One of the experiences that represent the biggest risk for any society is child abuse. Despite the consequences of this form of violence, it tends to be a hidden and little understood phenomenon. The reason why parents mistreat their children has been one of the issues that has raised the most interest in the investigation of this phenomenon.

ObjectiveTo determine how the history of child abuse in adults is related to abusive behaviour directed at their own children.

MethodologyA cross-sectional study, based on a source of secondary information. The study included sociodemographic variables, variables related to violent behaviours directed to other people, pro-social factors and the use of psychoactive substances. From this population, 2 groups were selected, parents who were abusive and parents who were not abusive towards their own children. In both groups the frequency of different factors that could explain the probability of abusive behaviour of the adults towards their children was evaluated. We analysed the association between aggressive behaviour against one's own children and having a history of child abuse. As a measure of association, the OR was used with its respective 95% confidence interval and p-value <.05.

Results187 adults were included, 63.1% were women. The median [IQR] age was 38 [24–52] years. The abusive behaviour of the parents towards their children was associated with: the female sex (OR=2.23; 95%CI, 1.13–4.40), partner's aggression (OR=3.28; 95%CI, 1.58–6.80), aggression towards other people outside the family (OR=2.66; 95%CI, 1.05–6.74), pro-social behaviour (OR=0.32; 95%CI, 0.14–0.73), and dysfunctional behavioural traits (OR=2.23; 95%CI, 1.11–4.52). There was no association with the history of child abuse (OR=1.54; 95%CI, 0.59–4.04).

ConclusionsThe history of abuse in the parents’ childhood was not associated with abusive behaviour towards their children. Other forms of partner's violence and non-family violence were associated, suggesting that child abuse in the study population was related to other expressions of family and social violence.

Una de las experiencias que representan mayor riesgo para el desarrollo de cualquier sociedad es el maltrato infantil. A pesar de las graves consecuencias que derivan de esta forma de violencia, tiende a ser un fenómeno oculto y poco comprendido. La razón que los padres maltraten a sus hijos es una de las cuestiones que mayor interés ha suscitado en la investigación de este fenómeno.

ObjetivoDeterminar cómo se relaciona el antecedente de maltrato en la niñez de los adultos con el comportamiento maltratador dirigido a sus propios hijos.

MétodosEstudio transversal, a partir de fuente de información secundaria. Se incluyeron variables sociodemográficas, relacionadas con comportamientos violentos dirigidos a otras personas, factores prosociales y el uso de sustancias psicoactivas. A partir de esta población, se seleccionaron 2 grupos, padres maltratadores y no maltratadores de sus propios hijos. En ambos grupos se evaluó la frecuencia de diferentes factores que pudieran explicar la probabilidad de comportamiento maltratador de los adultos hacia sus hijos. Se analizó la asociación entre el comportamiento agresivo contra los propios hijos y el hecho de tener el antecedente de haber sufrido maltrato en la niñez. Como medida de asociación, se utilizó la odds ratio (OR) con su respectivo intervalo de confianza del 95% (IC95%) y un umbral de significación p < 0,05.

ResultadosSe incluyó a 187 adultos; el 63,1% eran mujeres. La mediana [intervalo intercuartílico] de edad fue 38 [24–52] años. El comportamiento maltratador de los padres hacia sus hijos se asoció con: sexo femenino (OR = 2,23; IC95%, 1,13–4,40), agresión a la pareja (OR = 3,28; IC95%, 1,58–6,80), agresión a otras personas fuera de la familia (OR = 2,66; IC95%, 1,05–6,74), comportamiento prosocial (OR=0,32; IC95%, 0,14-0,73) y rasgos de conducta disfuncionales (OR=2,23; IC95%, 1,11-4,52). No se encontró asociación con el antecedente de maltrato infantil en la niñez (OR=1,54; IC95%, 0,59-4,04).

ConclusionesEl antecedente de los padres de maltrato en la niñez no se asoció con el comportamiento maltratador hacia sus hijos. Sí se asociaron otras formas de violencia dirigida a la pareja y agresión a personas no familiares, lo que indica que el maltrato de la niñez en la población estudiada se relaciona con otras expresiones de violencia familiar y social.

Child abuse is a significant problem, with serious physical and psychological consequences for victims and enormous costs for society.1 It is one of the many forms of violence against children, which violates their fundamental rights.2 The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines it as the abuses and neglect to which children under the age of 18 are subjected, including “all forms of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect or negligent treatment or commercial or other exploitation, resulting in actual or potential harm to the child's health, survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust or power”.3 The worldwide frequency and severity of child abuse is not known.4 The global prevalence ranges from 2 to 62%5,6 and around 80% of abuse is perpetrated by parents or carers.7,8

In Colombia, the national rate of child abuse in 2014 was 67.14 cases/100,000 inhabitants. The most common cause of aggression was intolerance (87.6%); blunt trauma is the most common mechanism (73.3% of times) and multiple traumas occur in 54.4% of cases.9

A range of theories and models have been developed to explain the occurrence of intra-family abuse. The ecological model is most widely accepted, and considers that child abuse is the product of numerous factors, such as the characteristics of the child, the family, the carer or perpetrator of the abuse and the cultural, economic and social environment in which the family is situated.10 Since the 1960s, it has been proposed that early victimisation is a risk factor, potentially a causal one, for childhood victims of abuse to grow up and become abusive and negligent parents towards their own children.11

Although the intergenerational continuity of child abuse has been described in 7–60% of cases,10,12 studies show inconclusive results.13 The longitudinal Rochester Youth Development Study found that victims of child abuse were 2.6 times more likely to abuse their own children than those who had not been abused as children.14 However, Renner et al.15 found a weak association for the intergenerational transmission of child abuse, and some authors question the methodological quality of studies that support this mechanism of transmission of said maltreatment.16

Among the factors associated with the intergenerational transmission of child abuse, mental health problems in the mother or partner, partner violence, mothers with limited social support and financial difficulties have been described.12

Therefore, despite the availability of scientific evidence that implicates the intergenerational transmission of child abuse, this is insufficient and inconclusive regarding the problem; moreover, in Colombia, studies on the topic are few and far between. We have thus carried out this research with the aim of determining how a history of abuse in childhood among adults is related to abusive behaviour towards their own children.

MethodsA cross-sectional study was conducted with a secondary information source corresponding to the database of the study “Violence: Behaviours and associated factors. Itagüí, 2012–2013”. The reference population comprised the 258,520 inhabitants who, according to the National Administrative Department of Statistics (Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística; DANE), lived in the city of Itagüí in 2013.

The sample design of the primary study was calculated with a population size estimation formula, with a 95% confidence level, 5% precision and an estimated prevalence of 15.5% (prevalence in the last year of victims under threat in the city of Itagüí, according to results from the study “Violence in the Aburrá Valley, its magnitude and programme to reduce it 2004”). The chosen design was probabilistic and multi-stage, selected using the sampling framework that comprised all homes on different socio-economic strata within the six boroughs (urban area) and one township (rural area) of the city of Itagüí.

The study population included 187 adults selected from among the 486 who participated in the primary study. The selection criteria for respondents were having children and being aged between 19 and 65 at the time of the survey. The exclusion criteria determined were incomplete records regarding study variables or information of low-quality. Two groups were selected from this population, one comprising abusive parents (adults who showed abusive behaviour towards their own children) and the other non-abusive parents (adults who did not behave in this way). The frequency of various factors that might explain the likelihood of adults behaving abusively towards their children was assessed in both groups.

Mothers and fathers were deemed abusive if they answered yes to any of the following questions regarding their children in the past month: “have you: shouted at them? smacked their buttocks? hit them with an object somewhere other than the buttocks?”.17

The factors analysed were: sociodemographic (age, gender, level of education, area of residence, marital status, overpopulation, employment); related to violent behaviour (child abuse, violence towards children, partner violence, violence towards people outside the family); related to violent attitudes (irritability, behaviour disorder, attitudes of approval towards violence); related to psychoactive substance use (alcohol, marijuana, cocaine); and other factors associated with violence (family cohesion, prosocial behaviour, satisfaction scale, family support network).

The aforementioned variables form part of the following scales, which were validated by Torres et al.,16 and have appropriate psychometric properties:

- •

Family support network: explores the perception and specific everyday life situations in which a person feels supported by their family. This is an eight-item scale with a maximum score of 32. A score ≥21 was considered a good family support network.

- •

Satisfaction: explores how satisfied the individual is in all of the scenarios in which he/she interacts. It is an eight-item scale with a maximum score of 32. A value ≥26 was deemed the cut-off point for being satisfied.

- •

Prosocial behaviour: explores the empathetic behaviours the person may display in their everyday life. It is a nine-item scale with a maximum score of 18. A value ≥11 was deemed the cut-off point.

- •

Family cohesion: assesses the individual's perception on how their family interacts, shares and cooperates in all of life's scenarios. It is an eight-item scale with a maximum score of 36. A score ≥21 was established as good family cohesion.

- •

Attitudes of approval towards violence: explores the attitudes and beliefs a person may hold as regards how to resolve situations of conflict. It is a four-item scale with a maximum score of 20. A value ≥5 was deemed the cut-off point.

- •

Antisocial behaviour in childhood and adolescence: explores dysfunctional behaviour in childhood and adolescence. It consists of 13 yes/no response items. Any positive response was deemed the cut-off point.

- •

Irritability: assesses behaviours and attitudes related to irritability. It consists of 11 questions. A value ≥9 was deemed the cut-off point.

A descriptive analysis of all the sociodemographic, clinical and abuse-, violence- and victim-related variables was performed. The prevalence rates of abusive behaviour and violence in the study population were used as epidemiological indicators. Normality tests were performed and summary measures were calculated from the quantitative variables and absolute and relative frequency tables of the qualitative variables. The association between being an adult who abuses their children and the other study variables was investigated. The odds ratio (OR) was used as a measure of association, with its respective 95% confidence interval (95%CI). To establish the relationship between qualitative variables, the χ2 test of independence was used. The binary logistic regression model was used, in which the variables that met the Hosmer–Lemeshow criterion in the bivariate analysis were included (p<0.25). The age, education, home, marital status and employment variables were re-categorised, grouped into two categories for the multivariate model according to the clinical criteria of the investigating psychiatrists. To minimise potential bias, the database was managed by personnel trained in the field, thereby guaranteeing the reliability of the information obtained. Selection bias was controlled with probabilistic sampling; with the logistic regression model, it was also controlled by potential confounding variables. For the data analysis, the SPSS® software, version 21.0 (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL, USA), licensed to CES University, was used. The research was classified as risk-free according to Article 11 of Resolution 008430 of 1993. The primary study asked the participants for their informed consent and was approved by the CES University Ethics Committee. The information analysed was kept confidential at all times.

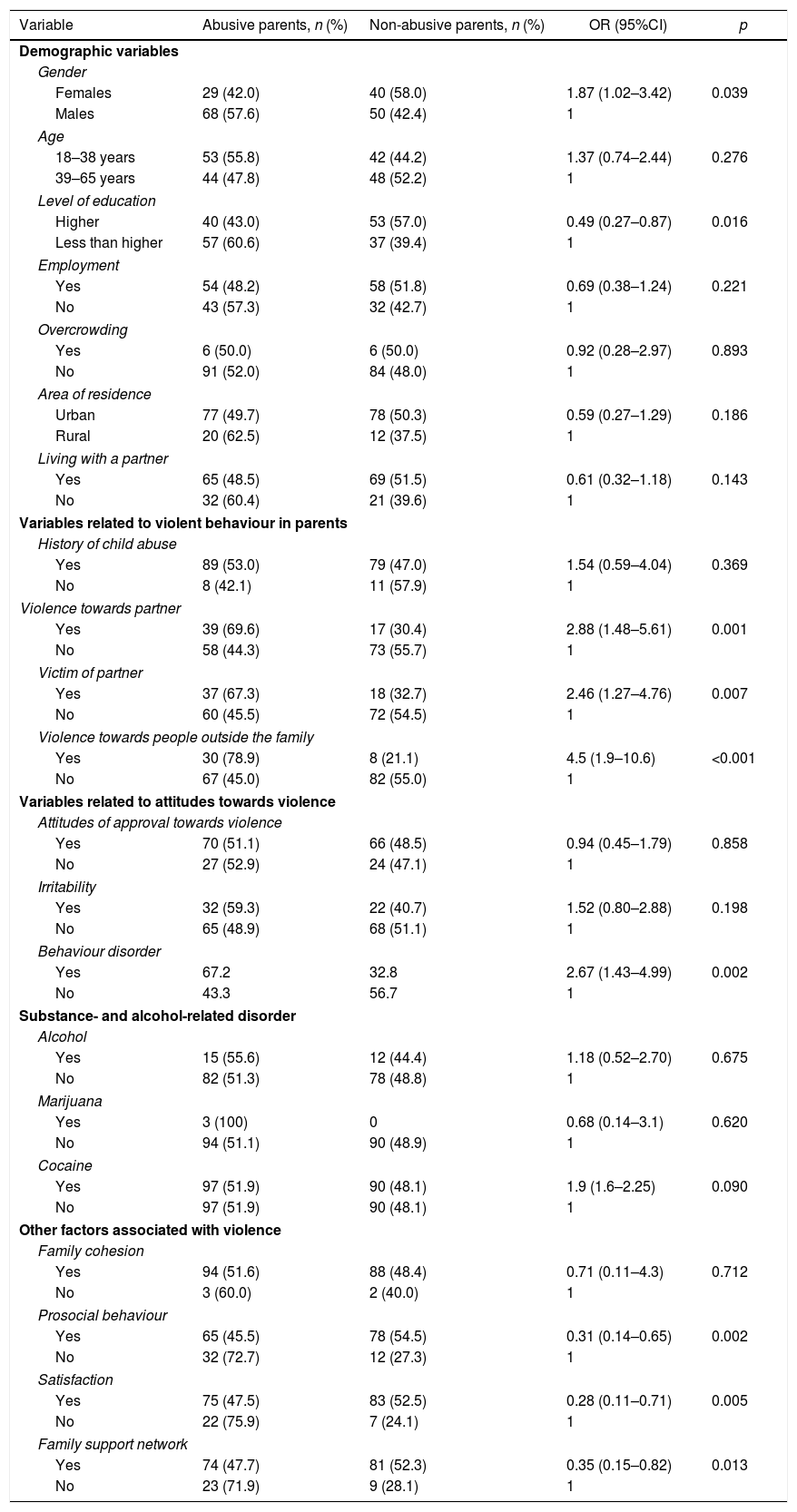

ResultsFor the analysis, the 187 adults from whom all the information on the study variables had been obtained were included. Of the total number of respondents, 63.1% were female, the median [interquartile range] age of the population was 38 [24–52] years, and the minimum and maximum ages, 18 and 62 years (Table 1).

Factors associated with parents’ aggressive behaviour towards their children. Adult population of the city of Itagüí, 2013.

| Variable | Abusive parents, n (%) | Non-abusive parents, n (%) | OR (95%CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Females | 29 (42.0) | 40 (58.0) | 1.87 (1.02–3.42) | 0.039 |

| Males | 68 (57.6) | 50 (42.4) | 1 | |

| Age | ||||

| 18–38 years | 53 (55.8) | 42 (44.2) | 1.37 (0.74–2.44) | 0.276 |

| 39–65 years | 44 (47.8) | 48 (52.2) | 1 | |

| Level of education | ||||

| Higher | 40 (43.0) | 53 (57.0) | 0.49 (0.27–0.87) | 0.016 |

| Less than higher | 57 (60.6) | 37 (39.4) | 1 | |

| Employment | ||||

| Yes | 54 (48.2) | 58 (51.8) | 0.69 (0.38–1.24) | 0.221 |

| No | 43 (57.3) | 32 (42.7) | 1 | |

| Overcrowding | ||||

| Yes | 6 (50.0) | 6 (50.0) | 0.92 (0.28–2.97) | 0.893 |

| No | 91 (52.0) | 84 (48.0) | 1 | |

| Area of residence | ||||

| Urban | 77 (49.7) | 78 (50.3) | 0.59 (0.27–1.29) | 0.186 |

| Rural | 20 (62.5) | 12 (37.5) | 1 | |

| Living with a partner | ||||

| Yes | 65 (48.5) | 69 (51.5) | 0.61 (0.32–1.18) | 0.143 |

| No | 32 (60.4) | 21 (39.6) | 1 | |

| Variables related to violent behaviour in parents | ||||

| History of child abuse | ||||

| Yes | 89 (53.0) | 79 (47.0) | 1.54 (0.59–4.04) | 0.369 |

| No | 8 (42.1) | 11 (57.9) | 1 | |

| Violence towards partner | ||||

| Yes | 39 (69.6) | 17 (30.4) | 2.88 (1.48–5.61) | 0.001 |

| No | 58 (44.3) | 73 (55.7) | 1 | |

| Victim of partner | ||||

| Yes | 37 (67.3) | 18 (32.7) | 2.46 (1.27–4.76) | 0.007 |

| No | 60 (45.5) | 72 (54.5) | 1 | |

| Violence towards people outside the family | ||||

| Yes | 30 (78.9) | 8 (21.1) | 4.5 (1.9–10.6) | <0.001 |

| No | 67 (45.0) | 82 (55.0) | 1 | |

| Variables related to attitudes towards violence | ||||

| Attitudes of approval towards violence | ||||

| Yes | 70 (51.1) | 66 (48.5) | 0.94 (0.45–1.79) | 0.858 |

| No | 27 (52.9) | 24 (47.1) | 1 | |

| Irritability | ||||

| Yes | 32 (59.3) | 22 (40.7) | 1.52 (0.80–2.88) | 0.198 |

| No | 65 (48.9) | 68 (51.1) | 1 | |

| Behaviour disorder | ||||

| Yes | 67.2 | 32.8 | 2.67 (1.43–4.99) | 0.002 |

| No | 43.3 | 56.7 | 1 | |

| Substance- and alcohol-related disorder | ||||

| Alcohol | ||||

| Yes | 15 (55.6) | 12 (44.4) | 1.18 (0.52–2.70) | 0.675 |

| No | 82 (51.3) | 78 (48.8) | 1 | |

| Marijuana | ||||

| Yes | 3 (100) | 0 | 0.68 (0.14–3.1) | 0.620 |

| No | 94 (51.1) | 90 (48.9) | 1 | |

| Cocaine | ||||

| Yes | 97 (51.9) | 90 (48.1) | 1.9 (1.6–2.25) | 0.090 |

| No | 97 (51.9) | 90 (48.1) | 1 | |

| Other factors associated with violence | ||||

| Family cohesion | ||||

| Yes | 94 (51.6) | 88 (48.4) | 0.71 (0.11–4.3) | 0.712 |

| No | 3 (60.0) | 2 (40.0) | 1 | |

| Prosocial behaviour | ||||

| Yes | 65 (45.5) | 78 (54.5) | 0.31 (0.14–0.65) | 0.002 |

| No | 32 (72.7) | 12 (27.3) | 1 | |

| Satisfaction | ||||

| Yes | 75 (47.5) | 83 (52.5) | 0.28 (0.11–0.71) | 0.005 |

| No | 22 (75.9) | 7 (24.1) | 1 | |

| Family support network | ||||

| Yes | 74 (47.7) | 81 (52.3) | 0.35 (0.15–0.82) | 0.013 |

| No | 23 (71.9) | 9 (28.1) | 1 | |

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

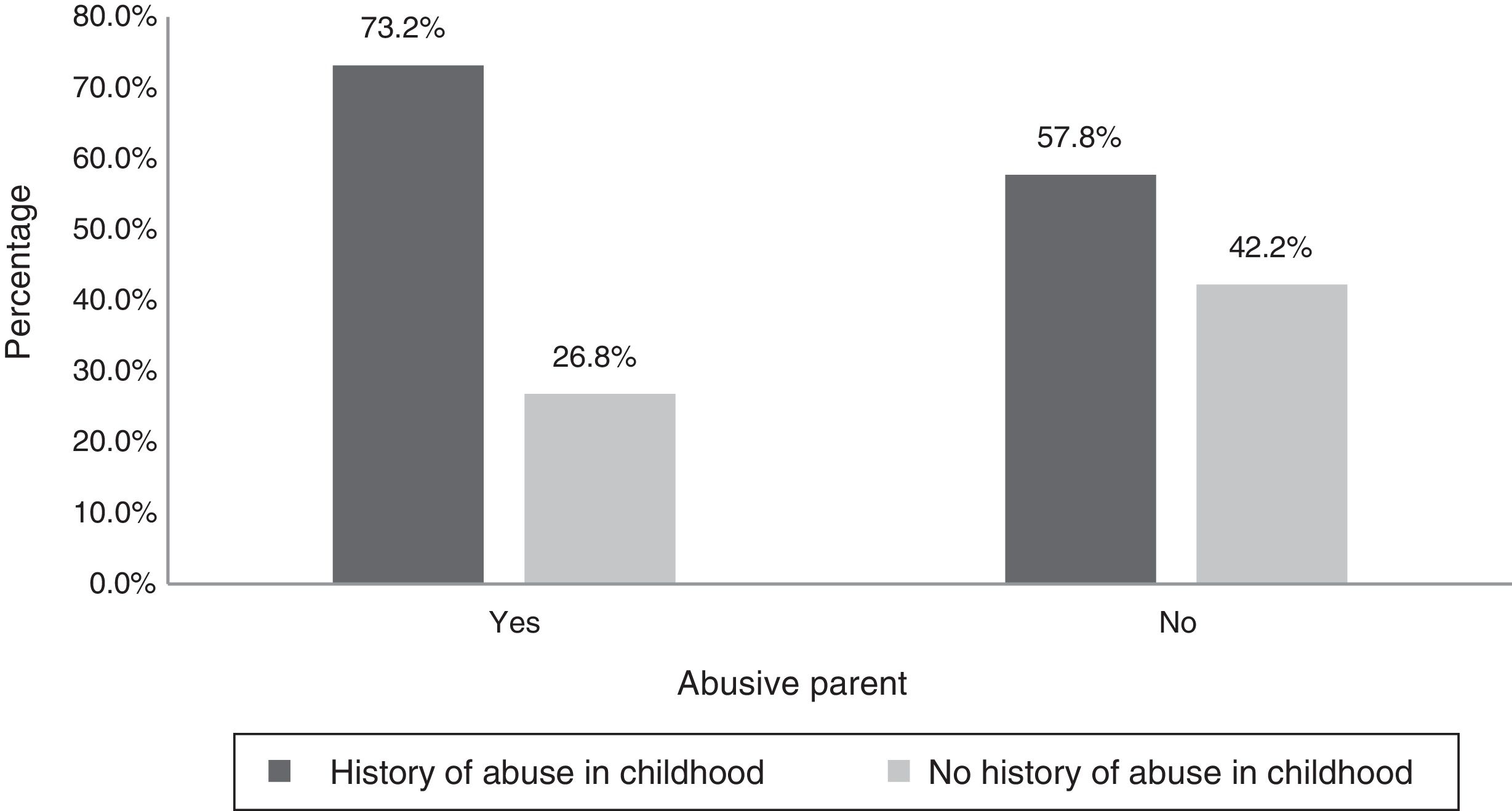

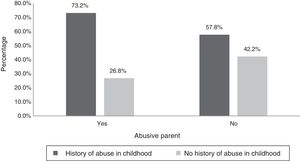

Of the total number of respondents, 51.9% were found to be abusive. Of these, 57.6% were female. The mother/father abuser ratio was 2.3:1. Among the abusive adults, 73.2% had a history of abuse in childhood (Fig. 1).

Variables related to violent behaviourOf the people with a history of abuse in childhood, 57.7% were abusive parents. A total of 69.6% of respondents who assaulted their partners were abusive parents and 78.9% of those who reported being victims of their partners also maltreated their children.

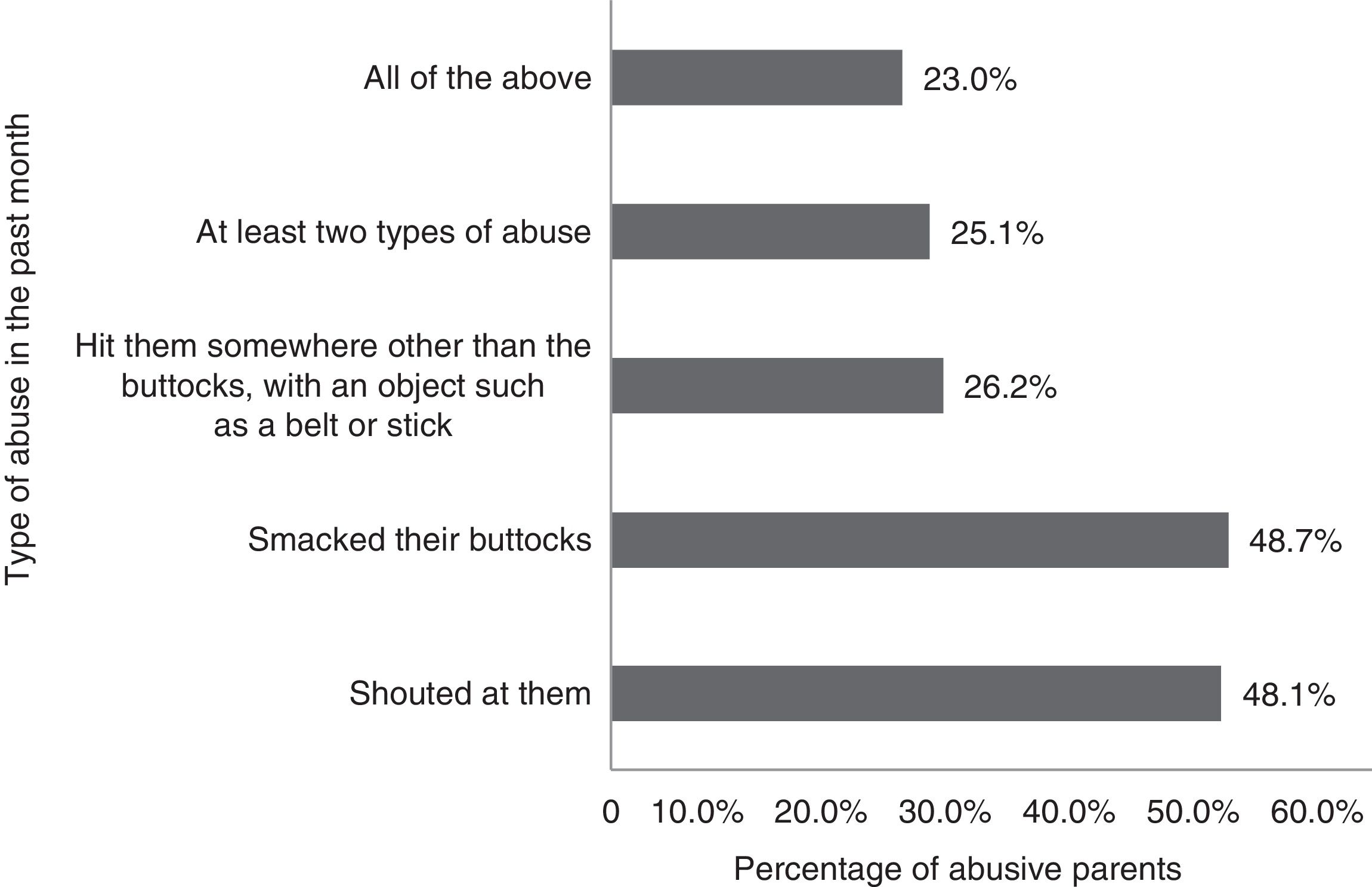

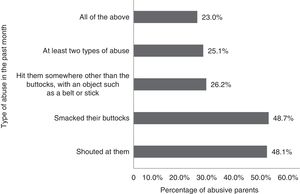

Types of abuseOf the types of abuse studied, it was observed that 26.2% hit their child somewhere other than the buttocks, with an object such as a belt or stick; 25.1% answered that they had committed two forms of abuse, and 23.0%, all three (Fig. 2).

Variables related to favourable attitudes towards violenceA total of 51.5% of those who had beliefs or attitudes about safety and the meaning of owning weapons and their right to take justice into their own hands were abusive parents, and of these, 73.2% had a history of abuse in childhood.

Psychoactive substance useA total of 52.1% of the abusive parents had consumed alcohol in the last month, versus 47.9% of the non-abusive parents. Of the abusive parents, 3.0% had used marijuana in the last month, versus none of the non-abusive parents. None of the parents reported cocaine use.

Social and familial factorsOf the individuals with “poor” family cohesion, 51.6% were abusive adults. The percentage of people with “limited” prosocial behaviour who behaved aggressively towards their children was 45.5%. On the personal satisfaction scale, it was observed that 47.5% of the “very unsatisfied” parents were abusive. As regards the family support network scale, 47.7% of people “without support” were abusive parents. In relation to the parents’ self-esteem, 51.9% of those who rated theirs as “poor” were abusive. Of the number of respondents who reported “poor” communication with their own mother or father, 52.2% abused their children.

Factors associated with parents’ aggressive behaviour towards their childrenIn the bivariate analysis, an association was found between the female gender, being a victim of partner violence, being a perpetrator of partner violence, violence towards people outside the family, dysfunctional behaviour traits and a history of abuse in childhood. Prosocial behaviour, having a family support network, having high personal satisfaction and having a higher level of education were found to be protective factors. Therefore, the probability of people who assault non-family members displaying violent behaviour towards their children was 4.5 times greater than in those who do not perpetrate these forms of violence. This factor had the strongest association in the bivariate analysis (Table 1).

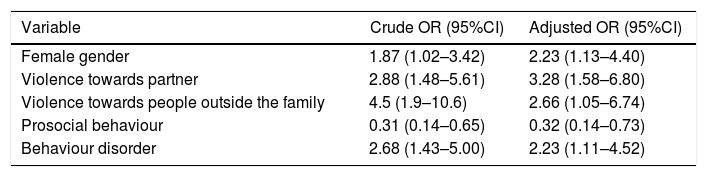

In order to control the effect of potential confounding variables, binary logistic regression was performed to analyse the association between parents who behave aggressively towards their children and candidate variables, which were selected due to having a p-value <0.25 in the bivariate analysis, according to the Hosmer–Lemeshow criterion. Independent variables that had more than two categories were analysed as dummy variables. The “Enter” method was later used to input the variables and obtain the adjusted measure. A statistical association was found with the female gender (OR=2.23; 95%CI, 1.13–4.40), partner violence (OR=3.28; 95%CI, 1.58–6.80), violence towards people outside the family (OR=2.66; 95%CI, 1.05–6.74), prosocial behaviour (OR=0.32; 95%CI, 0.14–0.73) and behaviour disorder (OR=2.23; 95%CI, 1.11–4.52) (Table 2).

Factors that explain the parents’ aggressive behaviour towards their children Itagüí adult population, 2013.

| Variable | Crude OR (95%CI) | Adjusted OR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 1.87 (1.02–3.42) | 2.23 (1.13–4.40) |

| Violence towards partner | 2.88 (1.48–5.61) | 3.28 (1.58–6.80) |

| Violence towards people outside the family | 4.5 (1.9–10.6) | 2.66 (1.05–6.74) |

| Prosocial behaviour | 0.31 (0.14–0.65) | 0.32 (0.14–0.73) |

| Behaviour disorder | 2.68 (1.43–5.00) | 2.23 (1.11–4.52) |

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

This study determined how a history of abuse in childhood among adults is related to abusive behaviour towards their own children. The main finding of the study was that said history was not significantly associated with being an abusive mother or father.

This finding coincides with the reports of other authors such as Widom,18 who used official data on the abuse of both parents and children and designed a cohort study with 908 confirmed child abuse victims aged 11 or younger, compared to 667 with no history of abuse. No statistical association was found between a history of abuse in childhood and being an abusive mother or father. Similarly, Altemeir et al.19 studied mothers who recalled abuse during childhood, and official agencies were consulted to check reports of their children having been abused in the past four years. In this case, no association was found for intergenerational abuse.

Although other studies have documented this association, some pose significant methodological problems, such as the disappearance of the effect when controlled by confounding variables,20 the samples selected were not representative of the general population,21 there was no comparison group,22 no clear definition of abuse was included,23 the measure of abuse came from hospital records and they were compared to the general population24 or abuse was assessed using public and private records referring to treatment for domestic violence.25,26

This study found that other forms of violence, such as partner violence and violence towards other people, were associated with parents abusing their own children. This may be related to the social and cultural norms that greatly contribute to child abuse due to justifying violence against children by accepting the efficacy of violent punishment in their upbringing.27

This study found that being female was a risk factor for child abuse. Generally, it has been shown that both sexes perpetrate child abuse, with no significant differences between them28; although there are various studies that have assessed the intergenerational transmission of abuse, these were only performed with female participants, which limits the scope for drawing conclusions.29,30 In Colombia, according to the 2015 intra-family violence report,31 mothers and fathers are the usual aggressors of children and adolescents (33.7% and 31.23%, respectively) followed by stepfathers (9.89%).

The five factors associated with child abuse in this study (female gender, partner violence, violence towards other people, antisocial behaviour and prosocial behaviour) account for 28% of the child abuse in the study population, which is significant, given the complexity of the phenomenon in question. These factors also indicate that child abuse in this population is not only confined to the family environment, but that it extends to the social domain, as highlighted by some researchers who list child abuse as another of the many forms of social violence.

The city of Itagüí, the place of origin of the study population, was one of the towns with the highest rates of violence in Colombia, particularly in the 1980s and 1990s.32 The study by Duque et al.27 on this population explored the factors associated with different types of violence, and found that a quarter of participants had histories of abuse in childhood and were exposed to domestic violence. Moreover, 37.1% of males and 34.7% of females felt physical punishment was needed in order to teach their children how to behave; 20% justified hitting their wives, 50% accepted illicit forms of moneymaking and a third of the population had relatives with a history of criminality or street violence. This raises the question as to whether the beliefs and attitudes of a community regarding violence lead to the generation of hetero-aggressive behaviours that include their children.

The study also found an association between the abuse of children and other people (partner and other non-family members), coinciding with other studies which have shown that poor intra-family relationships or violence among other family members are risk factors for child abuse.4,30

Prosocial behaviour was found to be a protective factor against child abuse in this population, indicating that if the individual has an attitude of empathy and collaboration towards others, there is a lower risk of the intergenerational transmission of abuse continuing, and reiterating the importance of quality relationships, not only with relatives but other people too.33,34 This protective factor has been widely reported in other studies and meta-analytical reviews.35

LimitationsThe results of this study are based on a survey, and may be influenced by possible memory biases. The history of abuse and abusive behaviour were determined using the same subject. Participants may not provide totally reliable information with regard to sensitive matters, such as those addressed in this survey. This study did not assess neglect as a significant and prevalent form of child abuse. The objective of the primary study's sample design was different to the present study, since it focused on estimating the population's overall risk of violent behaviour. No information was provided on the number of children of the mothers and fathers included in the study, meaning we are unable to verify whether this is an associated or confounding factor for the analysis. Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable information on child abuse in this population.

ConclusionsA history of abuse in childhood among parents was not associated with abusive behaviour towards their own children. Other forms of violence towards partners and non-family members were associated, however, indicating that child abuse in the study population was related to other expressions of family and social violence. Given the importance of this research problem both in order to understand human behaviour and to establish effective prevention measures, more studies are needed in order to understand the nature of this complex relationship.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors state that the procedures followed conformed to the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and to the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols implemented in their place of work regarding the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is in the possession of the corresponding author.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Ochoa O, Restrepo D, Salas-Zapata C, Sierra GM, Torres de Galvis Y. Relación entre antecedente de maltrato en la niñez y comportamiento maltratador hacia los hijos. Itagüí, Colombia, 2012–2013. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2019;48:17–25.