Depression is the most common psychiatric comorbidity in people with epilepsy. It worsens the prognosis and quality of life of these patients. Despite this, depression is poorly diagnosed and when the treatment is given, it is frequently suboptimal.

ObjectiveTo perform a narrative review of the medical literature, seeking to collect useful information regarding the relationship between epilepsy and depression.

ResultsNarrative reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, clinical trials, and follow-up studies were identified in English and Spanish with no time limit, including epidemiological, clinical, associated factors, etiological explanations, diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to comorbid depression in epilepsy.

ConclusionsThe relationship between epilepsy and depression is complex. The available scientific evidence suggests the possibility of a bidirectional relationship that could be explained from common aetiopathogenic mechanisms. Despite the high prevalence of depression in epileptic patients, this mental disorder continues to be poorly identified by clinicians. To improve this, we have easy-to-apply instruments that routinely screen this patient population and contribute substantially to making the problem more visible and seek to improve the quality of life for this population.

La depresión es la comorbilidad psiquiátrica más común en las personas con epilepsia, lo cual les empeora el pronóstico y la calidad. A pesar de esto, frecuentemente no se reconoce este problema y cuando se diagnostica, el tratamiento es subóptimo.

ObjetivoRealizar una revisión narrativa a partir de la literatura médica, buscando recopilar información útil sobre la relación entre epilepsia y depresión y la mejor forma de diagnosticarla y tratarla.

ResultadosSe identificaron revisiones de tema, revisiones sistemáticas, metanálisis, ensayos clínicos y estudios de seguimiento en inglés y español, sin límite de tiempo, que incluyen aspectos epidemiológicos, clínicos, factores asociados, explicaciones etiológicas y aproximaciones diagnósticas y terapéuticas de la depresión comórbida con la epilepsia.

ConclusionesLa relación entre epilepsia y depresión es compleja. Alguna evidencia científica disponible indica la posibilidad de una relación bidireccional, que podría explicarse a partir de mecanismos etiopatogénicos comunes. A pesar de la alta prevalencia de la depresión entre los pacientes epilépticos, los clínicos siguen identificando escasamente este trastorno mental. Para mejorar esto, se cuenta con instrumentos de fácil aplicación que permiten tamizar sistemáticamente a esta población de pacientes y contribuir de manera sustancial a hacer más visible el problema y procurar la mejora de la calidad de vida de estas personas.

Depression is the most common psychiatric disorder in people with epilepsy. The lifetime prevalence of depression in epilepsy has been estimated to be between 6 and 30% in population studies and up to 50% in high complexity medical centres.1–3 In addition to the negative impact on quality of life, depression is a predictor of worse response to pharmacological and surgical treatments.4,5 This high comorbidity has been suggested as the expression of a bidirectional and complex relationship, and, in turn, the indication of common pathogenic mechanisms.6

However, these symptoms are rarely searched for and identified and, when it is diagnosed, treatment is suboptimal, which deprives patients of the comprehensive care they require.7 The objective of this narrative review is to identify historical, epidemiological, pathophysiological, clinical and therapeutic aspects which enable a comprehensive and current perspective of depression in patients with epilepsy.

The first descriptions of psychiatric disorders in people with epilepsy were made in 1860 by Falret and Morel, who emphasised the recurrent features of the mental changes and fits of anger and rage that patients suffer from.8 Subsequently, Kraepelin argued that “recurrent dysphorias” represented the most common psychiatric disorders in people with epilepsy and that they are characterised by irritability, in addition to fits of anger, depressive affect, anxiety, insomnia and headache. Bleuler9 made similar descriptions. From this initial description, Blumer coined the term interictal dysphoric disorder.10

EpidemiologyThe prevalence of depression among people with epilepsy varies widely according to the diagnostic criteria used, the population studied and the study methodology.11 In the Canadian Community Health Survey Cycle, in a study which included a sample of 130,888 people, the prevalence of depression in epilepsy patients was 13.0%, while in the general population it was 7.2%.12 Oliveira et al. reported higher prevalences, from 22.0 to 27.6% in community-based studies, but with smaller samples.13,14 The highest prevalences (50.0%) were obtained in samples with epilepsy patients in tertiary care.15

Some epidemiological studies reported that major depressive disorder may precede and increase the risk of onset of epilepsy.16 In the context of a bidirectional relationship between both entities, not only do patients with epilepsy have a greater risk of developing depressive comorbidities, but patients with depression have a four to seven times higher risk of suffering from epilepsy.17–19

In a recent study, Josephson et al.20 studied 10,595,709 patients from the Canadian Health Network, of which 229,164 (2.2%) developed depression and 97,177 (0.9%) developed epilepsy. Incident epilepsy was associated with an increase in the risk of depression (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.04; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.97–2.09; p < 0.001) and incident depression was associated with a higher risk of epilepsy (HR = 2.55; 95% CI, 2.49–2.60; p < 0.001).

Despite the extensive literature that signals depression as the main psychiatric comorbidity in people with epilepsy, reports continue to indicate that depression is under-diagnosed and under-treated.21 Some of the explanations for this may be: a) low awareness of neurologists towards psychiatric symptoms, and b) an atypical clinical presentation of depressive disorders in patients with epilepsy, which would not make it possible to carry out the diagnosis according to the ICD or DSM criteria.22

With regard to suicide risk in individuals with epilepsy, it has been found that it is up to 10 times greater than in the general population.23,24 This has been related to the high prevalences of suicidal thoughts (36.7%), suicide plans (18.2%) and suicide attempts (12.1%) of these patients which have been reported.25

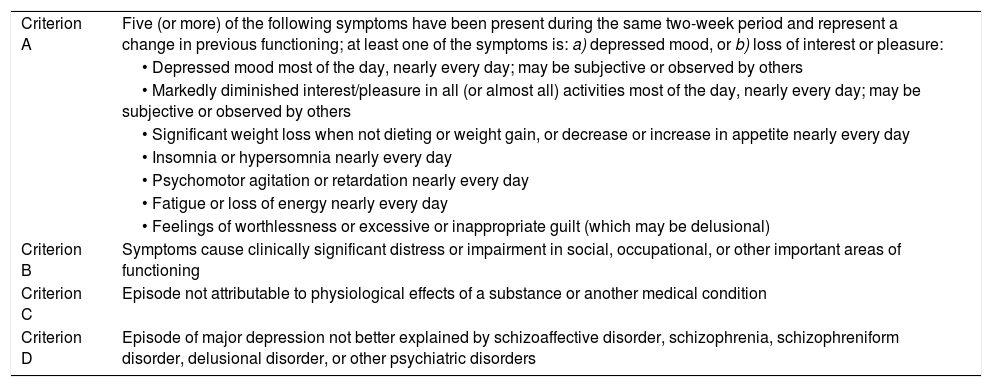

Clinical aspectsAccording to the DSM-5, a major depressive episode is defined by a markedly reduced interest in almost all life activities, accompanied by at least five of nine proposed symptoms and with a duration of at least two weeks (Table 1).

Diagnostic criteria of major depressive disorder according to DSM-5.30

| Criterion A | Five (or more) of the following symptoms have been present during the same two-week period and represent a change in previous functioning; at least one of the symptoms is: a) depressed mood, or b) loss of interest or pleasure: |

| • Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day; may be subjective or observed by others | |

| • Markedly diminished interest/pleasure in all (or almost all) activities most of the day, nearly every day; may be subjective or observed by others | |

| • Significant weight loss when not dieting or weight gain, or decrease or increase in appetite nearly every day | |

| • Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day | |

| • Psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day | |

| • Fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day | |

| • Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt (which may be delusional) | |

| Criterion B | Symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning |

| Criterion C | Episode not attributable to physiological effects of a substance or another medical condition |

| Criterion D | Episode of major depression not better explained by schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder, or other psychiatric disorders |

A diagnostic alternative is the scale for depression in epilepsy Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy (NDDI-E), which contains six self-applied questions which are responded to in less than three minutes; a score ≥15 indicates a major depressive episode with a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 90%, a positive predictive value of 62% and a negative predictive value of 96%.26 This scale is validated in Spanish, Portuguese, German, Italian and Japanese; although more studies are required to validate its use in epilepsy patients, it has the advantage that it is of unrestricted use.7,27

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is a brief and self-applicable inventory to evaluate symptoms of both anxiety and depression in medically ill patients. In Colombia, this scale is validated in cancer patients.28 The HADS was validated in epilepsy patients, with a cut-off point of 7, a sensitivity of 99% and a specificity of 87.5–100%.29

These scales facilitate screening, but some suggest28 that a mental health worker confirms the diagnosis, backing him/herself up with the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria that are shown in Table 1.30 The presence of depressed mood, common in patients with and without epilepsy, does not imply the clinical diagnosis of depression and does not require treatment when it is transient.31 On the other hand, anhedonia, anergia and social isolation, symptoms with significant depressive value, should not be “normalized” in this population.32

Other findings in depression associated with epilepsySome studies carried out in people with epilepsy show that depression and suicide risk are related to alterations in brain structures33,34 and to the metabolism of serotonin.35,36 Electrophysiological, biochemical and neuroimaging studies have found hypofrontality and increased tonsil size which lead to frontotemporal dysfunction.37

Temporality of affective symptoms in relation to epileptic seizuresThe temporality of affective symptoms in relation to epileptic seizures makes it possible to talk about depression symptoms as being pre-ictal, post-ictal or ictal. When the depression symptoms do not have any relationship to the ictal seizures, they are called interictal.23,38

Pre-ictal depressive episodes or symptomsDepressed mood and irritability may occur as prodromal episodes, which manifest hours or days before the epileptic seizure and, frequently, the symptoms are resolved with the onset of the seizure.39 In a prospective study, Blanchet and Frommer40 monitored 27 patients with different types of epilepsy for at least 56 days, and found that 13 patients had at least one seizure. The depression scales showed a higher number of depression symptoms on the days prior to the seizure. This coincides with what is reported by Kanner et al.28

Ictal depressive episodes or symptomsDepression symptoms may be ictal phenomena and, as such, are a simple partial seizure. This affective manifestation of an ictal phenomenon is difficult to identify for the non-trained observer. Therefore, they frequently go unnoticed and are interpreted as affective symptoms not related to an epileptic phenomenon. In order to identify these depression symptoms more easily, the following characteristics should be taken into account: a) the symptoms are brief; b) they are stereotyped; c) they occur out of context; and d) they may be associated with other ictal phenomena.28 Ictal depression may be more common in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy41, although in 25% of aurae there are psychiatric symptoms and in 15% of these aurae they include affective symptoms.42

Post-ictal depressive episodes or symptomsDepression symptoms of varying duration have been reported after an epileptic seizure. Although it is rare to find patients with isolated post-ictal depressive episodes, most of them also suffer from interictal depressive episodes. Post-ictal depressive episodes occur more frequently after simple partial seizures originating in right temporal structures.8

In a study carried out at the Rush Epilepsy Center with 100 poorly-controlled epilepsy patients, 43% of them suffered from post-ictal depression symptoms. Of the patients with depression symptoms, 13 reported seven or more depression symptoms, with a mean duration of 24 h, and 13 patients admitted having had suicidal thoughts.43

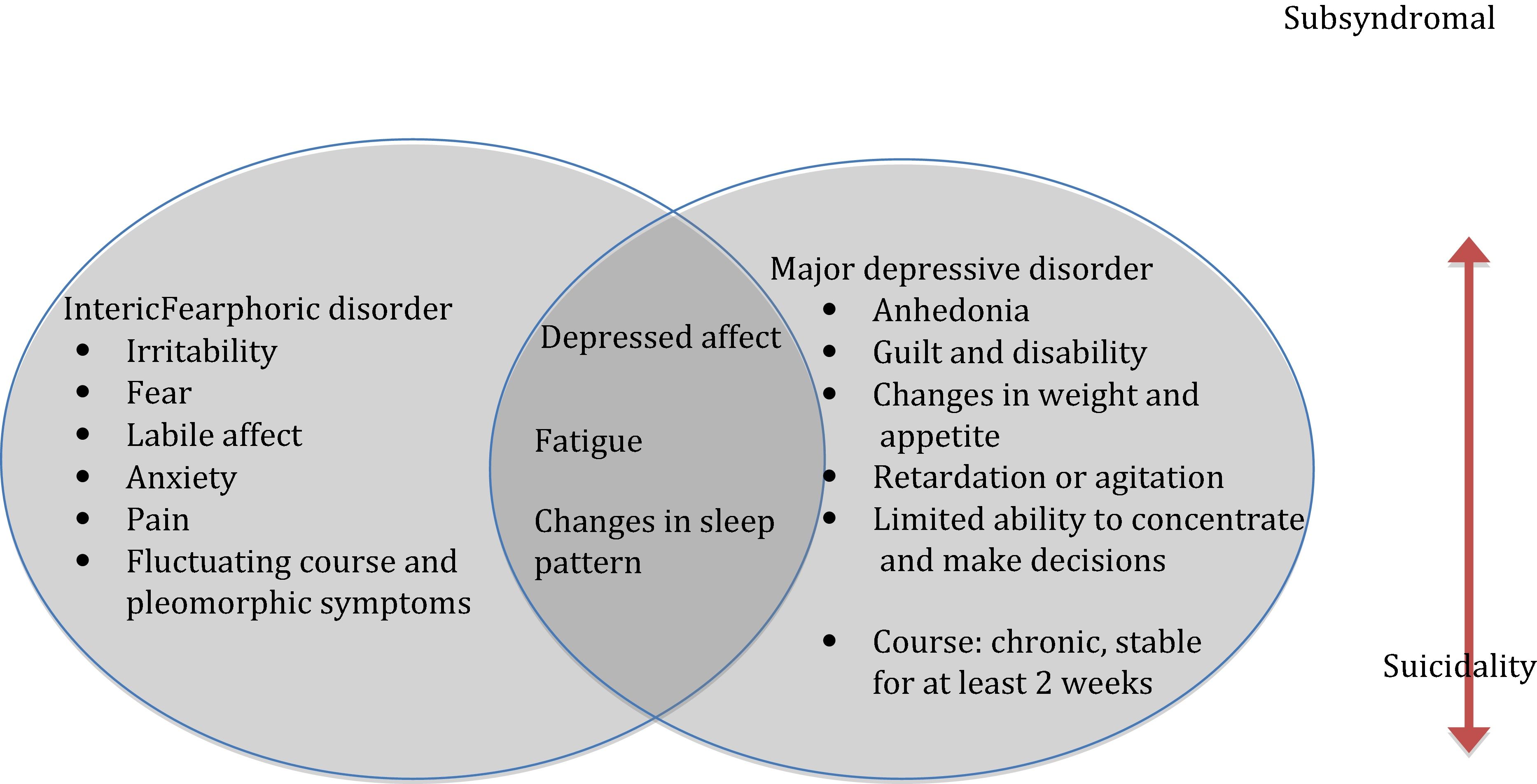

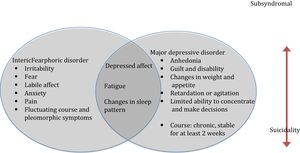

Interictal depressive episodes or symptomsInterictal depressive episodes are more prevalent than episodes directly related to the epileptic seizure. A total of 25–50% of these depressive episodes do not comply completely with the conventional diagnostic criteria and are accompanied by atypical characteristics which have already been described (Fig. 1).28

In a classic study by Mendez et al.,44 who described the semiology of depression in 175 patients with epilepsy, it was found that 22% could be classified with atypical characteristics, and the depression symptoms considered typical of endogenous depression, such as altered circadian rhythms and feelings of guilt, were rare in these patients. Subsequently, Kanner et al. found that 71% of patients with refractory epilepsy and severe depressive episodes did not meet the depression criteria of the DSM-IV.45,45bis

Interictal dysphoric disorderThe depressive disorders of people with epilepsy are presented in a multi-faceted way. They may be manifested as groups of symptoms or appear as well-characterised disorders that meet the diagnostic criteria of the DSM-5. Some propose that the characteristics of these depression symptoms are atypical.39

Interictal dysphoric disorder describes a pleomorphic affective disorder in patients with epilepsy, characterised by eight symptoms: depressed mood, anergia, pain, insomnia, fear, anxiety, paradoxical irritability and euphoric mood. Some clinicians support this proposal, but there are not sufficient studies providing convincing evidence on the validity of the disorder.

In a study which included 229 patients (46.5% with epilepsy and 73.3% with migraine), depression scales were applied: the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), the Interictal Dysphoric Disorder Inventory (IDDI) and the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ). It was concluded that interictal dysphoric disorder represented a homogeneous construct, diagnosed in 17%, but that these symptoms were not typical of epilepsy and that they also presented in migraines. Although other studies have been carried out with this nosological proposal, more studies are required.46,47

Iatrogenic depressive episodes or symptomsIn 2008, the United States Food and Drugs Agency (FDA) issued a warning that “all antiepileptic drugs have the potential to cause suicidal thoughts and behavior”.48 This warning has been questioned by some, because it arose from studies with methodological errors49,50 and because the attempts of other researchers to repeat these findings have given contradictory results.51,52 In addition, it should be taken into account that symptoms such as fatigue, sleep disorders, weight gain and memory disturbances are common side effects of antiepileptic drugs and may be confused with symptoms of depression.53

With regard to surgical treatment for epilepsy, episodes of depression and anxiety are common in the postoperative period of these patients, particularly in the first three to six months after anterior temporal lobectomies. Depression has been reported in 20–40% of these patients. Although the majority of these depression disorders tend to recede at the end of the first year, they may persist in 10–15% of patients.54,55

Burden of diseaseEpilepsy represents a state of chronic stress and of increased allostatic load according to the diathesis-stress model.56 The “burden” related to this disease is configured from multiple factors: lesions related to the seizures,57 interictal and postictal fatigue,58 cognitive impairment, lower academic and socio-economic achievements,59 psychological stress60 and insomnia.61 Social stigma and lack of information in the community on this disease represent a specific additional burden for people with epilepsy.62,63 Therefore, it is not surprising that these patients have a particularly affected quality of life64,65 and that depression acts as one of the main predictive factors of this deterioration.66,67

Learned helplessness and attributional styleEpilepsy, as it is a chronic disease, generates significant burdens of stress of biological, psychological and social origin. Furthermore, depression is influenced by negative cognitive patterns that generate the tendency to react helplessly to difficulties and losses. Attributional style is the way in which a person explains things which occur to him/her in daily life. Hermann et al. demonstrated 20 years ago that attributional style is significantly associated with depression reported by the patient.68 Recurrent and unpredictable seizures favour the learned helplessness of people with epilepsy which, added to a negative attributional style, would be a fertile ground, from a cognitive point of view, for the onset of depression.69–71

Neurobiological factors in depression and epilepsyOne of the characteristics that both disorders have in common is the deregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.72,73 Epileptogenesis could be exacerbated with an excess of hormones released during the chronic states of stress that characterise depression, whilst the hippocampus is particularly vulnerable to these hormones due to the large quantities of corticosteroid receptors that it possesses.74 In a complementary manner, stress is the precipitant most commonly identified by people with epilepsy.75 Both corticoliberin and corticosteroids increase excitability of the neurons in the hippocampus and facilitate the start of seizures.76 In addition, a loss of bilateral cortical volume has been documented at the frontal level and in the left thalamus in people with epilepsy and depression.77

Another of the common mechanisms proposed is related to the production of granule cells in the hippocampus.78 Chronic stress, depression and epilepsy are associated with altered neurogenesis processes in adults.79 In depression and chronic stress, neurogenesis is reduced in the hippocampus; in epilepsy, although in early phases of the disease there is an aberrant integration of granule cells, in the late phase a reduction in cell production is observed. This alteration in granule cells would lead to the dentate gyrus not being able to prevent the excess of excitatory activity, which would enhance ictal activity. Furthermore, studies in mice have found that the lack of physical activity, common in patients with depression, leads to a reduction in the production of galanin, with the consequent increase in ictal activity.5

The role of glutamate in the pathogenesis of epilepsy is clear and has been recognised for a long time, and in recent years there has been talk of the role of this excitatory neurotransmitter in depression through a dysfunction of the transporter proteins and abnormal cortical levels of the neurotransmitter.39

Although these pathophysiological mechanisms link depression and epilepsy and signal a possible bidirectional relationship, it is necessary to verify these hypotheses rigorously through more studies and better methodology, which make it possible to prospectively explore the type of relationship that is established between these two clinical entities, to determine if it is possible to talk about a causal relationship and the possible modifying factors of the effect.

Antiepileptic drugs and depressionAntiepileptic drugs are the cornerstone of epilepsy treatment. According to some researchers, these “beneficial” effects should be contrasted with the behaviour and psychiatric problems that they may generate. Psychopathology in epilepsy has a multifactorial aetiology and antiepileptic drugs are only one of these aetiologies, which is why it is difficult to establish when the affective symptoms are secondary to the medication or are explained by other factors.80 Some antiepileptic drugs have been associated with depression symptoms and a greater risk of suicide, which resulted in the warning established by the FDA for all antiepileptic drugs.43,44

Some drugs such as phenobarbital, tiagabine, topiramate and vigabatrin have been associated with depression symptoms,81,82 an effect that is enhanced when the patient has a personal or family history of depression.83 With regard to levetiracetam, both negative and positive effects on the behaviour and affection of patients with epilepsy have been demonstrated.84,85 Furthermore, it is considered that carbamazepine, gabapentin, lacosamide, lamotrigine, pregabalin and sodium valproate have a better psychotropic profile.86,87 The dose, mode of release of the drug and family history of psychiatric disorders are determinants in the adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs.88

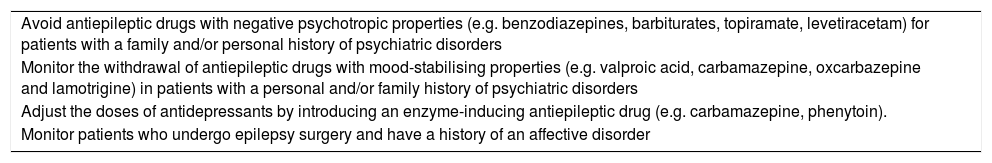

Treatment of depression in people with epilepsyThe goal of any treatment of depressive disorders of people with epilepsy is to achieve a complete remission of depression symptoms. Therapeutic strategies are both pharmacological and non-pharmacological. However, there are few controlled studies on the treatment of depression in people with epilepsy published to date. Therefore, treatment strategies for this population continue to be backed up by data derived from the treatment of primary depressive disorders.89 As iatrogenic depressive episodes are common in people with epilepsy, it is recommended to take some precautions to minimise or prevent their onset (Table 2).

Recommendations to prevent iatrogenic depressive episodes in people with epilepsy.28

| Avoid antiepileptic drugs with negative psychotropic properties (e.g. benzodiazepines, barbiturates, topiramate, levetiracetam) for patients with a family and/or personal history of psychiatric disorders |

| Monitor the withdrawal of antiepileptic drugs with mood-stabilising properties (e.g. valproic acid, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine and lamotrigine) in patients with a personal and/or family history of psychiatric disorders |

| Adjust the doses of antidepressants by introducing an enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drug (e.g. carbamazepine, phenytoin). |

| Monitor patients who undergo epilepsy surgery and have a history of an affective disorder |

Cognitive behavioural therapy has been effective in the treatment of depressive disorders in patients with and without epilepsy. This form of psychological therapy should be considered for patients who refuse to take antidepressants or who do not tolerate the adverse effects. Furthermore, it should be considered for people with epilepsy who have a long-term depressive disorder, particularly if they are associated with anxiety disorders.65

Pharmacological treatmentMost of the information published for the treatment of depressive disorders of people with epilepsy include uncontrolled clinical trials, with tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). To date, there have been few controlled studies which determine the effectiveness of antidepressants in people with epilepsy.

Two groups of experts have determined that SSRIs are the first line of treatment of the disorder due to their safety and tolerability profile. However, there are limited controlled studies with these medicines in this population.90

A study by Kanner et al.57 found remission of the depression symptoms in 59% of epilepsy patients treated with sertraline in monotherapy.91 Hovorka et al. evaluated the efficacy of citalopram in 43 people with epilepsy and depression. After four weeks of treatment, patients had a reduction in the Hamilton Scale for Depression (HAMD) score from 21.5 to 14.5 (p < 0.001). At eight weeks, the HAMD score had gone down to 9.9 (p < 0.001) and 65% of the patients had obtained a response.92

Kuhn et al. evaluated the effect of citalopram, mirtazapine and reboxetine in 75 people with epilepsy and depression. Symptoms of depression receded in 21.2% of patients on treatment with citalopram, 14.8% of those treated with mirtazapine and 20.0% of those with reboxetine while 36% of the first group, 52% of the second group and 53% of the third group had a >50% reduction of symptoms.93 A recently published study has suggested that glutamatergic and serotonergic modulation would be important objectives in the treatment of depression in epilepsy patients and that indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase inhibitors and norepinephrine activity enhancers could be administered along with valproic acid.94

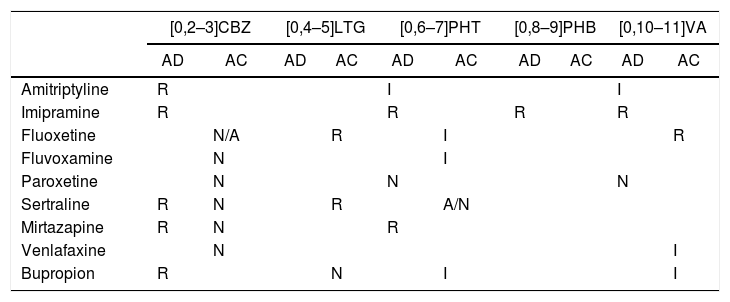

How do you choose an antidepressant for epilepsy patients?Some experimental studies have shown that antidepressants may modify the effects of antiepileptic drugs in three ways: increasing the anticonvulsant activity, leaving it the same or reducing it.95 Although such pharmacodynamic interactions and pharmacokinetic mechanisms may seem different from the clinical reality and the everyday life of patients, they have been proposed as key factors in the prognosis. Therefore, avoiding the use of antidepressants which reduce the seizure threshold and the efficacy of anticonvulsant drugs is a recommended medical practice (Table 3).

Interactions between antidepressants and anticonvulsants.

| [0,2–3]CBZ | [0,4–5]LTG | [0,6–7]PHT | [0,8–9]PHB | [0,10–11]VA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | AC | AD | AC | AD | AC | AD | AC | AD | AC | |

| Amitriptyline | R | I | I | |||||||

| Imipramine | R | R | R | R | ||||||

| Fluoxetine | N/A | R | I | R | ||||||

| Fluvoxamine | N | I | ||||||||

| Paroxetine | N | N | N | |||||||

| Sertraline | R | N | R | A/N | ||||||

| Mirtazapine | R | N | R | |||||||

| Venlafaxine | N | I | ||||||||

| Bupropion | R | N | I | I | ||||||

AC: anticonvulsant effect; AD: antidepressant effect; CBZ: carbamazepine; I: increases; LTG: lamotrigine; N: neutral; PHB: phenobarbital; PHT: phenytoin; R: reduces; VA: valproic acid. Adapted from Banach et al.89

In light of the scientific evidence presented, it is considered that depression is more than a simple comorbidity of epilepsy. Epidemiological studies confirm the existence of a bidirectional relationship between epilepsy and depression, which implies that it is not that epilepsy “causes” depression or vice-versa, but that such a relationship can be explained by the existence of common pathogenic mechanisms. Depression will precede the start of the seizure disorder in some cases and in others it will appear later on, but, regardless of the time at which they occur, they will have a negative impact on quality of life, prognosis of epilepsy, overall functioning of patients and their life expectancy.

It is therefore proposed that, at the time of the epilepsy diagnosis, a complete psychiatric assessment is carried out. This makes it possible to appropriately identify the personal and family psychopathological history of the patient, in addition to exploring the presence of affective symptoms and defining if psychotherapy and/or pharmacotherapy is required.

At the time of choosing anticonvulsants or antidepressants, drugs with an appropriate profile for epilepsy and depression should be chosen and, finally, depression should be systematically screened for (at least once a year) and when there are symptomatic (both seizure and emotional) relapses.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Zapata Barco AM, et al. Depresión en personas con epilepsia. ¿Cuál es la conexión? Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2020;49:53–61.