Suicidal behaviour is the cause of half of all violent deaths. It is considered to be a public health problem with one million victims a year. Suicide attempt is the most important risk factor. In Colombia, in 2017 the suicide attempt rate was 51.8/100,000 inhabitants, and the fatality rate reached 10.0/100,000. The objective is to identify suicide attempt factors associated with death and determine survival after the attempt for 2 years.

Material and methodsRetrospective cohort study and survival analysis. A total of 42,594 records of the suicide attempt surveillance system databases and 325 records of death by suicide in 2016 and 2017 were analysed. The risk factors were examined and a χ2-test and multivariate analysis and logistic regression were performed. Cumulative survival probability was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. A Cox regression model was applied to determine the proportional relationship of the suicide attempt variables that are related to suicide.

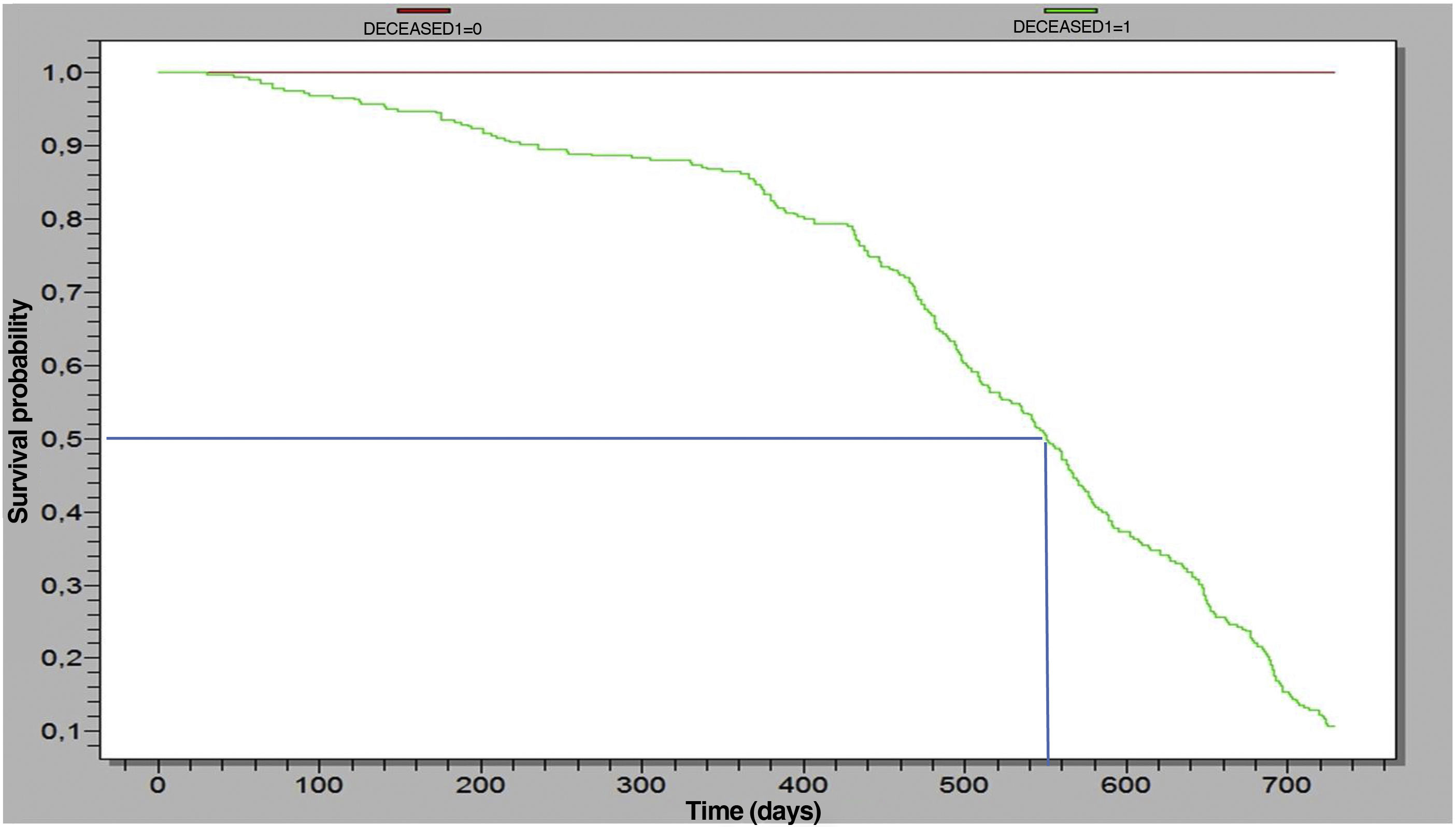

ResultsMen die by suicide 4.5 times more often than women. One in four suicide victims had made at least one prior suicide attempt. The attempt factors related with death by suicide were: male gender (HR = 2.99; 95% CI, 2.27−3.92), adulthood (over 29 years, HR = 2.38; 95% CI, 1.90−2.99), living in a rural area (HR = 2.56; 95% CI, 2.04−3.20), chronic disease history (HR = 2.43; 95% CI, 1.66−3.57) and depression disorder (HR = 1.94; 95% CI, 1.55−2.41). Some 50% of suicide deaths occur up to 560 days after the suicide attempt.

ConclusionsThe risk of suicide is highest in male patients, with a history of depression, chronic illness and exposure to heavy workloads.

La conducta suicida es la causa de la mitad de las muertes violentas. Se considera un problema de salud pública con un millón de víctimas al año. El intento de suicidio es el factor de riesgo más importante. En Colombia, en 2017 la tasa de intento de suicidio fue de 51,8/100.000 hab. y la letalidad alcanzó 10,0/100.000. El objetivo es identificar factores del intento suicida asociados con la muerte y determinar la supervivencia después del intento durante 2 años.

Material y métodosEstudio de cohorte retrospectiva y análisis de supervivencia. Se cruzaron 42.594 registros del sistema de vigilancia de intento de suicidio con 325 muertes por suicidio del registro único de defunciones de 2016 y 2017. Se examinaron factores de riesgo, y se realizó la prueba de la χ2, análisis multivariado y regresión logística. Se calculó la probabilidad de supervivencia acumulada con el método de Kaplan-Meier. Se aplicó un modelo de regresión de Cox para determinar la relación proporcional de las variables del intento suicida que se relacionan con suicidio.

ResultadosPor cada muerte de mujer por suicidio, mueren 4,5 varones por esta causa; 1 de cada 4 personas fallecidas reportó al menos un intento previo. Los factores del intento relacionados con la muerte por suicidio fueron: ser varón (HR = 2,99; IC95%, 2,27–3,92), la edad adulta (>29 años, HR = 2,38; IC95%, 1,90–2,99), vivir en área rural (HR = 2,56; IC95%, 2,04–3,20) y padecer enfermedad crónica (HR = 2,43; IC95%, 1,66–3,57) o trastorno depresivo (HR = 1,94; IC95%, 1,55–2,41). El 50% de las muertes por suicidio ocurren hasta en los 560 días posteriores al intento.

ConclusionesSe evidencia mayor riesgo de suicidio en pacientes varones, con historia de depresión, antecedentes de enfermedades crónicas y exposición a carga laboral.

Understanding the complexity of suicidal behaviour is crucially important for public health, mainly as it is the cause of almost half of all violent deaths, translating into almost 1 million victims per year.1 In addition to being a public health problem, attempted suicide is one of the most powerful and clinically relevant risk factors for suicide.1,2

The World Health Organisation (WHO) reported on its website that worldwide, about 16 in 100,000 people commit suicide (800,000) annually, exceeding the number of deaths from violence. For 2020, this figure was expected to have increased by 50%.3 For every person who commits suicide, there are another 20 who attempt it, making it the leading external cause of death in many countries around the world and one of the main causes of death for adolescents and people of productive age. As a consequence, suicides generate 2% of the global burden of disease.2

In Colombia, the suicide attempt rate has been increasing in the last 10 years, having risen from 0.9/100,000 population in 2009 to 37.7/100,000 in 2016 (mental health bulletin and final event report); the population most at risk is between the ages of 16 and 21.4 The 2015 National Mental Health Survey reported that the number of cases related to suicidal ideation is the same in adolescents and adults and suicide attempts are more common in women than in men.5 Colombia's suicide surveillance system registered an increase of 7270 (39%) cases of attempted suicide from 2016 to 2017.

The risk of suicide after a failed attempt has been estimated to be around 10% in studies with follow-up periods of five to 35 years. Being male, advanced age in women, having a psychiatric disorder and greater intention are risk factors for committing suicide; furthermore, most suicide attempts are related to physical self-harm or poisoning, both sometimes classified as non-violent.6

Predicting suicidal behaviour is often based on identifying short- and long-term risk factors. Suicide attempt is considered a clinically relevant predictor of suicidal behaviour,7 as this population has a 40- to 66-fold greater risk of suicide than the general population.8,9 However, there is confusion and debate about the importance in suicide of mild and severe suicide intent or attempts. This issue requires resolution, as ignoring risk factors associated with the intention to self-harm may hinder the identification of specific suicide risk factors.

Studies carried out in the war veteran population in the United Kingdom and northern Europe reported that the risk of suicide after the attempt is 5%–10% in follow-up periods of five to 35 years. The survival rate over 10 years of follow-up was 78%.10 A study carried out in Ontario from 2002 to 2011 in a population hospitalised for suicide attempts by poisoning identified a mean time of completed suicide during the observation period of 585 days.11

Another study carried out in Brazil with people who attempted suicide from 2003 to 2009 identified that, of 807 people who attempted suicide, 12 completed suicide in the 24 months following the attempt; the survival rate over the observation period was 62.5% for those aged over 60 and 87.9% for those under 60.12 This study aims to identify factors related to suicide deaths and estimate the survival rate from suicide attempts reported to Colombia's public health surveillance system over a two-year observation period.

MethodsWe performed a retrospective cohort study with survival analysis. We reviewed the databases of cases of suicide attempts in Colombia reported to the Sistema de Vigilancia en Salud Pública (Sivigila) [Public Health Surveillance System] and the databases of the single registry of deaths by suicide for the years 2016 and 2017.

The dependent variable of the study was suicide and the main independent variables were psychiatric history, family history of suicide and previous attempts. Other intervening independent variables were relationship, economic or work problems and chronic diseases. Lastly were the demographic variables age, gender, residential area and occupation.

For statistical analysis, death records (death by suicide) were identified and correspondence analysis was performed with the databases of notifications to Sivigila for suicide attempts retrospectively over a period of two years. A total of 42,917 cases were analysed.

We calculated frequencies, measures of central tendency and dispersion. Relationships were analysed based on the χ2 tests. Multivariate analysis and binary logistic regression were performed. A comparative analysis of sociodemographic variables was carried out for the suicide attempt and death by suicide records.

Cumulative survival probability was calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method. Follow-up time was defined as the number of days from the date of notification of the suicide attempt to the date of death by suicide. Cases with no information at the end of the follow-up period were considered censored data, and those recorded as death by suicide were considered uncensored.

A Cox regression model was applied to determine the variables proportionally related to death by suicide. We calculated 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and established a significance threshold at P = .05. The results are presented in tables and graphs.

Ethical considerationsThe study is considered risk-free based on Resolution 8430 of 1993 of the Colombian Ministry of Health. The information was obtained through the Sivigila databases and the single death registry. The principles of confidentiality of information and responsibility were taken into account. The results of this study will contribute to strengthening suicide attempt surveillance in the country and the world.

ResultsSuicide attemptIn 2016, in compliance with Law 1616 of 2013, the Colombian National Institute of Health began epidemiological surveillance of suicide attempts. Since surveillance began, the reported figures have increased by 46 points in five years; the suicide attempt rate went from 5.4/100,000 room in 2015 to 38.1 in 2016 and 51.8 in 2017. In the period 2016–2017, a total of 44,112 cases of attempted suicide were reported through Sivigila, 42% (18,577) corresponding to 2016 and 58% (25,535) to 2017, signifying a 37.5% increase in the number of cases. Overall, 0.9% were reported to the surveillance system as deceased.

In the same period, 63% of the reported events were committed by females and 37%, males. The female-to-male ratio in the period was 1.7; for every male who attempted suicide, approximately two women did so. In 48.7% of suicide attempts, the person was in the 15-to-24-year-old age group (29.6% aged 15–19 and 19.1% aged 20–24). According to ethnicity, 93.6% were reported as “others” (without defined ethnic identity); 3.5% were of African descent; 2.4% were indigenous population; 0.4% Roma (Gypsies); 0.1%, Raizal (Afro-Caribbean population of the Archipelago of San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina); and less than 0.1%, Palenquero. Nineteen of the cases (0.1%) were of foreign origin (4 in 2016 and 15 in 2017).

The highest number of cases by province of origin occurred in Antioquia, Valle, Bogotá, Cundinamarca, Nariño, Atlántico and Huila. In 2017, the highest suicide attempt rate in the country was in Caldas (94.7/100,000 population), followed by Putumayo (94.6), Huila (84.9), Quindío (82.4) and Arauca (81.7). The incidence (new cases reported as first suicide attempt) in 2016 was 26.5/100,000 population, while in 2017 it was 34.9, this value being associated with the notification of more cases without previous suicide attempts.

The main triggering factors for suicide attempts in the period 2016–2017 were relationship conflicts (39.3% in 2016 and 40.9% in 2017), legal problems (20.8% and 4,1%), the consumption of psychoactive substances (8.9% and 12.8%) and serious illness (2.7% and 5.1%). In 2017, additional factors were found, such as financial problems (11.5%), school problems (6.3%) and physical, psychological or sexual abuse (5.8%).

The most common psychiatric disorders related to suicide attempts during the period evaluated were depressive disorder, other affective disorders, psychoactive substance abuse and bipolar disorder.

During the period 2016–2017, the most used mechanisms for suicide attempts were poisoning (67.8% of cases), followed by sharp weapons (20.1%), hanging (5.4%) and jumping from height (2.9%). Other less common mechanisms were throwing oneself in the path of a moving vehicle, self-immolation or self-inflicted burns, and jumping into water.

It is important to mention that in 2016, 30.4% (5648) of the cases reported as attempted suicide had a history of previous attempts, while in 2017 this figure increased to 32.4% (8284). The average number of suicide attempts prior to the last notification to the system was 2.03 in 2016 and 1.9 in 2017.

SuicideAccording to mortality statistics recorded in 2016 and 2017, the number of deaths from suicide in Colombia was 3212, with annual averages of 1606 cases and monthly averages of 133. In November 2018, 1262 cases had been reported, with a monthly average of 115. In terms of suicide rates, an increase was found in the period evaluated from 4.7/100,000 population in 2016 to 5.03 in 2017. In 82% of suicide deaths, the person was male, with a male-to-female ratio of 4.5.

The distribution in 2016 and 2017 shows the age group where suicide was most common was 20-to-24-year-old (14.5% in 2016 and 14.8% in 2017), followed by 15–19 (13.3% and 12.3%) and 25–29 (11.6% and 12.1%).

The provinces that recorded the most cases of suicide were Antioquia, Bogotá, Valle, Cundinamarca and Santander. In 2017 Vaupés (20.2/100,000 population), Arauca (13.0) and Quindío (9.2) were the provinces with the highest mortality rate from suicide; in 2016, Guainía reported a rate of 9.5/100,000 population, higher than Quindío. In the period evaluated, 18 provinces were above the national rate in both years (4.7/100,000 population in 2016 and 5.03 in 2017).

In the period from 2016 to November 2018, the mechanisms most commonly used by patients were hanging (62.9%), poisoning (16.5%), firearm (11.8%) and jumping from height (4.9%). Drowning, burns and throwing oneself in the path of a moving vehicle were below 1%. In this same period, 30 cases were reported in which it was not possible to determine the mechanism that led to death.

Attempted suicide and suicideOf all cases of suicide as a cause of death reported from 2016 to November 2018 (n = 6054), 5.3% were part of the suicide attempt surveillance system reports. The fatality of attempted suicide, with respect to the population reported within the surveillance system, was 10.0/100,000 population in 2017, more than double that calculated in 2016 (3.6). Approximately one in four people who committed suicide had at least one previous suicide attempt recorded.

Of the suicides in the period evaluated 46.8% were by people aged 15–29. Only 12.9% of the suicides were by people over the age of 55. Contrary to what was found in attempted suicide, more males actually commit suicide (68.3%) than females (31.7%), with a male-to-female ratio of 2.1.

The methods used to commit suicide were poisoning (54.8%), suffocation or hanging (31.7%) and firearms (6.8%). The method chosen for suicide does not vary by sex. However, females use poisoning more (50% of males and 65% of females), while men are more likely to use suffocation or hanging and firearms.

The most common places of death were hospital or clinic (49.5%) and the person's home (37.2%). Deaths from poisoning cases occurred more often in a hospital (64.6%) and deaths from hanging, at their home (65%).

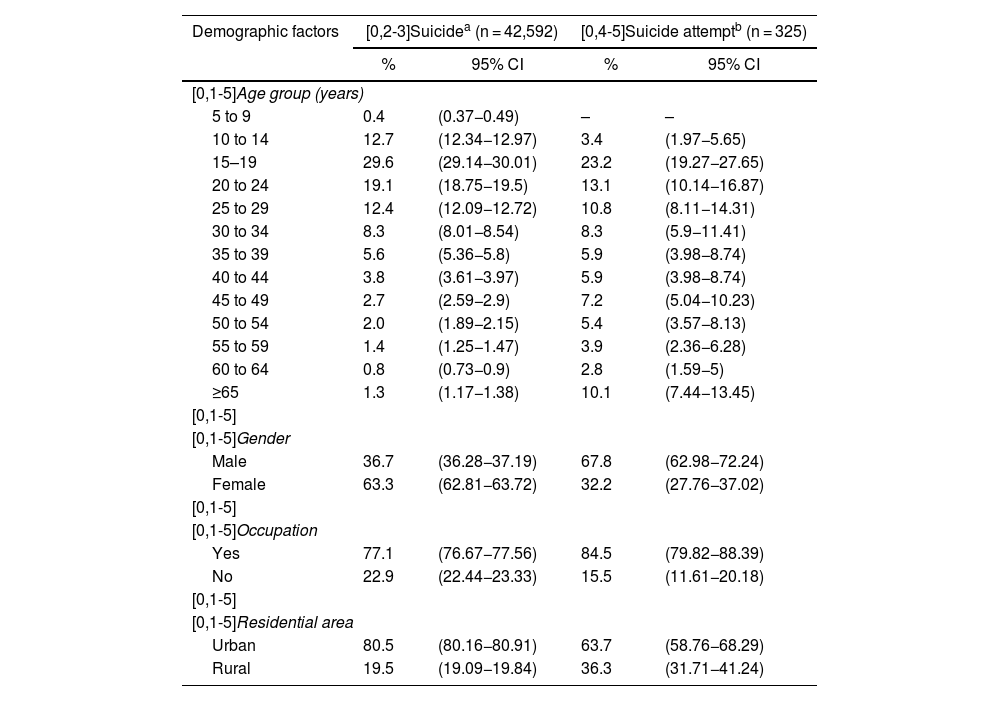

Comparison of factors associated with suicide and attempted suicideTable 1 compares the proportions of the demographic factors in the evaluated groups; both show high proportions in the ages of 15–29 years and the group of people with some form of occupation. In the distribution by gender, there were more females in the suicide attempt group and more males in the suicide group. According to place of residence, 80.5% of suicide attempts were by people living in urban areas, while only 60.3% lived in urban areas in the completed suicide group.

Distribution of demographic variables according to suicide attempt and suicide. Colombia, 2016-2017.

| Demographic factors | [0,2-3]Suicidea (n = 42,592) | [0,4-5]Suicide attemptb (n = 325) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| [0,1-5]Age group (years) | ||||

| 5 to 9 | 0.4 | (0.37−0.49) | – | – |

| 10 to 14 | 12.7 | (12.34−12.97) | 3.4 | (1.97−5.65) |

| 15–19 | 29.6 | (29.14−30.01) | 23.2 | (19.27−27.65) |

| 20 to 24 | 19.1 | (18.75−19.5) | 13.1 | (10.14−16.87) |

| 25 to 29 | 12.4 | (12.09−12.72) | 10.8 | (8.11−14.31) |

| 30 to 34 | 8.3 | (8.01−8.54) | 8.3 | (5.9−11.41) |

| 35 to 39 | 5.6 | (5.36−5.8) | 5.9 | (3.98−8.74) |

| 40 to 44 | 3.8 | (3.61−3.97) | 5.9 | (3.98−8.74) |

| 45 to 49 | 2.7 | (2.59−2.9) | 7.2 | (5.04−10.23) |

| 50 to 54 | 2.0 | (1.89−2.15) | 5.4 | (3.57−8.13) |

| 55 to 59 | 1.4 | (1.25−1.47) | 3.9 | (2.36−6.28) |

| 60 to 64 | 0.8 | (0.73−0.9) | 2.8 | (1.59−5) |

| ≥65 | 1.3 | (1.17−1.38) | 10.1 | (7.44−13.45) |

| [0,1-5] | ||||

| [0,1-5]Gender | ||||

| Male | 36.7 | (36.28−37.19) | 67.8 | (62.98−72.24) |

| Female | 63.3 | (62.81−63.72) | 32.2 | (27.76−37.02) |

| [0,1-5] | ||||

| [0,1-5]Occupation | ||||

| Yes | 77.1 | (76.67−77.56) | 84.5 | (79.82−88.39) |

| No | 22.9 | (22.44−23.33) | 15.5 | (11.61−20.18) |

| [0,1-5] | ||||

| [0,1-5]Residential area | ||||

| Urban | 80.5 | (80.16−80.91) | 63.7 | (58.76−68.29) |

| Rural | 19.5 | (19.09−19.84) | 36.3 | (31.71−41.24) |

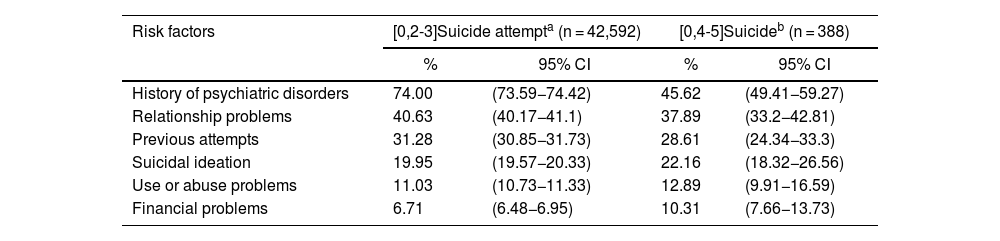

The notification form allows 16 different risk factors associated with suicide attempts to be recorded. The results of this study showed higher proportions for the history of psychiatric disorders risk factor in the suicide attempt group (70.29%) compared to the completed suicide group (44.07%). Apart from financial problems, which were more common in the suicide group, the other risk factors showed similar proportions in both groups. The risk factors not described had proportions <5% (Table 2).

Distribution of risk factors according to suicide attempt and suicide. Colombia, 2016–2017.

| Risk factors | [0,2-3]Suicide attempta (n = 42,592) | [0,4-5]Suicideb (n = 388) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| History of psychiatric disorders | 74.00 | (73.59−74.42) | 45.62 | (49.41−59.27) |

| Relationship problems | 40.63 | (40.17−41.1) | 37.89 | (33.2−42.81) |

| Previous attempts | 31.28 | (30.85−31.73) | 28.61 | (24.34−33.3) |

| Suicidal ideation | 19.95 | (19.57−20.33) | 22.16 | (18.32−26.56) |

| Use or abuse problems | 11.03 | (10.73−11.33) | 12.89 | (9.91−16.59) |

| Financial problems | 6.71 | (6.48−6.95) | 10.31 | (7.66−13.73) |

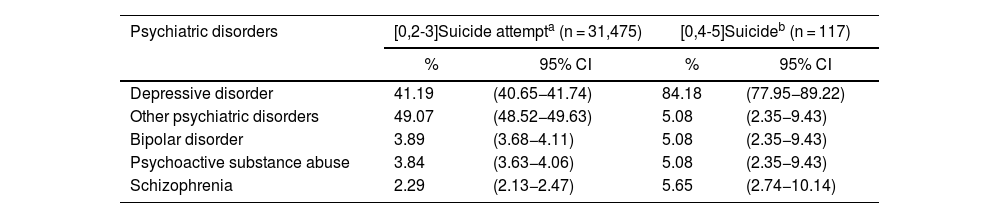

Of the psychiatric disorders, depressive disorder was representative (84.18% of suicide cases and 41.19% of attempts). The remaining disorders had values below 5%, except “other psychiatric disorders” in the suicide attempt group, where the frequency was 49.07% (Table 3).

Distribution of psychiatric history according to suicide attempt and suicide. Colombia, 2016–2017.

| Psychiatric disorders | [0,2-3]Suicide attempta (n = 31,475) | [0,4-5]Suicideb (n = 117) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| Depressive disorder | 41.19 | (40.65−41.74) | 84.18 | (77.95−89.22) |

| Other psychiatric disorders | 49.07 | (48.52−49.63) | 5.08 | (2.35−9.43) |

| Bipolar disorder | 3.89 | (3.68−4.11) | 5.08 | (2.35−9.43) |

| Psychoactive substance abuse | 3.84 | (3.63−4.06) | 5.08 | (2.35−9.43) |

| Schizophrenia | 2.29 | (2.13−2.47) | 5.65 | (2.74−10.14) |

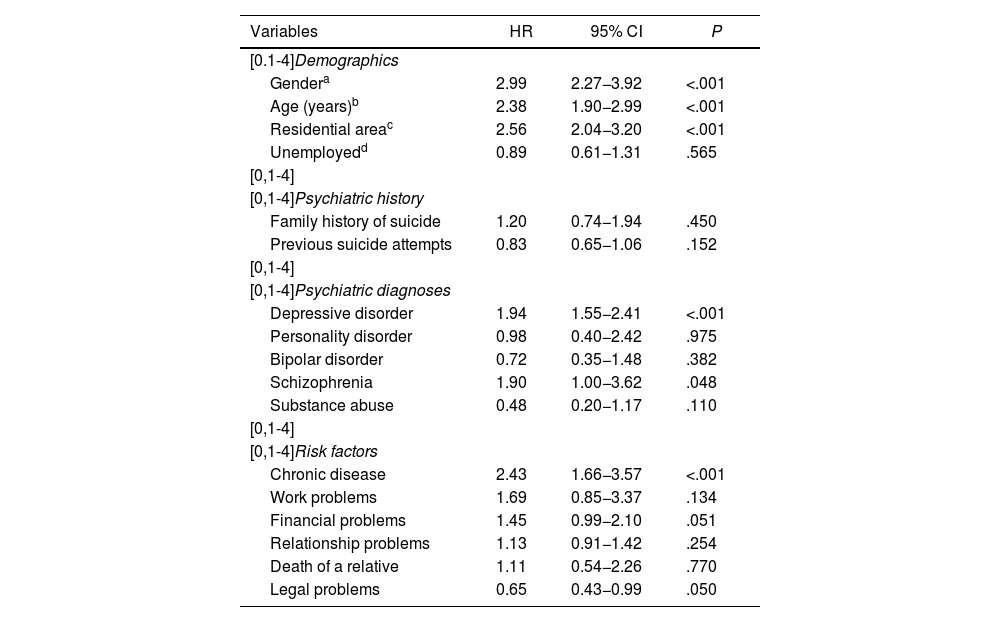

The results obtained with the multivariate analysis by binary regression indicated that being male (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.99; 95% CI, 2.27−3.92), age (>29 years, HR = 2.38; 95% CI, 1.90−2.99) and living in a rural area (HR = 2.56; 95% CI, 2.04−3.20) were significant suicide risk factors (Table 4).

Multivariate analysis of predictors of suicide attempt and suicide. Colombia, 2016–2017.

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| [0.1-4]Demographics | |||

| Gendera | 2.99 | 2.27−3.92 | <.001 |

| Age (years)b | 2.38 | 1.90−2.99 | <.001 |

| Residential areac | 2.56 | 2.04−3.20 | <.001 |

| Unemployedd | 0.89 | 0.61−1.31 | .565 |

| [0,1-4] | |||

| [0,1-4]Psychiatric history | |||

| Family history of suicide | 1.20 | 0.74−1.94 | .450 |

| Previous suicide attempts | 0.83 | 0.65−1.06 | .152 |

| [0,1-4] | |||

| [0,1-4]Psychiatric diagnoses | |||

| Depressive disorder | 1.94 | 1.55−2.41 | <.001 |

| Personality disorder | 0.98 | 0.40−2.42 | .975 |

| Bipolar disorder | 0.72 | 0.35−1.48 | .382 |

| Schizophrenia | 1.90 | 1.00−3.62 | .048 |

| Substance abuse | 0.48 | 0.20−1.17 | .110 |

| [0,1-4] | |||

| [0,1-4]Risk factors | |||

| Chronic disease | 2.43 | 1.66−3.57 | <.001 |

| Work problems | 1.69 | 0.85−3.37 | .134 |

| Financial problems | 1.45 | 0.99−2.10 | .051 |

| Relationship problems | 1.13 | 0.91−1.42 | .254 |

| Death of a relative | 1.11 | 0.54−2.26 | .770 |

| Legal problems | 0.65 | 0.43−0.99 | .050 |

Source: Database of suicide attempts from the Public Health Surveillance System, 2016 and 2017, and single registry of deaths by suicide, 2016 and 2017.

Review of the seven diagnoses reported on the reporting form showed that depressive disorder (HR = 1.94; 95% CI, 1.55−2.41) can be considered a risk factor associated with suicide. The other conditions did not obtain significant values. Of the additional risk factors reported through the surveillance system, chronic disease (HR = 2.43; 95% CI, 1.66−3.57) can be considered another risk factor for suicide (Table 4).

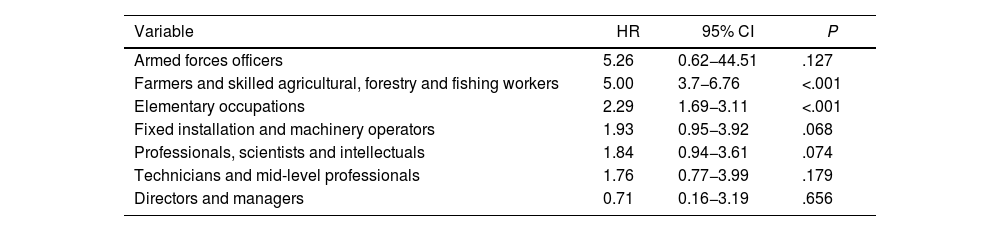

Regarding occupation, the different professions were grouped according to the occupation table to analyse their association with suicide. The results relating to jobs in agriculture and elementary occupations showed a higher risk of suicide compared to other occupations. Armed forces officers, operators of fixed installations and machinery, professionals and technicians had an HR > 1, but this value was not significant (P > .005) (Table 5).

Multivariate analysis of suicide attempt and suicide according to occupation*. Colombia, 2016–2017.

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Armed forces officers | 5.26 | 0.62−44.51 | .127 |

| Farmers and skilled agricultural, forestry and fishing workers | 5.00 | 3.7−6.76 | <.001 |

| Elementary occupations | 2.29 | 1.69−3.11 | <.001 |

| Fixed installation and machinery operators | 1.93 | 0.95−3.92 | .068 |

| Professionals, scientists and intellectuals | 1.84 | 0.94−3.61 | .074 |

| Technicians and mid-level professionals | 1.76 | 0.77−3.99 | .179 |

| Directors and managers | 0.71 | 0.16−3.19 | .656 |

Source: Database of suicide attempts from the Public Health Surveillance System, 2016 and 2017, and single registry of deaths by suicide, 2016 and 2017.

Of the 325 suicide deaths during the observation period, the median survival (0.5) from the suicide attempt was 560 days (1.5 years; P < .05). After that time, the likelihood of occurrence is lower (Fig. 1).

DiscussionThe decision to end one's life is perhaps the most important decision a person can make. However, suicidal thoughts are often private and undetectable until they are converted into a suicide attempt. Furthermore, it is difficult to really define risk factors that can predict which patients are potentially suicidal and whether there is a difference in the characteristics and risk factors between those who attempt suicide and those who actually commit suicide. This study has enabled us to identify risk factors associated with suicide on the basis of risk factors related to suicide attempts.

Our results show similarities between suicides and suicide attempts in terms of the proportion of cases in the age groups with the highest number of events, the method used to attempt or commit suicide, and risk factors such as relationship problems and previous attempts and history of mental illness. Regarding the lethality of suicide attempts, our results confirm the trend reported by other authors, in that there were significantly higher numbers of completed suicides by males than by females, while in general, cases of attempted suicide are predominantly female, with figures as much as four or five times higher than for males.13–15

Over the age of 45, only 8.2% of the sample had attempts at suicide, in line with the findings from other studies that the risk of attempted suicide decreases with age, because at older ages there is greater intention, more lethal methods are used and the probability of survival is lower, meaning that any attempts tend to be fatal.16,17 This could make it extremely important to be attentive to this type of patient.

In this study, the methods most used by males were asphyxiation, hanging and firearms, while females were more likely to choose poisoning. These finding are similar to those documented by another study in which there was a higher proportion of suicides by males, and it is also known that they choose more violent methods for committing suicide.18 Lethality could also therefore be related to the method chosen for suicide.19

In terms of demographic factors, it was found that males are at greater risk of dying by suicide. Males are vulnerable to some risk factors common to females, but, unlike in females, these factors are sometimes not exposed due to their sociocultural context.20 Studies have shown that stressful events in males are considered part of the masculine identity,21 which means that males use isolated coping strategies more than the help of healthcare systems.22,23 In addition to the above, males choose more violent means to commit suicide.24,25

Being over the age of 30 has a strong association with suicide. Data reported by the World Health Organisation show that suicide rates tend to increase according to age, for both males and females, until reaching a peak in old age26; some studies have also shown that the risk of suicide increases with age.27 Chronic illness was also found to be a risk factor for suicide. This is consistent with a study in which several common medical illnesses, such as congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and seizures are independently associated with an increased risk of suicide.28 That same study reported that intense pain not adequately treated and resulting from a chronic illness can also be a risk factor for suicide.

Other risk factors associated with suicide found in this study were living in rural areas and type of employment. Living in rural areas is closely associated with the difficulty in accessing health services and the ease of accessing firearms and lethal chemicals.29

Certain occupations have a higher risk of suicide than others. In our study, we found an association between suicide and elementary occupations, such as machinery operators, people performing cleaning services and agricultural workers. Work-related stress can be a big risk factor for suicide, especially when combined with poor social support,30 great psychological demands, little opportunity to make decisions and long working hours.31 In contrast to our study, other authors report that the highest risk of suicide is in police officers, detectives in public service, military personnel and medical staff. This is explained by their easy access to lethal weapons32 or, in the case of medical staff, harmful drugs.33

Psychiatric illnesses are risk factors for suicide. In line with other studies, we found a strong association between suicide and depression, signalling depression as one of the main risk factors for suicide, especially for young females and older people,27 and making continuous assessment of the risk of suicide in depressed patients essential.34

In this study, we did not find a statistically significant association between suicide and affective disorders, personality disorders, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or psychoactive substance use. Non-significant findings may reflect the difficulty in capturing such a complex phenomenon as psychiatric diagnoses, which can also depend on the clinical context, the informant or companion, and the person responsible for filling out the notification forms. However, the results indicate that these symptoms may be useful as risk factors for suicide attempt.

ConclusionsThe association between chronic diseases and suicide is a significant clinical problem, considering that these patients tend to have regular contact with health services, providing more opportunities to monitor and intervene. Depression is a key risk factor for suicide, with the advantage that it can be treated effectively, reducing the risk of both suicide attempts and actual suicide. Work stress and residential areas are important risk factors for suicide, which need further evaluation in patients who have attempted suicide.

Predicting suicide is a challenging task, and only by becoming more aware of risk factors and providing appropriate interventions when patients are identified as at high risk will we move towards reducing rates. Studying the survival rate analysis by occupation is important for the possible associated factors.

FundingThis study was funded by the Directorate for Public Health Surveillance and Risk Analysis of the National Institute of Health.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in this study.

We thank the Directorate for Public Health Surveillance and Risk Analysis for providing the information to conduct the study.

This paper was presented as a poster at the 10th TEPHINET Global Scientific Conference from 28 October to 1 November 2019.