Mental problems and disorders are prevalent in the adolescent population. It is estimated that around 10% of adolescents have mental disorders that require attention and are generally not recognised as such. The aim was to determine potential factors associated with whether or not mental disorders and problems are recognised in the Colombian population.

MethodsAdolescents aged 12–17 who said they had been diagnosed with a mental health problem or disorder by a healthcare professional were identified from the National Mental Health Survey conducted in Colombia in 2015. This group was compared with those who scored positive for mental disorders measured by CIDI 3.0 or mental problems detected by SRQ-20.

ResultsA sample of 1754 adolescents was obtained, of whom 7.3% (n = 129) had disorders and 22.6% (n = 396) had problems. Of the total with disorders and problems, 13.9% (n = 18) of people with disorders and 8.3% (n = 33) with problems knew they had them. Bivariate analyses were performed with the possible related variables, and with the results we constructed a multivariate regression model that identified factors associated with the recognition of disorders or problems, such as family dysfunction (OR = 2.5; 95% CI, 1.3−4.5) or counting on family when having financial problems (OR = 2.7; 95% CI, 1.0−7.2).

ConclusionsRecognition is of great importance for initiating access to care by adolescents. The results provide associated variables which can aid planning of interventions to improve the detection of disorders and problems in this population.

Los problemas y los trastornos mentales son prevalentes en la población adolescente. Se calcula que alrededor de un 10% de los adolescentes sufren trastornos mentales que requieren atención y, en general, no se reconocen como tales. El objetivo es determinar potenciales factores asociados con que se reconozcan o no los trastornos y problemas mentales en la población colombiana.

MétodosDe la Encuesta Nacional de Salud Mental (ENSM) del 2015 realizada en Colombia, se recogió a los adolescentes de 12–17 años que respondieron a si algún profesional los había diagnosticado un problema o trastorno de salud mental y se los comparó con los que puntuaron positivo en trastornos mentales medidos por el CIDI 3.0 o en problemas mentales detectados por el SRQ-20.

ResultadosSe obtuvo una muestra de 1.754 adolescentes, de los que el 7,3% (n = 129) tenían trastornos y el 22,6% (n = 396) tenían problemas. Del total con trastornos y problemas, reconocen que los tienen el 13,9% (n = 18) de las personas con trastornos y el 8,3% (n = 33) de aquellos con problemas. Se realizaron análisis bivariables con posibles variables relacionadas y, con los resultados, se construyó un modelo multivariable de regresión que evidenció factores asociados con el reconocimiento de trastornos o problemas, como disfunción familiar (OR = 2,5; IC del 95%, 1,3–4,5) y acudir a familiar en caso de problemas económicos (OR = 2,7; IC del 95%, 1,0–7,2).

ConclusionesEl reconocimiento es de gran relevancia para que los adolescentes inicien el acceso a la asistencia. Los resultados proveen variables asociadas que permiten planear intervenciones que promuevan la detección de trastornos y problemas en esta población.

Adolescence is understood from all perspectives (biological, psychological, social and cultural) as a moment of transition, of change, from childhood to adulthood, in which the individual undergoes a process of identification in relation to themselves and society.1 This period of transition and change can be affected to a considerable extent by psychopathological processes and mental illness, with prevalences that vary by region, but that can exceed 10% of adolescents.2,3 Similarly, it has widely been described that first uses of psychoactive substances occurs during adolescence and is often associated with mental illness.4,5

The burden and deterioration of mental illnesses have a significant impact on the quality of life of adolescents, limiting their progress in education as well as entry into the workforce. However, this impact becomes even more drastic when exploring the causes of mortality in the adolescent population, in particular suicide, which is strongly related to the presence of mental illnesses, and the use of psychoactive substances.6–9 Despite our knowledge of this impact, access to mental health services is lacking for the adolescent population, with most studies finding that just 20–40% of adolescents with mental health problems or a mental illness receive or access any type of mental health care.10–12

The process of accessing healthcare is a dynamic construct within which different areas and aspects interacts and various actors (users, healthcare professionals, politicians, the general community, governments) play a role, and mental illness is no exception. Leaving behind old conceptions of access to healthcare as exclusively a relationship between supply and demand of services, in the case of the adolescent population, the relationship of dependency they have with caregivers and parents, as well as their own and others' recognition of their health needs, must also be taken into account.13–15 The World Health Organisation has clearly and conclusively identified a deficiency in the provision of mental health services for children and adolescents, beginning with the legislative aspects that secure or support these services, as well a gulf between low and high income countries in adolescents' access to mental health services.16–18

Nevertheless, the lack of available services and resources for adolescent mental healthcare has not been the foremost cause of the greatest barrier to mental health access, the lack of auto-recognition. The vast majority of studies have shown that attitudinal barriers and lack of recognition are the predominant reasons for not accessing mental health services.19 Of the so-called attitudinal barriers, the most frequently observed is that related to the stigmatisation and discrimination associated with mental illness, followed by lack of knowledge or education about mental illness processes, which limits adolescents' ability to recognised them.19–21

In the case of Colombia, the most recent National Mental Health Survey (ENSM) found that, in the 12–17 years age group (n = 1754), 1.8% of respondents reported having had mental health problems during their life, only half of them (51.7%) presented these problems in the last 12 months, and of these just 36.5% had received any type of treatment in this period; it is not possible to identify their reason or reasons for not having accessed mental health services or at least recognised the problem.22 As can be seen, there is a vacuum in the country as to the reasons or factors associated with the failure to recognise mental health problems or disorders in adolescents, and it is that which has motivated this work.

MethodsThe work presented here is based on the data obtained in the 2015 ENSM, a nationally representative study with selection from the Colombian Ministry of Health and Social Protection' master sample. The population consisted of all non-institutionalised people over 7 years of age, with a type of random sampling of households. The ENSM was representative of the 5 regions selected and defined adolescents as the population aged 12–17 years (for more information on the sampling methodology, see the publications related to the ENSM).23 Where respondents were minors (under 18 years of age for the ENSM), the minor's assent and their guardian's consent were obtained for the interview. Adolescents were administered the mental disorders questionnaire (Composite Internal Diagnostic Interview [CIDI] 3.0) designed for this groups, and the Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ) for mental disorders.24,25

Sociodemographic characteristics were collected based on previous studies conducted by the Colombian National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE), such as questions relating to the multidimensional poverty index (MPI) and the classification of households as rural or urban26. With regard to the questions and variables relating to the perception of supports from third parties, emotional support, economic support, trust in others and feelings of discrimination, among others, these were designed and set specifically for this ENSM and validated prior to use.27,28

With regard to determining psychopathology or substance use disorders, instruments validated globally and in Colombia were used, such as the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), the SRQ-20 to assess mental health problems and the CIDI 3.0 to diagnose mental health disorders. Autorecognition of psychopathology by the adolescents was determined by asking whether the adolescent had ever been told by a healthcare professional that they had nervous, mental health or learning problems.

From this data, variables associated with recognition of mental illness in adults and adolescents were investigated, including sociodemographic variables, perception of the working environment, feelings of discrimination, support from third parties, use of psychoactive substances, socioeconomic variables and family dysfunction. Participants’ recognition was compared with the presence of a mental health disorder as defined by the CIDI or a mental health problem identified by the SRQ-20.24,25

Firstly, as part of the analysis, the percentage distribution of individuals across the categories of each nominal and ordinal variable was observed, with some of these being found to have low frequencies. To obtain better results in the bivariate analyses and logistic model, recategorisation was carried out, taking into account the clinical importance of certain variables. Similarly, the continuous variables were categorised and variables were constructed―suffering chronic illnesses, feelings of discrimination, participation in groups and trust of third parties―from the answers to the survey, paying attention once again to the clinical importance of the categorisation.

Bivariate cross-tabulation was then carried out for each of the variables mentioned against the variable of recognition of a mental problem or disorder. Those with a p value of <0.20 were subsequently selected to form a multivariate model. The variables in the multivariate logistic regression model were selected using the stepwise methodology and a significance level of 5% to define those to be retained in the final model. Each model uses the odds ratio (OR) and its corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) as a measure of association. The data were processed using the program STATA version 15.

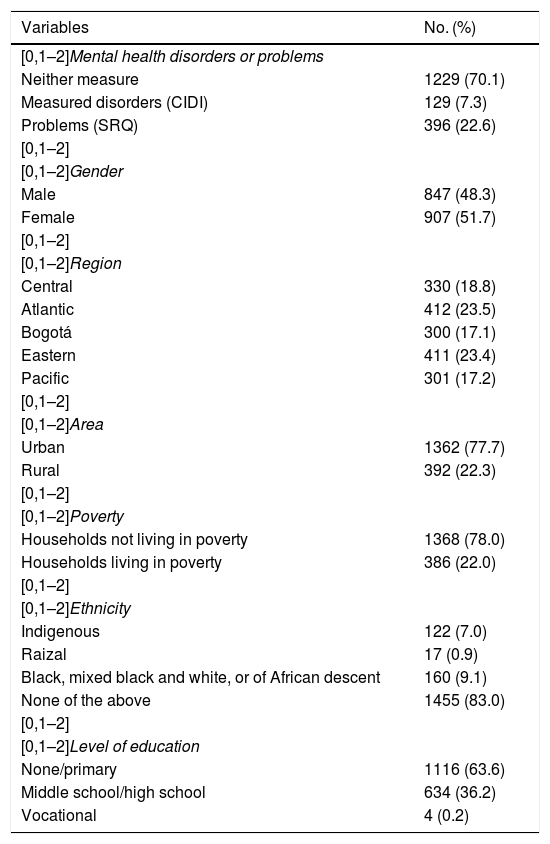

ResultsThe entire sample was made up of 1754 adolescents from 12 to 17 years of age, of whom 22.6% reported possible mental health problems―based on the SRQ―and 7.3% a mental health disorder―as measured by the CIDI―during their life. The sample is homogeneous in terms of gender, with the Atlantic (Caribbean) and Eastern regions being slightly overrepresented. Approximately 22% of the adolescents lived in rural areas and came from household living in poverty based on the MPI (Table 1).

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample of adolescents (n = 1754). ENSM 2015.

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| [0,1–2]Mental health disorders or problems | |

| Neither measure | 1229 (70.1) |

| Measured disorders (CIDI) | 129 (7.3) |

| Problems (SRQ) | 396 (22.6) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Gender | |

| Male | 847 (48.3) |

| Female | 907 (51.7) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Region | |

| Central | 330 (18.8) |

| Atlantic | 412 (23.5) |

| Bogotá | 300 (17.1) |

| Eastern | 411 (23.4) |

| Pacific | 301 (17.2) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Area | |

| Urban | 1362 (77.7) |

| Rural | 392 (22.3) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Poverty | |

| Households not living in poverty | 1368 (78.0) |

| Households living in poverty | 386 (22.0) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Ethnicity | |

| Indigenous | 122 (7.0) |

| Raizal | 17 (0.9) |

| Black, mixed black and white, or of African descent | 160 (9.1) |

| None of the above | 1455 (83.0) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Level of education | |

| None/primary | 1116 (63.6) |

| Middle school/high school | 634 (36.2) |

| Vocational | 4 (0.2) |

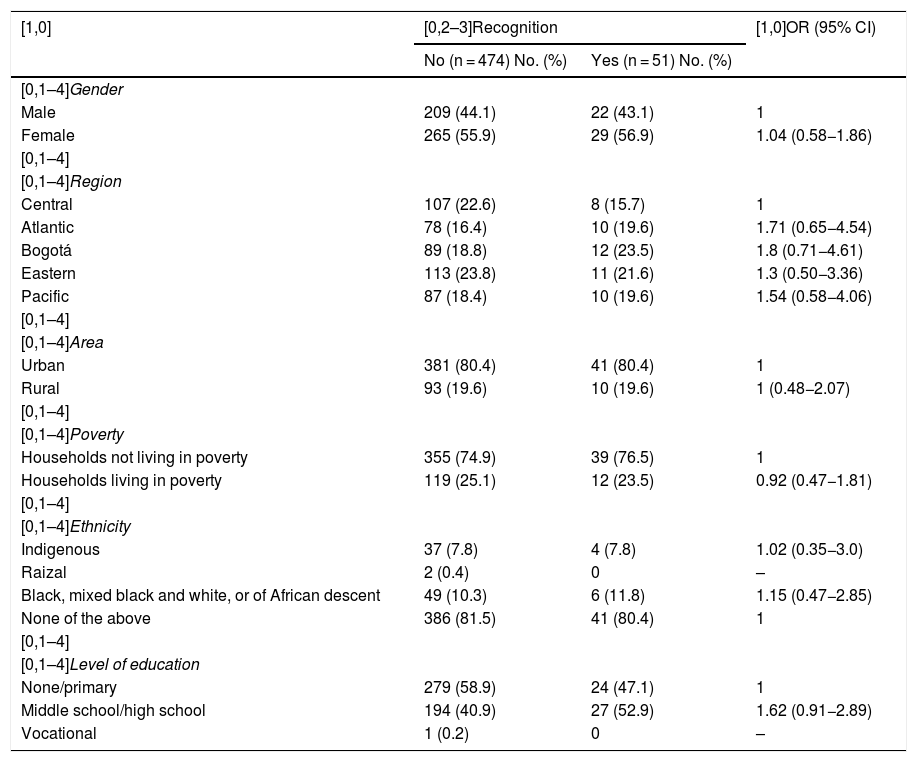

Of the patients with mental health problems or disorders, no variables associated with greater or lesser recognition of their mental health problem were observed in either group, regardless of gender, region, area, poverty level, ethnicity or level of education. It was thought that this could be due to the low number of people who recognised their problem (33 out of 399) or disorder (18 out of 129). For this reason, the decision was made to aggregate problems and disorders in a single group for analysis, in order to increase the power and precision of the sample. A similar result was obtained, but with greater precision than for either individually, and no sociodemographic variable was found to be associated with recognition of mental health problems or disorders (Table 2).

Factors associated with recognition of mental health disorders and problems: bivariate analysis.

| [1,0] | [0,2–3]Recognition | [1,0]OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 474) No. (%) | Yes (n = 51) No. (%) | ||

| [0,1–4]Gender | |||

| Male | 209 (44.1) | 22 (43.1) | 1 |

| Female | 265 (55.9) | 29 (56.9) | 1.04 (0.58−1.86) |

| [0,1–4] | |||

| [0,1–4]Region | |||

| Central | 107 (22.6) | 8 (15.7) | 1 |

| Atlantic | 78 (16.4) | 10 (19.6) | 1.71 (0.65−4.54) |

| Bogotá | 89 (18.8) | 12 (23.5) | 1.8 (0.71−4.61) |

| Eastern | 113 (23.8) | 11 (21.6) | 1.3 (0.50−3.36) |

| Pacific | 87 (18.4) | 10 (19.6) | 1.54 (0.58−4.06) |

| [0,1–4] | |||

| [0,1–4]Area | |||

| Urban | 381 (80.4) | 41 (80.4) | 1 |

| Rural | 93 (19.6) | 10 (19.6) | 1 (0.48−2.07) |

| [0,1–4] | |||

| [0,1–4]Poverty | |||

| Households not living in poverty | 355 (74.9) | 39 (76.5) | 1 |

| Households living in poverty | 119 (25.1) | 12 (23.5) | 0.92 (0.47−1.81) |

| [0,1–4] | |||

| [0,1–4]Ethnicity | |||

| Indigenous | 37 (7.8) | 4 (7.8) | 1.02 (0.35−3.0) |

| Raizal | 2 (0.4) | 0 | – |

| Black, mixed black and white, or of African descent | 49 (10.3) | 6 (11.8) | 1.15 (0.47−2.85) |

| None of the above | 386 (81.5) | 41 (80.4) | 1 |

| [0,1–4] | |||

| [0,1–4]Level of education | |||

| None/primary | 279 (58.9) | 24 (47.1) | 1 |

| Middle school/high school | 194 (40.9) | 27 (52.9) | 1.62 (0.91−2.89) |

| Vocational | 1 (0.2) | 0 | – |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: crude odds ratio.

For the other variables, associated or otherwise with recognition of the mental health disorder or problem, bivariate cross-tabulation was carried out for possible associated variables. In this case, an association was revealed between greater recognition of illness and feeling discriminated against (OR = 2.0; 95% CI 1.1–3.5), feeling that one might be discriminated against because of a mental health disorder (OR = 29.3; 95% CI 3.1–278.3) and feeling that one could turn to a partner when having problems (OR = 2.8; 95% CI 1.1–7.4). Subjects also showed less recognition of illness when they discriminated against another person because of their religion (OR = 0.2; 95% CI 0.1−0.8).

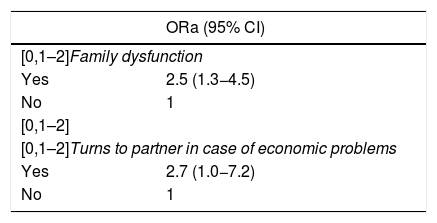

Lastly, the results of the multivariate regression model revealed a link between recognition of mental health disorders and problems and the presence of family dysfunction and ability to turn to another person when having problems (Table 3).

DiscussionThe autorecognition process is fundamental to and essentially the first step in the process of accessing health services, not only in the case of mental illness, but in any type of disease.29,30 In the case of young people, this process is very necessary since, as shown in some studies, the adolescent themselves needs to have recognised their mental health problem or disorder in order to facilitate not only access, but also the involvement of their parents, teachers or other adults around them.10,31 The information collected in the context of the ENSM facilitated the identification of variables associated with the recognition process, thanks to the participation of more than 1500 young people on the country who responded to the questionnaires in full.

In the results of the bivariate model, it is notable that variables such as female gender did not display any significant association. Findings regarding the association between recognition and female gender have been mixed, with some studies showing a greater association with autorecognition32 and others not identifying any type of association.33 Some authors justify these differences with the explanation that studies that found a greater association with autorecognition may have included younger adolescents.34 In this study, no association was found between female gender and greater recognition, which could be explained by the change that has been detected in adolescence in recent years, and above all with respect to women, who increasingly present themselves as stronger and equal to men. This could be supported by the fact that the article that found greater recognition is from 2003,32 while the one showing no differences is from 2013.33 However, this point derives from clinical and social observations and requires more in-depth study.

Households living in rural areas or in poverty according to the MPI, did not have any type of association with recognition of a mental health problem or disorder in the ENSM. Results are found in the literature that show a greater association between poverty or lower income or fewer family resources and autorecognition,32,33 as well as others that show no association with regard to measures of variables relating to income, poverty or socioeconomic level.35,36

These differences in the results can be explained primarily by the use of different measures or scales relating to poverty and income variables. For this reason, it has sometimes been proposed that variables that can be linked to economic determinants, such as employment, education or living conditions be used and compared.37,38

The age of the adolescents likewise showed no changes in autorecognition of mental health problems or disorders, although with increasing age there was an increase in introspection, greater participation in society and reduced dependency on adults compared to younger adolescents (12–15 years of age).39,40 These findings are in keeping with those reported in other countries, such as Spain,41 the Netherlands42 and New Zealand,43 where the older the adolescent, the greater their autorecognition and perception of the need for care for mental health problems compared to younger adolescents. This was not observed in Colombia, which may be due to the tendency to live for longer in the family home, which would lead them to be more dependent on their families, and therefore differentiate themselves less in this age group, or to other cultural factors that require future study.

With regard to education, adolescents with middles school, high school or more advanced studies, compared to those with only a primary or no education, had greater recognition of mental health problems and disorders. This result contrasts with published findings, which either indicate that there is an association between a lower level of education and recognition and perception of the need for care with regard to mental health32 or find no association between level of education and autorecognition.44 There is currently a need for more studies comparing the recognition and autorecognition outcome, which was not measured precisely in this study due to the type of question asked; interviewees were asked whether a professional had detected or diagnosed them with a mental health problem or disorder, which could depend, to a large extent, on which the patient suggests and says to the physician, even more so in a setting where the detection of mental illness by healthcare professionals is so rare and where stigmatisation and self-stigmatisation can reduce access.45 Concurrently, the possibility needs to be considered that in our setting a higher level of education favours health literacy and therefore recognition and autorecognition during the medical act, wherein a person who is aware of their own disorder can more rapidly access consultations and talk to a healthcare professional about their complains, which brings with it a greater opportunity or likelihood that said professional will recognise it.

Discrimination in adolescence has been particularly visible recently though what have become known as the anti-bullying movements, thanks to the well established link between suffering these discriminatory behaviours and presenting mental illnesses.46,47 In the bivariate analysis, it could be seen that having been or felt discriminated against due to mental illness was associated with greater recognition. Meanwhile in the bivariate model, discriminating due to religion was associated with reduced recognition, a finding that was not repeated in the multivariate analysis after controlling for other variables. However, due to the low number of events, it is thought that these associations should be investigated in more depth with further studies. To date, it is known that being discriminated against on mental health problems or racial grounds can limit communication of mental health problems, but recognition and perception of need processes have not been evaluated in those with discriminatory behaviours.20,48

It is worth noting that having had a mental health disorder or history of substance use was not associated with greater recognition, although the literature shows more autorecognition, perception of need for care and use of healthcare services in adolescents who have suffered from mental health problems or disorders.43,44,49 There are two points that might explain this difference: firstly, some of the studies that found such associations used different instruments to those used in this study, and these may behave different; secondly it could be due to the low prevalence of mental health disorders measured (7.2% ever, 4.4% in the last year and 3.5% in the last month) compared with other prevalences that range from 10% to 20% when other conditions are included.2,3,34

Having emotional support from family was not associated with recognition of psychopathology by adolescents but, although the bivariate model did not reach statistical significance, having support from friends did show a tendency towards greater recognition. These results are consistent and in keeping with the international literature, in which it has been seen that having more support from third parties leads to greater autorecognition.36,42,49 Support from third parties is one way of confronting and coping with mental health problems, but for adolescents, the third parties they most trust are often peers of the same age or friends, who may at times replace professionals but in some illnesses may suggest a consultation.36,50 On the other hand, in the bivariate analysis it can be seen that those who turn to a partner when experiencing difficulties can have more recognition of their problems; this is in keeping with what is indicated in the literature.51

Not having a history of chronic illness was found to have a greater association with lack of recognition in this cohort of adolescents. This situation can be explained by the fact that, those without chronic conditions had less contact with healthcare services, which might compromise the knowledge and education on the subject of maintaining their health, as well as the possible identification of other illnesses should a problem arise. Similar findings are reported in other studies, with the difference that in those studies suffering chronic illnesses was used as an endpoint and was associated with increased autorecognition and perceived of the need for healthcare.33,36,49

The perception of worse or poor mental health highlights the fact that those who qualified their health in this way were capable of recognising in themselves the presence of psychological burdens or symptoms that altered their general well-being, generating a greater association with autorecognition as their perception of their mental health worsened. These finding of other studies10,36,49 did not appear in this work. Nevertheless, in the bivariate analysis greater recognition of mental illness was found in those people who felt discriminated against, in particular when this was because of mental health disorders.

This study's limitations begin with those of any cross-sectional design, in which it is not possible to establish causality relationships, but merely likely associations that need to be explored in future studies with designs that permit causality relationships to be established. Moreover, it is subject to two main types of bias: memory bias, in asking about a history of certain variables such as traumatic events, and social desirability, due to which, in a subject like mental illnesses, some individuals may alter their response in the interviews to bring it more in line with what is expected in their community and social environment, as well as due to the stigmatisation and self-stigmatisation these illnesses generate. However, these problems were limited by having experts in this work and well trained staff administer the surveys, enabling good support and empathy when interviewing. Another difficulty that the study might have is that tests were not conducted for all mental illnesses, possibly limiting the results to only prevalent illnesses, which may not be representative of people with less common, unexplored illnesses.

The representative nature of an age group of adolescents from all over a country such as Colombia is, without any doubt, one of this study’s greatest strengths, since it allows its findings to be confidently extrapolated or applied to Colombian adolescents. In addition, the use of questionnaires that have undergone country-appropriate validation or adaptation processes (CIDI, SRQ, AUDIT) enabled greater control of measurement biases for the outcomes obtained. Finally, this study is, as far as we know, the first conducted in Latin America on the recognition process in adolescents, providing a baseline for future comparisons and the generation of studies in other countries in the region with social and cultural bases that are somewhat more similar than those in other parts of the world.

ConclusionsIt is well known that during adolescence various psychological processes occur that enable the transition from childhood to adult life. It is therefore necessary to adequately identify and recognise irregularities during this stage, in order to intervene early and to be aware of the variables associated with an increase or decrease in this recognition. Thanks to these findings, the first step can be taken in designing, proposing and applying strategies to control the variables associated with lower recognition and enhance those that favour recognition of mental illnesses in young Colombians.

Ethical responsibilitiesWork authorised by the Ethics Committee of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana [Pontifical Xavierian University].

FundingColombian National Mental Health Survey [Encuesta Nacional de Salud Mental]. Funding contract RC No. 762- 2013 between Colciencias [Colombian Administrative Department of Science, Technology and Innovation] and the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

To the Ministry of Health and Social Protection, for the loan of the National Mental Health Survey 2015 database.

Please cite this article as: Gómez-Restrepo C, Malagón NR, Eslava-Schmalbach J, Ruiz J, Gil JF. Factores asociados al reconocimiento de trastornos y problemas mentales en adolescentes en la Encuesta Nacional de Salud Mental, Colombia. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:3–10.