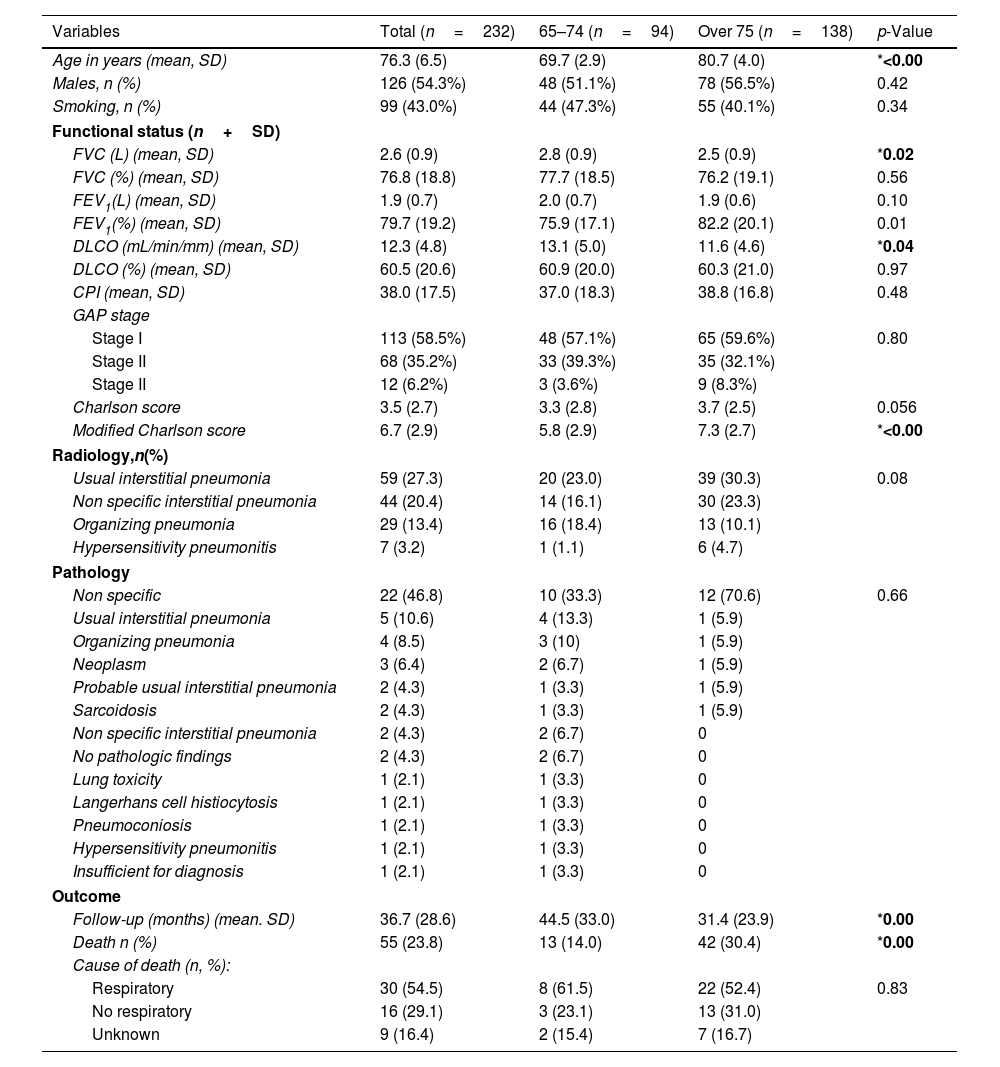

ResultsA total of 232 subjects were finally included in this study. The main demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Mean age was 76.3 years (SD 6.5). There was a slight predominance of men (54.3%) and no smoking history (57%). Regarding LFTs, patients presented with a mild lung function impairment at diagnosis (mean FVC 76.8% and DLCO 60.5%). Those over 75 years old showed lower FVC and DLCO values and higher modified Charlson score values. There were no differences in CPI or GAP score. Different radiological and pathological patterns were observed, with a remarkable proportion of Usual Interstitial Pneumonia (UIP).

Demographics and clinical characteristics of patients included.

| Variables | Total (n=232) | 65–74 (n=94) | Over 75 (n=138) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (mean, SD) | 76.3 (6.5) | 69.7 (2.9) | 80.7 (4.0) | *<0.00 |

| Males, n (%) | 126 (54.3%) | 48 (51.1%) | 78 (56.5%) | 0.42 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 99 (43.0%) | 44 (47.3%) | 55 (40.1%) | 0.34 |

| Functional status (n+SD) | ||||

| FVC (L) (mean, SD) | 2.6 (0.9) | 2.8 (0.9) | 2.5 (0.9) | *0.02 |

| FVC (%) (mean, SD) | 76.8 (18.8) | 77.7 (18.5) | 76.2 (19.1) | 0.56 |

| FEV1(L) (mean, SD) | 1.9 (0.7) | 2.0 (0.7) | 1.9 (0.6) | 0.10 |

| FEV1(%) (mean, SD) | 79.7 (19.2) | 75.9 (17.1) | 82.2 (20.1) | 0.01 |

| DLCO (mL/min/mm) (mean, SD) | 12.3 (4.8) | 13.1 (5.0) | 11.6 (4.6) | *0.04 |

| DLCO (%) (mean, SD) | 60.5 (20.6) | 60.9 (20.0) | 60.3 (21.0) | 0.97 |

| CPI (mean, SD) | 38.0 (17.5) | 37.0 (18.3) | 38.8 (16.8) | 0.48 |

| GAP stage | ||||

| Stage I | 113 (58.5%) | 48 (57.1%) | 65 (59.6%) | 0.80 |

| Stage II | 68 (35.2%) | 33 (39.3%) | 35 (32.1%) | |

| Stage II | 12 (6.2%) | 3 (3.6%) | 9 (8.3%) | |

| Charlson score | 3.5 (2.7) | 3.3 (2.8) | 3.7 (2.5) | 0.056 |

| Modified Charlson score | 6.7 (2.9) | 5.8 (2.9) | 7.3 (2.7) | *<0.00 |

| Radiology,n(%) | ||||

| Usual interstitial pneumonia | 59 (27.3) | 20 (23.0) | 39 (30.3) | 0.08 |

| Non specific interstitial pneumonia | 44 (20.4) | 14 (16.1) | 30 (23.3) | |

| Organizing pneumonia | 29 (13.4) | 16 (18.4) | 13 (10.1) | |

| Hypersensitivity pneumonitis | 7 (3.2) | 1 (1.1) | 6 (4.7) | |

| Pathology | ||||

| Non specific | 22 (46.8) | 10 (33.3) | 12 (70.6) | 0.66 |

| Usual interstitial pneumonia | 5 (10.6) | 4 (13.3) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Organizing pneumonia | 4 (8.5) | 3 (10) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Neoplasm | 3 (6.4) | 2 (6.7) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Probable usual interstitial pneumonia | 2 (4.3) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Sarcoidosis | 2 (4.3) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Non specific interstitial pneumonia | 2 (4.3) | 2 (6.7) | 0 | |

| No pathologic findings | 2 (4.3) | 2 (6.7) | 0 | |

| Lung toxicity | 1 (2.1) | 1 (3.3) | 0 | |

| Langerhans cell histiocytosis | 1 (2.1) | 1 (3.3) | 0 | |

| Pneumoconiosis | 1 (2.1) | 1 (3.3) | 0 | |

| Hypersensitivity pneumonitis | 1 (2.1) | 1 (3.3) | 0 | |

| Insufficient for diagnosis | 1 (2.1) | 1 (3.3) | 0 | |

| Outcome | ||||

| Follow-up (months) (mean. SD) | 36.7 (28.6) | 44.5 (33.0) | 31.4 (23.9) | *0.00 |

| Death n (%) | 55 (23.8) | 13 (14.0) | 42 (30.4) | *0.00 |

| Cause of death (n, %): | ||||

| Respiratory | 30 (54.5) | 8 (61.5) | 22 (52.4) | 0.83 |

| No respiratory | 16 (29.1) | 3 (23.1) | 13 (31.0) | |

| Unknown | 9 (16.4) | 2 (15.4) | 7 (16.7) | |

A significant proportion of cases died during the follow-up (55 cases 23.7% of the cohort), especially in the late older group (30.4%) (Supplementary Material Fig. 1). In the majority the cause of death was respiratory (54.5%). In the group of non-respiratory deaths, cardiovascular complications (including neurological events), neoplasms, dementia or renal failure.

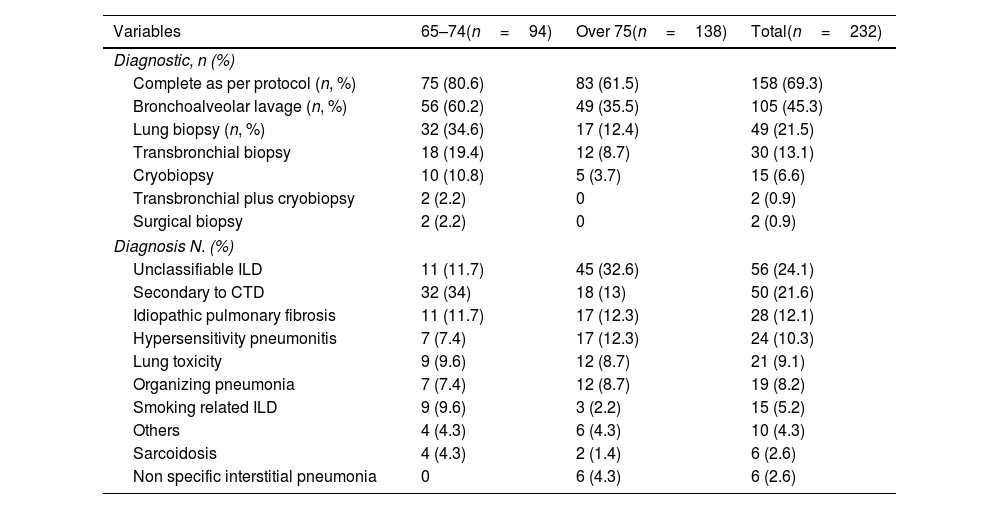

Regarding the diagnosis (Table 2), 69.3% completed the study as per protocol, but this was lower in the late older group (61.5%) (this difference was statistically significant (p .0022) by Fisher's exact test). Bronchoalveolar lavage was performed in a considerable number of patients (45.3%), whereas a lung biopsy was performed in only 21.5%. Indeed, in the late older group was done in only 12.4% and in no case was a surgical biopsy. The most frequent diagnosis was unclassifiable ILD (24.1%), influenced by the late older group (32.6%), followed by ILD associate to connective tissue disease (CTD-ILD) (21.6%), IPF (12.1%) and hypersensitivity pneumonitis (10.3%).

Diagnostic procedures and final multidisciplinary diagnosis.

| Variables | 65–74(n=94) | Over 75(n=138) | Total(n=232) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic, n (%) | |||

| Complete as per protocol (n, %) | 75 (80.6) | 83 (61.5) | 158 (69.3) |

| Bronchoalveolar lavage (n, %) | 56 (60.2) | 49 (35.5) | 105 (45.3) |

| Lung biopsy (n, %) | 32 (34.6) | 17 (12.4) | 49 (21.5) |

| Transbronchial biopsy | 18 (19.4) | 12 (8.7) | 30 (13.1) |

| Cryobiopsy | 10 (10.8) | 5 (3.7) | 15 (6.6) |

| Transbronchial plus cryobiopsy | 2 (2.2) | 0 | 2 (0.9) |

| Surgical biopsy | 2 (2.2) | 0 | 2 (0.9) |

| Diagnosis N. (%) | |||

| Unclassifiable ILD | 11 (11.7) | 45 (32.6) | 56 (24.1) |

| Secondary to CTD | 32 (34) | 18 (13) | 50 (21.6) |

| Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | 11 (11.7) | 17 (12.3) | 28 (12.1) |

| Hypersensitivity pneumonitis | 7 (7.4) | 17 (12.3) | 24 (10.3) |

| Lung toxicity | 9 (9.6) | 12 (8.7) | 21 (9.1) |

| Organizing pneumonia | 7 (7.4) | 12 (8.7) | 19 (8.2) |

| Smoking related ILD | 9 (9.6) | 3 (2.2) | 15 (5.2) |

| Others | 4 (4.3) | 6 (4.3) | 10 (4.3) |

| Sarcoidosis | 4 (4.3) | 2 (1.4) | 6 (2.6) |

| Non specific interstitial pneumonia | 0 | 6 (4.3) | 6 (2.6) |

ILD: interstitial lung disease; CTD: connective tissue disease.

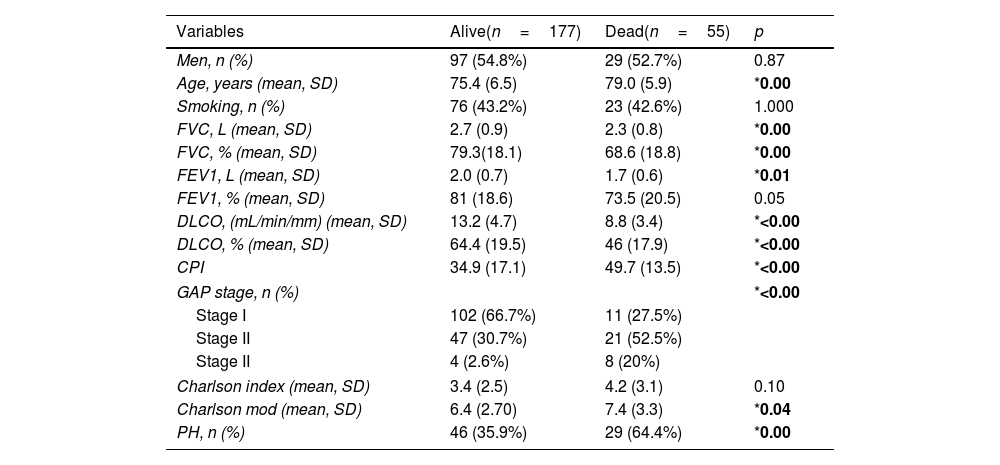

The clinical profile of patients with a fatal outcome (death) was different from those alive (Table 3). Aside from age, as expected, lung function values were lower in that group. Differences were also found in CPI, GAP stage, modified Charlson score or pulmonary hypertension. Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that those over 75 years have worse survival, even when adjusted to covariables, compared to those below 75 years (p<0.001) (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of patients depending on survival status.

| Variables | Alive(n=177) | Dead(n=55) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men, n (%) | 97 (54.8%) | 29 (52.7%) | 0.87 |

| Age, years (mean, SD) | 75.4 (6.5) | 79.0 (5.9) | *0.00 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 76 (43.2%) | 23 (42.6%) | 1.000 |

| FVC, L (mean, SD) | 2.7 (0.9) | 2.3 (0.8) | *0.00 |

| FVC, % (mean, SD) | 79.3(18.1) | 68.6 (18.8) | *0.00 |

| FEV1, L (mean, SD) | 2.0 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.6) | *0.01 |

| FEV1, % (mean, SD) | 81 (18.6) | 73.5 (20.5) | 0.05 |

| DLCO, (mL/min/mm) (mean, SD) | 13.2 (4.7) | 8.8 (3.4) | *<0.00 |

| DLCO, % (mean, SD) | 64.4 (19.5) | 46 (17.9) | *<0.00 |

| CPI | 34.9 (17.1) | 49.7 (13.5) | *<0.00 |

| GAP stage, n (%) | *<0.00 | ||

| Stage I | 102 (66.7%) | 11 (27.5%) | |

| Stage II | 47 (30.7%) | 21 (52.5%) | |

| Stage II | 4 (2.6%) | 8 (20%) | |

| Charlson index (mean, SD) | 3.4 (2.5) | 4.2 (3.1) | 0.10 |

| Charlson mod (mean, SD) | 6.4 (2.70) | 7.4 (3.3) | *0.04 |

| PH, n (%) | 46 (35.9%) | 29 (64.4%) | *0.00 |

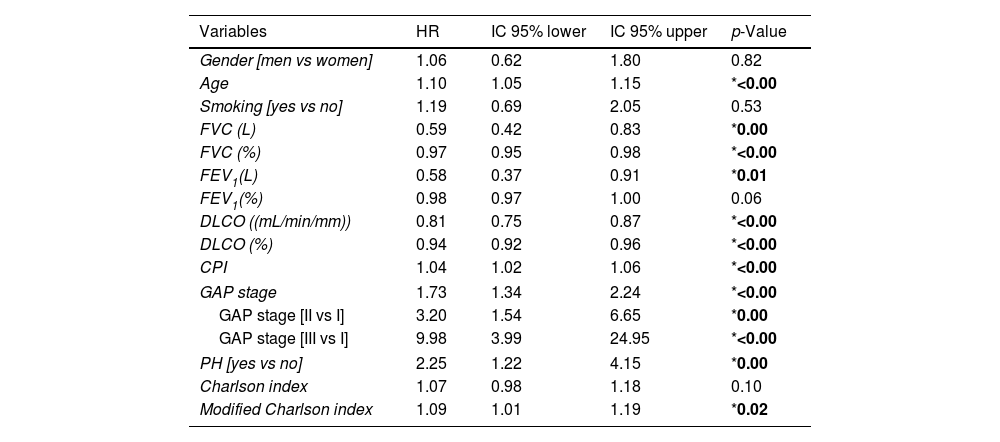

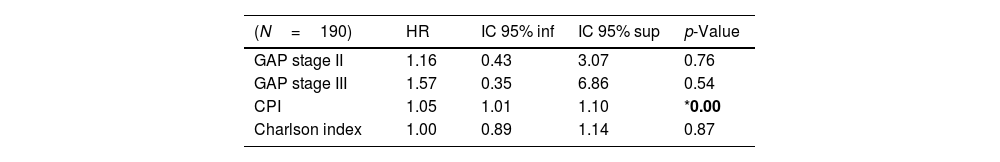

Regarding risk factors associated with mortality, univariate analysis showed correlation with various variables (Table 4), most of them previously described as risk factors in ILD, such as age, lung function (FVC and DLCO) or pulmonary hypertension. A multivariate analysis including the predefined variables (GAP, CPI, Charlson score) showed that CPI was the only one with statistical significance (HR 1.06. p 0.006) (Table 5), even when adjusted to other covariables (Supplementary Material Table 1).

Univariate Cox regression analyses.

| Variables | HR | IC 95% lower | IC 95% upper | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender [men vs women] | 1.06 | 0.62 | 1.80 | 0.82 |

| Age | 1.10 | 1.05 | 1.15 | *<0.00 |

| Smoking [yes vs no] | 1.19 | 0.69 | 2.05 | 0.53 |

| FVC (L) | 0.59 | 0.42 | 0.83 | *0.00 |

| FVC (%) | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.98 | *<0.00 |

| FEV1(L) | 0.58 | 0.37 | 0.91 | *0.01 |

| FEV1(%) | 0.98 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.06 |

| DLCO ((mL/min/mm)) | 0.81 | 0.75 | 0.87 | *<0.00 |

| DLCO (%) | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.96 | *<0.00 |

| CPI | 1.04 | 1.02 | 1.06 | *<0.00 |

| GAP stage | 1.73 | 1.34 | 2.24 | *<0.00 |

| GAP stage [II vs I] | 3.20 | 1.54 | 6.65 | *0.00 |

| GAP stage [III vs I] | 9.98 | 3.99 | 24.95 | *<0.00 |

| PH [yes vs no] | 2.25 | 1.22 | 4.15 | *0.00 |

| Charlson index | 1.07 | 0.98 | 1.18 | 0.10 |

| Modified Charlson index | 1.09 | 1.01 | 1.19 | *0.02 |

Multivariate Cox regression analyses adjusted by CPI, Charlson and GAP stage.

| (N=190) | HR | IC 95% inf | IC 95% sup | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAP stage II | 1.16 | 0.43 | 3.07 | 0.76 |

| GAP stage III | 1.57 | 0.35 | 6.86 | 0.54 |

| CPI | 1.05 | 1.01 | 1.10 | *0.00 |

| Charlson index | 1.00 | 0.89 | 1.14 | 0.87 |

In this study about older patients with ILD, we found a distinct clinical profile depending on age at diagnosis. Those over 75 years old had higher risk of mortality and were less fit to complete the diagnostic protocol. This leads to a higher proportion of unclassifiable ILD. Concerning risk scores, CPI seems to be the one that independently better predicts the risk of mortality in this cohort.

The diagnosis of ILD is currently based on multidisciplinary discussion of the main findings, including medical history, blood tests, HRCT scan and, if available, data from invasive procedures, such a bronchoscopy or lung biopsy.15 Unfortunately, if recommended, not all patients agree or are suitable enough for invasive procedures.16 These cases are labeled as unclassifiable. In fact, our data showed that a significant proportion of older patients, especially those over 75 years old, are finally labeled as unclassifiable. On the other hand, our results are in line with those reported by Petterson.3 This study showed that in this population although IPF is one the most frequent diagnosis (34%), there were a wide range of entities, including CTD-ILD (11%) and hypersensitivity pneumonitis (8%). Therefore, putting together these results, there is a need to develop non-invasive biomarkers able to help in the diagnosis in this age-group, as invasive procedures are not warranted.17,18

In the field of ILD, there has been an enormous interest in unraveling those factors linked to the risk of mortality.19 Many studies have identified age, lung function values, pattern and extension of fibrosis on chest HRCT scan or comorbidities as relevant biomarkers.19 In our cohort, a significant proportion of patients died during follow-up (23.8%). This was even higher in the late older group (30.4%). Interestingly, in the majority, the cause of death was respiratory. Univariate analysis showed that many of those variables cited previously were also related to mortality. Those patients over 75 years have a worse survival rate although there were minor differences in the demographics of both groups. This suggests that, in this population, there are other variables, probably linked with aging, that impact on the behavior of the disease.

GAP stage was developed as a model to predict baseline mortality in IPF, and later investigated in other ILDs.20 The model is based on age and lung function (FVC and DLCO).12 CPI was developed to quantify the extension of fibrosis using only lung function values, providing better prognostic information than isolated lung values. However, these scores were investigated in a younger population compared to our cohort (GAP score 69.7 years in the derivation cohort, 66.3 years in the validation cohort; CPI score: derivation cohort 61.8 years, validation cohort 62.6 years). By contrast, the Charlson Comorbidity Index was developed to classify comorbid conditions which may influence the risk of mortality. As older patients have more comorbidities, we decided to include this score in our analysis. In the univariate analysis, our data showed that these scores were related to mortality. But in the multivariate analysis, only CPI retains statistical significance. We attributed this to the design of CPI that is related to disease extension. Several research studies have shown that fibrosis extension measured on HRCT scans has a significant impact on patients’ prognosis. But this variable is not used in clinical practice due to lack of standardization. So CPI is an alternative to calculate this variable. On the other hand, comorbidities may play a role in prognosis. Frailty, sarcopenia or drug reactions are common in older patients,21–24 but this is not included in the Charlson score. So, our results show the limited value of these scores in the older population with ILD and the need to design specific scores adapted to the requirements of these populations.

This study has several limitations. Most of them are due to the nature of the study. The retrospective analysis implies that when collecting the data some information could be missing. Besides, as the study is based on one hospital experience, there is a limitation in the extrapolation of the data. The lack of quantification of extension of the disease at HRCT is also a limitation. Finally, there is no data of other important factors related to mortality in this population, such as frailty, sarcopenia or malnutrition.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, the results of this study show that older adults with ILD featured a distinct clinical profile. This population suffers from a variety of entities, but a significant proportion remains unclassifiable. Age has an impact in mortality but also in diagnosis, mainly due to the absence of invasive diagnostic procedures. Our findings highlight the need to develop non-invasive biomarkers and specific scores adapted to this age-group. Prospective studies are needed to understand the needs of older patients with ILD.

FundingThis research has not received specific aid from agencies from the public sector, commercial sector or non-profit entities.

Authors’ contributionsConceptualization, L.F-M, S.O. and D.C.; methodology, L.F-M, S.O., P.M. and D.C; data curation, L.F-M, S.O. and G.R.; writing—original draft preparation, L.F-M, S.O. and D.C.; writing—review and editing, all authors; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interestDr. Castillo reports grants and personal fees from Boehringer-Ingelheim, personal fees from Veracyte, grants from Fujirebio, outside the submitted work. The others authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors would like to thank the patients for their continued fight against this disease.