Difficulties to reach centers that offer primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in a timely manner turn intravenous thrombolysis into the predominant reperfusion mode in patients with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in Brazil. In this scenario, rescue PCI becomes an important therapeutic option for patients who fail reperfusion. We have compared hospital outcomes of these two PCI modalities in STEMI.

MethodsBetween August 2006 to October 2012, consecutive patients with STEMI enrolled in the Angiocardio Registry were submitted to primary or rescue PCI. The incidence of in-hospital major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) was compared.

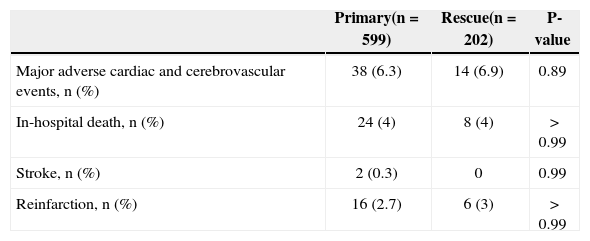

ResultsWe evaluated 801 patients undergoing primary (n=599) or rescue PCI (n=202). In the rescue PCI group a lower frequency of thrombi, total occlusions, pre-procedure TIMI 0/1 flow and angiographically detectable collaterals was observed. The use of stents was similar, as well as the procedure success rates (91.7% vs 90.6%; P=0.75). The incidence of MACCE (6.3% vs 6.9%; P=0.89), death (4% vs 4%; P>0.99), stroke (0.3% vs 0; P=0.99) and reinfarction (2.7% vs 3%; P>0.99) was not different between groups. In the multivariate analysis, the presence of dyslipidemia [odds ratio (OR) 2.190, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) 1.14-4.16; P=0.01], Killip class III or IV (OR 7.494, 95% CI 3.90-14.31; P<0.01) and lesions with moderate/severe calcification (OR 2.852, 95% CI 1.39-5.62; P<0.01), were the variables that best explained in-hospital MACCE.

ConclusionsIn this contemporary registry, rescue and primary PCI had similar in-hospital results.

Desfechos Hospitalares em Pacientes Submetidos aIntervenção Coronária Percutânea Primária versus de Resgate

IntroduçãoDificuldades de acesso em tempo hábil a centros que oferecem intervenção coronária percutânea (ICP) primária fazem com que a trombólise química seja a modalidade de reperfusão predominante em pacientes com infarto comsupradesnivelamento do segmento ST (IAMCSST) no Brasil. Nesse cenário, a ICP de resgate torna-se importante opção para pacientes com insucesso na reperfusão. Comparamos osdesfechos hospitalares dessas duas modalidades de ICP no IAMCSST.

MétodosEntre agosto de 2006 e outubro de 2012, pacientes consecutivos do Registro Angiocardio, com IAMCSST, foram submetidos à ICP primària ou de resgate. Foi comparada a incidencia de eventos cardíacos e cerebrovasculares adversos maiores (ECCAM) hospitalares

ResultadosAvaliamos 801 pacientes submetidos a ICP primària (n=599) ou a ICP de resgate (n=202). No grupo ICP de resgate foi observada menor frequencia de trombos, oclusoes totais, fluxo TIMI 0/1 pré-procedimento e presenga de circulagao colateral. Oemprego de stents foi similar, assim como a taxa de sucesso do procedimento (91,7% vs. 90,6%; P=0,75). A incidencia de ECCAM (6,3% vs. 6,9%; P=0,89), óbito (4% vs. 4%; P>0,99), acidente vascular cerebral (0,3% vs. 0%; P=0,99) e reinfarto (2,7% vs. 3%; P>0,99) nao diferiu entre os grupos. Na análise multivariada, dislipidemia (oddsratio [OR] 2,190; intervalo de confianga de 95% [IC 95%] 1,14-4,16; P=0,01], classe funcional Killip III ou IV (OR: 7,494; IC 95%: 3,90-14,31; P<0,01) e lesoes com calcificagao moderada/ acentuada (OR: 2,852; IC 95%: 1,39-5,62; P<0,01) foram as variáveis que melhor explicaram os ECCAM hospitalares.

ConclusõesNeste registro contemporaneo, a ICP de resgate obteve resultados hospitalares similares aos da ICP primária.

Acute myocardial infarction is an important cause of morbidity and mortality throughout the world. In Brazil, in 2010, over 80,000 deaths were recorded from acute ischemic heart syndromes.1Blood flow return, either by chemical thrombolysis or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), if performed within the first hours of symptom onset, is considered the best strategy for the treatment of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), with proven clinical benefits and reduced mortality, to approximately 4% to 7%.2−4

Primary PCI, despite the evidence of superiority in relation to chemical thrombolysis,5−8 with lower rates of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) and higher rates of patency in the culprit vessel, is not widely available in Brazil. Difficulties to reach hospitals that provide the intervention within a timely manner result in a relatively low number of primary PCIs in this country. It is estimated by the Department of Informatics of the Brazilian Unified Health System (Departamento de Informática do Sistema Único de Saúde - DATASUS) that only 13% to 15% of hospitalized patients with STEMI receive primary PCI as a reperfusion strategy. Although data from the National Cardiovascular Intervention Center (Central Nacional de IntervengSes Cardiovasculares - CENIC) show a progressive increase in primary PCIs between 2006 and 2010, chemical thrombolysis remains the predominant reperfusion modality, used in over 40% of patients with STEMI.9 Rescue PCI is mandatory for patients who fail post-fibrinolytic reperfusion (segment resolution<50% in 60 minutes), as it reduces the incidence of MACCE, when compared with re-thrombolysis or with conservative treatment.10−12

There have been few reports in Brazil comparing primary and rescue PCI strategies, including the publication by Mattos et al.,13 using data from CENIC between 1997 and 2000, which showed a higher in-hospital mortality for rescue PCI in a sample in which the use of coronary stents was restricted to slightly more than half of the studied patients. This study aims at comparing in-hospital outcomes between contemporary primary and rescue PCI in STEMI.

METHODSPatientsThis study included consecutive patients from the Angiocardio registry with STEMI undergoing primary PCI or rescue PCI, from August 2006 to October 2012. This registry includes all patients undergoing PCI in Hospital Bandeirantes, Hospital Rede D'Or Sao Luiz - Unidade Analia Franco, and Hospital Leforte, all located in Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil; in Hospital Vera Hospital Cruz, Campinas, SP, Brazil; and in Hospital Regional Vale do Paraiba, Taubate, SP, Brazil.

The clinical and angiographic characteristics were compared, as well as characteristics related to the procedure, rates of success, and incidence of MACCE at discharge. Data were prospectively collected and stored in a computerized database for further analysis.

Percutaneous coronary interventionThe technique, access route, and choice of material, including the use of thrombus aspiration catheters and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors during the procedure, were at the discretion of the surgeons. Unfractionated heparin was used at a dose of 70 U/kgto 100 U/kg at the beginning of the procedure, except in patients who were already receiving low molecular-weight heparin. In these cases, a dose of 0.3mg/kg was added intravenously, adjusted according to the last dose interval. All patients received combined antiplatelet therapy with acetylsalicylic acid (dose of 100 to 200mg/day) and clopidogrel (loading dose of 300 to 600mg, and maintenance dose of 75mg/day).

Angiographic analysis and definitionsThe analyses were performed on at least two orthogonal projections by professionals who had experience with digital quantitative angiography. This study used the same angiographic criteria as CENIC. The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association criteria were used to identify the type of lesion.4 Lesions were considered long when their length was>20mm. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) classification was used to classify pre-and post-procedure coronary flow.14 The rate of procedural success was defined as attaining angiographic success (residual stenosis<30%, with TIMI 3 flow) and absence of MACCE, comprising death, stroke, reinfarction, and emergency coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery.

Reinfarction was defined by the presence of new ischemic electrocardiographic changes and/or alterations in laboratory markers of myocardial necrosis and/or angiographic evidence of vessel-target occlusion. The overall mortality was considered for the analysis (death from any cause) during the hospitalization period.

Statistical AnalysisThe data were stored in an Oracle-based Coreangio database, plotted on Excel spread sheets, and analyzed using SPSS software, version 15.0. Continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations, and categorical variables as absolute numbers and percentages. The associations between continuous variables were evaluated using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) model. The associations between categorical variables were evaluated by chi-squared test, Fisher's exact test, or likelihood ratio, when appropriate. Significance level was set at P<0.05. Multivariate analysis was used to identify independent predictors of MACCE.

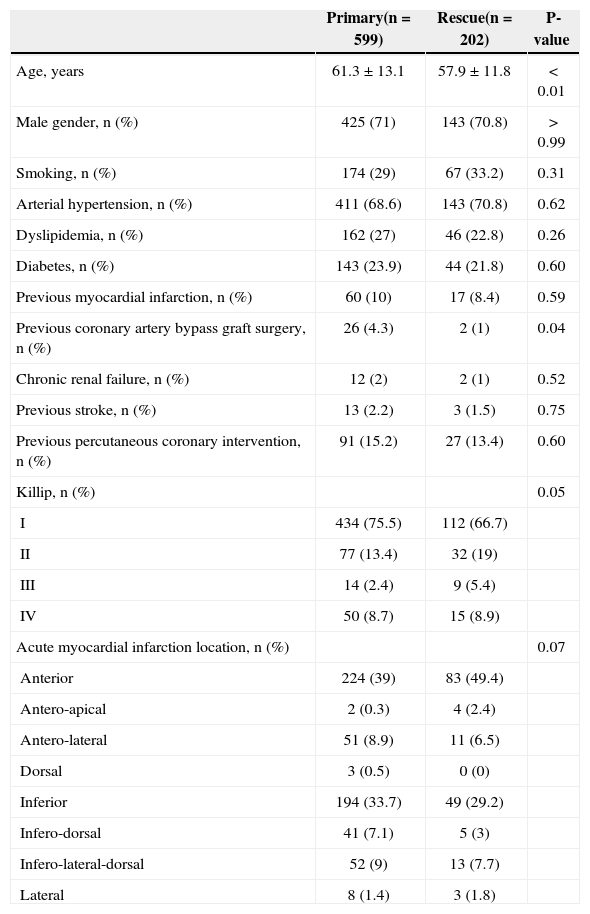

RESULTSThe present study evaluated 801 consecutive patients who underwent primary PCI (n=599 patients; 664 vessels; 719 lesions) or rescue PCI (n=202; patients; 218 vessels; 242 lesions). The rescue PCI group was, on average, three years younger and had a lower incidence of prior revascularization surgery (4.3% vs. 1%; P=0.04). There was a tendency in this group of patients to have more advanced Killip class (P=0.05) and higher incidence of anterior wall myocardial infarction (P=0.07). The groups did not differ regarding the other clinical characteristics (Table 1).

Clinical Characteristics

| Primary(n=599) | Rescue(n=202) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 61.3±13.1 | 57.9±11.8 | < 0.01 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 425 (71) | 143 (70.8) | > 0.99 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 174 (29) | 67 (33.2) | 0.31 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 411 (68.6) | 143 (70.8) | 0.62 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 162 (27) | 46 (22.8) | 0.26 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 143 (23.9) | 44 (21.8) | 0.60 |

| Previous myocardial infarction, n (%) | 60 (10) | 17 (8.4) | 0.59 |

| Previous coronary artery bypass graft surgery, n (%) | 26 (4.3) | 2 (1) | 0.04 |

| Chronic renal failure, n (%) | 12 (2) | 2 (1) | 0.52 |

| Previous stroke, n (%) | 13 (2.2) | 3 (1.5) | 0.75 |

| Previous percutaneous coronary intervention, n (%) | 91 (15.2) | 27 (13.4) | 0.60 |

| Killip, n (%) | 0.05 | ||

| I | 434 (75.5) | 112 (66.7) | |

| II | 77 (13.4) | 32 (19) | |

| III | 14 (2.4) | 9 (5.4) | |

| IV | 50 (8.7) | 15 (8.9) | |

| Acute myocardial infarction location, n (%) | 0.07 | ||

| Anterior | 224 (39) | 83 (49.4) | |

| Antero-apical | 2 (0.3) | 4 (2.4) | |

| Antero-lateral | 51 (8.9) | 11 (6.5) | |

| Dorsal | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Inferior | 194 (33.7) | 49 (29.2) | |

| Infero-dorsal | 41 (7.1) | 5 (3) | |

| Infero-lateral-dorsal | 52 (9) | 13 (7.7) | |

| Lateral | 8 (1.4) | 3 (1.8) |

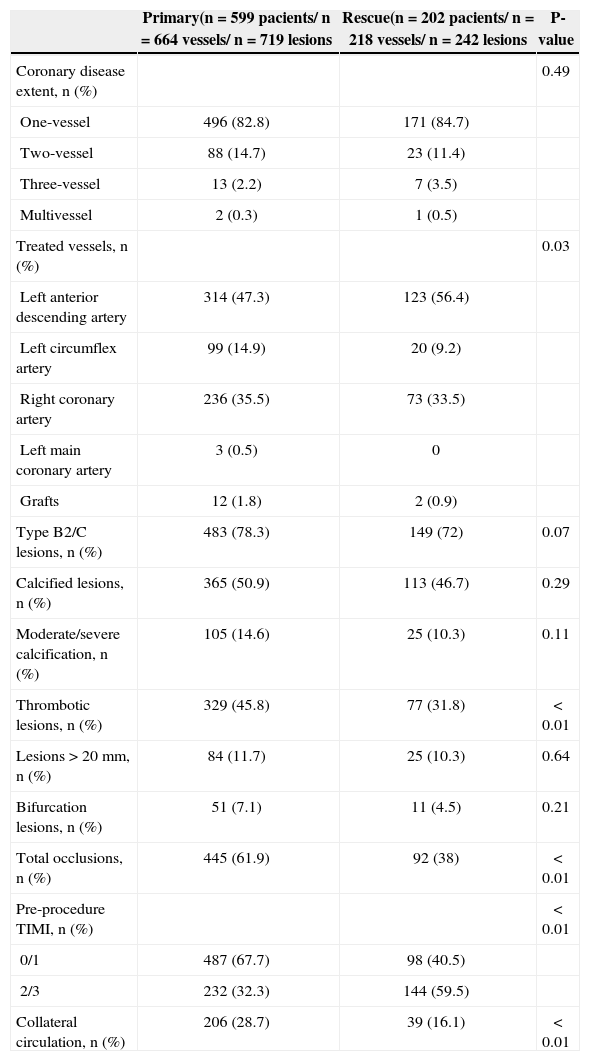

Regarding the angiographic characteristics, a strong predominance of patients with one-vessel involvement (>80%) was observed; the left anterior descending artery was the most often affected vessel, especially in the rescue PCI group (47.3% vs. 56.4%). Lower frequency of lesions with thrombi (45.8% vs. 31.8%; P<0.01); total occlusions (61.9 % vs. 38%; P<0.01); pre-procedure TIMI flow 0/1 (67.7% vs. 40.5%), and the presence of collateral circulation (28.7% vs. 16.1%; P<0.01) was observed in patients undergoing rescue PCI (Table 2).

Angiographic characteristics

| Primary(n=599 pacients/ n=664 vessels/ n=719 lesions | Rescue(n=202 pacients/ n=218 vessels/ n=242 lesions | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coronary disease extent, n (%) | 0.49 | ||

| One-vessel | 496 (82.8) | 171 (84.7) | |

| Two-vessel | 88 (14.7) | 23 (11.4) | |

| Three-vessel | 13 (2.2) | 7 (3.5) | |

| Multivessel | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Treated vessels, n (%) | 0.03 | ||

| Left anterior descending artery | 314 (47.3) | 123 (56.4) | |

| Left circumflex artery | 99 (14.9) | 20 (9.2) | |

| Right coronary artery | 236 (35.5) | 73 (33.5) | |

| Left main coronary artery | 3 (0.5) | 0 | |

| Grafts | 12 (1.8) | 2 (0.9) | |

| Type B2/C lesions, n (%) | 483 (78.3) | 149 (72) | 0.07 |

| Calcified lesions, n (%) | 365 (50.9) | 113 (46.7) | 0.29 |

| Moderate/severe calcification, n (%) | 105 (14.6) | 25 (10.3) | 0.11 |

| Thrombotic lesions, n (%) | 329 (45.8) | 77 (31.8) | < 0.01 |

| Lesions>20mm, n (%) | 84 (11.7) | 25 (10.3) | 0.64 |

| Bifurcation lesions, n (%) | 51 (7.1) | 11 (4.5) | 0.21 |

| Total occlusions, n (%) | 445 (61.9) | 92 (38) | < 0.01 |

| Pre-procedure TIMI, n (%) | < 0.01 | ||

| 0/1 | 487 (67.7) | 98 (40.5) | |

| 2/3 | 232 (32.3) | 144 (59.5) | |

| Collateral circulation, n (%) | 206 (28.7) | 39 (16.1) | < 0.01 |

TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

Regarding the characteristics of the procedures (Table 3), the rates of stent use were similar (83.1% vs. 84.9%, P=0.62), with a low rate of drug-eluting stent (DES) use, especially in the rescue PCI group (7.1% vs. 1.6%; P=0.01). Direct stenting was also more frequent in this group (24.3% vs. 44.3%; P<0.01). Shorter stents were implanted in the rescue PCI group (20.8mm vs. 19.5mm, P=0.01), with no differences between groups regarding stent diameter.

Characteristics of procedures

| Primary(n=599 pacients/ n=664 vessels/ n=719 lesions | Rescue(n=202 pacients/ n=218 vessels/ n=242 lesions | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treated vessels/patient | 1.20±0.48 | 1.20±0.51 | 0.92 |

| Implanted stents, n (%) | 513 (85.6) | 175 (86.6) | 0.81 |

| Stent/patient ratio, n (%) | 1.06±0.62 | 1.00±0.54 | 0.24 |

| Stent use, n (%) | 552 (83.1) | 185 (84.3) | 0.62 |

| Drug-eluting stents, n (%) | 39 (7.1) | 3 (1.6) | 0.01 |

| Direct-stenting technique, n (%) | 134 (24.3) | 82 (44.3) | < 0.01 |

| Stent diameter, mm | 3.09±0.48 | 3.13±0.46 | 0.27 |

| Stent length, mm | 20.8±6.8 | 19.5±6.5 | 0.01 |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, n (%) | 190 (68.3) | 8 (4) | < 0.01 |

| Thromboaspiration, n (%) | 112 (21.8) | 10 (5.7) | < 0.01 |

| Post-procedure TIMI flow, n (%) | 0.18 | ||

| 0/1 | 38 (5.5) | 19 (8.3) | |

| 2/3 | 652 (94.5) | 211 (91.7) | |

| Degree of stenosis, % | |||

| Pre | 95.2±10.4 | 90.7±12.4 | < 0.01 |

| Post | 7.3±22.8 | 9.1±26.4 | 0.36 |

| Procedural success | 549 (91.7) | 183 (90.6) | 0.75 |

A lower degree of pre-procedure lesion stenosis was also observed in this same group (95.2% vs. 90.7%; P<0.01), and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors were used less frequently (68.3% vs. 4%; P<0.01), as well as thrombus aspiration catheters (21.8% vs. 5.7%; P<0.01). The procedure success rates were similar and>90% in both groups.

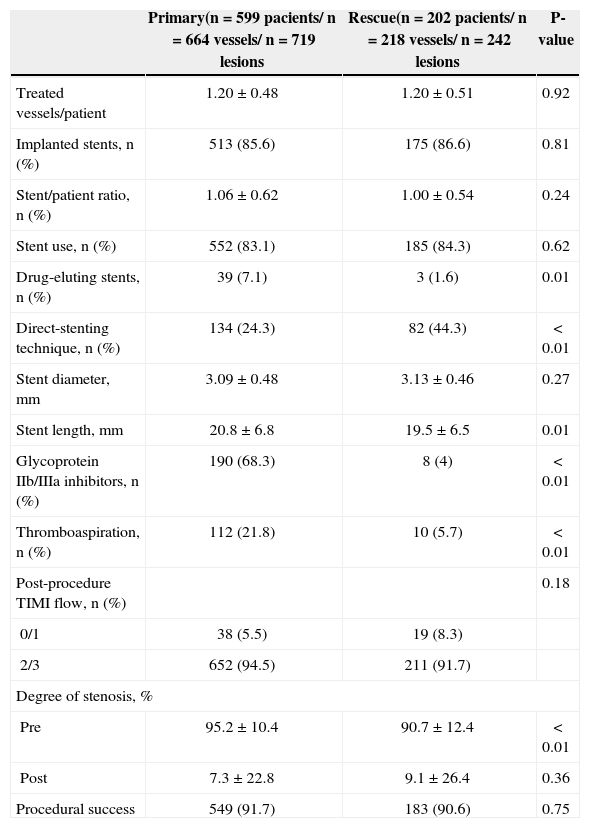

The incidence of MACCE (6.3% vs. 6.9%; P=0.89), in-hospital death (4% vs. 4%; P>0.99), stroke (0.3 % vs. 0; P=0.99), and reinfarction (2.7% vs. 3%; P>0.99) did not differ between the groups. There were no cases of emergency CABG in the sample (Table 4).

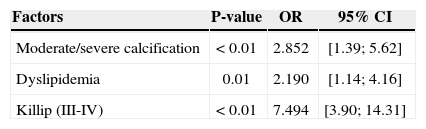

In the univariate analysis, the variables age, smoking, dyslipidemia, presence of lesions with moderate/ severe calcification, prior CABG, chronic renal failure, Killip class III or IV, and use of IIb/IIIa glycoprotein inhibitors showed a significant association with the occurrence of MACCE. In the multivariate analysis, the presence of dyslipidemia (odds ratio [OR], 2.190; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.14 to 4.16; P=0.01], Killip functional class III or IV (OR, 7.494; 95% CI, 3.90 to 14.31; P<0.01), and lesions with moderate/ severe calcification (OR, 2.852; 95% CI, 1.39 to 5.62; P<0.01) were the variables that best explained the presence of in-hospital MACCE (Table 5).

Independent predictors of in-hospital major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events after PCI

| Factors | P-value | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate/severe calcification | < 0.01 | 2.852 | [1.39; 5.62] |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.01 | 2.190 | [1.14; 4.16] |

| Killip (III-IV) | < 0.01 | 7.494 | [3.90; 14.31] |

95% CI, 95% Confidence Interval; OR, odds ratio.

This study compared in-hospital outcomes between contemporary primary and rescue PCI in STEMI. The findings showed that the occurrence of MACCE was low and similar between groups, with an in-hospital mortality rate of 4%. Similar mortality rates have been recently published in the Strategic Reperfusion (With Tenecteplase and Antithrombotic Treatment) Early After Myocardial Infarction (STREAM) study in patients with less than three hours of STEMI symptom onset submitted to primary PCI strategy or to pharmaco invasive strategy with the use of tenecteplase and transfer to PCI (4.4% and 4.6%, respectively).14

Previous reports have demonstrated higher mortality (6% to 8%) in patients undergoing rescue PCI in relation to primary PCI.13,15,16 In Brazil, Mattos et al.,13with data collected from the CENIC registry, evaluated 9,371 patients and also demonstrated higher mortality of rescue PCI compared with primary PCI (7.4% vs. 5.6%; P=0.034). Conversely, Baer et al.17 showed similar results between the two modalities, concluding that the rescue intervention is the mandatory procedure for the treatment of STEMI, when chemical thrombolysis failure occurs. It is noteworthy that these publications showed a low rate of stenting (<60 %) compared to current rates of contemporary PCI. In the present series, the use of stenting in both groups occurred in over 80% patients. Previous studies have shown that stenting (DES and BMS) favourably affects the prognosis of patients with STEMI, promoting TIMI coronary flow improvement, with lower rates of ventricular dysfunction and mortality.18−20

Previous use of fibrinolytics in the rescue PCI group probably explains the lower thrombotic burden of the lesions and lower frequency of catheter use for thrombus aspiration and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, in addition to the decreased use of the direct stenting technique in the present sample. It also explains the higher incidence of TIMI 2/3 before the procedure, which is associated with better prognosis in patients with STEMI.21,22 The Plasminogen-activator - Angioplasty Compatibility Trial (PACT),23 which compared patients who received rt-PA at a dose of 50mg or placebo prior to catheterization, showed a higher rate of patency of the vessel pre-PCI in the group receiving thrombolytic therapy, with increased left ventricular function preservation. The STREAM- 14study also showed higher pre-PCI TIMI 3 flow rates in patients previously submitted to thrombolysis (pharmaco invasive strategy).

Known predictors of failure and worse prognosis of PCI for myocardial infarction, the moderate/severe coronary calcification, and Killip class III or IV, next to a history of dyslipidemia, were the factors that best explained the occurrence of MACCE in this study.2−4,24 Among them, the presence of more advanced Killip functional class raised the risk of MACCE by more than seven-fold.

Rescue PCI, unlike primary PCI, requires further studies to assess its contemporary results; however, in the present registry, it was shown to be a viable alternative for patients that did not have access to primary PCI and those who failed thrombolytic therapy.

Study limitationsLimitations to the present study are the retrospective analysis of data between two cohorts with non-adjusted clinical variables and the absence of late follow-up.

CONCLUSIONSIn this contemporary registry, rescue PCI showed similar results to those of in-hospital primary PCI.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.