Diabetics, especially insulin-treated diabetics, have more extensive coronary atherosclerosis and impaired vascular remodeling. Our objective was to evaluate in-hospital results of contemporaneous percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in a consecutive series of diabetics treated with (ITD) or without (NITD) insulin.

MethodsRetrospective analysis of a multicenter registry with 1,896 diabetics, of which 397 (20.9%) were from the ITD group and 1,499 from the NITD group. Major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) were compared between groups.

ResultsThe ITD group showed a higher rate of women and of patients with chronic renal failure, but showed less complex angiographic characteristics when compared to the NITD group, with fewer B2/C lesions, thrombus-containing lesions, occlusions and TIMI 0/1 flow prior to PCI. We treated 1.4±0.7 vessels/patient with 1.3±0.7 stents/patient in each group and the diameter and length of stents were not different between groups. Clinical in-hospital outcomes showed no differences regarding the occurrence of MACCE (3.8% vs. 2.8%; P=0.40), stroke (0 vs. 0.1%; P > 0.99), myocardial infarction (2.5% vs. 2.1%; P=0.72), emergency cardiovascular bypass graft surgery (0 vs. 0.1%; P > 0.99) or death (1.5% vs. 0.8%; P=0.24). Independent predictors of MACCE in diabetics were the female gender, patients with multivessel disease and TIMI 0/1 flow prior to PCI.

ConclusionsIn our study, ITD was not an independent predictor of in-hospital MACCE.

Intervenção Coronária Percutâneaem Diabéticos Tratados com Insulina

IntroduçãoDiabéticos, especialmente os tratados com insulina, apresentam aterosclerose coronária mais extensa e remodelamento vascular comprometido. Nosso objetivo foi avaliar os resultados hospitalares contemporâneos da intervenção coronária percutânea (ICP) em série consecutiva de diabéticos tratados com (DMI) ou sem (DMNI) insulina.

MétodosAnálise retrospectiva de um registro multicêntrico com 1.896 diabéticos, dos quais 397 (20,9%) eram do grupo DMI e 1.499, do grupo DMNI. Comparamos os eventos cardíacos e cerebrovasculares adversos maiores (ECCAM) entre os dois grupos.

ResultadosO grupo DMI mostrou maior proporção de mulheres e de portadores de insuficiência renal crônica, mas apresentou características de menor complexidade angiográfica, quando comparado ao grupo DMNI, com menor número de lesões tipo B2/C e presença de trombo, oclusões e lesões com fluxo TIMI 0/1 pré-ICP. Foi tratado 1,4±0,7 vaso/paciente com 1,3±0,7 stent/paciente em cada grupo, e o diâmetro e a extensão dos stents não diferiram entre os grupos. Os desfechos clínicos hospitalares não mostraram diferença quanto à ocorrência de ECCAM (3,8% vs. 2,8%; P=0,40), acidente vascular cerebral (0 vs. 0,1%; P > 0,99), infarto do miocárdio (2,5% vs. 2,1%; P=0,72), cirurgia de revascularização miocárdica de emergência (0 vs. 0,1%; P > 0,99) ou óbito (1,5% vs. 0,8%; P=0,24). Foram preditores independentes de ECCAM, em diabéticos, sexo feminino, pacientes com doença multiarterial e fluxo TIMI 0/1 pré-ICP.

ConclusõesEm nosso estudo, o DMI não foi preditor inde pendente de ECCAM hospitalares.

Data from the Framingham study demonstrated that the incidence of type 2 diabetes has doubled in the last 30 years.1 It is estimated that the total number of diabetics worldwide will increase from 171 million in 2000 to 366 million in 2030.2 Brazil follows the same worldwide trend, and is among the ten countries with the highest absolute number of individuals with diabetes.3,4

Type 2 diabetes is a progressive disease, in which peripheral insulin resistance precedes the progressive loss of insulin secretion capacity.3 Thus, the complexity of the pharmacological treatment of this disease is closely related with disease progression, as observed in the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS), in which 50% of the patients originally treated with only one drug required a second drug after three years, and after nine years, 75% were using multiple drugs, including insulin, to achieve the therapeutic goal (HbAC1 < 7.5).5

Diabetics, especially those treated with insulin, show more extensive atherosclerosis and compromised compensatory vascular remodelling. Nicholls et al.6 conducted a systematic review of five studies that used intravascular ultrasound, and demonstrated that, in diabetics, the atheroma volume was larger and the lumen volume was smaller for the same volume of external elastic lamina when compared to non-diabetics. Moreover, insulin-treated patients showed lower amounts of external elastic lamina and lumen for the same volume of atheroma.

Due to the characteristics of higher complexity of coronary damage in diabetic patients, especially those treated with insulin, and the lack of studies in Brazil evaluating this population, this study analyzed, in a large multicenter registry, the in-hospital outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in diabetic patients treated (ITD) or not (NITD) with insulin.

METHODSPopulationFrom August 2006 to October 2012, 6,288 consecutive patients underwent PCI at the centers that constitute the Angiocardio Registry (Hospital Bandeirantes – São Paulo, SP, Brazil; Rede D’Or Hospital São Luiz Analia Franco – São Paulo, SP, Brazil; Hospital Vera Cruz – Campinas, SP, Brazil; Hospital Regional do Vale do Paraíba – Taubaté, SP, Brazil; and Hospital Leforte – São Paulo, SP, Brazil), of whom 1,896 (30.2%) had diabetes mellitus. Data were collected prospectively and stored in a computer database available via internet at all centers participating in the registry.

The primary objective was to compare rates of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (MACCE), including death, stroke, periprocedural infarction, and emergency coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery between the ITD and NITD groups. These outcomes were recorded at the time of hospital discharge.

Percutaneous coronary interventionPCIs were almost entirely performed by femoral access; the radial approach was used as an option in a few cases. The choice of technique and material used during the procedure was at the discretion of the surgeons, as well as the need for glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. Unfractionated heparin was used in the beginning of the procedure at a dose of 70 to 100 U/kg, except in patients who were already using low molecular-weight heparin.

All patients received antiplatelet therapy in combination with acetylsalicylic acid at loading dose of 300mg and maintenance dose of 100mg/day to 200mg/day, and clopidogrel at loading dose of 300mg or 600mg and maintenance dose of 75mg/day. Femoral sheaths were removed four hours after the start of heparin. Radial sheaths were removed immediately after the procedure.

Angiographic analysisAnalyses were performed in at least two orthogonal views by experienced professionals using digital quantitative angiography. This study used the same angiographic criteria contained in the database of the National Centre for Cardiovascular Interventions (Central Nacional de Intervenções Cardiovasculares – CENIC) of the Brazilian Society of Hemodynamics and Interventional Cardiology.7 The type of lesion was classified according to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) criteria.8 The Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) classification was used for the determination of pre- and post-procedure coronary flow.9

DefinitionsProcedural success was defined as achievement of angiographic success (residual stenosis < 30% with TIMI 3 flow), without the occurrence of death, periprocedural infarction, oremergency CABG.

Deaths from any cause were recorded. Myocardial infarction was defined by the reappearance of angina symptoms with electrocardiographic alterations (new ST-segment elevation or new Q waves) and/or angiographic evidence of target-vessel occlusion. Emergency CABG was considered when indicated by procedural failure or complication of the index procedure.

Statistical analysisThe data stored in the Coreangio Oracle-based database were plotted in Excel spreadsheets and analysed using SPSS version 15.0. Continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations, and categorical variables were expressed as absolute numbers and percentages. Associations between continuous variables were assessed using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) model. Associations between categorical variables were evaluated by chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test or likelihood ratio, when appropriate. The significance level was set at P < 0.05. Multivariate analysis was used to identify independent predictors of MACCE.

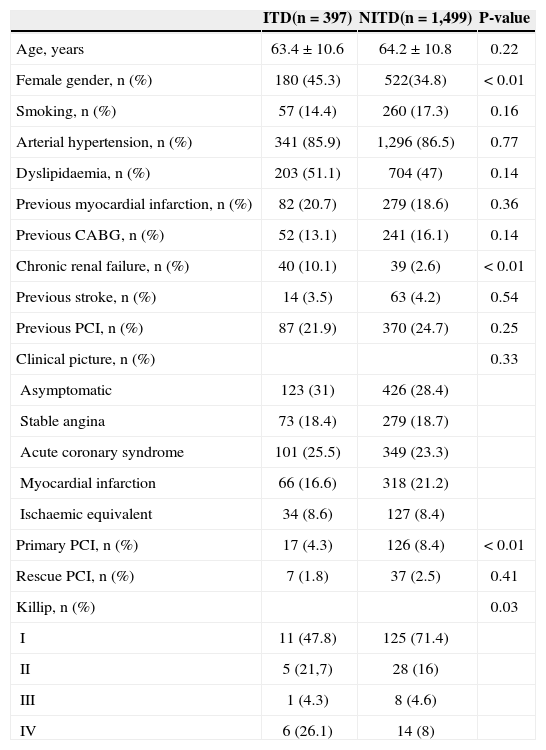

RESULTSOf 1,896 consecutive diabetic patients undergoing PCI, 397 (20.9%) were using insulin (ITD group) and 1,499 (79.1%) were not (NITD). The mean age of both groups was similar (63.4±10.6years vs. 64.2±10.8years; P=0.22), but the ITD group had a higher proportion of female patients (45.3% vs. 34.8; P < 0.01). The prevalence of comorbidities was not different between the groups, except for chronic renal failure, which was more frequent in the ITD group (10.1% vs. 2.6%; P < 0.01). The ITD group was submitted to fewer primary PCIs (4.3% vs. 8.4%; P < 0.01), performed under more adverse clinical conditions (Killip IV) (Table 1).

Clinical characteristics

| ITD(n=397) | NITD(n=1,499) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 63.4±10.6 | 64.2±10.8 | 0.22 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 180 (45.3) | 522(34.8) | < 0.01 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 57 (14.4) | 260 (17.3) | 0.16 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 341 (85.9) | 1,296 (86.5) | 0.77 |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 203 (51.1) | 704 (47) | 0.14 |

| Previous myocardial infarction, n (%) | 82 (20.7) | 279 (18.6) | 0.36 |

| Previous CABG, n (%) | 52 (13.1) | 241 (16.1) | 0.14 |

| Chronic renal failure, n (%) | 40 (10.1) | 39 (2.6) | < 0.01 |

| Previous stroke, n (%) | 14 (3.5) | 63 (4.2) | 0.54 |

| Previous PCI, n (%) | 87 (21.9) | 370 (24.7) | 0.25 |

| Clinical picture, n (%) | 0.33 | ||

| Asymptomatic | 123 (31) | 426 (28.4) | |

| Stable angina | 73 (18.4) | 279 (18.7) | |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 101 (25.5) | 349 (23.3) | |

| Myocardial infarction | 66 (16.6) | 318 (21.2) | |

| Ischaemic equivalent | 34 (8.6) | 127 (8.4) | |

| Primary PCI, n (%) | 17 (4.3) | 126 (8.4) | < 0.01 |

| Rescue PCI, n (%) | 7 (1.8) | 37 (2.5) | 0.41 |

| Killip, n (%) | 0.03 | ||

| I | 11 (47.8) | 125 (71.4) | |

| II | 5 (21,7) | 28 (16) | |

| III | 1 (4.3) | 8 (4.6) | |

| IV | 6 (26.1) | 14 (8) |

ITD, insulin-treated diabetics; NITD, non-insulin treated diabetics; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

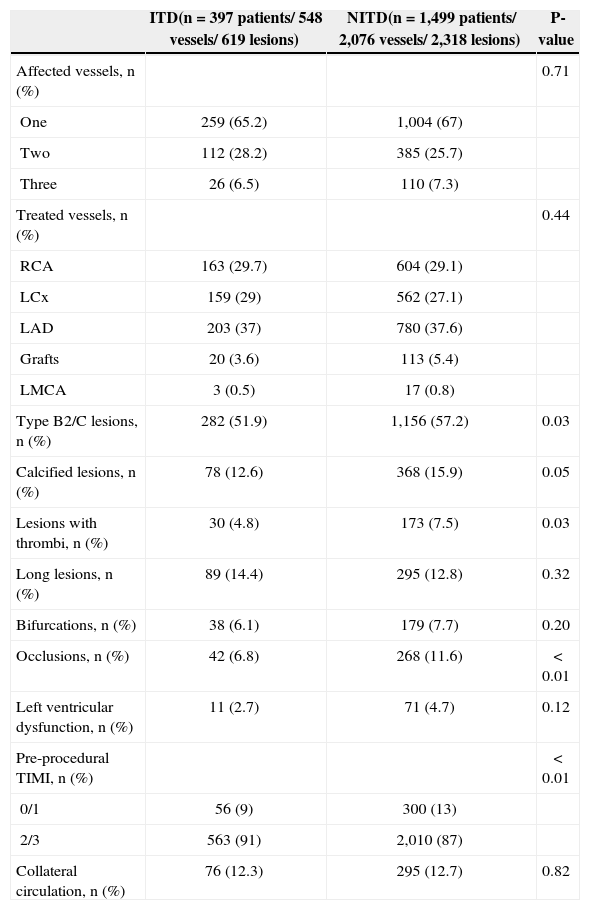

Approximately two-thirds of patients in both groups had single-vessel involvement; the left anterior descending artery was the most frequently treated vessel and left ventricular function was preserved in most patients (Table 2). Patients in the ITD group had some characteristics of less complex treated lesions, with fewer lesions of type B2/C (51.9% vs. 57.2%; P=0.03), thrombus (4.8% vs. 7.5%; P=0.03), occlusions (6.8% vs. 11.6%; P < 0.01), and TIMI flow grade 0/1 pre-PCI (9 % vs. 13%; P < 0.01).

Angiographic characteristics

| ITD(n=397 patients/ 548 vessels/ 619 lesions) | NITD(n=1,499 patients/ 2,076 vessels/ 2,318 lesions) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affected vessels, n (%) | 0.71 | ||

| One | 259 (65.2) | 1,004 (67) | |

| Two | 112 (28.2) | 385 (25.7) | |

| Three | 26 (6.5) | 110 (7.3) | |

| Treated vessels, n (%) | 0.44 | ||

| RCA | 163 (29.7) | 604 (29.1) | |

| LCx | 159 (29) | 562 (27.1) | |

| LAD | 203 (37) | 780 (37.6) | |

| Grafts | 20 (3.6) | 113 (5.4) | |

| LMCA | 3 (0.5) | 17 (0.8) | |

| Type B2/C lesions, n (%) | 282 (51.9) | 1,156 (57.2) | 0.03 |

| Calcified lesions, n (%) | 78 (12.6) | 368 (15.9) | 0.05 |

| Lesions with thrombi, n (%) | 30 (4.8) | 173 (7.5) | 0.03 |

| Long lesions, n (%) | 89 (14.4) | 295 (12.8) | 0.32 |

| Bifurcations, n (%) | 38 (6.1) | 179 (7.7) | 0.20 |

| Occlusions, n (%) | 42 (6.8) | 268 (11.6) | < 0.01 |

| Left ventricular dysfunction, n (%) | 11 (2.7) | 71 (4.7) | 0.12 |

| Pre-procedural TIMI, n (%) | < 0.01 | ||

| 0/1 | 56 (9) | 300 (13) | |

| 2/3 | 563 (91) | 2,010 (87) | |

| Collateral circulation, n (%) | 76 (12.3) | 295 (12.7) | 0.82 |

ITD, insulin-treated diabetics; NITD, non-insulin treated diabetics; RCA, right coronary artery; LCx, left circumflex artery; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LMCA, left main coronary artery; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

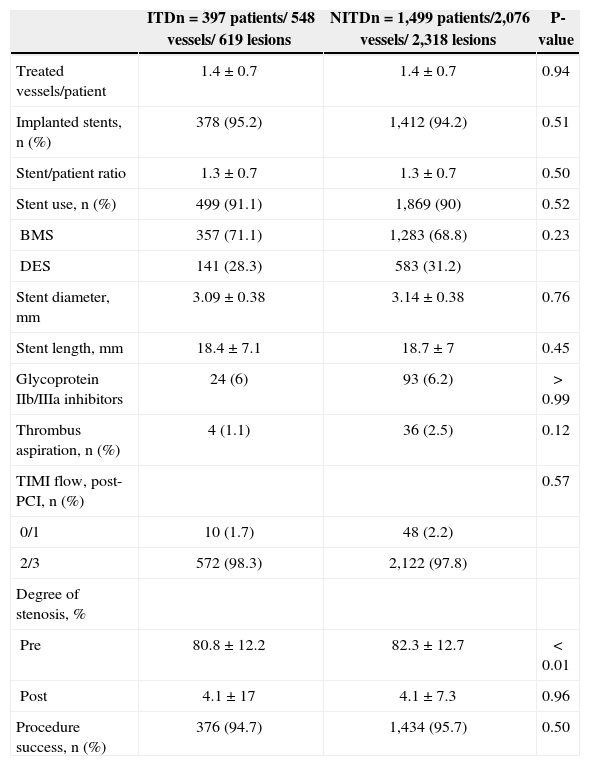

Data on the procedures are shown in Table 3. A total of 1.4±0.7 vessels/patient were treated, with 1.3±0.7 stents/patient in both groups. Less than a third of the population received drug-eluting stents (28.3% vs. 31.2%; P=0.23). The diameter (3.09±0.38mm vs. 3.14±0.38mm; P=0.76) and length (18.4±7.1mm vs. 18.7±7mm; P=0.45) of stents did not differ between groups. Procedural success was high and similar between ITD and NITD groups (94.7% vs. 95.7%, respectively; P=0.50).

Characteristics of procedures

| ITDn=397 patients/ 548 vessels/ 619 lesions | NITDn=1,499 patients/2,076 vessels/ 2,318 lesions | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treated vessels/patient | 1.4±0.7 | 1.4±0.7 | 0.94 |

| Implanted stents, n (%) | 378 (95.2) | 1,412 (94.2) | 0.51 |

| Stent/patient ratio | 1.3±0.7 | 1.3±0.7 | 0.50 |

| Stent use, n (%) | 499 (91.1) | 1,869 (90) | 0.52 |

| BMS | 357 (71.1) | 1,283 (68.8) | 0.23 |

| DES | 141 (28.3) | 583 (31.2) | |

| Stent diameter, mm | 3.09±0.38 | 3.14±0.38 | 0.76 |

| Stent length, mm | 18.4±7.1 | 18.7±7 | 0.45 |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors | 24 (6) | 93 (6.2) | > 0.99 |

| Thrombus aspiration, n (%) | 4 (1.1) | 36 (2.5) | 0.12 |

| TIMI flow, post-PCI, n (%) | 0.57 | ||

| 0/1 | 10 (1.7) | 48 (2.2) | |

| 2/3 | 572 (98.3) | 2,122 (97.8) | |

| Degree of stenosis, % | |||

| Pre | 80.8±12.2 | 82.3±12.7 | < 0.01 |

| Post | 4.1±17 | 4.1±7.3 | 0.96 |

| Procedure success, n (%) | 376 (94.7) | 1,434 (95.7) | 0.50 |

ITD, insulin-treated diabetics; NITD, non-insulin-treated diabetics; BMS, bare metal stents; DES, drug-eluting stents; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

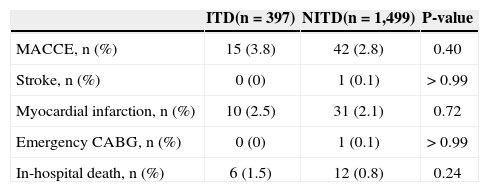

The in-hospital clinical outcomes (Table 4) showed no difference in the occurrence of MACCE (3.8% vs. 2.8%; P=0.40), stroke (0% vs. 0.1%; P > 0.99), myocardial infarction (2.5% vs. 2.1%; P=0.72), emergency coronary artery bypass grafting (0% vs. 0.1%; P > 0.99) or death (1.5% vs. 0.8%; P=0.24).

In-hospital clinical outcomes

| ITD(n=397) | NITD(n=1,499) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACCE, n (%) | 15 (3.8) | 42 (2.8) | 0.40 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | > 0.99 |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 10 (2.5) | 31 (2.1) | 0.72 |

| Emergency CABG, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | > 0.99 |

| In-hospital death, n (%) | 6 (1.5) | 12 (0.8) | 0.24 |

ITD, insulin-treated diabetics; NITD, non-insulin treated diabetics; MACCE, major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

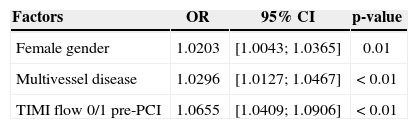

In the univariate analysis, the variables female gender, multivessel disease, lesions with thrombus, TIMI flow 0/1 pre-PCI, presence of collateral circulation, primary PCI, rescue PCI, and adjunctive use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors showed a significant association with MACCE occurrence. In the multivariate analysis, female gender (odds ratio [OR], 1.0203; 95% confidence interval [95% CI]=1.0043-1.00365; P=0.01), multivessel disease (OR, 1.0296; 95% CI, 1.0127-1.0467; P < 0.01), and TIMI flow 0/1 pre-PCI (OR, 1.0655; 95% CI, 1.0409 to 1.0906; P < 0.01) were the variables that best explained the presence of in-hospital MACCE (Table 5).

Independent predictors of in-hospital major cardiac and cerebrovascular events in diabetic patients

| Factors | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 1.0203 | [1.0043; 1.0365] | 0.01 |

| Multivessel disease | 1.0296 | [1.0127; 1.0467] | < 0.01 |

| TIMI flow 0/1 pre-PCI | 1.0655 | [1.0409; 1.0906] | < 0.01 |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

Diabetics treated with PCI included in the present study are representative of the national clinical practice, with a predominance of patients with stable single vessel coronary artery disease and preserved ventricular function, mostly treated with bare-metal stents.10 Insulintreated diabetics, who comprised approximately one-fifth of the population, had greater clinical complexity than other patients, but lower angiographic complexity. This discrepancy is possibly explained by selection bias, in which patients with more complex anatomy are more likely to be referred for CABG.11

The number of treated vessels and the number of stents per patient corroborate the finding that angiographically less complex patients are referred for PCI. The limited availability of drug-eluting stents in this population reinforces these findings, which logically causes interventionists to treat patients with a lower number of involved vessels and less complex lesions. Although slightly over 50% of the lesions were type B2/C, the prevalence of more challenging angiographic characteristics, such as bifurcations and occlusions was low, resulting in high procedural success, which was similar between groups.

The use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors during PCI in diabetic patients has been recommended in the past decade by studies that demonstrated reduced major adverse cardiac events rates.12 However, due to the effectiveness and safety of pre-treatment with clopidogrel, and to the availability of new antiplatelet treatment associated with acetylsalicylic acid in the dual antiplatelet regimen, the current use of glycoprotein IIb/ IIIa has been restricted to patients with acute coronary syndrome with large thrombotic burden, or as rescue therapy in vessel occlusion during the procedure.13 This evidence justifies the low use of this drug in the present registry.

The in-hospital clinical outcomes were similar between groups, and were consistent with a study that also evaluated acute events in diabetic patients treated or not treated with insulin.14 In fact, in a recently developed model with 588,398 procedures from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry15 to predict inhospital mortality, cardiogenic shock was the strongest predictor, followed by renal failure and age. Diabetes was not included in this eight-variable model.

Diabetes mellitus is a marker of poor prognosis in the medium- and long-term of post-PCI with higher incidence of angiographic and clinical events, especially coronary restenosis; the use of drug-eluting stents is recommended (class 1 indication, level of evidence A) to obtain best results.13 The subgroup analysis of the Drug-Eluting Stent in the Real World (DESIRE) registry, which assessed the late outcome after PCI with drug-eluting stents in diabetic and non-diabetic patients, confirmed these findings in Brazil.16 In the present registry, drug-eluting stents were used in approximately one-third of the patients; this rate was not higher because the Brazilian Unified Health System does not yet provide these devices.

Study LimitationThe limitations of this study were the retrospective analysis of data and the absence of late follow-up.

ConclusionIn the present study, ITD was not an independent predictor of hospital MACCE.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTSThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.