Annual suicide rates are increasingly notably worldwide due to various accompanying risk factors. The objective of this study is to know the suicide mortality rates and their distribution between the years 2017 and 2019.

MethodsThe national death registries of the Ministry of Health of Peru were analysed, calculating the regional death rates from suicides adjusted for age and gender using the standardisation recommended by the World Health Organization.

ResultsA total of 1666 cases of suicide were identified (69.3% males); the age group with the highest frequency was that of 20–29 years (27.8%); the mean age at suicide was higher in males (37.49±18.96 vs. 27.86±15.42; P<.001). Hanging was the most common suicide method among both males (58.87%) and females (48.14%). For males, hanging was followed by poisoning (22.6%) and firearms (4.59%); for females, by poisoning (38.75%) and firearms (0.59%). The suicide rate increased from 2017 (1.44/100,000 inhabitants) to 2019 (1.95). The highest rates were identified in the departments of Arequipa, Moquegua and Tacna.

ConclusionsIn recent years, there has been an increase in the number of suicide cases and the rates by department, with the highest number of cases reported in males. Males tend to use more violent suicide methods. The risk factors in the vulnerable populations that were identified in this study need to be known.

Cada año, los casos de suicidio vienen en notable aumento en todo el mundo por diversos factores de riesgo. El objetivo de este estudio es conocer las tasas de mortalidad por suicidios y su distribución entre los años 2017 y 2019.

MétodosSe analizaron los registros nacionales del Sistema Nacional de defunciones del Ministerio de Salud del Perú. Se calcularon las tasas regionales de mortalidad por suicidios ajustadas por edad y sexo mediante la estandarización recomendada por la Organización Mundial de la Salud.

ResultadosSe identificaron 1.666 casos de suicidio (el 69,3% varones); el grupo etario con mayor frecuencia fue el de 20 a 29 años (27,8%); la media de edad al suicidio fue mayor en los varones (37,49±18,96 frente a 27,86±15,42; P<,001). El ahorcamiento fue el método de suicidio más prevalente entre los varones (58,87%) y las mujeres (48,14%). En el caso de los varones, los demás métodos fueron envenenamiento (22,6%) y armas de fuego (4,59%); en el de las mujeres, envenenamiento (38,75%) y uso de armas de fuego (0,59%). La tasa de suicidio aumento de 2017 (1,44 muertes/100.000 hab.) a 2019 (1,95). Las mayores tasas se identificaron en los departamentos de Arequipa, Moquegua y Tacna.

ConclusionesEn los últimos años ha habido un aumento en el número de casos de suicidio y en las tasas por departamento; el mayor número de casos reportados se da en los varones, que tienden a utilizar métodos de suicidio más violentos. Se requiere conocer los factores de riesgo en las poblaciones vulnerables identificadas en este estudio.

Suicide is considered a public health problem. Suicidal behaviour, by definition, ranges from suicidal ideation to attempted or completed suicide. Over 800,000 people die by suicide each year worldwide, and in the United States about 45,000. However, these data may be underestimated, not only because of the social stigma attached to suicide and in some cases even the fact that it is illegal, but also due to omissions when determining the cause of death.1 In recent years, suicide rates have varied depending on the region and country reporting the data. In 2016, there was a burden of approximately 817,000 suicide deaths worldwide, corresponding to 1.49% of all deaths, and there was an increase from 1990 to 2016 of 6.7% in suicide deaths.2 In 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated that suicide cases would grow by 50% and reach 1.5 million deaths annually; this means that somebody commits suicide approximately every 40s.3 An increase in the suicide rate has also been identified among young people, to the point that they represent the highest risk group in a third of countries in the world.4

The approximate rate of deaths by suicide is estimated at 10.5/100,000 population, although there is a difference if the rates are separated by gender (16.3 males and 4.6 females per 100,000 population).5 This difference is also accentuated according to the victim's age, and more deaths are recorded among adolescents and young adults.6

There are multiple risk factors for suicide, with mental illness and substance abuse being the main factors. However, financial and relationship problems, recent crises and medical problems are all classified as potential factors associated with the personal context.7 There are special groups with higher suicide rates compared to the general population, which require greater attention, such as police officers, firefighters, prisoners, people who are hospitalised and homeless people.8

In Peru, mental health continues to be a public health problem, with high rates of mental illness. It is estimated that approximately 25% of the population in Peru suffers from depression, and 15% of this group is considered to be at risk of suicide.9 The suicide rates reported in the Hernández-Vásquez et al. study10 showed a significant increase, although there are variations between the years in which the study was carried out; the 2004 adjusted suicide rate was 0.46/100,000 population, while in 2013, it increased to 1.13. Suicide and depression tendencies may have increased in subsequent years, which reflects the need to study both areas in depth.

The objective of this research study is to determine the characteristics and distribution of suicide cases in Peru from 2017 to 2019 by gender and by region.

MethodsStudy designWe carried out a descriptive cross-sectional study based on a secondary analysis of the Sistema Informático Nacional de Defunciones (SINADEF) [National Information System on Deaths] provided by the Repositorio Único Nacional de Información en Salud (REUNIS) [Single National Repository of Health Information]. REUNIS is an information system for Peru which enables examination of data from different sectors (for example, social, economic and health), attached to which is SINADEF, the computer program for entering data on deceased people and generating death certificates and statistical reports, including foetal and unidentified deaths.

Participants and variablesThe database provides a section with cases of violent death since 2017, from which we were able to filter and identify suicide cases from three separate years (2017, 2018 and 2019). The variables extracted were age, gender, educational level, region of Peru, marital status, type of health insurance, post-mortem examination record, and method of suicide. Cases were excluded in which age or region data were not recorded or if the case was an individual born in Peru but who died in another country.

Statistical analysisThe STATA v16.0 program (Stata Corp., United States) conducted the descriptive statistical analysis. We used measures of central tendency and dispersion of the numerical variables and frequencies and percentages of the categorical variables. The variables included in the univariate analysis were sociodemographic characteristics and suicide characteristics (type and whether a post-mortem examination was performed). For the bivariate analysis, we used Student's t-test to evaluate the difference in ages between males and females and, for the association of qualitative variables, the χ2 test or, failing that, Fisher's exact test. To calculate suicide mortality rates by region, we used the standardisation recommended by the WHO,11 which adjusts by age group and using a coefficient; the results are expressed in number of cases/100,000 population. The population data were obtained from the same information system (REUNIS) and are projected from the measurements carried out by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (INEI Peru) [Peruvian National Institute of Statistics and Informatics]. To prepare the graphs and tables, we used the Excel 2016 program.

Ethical aspectsThis study was based on an analysis of a secondary database available for the general population (https://www.minsa.gob.pe/defunciones/); the data obtained were treated with confidentiality due to the coding maintained by SINADEF. As it was a study of secondary data, we did not require approval from an ethics committee.

ResultsFrom 2017 to 2019, 1679 suicides were registered in the SINADEF database. Cases in which the region was not registered (n=12) or the age (n=1) were withdrawn, resulting in a total of 1666 cases being included in the analysis.

Age-adjusted suicide rates in Peru were 1,44/100,000 population in 2017, 1.77 in 2018 and 1.95 in 2019. Comparing the three years analysed, the highest number of suicides was recorded in 2019, with a total of 636 (37.98%), with a predominance of males, at 434 cases (68.24%).

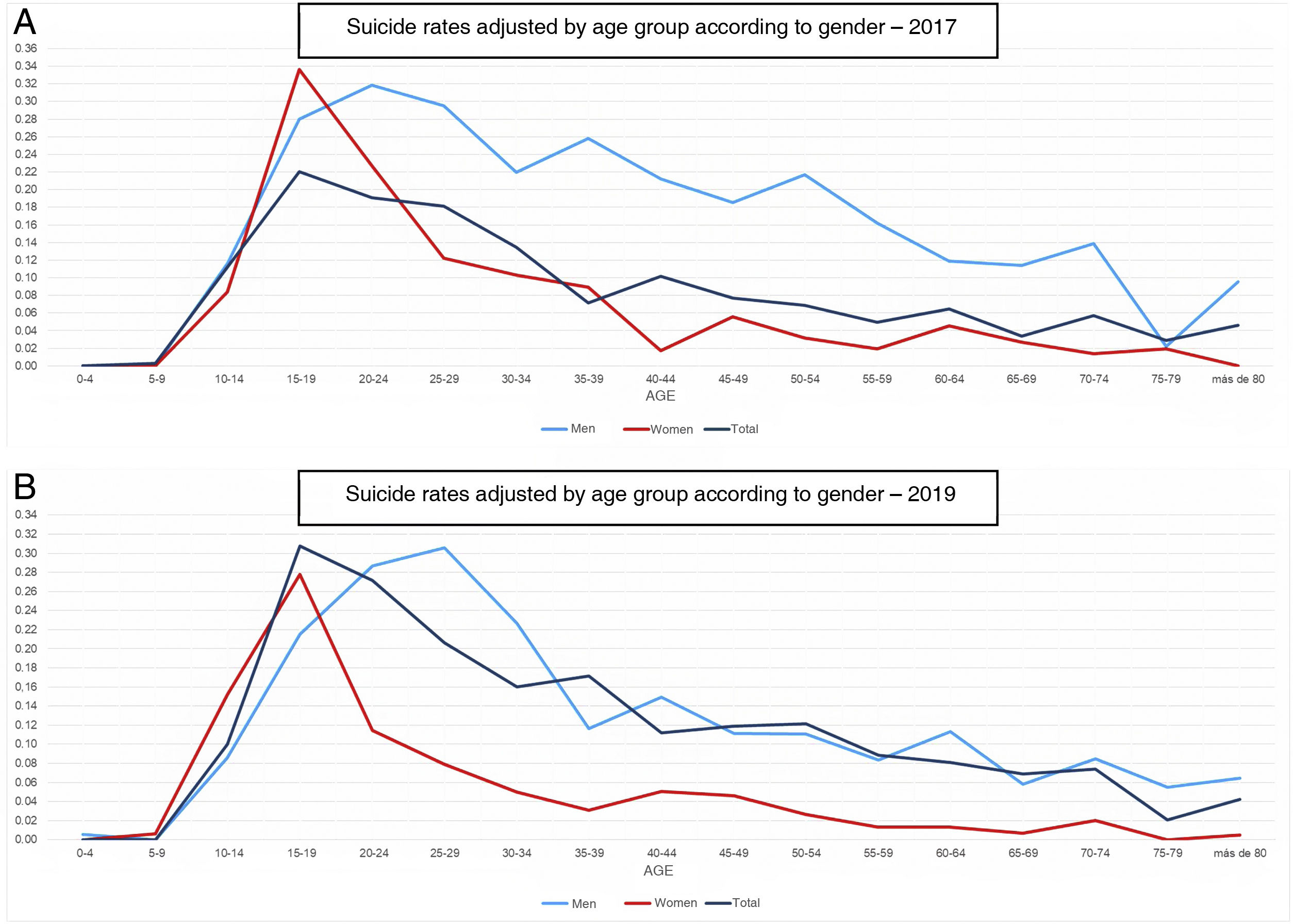

The mean age was 34.53±18.49 years. Of the total number of suicides recorded, 1155 (69.32%) were male. The mean age at suicide was higher among males than among females (37.49±18.96 vs 27.86±15.42; P<.001). Age-adjusted suicide rates were higher in males (2017, 2.07; 2019, 2.75) than in females (2017, 0.89; 2019, 1.19). The highest number of suicides was reported in the 20−29 year-old age group, with 463 cases (27.79%) (Fig. 1). In older adults (aged >59) there was a total of 219 cases (13.14%). In 371 cases (22.26%) they had completed secondary education, 1116 (66.99%) were single and 592 (35.53%) had access to healthcare through Seguro Integral de Salud (SIS) [comprehensive health insurance plan]. Of the total number of suicides registered, post-mortem examinations were performed on 1552 (93.08%) (Table 1).

General characteristics of suicides that occurred in Peru in the period 2017–2019.

| 2017 (n=460) | 2018 (n=570) | 2019 (n=636) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 34.19±18.86 | 33.68±18.33 | 35.56±18.34 |

| [0,1-4]Age groups | |||

| 5−9 years old | 1 (0.22) | 0 | 0 |

| 10−14 | 38 (8.26) | 43 (7.55) | 34 (5.35) |

| 15−19 | 75 (16.3) | 91 (15.96) | 105 (16.51) |

| 20−29 | 128 (27.83) | 169 (29.65) | 166 (26.1) |

| 30−44 | 99 (21.52) | 131 (22.98) | 147 (23.11) |

| 45−59 | 57 (12.39) | 62 (10.88) | 101 (15.88) |

| ≥60 | 62 (13.47) | 74 (12.98) | 83 (13.05) |

| [0,1-4] | |||

| [0,1-4]Gender | |||

| Male | 320 (69.57) | 401 (70.35) | 434 (68.24) |

| Female | 140 (30.43) | 169 (29.65) | 202 (31.76) |

| [0,1-4] | |||

| [0,1-4]Level of education | |||

| Unknown | 26 (5.65) | 60 (10.53) | 51 (8.02) |

| Illiterate | 10 (2.17) | 8 (1.40) | 8 (1.26) |

| Primary, not completed | 43 (9.35) | 72 (12.64) | 60 (9.43) |

| Primary, completed | 48 (10.43) | 66 (11.58) | 70 (11.01) |

| Secondary, not completed | 128 (27.83) | 138 (24.21) | 190 (29.87) |

| Secondary, completed | 106 (23.04) | 130 (22.81) | 135 (21.23) |

| Non-university higher, not completed | 23 (5.00) | 22 (3.86) | 26 (4.09) |

| Non-university higher, completed | 23 (5.00) | 20 (3.51) | 22 (3.46) |

| University higher, not completed | 15 (3.26) | 20 (3.51) | 27 (2.25) |

| University higher, completed | 38 (8.26) | 34 (5.96) | 47 (7.39) |

| [0,1-4] | |||

| [0.1-4]Marital status | |||

| Unknown | 2 (0.43) | 7 (1.23) | 7 (1.10) |

| Not recorded | 61 (13.26) | 68 (11.93) | 71 (11.16) |

| Single | 314 (68.26) | 359 (62.98) | 443 (69.65) |

| Married | 50 (10.87) | 70 (12.28) | 86 (13.52) |

| Widowed | 3 (0.65) | 8 (1.40) | 4 (0.63) |

| Divorced | 5 (1.09) | 5 (0.88) | 4 (0.63) |

| Separated | 2 (0.43) | 3 (0.53) | 3 (0.47) |

| Cohabiting | 23 (5.00) | 50 (8.77) | 18 (2.83) |

| [0,1-4] | |||

| [0,1-4]Type of health insurance | |||

| Unknown | 185 (40.22) | 303 (53.16) | 255 (10.09) |

| Comprehensive Health Insurance | 164 (35.65) | 174 (30.53) | 254 (39.94) |

| EsSalud | 55 (11.96) | 40 (7.02) | 72 (11.32) |

| Police/Armed forces | 11 (2.39) | 4 (0.71) | 6 (0.94) |

| Private | 6 (1.30) | 2 (0.35) | 8 (1.26) |

| Other | 39 (8.48) | 47 (8.24) | 41 (6.45) |

| [0,1-4] | |||

| [0,1-4]Post-mortem examination record | |||

| Performed | 427 (92.83) | 530 (92.98) | 595 (93.55) |

| Not performed | 17 (3.70) | 6 (1.05) | 41 (6.45) |

| Not recorded | 16 (3.48) | 34 (5.96) | 0 |

| [0,1-4] | |||

| [0,1-4]Suicide method | |||

| Hanging | 246 (53.48) | 333 (58.42) | 347 (54.56) |

| Firearm | 16 (3.48) | 13 (2.28) | 27 (4.25) |

| [0,1-4] | |||

| [0,1-4]Poisoning | |||

| Organophosphates, pesticides | 33 (7.17) | 38 (6.67) | 46 (7.23) |

| Other | 102 (22.17) | 112 (19.65) | 134 (21.06) |

| Other | 41 (8.91) | 34 (5.96) | 45 (7.08) |

| Not specified/not recorded | 22 (4.78) | 40 (7.02) | 37 (5.82) |

Values are expressed as n (%) or mean±standard deviation.

The most common method of suicide was hanging (926; 55.58%). Analysing differences between victims according to gender, hanging was the most prevalent method of suicide among males (58,87%) and females (48.14%), followed by poisoning (22.6% and 38.75%) and firearms (4.59% and 0.59%). These differences were significant (Table 2).

Bivariate analysis of the general characteristics and gender of the victims.

| Female, n (%) | Male, n (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| [0,1-4]Suicide method | |||

| Hanging | 246 (48.14) | 680 (58.87) | [2,0].001a |

| Firearm | 3 (0.59) | 53 (4.59) | |

| Poisoning | 203 (38.75) | 262 (22.60) | |

| [0,1-4] | |||

| [0.1-4]Marital status | |||

| With partner | 69 (13.50) | 228 (19.59) | [2,0].007a |

| No partner | 437 (85.52) | 916 (79.31) | |

| Unknown | 5 (0.98) | 11 (0.95) | |

| [0,1-4] | |||

| [0,1-4]Place | |||

| Home | 300 (58.71) | 746 (64.59) | [1,0].002b |

| Other | 211 (41.29) | 409 (35.41) | |

| [0,1-4] | |||

| [0,1-4]Level of education | |||

| No education | 104 (20.35) | 244 (21.13) | [3,0].116 |

| Primary | 187 (36.59) | 358 (31.00) | |

| Secondary | 186 (36.40) | 454 (39.31) | |

| Higher | 34 (6.65) | 99 (8.57) | |

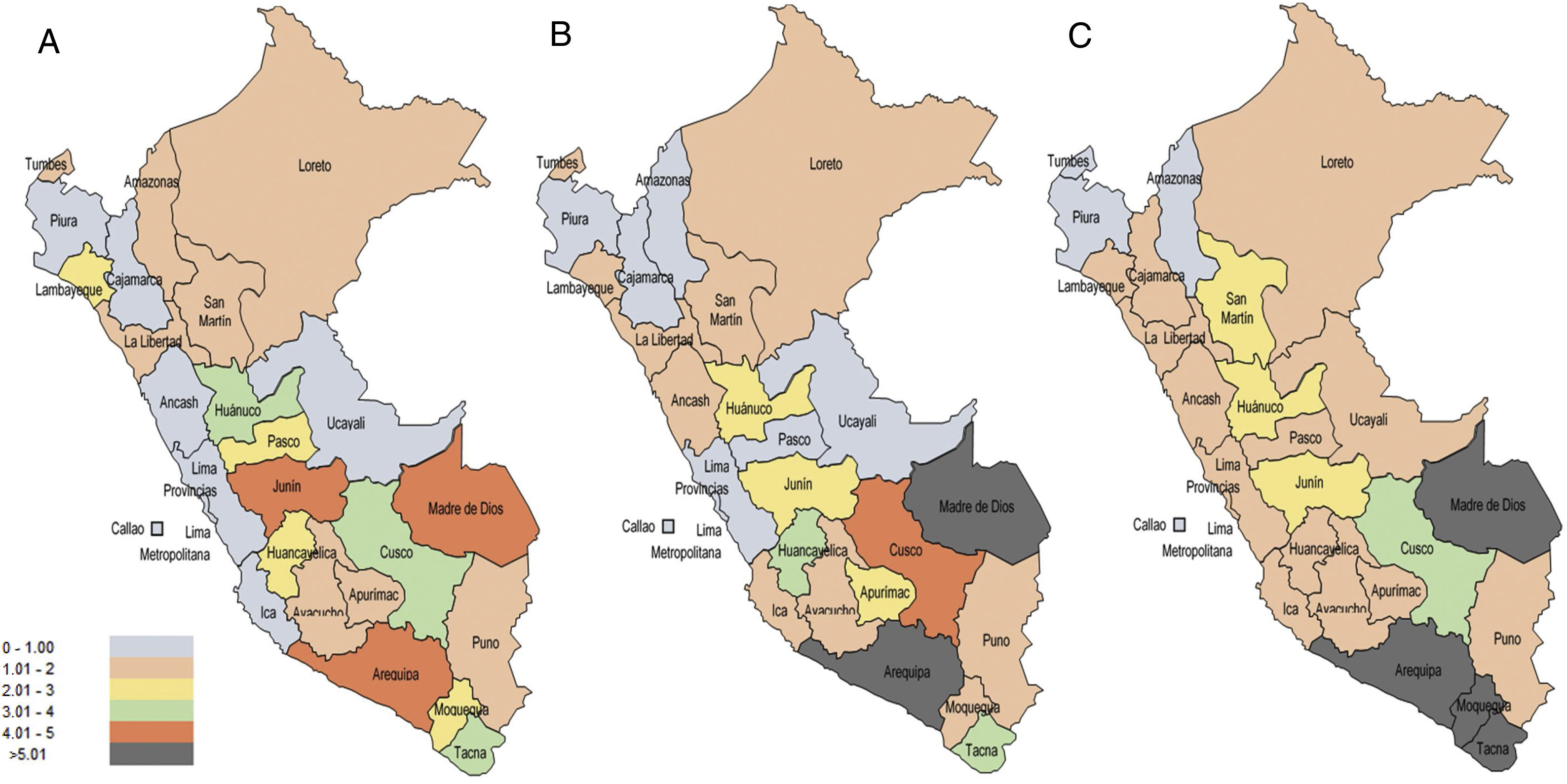

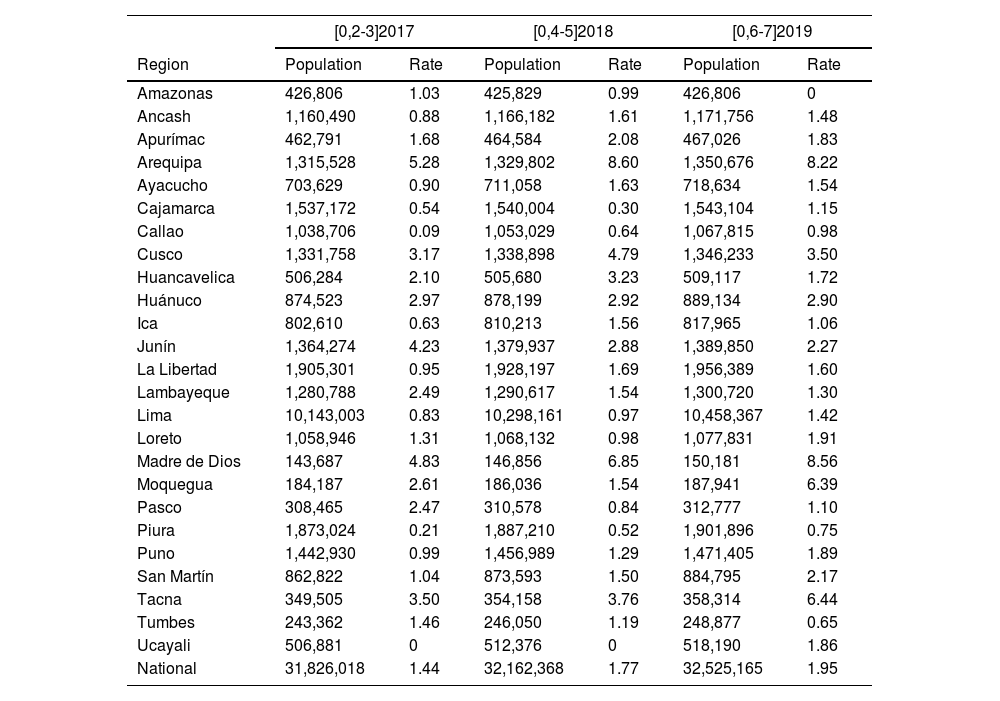

From the rates adjusted by regions and age groups, on average over the three years the regions with the lowest suicide rates per 100,000 population were Piura, the Constitutional region of Callao and Amazonas. The regions with the highest rates were Tacna, Madre de Dios and Arequipa (Fig. 2 and Table 3).

Suicide rate adjusted by age group according to region of Peru, 2017–2019.

| [0,2-3]2017 | [0,4-5]2018 | [0,6-7]2019 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Population | Rate | Population | Rate | Population | Rate |

| Amazonas | 426,806 | 1.03 | 425,829 | 0.99 | 426,806 | 0 |

| Ancash | 1,160,490 | 0.88 | 1,166,182 | 1.61 | 1,171,756 | 1.48 |

| Apurímac | 462,791 | 1.68 | 464,584 | 2.08 | 467,026 | 1.83 |

| Arequipa | 1,315,528 | 5.28 | 1,329,802 | 8.60 | 1,350,676 | 8.22 |

| Ayacucho | 703,629 | 0.90 | 711,058 | 1.63 | 718,634 | 1.54 |

| Cajamarca | 1,537,172 | 0.54 | 1,540,004 | 0.30 | 1,543,104 | 1.15 |

| Callao | 1,038,706 | 0.09 | 1,053,029 | 0.64 | 1,067,815 | 0.98 |

| Cusco | 1,331,758 | 3.17 | 1,338,898 | 4.79 | 1,346,233 | 3.50 |

| Huancavelica | 506,284 | 2.10 | 505,680 | 3.23 | 509,117 | 1.72 |

| Huánuco | 874,523 | 2.97 | 878,199 | 2.92 | 889,134 | 2.90 |

| Ica | 802,610 | 0.63 | 810,213 | 1.56 | 817,965 | 1.06 |

| Junín | 1,364,274 | 4.23 | 1,379,937 | 2.88 | 1,389,850 | 2.27 |

| La Libertad | 1,905,301 | 0.95 | 1,928,197 | 1.69 | 1,956,389 | 1.60 |

| Lambayeque | 1,280,788 | 2.49 | 1,290,617 | 1.54 | 1,300,720 | 1.30 |

| Lima | 10,143,003 | 0.83 | 10,298,161 | 0.97 | 10,458,367 | 1.42 |

| Loreto | 1,058,946 | 1.31 | 1,068,132 | 0.98 | 1,077,831 | 1.91 |

| Madre de Dios | 143,687 | 4.83 | 146,856 | 6.85 | 150,181 | 8.56 |

| Moquegua | 184,187 | 2.61 | 186,036 | 1.54 | 187,941 | 6.39 |

| Pasco | 308,465 | 2.47 | 310,578 | 0.84 | 312,777 | 1.10 |

| Piura | 1,873,024 | 0.21 | 1,887,210 | 0.52 | 1,901,896 | 0.75 |

| Puno | 1,442,930 | 0.99 | 1,456,989 | 1.29 | 1,471,405 | 1.89 |

| San Martín | 862,822 | 1.04 | 873,593 | 1.50 | 884,795 | 2.17 |

| Tacna | 349,505 | 3.50 | 354,158 | 3.76 | 358,314 | 6.44 |

| Tumbes | 243,362 | 1.46 | 246,050 | 1.19 | 248,877 | 0.65 |

| Ucayali | 506,881 | 0 | 512,376 | 0 | 518,190 | 1.86 |

| National | 31,826,018 | 1.44 | 32,162,368 | 1.77 | 32,525,165 | 1.95 |

Suicide cases reveal the state of mental health in different countries or regions. Individual study of each case is necessary if we are to be able to intervene appropriately and reduce numbers as far as possible. According to SINADEF, there was a total of 1666 suicide cases in Peru in the period 2017−2019. The suicide rates reported in this study are lower than those documented in other South American countries. The highest incidences of suicide are reported in Uruguay and Cuba (17–18/100,000 population) and the lowest, in Bolivia and Peru (2.3 and 1.9).12 Another study carried out in Peru reported suicide rates of 0.46 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.38−0.55) and 1.13 (95% CI, 1.01–1.25) for 2004 and 2013 respectively.10 Although suicide rates among Latin American countries are still lower than those reported in developed countries, recent trends show a strong growth pattern, especially among young males. In countries such as Chile and Brazil, an increase has been documented in the suicide rate in adolescents.13 Mexico has a documented trend towards an increase in suicides, one of the leading causes of death in young people in that country.14 In contrast, in Colombia, in 2000–2010, suicide rates tended to decrease, from 6 to 4.7 cases/100,000 population.15

The highest suicide rate was in the 20−29 year-old age group, in line with reports from around the world of the highest rates being registered in adolescents and young adults aged 15 to 29.4 This problem is associated in other studies to a lack of seeking therapeutic help by young adults.5 In the 5–14 year-old age group, although there was not a high rate of suicide cases, an exploratory analysis is required to determine the associated factors found in different studies, the most important of which being family problems.16 Suicide in children and adolescents should not be taken lightly. It is a serious health problem which affects all societies and cultures. No child or adolescent should consider suicide as a response to any emotional or situational problem. In Peru it has been reported that 16%–24.4% of adolescents have suicidal ideation, and 3% have attempted suicide at some point in their lives.17 There is less information, however, regarding completed suicide in children and adolescents here in Peru. As suicide in children and adolescents has a high prevalence and is becoming increasingly more frequent worldwide, we need to conduct more research in this area in Peru.

The suicide rate among older adults (age>59) found in this study (13.14%) represents a lower proportion than those found in other countries, such as the United States, Australia and Canada, where this age group represents over 18% of the total.18 Some associated factors in this population are social exclusion, loneliness, grief, chronic disease and physical pain.19,20

With regard to the level of education and marital status, we found a considerable difference in cases without completed higher education and being single, respectively. More than two-thirds of the individuals were single, in line with data worldwide, with several studies citing marriage as a protective factor.21 We also found that over 90% of the cases had not completed higher education, whereby, according to the evidence, it could be suggested that the rate of suicides is lower in people with higher education.19

Differences by genderIn cases of suicide, the male:female ratio was 2:1, in line with the epidemiological study in the WHO database.22 The global burden of disease study finds a higher rate for males aged over 20 in all registered regions and countries.3 Some researchers maintain that females attempt suicide earlier than males in developing psychiatric morbidity, which may represent less intent to die and more desire to communicate distress or change their social environment.23 Another theory related to gender roles mentions that males have a greater intent to die than females, who are reluctant to make serious suicide attempts because it is considered “masculine”.24

In terms of the suicide method, it is interesting to compare the results of our study with those of Hernández-Vásquez et al.,10 who found that in the period 2004–2013, the most common method of suicide in Peru was poisoning. However, they found that over the years the frequency of poisoning decreased, while suicides by hanging increased. This is in line with our study and with other research from around the world,25 in that the most used suicide method was hanging. We found that males used more violent methods for suicide (hanging and firearms), while females used less violent methods (poisoning). This difference is similar to that reported in other studies.23,24,26 A study conducted in Europe found that hanging was the most prevalent method of suicide among males (54.3%) and females (35.6%). In the case of males, other means were firearms (9.7%) and poisoning (8.6%), while in females, they were poisoning (24.7%) and jumping from height (14.5%).26 In all countries, males had a higher risk than females of using firearms and hanging and a lower risk of drug poisoning, asphyxiation and jumping from a height.26 Although females attempt suicide at a higher rate than males, as suicide attempts become more medically serious, the percentage of males involved in such attempts increases and gender differences decrease.27 Schrijvers et al.28 point out that the total duration of the suicide process is often shorter in males because it may only take them a very few suicide attempts to result in a completed suicide. It also needs to be taken into account that the methods applied to commit suicide not only depend on the availability and accessibility of the method, but also on the cultural, religious and social values in each region.28 Female suicide is culturally less accepted, so not all female suicides are recorded as such.27 Furthermore, it is possible that with poisoning, suicides are less obvious, unlike the more violent methods used by males, which can rarely be classified as accidental deaths.28

Differences by regionAnalysing the distribution by regions, there is a difference between the regions with a population of over a million; one limitation of the study is the lack of correlation between cities on the coast, the mountains and the jungle to develop predictive models by cities. By region, although the largest number of cases in absolute numbers was in the country's capital city (Lima), with 146 cases in 2019, by population rates this number loses significance when, as a result of the high population density, the rate is found to be 1–2 cases/100,000 population, because approximately one third of the country's population is concentrated in the city of Lima.

Implications for public health and decision makingThe results of this study show the need to create specific programmes for suicide prevention and surveillance of vulnerable populations and possible victims. The need to improve mental health in Peru in all areas led to the creation of Community Mental Health Centres, which provide care even at home to prevent fatal events.29 Based on the data revealed in this article, these centres need to be more widely distributed in order to improve care in the regions where the adjusted rates of death by suicide were found to have increased.29

Another strategy would be to distribute doctors and healthcare professionals who work in mental health (for example, psychiatrists, psychologists, therapists and social workers) to areas with the highest rates; there are reports that over 80% of psychiatrists are concentrated in the city of Lima.30 According to the WHO, suicide prevention and control measures include restriction of access to means of suicide, responsible media reporting, early identification and treatment, training of non-specialised healthcare personnel and appropriate follow-up of care.31

Strengths and limitationsOne strength of this study is that it includes all the cases registered as suicide in Peru. Additionally, information on the place where the death occurred is an extremely helpful tool for a reliable analysis of rates which can be extrapolated to each of the regions. By having specific rates by region, age and gender, care can be targeted at the population with the highest rates.

However, this study needs to be interpreted within its potential methodological limitations. Being descriptive, it does not show causal, risk or association relationships; this is one of the main limitations, besides the small number of variables found in SINADEF. For future studies, databases with more information are required to perform inferential analysis. Within the SINADEF data repository, forensic data and data recommended by experts should be considered in order to enable a better analysis and establish suicide risk factors in the Peruvian population. Furthermore, there is under-reporting of suicide cases, whether for cultural or religious reasons or due to problems with the registration procedure, and mortality rates may therefore be underestimated.

ConclusionsIn our analysis of the SINADEF database, we found that the suicide rate in Peru has increased in recent years. The young adult male population has the highest suicide rate in the country. There were more cases of suicide among single people and those without higher education. Males tend to use more violent suicide methods than females. The highest rates were identified in the regions of Arequipa, Moquegua and Tacna. National open data policies are required to continue research in this area and understand the factors related to suicide.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.