Recently, the MOZART study demonstrated that using intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) reduces the volume of contrast used in the procedure. The authors assessed the incidence of late adverse cardiovascular events in these patients.

MethodsPatients at risk for contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) or volume overload were randomized to angiography-guided versus IVUS-guided PCI, and followed-up for a 1-year period.

ResultsEighty-three patients were included in the angiography-guided (n = 42) or IVUS-guided (n = 41) groups, of whom 77.1% were diabetics and 44.6% had creatinine clearance < 60mL/min/1.73m2. Clinical and angiographic characteristics did not differ between the groups. Most had type B2/C lesions (89.8%) and a median of two stents were used (interquartile range: 1.0-2.0 stents). The duration of IVUS-guided PCI was 14minutes longer than the angiography-guided PCI group (p = 0.006). However, the groups did not differ regarding fluoroscopy time or mean image acquisitions per procedure. CIN occurred in 19.0% vs. 7.3% (p = 0.26). During the 1-year follow-up, 12% of patients had a major cardiovascular event, with two deaths (one in each group), and no differences were found between groups.

ConclusionsThe contrast reduction strategy with IVUS-guided PCI in patients at risk for CIN or volume overload was shown to be safe in the short and long term.

Recentemente, o estudo MOZART demonstrou que a utilização do ultrassom intracoronário (USIC) para guiar a intervenção coronariana percutânea (ICP) diminui o volume de contraste utilizado no procedimento. Avaliamos a incidência de eventos adversos cardiovasculares tardios desses pacientes.

MétodosPacientes com risco para nefropatia induzida por contraste (NIC) ou para sobrecarga de volume, e com indicação de ICP, foram randomizados para procedimento guiado pela angiografia ou USIC, e acompanhados por um período de 1 ano.

ResultadosIncluídos 83 pacientes nos grupos ICP guiado por angiografia (n = 42) ou USIC (n = 41), sendo que 77,1% eram diabéticos e 44,6% tinham clearance de creatinina < 60mL/min/1,73m2. As características clínicas e angiográficas não mostraram diferenças entre os grupos. A maioria tinha lesões tipo B2/C (89,8%) e uma mediana de dois stents foram usados (intervalo interquartil: 1,0-2,0 stents). O tempo de procedimento da ICP guiada por USIC foi 14 minutos maior do que no grupo guiado por angiografia (p = 0,006). No entanto, os grupos não diferiram em relação ao tempo de fluoroscopia ou à média de aquisições de imagem por procedimento. A NIC ocorreu em 19,0% vs. 7,3% (p = 0,26). No período de seguimento de 1 ano, 12% dos pacientes apresentaram algum evento cardiovascular maior, sendo dois óbitos (um para cada grupo), e não houve diferenças entre os grupos.

ConclusõesA estratégia de redução de contraste com a ICP guiada pelo ultrassom intravascular, em pacientes com risco para NIC ou sobrecarga de volume, mostrou-se segura a curto e longo prazos.

Contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) is a potential complication of angiographic procedures and is associated with poor clinical prognosis, in both the short and long term.1 Some strategies have been tested to reduce the incidence of CIN; hydration before and after the procedure is considered the most important prophylactic regimen in this scenario.2,3 Interestingly, to date, there have been few prevention strategies aimed at reducing the contrast volume used during angiography procedures.4,5 Additionally, strategies to reduce contrast volume may also be valuable in patients at risk of volume overload.

Recently, the MOZART (Minimizing cOntrast utiliZation With IVUS Guidance in coRonary angioplasTy) randomized study showed that the rational and intensive use of intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), associated with other contrast reduction techniques, significantly reduces the volume of iodized agent in percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI).6,7 For this purpose, the strategy employed in that study prescribed the use of IVUS to replace angiography at different steps of the procedure. However, despite being acutely effective, the effects of this approach on the longer-term clinical results after coronary intervention are not known.

This study presents the 1-year evolution of the MOZART study, aiming at analyzing the impact on the incidence of cardiovascular events of IVUS-guided PCI.

MethodsThe MOZART study methodology has been previously described6 and will be briefly presented here. This is a randomized, controlled, prospective, parallel, single-center study, carried out in accordance with the regulatory rules of the local Human Research Ethics Committee. All patients signed the free and informed consent form prior to the procedure.

The population enrolled in the study consisted of patients referred from cardiology outpatient clinics of the Instituto do Coração do Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo (SP), Brazil, who had an indication for elective coronary PCI and were at risk for renal dysfunction or volume overload, defined by the presence of one or more of the following factors: age > 75 years; diabetes mellitus; creatinine clearance < 60mL/min/1.73m2, single kidney, or previous renal transplantation; heart failure or left ventricular dysfunction (ejection fraction < 45%); cardiogenic shock; or use of intra-aortic balloon pump. Exclusion criteria were defined as unknown renal function; inability to perform IVUS in the target vessel; allergy to contrast medium; or exposure to nephrotoxic agents in the previous 7 days.

All patients were hydrated for 12hours before and 12hours after the procedure with 1mL/kg of 0.9% saline solution, reduced to 0.5mL/kg for patients at risk of volume overload. Patients were randomized to groups in a non-blinded manner through an electronic system using a 1:1 ratio to undergo PCI guided by angiography or PCI guided by IVUS.

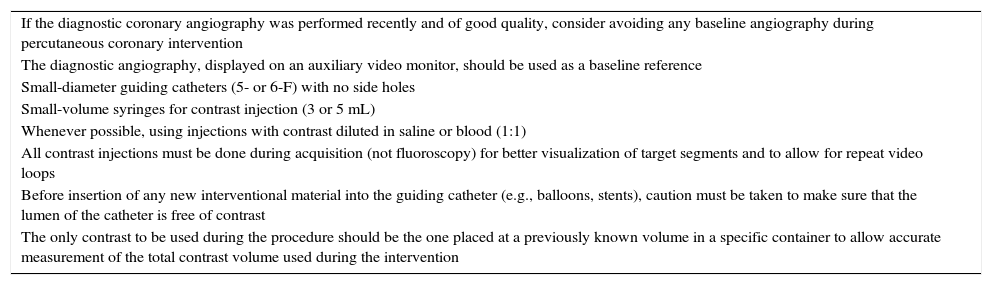

Strategies to reduce the contrast volume were used in both groups (Table 1); moreover, in the group of patients who underwent PCI guided by IVUS, interventionists were encouraged to use IVUS to its maximum potential limit to further reduce the use of contrast agents during the procedure. In this group, IVUS was used throughout the intervention, to guide all the steps of the procedure, substituting the angiography whenever possible. Qualitative and quantitative assessment of the atherosclerotic plaque, the definition of the lesion preparation strategy, the choice of stent diameter and length, and the need for post-dilation and additional stent implantation were guided primarily by IVUS findings. As a final objective of the procedure in this group, the authors expected to achieve optimal stent implantation by implementing the described strategies.

Strategies for contrast volume reduction during percutaneous coronary intervention.

| If the diagnostic coronary angiography was performed recently and of good quality, consider avoiding any baseline angiography during percutaneous coronary intervention |

| The diagnostic angiography, displayed on an auxiliary video monitor, should be used as a baseline reference |

| Small-diameter guiding catheters (5- or 6-F) with no side holes |

| Small-volume syringes for contrast injection (3 or 5 mL) |

| Whenever possible, using injections with contrast diluted in saline or blood (1:1) |

| All contrast injections must be done during acquisition (not fluoroscopy) for better visualization of target segments and to allow for repeat video loops |

| Before insertion of any new interventional material into the guiding catheter (e.g., balloons, stents), caution must be taken to make sure that the lumen of the catheter is free of contrast |

| The only contrast to be used during the procedure should be the one placed at a previously known volume in a specific container to allow accurate measurement of the total contrast volume used during the intervention |

PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

Creatinine clearance was calculated using serum creatinine, through the Cockcroft and Gault equation. Post-PCI CIN was defined as an increase in creatinine > 0.5mg/dL.

The present study evaluated the impact of IVUS-guided PCI on the incidence of cardiovascular events (death, myocardial infarction or target vessel revascularization) 1 year after the procedure. Myocardial infarction was classified as spontaneous, post-PCI or coronary artery bypass graft surgery, or related to stent thrombosis.

Statistical analysisThe final comparative analysis between groups was performed according to the “intention-to-treat” principle.

Categorical variables were described as absolute numbers and proportions and compared using the Chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range (IQ) and compared, respectively, using Student's t test or the Mann-Whitney test. Significance was set at a p-value < 0.05.

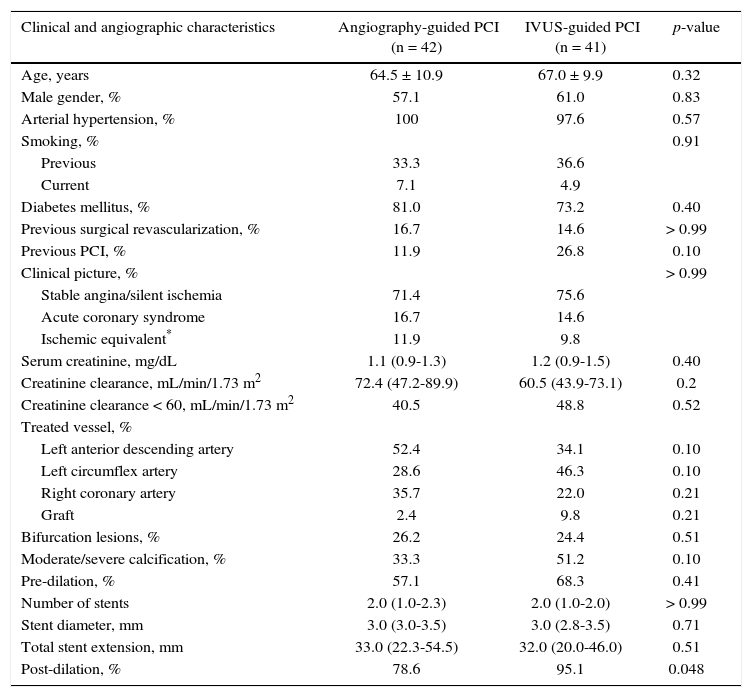

ResultsBetween November 2012 and September 2013, 83 patients were randomized to PCI guided by angiography (n = 42) or IVUS (n = 41). The clinical and angiographic characteristics were similar in both groups (Table 2). The high clinical risk and angiographic complexity of this group is noteworthy, due to the high incidence of diabetic patients (77.1%), most of them with stable coronary disease (73.5%). The serum creatinine of the study population was 1.13mg/dL (IQ: 0.9-1.4mg/dL), and 44.6% had a calculated creatinine clearance of < 60.0mL/min/1.73m2. Most patients had type B2 or C lesions (89.8%) and a median of two stents were used (IQ: 1.0-2.0 stents).

Clinical, angiographic and procedure characteristics.

| Clinical and angiographic characteristics | Angiography-guided PCI (n = 42) | IVUS-guided PCI (n = 41) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 64.5 ± 10.9 | 67.0 ± 9.9 | 0.32 |

| Male gender, % | 57.1 | 61.0 | 0.83 |

| Arterial hypertension, % | 100 | 97.6 | 0.57 |

| Smoking, % | 0.91 | ||

| Previous | 33.3 | 36.6 | |

| Current | 7.1 | 4.9 | |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 81.0 | 73.2 | 0.40 |

| Previous surgical revascularization, % | 16.7 | 14.6 | > 0.99 |

| Previous PCI, % | 11.9 | 26.8 | 0.10 |

| Clinical picture, % | > 0.99 | ||

| Stable angina/silent ischemia | 71.4 | 75.6 | |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 16.7 | 14.6 | |

| Ischemic equivalent* | 11.9 | 9.8 | |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 1.1 (0.9-1.3) | 1.2 (0.9-1.5) | 0.40 |

| Creatinine clearance, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 72.4 (47.2-89.9) | 60.5 (43.9-73.1) | 0.2 |

| Creatinine clearance < 60, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 40.5 | 48.8 | 0.52 |

| Treated vessel, % | |||

| Left anterior descending artery | 52.4 | 34.1 | 0.10 |

| Left circumflex artery | 28.6 | 46.3 | 0.10 |

| Right coronary artery | 35.7 | 22.0 | 0.21 |

| Graft | 2.4 | 9.8 | 0.21 |

| Bifurcation lesions, % | 26.2 | 24.4 | 0.51 |

| Moderate/severe calcification, % | 33.3 | 51.2 | 0.10 |

| Pre-dilation, % | 57.1 | 68.3 | 0.41 |

| Number of stents | 2.0 (1.0-2.3) | 2.0 (1.0-2.0) | > 0.99 |

| Stent diameter, mm | 3.0 (3.0-3.5) | 3.0 (2.8-3.5) | 0.71 |

| Total stent extension, mm | 33.0 (22.3-54.5) | 32.0 (20.0-46.0) | 0.51 |

| Post-dilation, % | 78.6 | 95.1 | 0.048 |

The total contrast volume was 64.5mL (IQ: 42.8-97.0mL), ranging from 19 - 170mL, in the group guided by angiography, vs. 20.0mL (IQ: 12.5-30.0mL), ranging from 3 to 54mL, in the group guided by IVUS (p < 0.001). The contrast volume/creatinine clearance ratio was different between the groups (1.0 [IQ: 0.6-1.9] vs. 0.4 [IQ: 0.2-0.6]; p < 0.001). A low-osmolality contrast was used in all patients, except in one case in the group guided by angiography, which was treated with an iso-osmolar agent.

The duration of PCI procedure guided by IVUS was significantly longer than in the group guided by angiography (34.0minutes [IQ: 18.5-54.5minutes] vs. 48.0minutes [IQ: 34.0-61.0minutes]; p = 0.006). However, the groups did not differ regarding fluoroscopy time (12.2minutes [IQ: 6.8-24.1minutes] vs. 12.2minutes [IQ: 8.4-20.8minutes; p = 0.51) or the mean number of acquisitions per procedure (22.5 [IQ: 16.0-36.3] vs. 25.0 [19.0-32.5]; p = 0.51).

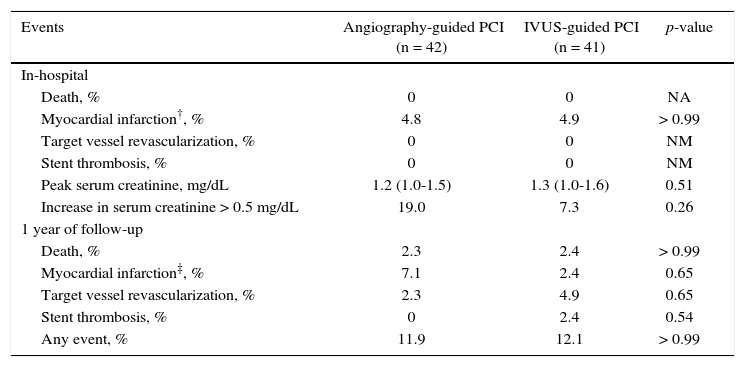

Clinical follow-upThe in-hospital outcomes and those during the first 4 months of follow-up were not different between both groups. The peak serum creatinine in the angiography-guided PCI group was 1.2mg/dL (IQ: 1.0-1.5mg/dL) vs. 1.3mg/dL (IQ: 1.0-1.6mg/dL) in the IVUS-guided PCI group (p = 0.40). CIN occurred in 19.0% in the PCI group guided by angiography and in 7.3% in the PCI group guided by IVUS (p = 0.26).

During the 1-year follow-up, 12% of patients had a major cardiovascular event, with no statistically significant differences between groups, which reflects the safety and the favorable evolution of the initial monitoring phase in this population submitted to IVUS-guided PCI (Table 3).

Clinical follow-up*.

| Events | Angiography-guided PCI (n = 42) | IVUS-guided PCI (n = 41) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital | |||

| Death, % | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Myocardial infarction†, % | 4.8 | 4.9 | > 0.99 |

| Target vessel revascularization, % | 0 | 0 | NM |

| Stent thrombosis, % | 0 | 0 | NM |

| Peak serum creatinine, mg/dL | 1.2 (1.0-1.5) | 1.3 (1.0-1.6) | 0.51 |

| Increase in serum creatinine > 0.5 mg/dL | 19.0 | 7.3 | 0.26 |

| 1 year of follow-up | |||

| Death, % | 2.3 | 2.4 | > 0.99 |

| Myocardial infarction‡, % | 7.1 | 2.4 | 0.65 |

| Target vessel revascularization, % | 2.3 | 4.9 | 0.65 |

| Stent thrombosis, % | 0 | 2.4 | 0.54 |

| Any event, % | 11.9 | 12.1 | > 0.99 |

* Kaplan-Meier estimate; † all after intervention; ‡ all spontaneous. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; IVUS: intravascular ultrasound; NA: not applicable.

The population involved in this study was characterized by having high clinical and angiographic risk for major cardiovascular events. Both groups consisted mainly of diabetic patients, who often have long, calcified, and bifurcated lesions, requiring multiple stents for treatment. Due to the strategy of reducing contrast use in both groups, patients received less volume than the average of 148mL/procedure adopted at the institution for patients with < 60mL/min/1.73 m2. The use of IVUS during PCI allowed a further reduction in contrast volume when compared with the group undergoing PCI guided by angiography. IVUS-guided PCI was shown to be effective and safe; it did not result in higher stent use and did not increase the incidence of adverse events in high-risk patients during the follow-up period.

IVUS-guided PCI lasted 14minutes longer and required more stent post-dilation; nonetheless, the number of stents, stent diameter or length, as well as the fluoroscopy time or the number of image acquisitions showed no differences between the groups. The longer duration of the procedures possibly resulted from the acquisition and interpretation of IVUS images.

This study was not designed to detect clinical efficacy. However, considering the existing evidence supporting the benefits of reducing contrast volume, as well as the demonstration of the short and long-term safety in the contrast volume reduction strategy guided by IVUS, this technique can be used, especially in high-risk groups, as there is an increasing number of patients with coronary atherosclerosis and susceptibility to CIN or volume overload.7

Study limitationsThis study excluded patients whose renal function was not previously known, as well as those who had undergone a recent catheterization or ad hoc procedures. Only patients who had an anatomy favorable to IVUS evaluation were randomized. It is possible that the use of IVUS catheters may have increased the cost of the procedure; conversely, the reduction in contrast volume and possible reduction in the number of complications may favor this approach. Prospective randomized studies in larger populations and dedicated to clinical efficacy are desirable to evaluate the cost-benefits of IVUS use in PCI in patients at risk for CIN or volume overload.

ConclusionsThoughtful and extensive use of IVUS as the primary imaging tool to guide PCI has shown to be safe in the short and long term in patients at risk for contrast-induced nephropathy or volume overload.

FundingThis is an investigational study partially sponsored by the Boston Scientific Corporation.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer review under the responsibility of Sociedade Brasileira de Hemodinâmica e Cardiologia Intervencionista.