To present our results and describe the technique used for the endovascular treatment of haemorrhoids.

Material and methodsWe used right femoral artery or radial artery access to catheterize the inferior mesenteric artery, proceeding to the superior rectal artery with a 2.7F microcatheter to catheterize and embolise each distal branch distally with PVA particles (300–500μm) and proximally with coils (2–3mm). Patients were discharged 24h after the procedure and clinically followed up at one month by anoscopy.

ResultsWe included 20 patients (4 women and 16 men); mean age, 61.85 years (27–81 years); mean follow-up, 10.6 months (28–2 months). Technical success was achieved in 18 (90%) patients and clinical success in 15 (83.4%); one patient required a second embolisation of the medial rectal artery and two required surgery. Recovery was practically painless. At the one-month follow-up, all patients were very satisfied and anoscopy demonstrated marked improvement of the haemorrhoids. There were no complications secondary to embolisation.

ConclusionsOur initial results suggest that selective intra-arterial embolisation is a safe and painless procedure that is well tolerated because it avoids rectal trauma and patients recover immediately.

El objetivo de este trabajo es presentar nuestros resultados, describiendo la técnica utilizada en el tratamiento endovascular de las hemorroides.

Material y MétodoLa embolización se realizó mediante punción de la arteria femoral derecha o vía arteria radial, y se cateterizó la arteria mesentérica inferior (AMI) accediéndose a la arteria rectal superior con un microcatéter (2,7 F) con el que cateterizábamos cada rama distal, ocluyéndolas distalmente con partículas de PVA (300-500 micras), y proximalmente con coils de 2-3mm. Los pacientes recibieron el alta a las 24 horas, al mes se les evaluó clínicamente y se les realizó una anoscopia.

ResultadosEl estudio incluye 20 pacientes. (4 mujeres y 16 hombres), edad media de 61,85 años (27-81), con seguimiento medio de 10,6 meses (rango de 28-2 meses). El éxito técnico fue del 90% (18/20) y el éxito clínico de 83,4% (15/18); un paciente requirió nueva embolización de la arteria rectal media y dos pacientes requirieron cirugía. La recuperación fue prácticamente indolora. Al mes todos referían gran satisfacción y la anoscopia demostraba importante mejoría de las hemorroides. No hubo complicaciones secundarias a la embolización.

ConclusionesLos resultados iniciales sugieren que la ESARS es un procedimiento seguro e indoloro, bien tolerado que evita el trauma anorrectal, y recuperación inmediata del paciente.

Haemorrhoidal disease is currently the most common anorectal disorder, with a prevalence of 4%–35% of the population. In most cases it manifests as varying degrees of rectal bleeding, with only 10% requiring surgical treatment.1

Up to now, the reference surgical technique has been the Milligan–Morgan technique, which is essentially open haemorrhoidectomy.2 Since 1990 there have been descriptions in the scientific literature of new surgical techniques aimed at reducing post-surgical pain and achieving complete recovery of the patient in less time. The circular anopexia described by Longo3 reduces the number of days in hospital and the pain is less intense. However, the reported recurrence rates are as high as 15–20% of cases.4

Among the non-excision surgical techniques, ligation of the haemorrhoidal arteries in the distal rectum by Doppler-guided transanal haemorrhoidal dearterialisation (THD Doppler procedure) is associated with less postoperative pain compared to classic surgical techniques and without adverse events in terms of postoperative complications.5,6

The development of interventional endovascular techniques offers the chance to perform intra-arterial embolisations (IAE) to occlude the superior rectal artery. The advantages of this intra-arterial embolisation technique over transanal haemorrhoidal dearterialisation include the fact that all branches dependent on the superior rectal artery can be identified and therefore embolised, and it is even possible to occlude any anastomoses with the middle rectal artery, thereby removing the risk of rectal trauma.7,8 Coil embolisation of the superior rectal artery is a well tolerated, effective and safe technique.9,10

The aim of this paper is to present our results, describing the technique used in the endovascular treatment of haemorrhoids.

Material and methodsThis was a retrospective observational study conducted in our hospital and approved by the Research Committee. Informed consent was obtained from each patient.

From September 2017 to April 2019, we included 20 patients with grade II or III haemorrhoidal disease visualised by anoscope or proctoscope, accompanied by significant rectal bleeding (Table 1).

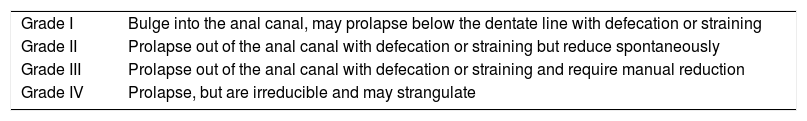

Goligher classification of internal haemorrhoids.

| Grade I | Bulge into the anal canal, may prolapse below the dentate line with defecation or straining |

| Grade II | Prolapse out of the anal canal with defecation or straining but reduce spontaneously |

| Grade III | Prolapse out of the anal canal with defecation or straining and require manual reduction |

| Grade IV | Prolapse, but are irreducible and may strangulate |

The patients attended the colorectal surgery outpatient clinic, where their medical history was taken and the examination performed. Patients who had contraindications for surgery, refused surgery or had recurrence after a previous intervention were offered the option of superior rectal artery embolisation.

The procedure was performed in a room equipped with a digital angiograph under aseptic conditions.

Patients were admitted fasting on the same morning and blood was taken for a coagulation study. Once adequate haemostasis was confirmed, the procedure was performed with conscious sedation and local anaesthetic to the puncture site.

After puncture of the right common femoral artery, an abdominal aortic angiogram was performed using a 5F introducer (Radiofocus, Terumo, Japan) with a 5F pig-tail catheter to locate the inferior mesenteric artery or, more frequently with the arch in the lateral position, it was selectively catheterised with Simmons 2 5F catheter (Radiofocus, Terumo, Japan) or MIK 5F catheter (Boston Scientific, USA) and hydrophilic tip. A Direxion 2.4F microcatheter (Boston Scientific, USA) was then introduced coaxially for superselective catheterisation of the superior rectal artery and its anterior, posterior and right branches.

In each branch of the artery we administered 1ml of 300–500μm polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particles (BTG, Boston Scientific, USA) to occlude the plexus, subsequently embolising all arterial pedicles with 2–3mm coils (Interlock-18 Fibered IDC, Boston Scientific, USA or Nester, Cook Medical. DK). The patients remained in hospital for 24h.

A follow-up anoscope examination was performed during the admission, at discharge and at the outpatient clinic at one month, with the medical checks then being repeated every three months. Patients were assessed for discomfort or pain after the procedure using the visual analogue scale at rest (VASR), whether bleeding persisted and, by anoscope examination, the degree of engorgement of the haemorrhoid bundle. In the case of persistence of symptoms, patients were reviewed both clinically and by proctoscope examination and the subsequent approach reassessed.

The procedure was considered to be a technical success when all arterial pedicles were suitably embolised and a clinical success when patients had no more bleeding within a month of the embolisation.

In three of the last cases we started the procedure using radial puncture as approach technique. The puncture was performed on a single arterial wall with ultrasound guidance with a 0.018 arterial micropuncture set; then a 120cm-long multipurpose 4F catheter (Cordis) was used, with a 150cm-long Direxion microcatheter (2.7F) (Boston Scientific, USA). To avoid arterial spasm, 3000IU of sodium heparin and 200μg of intra-arterial Solinitrina [glyceryl trinitrate] was administered. Once the guide reached the aorta, a 50cm-long 5F Flexor introducer was inserted and the inferior mesenteric artery was catheterised and embolised using the technique described above.

The measurement of the radiation received by the patient expressed in dose/area (mGy/cm2) was considered important.

A descriptive analysis of the variables included is provided: measures of central tendency and dispersion, as well as absolute and relative frequencies expressed as percentages.

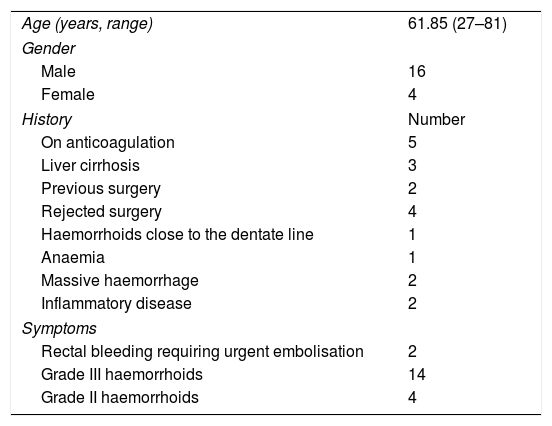

ResultsThe study included 20 symptomatic patients (16 males and 4 females) with grade II and III bleeding haemorrhoids and a mean age of 61.85 (27–81). Two patients had previously undergone haemorrhoidectomy.

The technical success of embolisation of the superior rectal artery was obtained in 18 (90%) of the 20 patients. Clinical success was achieved in 15 (83.4%) out of 18, as one patient required a further embolisation due to recurrence of bleeding and two patients had acute bleeding one month later, requiring surgical intervention.

The mean follow-up of the patients was 10.6 months (range 2–18 months).

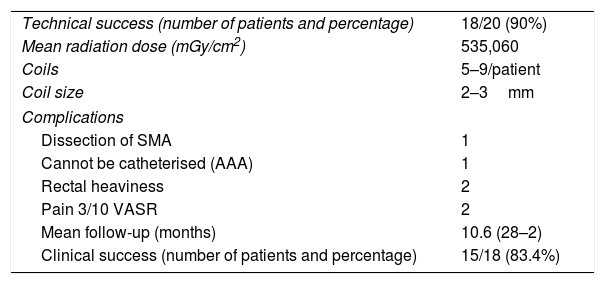

Tables 2 and 3 show the demographic characteristics and the outcomes after embolisation.

Demographic characteristics of the treated patients (N=20).

| Age (years, range) | 61.85 (27–81) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 16 |

| Female | 4 |

| History | Number |

| On anticoagulation | 5 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 3 |

| Previous surgery | 2 |

| Rejected surgery | 4 |

| Haemorrhoids close to the dentate line | 1 |

| Anaemia | 1 |

| Massive haemorrhage | 2 |

| Inflammatory disease | 2 |

| Symptoms | |

| Rectal bleeding requiring urgent embolisation | 2 |

| Grade III haemorrhoids | 14 |

| Grade II haemorrhoids | 4 |

Treatment and outcomes.

| Technical success (number of patients and percentage) | 18/20 (90%) |

| Mean radiation dose (mGy/cm2) | 535,060 |

| Coils | 5–9/patient |

| Coil size | 2–3mm |

| Complications | |

| Dissection of SMA | 1 |

| Cannot be catheterised (AAA) | 1 |

| Rectal heaviness | 2 |

| Pain 3/10 VASR | 2 |

| Mean follow-up (months) | 10.6 (28–2) |

| Clinical success (number of patients and percentage) | 15/18 (83.4%) |

AAA: abdominal aortic aneurysm; SMA: superior mesenteric artery; VAS: visual analogue scale.

During the embolisation procedure the middle rectal artery was identified in 14 of the 20 patients and was occluded after administration of particles.

The patients who were embolised by femoral approach were discharged at 24h, and the three patients in whom we performed radial puncture were discharged 6h after the procedure. Two patients developed rectal pain after the treatment, which disappeared within a few hours after the administration of 1g of paracetamol intravenously. Two patients reported a certain degree of rectal heaviness, but did not identify it as pain and it did not require treatment.

There were no immediate major complications.

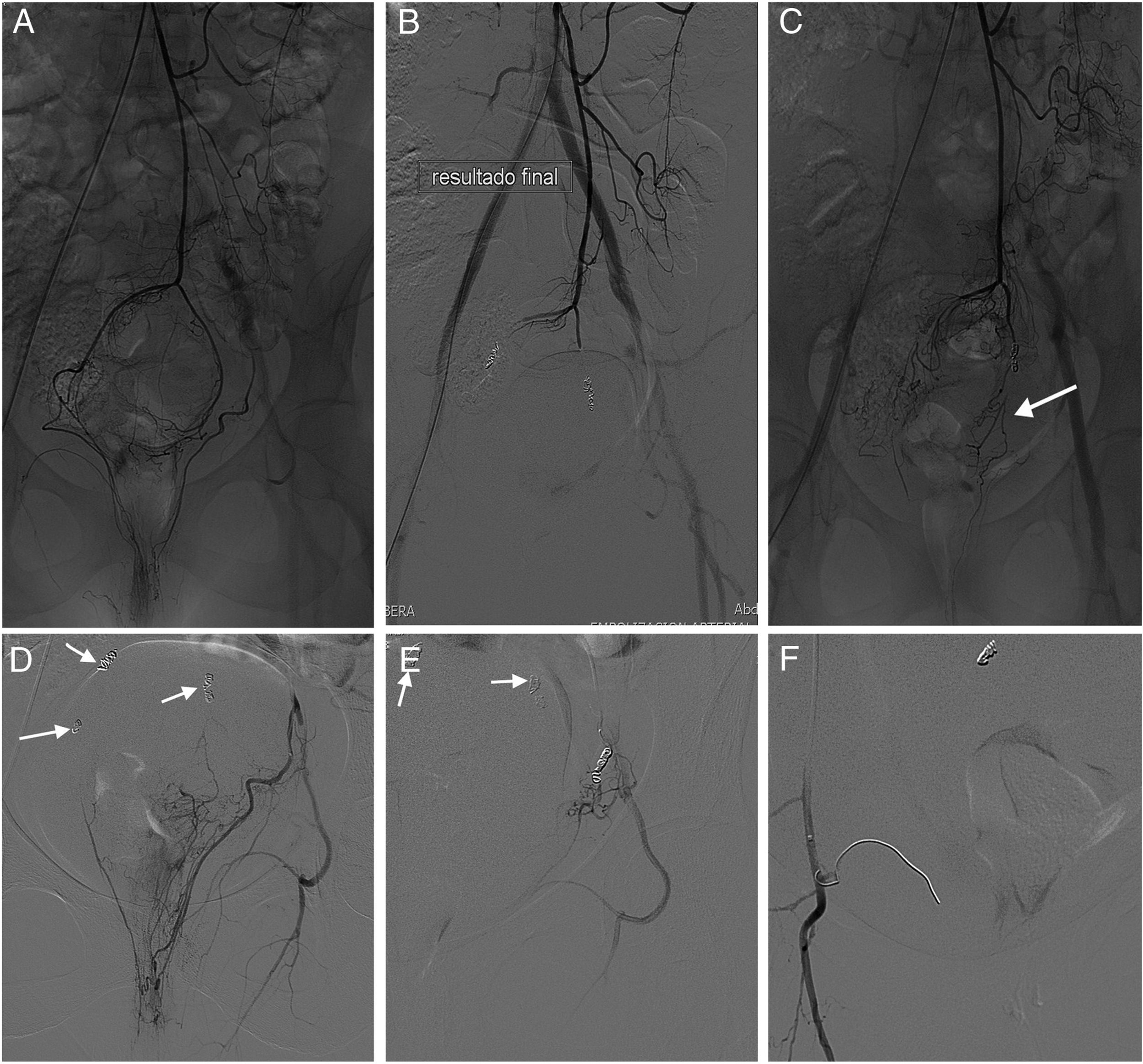

There were three patients with clinical failure; one had recurrence of bleeding eight months post-embolisation, so it was decided to repeat the procedure. Catheterisation of the superior rectal artery showed occlusion of all branches, but there was evidence of restoration of the blood supply to the haemorrhoidal plexus through the middle rectal arteries, predominantly the left middle rectal artery. This finding meant that they had to be catheterised and embolised with coils (Fig. 1). Two other patients required surgery one month after embolisation due to recurrence of bleeding. In one of these patients (who was embolised as an emergency), bleeding in a jet was detected in the anal canal from the right lower haemorrhoidal pedicle which was treated with two transfixion sutures.

43-Year-old woman with anaemia due to bleeding haemorrhoids. (A) Selective arteriogram of the superior rectal artery, which shows the division in the distal branches and the haemorrhoidal plexus. (B) Final result after embolisation of each branch with 300–500μm PVA particles and subsequent occlusion of each branch with 2 and 3mm-diameter coils. Good clinical outcome with cessation of rectal bleeding. (C) At 8 months, recurrence of bleeding so a further embolisation is decided on. Catheterisation of the superior rectal artery demonstrates the correct occlusion of its branches. Restoration of blood flow to the haemorrhoidal plexus through dependent branches of the middle rectal artery (arrow) is detected. (D) Catheterisation of the branches of the left middle rectal artery is responsible for the continued vascularisation of the haemorrhoidal plexus. The arrows show the coils from the previous embolisation of the branches of the superior rectal artery. (E) Image showing the result after coil embolisation of the left middle rectal artery; the arrows show the coils from the previous embolisation. (F) Result after coil embolisation of the right middle rectal artery (arrow). Because the diameter of the artery is less than 2mm, the coil is fully unfurled.

The two cases of technical failure were caused by: (a) dissection of the inferior mesenteric artery in one patient when the MIK 5F catheter was introduced, which prevented it from being advanced despite the administration of intra-arterial vasodilators (the patient is currently asymptomatic and has no rectal bleeding): and (b) an infrarenal aortic aneurysm in the other patient, which we were unaware of, making catheterisation of the inferior mesenteric artery impossible.

One patient, who suffered from Crohn's disease, had a large haemorrhoid with almost daily rectal bleeding, and was found to have a substantial haemorrhoid bundle and a large drainage vein (Fig. 2). Although the embolisation was technically successful, the patient continued to have rectal bleeding for three weeks. However, the bleeding subsequently ceased spontaneously, so we considered it to be a clinical success.

27-Year-old male with Crohn's disease who has daily episodes of rectal bleeding. (A) The selective arteriogram of the superior rectal artery shows increased lumen in the distal branches and obvious staining of the haemorrhoidal cushions. (B) The large diameter of the drainage vein (arrow) indicates the extent of the haemorrhoidal congestion. (C) Final result with all the dependent branches of the superior rectal artery occluded with particles and 2 and 3mm-diameter coils.

In all the cases embolised successfully, proctoscope examination one month post-embolisation showed the marked decrease or total collapse of the haemorrhoid bundle, which was maintained at subsequent follow-ups.

The mean radiation dose was 535,060mGy/cm2, with a range of 66,532–1,445,794mGy/cm2. The patients with radial access received a higher dose (mean 743,370.33mGy/cm2, range 1,378,270–67,524mGy/cm2) than those with femoral access, who received 514,244.60mGy/cm2 (range 811,687–66,532mGy/cm2).

DiscussionIn recent years, the published results on the endovascular treatment of haemorrhoids suggest a very encouraging alternative to conventional surgery.8,9,11,12 The findings and results of our study corroborate the benefits of using this procedure, as an end to rectal bleeding is achieved in a high percentage of cases and the postoperative period is virtually painless.

Haemorrhoids are classified into internal and external haemorrhoids according to their location above or below the dentate line. In the case of internal haemorrhoids, the Goligher classification is used, based on their degree of prolapse13 (Table 1).

The main symptom of internal haemorrhoids is rectal bleeding and recurrence can affect quality of life and cause anaemia. The first step for treatment includes dietary and hygiene measures; surgical treatment is only necessary in 10% of cases.

The Milligan–Morgan haemorrhoidectomy technique is based on the surgical excision of engorged haemorrhoid bundles or those presenting symptoms, with proximal ligation of the plexus. This is the reference technique and it has a cure rate close to 95%, but it also has a 75% incidence of postoperative pain, which can last from 1–4 weeks, and patients can even be incapacitated for daily activities.2,13

We know from the studies by Aigner in 200614 that the superior rectal arteries in patients with haemorrhoids have larger lumens and higher flow rates. This study was performed with transperineal Doppler ultrasound. The findings for patients with symptomatic haemorrhoids were compared with those of the control group (patients without haemorrhoids), confirming that the difference was statistically significant and corroborating the idea of the arterial vascular nature of haemorrhoids.

In the quest for less postoperative pain, other techniques have been developed that reduce discomfort after the procedure. The most recent is transanal haemorrhoidal dearterialisation (THD), which consists of Doppler-guided dearterialisation through ligation of the branches of the superior rectal artery. The intervention is performed by detecting the arteries with the Doppler and ligating them in the upper part of the rectal canal. If there is prolapse of the haemorrhoidal mucosa, the same points are used to perform mucosal plication, lifting the muscles of the anal canal and reducing the prolapse.4

In 2014, as an alternative to surgery, Vidal described the “Emborrhoid” technique, consisting of selective embolisation of the superior rectal arteries to decrease hyperflow to the haemorrhoid cushions.7,8 The patients were not suitable for surgical techniques either because of serious coagulation disorders, previous rectal surgery or liver cirrhosis. At one month, the technical success rate was 100% and they had a clinical success rate of 72%. The postoperative period was painless and there were no ischaemic complications.

Following on from that publication with promising results, Zakharchenco et al.11 published a series of 40 patients treated with IAE with microparticles and coils, with symptom resolution rates of 83% and 94% with grade III and I–II haemorrhoids respectively. The better results are attributed to the fact that with the administration of particles between 300 and 500μm in size, the haemorrhoidal plexus is embolised distally, as recurrence of bleeding takes place through the middle rectal artery and even the lower rectal artery due to anastomosis with the superior rectal artery; a finding made by the authors in 20–40% of patients. This working group differed in that placement of the coils was in the main branch of the superior rectal artery, unlike Vidal et al, who occluded each terminal branch with coils.

Like Zakharchenco et al., our working group uses prior embolisation with PVA particles, but we embolise each distal branch of the superior rectal artery with coils. We support our administration of 1ml of particles distally with the fact of having identified the middle rectal artery in 70% of cases and the inferior rectal artery in 20% of those. In cases of recurrence of bleeding, restoration of the blood supply was only by way of the middle rectal artery, the distal branches of the superior rectal artery being completely embolised. Zakharchenco et al. stressed that, in addition to coils, particle embolisation was a safe technique and did not cause ischaemia. They defined clinical success as decreased anal discomfort and cessation of bleeding and pain in 83% of grade III haemorrhoids and 94% of grade II and I haemorrhoids. Histopathology analysis of mucosa from the rectum and the basement membrane one day and one month after the procedure showed no mucosal atrophy or dystrophy. They also studied sphincters by sphincterometry, concluding that both the external and internal sphincters showed normal contractility in all patients. There were also no changes in electromyography, and the Doppler ultrasound showed no differences in the different types of mucosa, although there was a significant decrease in flow in the haemorrhoidal plexus.11

In Spain, the first three cases embolised with coils were published with good technical and clinical outcomes; IAE was proposed in cases of inflammatory bowel disease, as the rate of complications in haemorrhoidectomy in patients with Crohn's disease ranges from 15% to 40%.12

More recently, Tradi et al.15 published a series of 25 patients with grade II and III haemorrhoids treated with coil embolisation of the superior rectal arteries, with a clinical success rate at 12 months of 72%.

The indications for this endovascular treatment have yet to be established. Our group proposes that intra-arterial embolisation of the superior rectal artery for the treatment of symptomatic internal haemorrhoids is indicated in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, patients with bleeding disorders or on anticoagulation therapy, patients with morbid obesity, patients with paraplegia, patients with previous surgery in the anorectal area, patients with haemorrhoids below the dentate line and patients who reject surgery. We believe it should be contraindicated in patients with aneurysm in the infrarenal aorta and patients with prolapsed haemorrhoids, in whom embolisation fails to reduce the prolapse.

In our patients, proctoscopy one month after embolisation showed, in all the successfully embolised cases, the collapse of the haemorrhoid bundle with no evidence of ischaemia in the wall of the rectum.

The clinical success rate in our series (83.4%) was slightly higher than in other published series,7,15 and we attribute this to the combined effect of the administration of particles and coils in each pedicle. Although Zakharchenco et al.11 reported a higher clinical success rate (83% in grade III haemorrhoids and 94% in grade I and II), this was not well defined as, in addition to cessation of bleeding, it included in the percentage both the decrease in anal discomfort and patient satisfaction. Tradi had a clinical success rate of 72%, occluding the arteries with coils and without using particles.15

It is true that our procedure takes longer, increasing the radiation dose received by the patient, which we believe is too high. However, the same applies to the radial approach (despite having included only three patients) as, although it has the advantage that the patient can be discharged within hours, it also increases the embolisation time and, consequently, radiation exposure. Other recently published studies show mean radiation exposure similar to ours.15 Nonetheless, we believe that this aspect should be considered as a drawback of the treatment, especially when we are treating young patients. That is why we are currently minimising the radiation dose using the scope, “roadmapping” and avoiding serial imaging tests as far as possible.

We do not believe that a prior CT-angiogram is necessary; it increases the dose of radiation received and does not provide any benefits in terms of the images, as all the distal branches of the superior rectal artery can be identified from oblique views on the arteriogram.

Like other authors, we do believe that the main advantage of endovascular treatment of haemorrhoids is the practically painless postoperative period; as it is so well tolerated, patients can get back to normal much more quickly.

In our series, only two patients felt pain, which lasted less than 24h and was controlled with oral analgesia. Another patient reported a “feeling of heaviness” in the rectal area, but this also disappeared within 24h.

Our study does have many limitations, particularly the number of cases and the limited follow-up. We believe that larger studies are needed to confirm the effectiveness of the technique, define the indications and adjust the procedure, in order to determine whether embolisation with coils alone is best or whether the outcome would be improved by the addition of particles.

In conclusion, the results from our patients support the use of particles plus coils in the embolisation of bleeding haemorrhoids, with a well-tolerated post-procedure period and good initial outcomes.

Authorship- 1.

Responsible for the integrity of the study: MDFP, EEH, FJBG, RRG and JSS.

- 2.

Study conception: MDFP, EEH, FJBG, RRG and JSS.

- 3.

Study design: MDFP, EEH, FJBG, RRG and JSS.

- 4.

Data acquisition: MDFP, EEH, FJBG, RRG and JSS.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: MDFP, EEH, FJBG, RRG and JSS.

- 6.

Statistical processing:

- 7.

Literature search: MDFP, EEH and JSS.

- 8.

Drafting of the article: MDFP, EEH and FJBG.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: MDFP, EEH, FJBG, RRG and JSS.

- 10.

Approval of the final version: MDFP, EEH, FJBG, RRG and JSS.

There has been no source of funding for this manuscript.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Ferrer Puchol MD, Esteban Hernández E, Blanco González FJ, Ramiro Gandia R, Solaz Solaz J, Pacheco Usmayo A. Embolización intraarterial selectiva como tratamiento de la patología hemorroidal. Radiología. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rx.2019.12.004