The number of elderly patients submitted to primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is increasingly prevalent. Historically, this population has a worse prognosis when compared to the younger ones. This study aimed to compare the characteristics and 30-day clinical outcomes of patients aged ≥ 80 years to those < 80 years submitted to primary PCI.

MethodsObservational, prospective cohort study, extracted from the database of Instituto de Cardiologia do Rio Grande do Sul, between 2009 and 2013.

ResultsA total of 1,970 patients were included, of whom 122 (6.2%) were aged ≥ 80 years. The elderly showed a predominance of the female gender (50% vs. 29%; p < 0.001), diabetes (34.4% vs. 23.2%; p = 0.004), Killip class 3 or 4 (13.1% vs. 7.4%; p < 0.02), and longer door-to-balloon time (1.4 hour [1.0-1.9 hour] vs. 1.1 hour [0.8-1.5 hour]; p < 0.001). The TIMI 3 post flow did not show any difference between the groups (86% vs. 90.7%; p = 0.08), but the Blush 3 post was lower (59.3% vs. 70.9%; p = 0.01) in the elderly. Angiographic success was obtained in 92.0% vs. 95.6%; p = 0.07. Temporary pacemakers, severe arrhythmias, and aborted sudden death were more frequently observed in patients aged ≥ 80 years. The rates of major adverse cardiovascular events and death at 30 days were higher in the older group (32.2% vs. 11.5% and 29.7% vs. 7.2%; p < 0.001).

ConclusionsIn this contemporary analysis, patients aged ≥ 80 years undergoing primary PCI had a more severe clinical and angiographic profile, longer door-to-balloon time, lower final Blush 3, with higher rates of hospital complications and 30-day mortality when compared with younger patients.

É cada vez mais prevalente o número de idosos submetidos à intervenção coronariana percutânea primária (ICPp). Historicamente, essa população apresenta pior prognóstico quando comparada aos mais jovens. Nosso objetivo foi comparar as características e os desfechos clínicos em 30 dias de pacientes ≥ 80 anos aos < 80 anos submetidos à ICPp.

MétodosEstudo de coorte observacional, prospectivo, extraído do banco de dados do Instituto de Cardiologia do Rio Grande do Sul, entre 2009 e 2013.

ResultadosForam incluídos 1.970 pacientes, sendo 122 (6,2%) com idade ≥ 80 anos. Os mais idosos mostraram predomínio do sexo feminino (50% vs. 29%; p < 0,001), diabetes (34,4% vs. 23,2%; p = 0,004), classe Killip 3 ou 4 (13,1% vs. 7,4%; p = 0,02) e tempo porta-balão superior (1,4 hora [1,0-1,9 hora] vs. 1,1 hora [0,8-1,5 hora]; p < 0,001). O fluxo TIMI 3 pós não mostrou diferença entre os grupos (86% vs. 90,7%; p = 0,08), mas o Blush 3 pós foi menor (59,3% vs. 70,9%; p = 0,01) nos idosos. O sucesso angiográfico foi obtido em 92,0% vs. 95,6%; p = 0,07. Necessidade de marca-passo provisório, arritmias graves e morte súbita abortada foram mais frequentes nos pacientes ≥ 80 anos. Taxas de eventos cardiovasculares adversos maiores e óbito em 30 dias foram mais frequentes no grupo mais idoso (32,2% vs. 11,5% e 29,7% vs. 7,2%; p < 0,001).

ConclusõesNesta análise contemporânea, pacientes ≥ 80 anos submetidos à ICPp apresentaram perfil clínico e angiográfico mais grave, tempo porta-balão mais prolongado, menor Blush 3 final, com maiores taxas de complicações hospitalares e mortalidade em 30 dias, quando comparados aos pacientes mais jovens.

The strategy of mechanical recanalization has been preferred to the use of thrombolytics, especially in the elderly subgroup, as they have increased bleeding rates. Registries of patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) treated with mechanical recanalization show an increasing number of patients who are elderly or aged ≥ 80 years.1,2

This subgroup may have an atypical presentation, including silent or unrecognized AMI, or left bundle branch block (LBBB) as an electrocardiographic presentation.3 Additionally, cognitive problems may delay the identification of the clinical picture.

Patients older than 80 years have a two- to three-fold increased risk of cardiogenic shock, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation during hospitalization.4 Killip class ≥ 2 and acute heart failure are much more common in patients aged ≥ 85 years.4,5 The in-hospital mortality of octogenarians is three-fold higher and, in nonagenarians, four-fold higher than in younger patients with ST-segment elevation AMI (STEMI).4

This study aimed to increase the known evidence, contributing to a national database, as the evidence for this age group is scarce, as elderly patients are usually excluded from the large clinical trials. The data is limited to observational studies, which hinders the assessment of the results of procedures and drug therapy applied to them.3,6

Thus, the objective of this study was to compare the clinical, angiographic, and procedure characteristics, as well as clinical outcomes of patients with STEMI aged ≥ 80 years with those aged < 80 years, submitted to primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) at this institution.

MethodsThis was a single-center, prospective cohort study that included all patients with STEMI submitted to primary PCI at Instituto de Cardiologia do Rio Grande do Sul, from December 2009 to December 2013. All enrolled patients signed the Informed Consent Form, and the study was approved by the institution's Ethics Committee.

PopulationSequential patients with STEMI admitted to this institution and referred to primary PCI were considered for inclusion in the study. STEMI was defined as chest pain at rest lasting more than 30minutes associated with ST-segment elevation > 1mm in two or more contiguous leads of the electrocardiogram, or new LBBB. Exclusion criteria were chest pain lasting more than 12hours and patient refusal to participate in the study.

The primary PCI was performed as recommended in the literature.7 All patients were medicated on admission with 300mg of acetylsalicylic acid and 300 to 600mg of clopidogrel, 60mg of prasugrel, or 180mg of ticagrelor. Unfractionated heparin (60 to 100 U/kg) was administered prior to the primary PCI. Technical aspects of the procedure, such as type and number of stents, use of adjunctive devices, and use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors were at the discretion of the interventionist responsible for the primary PCI.

Blood collection for laboratory analysis was performed in the emergency room prior to referral to the primary PCI.

Statistical analysisQualitative variables were described as absolute and relative frequencies, and compared with the Chi-squared test. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and compared with the unpaired Student's t test. Continuous variables with non-normal distribution were shown as median and interquartile range, and compared with the Mann-Whitney test.

The data were collected in a Microsoft Access database, and statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows, version 17.0. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed p-value ≤ 0.05.

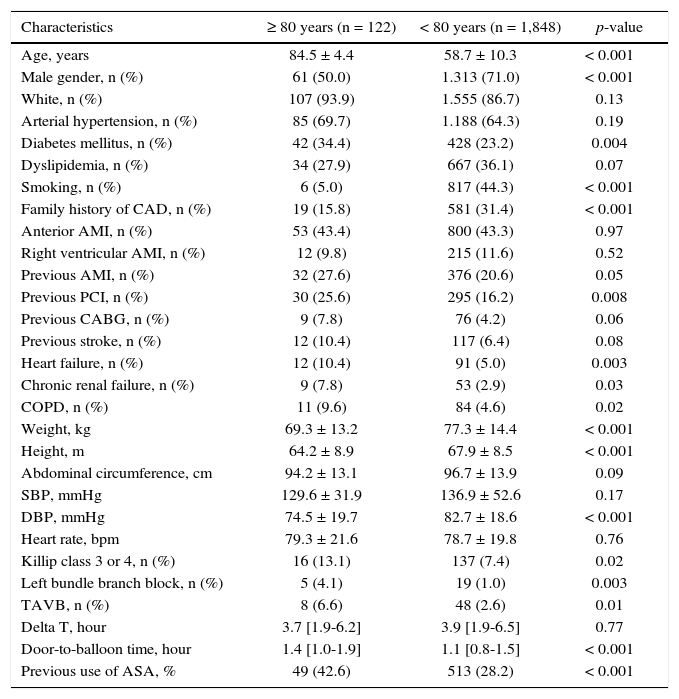

ResultsA total of 1,970 consecutive patients with STEMI were included, of whom 122 (6.2%) were aged ≥ 80 years. The mean age was 84.5 ± 4.4 years and 58.7 ± 10.3 years; the elderly showed a predominance of the female gender (50% vs. 29%; p < 0.001), diabetes (34.4% vs. 23.2%; p = 0.004); conditions such as renal failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, in addition to a lower number of smokers (Table 1).

Baseline clinical characteristics.

| Characteristics | ≥ 80 years (n = 122) | < 80 years (n = 1,848) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 84.5 ± 4.4 | 58.7 ± 10.3 | < 0.001 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 61 (50.0) | 1.313 (71.0) | < 0.001 |

| White, n (%) | 107 (93.9) | 1.555 (86.7) | 0.13 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 85 (69.7) | 1.188 (64.3) | 0.19 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 42 (34.4) | 428 (23.2) | 0.004 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 34 (27.9) | 667 (36.1) | 0.07 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 6 (5.0) | 817 (44.3) | < 0.001 |

| Family history of CAD, n (%) | 19 (15.8) | 581 (31.4) | < 0.001 |

| Anterior AMI, n (%) | 53 (43.4) | 800 (43.3) | 0.97 |

| Right ventricular AMI, n (%) | 12 (9.8) | 215 (11.6) | 0.52 |

| Previous AMI, n (%) | 32 (27.6) | 376 (20.6) | 0.05 |

| Previous PCI, n (%) | 30 (25.6) | 295 (16.2) | 0.008 |

| Previous CABG, n (%) | 9 (7.8) | 76 (4.2) | 0.06 |

| Previous stroke, n (%) | 12 (10.4) | 117 (6.4) | 0.08 |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 12 (10.4) | 91 (5.0) | 0.003 |

| Chronic renal failure, n (%) | 9 (7.8) | 53 (2.9) | 0.03 |

| COPD, n (%) | 11 (9.6) | 84 (4.6) | 0.02 |

| Weight, kg | 69.3 ± 13.2 | 77.3 ± 14.4 | < 0.001 |

| Height, m | 64.2 ± 8.9 | 67.9 ± 8.5 | < 0.001 |

| Abdominal circumference, cm | 94.2 ± 13.1 | 96.7 ± 13.9 | 0.09 |

| SBP, mmHg | 129.6 ± 31.9 | 136.9 ± 52.6 | 0.17 |

| DBP, mmHg | 74.5 ± 19.7 | 82.7 ± 18.6 | < 0.001 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 79.3 ± 21.6 | 78.7 ± 19.8 | 0.76 |

| Killip class 3 or 4, n (%) | 16 (13.1) | 137 (7.4) | 0.02 |

| Left bundle branch block, n (%) | 5 (4.1) | 19 (1.0) | 0.003 |

| TAVB, n (%) | 8 (6.6) | 48 (2.6) | 0.01 |

| Delta T, hour | 3.7 [1.9-6.2] | 3.9 [1.9-6.5] | 0.77 |

| Door-to-balloon time, hour | 1.4 [1.0-1.9] | 1.1 [0.8-1.5] | < 0.001 |

| Previous use of ASA, % | 49 (42.6) | 513 (28.2) | < 0.001 |

CAD: coronary artery disease; AMI: acute myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary angioplasty; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; TAVB: total atrioventricular block; ASA: acetylsalicylic acid.

LBBB or complete atrioventricular block (CAVB) were significantly more frequent in the elderly, as was the clinical presentation in Killip 3 or 4 functional class (13.1% vs. 7.4%; p = 0.02). Door-to-balloon time was longer in patients aged ≥ 80 years (1.4 hour [1.0-1.9 hour] vs. 1.1 hour [0.8-1.5 hour]; p < 0.001).

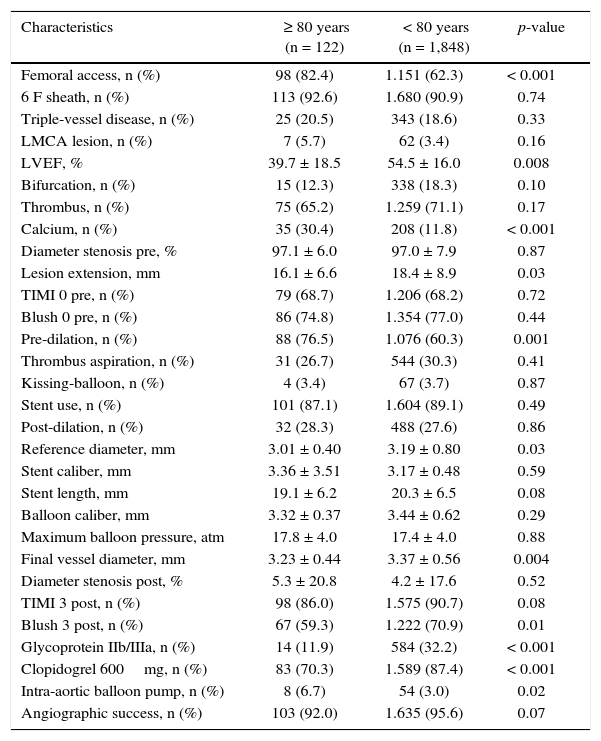

The patients’ angiographic profile was very similar between the groups, with the same number of patients with triple-vessel disease (20.5% vs. 18.6%; p = 0.33), but a lower ejection fraction in the group aged ≥ 80 years (39.7 ± 18.5% vs. 54.5 ± 16.0%; p = 0.008; Table 2).

Angiographic and procedure characteristics.

| Characteristics | ≥ 80 years (n = 122) | < 80 years (n = 1,848) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Femoral access, n (%) | 98 (82.4) | 1.151 (62.3) | < 0.001 |

| 6 F sheath, n (%) | 113 (92.6) | 1.680 (90.9) | 0.74 |

| Triple-vessel disease, n (%) | 25 (20.5) | 343 (18.6) | 0.33 |

| LMCA lesion, n (%) | 7 (5.7) | 62 (3.4) | 0.16 |

| LVEF, % | 39.7 ± 18.5 | 54.5 ± 16.0 | 0.008 |

| Bifurcation, n (%) | 15 (12.3) | 338 (18.3) | 0.10 |

| Thrombus, n (%) | 75 (65.2) | 1.259 (71.1) | 0.17 |

| Calcium, n (%) | 35 (30.4) | 208 (11.8) | < 0.001 |

| Diameter stenosis pre, % | 97.1 ± 6.0 | 97.0 ± 7.9 | 0.87 |

| Lesion extension, mm | 16.1 ± 6.6 | 18.4 ± 8.9 | 0.03 |

| TIMI 0 pre, n (%) | 79 (68.7) | 1.206 (68.2) | 0.72 |

| Blush 0 pre, n (%) | 86 (74.8) | 1.354 (77.0) | 0.44 |

| Pre-dilation, n (%) | 88 (76.5) | 1.076 (60.3) | 0.001 |

| Thrombus aspiration, n (%) | 31 (26.7) | 544 (30.3) | 0.41 |

| Kissing-balloon, n (%) | 4 (3.4) | 67 (3.7) | 0.87 |

| Stent use, n (%) | 101 (87.1) | 1.604 (89.1) | 0.49 |

| Post-dilation, n (%) | 32 (28.3) | 488 (27.6) | 0.86 |

| Reference diameter, mm | 3.01 ± 0.40 | 3.19 ± 0.80 | 0.03 |

| Stent caliber, mm | 3.36 ± 3.51 | 3.17 ± 0.48 | 0.59 |

| Stent length, mm | 19.1 ± 6.2 | 20.3 ± 6.5 | 0.08 |

| Balloon caliber, mm | 3.32 ± 0.37 | 3.44 ± 0.62 | 0.29 |

| Maximum balloon pressure, atm | 17.8 ± 4.0 | 17.4 ± 4.0 | 0.88 |

| Final vessel diameter, mm | 3.23 ± 0.44 | 3.37 ± 0.56 | 0.004 |

| Diameter stenosis post, % | 5.3 ± 20.8 | 4.2 ± 17.6 | 0.52 |

| TIMI 3 post, n (%) | 98 (86.0) | 1.575 (90.7) | 0.08 |

| Blush 3 post, n (%) | 67 (59.3) | 1.222 (70.9) | 0.01 |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa, n (%) | 14 (11.9) | 584 (32.2) | < 0.001 |

| Clopidogrel 600mg, n (%) | 83 (70.3) | 1.589 (87.4) | < 0.001 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump, n (%) | 8 (6.7) | 54 (3.0) | 0.02 |

| Angiographic success, n (%) | 103 (92.0) | 1.635 (95.6) | 0.07 |

LMCA: left main coronary artery; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

Regarding the procedure, femoral access was more often used (82.4% vs. 62.3%, p < 0.001), and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors and 600mg clopidogrel were less used in patients older than 80 years. Pre-dilation was used more frequently in the elderly, and -Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 3 flow post-procedure showed no difference between the groups (86% vs. 90.7%; p = 0.08), but post-Blush 3 was significantly lower in the patients aged ≥ 80 years (59.3% vs. 70.8%; p = 0.01). Angiographic success was achieved in 92.0% vs. 95.6% (p = 0.07).

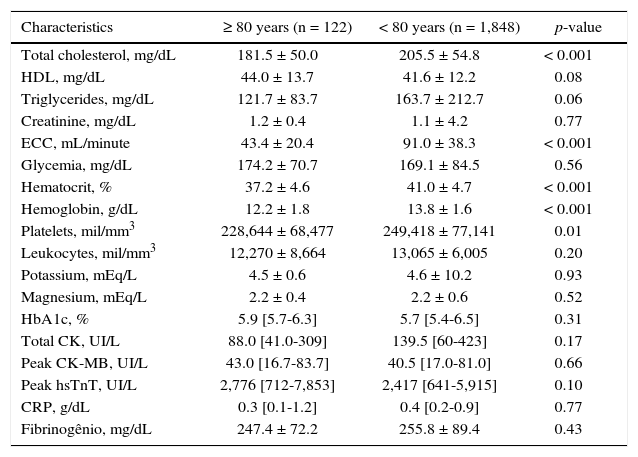

The laboratory characteristics are shown in Table 3. Markers of myocardial injury, such high-sensitivity troponin T (2,776 IU/L [712-7,853 IU/L] vs. 2,417 IU/L [641-5,915 IU/L]; p = 0.10) and creatine kinase MB isoenzyme (CK-MB; 43.0 IU/L [16.7-83.7 IU/L] vs. 40.5 IU/L [17.0-81.0 IU/L]; p = 0.66) were similar between the groups.

Laboratory characteristics.

| Characteristics | ≥ 80 years (n = 122) | < 80 years (n = 1,848) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 181.5 ± 50.0 | 205.5 ± 54.8 | < 0.001 |

| HDL, mg/dL | 44.0 ± 13.7 | 41.6 ± 12.2 | 0.08 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 121.7 ± 83.7 | 163.7 ± 212.7 | 0.06 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 4.2 | 0.77 |

| ECC, mL/minute | 43.4 ± 20.4 | 91.0 ± 38.3 | < 0.001 |

| Glycemia, mg/dL | 174.2 ± 70.7 | 169.1 ± 84.5 | 0.56 |

| Hematocrit, % | 37.2 ± 4.6 | 41.0 ± 4.7 | < 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 12.2 ± 1.8 | 13.8 ± 1.6 | < 0.001 |

| Platelets, mil/mm3 | 228,644 ± 68,477 | 249,418 ± 77,141 | 0.01 |

| Leukocytes, mil/mm3 | 12,270 ± 8,664 | 13,065 ± 6,005 | 0.20 |

| Potassium, mEq/L | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 4.6 ± 10.2 | 0.93 |

| Magnesium, mEq/L | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 0.52 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.9 [5.7-6.3] | 5.7 [5.4-6.5] | 0.31 |

| Total CK, UI/L | 88.0 [41.0-309] | 139.5 [60-423] | 0.17 |

| Peak CK-MB, UI/L | 43.0 [16.7-83.7] | 40.5 [17.0-81.0] | 0.66 |

| Peak hsTnT, UI/L | 2,776 [712-7,853] | 2,417 [641-5,915] | 0.10 |

| CRP, g/dL | 0.3 [0.1-1.2] | 0.4 [0.2-0.9] | 0.77 |

| Fibrinogênio, mg/dL | 247.4 ± 72.2 | 255.8 ± 89.4 | 0.43 |

HDL: high density lipoprotein; ECC: endogenous creatinine clearance; HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin; CK: creatine kinase; CK-MB: creatine kinase MB isoenzyme; hsTnT: highsensitivity troponin T; CRP: C-reactive protein.

Patients aged ≥ 80 years more often required a temporary pacemaker (11.8% vs. 4.5%; p < 0.001) during hospitalization and also showed significantly higher rates of severe arrhythmias or aborted sudden death (20.3% vs. 7.2%; p < 0.001). Respiratory dysfunction requiring mechanical ventilation (18.6% vs. 7.3%; p < 0.001) and acute renal failure (11.0% vs. 3.5%; p < 0.001) were more prevalent in this group of patients.

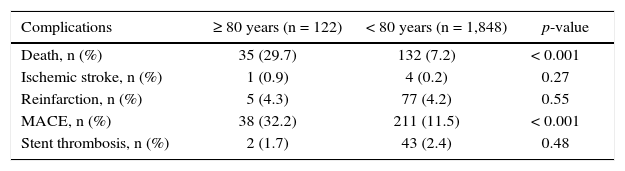

The rates of combined major cardiovascular events and death at 30 days were statistically more frequent in the group aged ≥ 80 years (32.2% vs. 11.5% and 29.7% vs. 7.2%; p < 0.001). Complications such as stroke, reinfarction, and stent thrombosis were not different between the groups (Table 4).

Complications and clinical outcomes at 30 days.

| Complications | ≥ 80 years (n = 122) | < 80 years (n = 1,848) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Death, n (%) | 35 (29.7) | 132 (7.2) | < 0.001 |

| Ischemic stroke, n (%) | 1 (0.9) | 4 (0.2) | 0.27 |

| Reinfarction, n (%) | 5 (4.3) | 77 (4.2) | 0.55 |

| MACE, n (%) | 38 (32.2) | 211 (11.5) | < 0.001 |

| Stent thrombosis, n (%) | 2 (1.7) | 43 (2.4) | 0.48 |

MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events.

The in-hospital evolution of patients aged ≥ 80 years was definitely less favorable in Brazil, with very high rates of mortality and complication. This result was observed regardless of the high rate of angiographic success.

Several registries have shown that advanced age is an independent factor for in-hospital mortality, together with hemodynamic instability, chronic kidney disease (CKD), diabetes, and multi-vessel disease.8–10 This result can be even worse when an nonagenarian is compared with a octogenarian patient.11,12

The presence of a greater number of comorbidities in this group was observed in this cohort and may justify such unfavorable evolution.1 Previous heart failure, diabetes, CKD, pulmonary disease, and previous AMI were more prevalent in very elderly patients. Additionally, antiplatelet agents were less commonly used in these patients. Previous studies showed an association between advanced age and poor evolution regardless of the reperfusion strategy. In addition to the identified factors associated with increased risk, other non-measurable aspects, such as fragility and homeostatic reserve, may contribute to a poor outcome.6 In a previous registry, age > 85 years, but not age > 75 years, was an independent predictor of mortality at 30 days.13

The estimated total ischemic time was longer, due to the greater delay in the door-to-balloon time in the group aged ≥ 80 years. Difficulties in the diagnosis or treatment of complications at presentation can be determinant factors of intervention delay. As previously acknowledged, there is a strong association between delayed care and mortality.10,13

Signs of severe ventricular dysfunction (Killip 3 or 4) at presentation were more frequent in the group aged ≥ 80 years. This factor is associated with worse in-hospital evolution in AMI.11 Similarly, advanced conduction disorders occurred more commonly in this age group and may be associated with worse prognosis. Earlier diagnosis and treatment could reduce the rate of patients with hemodynamic impairment.

CKD is one of the main factors associated with a poorer outcome in AMI.1 It is known that CKD is associated with coagulation disorders and higher rates of bleeding and thrombosis, in addition to more calcified lesions.

The preferred vascular access in the elderly was the femoral route. During the analyzed period, the femoral access was still preferred in urgency situations in Brazil. More recently, there has been a reversal in the utilization rates of the radial access, as lower rates of complications and mortality have been demonstrated. Patients at a very advanced age may present more complex radial artery anatomy, such as marked tortuosity, vascular calcification, and small-vessel caliber. However, the learning curve with the technique has allowed greater success with a lower rate of vascular complications.14

Study limitationsThis was an observational study; conclusions about the effect of therapies on outcomes may have been affected by confusion bias. Angiographic analysis was not independently assessed by a distinct angiographic laboratory, a limitation that is also shared by other studies of patients with primary coronary angioplasty. Finally, the long-term follow-up of these patients is not yet available, but short-term outcomes are known to be important and reliable in assessing the outcomes of patients with AMI.

ConclusionsIn this contemporary analysis, patients aged ≥ 80 years submitted to primary percutaneous coronary intervention had a more severe clinical and angiographic profile, longer door-to-balloon time, lower final Blush 3, and higher rates of in-hospital complications and 30-day mortality when compared with younger patients.

With the aging of the population, the care of these patients with acute myocardial infarction should progressively increase, as well as the use of interventional strategies and antiplatelet therapy, imposing the need for improvements in the diagnosis and treatment of these patients, aiming to improve outcomes for this population group.

Funding sourcesNone.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer review under the responsibility of Sociedade Brasileira de Hemodinâmica e Cardiologia Intervencionista.